The Continental

|

That night was one of the eeriest nights of the entire trip. There was no moon and the dark was so impenetrable that it was impossible to look into the forest and not see something lurking in the trees. The silence was deafening but every so often I’d hear twigs snap and then rustling just beyond my sight. I got the crawling feeling that something was watching me, so I got up and walked around the perimeter of my camp, peering into the blackness. Craig flashed through my head because I was growing acutely aware of not having another strong, formidable, male human with mountain savvy at my side in the face of danger. And I was suddenly seeing danger everywhere I looked. It was well past dark and I should have been sound asleep inside the tent but instead I sat outside, wide awake, fretting about something prowling around just beyond my vision. I could feel it, I could sense it, but I couldn’t see it and I felt incredibly vulnerable. Later, and finally asleep in the tent, I dreamt that I was still awake and sitting outside the tent with all kinds of bizarre things going on in the forest that held me in a state of dread and fear.

On the east side of the ridge I found what I figured must be the trail shown on my map and followed it for several unidentifiable miles before it just quit somewhere in the woods on the northwest flank of Rabbit Ears Peak. From the inexplicable dead-end I had to work my way through a fairly dense forest until I was able to find my way down and around to the lower, eastern slopes. Here the forest opened up into large glades of aspen on easier terrain that allowed me to pick-up the pace, but not for long. Just as I was starting to stretch out my stride I began to hear crashing in the downhill woods below that I figured had to be either moose or elk because there was too much racket going on to be deer. That’s when I looked down through the trees and saw range cattle. “Fuck.” Range cattle were the worst. They were wild animals without a lick of sense. For instance, a moose, elk, or bear, won’t charge at you unless you give them a reason to do so, not so with range cattle. Range cattle are so blinded by instant panic that they’re just as likely to mow you over in an attempt to get away as they are to actually run away. As a result, their panicked reactions are a helter-skelter of unpredictable power. As I worked my way down the slope I became enmeshed with the heard but as long as I had trees to screen me I wasn’t causing too much trouble. Then, toward the bottom of the slope the trees thinned as the sagebrush valley opened up below and I lost my cover. By now I had numerous cows in a state of agitation, jolting hither and tither a few yards at a time and gathering in groups of panicked unpredictability. I crouched behind sagebrush bushes, allowing the senseless creatures a few minutes to forget they were upset and settle down, then I’d push forward another 20 to 25 yards, just enough to get the hags all riled-up again, before taking a knee behind some ridiculously scrawny bush that only a cow would see as a vanishing act. From where I was embedded in the heard, I still had about another half a mile to reach the fence line and I was completely surrounded. My movements now seemed to shock the cattle like a voltage prod and they were bolting into other cows, stirring-up a chain-reaction-disruption throughout the heard. If I wasn’t careful, I was going to have a small range-riot on my hands. I ‘hid’ behind a sagebrush bush and tried to focus on how I was going to get out of this pasture. Again, I thought about Craig. We had managed a lot of range cattle hiking through Montana and with the two of us we could employ strategies to move around the cows. In addition, the two of us together made for a more formidable looking creature to a cow. But out here alone, mimicking sagebrush was the only strategy I could come up with. I spent nearly an hour or more of slow, deliberate movement from bush to bush before I was able to reach the fence, practically snake-bellying my way out of the pasture. Man, was I relieved to get out of there! Overall, the dead-end trail, northside bushwhack, and range cattle episodes had cost me the afternoon with only an hour or so of daylight left to find a camp.

0 Comments

The next morning was cold, grey, and dreary and felt like a really good day to head into town. I only had a dozen or so miles to get down out of the mountains, so I was in no particular rush to roll out of my warm sleeping bag. As such, it was mid-morning by the time I set off from Summit Lake and when I finally did, I really wasn’t in the mood to hike.

