The Continental

|

Once the tent was pitched we started unloading our packs, tossing stuff into the tent and, in my case, digging furiously through the sack for my coveted camp booties. Getting those goddam boots off my feet was a luxury all by itself. Once I’d slipped into my camp booties it was important to keep moving because the urge to ‘just sit down for a minute’ was huge, and then one minute would turn

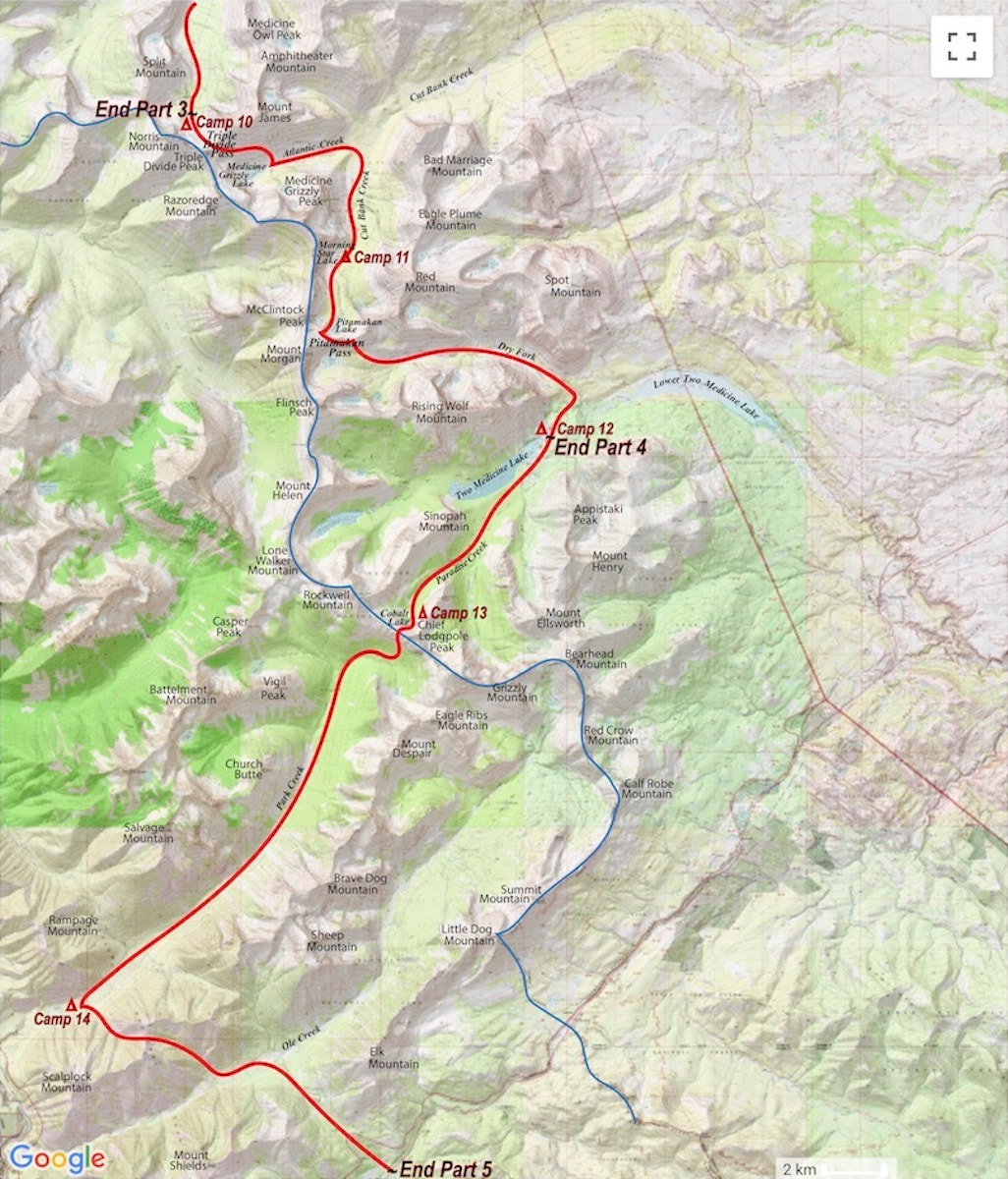

Except this night when my mind refused to shut off. I lay restless and unsettled, listening to the wind howl over the ridge in the distance and come down the valley to incessantly snap at our nylon tent fly. As I lay there, various scenarios of gloom and doom played out in my head: avalanches, bears, crippling falls, river drownings, running out of toilet paper; stuff that would roust me just as I started to doze. Then, when morning finally did come, it was all dismal grey and pissy outside. It was a miserable morning of craping in the freezing-ass rain and packing away damp and wet gear. And then there were those pit-bull boots of mine, now with the added charm of being both cold and wet. I laced up the miserable bastards, strapped on the Bear Paws and loaded on my pack. From our camp we had almost 2,000 feet of elevation gain with several terrain problems to negotiate before reaching Pitamakan Pass. The climb from Morning Star Lake into the upper basin was steep and exceedingly laborious as the snowshoes punched through breakable wind crust at almost every step. It was a brutal go and we swapped out turns breaking trail often, grinding out every foot of elevation gained. Just below the upper basin we came out onto a steep, open slope still holding a potentially unstable wind slab. I didn’t see an obvious route around it without getting blocked out by a cliff band above and, once again, the direct route across the slope begged us to roll the dice. Avalanche safety equipment for us in 1977 included a 100 foot length of red parachute cord, a couple of transceivers, a probe pole and a small shovel. The parachute cord tied around your waist and trailed on the snow behind in the hope that if you did get caught in a slide some of the cord would be visible on the surface of the avalanche debris which would allow a rescuer