The Continental

|

|

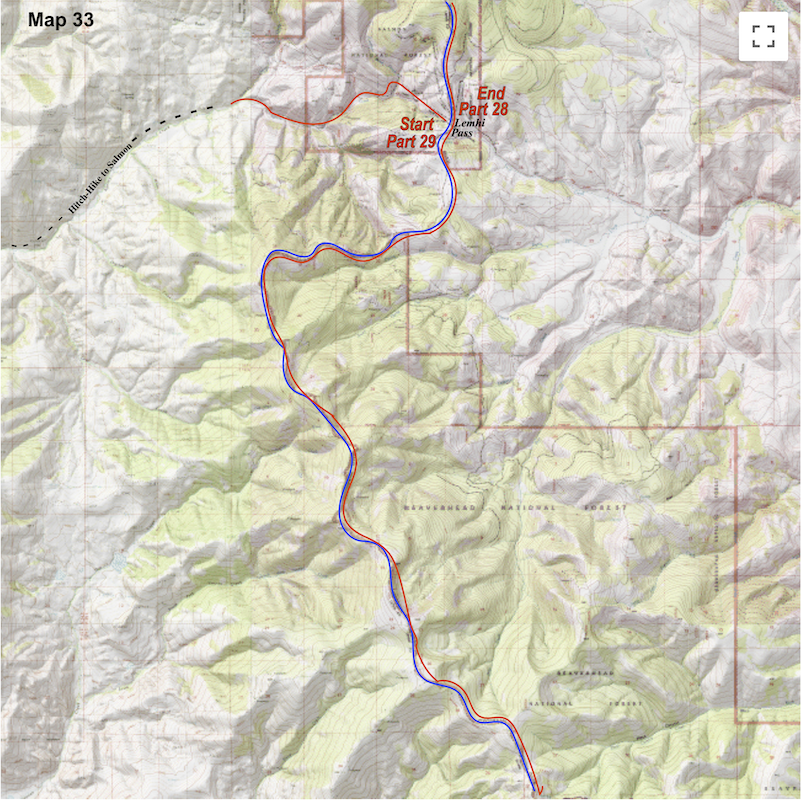

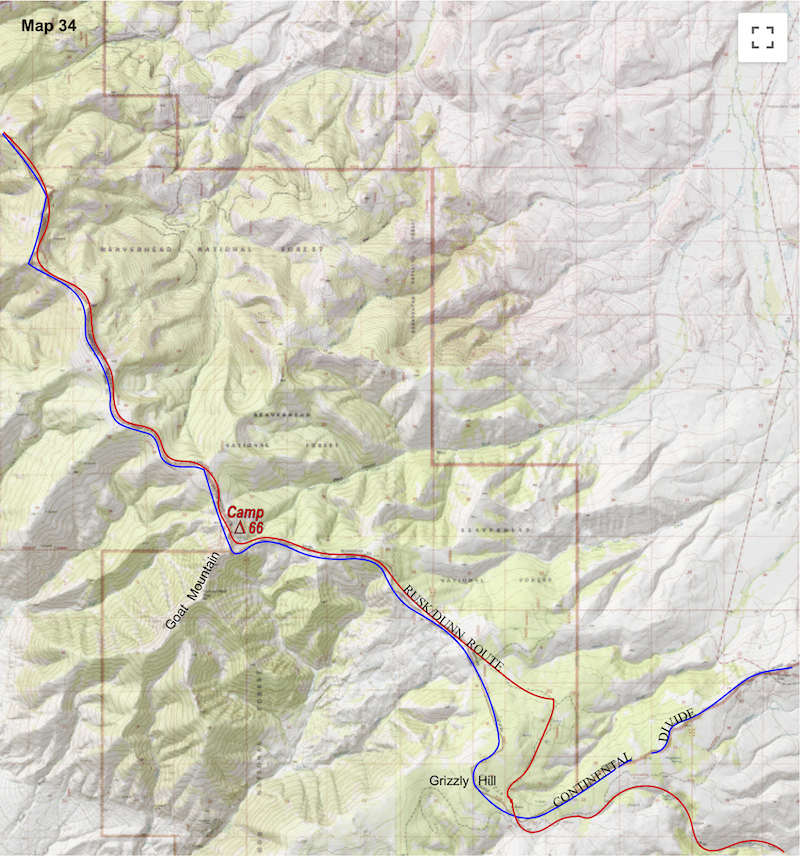

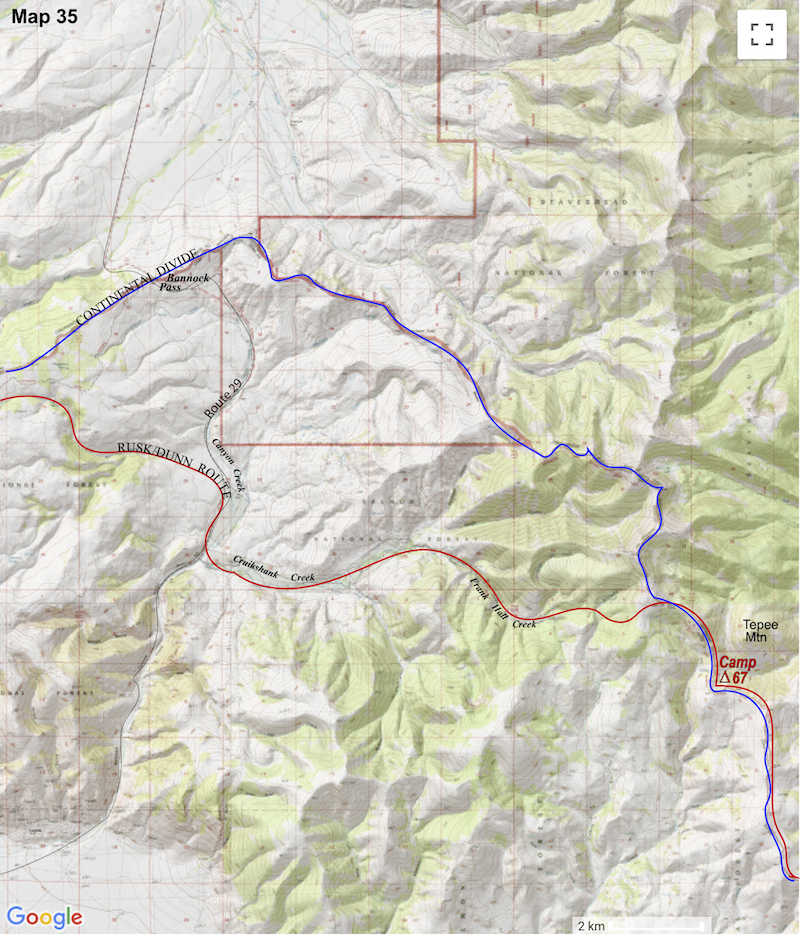

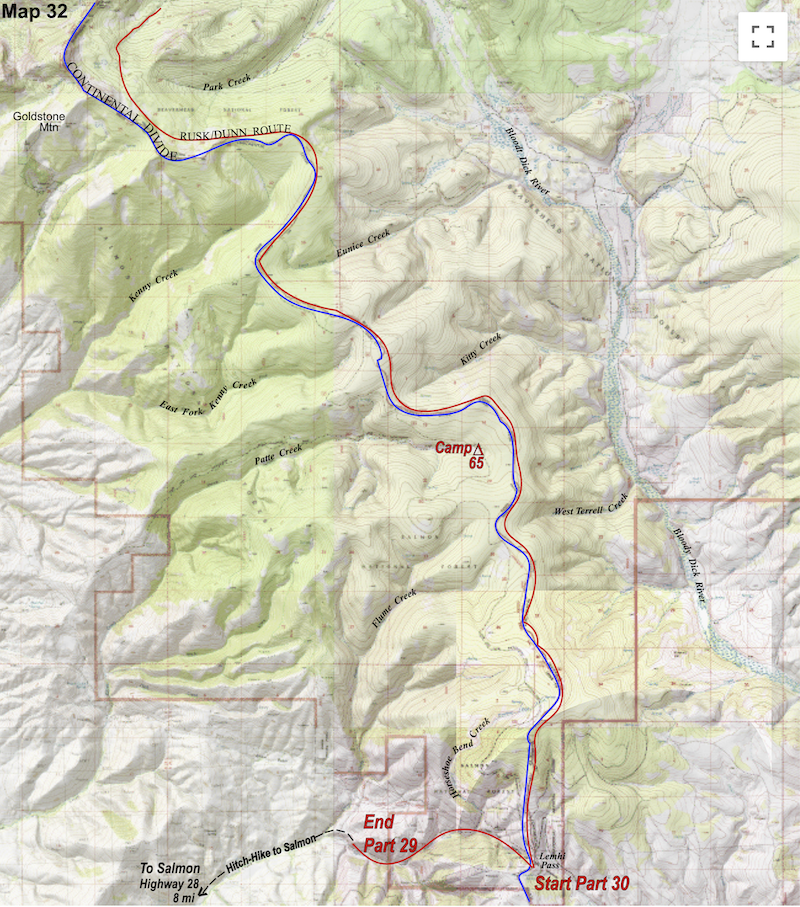

July 31-August 1 Salmon, ID (Go to Pt 1) We arrived at the top of Lemhi Pass a little after 1:00 p.m. and wasted little time getting pack-saddled and heading-off south on a hammered-out, rock and dust road that snaked its way along the crest of the Divide. Being on the front end of another two week stint meant our packs were loaded and burdensome again but we still hoped to stretch the remainder of the day out to cover at least 14 miles.