They asked what I planned to do and I told them that I was at least going to continue on to Steamboat Springs, so I knew they would be anxious to hear from me as soon as I got out of the mountains. After getting my supply box from the Post Office, I sat down and gave them a call. Following the initial chit-chat, my Mom asked if I wasn’t getting tired and suggested that maybe I should consider taking a break and coming home. “You’ve made it so far,” she said “maybe now would be a good time to take a break. You know, you can always go back, and I just think maybe next summer would be a better time than trying… you know, trying to do it now, by yourself.” Then my Dad interjected, “We just feel that it might be best if you took a little time off right now. Even if it’s only for a couple of weeks. You have a lot to be proud of in getting as far as you have, and without Craig… and… you know what those Rocky Mountains can be like in the winter; we’re just concerned that maybe you’re taking on too much.” As they talked, I realized three things, in this order: The first was, I didn’t even want to think about going back home and facing all of my friends in the outdoor community with only half of the Divide completed. The second thing was the weather and the terrain; the good weather and moderate terrain provided no cover at all for justifying a bailout. And finally, unlike Craig, I was uninjured and healthy. In short, I had no credible excuse for abandoning the trip. I was listening to what my parents were saying but I just knew I couldn’t walk away from this endeavor now, and there would be no coming back at some later date. I finally answered their query and said, “If I stop now, either work or school or both will get in the way of me ever getting back out here, and… well, I think I should keep going while I can.” Of course, it never occurred to me that I was worrying my parents out of their wits with this little stunt of mine. Many years later my Mom confided to me the deep level of chronic worry she’d endured during the entire enterprise, but especially when I decided to keep going on alone. As for my Dad, I think he could understand where I was coming from, at least from the ‘now or never’ viewpoint, and he didn’t press the issue further, simply advising caution and saying if winter set-in, I should consider coming home. My Mom had little more to say. After I’d hung-up the phone, I felt satisfied and committed to my decision but unaware that my parent’s seed of retreat had been planted. Next, I dug through my resupply box which contained winter clothes, my winter sleeping bag and, among other things, a new pair of boots. I needed the boots but did not look forward to the break-in. Back then, mountain boots were constructed from thick, heavy leather and had unusually stiff soles for mountaineering. With boots like these, I really wouldn’t know what I had until I was back-up in the mountains, and hopefully not by the side of the trail bandaging blisters. I tried on the boots and walked around the motel room and the fit was okay, there was room for my toes and little slippage in the heels, but they felt like walking in a pair of cinder blocks. I looked hard at those boots and wondered how much of a fight they were going to give me before they gave-in. Straight out of the box they appeared to be a formidable opponent. The other note on my list was to pick-up a book while I was in town. For five months I’d been buying throw-away novels at rural, western grocery stores but in Steamboat I actually found a small book store with a selection to choose from. I figured I’d better get at least a couple of books to send ahead so I didn’t get stranded bookless again. That’s when I ran across Tolkien’s “Lord of the Rings”, three fat volumes that would last for months. I didn’t know if ‘fantasy’ was my genre or not but I had read the Hobbit in middle school and liked it, so I figured ‘what the hell’ and bought them. In hindsight, I wish I’d bought something else – reading Lord of the Rings while walking the Continental Divide turned into a psycho-drama all its own. Also, while I was in Steamboat, a friend of mine had given me the name and number of a friend of his, Jeff, that lived in the area and told me to call him when I got to town, so I rang him up. Jeff had heard that I was walking the Continental Divide, so when I talked to him on the phone he was excited to have me come out and stay at his cabin on the Elk River, which I did. I was intending to just stay overnight but once Jeff and his friends found out it was my birthday, or close enough, they hauled me back into town to some dark, downstairs bar decorated like an ‘Enchantment Under the Sea’ prom, and introduced me to a bottle of brandy. Of course, this was all riotous fun for the first couple of hours but as the evening wore-on I began to fade. I was used to going to bed around dark, so by 11:00 pm, and I don’t know how many shots of brandy, I was twice baked-over, toast. Back at the cabin I stumbled getting out of the truck, blacked out, and somehow woke-up in a bed the next morning. But, boy, did I pay for trying to hang with people possessing advanced degrees in partying. I sheepishly stayed over another night because I was too hung-over to get out of bed that day. Following my hangover day, Jeff drove me out to the Fish Creek Falls trail just east of town. As we were driving out there, and being an outdoors guy himself, he started asking me about my equipment, if my stove was working okay, “Yep, stove’s working great”, if I liked my pack, “Yeah, it’s riding pretty good”, and if I had a good tent. “A good tent?” I flashed on the old Gerry Year Around tent with its 17 stakes, seams stretched beyond the limit, poles bent with no shock-cord, a thousand pin holes in the floor, and to his question replied, “Nah, the tent’s pretty beat, I’ll probably have to get a new one.” “Huh, what kind of tent would work out there on the Divide?” he asked. “I don’t know,” I said, “something smaller, you know, lighter weight, more of a one-man tent.” Shortly afterwards, we arrived at the trailhead parking lot. Before letting me off, Jeff wanted to confirm that I would be in Georgetown for my next resupply stop. “That’s my plan,” I said, “provided I get that far.” “Best of luck, man,” Jeff offered with a big handshake, “drop us a postcard when you get to Georgetown and, seriously, be careful, it’s hunting season out there, you know.” I liked Jeff; he was a nice guy. I started from the trailhead under a crisp, autumn-blue sky, and hiked the twelve or so miles back up to the Continental Divide. Near the top of the Divide I came out to the Fish Creek Reservoir and considered making camp but decided to push-on a little further to Round Lake, which turned out to be a shallow, dark patch of water in a thicket of haggish-looking, fir trees.

Sitting serenely atop the bluff, absorbing the grandeur of the glowing landscape below, it suddenly occurred to me that it was September 26th. Or was it the 25th? No, I ran the days through my head and it was definitely the 26th. Well howdy-doody, it was my fuckin’ birthday! I was 22 years old.

