The Continental

|

|

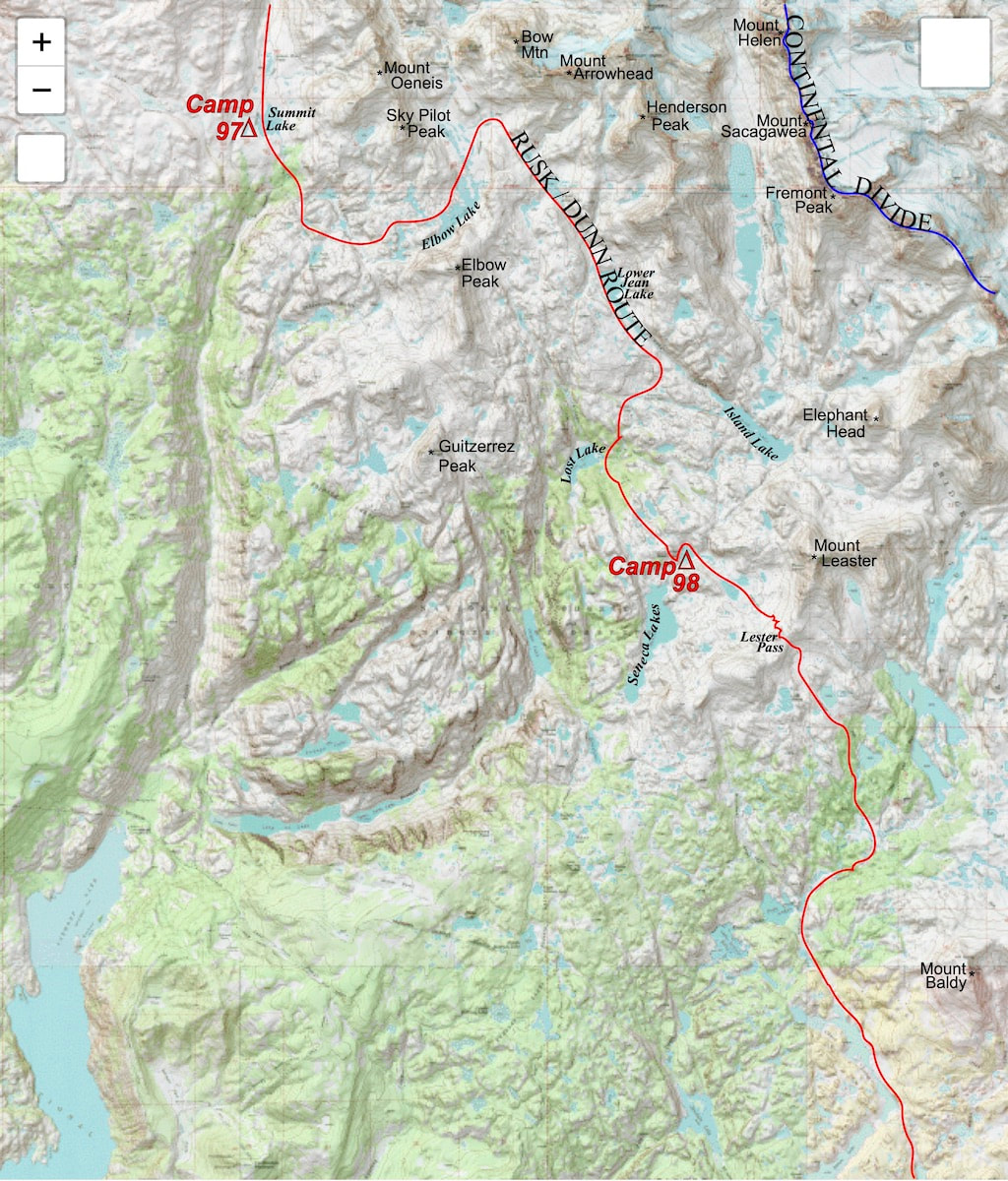

September 8th - 10th Wind Rivers, WY (Go to Pt 1) September 8 The night was dark and cold and somewhere in the pre-dawn hours it began to snow. When I awoke in the morning and heard nothing but silence I thought ‘Great, no wind!’ Then I looked out the tent door and saw four inches of snow on the ground and large flakes falling from the sky. I glanced over to where the trail had been but in the rocky tundra, four inches was all it took to completely erase its existence.

It was a good thing the terrain wasn’t difficult and the intended route of the trail easily defined by the landscape, because we were having one heck of a time trying to actually stay on the 3ft wide path, where the traction was best.

It had snowed on and off during the day and after the sun went down it was wintertime cold. We cooked supper in the vestibule of the tent and chit-chatted about the slick trail conditions but, more solemnly, wondered in low, barely audible tones if more snow would come in the night, like the weather was a terrorist about to take us hostage, which was pretty much true.

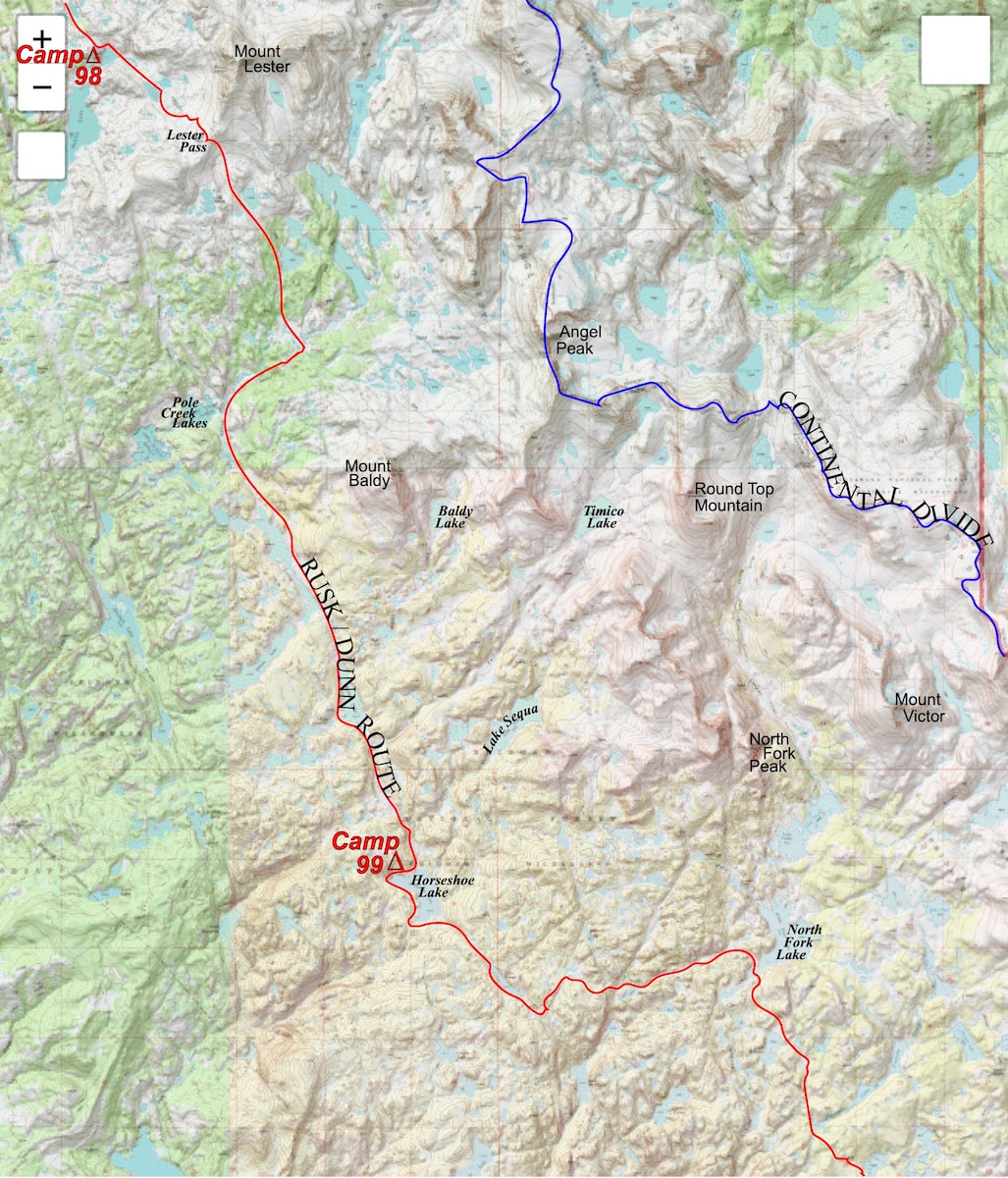

From Seneca Lakes we climbed up and over Lester Pass then made a long, gentle descent to Pole Creek, first through sparse trees then back down into the forest. At these lower elevations the snow dwindled and it became easier to make out the trail until we eventually found ourselves on the first stretch of easy hiking we’d seen since Yellowstone. Once down to Pole Creek Lakes I dropped my pack to wait for Craig.

Craig was still a ways back up the trail so I scouted out a good tent site then went back to get my pack just as he was arriving at the lake. He didn’t offer up any excuses or complaints when he arrived and we got busy with the camp set-up and supper going on the stove. We didn’t talk much, but then, being worn out will do that.

The topography was mostly lumpy, rocky and interesting to navigate, since the trail was faint and a little random in places. Craig and I ate lunch together and after that I saw very little of him until late in the afternoon.