After hiking for an hour or so, the parched, sage covered slopes met up to a stand of tall pines which, in a matter of steps, closed us into a shadowy forest. Over the next eight miles or so the forest would break intermittently to afford views of differing aspects, sometimes east, sometimes west or south, as the trail ambled and undulated along the rolling crest of the Divide. Without a single obstacle in our path or any navigational worries to mind to, both the road and the terrain allowed us to accelerate our pace and move quickly along the route, which was nice for a change but also tiresome in a monotonous kind of way. Around 6:30 p.m. the road finally petered out at the saddle below Goat Mountain’s broad, north ridge. We ambled across the open, north slope and located the spring that was shown on our map then settled for a lumpy, pint-sized tent platform on the grassy hillside just up from the spring. It was a warm, calm evening with a light, summer breeze and, as we suddenly realized in astonishment, no bugs!

Earlier, while we sat eating lunch and swatting horseflies into the dirt, we watched an epic, fight-to-the-death struggle unfold right before our eyes. Several of the flies we had swatted down had hit the ground stunned, most with a busted wing or two, but not dead. Well, where there were no ants before, these hapless flies on the ground, stunned, bleeding and flailing about, suddenly brought out columns of red ants from a rotting log maybe ten yards away, marching across the pebbly gravel toward the flies. It did not take long for the ants to cross what for them was one heck of a long boulder field and engage the wounded horseflies. However, once the ants reached the killing field they quickly discovered the horseflies too aggressive and too angry for just one or even several ants to handle. It took at least ten or more ants to subdue a fly and then those ants struggled mightily as they tried to get all their combined legs to pull the bucking horsefly in the same direction. And thus, a fight to the death ensued. This was some really cool shit! I mean, when you’re out walking the Continental Divide, scenes like this are intensely interesting to watch; it was the Nature Channel Live, in HD, 3D, Monster-Vision! So, with the six or seven flies on the ground well under control, the remaining columns of ants began to march past the crippled horseflies, looking intent on bringing something else down which was probably going to be our sausage and crackers. And to be sure, once they smelled fly blood in the dirt and sausage grease in the air, they began to swarm in rapidly increasing numbers. We were pretty mesmerized by this whole insect scene going on until an ant column snuck around my left flank to reach my boot sole undetected and we were suddenly alarmed into a defcon1, lunch pack-up and rapid retreat, leaving the ants conquerors of the ground.

After a couple of miles, the track filtered out of the trees and down to a meadowy saddle, maybe a mile across, with open slopes rolling away to the southwest. Little Eightmile Creek trickled down through the meadow below the ridge, gaining momentum as it gathered down the hillside to splash its way through a series of diamond-set ponds that glittered for nearly a mile down the grassy mountainside.

We took a late lunch sometime mid-afternoon under a hot patch of shade just downstream from the headwaters of the creek. The sun was intense and I was beginning to feel weak and washed-out under the oppressive heat. I was sure the crest of the ridge was not far off but when I checked the map to see if we were close, I saw instead another 1,600 ft. vertical rise to get there; I sagged over the map and nearly puked. We had a ragged, 4W track to get us started up, out of the valley then we hung to open slopes to reach Quaking Aspen Creek. From there we trudged up a long, steady grind through hot, brittle pines to a clearing on the ridge. We dropped our packs in the dust and pulled hard on our water bottles. I was toast and my feet were pleading with me to ‘get these damn boots off!’ From the top of the ridge we only had a couple of moderately easy, downhill miles to reach camp but the thought of having to re-saddle that flippin’ pack had me pissed-off to the point of loudly barked expletives.

We spent about an hour hunkered behind the meager protection of a couple of crispy-fried, pine hags until the sun lowered enough to venture back out and pitch camp. Go to Part 32

0 Comments

July 26-30 Salmon, ID (Go to Pt 1) We arrived back in Salmon around mid-day with plenty of time to drop our gear off at the motel, shower and show up at the café for a late lunch. Imagine Zelda’s surprise! She looked almost ready to give us a hug, then second guessed the gesture, which I’m sure was wise since being seen hugging strangers in the café, strangers who may or may not be on the run from the law, might get a little gossipy around town. We settled into the booth next to the window and instantly felt like we’d never left the place. Our second stay in Salmon turned out to be somewhat extended by a visit from my Mom and Dad and a dentist appointment. When I had talked with my parents the last time Craig and I were in Salmon, they’d said they wanted to come out and meet us while we were resupplying in a town.

Apparently, I looked a bit different than the last time he had seen me, which was maybe a week or so before we’d started the trip. First off, Craig and I had both gotten those boot-camp haircuts during our previous stay in Salmon so we were sporting that military look my Dad liked so much.

While we were in Salmon we’d projected out some long range dates correlating to where we needed to be in order to reach Colorado by mid-September and I was a bit taken aback by how many daily miles we were going to have to cover if we planned to keep up with that schedule. Thus far, a twenty mile day had been a pretty big day and now this next couple of weeks was going to demand 20 plus mile days as a starting point. It was intimidating having that much daily mileage out in front of us but we had known it was coming. The route ahead was mostly defined by various types of roads and 4Wtracks crossing rolling terrain and we intended to take full advantage of these ‘easy’ miles in hopes of gaining some ground and banking some time. Go to Part 31

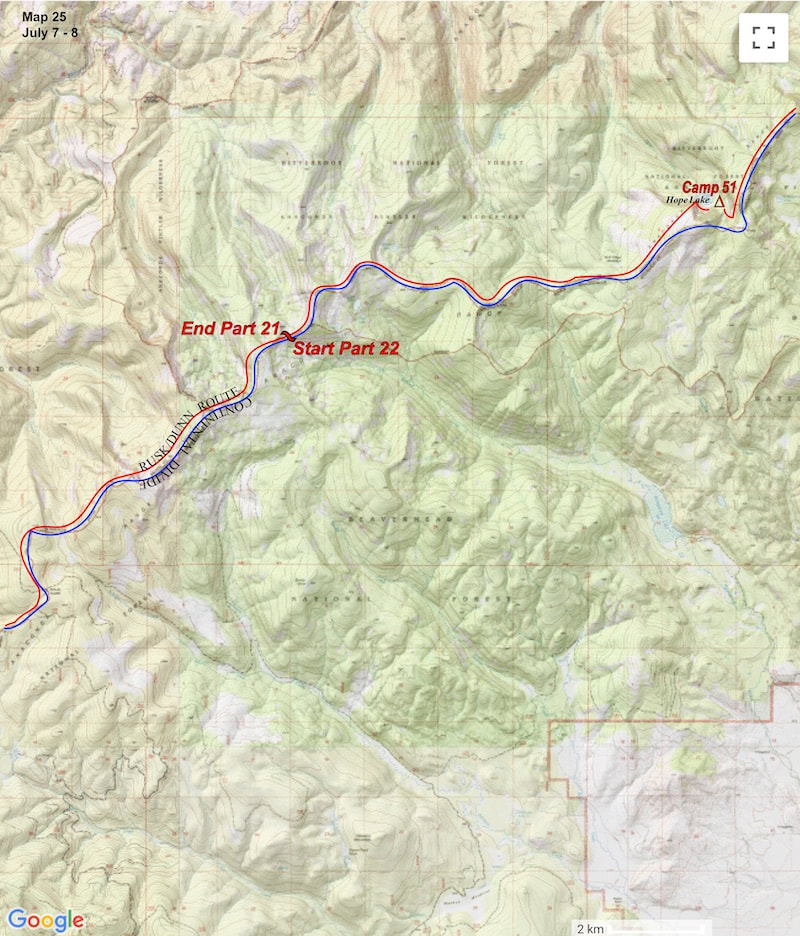

July 24-26 Bitterroot Range, MT (Go to Pt 1) The misting clouds hung low and the wet lichen growing across the rocks was now slime-slick, making the entire talus field we were about to climb significantly more treacherous. We would have called a weather delay and waited for dryer conditions but we had already spent that time lolly-gagging about the lake yesterday instead of getting the ridge traverse behind us.

Right off it was agonizingly slow going, having to test nearly every footstep for traction before carefully moving forward. And the rocks were not only slick, they were also loose, most shifting on ball bearing scree as we slip-checked ourselves one step forward followed by the inevitable half-stride slide backwards. The frigid mist obscured the upper slopes and after a while the valley below also disappeared in the mist. We managed to weave our way up the talus into the fog to a point where retreating back down the slope had become a worse option than continuing forward (happens every time when you ‘just go up to have a look’) only to then have a wet sleet start cutting its way up the opposite valley just as we reached the top of the ridge. We crossed over the ridge in an icy fog of frozen drizzle, knowing, without discussion, that our plan of continuing down the ridgeline of the Divide was over; the only question now was how out of control the decent from the ridge was going to be. We could see nothing of the descent, lost in the fog, and had no idea if we would be heading down toward the edge of some calamity or if we’d get lucky enough to find a safe route through to the bottom. The only thing that was apparent from the top of the ridge was that we had to get down and preferably without one of us taking an egg-beater somewhere in the fog below.