Naturally, I had to climb over the gate and, fortunately, as I continued along the jeep trail I was able to stay in the forest, well east of the ranch buildings and primary road into the compound. Unfortunately, about a mile or so beyond the buildings, the jeep track I was following deserted me and turned east up a side valley. I stopped and reviewed my map which showed the main, access road into the ranch turning into Forest Service road several miles further to the south, so I struck out cross-country, angling south and west for the primary, access road. When I finally did come out onto the road, I wasn’t exactly sure if I was still on ranch property or if I had already crossed over into the National Forest, but I was pretty sure I was still on ranch property. I walked the road south for another half hour or so, through lit-up aspens, then across a brushy meadow to a clearwater stream where I stopped, it was around 5:30 in the afternoon. Ranch property or no, I was done for the day and pitched my tent. I emptied my pack, fluffed out my sleeping bag, then got water from the stream and was just about to light the stove for some soup when a truck appeared on the road just beyond and came to a slow, rolling stop about 50 yards away. ‘Ah, shit.’ A weathered man got out of the truck, walked over to my camp, took a look around, and with feigned curiosity in his voice asked, “What are you doing?” “Just camping for the night” I replied. “Well, you can’t camp here. You ain’t huntin’ are you?” He asked. “No.” I replied. Then I asked, “How far to the Forest boundary?” To this, the guy sort-of snorted and said “See that bend in the road down there? It’s just past that. But you can’t camp here.” “Mmm… yeah, okay.” Without saying anything more, the guy just stood there and watched as I stuffed away my sleeping bag, took down the tent, loaded everything back into my pack and started off down the road. A few minutes later I rounded the bend he had pointed out and sure enough, there was the locked, steel gate protecting the south entrance to the ranch. Dang-it, I’d set-up my camp within spitting distance of the property line. By now it was dusky with the clock quickly ticking down to dark when I found another tent site not too far beyond the gate and had my little camp back-up and running in short order. The ranch had the water locked-up on the other side of the gate, so it was a really good thing I had filled my water bottles at their stream before getting thrown off the property. The next morning brought clouds and a chilly wind that was about to blow many of the aspens clean of their leaves. I continued down the Forest Service road, eventually reaching a few scattered cabins called Columbine, then past Hahns Peak and down to Steamboat Lake. Down at the lake, I was more exposed to a wind that was right in my face, making the further trudge down to Pearl Lake take forever. After an eternity, I eventually made it to the lake where hunters with campers and RV’s were parked at nearly all of the available campsites. Luckily, I was able to find a good camp on the far side of the lake beyond the motorized sites. Looking over my map the next morning, I could see where I wanted to go, but aside from a circuitous, round-about route on the main road to a forest service road, there was no trail or woodland jeep track that would take me from Pearl Lake to the Zirkel Wilderness Area trailhead I needed to link-up with. If I stuck with the road down to Clark, I’d then have to double back on a Forest Service road to reach the trailhead I needed, and that was going to add another six or seven miles to my day, so I decided to go cross-country through the forest, around the base of Farwell Mountain to Hole-in-the-Wall Canyon, relying on the canyon to take me out to where I needed to be. Navigating through the forest and finding the canyon turned out to be surprisingly easy, and the canyon led me down to the Elk River where I was able to pick-up a short piece of Forest Service road that then led me to the trailhead. From the trailhead sign, a well-used and maintained path climbed steadily up into a shallow valley then continued on up to a lake called Three Island, just a short ways below the Divide. The lake was scenic enough but it was too cold and windy to sit outside, so I lounged in the tent and cooked my meal in the vestibule.

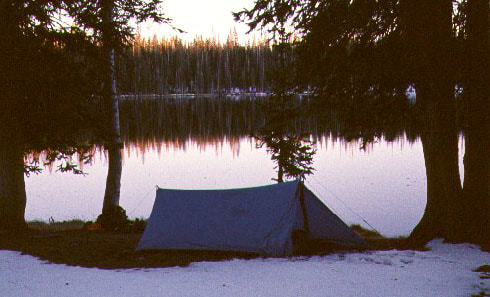

Once on the ridge, the clouds had me pretty well socked-in which obscured much of the surrounding landscape, but my pack was riding lite and the rolling, alpine terrain along the Divide made for relatively easy hiking. The clouds lying on the ridge were surreal at times, acting as visual, white noise that scrambled any sense of direction; I could have been walking circles without knowing it, and probably would have had it not been for the trail I was following. Around noon, though, the clouds lifted enough to reveal some pretty stunning views back to the north. I made it to Summit Lake at the top of Buffalo Pass toward the end of the day, arriving tired and hungry. I had expected to see hunters at the lake but there was no one else around. I staked out the tent then sat with my boots off for quite some time, hungry but lacking the motivation to go get water or light the stove.