Go to Part 52

0 Comments

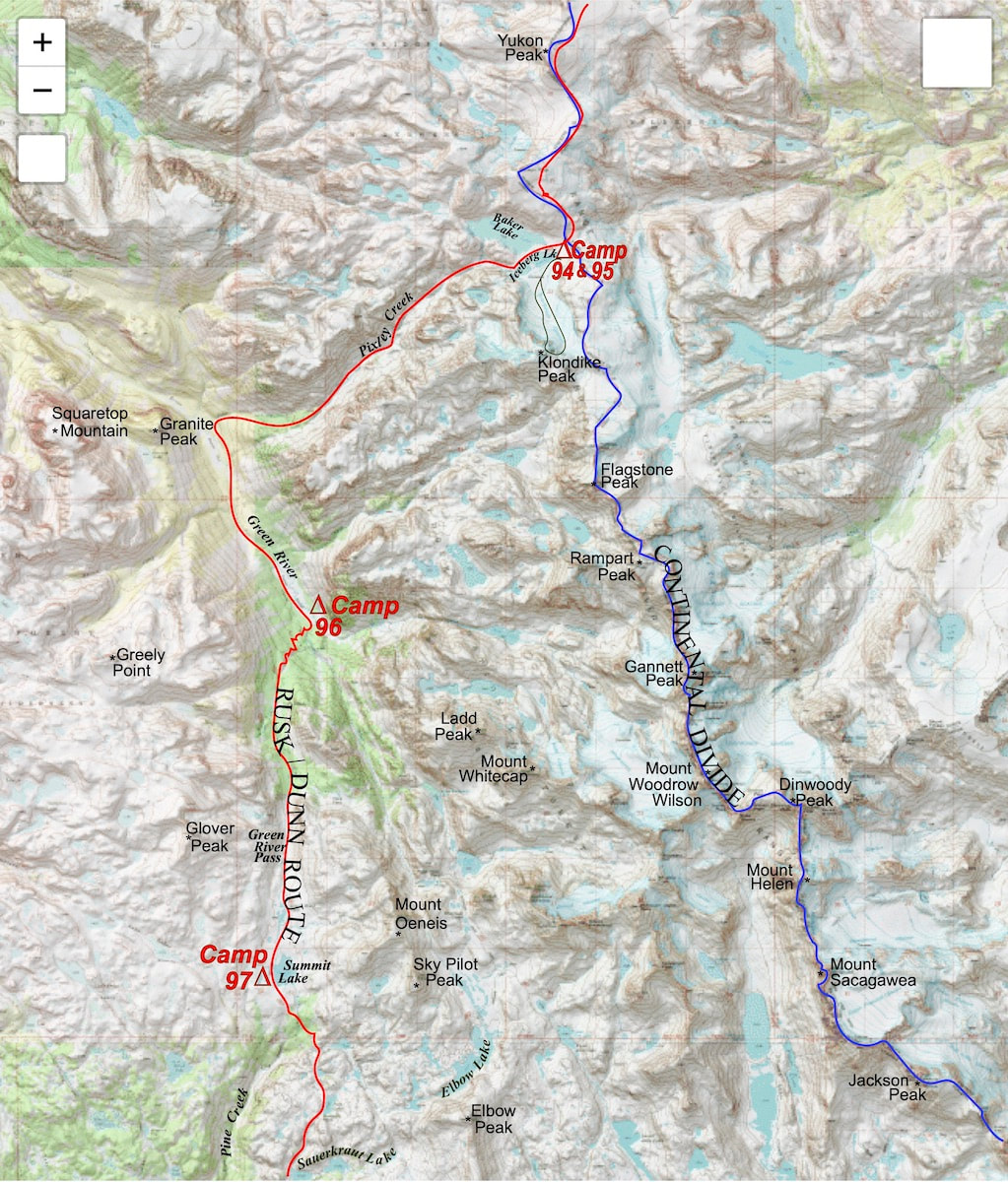

September 6th & 7th Wind Rivers, WY (Go to Pt 1) Now that we were in the narrow Pixley Creek Valley, there was practically no wind at all, although I could still hear it roaring overhead, and the clouds had opened-up to let the sun through; in other words, less than one mile from Iceberg Lake it was turning into a beautiful day.

I waited for a short bit down at the creek then, as Craig got close, I got-up and started-off again. There was no trail leading down Pixley Creek and the upper half of the valley was clogged with boulders; for Craig, these boulder descents were becoming a worst case scenario. It took quite a while to navigate our way down through the upper Pixley Creek valley to the steeply forested pitch below and my impatience with waiting for Craig to get down through the boulders was starting to grind over any empathy I had for his plight. Then, as we got closer to the valley floor, the descent turned steeper and cluttered-up with deadfall, causing more trouble that took up still more time. I didn’t violate our wilderness code to always stay within a holler or a visual of each other and I stayed within a visual of Craig as we descended but I didn’t wait for him to catch-up to me either, not until we reached the bottom of the valley and stepped out onto the Highline Trail, running along the Green River. Back in St. Louis we had foolishly dissed the Highline Trail as the ‘tourist’ route. Of course, this trail should have been our way through the Wind Rivers all along but, godamit, we were mountaineers, or at least we thought we were until we had to concede to this trail. Truth be told, the mountains were too complex for us to do what we were trying to do, which was to combine mountaineering with backpacking; we could either set-up a camp and go climbing or we could pack-up our gear and keep moving but trying to combine the two turned out to be fantastically difficult and logistically over our heads. Still, very little about stepping onto this trail felt right; It felt to me like cheating. Then there was Craig. 1,400 miles together and now he was struggling to keep up. If the problem was with his knees, which is what it looked like to me, then his trip was over, maybe not today but somewhere down the line it would become untenable. Craig finally joined me at the trail and, with little conversation beyond map pointing, we turned and started up toward the head of the valley. We made camp at Three Forks Park and the mood was dark, somber and quiet. I was still sulking over our abandonment of the ridgeline traverse, but as we set about putting our camp together, it was Craig I was fretting about. There was an elephant in camp that neither one of us wanted to talk about. While I had the urge to get this ‘knee thing’ and ‘lagging’ problem out in the open, given the growing magnitude of the situation, it was precisely the magnitude of the situation that made it so difficult for either one of us to get it out. If I brought it up, it would be to basically tell Craig, in so many words, that his trip was over - and I wasn’t about to do that. First off, I wasn’t completely certain the trip really was over for him. I mean, he wasn’t complaining about his knees or anything, but then again, he wouldn’t. I don’t know that Craig complained about anything, ever. I knew what I’d seen the past number of days, though, and ‘game over’ looked inevitable to me. But again, this was all still speculation, and I hadn’t even thought about what I would do if Craig did have to leave the trip. So, whatever was going to happen at this point was going to have to come from Craig because I really didn’t have a clear thought about what to say. For Craig, the anguish must have been even more acute. He and I had invested everything into this trip and beyond the Continental Divide, in our young lives, there was nothing else. Dropping out, because of injury or otherwise, would mean ‘quitting’ with the added burden of abandoning me alone in the wilderness, and that was something Craig was not prepared to do. As long as he could still manage his load and get to the next camp then that’s what he intended to do. Besides, he honestly figured he was getting along well enough; up-hills and rolling terrain seemed okay and now that we were back on a trail, things were bound to improve. By morning, the elephant had grown a bit larger. September 7 The Green River Valley next morning was sunny and windless, with crisp, autumn temperatures, a deep-blue sky and colorful, underbrush foliage. The morning started like any other, except a schism, a shift, a change between Craig and I had occurred that made this morning different. There was a cloud of despondency hanging over us both and I felt no enthusiasm toward the day.

As we were plodding up the trail, I’d kept rolling over scenarios in my head on how Craig could continue with the trip but the only conclusion I could come to was that he was probably going to have to drop-out. There weren’t enough rest days on the calendar for him to revive rickety knees. Then I’d mull over what was I going to do if Craig did have to drop out – go on alone? Through Colorado, late in the season? By myself? Or just call a halt to the whole thing and, if nothing else, at least take a break? Then the dark clouds swirling around me would switch over to the ridgeline traverse failure, letting that disappointment further pound away in my head, inevitably leading to anger at all of this fucking climbing equipment we continued to haul around, completely worthless to us now. Meanwhile, Craig, although a bit slower than normal, had made the climb up out of the valley with little trouble and was showing no signs of distress. But then, uphill wasn’t the problem, it was the going back down. But hell, I didn’t know, maybe now that we were back on a trail his knees wouldn’t get jolted so bad. Just beyond, on the other side of the pass, was Summit Lake, an alpine jewel set into the tundra and a perfect place to camp, so when we got there we dumped our packs and called it quits. It was cold and windy as we cooked-up supper but the sun broke through the clouds just before dropping off into the horizon, creating a dramatic sunset across the lake for the brief moments it lasted. September 8 The night was dark and cold and somewhere in the pre-dawn hours it began to snow. When I awoke in the morning and heard nothing but silence I thought ‘Great, no wind!’ Then I looked out the tent door and saw four inches of snow on the ground and large flakes falling from the sky. I glanced over to where the trail had been but in the rocky tundra, four inches was all it took to completely erase its existence. Go to Part 51

September 5th & 6th Wind Rivers, WY (Go to Pt 1) Holyshit was right, we were incredibly exposed at the top of the couloir, and with metal crampons strapped to our feet, metal ice axes in hand and metal climbing gear slung around our necks, we were nothing more than mobile lightning-rods.

protection; if one of us did happen to slip and fall in the panic of the moment, being roped together with no protection meant we were both going to get plucked off the mountain. But that didn’t seem to matter at the moment.

By now, lightning was striking the summit of Klondike, not even 300 yards from where we sat crouched under the rocks, and the noise from the thunder was deafening. Seconds turned to minutes as I unknowingly clung to Craig’s arm, in a ‘take-cover’ kind of way, and wished with all my wishing power for the whole thing to just blow over, real quick-like. Each flash followed by an instantaneous crash was a huge jolt to the system, felt deep inside the body, and with the radio wave sound of electricity in the air the lightning seemed to be honing-in on the rock outcrop sheltering us. I looked at Craig who looked straight back at me with terror in his eyes, which had to be identical to mine since I thought for sure we were about to get fried. It took about 10 minutes for the deadly part to pass and it was, by far, the longest 10 minutes of the day. Of course, once everything was cool with the world again, it was back to black humor but also mixed with the terror-aftershock of what had just happened and knowing we were walking away from it by sheer luck of the draw.

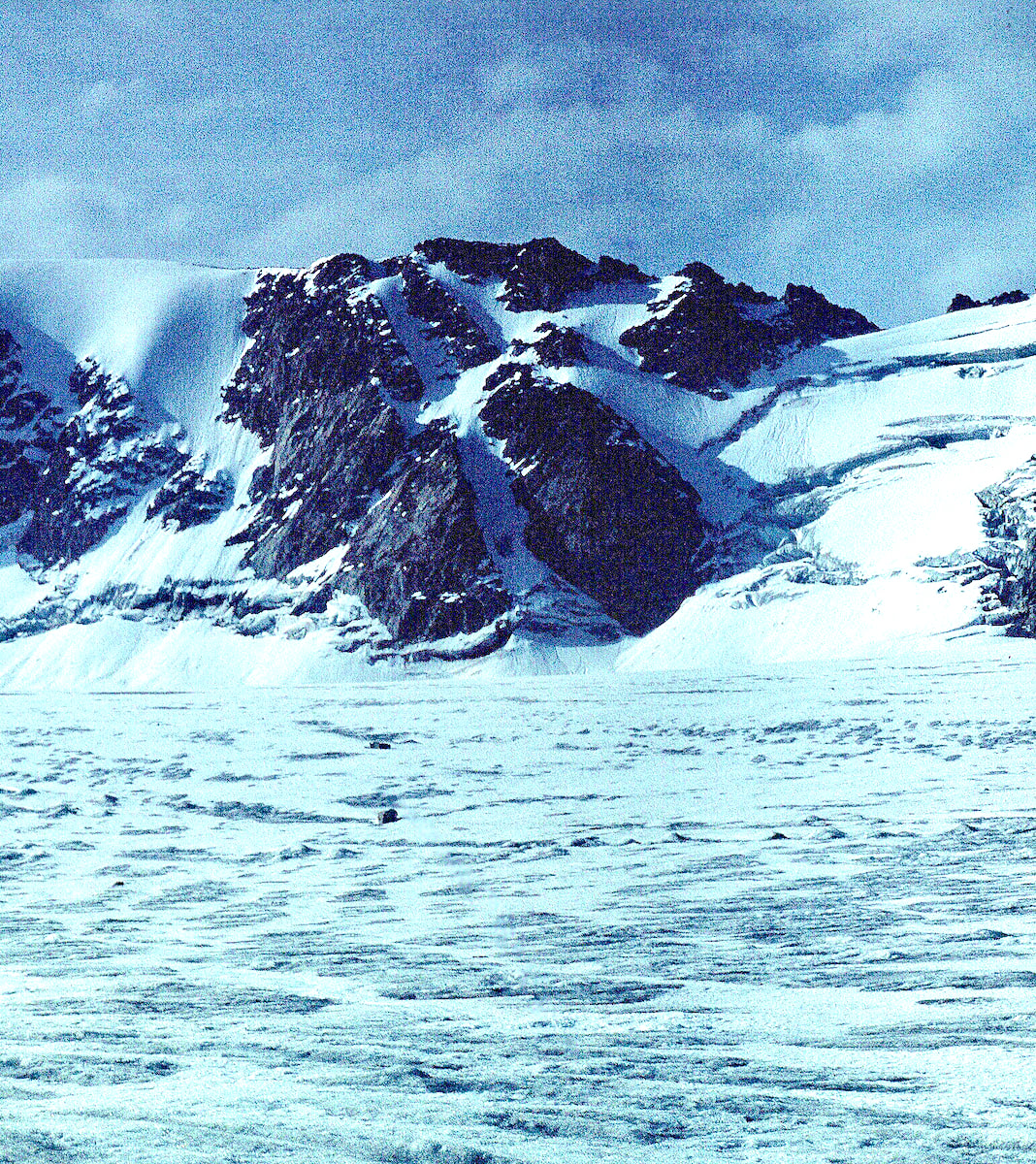

September 6 Around dawn the next morning the wind picked-up to a ferocious speed, keeping Craig and I tent-bound for hours and eventually shouting back and forth about what to do. The wind was too high to consider pushing further out on the Divide but the wind was also so sustained that I began to fear staying put would eventually end-up shredding the tent.