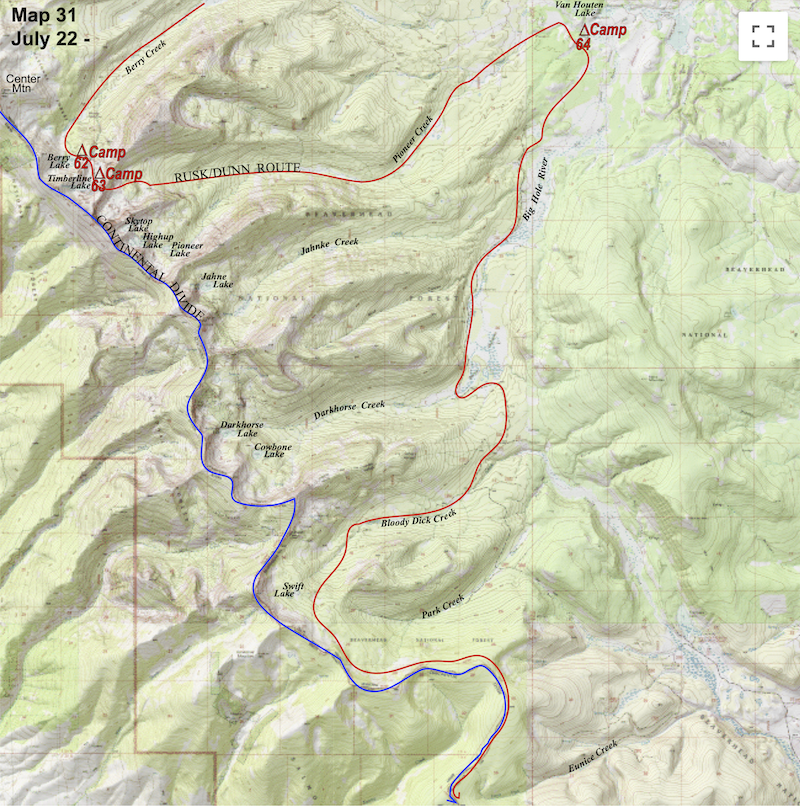

When we finally descended out of the mist and I could see that the river below was not far off, I felt confident that we’d get down the rest of the way without one of us blowing-up but, of course, no sooner did we find our way off the rock pile at the bottom of the ridge then we were doing seat-drop acrobatics down the wet, slick grasses to the bottom of the gorge. Whatever mountain fantasy we had been living in yesterday was being sharply corrected today. We collected ourselves at the bottom and now had little choice but to drop out of the high country into the low lying valley. About a mile away stood a mammoth, spur ridge that shot east, perpendicular to the Continental Divide, for almost three miles and it was just too much mountain for us to get over. The only way past this monolith was either along the Divide ridgeline to the west or all the way out Pioneer Creek for a 24 mile end-run to the east. And we’d just lost our bid at a short, ridgeline traverse down the Divide. We started the long descent from the upper valley down to Pioneer Creek, then out Pioneer Creek, eventually arriving at Van Hough Lake late in the day under a steady rain. I dropped my pack in the muddy gravel by the lake and looked around the grounds for a spot to pitch the tent that was not oozing with water but in the end, not camping in a puddle was about the best we could do. Having to set-up camp in a cold, grey rain was always a shitty way to end the day. First off, it’s cold, grey, wet and miserable and that tiny tube of nylon with its bristle of stakes is the only dry spot for miles. Our tiny tube of nylon is also the only dry place to unpack the packs and there is only room enough to do that one guy at a time, leaving the other poor sap waiting outside in the rain for his turn. Next comes the nearly impossible task of trying to keep all the dry stuff dry and all the wet stuff in quarantine. The wet rain gear, boots, gaiters, socks and packs had to go in the vestibule of the tent which was also the only place to set up the stove and do our cooking; like I said, just an overall hassle at the end of an already long, glum day. As I lay awake in the tent that night listening to the steady patter of rain on the fly it occurred to me that Craig and I had not had a single blow-up at one another since the beginning of the trip, which I thought was kind of interesting considering there were some days when we didn’t like each other at all and it would be easy to let words fly.

Time and again some brute would walk off the mat after being flipped on his back and pinned and not have a clue as to what just happened. Watching Dunn wrestle was like watching a classic bait-and-switch con; while everybody on the opposing team’s bench thought their wrestler was on the verge of a win, our guys knew what was coming, including the coach; it was brilliant! Outside of wrestling practice I saw Craig more as, well, a big brother, I guess. His irreverent humor, clever lines and hilarious story-telling were endlessly entertaining; plus, he had a sweet, eclectic collection of music and usually some smoke to go along with it. Another upper classman who had a significant impact on me, but more from a distance, was a guy named Peter Schwartz. I never knew Peter beyond campus sightings because he was a senior and I wasn’t. Peter was ridiculously handsome, a star athlete and an honor roll student who, along with a buddy of his, went out and hiked the Pacific Crest Trail from Mexico to Canada after finishing high school. The buddy dropped out not quite halfway through and Peter finished the trip alone. At that time, the Pacific Crest Trail had only just been officially established and Peter was one of the early ‘thru-hikers’ to complete the trail in one, continuous go - which really grabbed my attention. Although we lived in the mid-west, I was an all-things-mountain fanatic, mostly through books, magazines and equipment but I did get into the mountains nearly every summer, and Peter’s adventure just blew me away! Because my Dad had owned a summer business in Estes Park, CO, I had grown-up with plenty of mountain adventuring and had gravitated toward rock climbing and mountaineering at an early age. By the time I graduated high school I was armed with enough mountaineering experience, equipment and Climbing Magazine pictures to want to go out and find some real trouble. The Appalachian Trail was out there and Peter’s trek along the Pacific Crest Trail had sounded pretty outstanding but, as far as I knew, no one had ever done a thru-hike of the Continental Divide; certainly not of the ridgeline itself. Once that realization took hold the idea began to grow a mind of its own. Craig and I were both drifting after high school and hanging out together when one day we got to talking about Peter’s trip along the Pacific Crest and about what an incredible experience something like that would be. Then I told him how I was contemplating a similar trek only along the Continental Divide. Craig seemed intrigued by this idea but lacked the mountain background to really gage what is was I was talking about. Hell, I didn’t even really know what it was I was talking about. Over the months that followed, the idea would pop-up now and again and we’d banter it about until one evening I got to rambling on about what an awesome adventure it would be and finally asked Craig “So what do you think? Do you want to go do the Divide with me?” There was but a moment of hesitation before he replied “Sure, why not.” Of course, a 19 year old conjuring up big ideas in a wandering brain is practically unavoidable, what was surprising was how serious and in-sync we were when it came to both the desire and the methods for launching the idea. When we committed to putting this thing together we were both in 100% and that commitment had taken us a long way. Whether it was the trip logistics or the difficult situations we now encountered along the route, we were enough like-minded in processing the information and determining a course of action that temper outbursts were typically directed at the weather, or trail conditions, or a failing piece of gear and not each other, which was a good thing because there was little room in our day for conflict beyond the daily portion the mountains dished out. I poked my head out of the tent early the next morning to clear skies, which was fortunate because if we were going to get out of the mountains and down to town before having to make another camp, we had a really long day ahead of us.

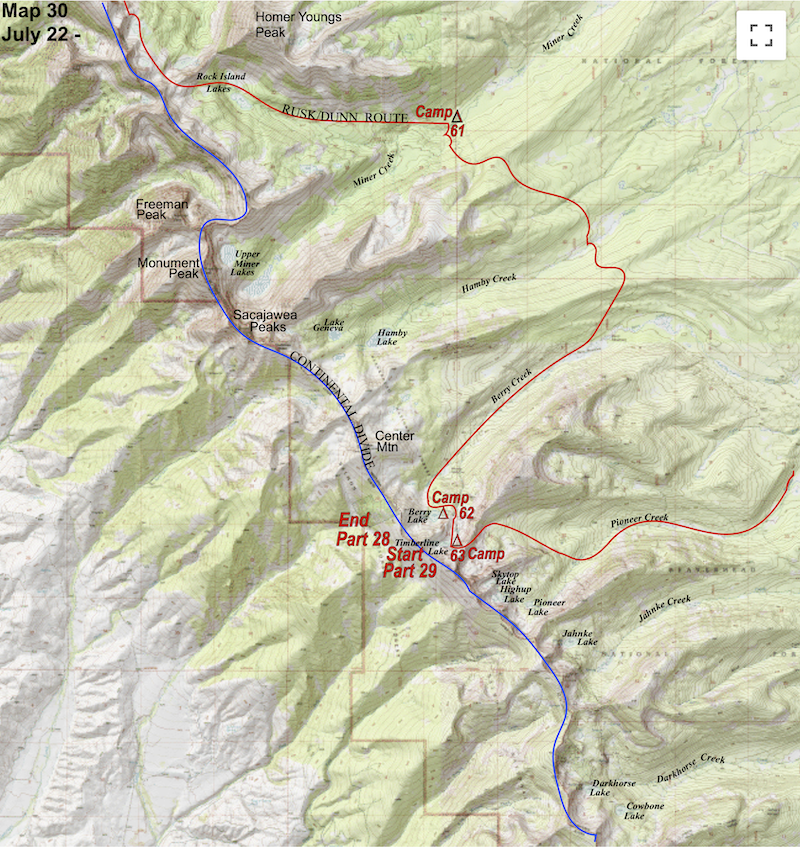

We were now hiking through open forest and, surprisingly, on a trail. Our map didn’t show a trail running along the Divide and it didn’t appear maintained or part of a National Forest trail system but we could tell it got some use by riders on horseback so we stuck with it.

couple of packets of Swiss Miss. Seems like all we talked about that evening was the Herndon cafe. The next morning we were up with the sun, more than ready to get out of the mountains and back to the café in town. What granola dust we had left we ate dry. With images of real food gnawing a hole in my brain we flew down the final six miles to Lemhi Pass. Once on the gravel road, we didn’t have to walk long before a Mexican dude in an old, beat-up ranch truck stopped and gave us a lift into Salmon.