Go to Part 60

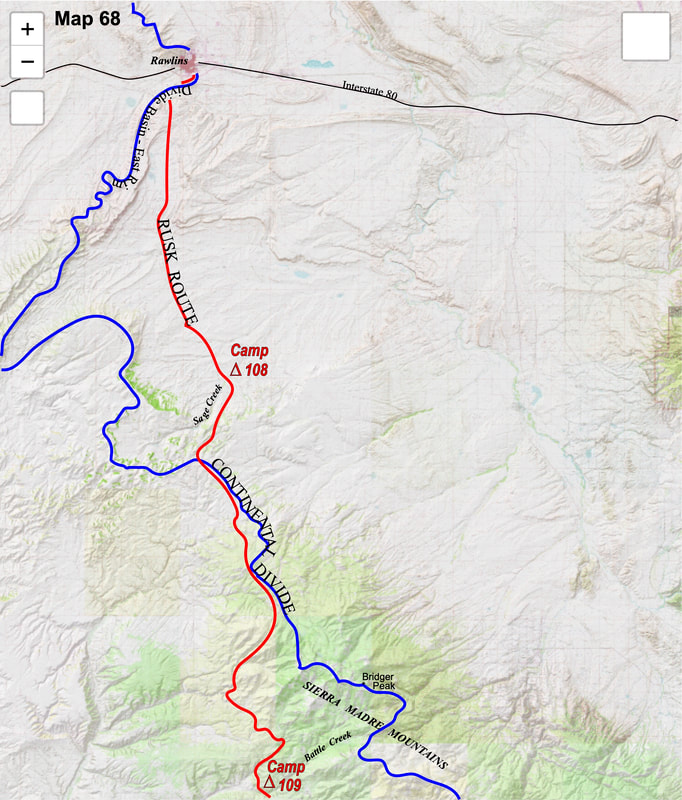

My moral and sense of wellbeing were not great walking out of Rawlins, but they weren’t terrible either. The endless hours of hiking had always been a one man game anyways, so, once I got going, the day was like any other mindless, road plod on hardpan gravel. The weather was totally benign, the landscape consisted of dried mud hills and the only wildlife to be seen were sheep, herds of domestic sheep. I made camp at Sage Creek with sheep grazing nearby (don’t ask about the water) and the forested hillsides of the Sierra Madre mountains just beyond. I fixed a one-man ration for supper then sat alone in the quiet emptiness until it was dark enough to get in the tent and go to bed. I was in desperate need of a good book, which I didn’t have, and made note to be sure and pick one up when I got to Steamboat.

I’d recently spent two nights in a motel and should have been well rested but after 5 months of hammering away at this Continental Divide ‘trail’, a low-level, chronic fatigue was settling in that made eating and sleeping really easy to do. By morning I’d spent nearly 16 hours in the tent, sleeping through most of it and stirring only to eat. The new day, however, beckoned as I clambered out of the tent into crisp temperatures under a cloudless sky. All at once I was anxious and excited to pack my gear and get going, I wasn’t far from crossing over into Colorado. As I headed out I could hardly believe how spectacular the day was with it’s deep-blue skies, autumn temperatures and flaming-gold aspen trees. Maintaining its southerly bearing toward the Colorado boarder, I continued along the leaf-covered jeep track I’d been following the day before.

Then something strange happened. Not long after my lunch stop I crossed over the Colorado/Wyoming boarder and it took me a couple of miles to notice, but I suddenly realized that I hadn’t seen a single deer since walking into Colorado. That seemed odd. I was wondering where they’d all gone when I heard a gunshot off in the distance, and not long after that another one, and then another one. Ah, it was early hunting season in Colorado and the deer were keen, they had crossed over into Wyoming where hunting season in the Medicine Bow National Forest had yet to start. I found it intriguing that the deer knew exactly where the boarder was and just how far they had to go to be safe. I continued on and by late afternoon the path had climbed out to the top of a bluff overlooking the Three Forks Ranch and the Little Snake River valley. The scene was striking and I dropped my pack to gawk at the landscape beyond. The sparkling waters below drifted through a wide expanse of golden meadows which were backdropped by the deep, forested green of the mountainsides. Spangled throughout the evergreens were clusters of iridescent yellow and orange aspen and the river bottom was embroidered with explosive, green-gold cottonwood trees. The late afternoon sun created a soft, golden light, illuminating the colors in a shimmering brilliance. Go to Part 59

September 23rd - 25th Rawlins, WY (Go to Pt 1) I reached Interstate 80 late in the afternoon with a cold, harsh wind blowing down the interstate corridor. Broken glass and cans littered the ditch alongside the highway and paper trash blew in the wind. Across the Interstate sat an old, weathered gas station/convenience store/Greyhound bus stop. I crossed the highway and entered the building, leaving my pack at the door.

It was still daylight when the guy let me off at an exit ramp on the west side of town. I walked down from the highway to the nearest motor lodge and got a room, checking to see if Craig was registered there, which he wasn’t. I went to my room and decided to wait until tomorrow to call around and look for him. I took a shower and ate supper at a diner across the street then sat in the darkening motel room, watching cars pass by on the roadway beyond. Sitting alone in the dark, Craig’s absence was keenly felt. We had been working together on this project to walk the Divide for well over a year now and had been dogging it out on the trail for over four months. The struggles we had endured and the terrain we had covered and survived had depended largely on the motivation and perseverance of two guys, and now that synergy was gone. Whether I had enough motivation and perseverance to fill the void I didn’t know, but before walking out of the desert I had decided I would at least complete the rest of Wyoming and continue on to Steamboat Springs, CO, which was the next planned section of the trip. For me, getting to Steamboat would mean something extra because in 1955 I was born in Steamboat Springs. If I wasn’t going all the way to Mexico then at least getting to Steamboat made sense to me. The next morning I called a couple of motels and found where Craig was lodged, which was just down the street from me, and rang him up to see where his plans stood. He told me that after he’d gotten out of the desert he’d called his parents back in Oregon who were now driving out from Portland to collect him but were still a day away from being in Rawlins. He also said he’d found the potholder and a couple of other doodads in his pack and would stop by my motel room in a bit, then we hung up. I wondered what I was going to say, ‘Tough break, pal. It’s been fun, good luck’? In one sense, it was a relief the measure had finally run its course but when I put myself in Craig’s position I could see how utterly devastated I would have felt had I suffered a similar, breakdown injury. And I’m sure I would have pushed things to the breaking point, same as Craig had, because admitting the injury meant defeat. But I didn’t dwell long on this part of the overall, gloomy situation at hand because I was too preoccupied with worry about myself. When Craig finally stopped by my room, he didn’t stay long. I asked him what he thought he might do next and all he knew for sure was that he was going back to Portland to look for work. Then I asked what he was going to do about his knees and he just shrugged. Without health insurance, which neither of us had, there wasn’t much he could do. Besides, knee surgery in the ‘70s wasn’t nearly the miracle it is today and didn’t offer a practical solution for most people. The conversation wore thin pretty quick; I was going to continue on, at least to Colorado, and Craig was headed back to Oregon. Beyond that, there was really nothing more to say. Craig’s disappointment and dejection lay heavy in the room and “sorry” was all I could manage. Craig left and that was the last time I saw him. The next morning I walked out of Rawlins, headed south for Colorado. Go to Part 58