to pull up the cord and follow it to the victim. The avalanche beacons we had would transmit a signal from a buried victim to what would hopefully not be another buried victim but presumably someone standing close by who could come locate you. Essentially, what we carried amounted to body locating equipment. Anyway, the siren song of the upper valley was calling from just the other side of the slope. We doled out the cord, switched on our beacons and preceded one at a time across the slope; I volunteered to go first. I tried my best to float the crust but punching my boots through was inevitable and the whole thing just grew scarier and scarier the further out across the slope I got. Near the middle I suffered a wave of panic and almost turned back but didn’t and kept going until the boulders were close enough to where I tried to run but pretty much stumbled the last twenty yards to safety. I dropped my pack, sat down on a boulder and looked back across the slope. Now Craig had to cross and there was a pretty good chance that the punched holes I’d made in the slab had left the slope even less stable than before. And I really didn’t want to watch my buddy go down in an avalanche. Craig tentatively ventured out onto the slope and stayed in my boot prints like he was navigating a mine field, not wanting to disrupt any more of what was still holding the thing together. Once he got committed though, he started to move across the slope with more urgency and also ran-stumbled the final yards to the finish. We re-grouped like friends who hadn’t seen each other in a long while and then headed on to the top of the ridge. Turning the crest of the ridge into the high cirque created by McClintock Peak and Mount Morgan was a cold smack in the face. In a matter of a few paces we stepped from a warm, calm day on the lee side of the ridge right into an icy and brutal wind on the other side; the same howling gusts that had blown through our camp in the night. Here, the wind had scoured the basin clear of snow such that the barren, rocky trail now meandered out in front us, skirting Pitamakan Lake to the base of Pitamakan Pass. At the base of the pass we found a large boulder that afforded a measure of protection from the wind and stopped to put on crampons and unstrap the ice axes.