July 22-23 Bitterroot Range, MT (Go to Pt 1) Besides the j-boys, R&C also loaded us up with plenty of good-eatin’, quickie-mart snacks and all the beer we wished to carry before we finally left their van late that afternoon. All in all, we didn’t get a darn thing accomplished that afternoon but we sure did have a good time.

of sunlight filtering through the tree-top canopy to land on every twig and leaf that held a droplet of rainfall, causing the entire stand of Cottonwoods to glisten in a rainbow brilliance that made the air itself seem to shimmer with color.

stuff. We finished breakfast, packed up the last of camp and trudged off to the base of the unnamed mountain. Fortunately, there was a well maintained, Forest Service trail we hopped-on that made easy work of the four mile climb over the ridge and down to Hanby Creek. We crossed Hanby Creek to the other side of the valley then, on the same good trail, climbed up and over another ridge, dropping us into the Berry Creek drainage. We stopped down by the river for lunch and a cat-nap before starting the trudge up Berry Creek back to the Continental Divide.

ground pass by under my feet, my absent mind flipping through a Denny’s picture menu or some other such random thing. (Fantasizing about sex was a mistake; getting lost on that topic was enough to split my head wide open and was decidedly not worth the aggravation whenever it could be avoided.) The trail ended at Moose Meadows just before the climb into the upper valley. We navigated ourselves across the remaining stretch of meadow then climbed up through open, stunted woods and finally across a short talus slope into the upper, alpine valley where we stopped to camp at Berry Lake.

blah into cleverly funny truisms. This kind of philosophical banter always helped to inject more positive energy and enthusiasm into the mission. That evening, watching the stars appear in the dusky sky, I was again struck by how lucky we were to be in this incredible environment doing what we were doing. Whatever hardships the journey demanded were worth it, so far anyway. The flowered lakeshore, the softly lapping water, the peaks overhead and the flickering stars in the deep, violet sky were all so incredibly beautiful and tranquil. The next morning we crawled out of the tent to another glorious day in the high county and busied ourselves with the morning routine. Camp nearly assembled itself with no lack of practiced efficiency and we left the lake as though we had never been there, wandering off through the meadow toward a gentle rise above the lake. We climbed a short ways and entered into a higher and even more spectacular hanging valley and apparently, according to my journal anyway, I thought I was walking onto the location set for “The Sound of Music”. In fact, that movie’s soundtrack began to sing in my head as I stood face-to-face with everything my childhood fantasy had envisioned high mountains to be like. Permeant snow glistened on the peaks towering over the small valley and the meadow was an explosion of wildflowers covering a spectrum of rich colors and textures, creating the most amazing fragrance floating along the calm, summer breeze. The happiest, little mountain stream babbled and splashed its way down from the upper lake through the meadow and came to pause in a very small pond where the water was so clear it had vanished. The colorful rocks and stones that bedded the bottom of the pond, perhaps 30 feet below, appeared to be dry, sitting in a depression in the ground, absent of any water but, because of the water, every stone shimmered with brilliant color. Dropping our packs, we sat down on a rock by the water’s edge, completely mesmerized by this optical illusion. I’m not sure how long we sat there but it was long enough for Craig to fish-out, fire-up and pass over the red-dot roach he’d been hanging on to. Eventually we got around to re-saddling the luggage and wandering further up this enchanted little, alpestrine valley. At the head of the valley, a boulderfield of bleached white stone rose up for several hundred yards. At the crest of these ashen boulders, as my sight cleared the last rock obscuring my view, Timberline Lake magically appeared. I had no doubt Berry Lake had been a spectacular spot but, thanks to the red-dot, this scene before me now was practically hallucinogenic in its electrically sharp and graphic beauty. We wandered over to the lakeshore and dropped our packs in the bleached gravel. The sky was infinitely blue, deep as outer space, with warm sunshine sparkling across the aqua blue lake. I happily sat down on my pack, munching a granola bar when suddenly KABOOM!

We dug into our packs and pulled out what was left of our Ray-Charles’ quickie-mart snacks and just baked out in the sun all afternoon. I tried to mentally imprint the fantastical scene all around me as there was no way a picture, or even a thousand, was going to capture the contrast, deep colors or complexity of what my eyes were perceiving. Well, our impromptu day-off may have been costly because when we rolled out the next morning the sky was pea soup. Our day called for a long, steep, talus climb to attain the ridge, followed by almost two miles of semi-technical ridgeline traverse along the Divide and this weather was not at all welcome. The misting clouds hung low and the wet lichen growing across the rocks was now slime-slick, making the entire talus field we were about to climb significantly more treacherous. We would have called a weather delay and waited for dryer conditions but we had already spent that time lolly-gagging about the lake yesterday instead of getting the ridge traverse behind us. There were no words exchanged between us before, during or after breakfast as we shuffled about, muted by the foggy, eerie scene that loomed above. Neither one of us wanted to climb up that slicked-over talus slope but at this point we were low on provisions and big on motivation; we only had two days left to complete this section if we didn’t get stalled-out by the weather. Finally, reluctantly, we decided to go up and have a look; if the conditions were too hazardous then we’d just come back down and wait it out. But then again, probably not.

July 20-21 Bitterroot Range, MT (Go to Pt 1) Once I regained my balance, I turned around to watch a gaping hole appear that was gobbling up barrel sized rocks all around it. Within minutes, rocks were disappearing into a void that had grown to 6 ft. in diameter and showed no signs of stopping. That’s when the danger hairs went up on the back of my neck. How big was this slope failure about to become? And how fast? That was something we did not want to find out and with all the swiftness that sudden panic brings we scrambled across the rest of the rock slope to the safety of the meadows beyond.

The air was sparkling after the rain and we sat out on the bank of the shimmering little lake that nestled up against a tall cirque where a large snowfield swept down the southeast face to lap the water’s edge. We were in high spirits that evening as we chatted over supper about the crazy events of the past few days. The hiking had been fantastic and all off trail. It was super-cool, really!

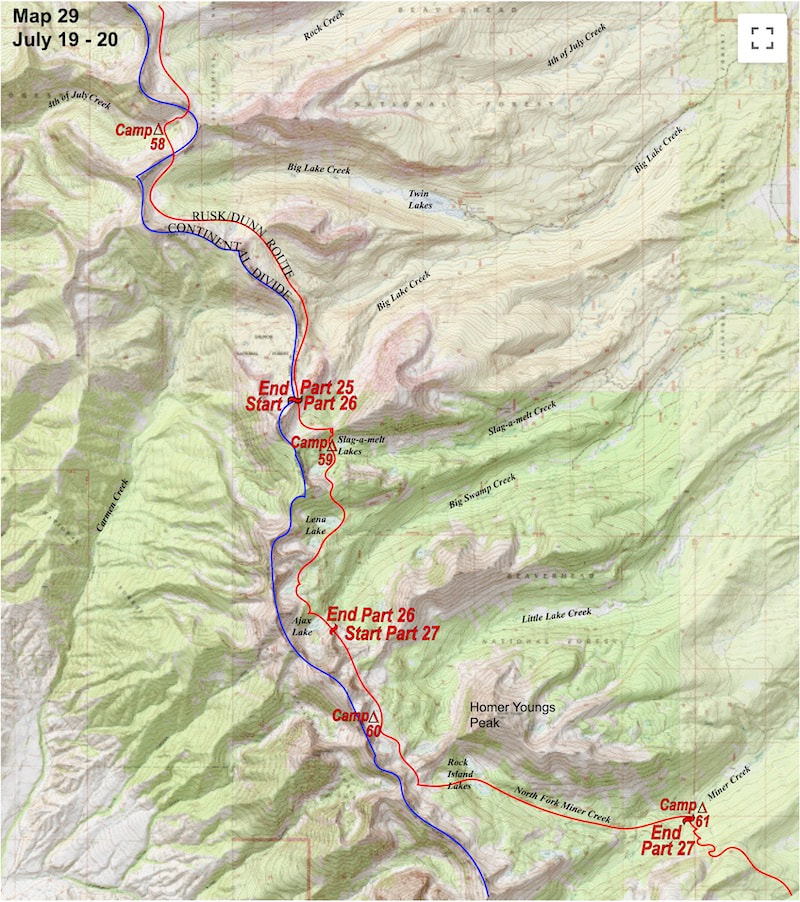

From the unnamed lake at the unnamed cirque we ambled about a mile across a beautiful, alpine plateau then climbed to the saddle of a ridge that connected the Continental Divide to Homer Young’s Peak. From here we would have to descend into the valley and eventually pick-up a trail that would lead us around a long, razorback ridge that blocked the path to our alpine route. We dropped to Rock Island Lakes and picked up a jeep track that led us down to Miner Creek. At Miner Creek we picked up a gravel road and started hiking up the valley. Shortly after starting up the road we spotted a maroon van pulled over at a view point. As we walked up to the van I didn’t know if there was anybody inside until the driver’s side door popped open and a portly, bearded fellow climbed out and offered up a cheery “Good Day” as we approached. We stopped and chatted for a bit and when he asked where we were hiking from I replied “Canada” and he about flipped out. He called to his buddy hanging out in the back of the van “Hey Ray, get out here and meet these guys, they just walked down here from fucking Canada, man.” Ray came out from the van with a big grin on his face and pumped our hands “No shit! You guys really walked down here from Canada? Shit-dang, I didn’t even know that was possible!” he exclaimed. They invited us to hang out with them in the van as they had many delicious food items to offer. Craig and I looked at each other and Craig was like, “Sure, why not?” And thus we got lured into the back of the van with promises of cookies and candy. Well, turns out they did have quite the assortment of cookies, crackers, various cheeses and chips, licorice sticks candy bars and loads of beer – I mean these guys had it all! (After we left neither one of us could remember the portly guy’s name so we started referring to him Charles.) While we devoured the goodies set out on the table in their decked out van and drank their cold beer, they went into a full-on interrogation about our trip and they wanted to know everything, from the equipment we were carrying to a basic lesson in orienteering. Finally, they got around to quizzing about what ‘civilized’ items we missed while we were out in the mountains. Food items were the first things we started to list but then Charles interrupted to say “I mean like items more in the ‘recreational’ department” as he raised his eyebrows to say ‘hint, hint’. “What, you mean like pot?” Craig finally asked. And Charles replied “Yeah, like pot. You guys want a toke?” We looked at each other and Craig was like “Sure, why not?” and Charles beamed from ear to ear as he pulled out a wooden box that held eight different strains of weed. “What kind of high are you boys interested in? Do you want to talk to the stars or are you more into a speedball ride?” Well, we figured something in the middle ought to be about right so Ray set about rolling up some joints while Charles took us through a botanical inventory of the various flowers in his box. Remember, this was in the mid-seventies in southern Idaho where a joint could send you to prison. In rural Idaho back then, drunk driving was tolerated where marijuana was strictly not. That right there made Charles’ collection of bud quite impressive indeed. We dithered away the afternoon laughing, munching goodies and hanging out with Ray and Charles. Before we left, Ray rolled up a few joints for us to take and Charles marked two with a red dot to let us know that those doobies were from his ‘trippy’ Columbian stash and to tread lightly. Besides the j-boys, R&C also loaded us up with plenty of good-eatin’, quickie-mart snacks and all the beer we wished to carry before we finally left their van late that afternoon. All in all, we didn’t get a darn thing accomplished that afternoon but we sure did have a good time. We camped a little further upstream at the base of a huge, unnamed mountain in a beautiful grove of cottonwood trees along the riverbank. After pitching the tent we went down to a deep, clear pool in the stream and smoked one of the red-dots. We sat on comfortable boulders alongside the pool until sunset, staring at all of the aquatic colors glittering up through the invisible water.