Our position at Iceberg Lake was horrendous, the lake sat just a few hundred vertical feet below a narrow pass formed by Yukon Peak, directly to the north, and Klondike Peak to the immediate south. These two massive mountains served to funnel the jetstream winds through the narrow pass like a firehose and our closest escape from this mayhem was a small canyon just off the southwest end of Iceberg Lake. The gale was blowing out of the northwest, so pretty much right in our faces as we fought our way around the north side of Iceberg Lake then doubled back south between Iceberg Lake and Baker Lake to reach the steep, narrow gully below the lakes. We descended into the gorge until we got low enough for the canyon walls to provide a substantial wind break and dropped our packs. Now what? We were in a vice; we could stay put and try to wait out the jetstream winds then go back up, or we could go down into the valley and resume our trek south on the Highline Trail. We dithered over the maps, we sat and stared out into space, time passed.

I was getting more despondent as the time passed; I didn’t want to give-up on the ridgeline traverse. Shit, we were finally into it, our packs were light enough and we’d even done a practice climb on our rest day, godamit, we were ready for this! But we didn’t have the supplies to wait around, either, and the jetstream winds could be scouring the peaks for days. Who knew? So that was it, we turned and began our descent. The sense of failure I felt at turning away from the peaks was crushing, this was the final blow to our notion of tracking the Continental Divide across its most difficult sections. “The strictest line possible” philosophy was dead. We had overestimated what we could do and underestimated the many variable conditions we needed in our favor to climb through the high peaks.

Although logic had dictated, I hated the decision we’d just made, and now I sat watching Craig make his way down through the boulders on shaky legs. Go to Part 50

rocky terrain to start until we were able to find linking stretches of tundra between the rocks and boulders.

on the ground; up and through more steep, boulders leading along the ridge to the peak.

It took us a couple of hours to climb the north ridge and traverse over to the south side. By the time we reached the descent, we were both fatigued and, while trying to put a mask over it, Craig looked pained.

Descending through these boulders was like coming down a jumbled-up set of stairs with the treads anywhere from two to four feet apart, sloped and cocked at all kinds of crazy angles, causing an awkward jolt to the legs and joints with each step. As I watched Craig descend the boulderfield, working hard to catch-up to me, he certainly looked wobbly and his knee joints, even from a distance, looked like they were about to dislocate at times. section of boulders then managed to find some swaths of tundra that helped get us the rest of the way to the lake.

The late afternoon sun was warm and the wind had mostly died out to where it was pleasant to sit on the rocks by the lake, and that’s just what we did, in awe of the scenery for quite some time before finally scouting out a tent site.

After that whole project was done, we set-up the cook gear and started water for soup, munching on lunch food that we hadn’t got around to eating while up in Yukon’s boulderfields. The tinned chicken with instant rice, smothered in lots of margarine and seasoned salt, tasted almost gourmet in this setting. Then, while brewing hot drinks after supper, we watched the clouds behind Klondike Peak turn a brilliant, glowing orange as the sun slowly melted away, making for a cinematic sunset. After which, and with no delay, the temperature turned frigid and we retreated to our warm, down sleeping bags to read and write. September 5 Per our planning from a year ago, today was a scheduled rest day, and boy, did we pick a gem of a place for that! I slept like the rocks I was sleeping on and in the morning I awoke to pristine silence. Not a sound, no wind, and a glance out the tent window revealed a deep, blue sky. ‘Yes!!’ I rolled over and went back to sleep. We dozed until the sun had warmed the inside of the tent to a comfortable, t-shirt temperature then put on our warm clothes and ventured out into the sparkling, crystalline morning. We were carrying dried pancake mix and brown sugar for rest days, so we proceeded to fix and feed on pancakes topped with squeezed margarine and brown sugar until our stomachs demanded a stop to that shit.

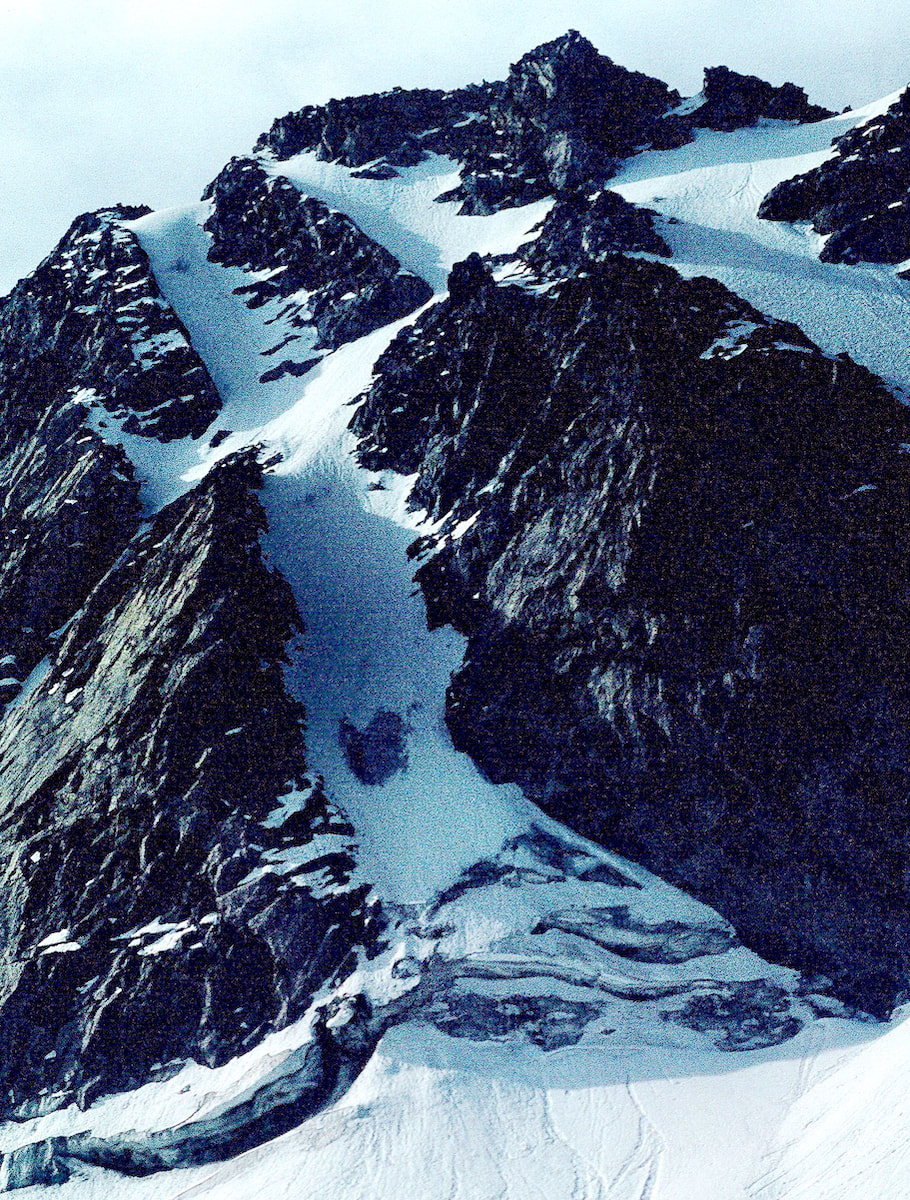

couloir running straight from the glacier to the summit, and it was just begging for someone to come over there and climb it.

Craig hadn’t considered going for a climb until I mentioned it, and then it must have gotten him to thinking because about ten minutes later he said “Okay, sure, let’s go climb that couloir”, suddenly stoked to go adventuring.

In the narrow crevice of the couloir we had been unable to see the storm bearing down on us from the west and that crack of lightning alerted us to dark, threatening clouds moving-in overhead. Then another blinding flash, followed so closely by thunder that the lightening had to be almost on top of us, put us into panic mode. Holyshit was right, we were incredibly exposed at the top of the couloir, and with metal crampons strapped to our feet, metal ice axes in hand and metal climbing gear slung around our necks, we were suddenly nothing more than mobile lightning-rods. Over the top and, hopefully, down to some sort of rock shelter on the other side was our best shot at ‘safety’, putting us in a race to the summit against a lightning storm. Go to Part 49