From the south side of the pass, the descent into the Dry Fork Valley looked pretty straight forward and, although there was more snow on this side of the pass, it was also softer, so we elected to forgo the crampons but keep the ice axes handy. As we descended we weren’t paying close enough attention to the nuances of the terrain and unwittingly got drawn into a narrowing gully that offered easy passage at first but then began to steepen. By the time we realized the gully was going to cliff-out below us we were looking at a monstrous climb back up to get out. So we gingerly worked our way down to the cliff’s edge to take a look. I didn’t like the idea of trying to rappel down the cliff band because of how unwieldy the packs would be and especially because there was so much loose rock everywhere. I was hoping we could find another way without relying on the rope. And sure enough, there did appear to be a way to get down through the cliff band but not with the packs on our backs. We took a break while we considered this next option of down climbing about 100 feet of shattered 5th class rock and lowering our packs. Well, we sure as heck weren’t going back up, so we went ahead with the whole circus show of Craig lowering our packs down this loose, junky chimney and me climbing up and down like a yo-yo, freeing the packs from getting stuck. At the toe of the cliff there was a steep snowfield of maybe a hundred yards that fed off at the bottom into a talus slope atop another cliff band. We had coiled and strapped the rope back on Craig’s pack and I had just pick-up my ice axe to start the traverse across the top of the snowfield when both feet suddenly slipped out from underneath me and I began to slide down the slope. The immediate acceleration was alarming as I struggled against the pack to turtle roll off my back and get my axe pick into the snow. I finally got rolled over and made purchase with my axe but the snow was so soft I wasn’t slowing down nearly as quickly as I had hoped. When I finally did come to a stop my feet were resting in the talus rocks at the bottom of the slope. Craig urgently yelled down “Are you OK?” I had started picking myself up out of the snow and yelled back “Yeah, I’m OK”. Then he starts laughing and yells down “what are you doin’ down there?” “I don’t know, practicing my self-arrest, I guess” I mumbled to no one. We descended the rest of the way down to the Dry Fork Valley without further incident and dropped below the snowline out onto the trail. A few miles down the path we spotted a Grizzly Bear ambling along out in front of us; he must not have caught our scent because he didn’t seem to notice we were in the rear. We didn’t follow but stayed still and a minute later something turned his attention down the hill and he ambled off toward the river. We ended up making camp that night at the Prey Lake Campground which came complete with Winnebagos, camper trailers, dogs, kids, slamming bathroom doors, and a Park Ranger. The Ranger came by as we were setting up camp and gave us a ‘congratulations’ on almost finishing our trek through Glacier. Bob Fossen had passed the word on to the Rangers to keep an eye out for the “Divide hikers”. We told the Ranger we’d be out of the park in two more days and he said he’d let our buddy Bob know.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Kip RuskIn 1977, Kip Rusk walked a route along the Continental Divide from Canada to Mexico. His nine month journey is one of the first, documented traverses of the US Continental Divide. Montana Part 1 - Glacier Ntl Pk Part 2 - May 11 Part 3 - May 15 Part 4 - May 19 Part 5 - May 21 Part 6 - May 24 Part 7 - May 26 Part 8 - June 2 Part 9 - June 5 Part 10 - June 7 Part 11 - June 8 Part 12 - June 11 Part 13 - June 12 Part 14 - June 15 Part 15 - June 19 Part 16 - June 23 Part 17 - June 25 Part 18 - June 27 Part 19 - June 30 Part 20 - July 5-6 Part 21 - July 7-8 Part 22 - July 9-10 Part 23 - July 11-15 Part 24 - July 17-18 Part 25 - July 18-19 Part 26 - July 19 Part 27 - July 20-21 Part 28 - July 22-23 Part 29 - July 24-26 Part 30 - July 26-30 Part 31 - July 31-Aug 1 Part 32 - Aug 1-4 Part 33 - Aug 4-6 Part 34 - Aug 6 Part 35 - Aug 7-9 Part 36 - Aug 9-10 Part 37 - Aug 10-13 Wyoming Part 38 - Aug 14 Part 39 - Aug 15-16 Part 40 - Aug 16-18 Part 41 - Aug 19-21 Part 42 - Aug 20-22 Part 43 - Aug 23-25 Part 44 - Aug 26-28 Part 45 - Aug 28-29 Part 46 - Aug 29-31 Part 47 - Sept 1-3 Part 48 - Sept 4-5 Part 49 - Sept 5-6 Part 50 - Sept 6-7 Part 51 - Sept 8-10 Part 52 - Sept 11-13 Part 53 - Sept 13-16 Part 54 - Sept 17-19 Part 55 --Sept 19-21 Part 56 Sept 21-23 Part 57 - Sept 23-25 Part 58 - Sept 26-26 Colorado Part 59 - Sept 26 Part 60 - Sept 30-Oct 3 Part 61 - Oct 3 Part 62 - Oct 4-6 Part 63 - Oct 6-7 Part 64 - Oct 8-10 Part 65 - Oct 10-12 Part 66 - Oct 11-13 Part 67 - Oct 13-15 Part 68 - Oct 15-19 Part 69 - Oct 21-23 Part 70 - Oct 23-28 Part 71 - Oct 27-Nov 3 Part 72 - Nov 3-5 Part 73 - Nov 6-8 Part 74 - Nov 9-17 Part 75 - Nov 19-20 Part 76 - Nov 21-26 Part 77 - Nov 26-30 Part 78 - Dec 1-3 New Mexico Part 79 - Dec 3-7 Part 80 - Dec 8-11 Part 81 - Dec 12-14 Part 82 - Dec 14-22 Part 83 - Dec 23-28 Part 84 - Dec 28-31 Part 85 - Dec 31-Jan2 Part 86 - Jan 2-6 Part 87 - Jan 6-12 Part 88 - Jan 12-13 Part 89 - Jan 13-16 Part 90 - Jan 16-17 Part 91 - Jan 17 End |

© Copyright 2025 Barefoot Publications, All Rights Reserved