July 19 Bitterroot Range, MT (Go to Pt 1) The south side was angled such that all the larger, loose rocks had already fallen to the talus field at the bottom, leaving behind steep gullies of mostly gravel sized scree that was too steep to plunge-step down without losing traction and sliding off down the chute.

much as a second, cautionary thought I started to plunge step down the summit scree slope, angling toward the top of one of these chutes. Once I got positioned over the fall-line of the chute’, right where the real steepness began, I sat down in the scree and intentionally started myself sliding down the chute. Once I got going there was no way to stop other than riding it out to the bottom and, no matter how this turned out, I was going to end up at the bottom. As I plummeted down the chute I started a small-scale rock slide of mostly scree but, really, any sized rock that lay in my path and rocks exploded out of the chute, showering down onto the debris pile hundreds of feet below. As I was propelled downward I knew I could not let my boots heels dig into the scree to deeply or I’d get flipped into a cartwheel so I stabbed at the scree with the heels of my boots in a kind of slow motion flutter kick action that actually did help to slow me down some. It was all over in less than 30 seconds and when I, and the pile of rocks that came down with me, slid to a stop at the bottom of the chute in a massive cloud of dust I was stunned! I could not believe that had actually worked!

I let the dust settle then yelled over “Hey Craig! You OK?” He stood up and was completely covered with dust and dirt right down to his tear ducts, as was I. Normally, Craig would find this kind of high-stakes adventure disturbingly humorous with more wit directed at my ‘route finding’ or some other such profane exclamation but he was silent as he collected himself at the bottom. We climbed down off the debris pile then made our way across gentle terrain to a stream and dropped our packs to rinse off the dust. It was still fairly early in the afternoon and our scheduled campsite was not that far off so I started talking about pushing the route out a little further down the ridge to Lena Lake, which would require going over another valley-separating ridge. Craig sat on his pack, head bowed, clutching his right knee “No!” he finally interjected “I am not going over another ridge today!” I did not pick-up on this at the time but there it was, Craig’s right knee joint was beginning to break down but he said nothing of it at the time; only that he was done for the day.

Something was wrong but I didn’t know what it was. When I got back to camp Craig was going over the map, assessing the passes still out in front of us. There was scant conversation that evening and after the dinner chores were done I sat back to record the day’s events in my journal. We shut down camp around dusk and I went to bed that night kind of pissed. Was Craig starting to crap out on the trip? I didn’t know. The next morning I finally asked “What’s the deal, man? Is everything OK?” Craig was silent for a moment then said “Yeah, my right knee has been acting up lately but it’s done this before; it’ll go away.” And that was it. So I thought ‘Ok, I get that, an old injury acting up’ and dialed back the pace going into the day which started with a shallow pass followed by a steep descent to Lena Lake but one we could hike down. Craig was a little slow on the descent but at least now I knew why.

The cabin was sparse but comfortable with a picnic style bench and table, a made up cot in the corner under a small window and a few canned goods in the cupboard. We pulled our mid-morning snack of granola bars from the pack and lounged around the table, reading entries in a log book that sat there with the earliest notations dating back to 1956. After the morning break was over we circled around to the southeast end of the lake and climbed our way up to a scree and talus slope at the toe of a massive, unnamed mountain. As we were crossing the rock slope we nearly got swallowed-up in a sink hole. Craig was crossing ahead of me and was striding across the larger rocks when one of the rocks he stepped on wobbled in a very weird way; I was directly behind and stepped on the same 2 ft. x 2 ft. stone but when I got my weight over the rock it sank, like a stone you might say, about two feet. This threw me off balance as I lurched forward across several more wobbly rocks, stumbling to stay on my feet. Once I regained my balance, I turned around to watch a gaping hole appear that was gobbling up barrel sized rocks all around it. Within minutes, rocks were falling into a void 6 ft. in diameter, disappearing into the earth and showing no signs of stopping. That’s when the danger hairs went up on the back of my neck. How big was this slope failure about to become? And how fast? That was something we did not want to find out and with all the swiftness that sudden panic brings we scrambled across the rest of the rock slope to the safety of the meadows beyond.

July 18 - 19 Anaconda-Pintler Wilderness, MT (Go to Pt 1) Before we committed to the descent we dropped our packs and pulled out the lunch bag. We didn’t talk much about how we were going descend and after picking through our lunch ration for the day there was really nothing left to do but to start plunge-stepping down the steep scree to the splintered rocks below. The descent was sketchy but turned out to be not quite as steep or as long as coming up the north side had been. We bottomed out at the debris pile collecting at the base of the ridge then traversed back onto level ground.

but I just didn’t think my legs could carry me over another pass and Craig kept mentioning his knee joints at the bottom of each excruciating descent. We were done-in so we set about finding a tent site. The upper reaches of the valley were narrow and steeply sloped and despite being well practiced at searching out tent platforms it still took a while to find a spot that was not quite big enough nor exactly flat enough for the tent but, with a little ground-clearing and shoring, adequate enough to wedge in a camp. It rained on and off throughout the night and the next morning everything was wet; the trees dripped all over everything and once we got going the wet underbrush shed cold rainwater all down my bare legs. We wasted little time getting out of the brush and back in the sun to the base of a talus slope leading up to the next saddle we needed to cross. Here we were pleasantly surprised to find a wide, grassy meadow just beyond the talus that made easy work of reaching yet another pass along the Divide. From the saddle we traversed gentle terrain around a cirque formed by the Continental Divide at the head of the Big Lake Creek valley. We were walking mostly through thin, open forest interspersed with stretches of alpine meadow that reached out across about a mile and a half of gentle geography. The hiking was far away from any trail and it was absolutely fantastic! The terrain was a glide and my pack felt like it was carrying half the weight.

One option was to drop down several hundred feet in elevation and slog our way around the towering peninsula on trails (a plan I did not favor much) or we could commit to a half-mile bushwhack up-valley to climb over a steeply contoured spot on the ridge that we could not yet see. I was all for sticking with the route over the ridge but, for the first time since we started the trip in Canada, Craig balked at climbing over a ridge. He was looking at the steeply stacked contours on the map and shaking his head. I was like “What?” It was not like Craig to shy away from a direct route like this. “Why don’t you want to take the short cut?” I asked. We were still in the forest and did not have a view of the terrain, so this route planning was purely speculative based on what we saw on the map. “What if we get over there and it’s too steep to get up?” Craig asked “It’s a mile out of the way if we don’t get over it. And look at the backside” he stated, pointing at the steep, south-side contours. “Oh common!” came my tactful reply “We cross shit like this all the time!” Craig didn’t respond, he just handed the map back to me and shouldered his pack. “What?” I said, raising my voice. “Alright, let’s go” he replied, clearly irritated. ‘Well, okay’ I thought ‘the saddle it is then’ slinging my pack and marching off into the woods. We ambled across the long, sprawling pass through open forest until finally we got to where we could get a view of the ridge and our intended route over the saddle. Well, it did indeed look steep.

The grassy ramps had made quick work of the climb to the top of the ridge and I was about to give Craig the whole ‘I told you so’ attitude when we walked across the saddle and looked down the other side.