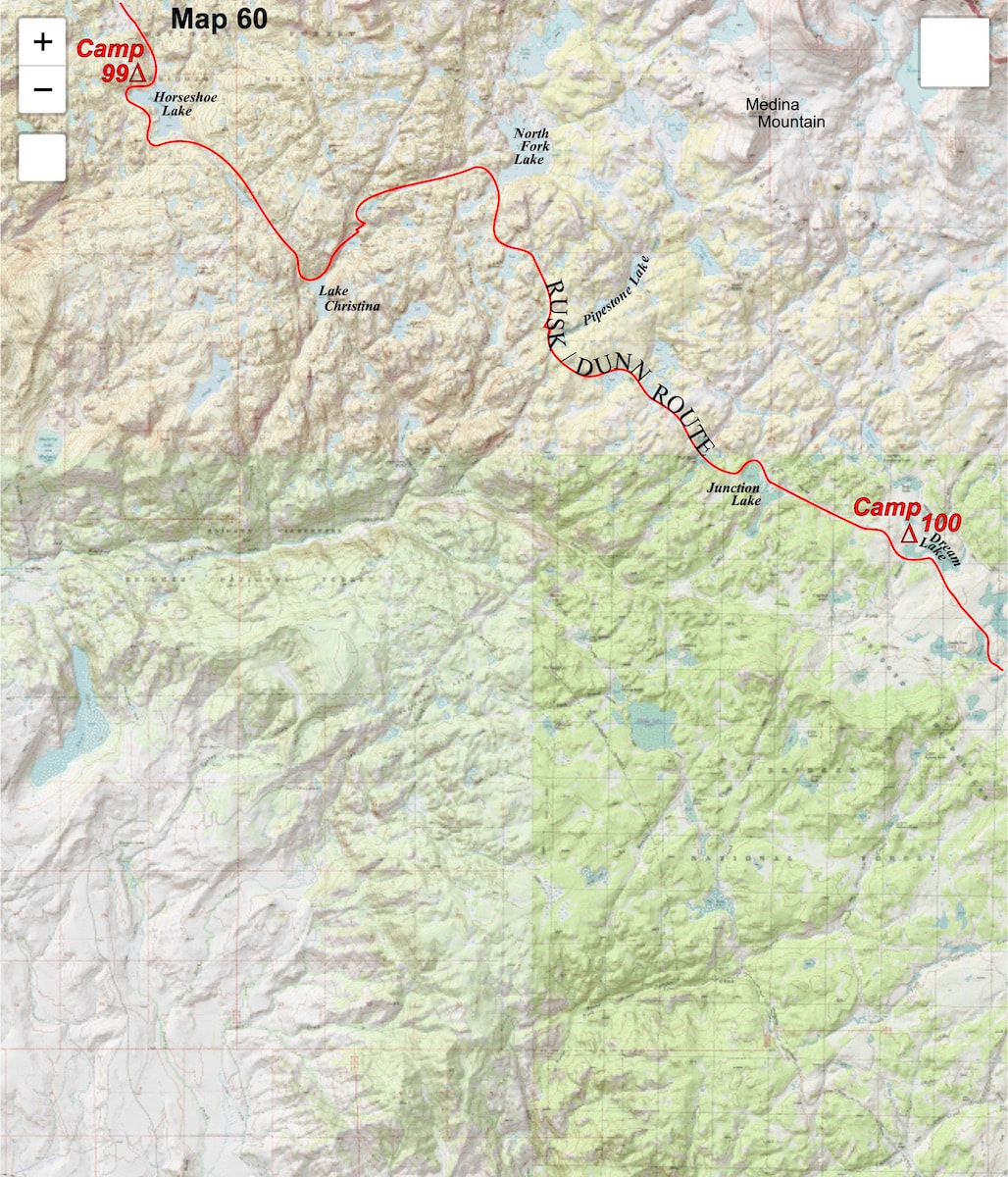

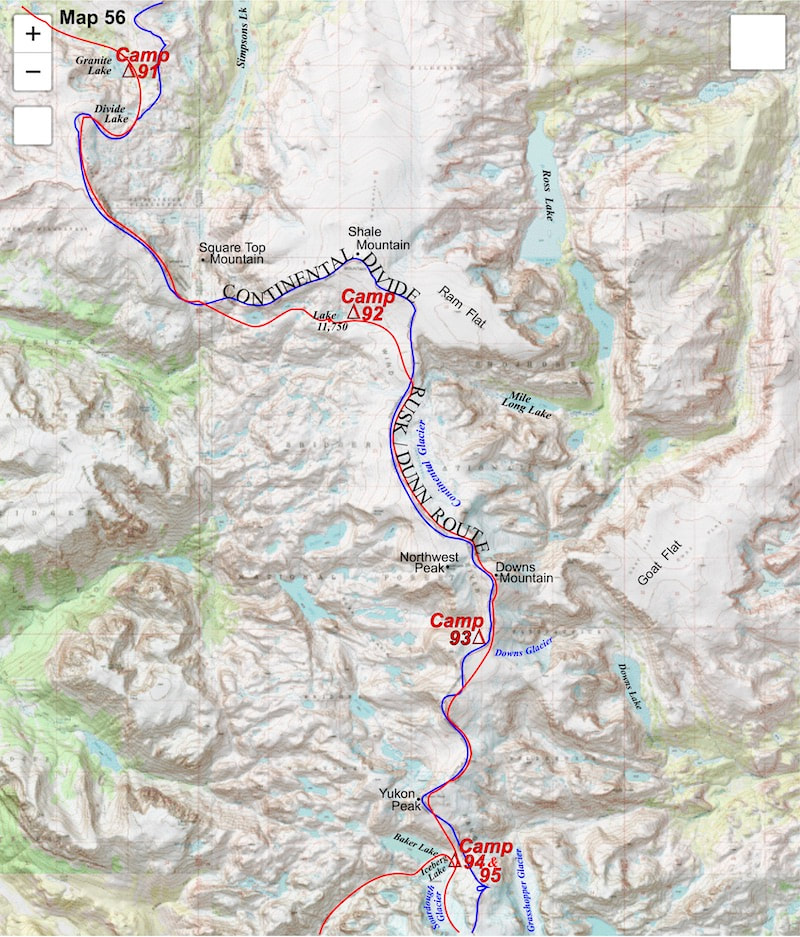

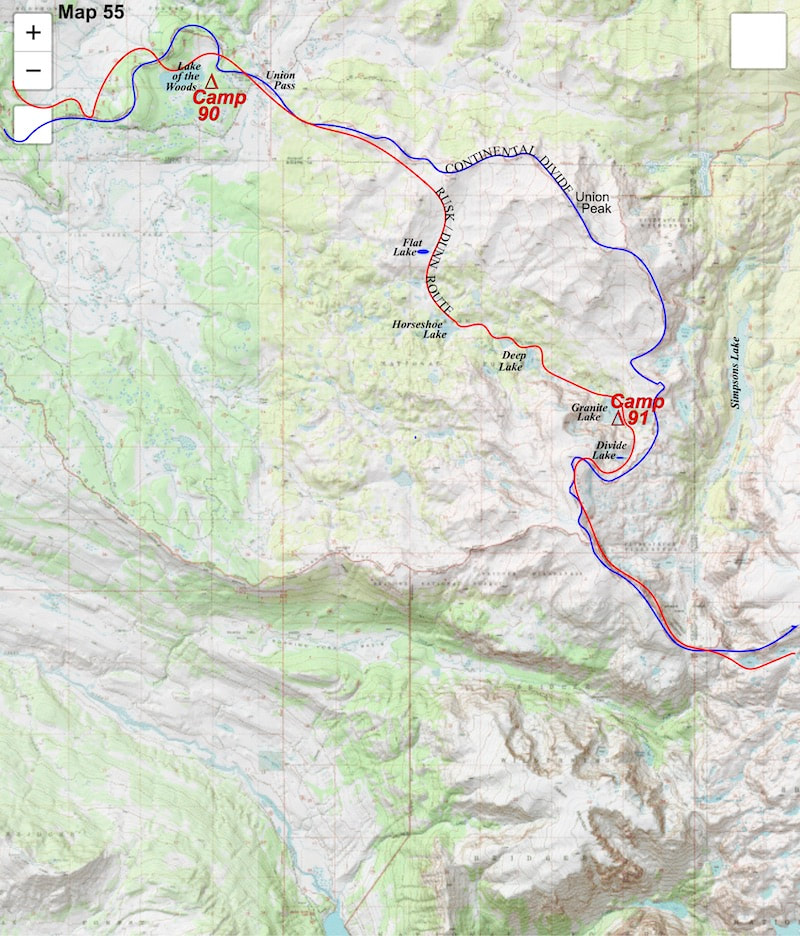

Our day started with an easy hike down to Union Pass then a short bushwhack to find a two-track leading up Union Peak. I was finally getting my pack adjusted and riding better but the 1,000 foot elevation gain up the ridge reminded me that the packs were still too heavy. At a saddle below the top of Union Peak we descend through open tundra down to Flat Lake then continued a ways further down to Horseshoe Lake. At Horseshoe Lake we were surprised to see a tent and then a couple fishing along the lakeshore, who turned out to be newlyweds on their honeymoon. I figured either the chick really loved fly fishing or the dude had no money for a honeymoon but either way they were chatty and happy and Craig and I welcomed the excuse to drop our packs and listen to them yak for a while.

Then I flashed back to Lava Mountain; that was the last time we had descended anything of significance, and there, too, Craig had struggled to get down. So… what was the deal, was Craig handicapped in some way? I didn’t even want to think about the implications of that, and maybe I was making something out of nothing, so I chose to ignore it. September 2 The next morning was sunny on the east side of the Divide but we were on the shady side with a biting wind that made packing our gear nippy cold; I’d sort of forgotten what it was like to stand around freezing my ass off while trying to warm-up numb fingertips. We had been traveling off trail since Union Peak and Granite Lake definitively marked the end of casual, cross-country hiking; it was going to be all rock and boulders from here. As we worked our way up the steep, boulder impacted slope above Granite Lake, we got into a wind break where it was calm, warm and sunny but climbing through the steep boulderfield was tedious work and took a lot of energy. Then, as we slowly rolled over the top of the boulder slope to Divide Lake, the wind returned with rising, constant harassment.

The wind had been blowing steadily since topping-out over the boulderfield at Divide Lake, but as we crested over the top of the ridge on Three Rivers Mountain from the east, we got blasted by a gale of wind out of the west that had us staggering to stay upright. The roar of the wind made communication impossible but there was little to discuss anyway since, from here, there wasn’t much choice but to turn south along the ridge and begin climbing our way up through more boulders to the summit, only now with powerful gusts of wind shoving us around and threatening us with a body-slam into the rocks. At the top of Three Rivers Mountain the boulders gave way to stretches of tundra, making our progress easier as we traversed the 3 miles of ridgeline, but the wind continued to howl, hammering us for hours, until the noise and constant shoving became unnerving. Late in the afternoon, as we were traversing the last mile of ridgeline, the wind finally laid down, which came as a great relief to my rattled nerves, and by the time we reached our remote camp at Lake 11,750 is was dead calm.

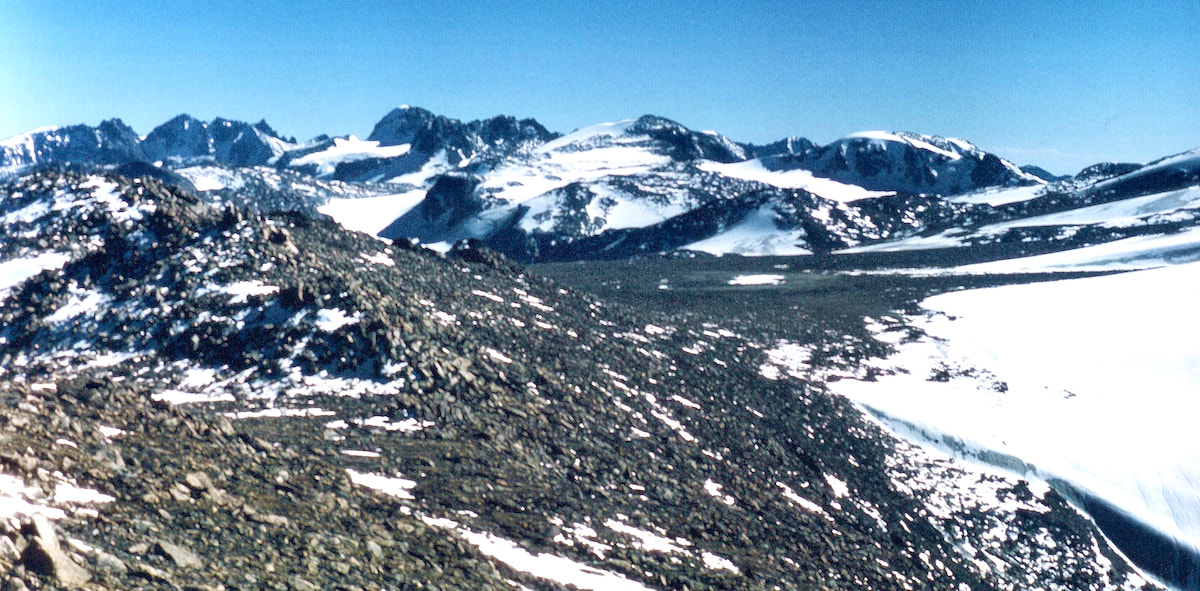

September 3 After the sun disappeared, the temperature dropped like a stone and in the morning there was solid ice in the cookpot we had filled the night before. Our camp was shaded by the ridge of the Continental Divide, blocking out the warm, morning sun and making for another cold start, but it was a small price to pay for yesterday’s basking afternoon and stellar sunset. From our camp at the lake, we climbed for over a mile across rocky terrain to reach the Continental Glacier at 12,000ft. At the glacier we stopped to don our crampons and eat granola bars before continuing another two miles up the glacier to the north rib of Downs Mountain at 13,000ft. By the time we reached the backside of Downs Mountain I was tired and the wind was starting to come back into play with gusts that were suddenly knocking us around. We left the crisp, frozen neve of the glacier, repacked our crampons and started the arduous boulder climb up the north side of Downs Mountain. When we finally crested over the top of Downs Mountain at 13,200ft, the view looking south into the heart of the range was staggering, both in its grandeur and daunting terrain. However, the icy wind ripping over the top made stopping to admire the view impossible and we moved quickly across the summit to the steep, southside descent, which was another difficult mile of boulder navigation with the wind again trying to topple us over. Craig fell further and further behind on the descent and I briefly waited a couple of times but the winds were too cold for waiting long and I came out onto the rocky plateau above Downs Glacier well ahead of him. On the plateau I scouted for a spot to set our camp that would be wind protected and, hopefully, on tundra but by the time Craig had reached me I had found neither. Together, we dashed about the plateau looking for something, anything, that would offer us a measure of protection from the wind but there wasn’t a wind block to be found. In addition, there wasn't a decent patch of tundra to be found either, so this meant we were going to have to set-up our 17-stake tent on rocky rocks in 40mph winds. We ended up using stakes, rocks and guy-line in a variety of creative ways to get the tent erected and braced against the wind, but it didn’t happen quickly. Finally inside the tent and out of the wind, we set about getting the stove lit in the cramped quarters while the wind battered our tent with the machinegun rat-tat-tat of snapping nylon, drowning out any shot at conversation. It was going to be a rough night. September 4 The wind calmed down sometime during the dark hours and I was able to get some sleep but by morning it was back again, racing across the plateau. Temperatures were below freezing and with the wind I didn’t even want to get out of the tent to take a leak, let alone try and pack-up and move camp.