I must have dozed-off because the next time I looked at my watch nearly an hour had passed, although it didn’t seem like I’d had been waiting that long. Now I was a bit alarmed and decided to walk back up the road to where I could see if Craig was coming or not. I had only just gotten up to start walking when Craig came limping around the distant mound and hobbled down the road to where I stood. He dropped his pack in the gravel and sagged to the ground clutching his right knee, “I can’t go any further” was all he said. The only surprise here was that he had made it this far. I stood silent for a moment then, as a point of logistics, stated the obvious “Okay, well, we’re going to have to get you out of here, then.” Craig sat on his pack with his head in his hands. “Yeah, I know” he replied. Then he looked up and off into the distance, resignation etched in his face, adding “I’ll just have to wait until a truck comes by.” I could count on three fingers the number of trucks that had passed us since leaving South Pass two days ago but that was the only way Craig was going to get out of the desert, now. “Yeah, okay… well, I guess I’m going to keep going then” I finally said. Craig sat staring off into nowhere and replied “Yeah, I’ve got some stuff you’ll need.” He got up and pulled a couple of communal items of gear from his pack which I transferred to mine.

We briefly explained our situation and the guy was happy to help but said he wasn’t driving all the way out to I-80. It was at least a move in the right direction, so Craig threw his pack in the back, climbed in the cab and the truck drove off.

This kind of irony was right in Craig’s wheelhouse and while neither one of us was in much of a joking mood, Craig couldn’t help but crack a smile as I processed this news, not because he was glad I’d fucked-up but because, face it, if it’s not you, it’s pretty damn funny. I had just walked down a single, solitary, dirt road with but one intersection along the way, a critical intersection, and I had walked right past it. A classic version of “He only had one job”. I was too far down this road to turn back now, so, fortunately, Craig gave me an extra quart of water he had which gave me just enough to get out of the desert. Because I’d missed the cutoff out to the water source I now had to navigate my way back across the open flats to go find that cutoff road because that was my route out to Wamsutter, a ramshackle outpost along Interstate 80. For the second time that day Craig and I parted, Craig remaining to wait for transport while I struck out across the open desert. By the time I finally spotted the errant road off in the distance it was late in the day and the sun close to setting. It was also around this time that I became aware of something following me. For some reason I suddenly had this crawly, weird feeling, so I turned around to look and was immediately alarmed to see three wild horses, two white and one black, about a hundred yards in my rear and following. Escaped, domestic horses, bred in the wilds of the desert. I had been told that wild horses were very smart, territorial, and known to be aggressive toward interlopers. John, the wildlife biologist we had stayed with, had warned us about these stallions, advising us to never engage the horses in any way and, in particular, avoid eye contact of any kind. “What if they get aggressive?” I’d asked. “Well” John had replied, “if the horses decide to kick the shit out of you, then you’re going to get the shit kicked out of you, simple as that.” I turned around and focused my eyes on the gravel road out in the distance with the stark realization that there wasn’t a darned thing I could do about these animals stalking me, so I just continued my pace and tried to pretend they weren’t there. I reached the road just after sunset with the horses still in my shadow and there was no more putting off the inevitable, I had to stop for the day. I had no idea what these wild horses would do when I stopped, maybe that’s when they’d kick the shit out of me, I didn’t know, but walking the remaining 25 miles out to the highway was not an option, my feet ached and I was exhausted. So, in a desert version of Russian Roulette, I finally dropped my pack and sat down. I sat still, just staring at the ground for several minutes then glanced behind me to see the three horses still standing there but now about twice as close as they had been. I slowly stood up and remained standing still, looking in the opposite direction of the horses for several more minutes then slowly, very slowly, set about unloading gear from my pack. The horses stood off in the short distance and watched. I was starting to feel a little more comfortable and decided to set-up the tent (for wind, not rain). The horses remained, watching me set-up the tent, cook supper and for the rest of the evening until I eventually climbed in the tent to go to sleep. The next morning when I woke up and looked about, the horses were gone. Outside the tent there was one pack and one pair of boots and the absences of Craig’s gear momentarily surprised me, then struck me pretty hard. It felt like the whole Continental Divide enterprise was spiraling out of control, and while I knew I’d make it out of the desert, beyond that had become a virtual unknown. I was more alone than I’d ever been in my life and more physically and psychology isolated than most can imagine. I started off down the road, headed for Wamsutter, and had walked about 45 minutes when over a rise off to the east the three ‘horsemen’ reappeared. My anxiety level increased a bit but nothing like the jolt I’d gotten when I had first noticed them following me the previous afternoon. We were familiar with each other by now. Like yesterday, I just kept my gaze forward, maintained a steady pace, and after a couple of hours I noticed the horses begin to trail off in the distance. I must have finally gotten beyond their territorial boundary because they had stopped following me but remained watching until I could no longer see them.