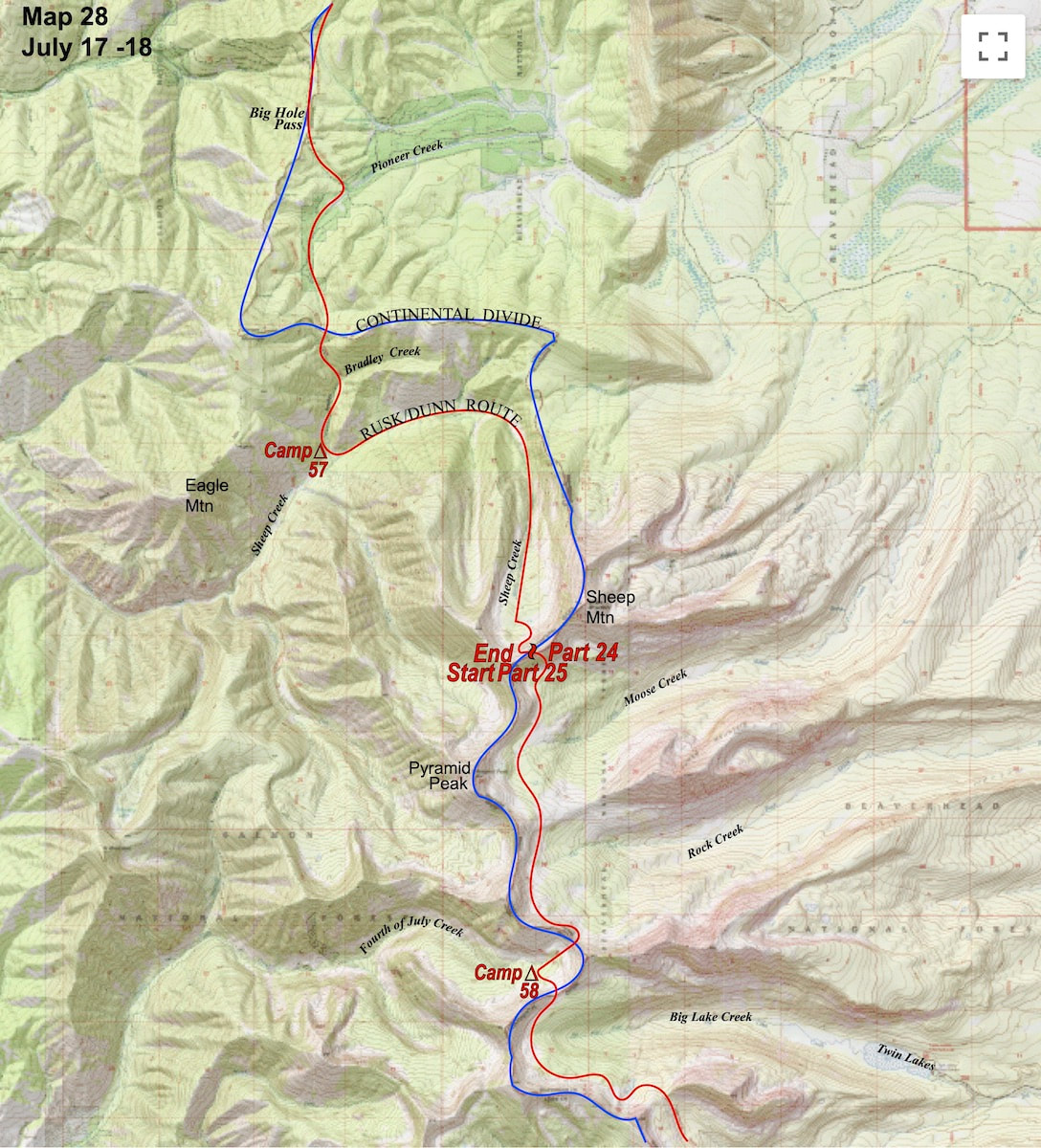

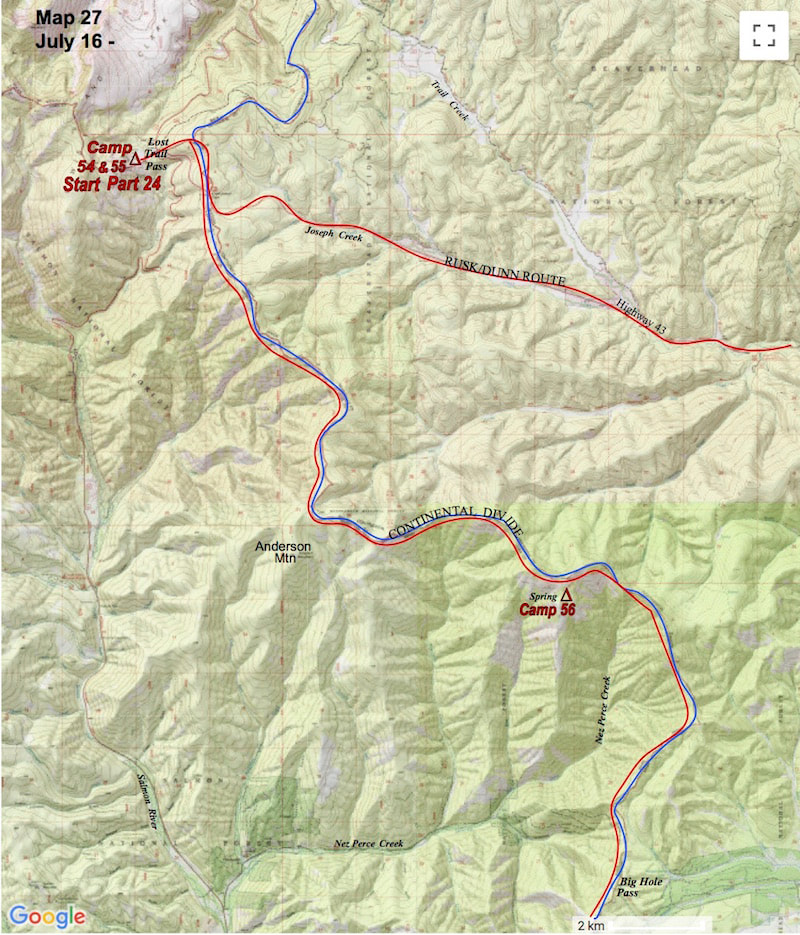

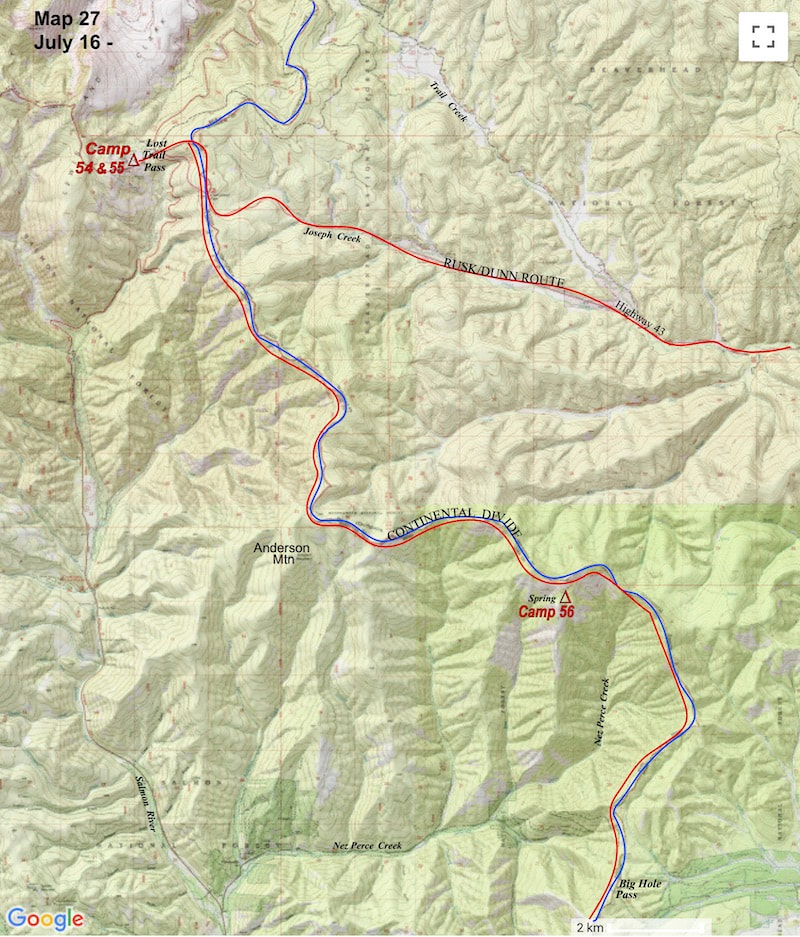

July 17 – 19 Salmon NF, Idaho (Go to Pt 1) Truck mufflers and slamming car doors at the Lost Trail Pass pullover rousted us out early the next morning. We rolled into our usual a.m. routine, packed up camp and hiked up a long, steep hill to rejoin the Continental Divide.

Finally, we climbed again in elevation and at the top of this rise the trees broke away into a vast, alpine meadow that emptied out to a staggering panorama of the southern Bitterroot Range. We stood and stared out over a hundred miles of southern Montana mountains, all of which we would eventually pass through.

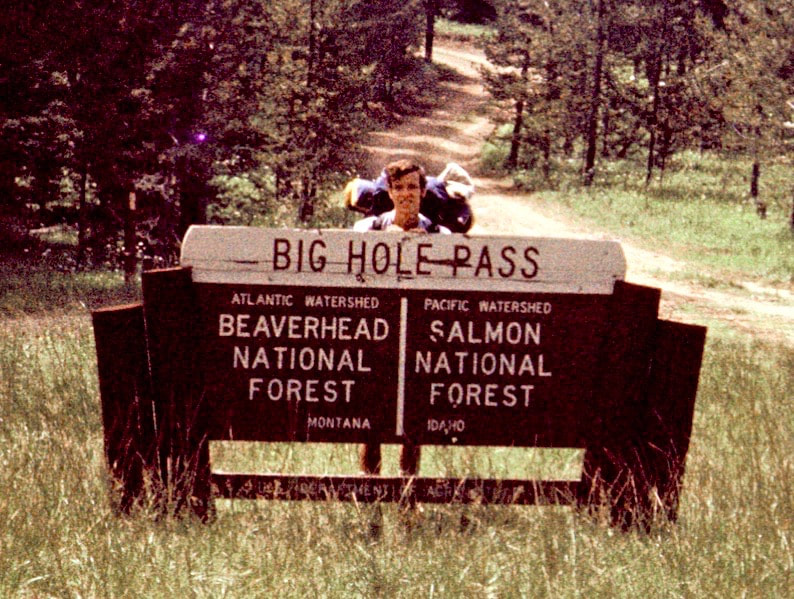

The next day we carried on along the ridgeline with our trail from the day before maintaining true to the ridge, circling the Nez Perce basin and bringing us out to Big Hole Pass by early afternoon. From Big Hole, the trail dropped into the Pioneer Creek Valley then climbed back up to a shallow saddle before again plunging steeply to Bradley Creek. We followed Bradley Creek down to Sheep Creek and set camp on a rocky hillside in a steep gorge because we were too spent to go any further. It was during supper that evening, as thunder rumbled off in the distance, that we debated whether or not a sudden and violent downpour of rain could possibly flash-flood our camp down river. After another, more thorough survey of our position relative to the river, we were both pretty convinced our camp was out of danger but then again, we had witnessed some fairly biblical rainstorms and the far off flashes of lightning had me a little on edge as I zipped into my sleeping bag for the night. Just as I had feared, rain moved in during the mid-night hours which then had me awake trying to calculate just how much water run-off in the gorge might be accumulating based on the pitter-patter on the tent fly and then I would listen to the sound of the river below our camp for any audible sounds of increased fluctuation. I lost a lot of sleep fretting in the dark about flash floods but by morning the sporadic nighttime rains had turned out to be nothing but wet.