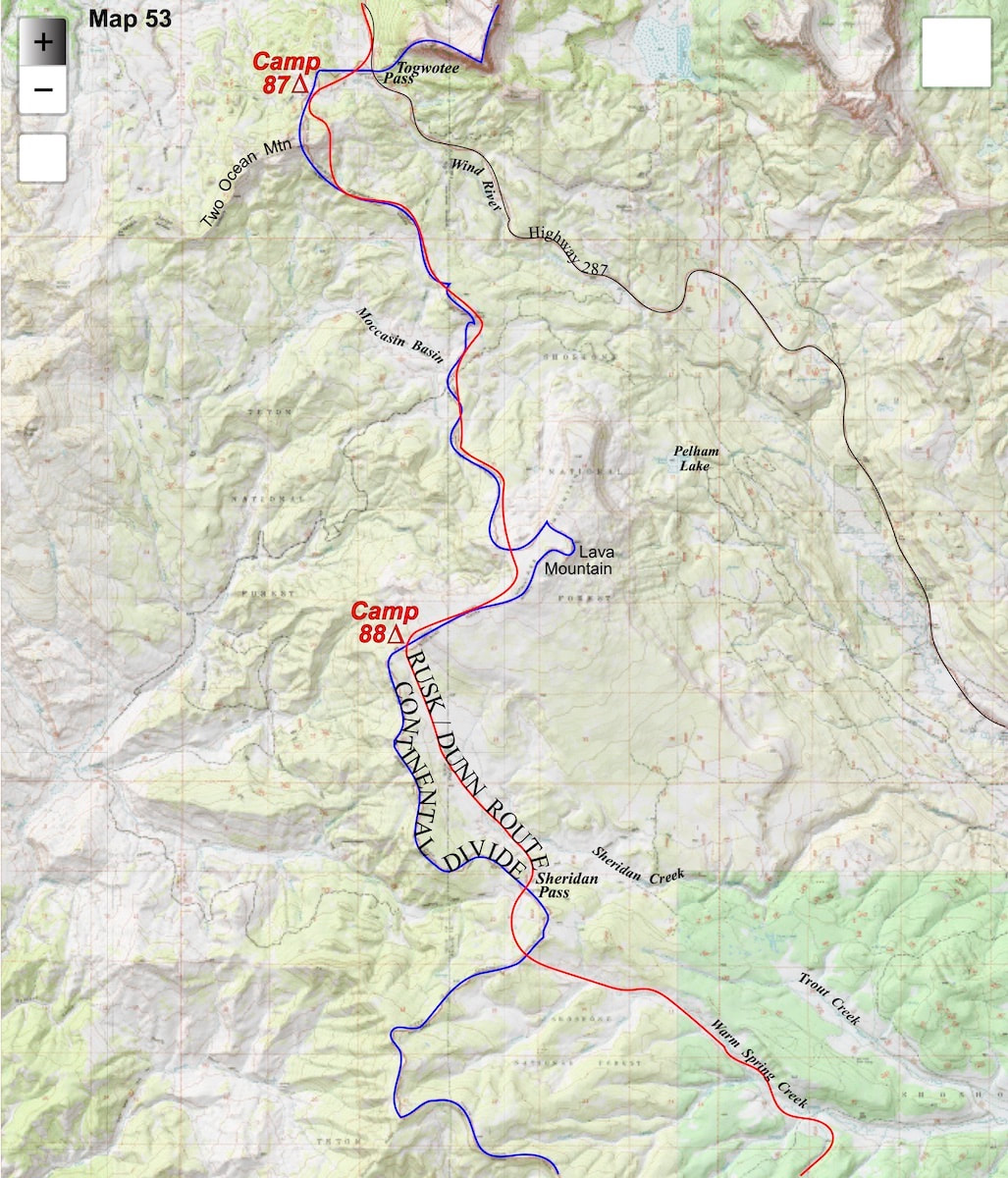

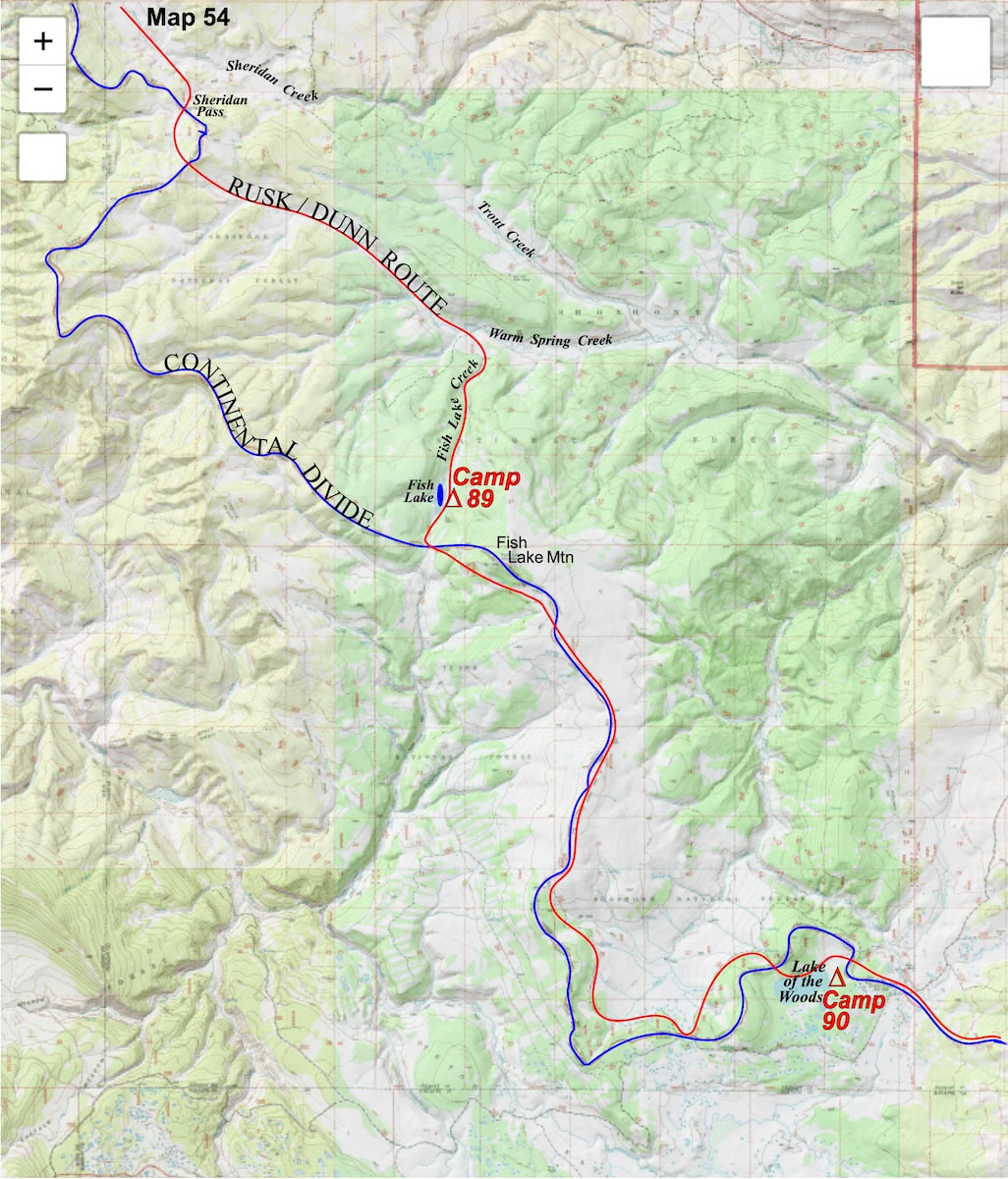

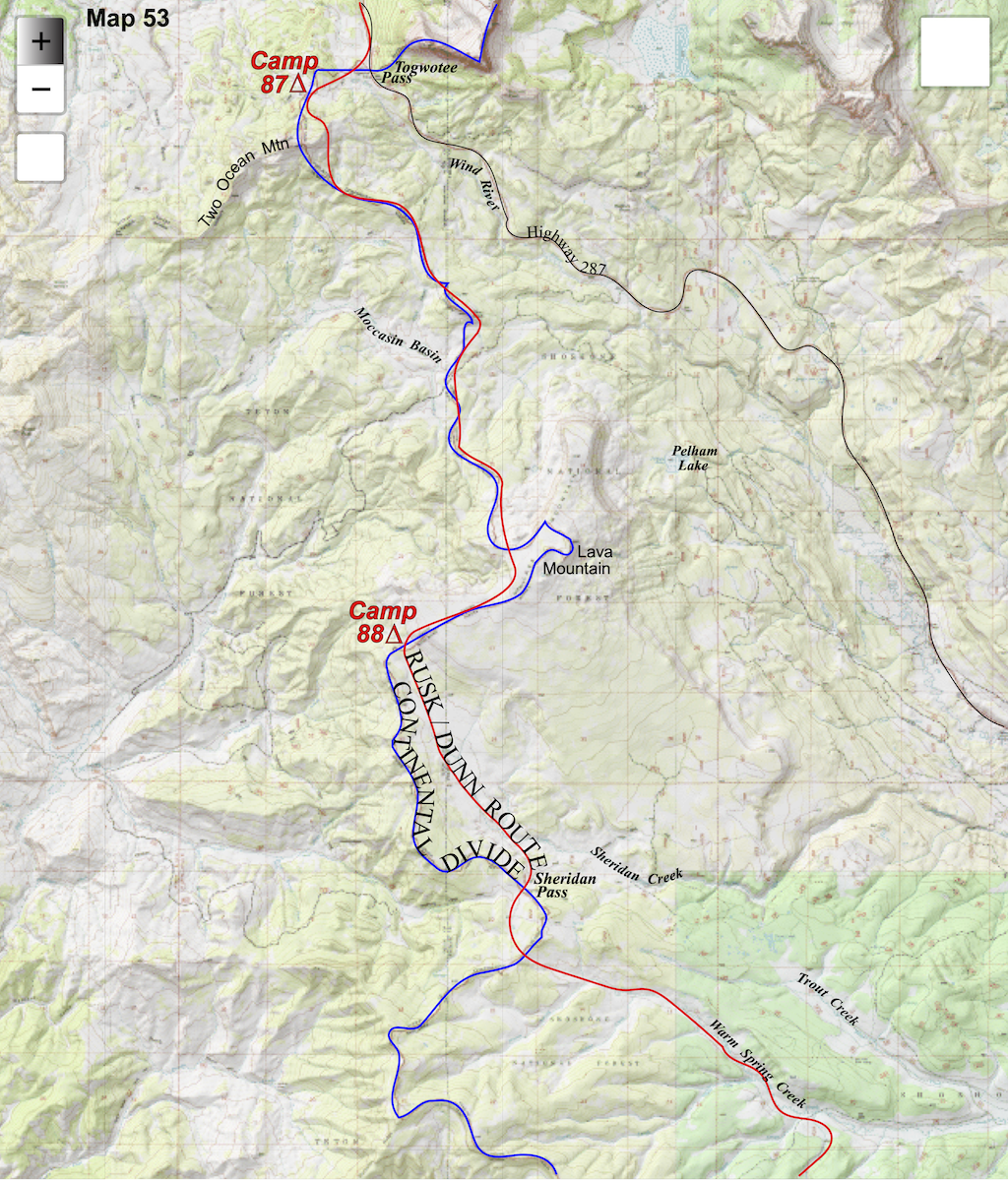

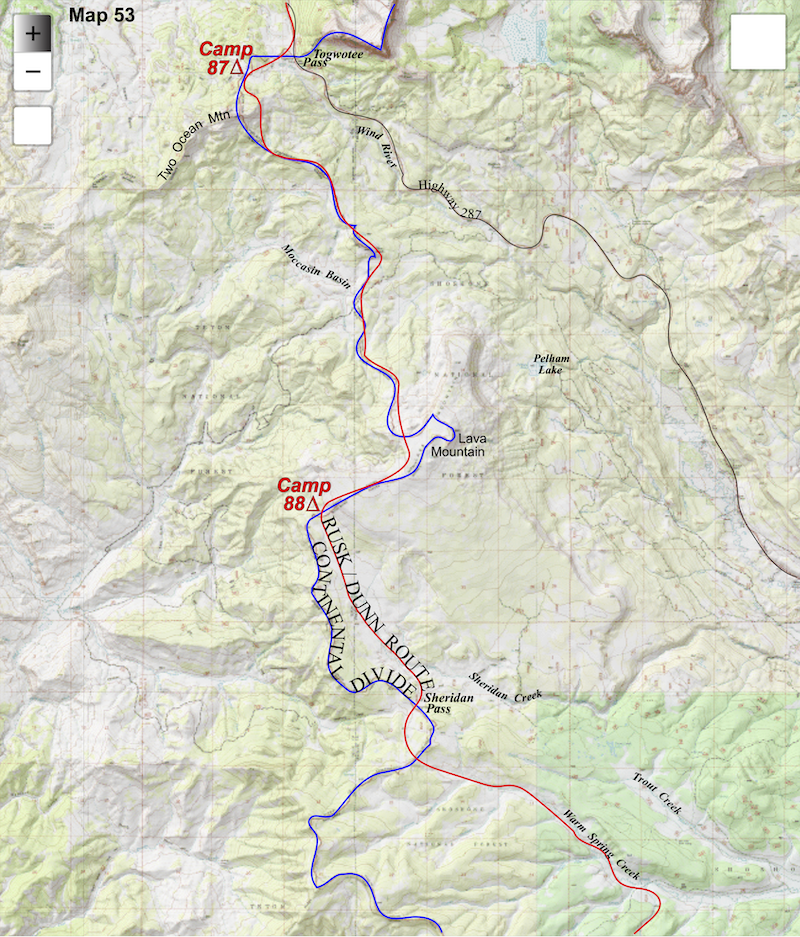

There it all was, rolling tundra and shimmering peaks in the not-so-far-off distance, just out there waiting. From the boulderfield, we worked our way down off Lava Mountain through open timber out into rambling, sagebrush pastures where we finally made camp along Sheridan Creek. It had been an Olympic training day from the minute we broke camp and we had made the grueling haul for as long as we could possibly stand it. The next morning we navigated our way down and across Sheridan Pass through more highland pastures and range cattle, reaching Warm Spring Creek early in the afternoon. By now the sun was glaring and It was hot, sapping away at energy I needed for other things, like carrying the pack, and I could tell already it was going to be another dog-it-out afternoon. We followed along the creek through open pasture out to a short piece of dirt road which then took us to a trail, leading steeply up the last 3 miles to Fish Lake. Were it not for the weight of our packs, the backpacking through this stretch could have been enjoyable but as it was, by the time we reached the lake, the hip belt on my latest renovation, internal-frame pack was mashing my innards, the shoulder straps were compressing grooves into my shoulders and the sternum strap across my chest was making it hard to breath; it was time to dump this pig.

continued in our favor and the morning was brisk and alive with plenty of fresh, mountain energy in the air. Our overall route planning for the Wind Rivers had included a couple of short days and one rest day so we would have some recovery time along the way, and today was a short hike on easy terrain to Lake of The Woods. As we started off I could feel my pack was just a titch lighter and I could tell my lower power source had kicked-in a few extra ‘mule’ muscles to make the hiking a little easier. We climbed up out of the Fish Lake Valley to reconnect with the Continental Divide on an open, rambling ridge with a good trail. Despite the weight of my pack, the hiking was pleasant and there were no radical elevation changes to deal with, just ambling terrain with awesome views and perfect weather all around. The trail eventually took us through a stretch of lush, evergreen forest before finally arriving at the shoreline of Lake of The Woods.

We settled in at the top of a knoll just as the deep yellows and oranges in the sky were giving way to a golden hue, with the sun hovering just above the skyline. We began to glow, literally, as alpine glow slowly lit up the hillside. Then, out of thin air, Craig produced a joint in his hand. Well hello, daddio! “Where did that come from??” I asked, completely surprised. Remember the guy we’d watched getting busted for selling pot while we were in Jackson Hole? Well, we had bought a couple of joints off that dude earlier, before his internment, but I thought what we had was toast by now. “I found it on the trail” Craig replied, grinning as he fired it up. Now we were really all aglow as the sunset’s artistry became magnified. We basked in the fleeting alpine glow until the sun vanished and dusk’s chill began to settle-in. Deciding it was time to head back to camp, we hiked back down the meadow we had come up then, not far from the lake, we entered into some scattered trees.

good 20 to 25 yards from reaching any climbable trees, and in that sudden, branch-bashing instant when the moose exploded out of the dark, Craig and I both leaped into the air and shot off in a bolt-sprint for the nearest trees, instinctively splitting our path to create confusion for the moose. There was a flash out of the corner of my right eye, which was Craig, and the pounding, crashing sound of impending harm right at my back, when the next thing I knew I was 15 feet up in a tree and the moose was thrashing around some 30 feet away, trying to smash Craigs feet into the trunk of his tree. Craig jerked his feet up and the moose missed, giving Craig a few extra seconds to scramble for higher branches. With Craig now out of reach, the moose turned and started assaulting my tree. The beast kept raging between the two trees, madder than holly hell. I’d heard stories of people being treed by moose that refused to leave for more than a day, so I didn’t know, maybe I was going to spend the night up here. We waited and waited while the moose rutted and stomped between our two trees until it was dark