Go to Part 57

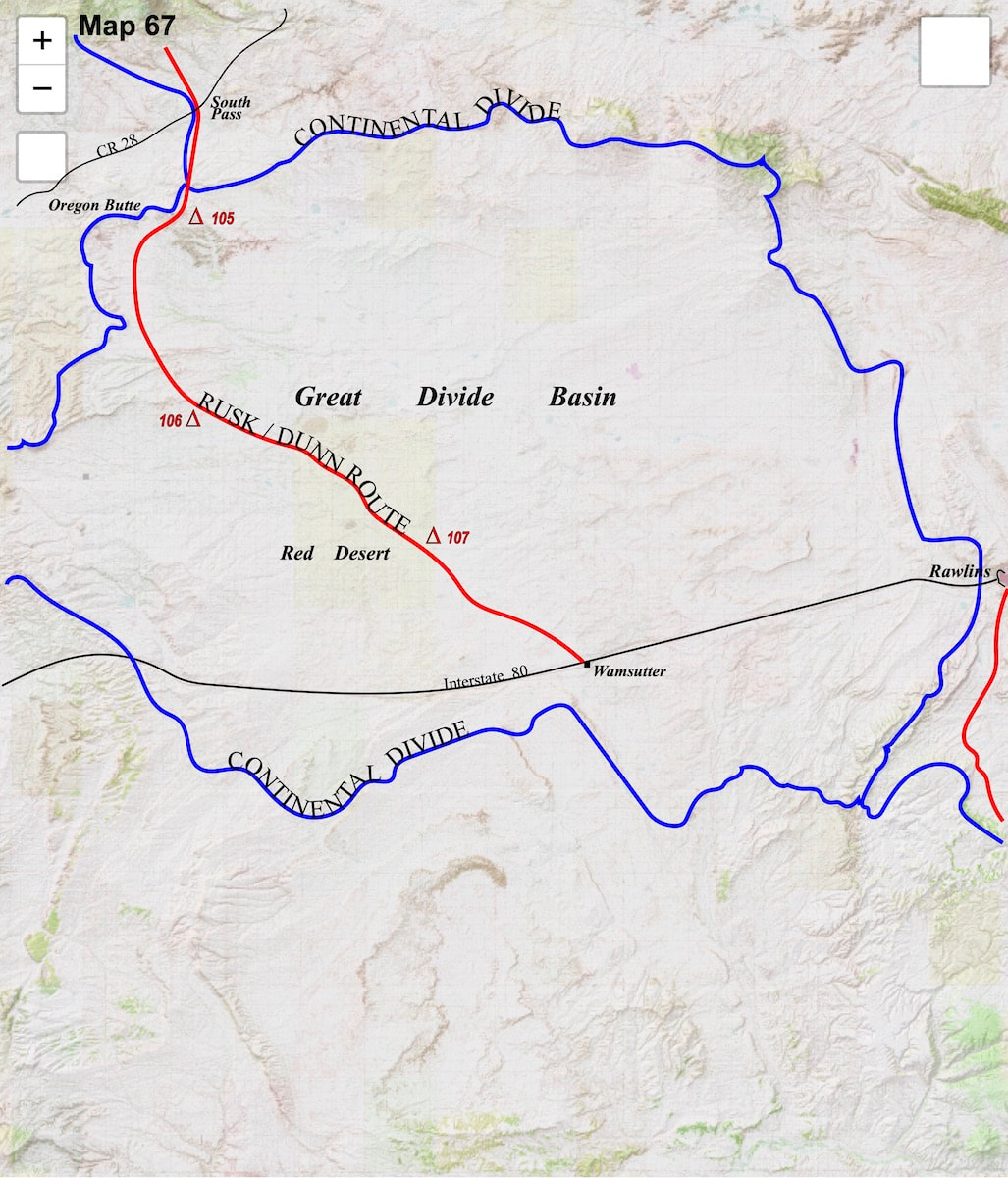