We began traversing the talus up the ever steeping slope until finally, about 300 yards from the top of the ridge, the angle became so steep and the loose rocks so hazardous that we came to a halt. Teetering high on the loose rock slope we were a bit flummoxed as to what to do next, the traverse had become so precarious that it seemed foolhardy to continue that way but I was reluctant to give up the hard earned elevation we’d gained if we retreated back down the slope to look for another route. I looked up and the ridge-crest appeared tantalizingly close.

I ventured further up into gully, finding hand holds on the rock before advancing my feet, which skated out from under me several times, sending rock debris airborne before it careened its way off to the debris pile at the bottom of the face. Moving higher up, the trough continued to steepen and the climbing got exhausting, burning away at my calf muscles with almost no place to stop and rest. At the top, everything came to a head with the trough boxing out, leaving only steep rock to contend with. It was about 100 feet of forth-class climbing and with my load threatening to pull me off backwards every move had to be executed with forethought as to how the pack was going to affect my balance. All of the handholds and footholds were prominent and easy to reach and I got completely absorbed in the movement required to advance up the rock.

We walked the few paces there were across the top of the ridge and looked down the other side. Steep, shattered rock littered the cirque wall all down the south side face and it appeared to be a mirror image of what we had just come up, which was the last thing I wanted to see but it was either this or go back the way we’d just come. Before we committed to the descent we dropped our packs and pulled out the lunch bag. We didn’t talk much about how we were going descend and after picking through our lunch ration for the day there was really nothing left to do but to start plunge-stepping down the steep scree to the splintered rocks below.

July 11 – July 15 Salmon, ID (Go to Pt 1) From 1:00 a.m. to 3:00 a.m. it was a real cowboy show out there but somehow the tent survived and we stayed dry. From then on I knew that old tent could withstand a serious thrashing and be okay – as long as it got all of its stakes.

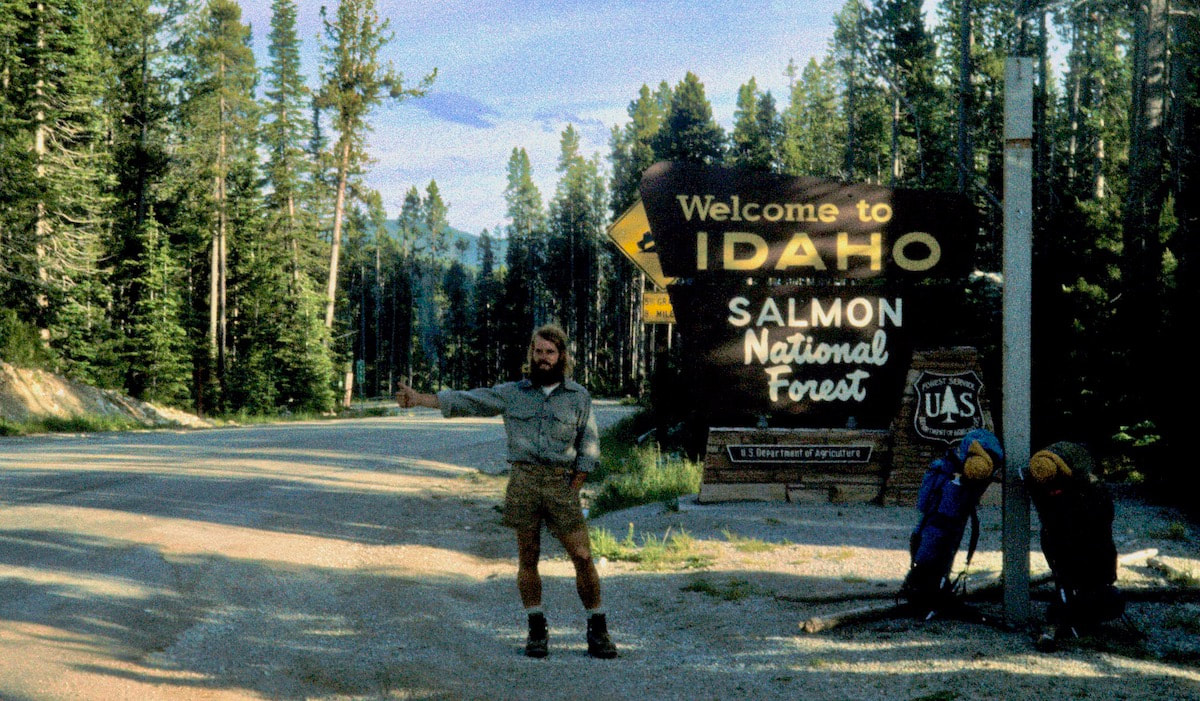

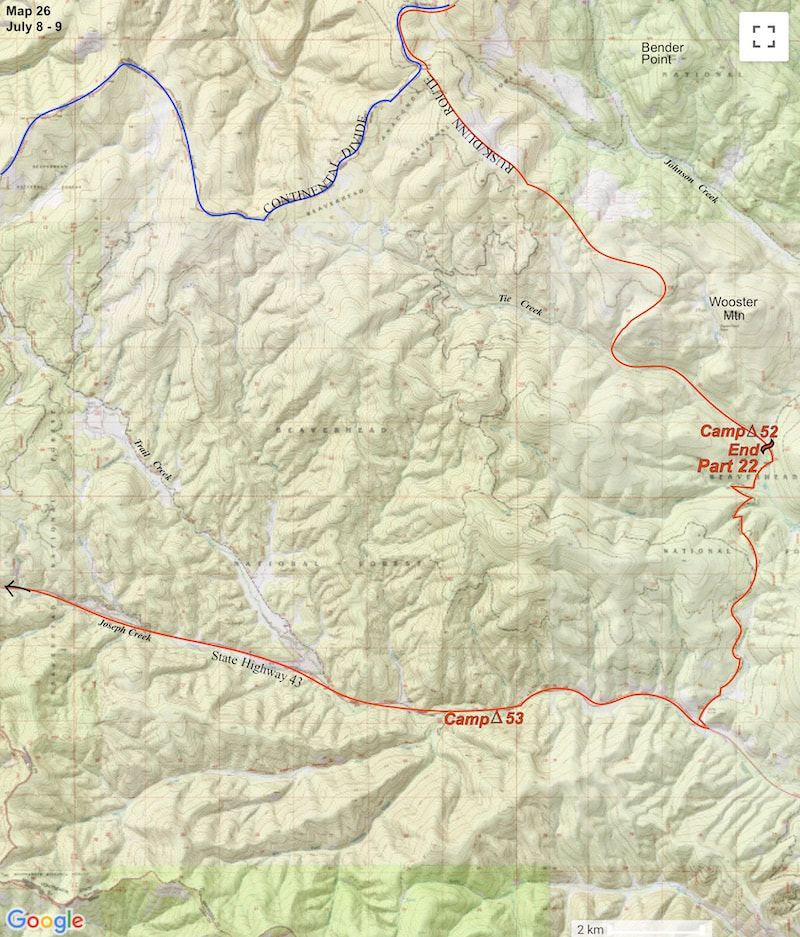

Following lunch we plugged a few miles up the road until I just stopped; I had no more desire to go further “Hey, Craig” I said “I gotta stop.” He turned and looked at me and simply nodded. We cut through the willows bordering the roadside and pitched the tent down along Joseph Creek. The next morning we continued on up the road hoping we could catch a ride to the top of the pass but the few vehicles that were on the road that morning were not in a ride sharing mood and we walked most of the way up before a couple of cowboys pulled over and gave us a ride the last few miles to the top. At Lost Trail Pass Highway 43 intersected with Highway 93 which was our road out to Salmon, Idaho. We made our final camp at Lost Trail Pass and the next morning we started the hitch-hike out to Salmon, arriving in town sometime mid-afternoon. The first thing we did after checking into the motel that afternoon was take a hot, soapy shower using a disinfectant , lice-soap we had picked-up at the drug store on our way in, then we shaved off our beards and went down to the local barber shop to get boot-camp haircuts. For the past week or so we had both been feeling creepy-crawlers on our scalp and in our hair and subsequently we had walked into Salmon with a pretty good crop of lice. The rest of that afternoon and all the next day we did absolutely nothing but hang-out at the café, making chit-chat with the waitresses which was fun having interactions with friendly, interesting humans not named Craig. We tried to watch a little news on TV while lounging between meals at the café and apparently Jimmy Carter, our newly elected President, was being interviewed in his new oval-office at the White House, but “news” just suddenly seemed alien to me, I mean, we were so out of touch with current events that the news made no sense – or maybe there just wasn’t all that much sense to be made out of it anyway. Well, when we strolled into the café for breakfast on our third morning in town and several of the locals at the counter nodded us a good morning, we realized we were starting to get just a little too comfortable here in Salmon. Over breakfast Craig mentioned that we’d better start getting our shit together and headed-on out of town before one of us started dating the waitress. Getting dropped off at the pass, I was having those now familiar feelings of anxiety and insecurity that came with venturing off into the unknown. Ambling down the hill from the highway, we dropped our packs at a level spot in the grass, sat down and stared out to the south along the ridge of the Divide. We sat silent for quite some time, as though the other person wasn’t even there. At that moment I was acutely aware that no one was making us come out here and do this other than ourselves and that rallying motivation was going to be, at times, one of the challenges we’d have to face. Finally, it was a couple of somber hombres that set about pitching the tent and putting together supper that evening.