and cold. We’d been perched up in the branches for maybe a half an hour, which seemed more like several hours, when the moose finally gave up, snorted and left. So, the moose was out of sight and the forest was quiet again, but we were both reluctant to climb down out of our tree. And then, once on the ground, we still had to work our way around the lake back to camp through the now pitch-black forest and, at this point, I was not only seeing moose behind every tree in the dark, but grizzlies, pumas and Bigfoot as well. Finally back to camp, we joked about the moose incident the rest of the evening, having laughs over the immaculate ‘levitation’ we had executed up into the trees and Craig, being 6’5”, having to whip his feet up before the moose smashed them against the tree; it was all like a slapstick comedy to us now.

The late afternoon sun shadowing the Tetons shone across the Snake River Valley to cast alpine glow on the northern tips of the Wind River Range and clouds gliding under the sun created specters of moving light across the valley. We sat silent in camp. I was lost in a hundred mile stare, looking out at nothing but everything and feeling whittled down to a naked, nano-spec of whatever it was that was me. I was anxious in a way that I had not felt since the early weeks of the trip, and yet, I knew I should be really stoked about what was out in front.

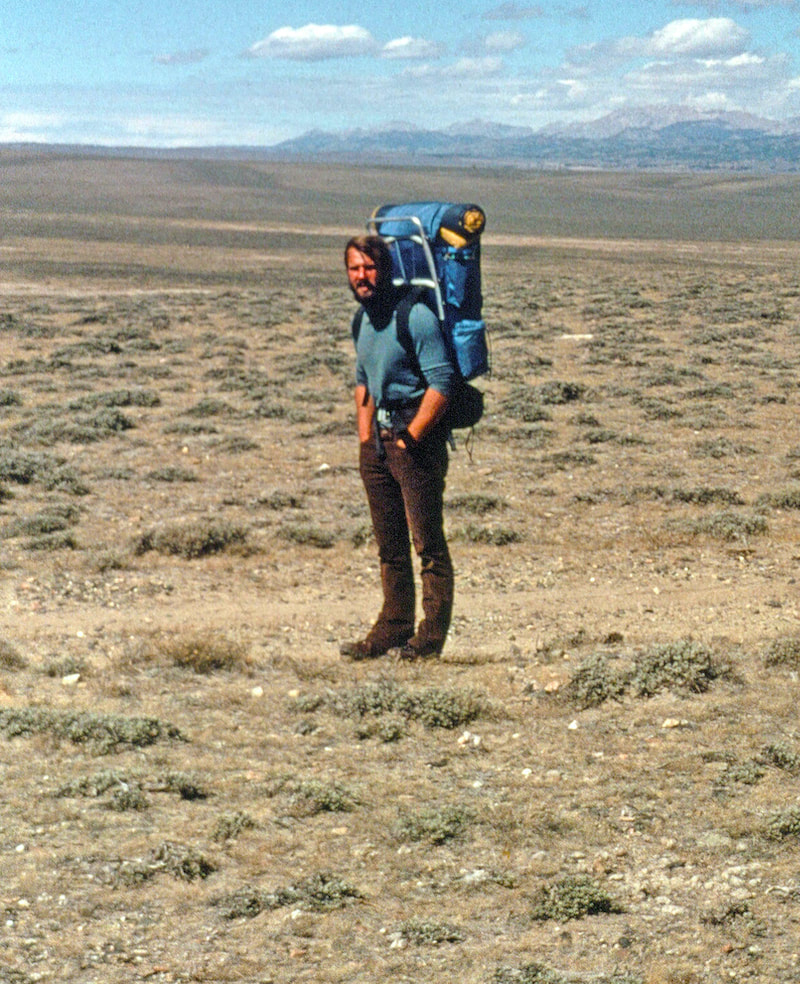

climbing the Rocky Mountains had to offer, and most of it ran straight down the ridgeline of the Continental Divide which, per our specifications, would also be ‘the strictest line possible.’ So, that’s what we had planned for. And we did so in spite of the fact that the maps also showed a north/south trail system running along the toe of the peaks that would have made for a pretty logical backpacking route. the extra pounds necessary for climbing the miles of glaciated and rock-splintered ridgeline. Then, adding more weight and bulk to our packs was the warmer clothing we would need. Our plan also had us exposed us to autumn winds and weather at high elevations so we needed hats, gloves, mittens, shell parkas and extra wool clothes. Throw in two weeks’ worth of non-freeze dried food stuff and all the other backpacking crap we needed and our packs had ballooned into insufferable pigs, approaching the weight of a 100lb sack of cement. We were certainly strong, strong enough to shoulder the load, but by now our bodies were also fairly worn and tired from the previous 1,200 miles and this challenge here, in front of us now, was going to be an ordeal. I really didn’t know if we were strong enough to pull this off or not, but I had a feeling fantasy was about to have a head-on collision with reality. That first morning heading into the Wind Rivers was crisp, clear and, seemingly overnight, autumn colors had burst out all across the high country. We didn’t anticipate much in the way of trails at the outset so we started off cross-country, through open forest and rocky, highland pastures. typically skirt our way around a heard. Today, however, our packs were too heavy to play dosey-doe around the pasture with these hoofed hamburgers, so we just kept our heads down and maintained our direction with a slow, plodding pace until the cattle were behind us - which worked out surprisingly well. we came up onto the top of a massive slope buried in boulders. Looking down at all that chaos we’d have to descend with this dead pig on my back made my mojo sag. Descending the boulderfield was tedious, time consuming and unexpected, since I didn’t think we’d see this kind of terrain just yet. But there was something else I noticed that was more troubling; when I reached the bottom of the slope and looked back for Craig, he was still far up the hill and plainly struggling to fight his way down through the boulders. I sat down on a rock to wait. Craig wasn’t lagging because he was slow, it was more serious than that. My mind was starting to question how we should proceed, our entire plan right now depended on our ability to move through this kind of terrain with some semblance of speed. In another day or so our entire world was going to look like this, for days, and a lot of it was going to be much harder than coming off Lava Mountain. Craig finally joined me at the bottom of the boulderfield and propped his pack against a large rock to relieve his load and take in the afternoon view. There it all was, rolling tundra and shimmering peaks in the not-so-far-off distance, just out there waiting. Go to Part 46