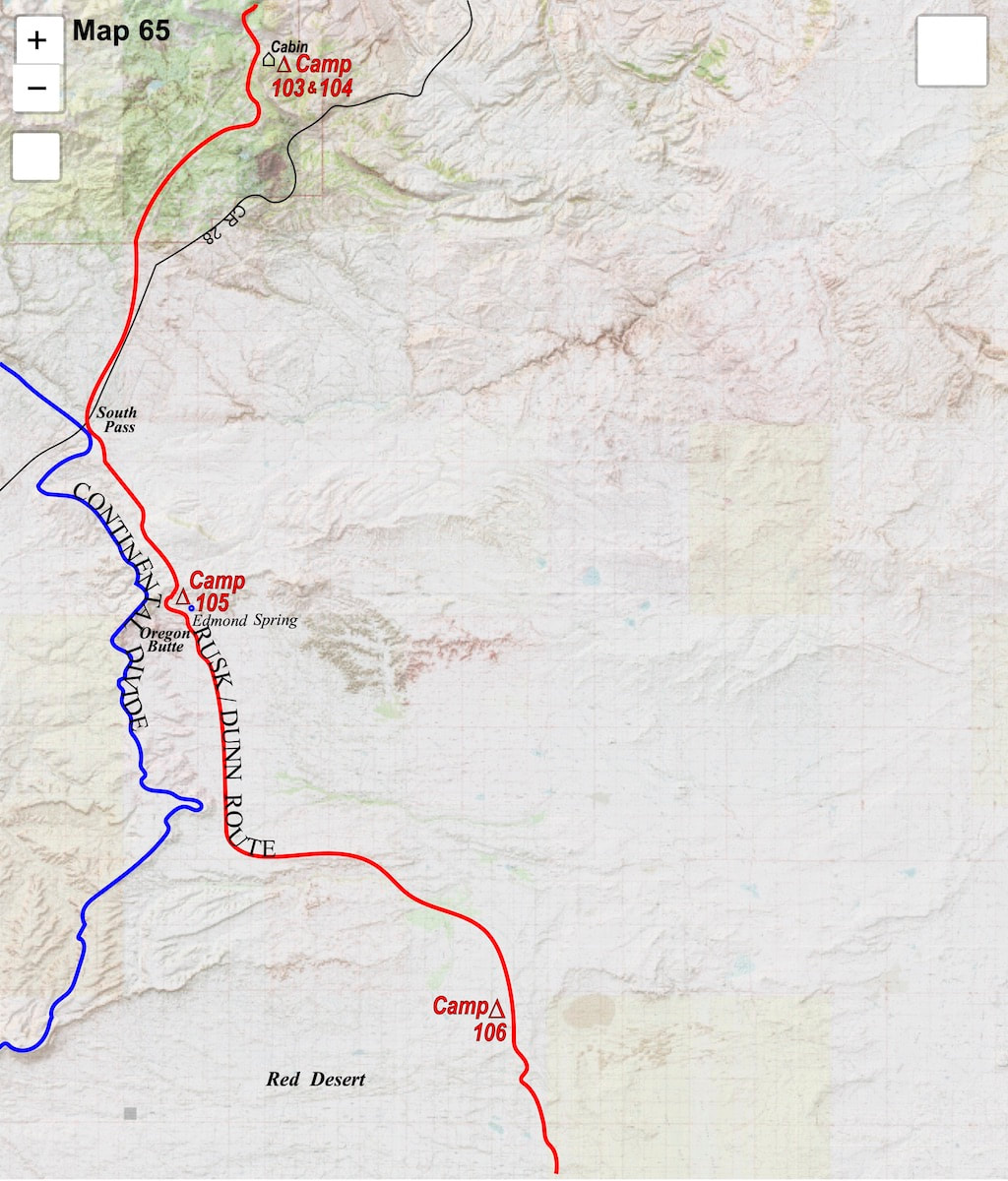

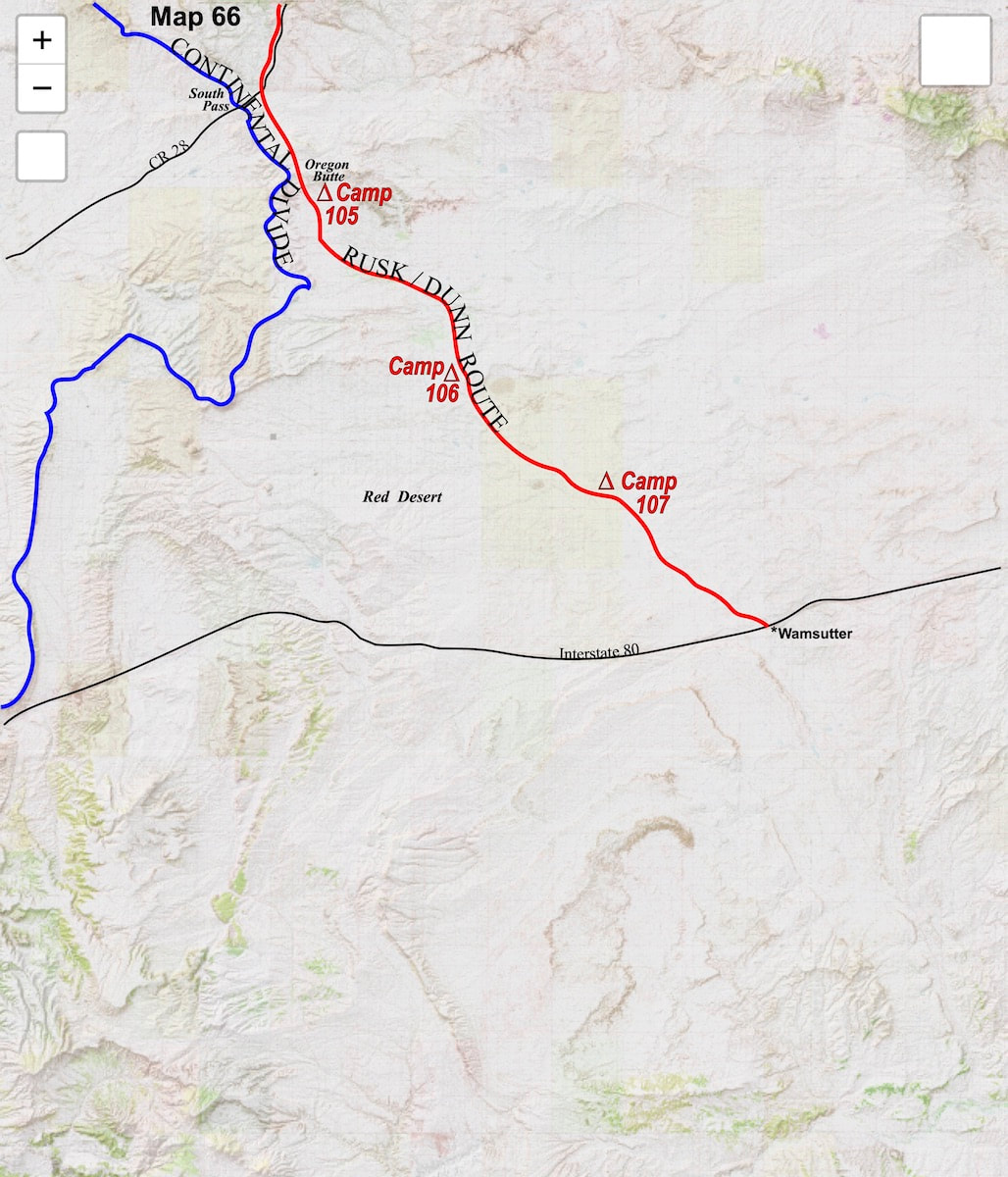