July 9 - 10 Anaconda-Pintler Wilderness, MT (Go to Pt 1) Rain came down in sheets of near freezing water mixed with snow filled, hail-balls that exploded in puffs when they hit called graupel. We huddled up under our rain gear and watched the ground turn white with millions of exploding, graupel balls. After the worst of the onslaught had passed, we carried on along the ghost trail, which began to take some odd twists and turns.

location on the map, we just weren’t clever enough to map-and-compass our way out of here. So we really didn’t have much choice but to follow the high ground.

the valley, somewhat distant and far below, we could see pieces of a logging road snaking its way through the valley and now that we knew we were standing on a false ridge, we decided to descend into the valley and see if following that logging road would get us out to Highway 43. We had maybe a thousand feet to descend to reach the valley floor and as we began down the steep decline from the friendly, Sherwood Forest we had been hiking through, the thickly, wooded mountainside swiftly became a seriously hazardous bushwhack. The timber deadfall on this aspect of the mountain was stacked two to three feet high and the downpour we’d had earlier in the day had left everything slick under foot.

stuck up from the logs like giant, porcupine quills and this drop into the valley had quickly put us into some very dangerous territory. About 100 yards into this mess, I stood balanced on the top of one of these slick timbers and looked over at Craig who was about 20 yards off to my left. Craig was also trying to stick to a greasy log and he was looking directly back at me like ‘You gotta be out of your freaking mind!’ when suddenly he slipped - and just as he started to go down my foot shot out from underneath me and I fell pack/headfirst through the broken branches to the ground. I was stunned and lay still for a moment, then Craig yelled over and I yelled back “Okay” and struggled under the pack to stand-up again. We tried climbing up and over the log piles but with the packs that was utterly futile. Angling down and across the slope using the tree backs as ramps was the only to make progress. Three times I slipped and crashed into the steep deadfall and each time I was lucky enough to get back up with only a bruise or minor gouge but each time I went down I had to take a moment to be sure I hadn’t sustained a more serious injury somewhere because the anxiety of our situation was such that pain was pretty low on the register.

the flattest, tent spot we could find and rushed through another camp set-up to get away from the mosquito plague that had swarmed us upon reaching the valley. That night it rained harder than I had ever heard or seen rain come down before in my life and not just for a little bit, it was a biblical torrent for two hours non-stop. After a while, I became concerned that the sheer force of this continuous volume of water pounding down on the tent fly would start to rip away the seams.

The next morning we bashed our way out of the valley jungle up to the logging road and headed south down the muddy ruts.

|

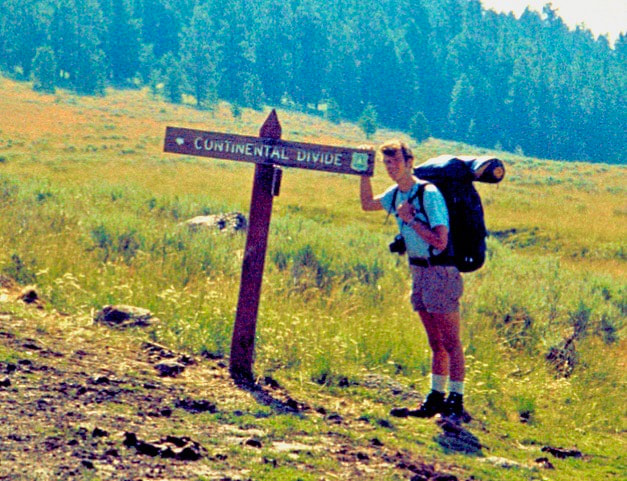

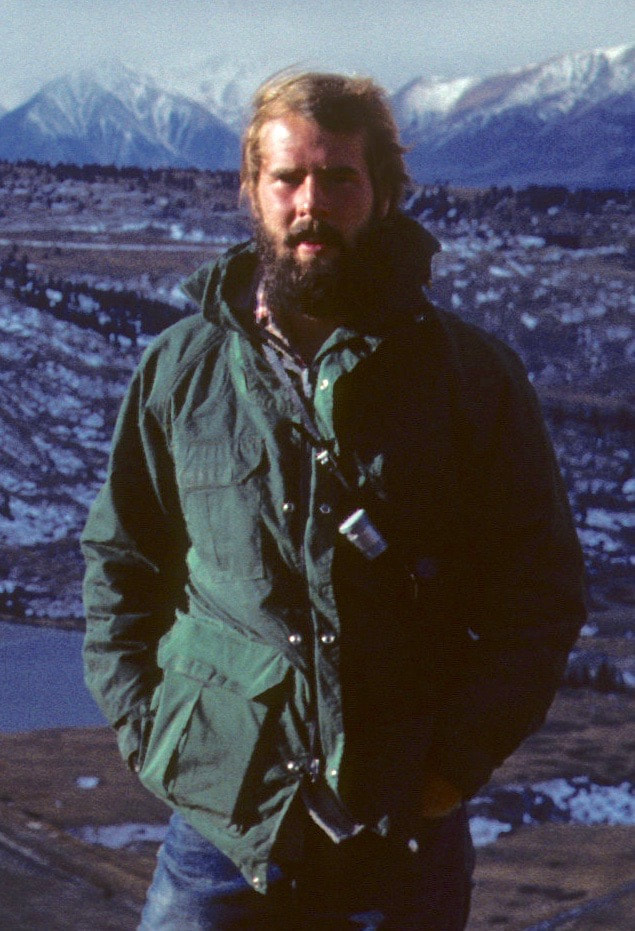

Kip RuskIn 1977, Kip Rusk walked a route along the Continental Divide from Canada to Mexico. His nine month journey is one of the first, documented traverses of the US Continental Divide. Montana Part 1 - Glacier Ntl Pk Part 2 - May 11 Part 3 - May 15 Part 4 - May 19 Part 5 - May 21 Part 6 - May 24 Part 7 - May 26 Part 8 - June 2 Part 9 - June 5 Part 10 - June 7 Part 11 - June 8 Part 12 - June 11 Part 13 - June 12 Part 14 - June 15 Part 15 - June 19 Part 16 - June 23 Part 17 - June 25 Part 18 - June 27 Part 19 - June 30 Part 20 - July 5-6 Part 21 - July 7-8 Part 22 - July 9-10 Part 23 - July 11-15 Part 24 - July 17-18 Part 25 - July 18-19 Part 26 - July 19 Part 27 - July 20-21 Part 28 - July 22-23 Part 29 - July 24-26 Part 30 - July 26-30 Part 31 - July 31-Aug 1 Part 32 - Aug 1-4 Part 33 - Aug 4-6 Part 34 - Aug 6 Part 35 - Aug 7-9 Part 36 - Aug 9-10 Part 37 - Aug 10-13 Wyoming Part 38 - Aug 14 Part 39 - Aug 15-16 Part 40 - Aug 16-18 Part 41 - Aug 19-21 Part 42 - Aug 20-22 Part 43 - Aug 23-25 Part 44 - Aug 26-28 Part 45 - Aug 28-29 Part 46 - Aug 29-31 Part 47 - Sept 1-3 Part 48 - Sept 4-5 Part 49 - Sept 5-6 Part 50 - Sept 6-7 Part 51 - Sept 8-10 Part 52 - Sept 11-13 Part 53 - Sept 13-16 Part 54 - Sept 17-19 Part 55 --Sept 19-21 Part 56 Sept 21-23 Part 57 - Sept 23-25 Part 58 - Sept 26-26 Colorado Part 59 - Sept 26 Part 60 - Sept 30-Oct 3 Part 61 - Oct 3 Part 62 - Oct 4-6 Part 63 - Oct 6-7 Part 64 - Oct 8-10 Part 65 - Oct 10-12 Part 66 - Oct 11-13 Part 67 - Oct 13-15 Part 68 - Oct 15-19 Part 69 - Oct 21-23 Part 70 - Oct 23-28 Part 71 - Oct 27-Nov 3 Part 72 - Nov 3-5 Part 73 - Nov 6-8 Part 74 - Nov 9-17 Part 75 - Nov 19-20 Part 76 - Nov 21-26 Part 77 - Nov 26-30 Part 78 - Dec 1-3 New Mexico Part 79 - Dec 3-7 Part 80 - Dec 8-11 Part 81 - Dec 12-14 Part 82 - Dec 14-22 Part 83 - Dec 23-28 Part 84 - Dec 28-31 Part 85 - Dec 31-Jan2 Part 86 - Jan 2-6 Part 87 - Jan 6-12 Part 88 - Jan 12-13 Part 89 - Jan 13-16 Part 90 - Jan 16-17 Part 91 - Jan 17 End |

© Copyright 2025 Barefoot Publications, All Rights Reserved