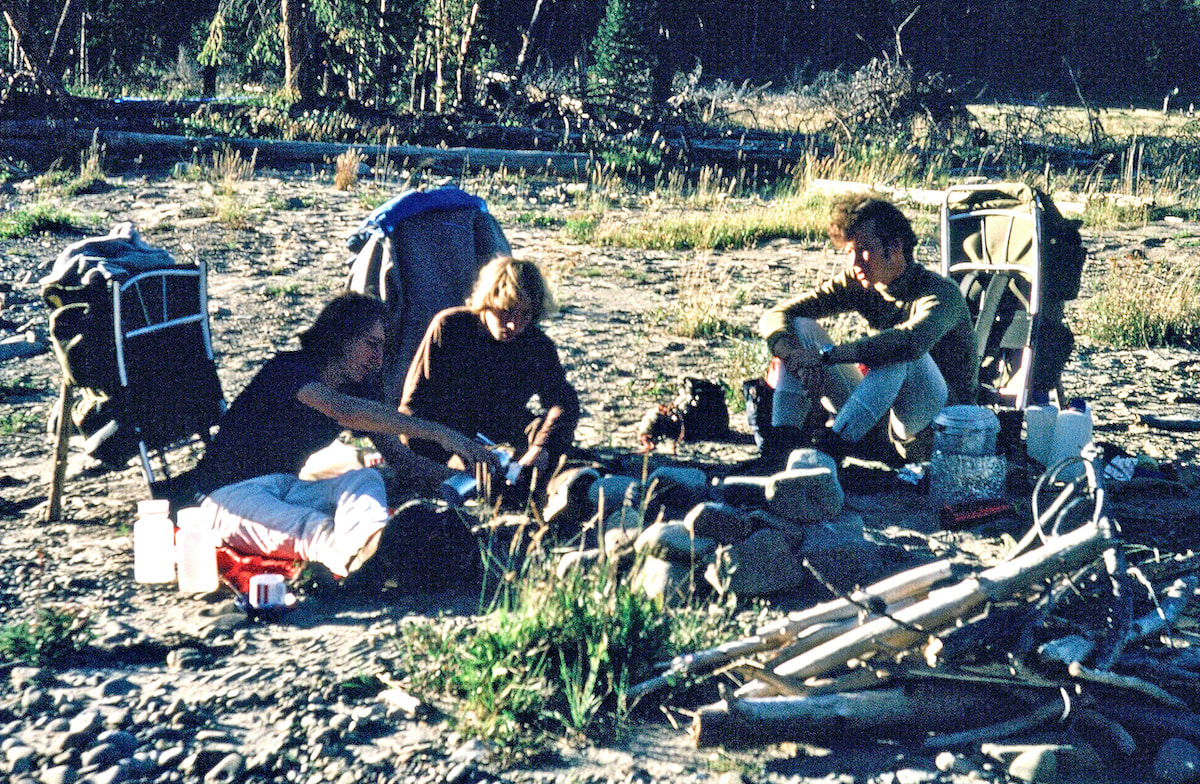

August 26th - 28th Jackson Hole, WY (Go to Pt 1) Now we’d have to hitch-hike to Jackson Hole from here; all four of us dirty, smelly, hippie types, complete with our four, over-sized backpacks. Craig and I already knew how hard it could be for just two, dirty, smelly, hippies with over-sized packs to catch a ride, so getting all four of us to Jackson Hole was going to be interesting.

The engine noise inside the hollow tube of the bus made it too loud for chit-chat, so we just bounced along, completely content to watch the scenery roll by as the bus motored along with the miles-upon-miles of cars and RVs that were strung all the way from Moran Junction to Jackson Hole. We arrived in town around mid-afternoon. The bus driver pulled over at a street corner where I started to dig through my pack for some cash to give the guy, but he just smiled and waved me off. “Have a safe trip, fellas.” he offered as we deboarded. “Thanks, man!” I don’t quite recall just how Dave and Murry left town, maybe I was too distracted trying to find the Post Office or something, but apparently they found a bus out of Jackson Hole because they did eventually turn-up back home. In retrospect, I was rather amazed and really quite impressed at how quickly those two had adapted to the rigors of Divide hiking and how well they had looked out for themselves and each other throughout the entire trip – including the last part where I wasn’t paying much attention and they got themselves back on a bus headed home. The greensticks had earned their stripes the hard way and were greensticks no more. Craig and I were doing a resupply and equipment change-over in Jackson but the box with the crampons, ice axes and warm clothes did not arrive with the food box and we were going to need that gear for the Wind River Range. As a result, we spent two days loitering around Jackson Hole waiting for the box arrive. If we’d had some cash to splash, Jackson Hole would have been a rip-roaring good time. But since we didn’t, we spent our time in the park watching tourist stream in and out of the Silver Dollar Bar – which had its moments, particularly the late night pot bust that nabbed one guy right there in front of us as we lounged at our picnic table. That was pretty exciting. The box with our gear finally arrived and we did a hasty change-out of equipment in the post office parking lot, boxing-up our lowland gear to send on to Lander where we would need it next for the Red Desert. The hitch-hike out of Jackson was exceptionally tedious, in part because there were so many cars on the road that even those inclined to stop were hesitant to pull out of traffic. But the bigger problem was that we weren’t the only hitchhikers trying to get out of Jackson Hole on Hwy 191, by the time we’d walked out to the city limits there was already a que of dirtbag hippies and one golden retriever ahead of us. And then, to really knot things up, there were strict rules involved with hitchhiking because hitchhiking was illegal and closely patrolled in and around Jackson. This being the case, and since hitchhiking was such a problem in Jackson Hole, the city had set-up a bench at the edge of town with a sign above it depicting a ‘hitchhiking thumb’ where prospective ride-sharers would sit, pleading with their eyes for a ride. The posted rules under the thumb were clear, one could not stand within so many feet of the roadway and the use of signs or hand gestures to flag down cars was strictly prohibited; doing any of the above came with a hefty fine which nobody reduced to hitchhiking could possibly afford. Both the town cops and State Patrol drove by regularly, so us dirtbags on the bench tended to mind the rules, bonding together as refugees do, patiently waiting for our turn under the thumb. After a long afternoon on the bench, Craig and I finally got to the front of the que under the thumb then waited and waited with our two monstrous packs for a short ride back out to Moran Junction. From there we walked/hitched to Togwotee Pass, arriving before sunset with just enough time to hike out and make a camp. The late afternoon sun shadowing the Tetons was shining across the Snake River Valley to illuminate the northern monoliths of the Wind River Range and clouds gliding under the sun created specters of moving light across the valley. We were finally heading into the Wind Rivers, a range of mountains that we had been anticipating with both eagerness and trepidation for over a year now. Go to Part 45

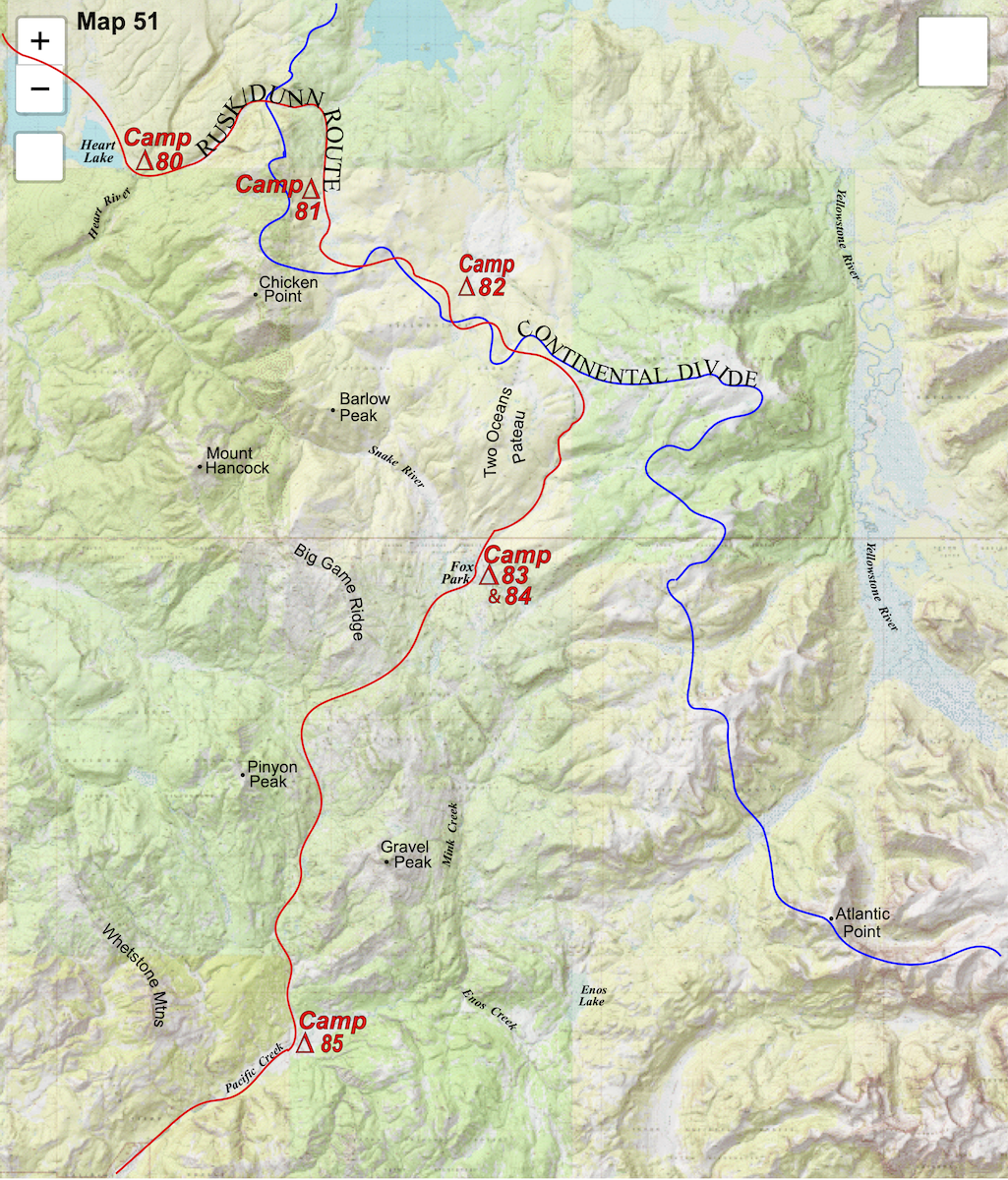

August 23rd - 25th Yellowstone National Park (Go to Pt 1) The next morning dawned warm and sunny and we set about packing our gear and tidying up the cabin early. But before leaving, we wrote a brief note to the Ranger explaining why we had broken-in (Murry’s plight and the ‘severe’ weather), apologizing for the broken windowpane, and finishing the note with an address where they could send the bill - my parents’. That done, we set off down Fox Park. Shortly after leaving the patrol cabin, we came across a sign for the Snake River trail leading out of Fox Park which we followed up into another, rambling forest of lodgepole pine. The sky was a brilliant blue and the sun was out in full shine but following the cold front, the air was much cooler now. We kept a steady but unhurried pace as the trail gained elevation then began to weave its way back down along Gravel Creek. Around mid-day we stopped for a leisurely, picnic lunch along the lakeshore of Gravel Lake, even dozing a bit under the warm sun, before saddling the packs and continuing on to camp.

The next morning rolled-in bright and fresh and, unforeseeable catastrophes aside, we would be out of Yellowstone by day’s end. Once the boys heard Craig and I crunching around camp, they got to bustling about inside their tent, getting sleeping bags and gear stowed back into their stuff-sacks, then booting-up for the day. After breakfast was cleaned-up and as I was finishing my packing, I took a glance over to see how Murry and Dave were coming along and it was like ‘well, shit’dang!’ I could hardly believe my eyes – they were done, ready to go, and looking at me like ‘Hey, what’s the hold-up over there?’ I thought those two had looked uncharacteristically energetic throughout the morning and now I could see why, they had been hell-bent on being the first ones ready to leave camp, and I think they may have also been hell-bent on getting this fucking trip over with. The day out in front of us looked to be little more than a long meander down Pacific Creek with probably four or five river crossings to be made. The river was shallow and dry rocks were exposed all the across, so when we came to the first crossing, I hardly broke my stride rock-hopping over to the far side. Once I reached the bank, I looked back to see Craig making a slow-hop across, stopping to show Dave and Murry the correct stones to follow. Oh yeah, I’d forgotten about those guys. So, when we got to the next crossing where the river was a tad narrower and the rock-hop a bit trickier, I stopped to wait for the boys.

I went across first, demonstrating flawless technique, no doubt, then Dave gave it a shot. Well, Dave got out to the second rock when his right foot slipped, causing him to scramble like crazy to get atop the next rock where he lost his balance again, precipitating a lurch forward to the next rock which, after such a great effort, he completely missed, leaving him up to his shins in whitewater with both boots in. Bummer. His waterlogged boots were going to weigh about 10 pounds apiece for the rest of the afternoon. Ah well, it’s not like I hadn’t dunked my boots a few times along the way; I could sympathize. Murry went next and, sure as shit, proceeded to slip on the same rock Dave had. Excepting him to scramble back on top of the stone, I was surprised when Murry just stood there with this silly smile on his face, one boot in the river and the other still on dry rock. As we continued down Pacific Creek, Murry saw no reason to alter his boots-on, through the river approach for the remaining river crossings, proceeding like he’d just discovered something no one had ever thought of before, while Dave, who was finally getting his boots to dry a bit, made every effort to stay out of the water like a just dunked cat. The day was neither long nor hard but all I could think about was taking a shower and having a decent meal and that right there was like dropping an anvil in my pack. And, as it turned out, the river crossings did slow us down, since finding linked rocks across the river all within a single stride of each other was time consuming but, then, I was kind of ‘inflexible’ about keeping the boots on at all costs. By the time we were nearing Moran Junction it was latter in the day than we’d planned, so I had to call a disappointing, team meeting and reluctantly tell Dave and Murry that it was too late in the day to break back-out into civilization and start hitch-hiking to Jackson.

Nobody was slow getting out of camp the next morning and we wasted little time making a stiff-clip hike out to Moran Junction, arriving to the full onslaught of tourists and tourist traffic at the south entrance to the Park sometime mid-morning. Now we’d have to hitch-hike to Jackson Hole from here; all four of us dirty, smelly, hippie types, complete with four over-sized backpacks. Craig and I already knew how hard it could be for just two dirty, smelly, hippies with over-sized packs to catch a ride, so getting all four of us to Jackson Hole was going to be interesting. Go to Part 44

August 20th - 22nd Yellowstone National Park (Go to Pt 1) Sometime mid-afternoon Murry got light-headed and wobbly on his feet and had to lie down. The rain had stopped, so at least that wasn’t aggravating the situation, but I was worried that maybe the cumulative effect of the past week had worn him down to a state of complete exhaustion.

As we trudged down the long, meandering stretch of Plateau Creek, the clouds slowly began to swirl overhead as if undecided about whether to clear out or settle back in. When the sun broke out as we were dropping down into Fox Park, it appeared the skies might actually clear but, in the end, it was just one, big sucker-hole.

It was right around this time that the clouds sunk back into the valley and started to rain, and it was like ‘Jesus, come on’, the timing could not have been worse. Now we were going to get a soaking while we wandered around in search of a reasonable place to pitch tents. We continued down the trail running along the valley floor when we rounded a bend and I noticed a Forest Service patrol cabin just up the hill from us, tucked in amongst some pines. My immediate thought upon seeing this little refuge was ‘Woah, wouldn’t that be nice!’ We all walked on up to the cabin and found the windows shuttered, so I dropped my pack and stepped up onto the stoop to try the door, locked. Well, alrighty then! “Hey,” I called over “it’s empty! All we gotta do is find a way in!” This, of course, was met with the full and enthusiastic support of the group. No doubt, we were facing federal prosecution by breaking into government property, but I don’t think any of us really gave a rat’s ass as we scattered around the building looking for a weak point of entry. Damn! It was literally varmint proof. Going through a window finally appeared to be our only option and the shutters were latched from the outside, so that part was easy, but getting the window to ‘shimmy’ open didn’t go so well and, unfortunately, a glass pane broke in the process. Well, there was no turning back now, reaching through the broken glass I was able to get the window unlatched and crawl through to the inside and we were in! Honestly, given Murry’s exhausted state and the appalling weather, this cabin was a real godsend. The tiny, woodland cabin was very similar to other patrol cabins Craig and I had visited along the way; a neat, made-up bunk by the window, a picnic style table with two benches near the center of the room and tidy cupboards stocked with a few canned goods. We got Murry comfortable and hot drinks going on the stove then Craig and I set about getting all the damp and wet gear out of everybody’s packs to dry. would be no extra charge for another night, those felonies had already been committed. The cabin day lightened everyone’s mood and the rest was more than necessary for Murry and Dave who had practically walked themselves to death without complaint. A deck of cards was found in one of the cupboards and the highlight of the day (or lowlight depending on your hand) was playing poker for caramels. Now, first off, don’t think those caramels were merely tokens. Food stuff of any kind out here was valuable, but caramels were like gold, carefully rationed and enjoyed only in moments of quiet repose. Everyone had been allotted two caramels per day for the trip and by now we were all running low. Craig and I figured playing poker with these two high schoolers for their candy would be like, I don’t know, taking candy from a couple of high schoolers, I suppose, and we wanted their caramels. As the game gained momentum, scoring a few caramels, or losing a couple, made each hand increasingly edgy and passions began to run high as the greensticks started winning my stash. By the last hand Dave and Murry owned most of the caramels, leaving Craig with just a few and me with only one; I was facing total ruin. Poker-faced Murry beat whatever I had, and I’d have to say that I was just a little bit chagrined when he snatched up my last caramel. And then, ‘poker-face’ Murry morphed into ‘in-your-face’ Murry pretty darn quick. Sitting across the table from me, he looked like the cat that just ate the canary, grinning from ear to ear as he recklessly ate a caramel right in front of my face then blatantly offered another one to Dave. Those little rat-bastards! I wanted at least a couple of my caramels back, but no amount of cajoling, begging, or threats of revenge succeeded in getting even one of them back. The boys had triumphed and simply laughed at my pleas for compassion as they squirreled away my lost fortune, and the thought of going carameless for the remainder of the Yellowstone stretch really chapped my ass. Karma, yeah, I know.

|

Kip RuskIn 1977, Kip Rusk walked a route along the Continental Divide from Canada to Mexico. His nine month journey is one of the first, documented traverses of the US Continental Divide. Montana Part 1 - Glacier Ntl Pk Part 2 - May 11 Part 3 - May 15 Part 4 - May 19 Part 5 - May 21 Part 6 - May 24 Part 7 - May 26 Part 8 - June 2 Part 9 - June 5 Part 10 - June 7 Part 11 - June 8 Part 12 - June 11 Part 13 - June 12 Part 14 - June 15 Part 15 - June 19 Part 16 - June 23 Part 17 - June 25 Part 18 - June 27 Part 19 - June 30 Part 20 - July 5-6 Part 21 - July 7-8 Part 22 - July 9-10 Part 23 - July 11-15 Part 24 - July 17-18 Part 25 - July 18-19 Part 26 - July 19 Part 27 - July 20-21 Part 28 - July 22-23 Part 29 - July 24-26 Part 30 - July 26-30 Part 31 - July 31-Aug 1 Part 32 - Aug 1-4 Part 33 - Aug 4-6 Part 34 - Aug 6 Part 35 - Aug 7-9 Part 36 - Aug 9-10 Part 37 - Aug 10-13 Wyoming Part 38 - Aug 14 Part 39 - Aug 15-16 Part 40 - Aug 16-18 Part 41 - Aug 19-21 Part 42 - Aug 20-22 Part 43 - Aug 23-25 Part 44 - Aug 26-28 Part 45 - Aug 28-29 Part 46 - Aug 29-31 Part 47 - Sept 1-3 Part 48 - Sept 4-5 Part 49 - Sept 5-6 Part 50 - Sept 6-7 Part 51 - Sept 8-10 Part 52 - Sept 11-13 Part 53 - Sept 13-16 Part 54 - Sept 17-19 Part 55 --Sept 19-21 Part 56 Sept 21-23 Part 57 - Sept 23-25 Part 58 - Sept 26-26 Colorado Part 59 - Sept 26 Part 60 - Sept 30-Oct 3 Part 61 - Oct 3 Part 62 - Oct 4-6 Part 63 - Oct 6-7 Part 64 - Oct 8-10 Part 65 - Oct 10-12 Part 66 - Oct 11-13 Part 67 - Oct 13-15 Part 68 - Oct 15-19 Part 69 - Oct 21-23 Part 70 - Oct 23-28 Part 71 - Oct 27-Nov 3 Part 72 - Nov 3-5 Part 73 - Nov 6-8 Part 74 - Nov 9-17 Part 75 - Nov 19-20 Part 76 - Nov 21-26 Part 77 - Nov 26-30 Part 78 - Dec 1-3 New Mexico Part 79 - Dec 3-7 Part 80 - Dec 8-11 Part 81 - Dec 12-14 Part 82 - Dec 14-22 Part 83 - Dec 23-28 Part 84 - Dec 28-31 Part 85 - Dec 31-Jan2 Part 86 - Jan 2-6 Part 87 - Jan 6-12 Part 88 - Jan 12-13 Part 89 - Jan 13-16 Part 90 - Jan 16-17 Part 91 - Jan 17 End |

© Copyright 2025 Barefoot Publications, All Rights Reserved