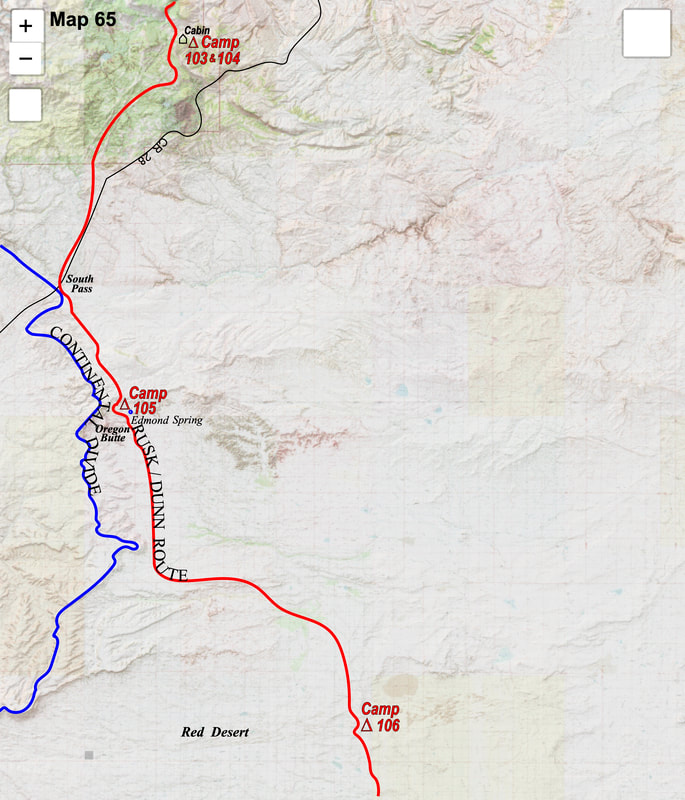

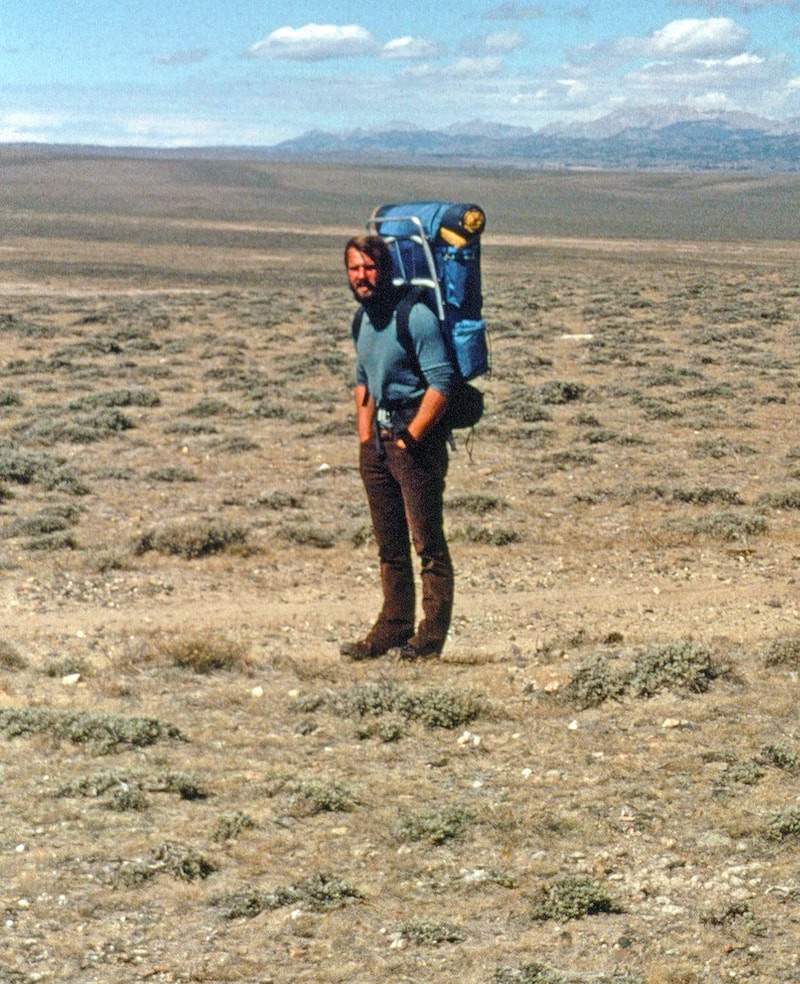

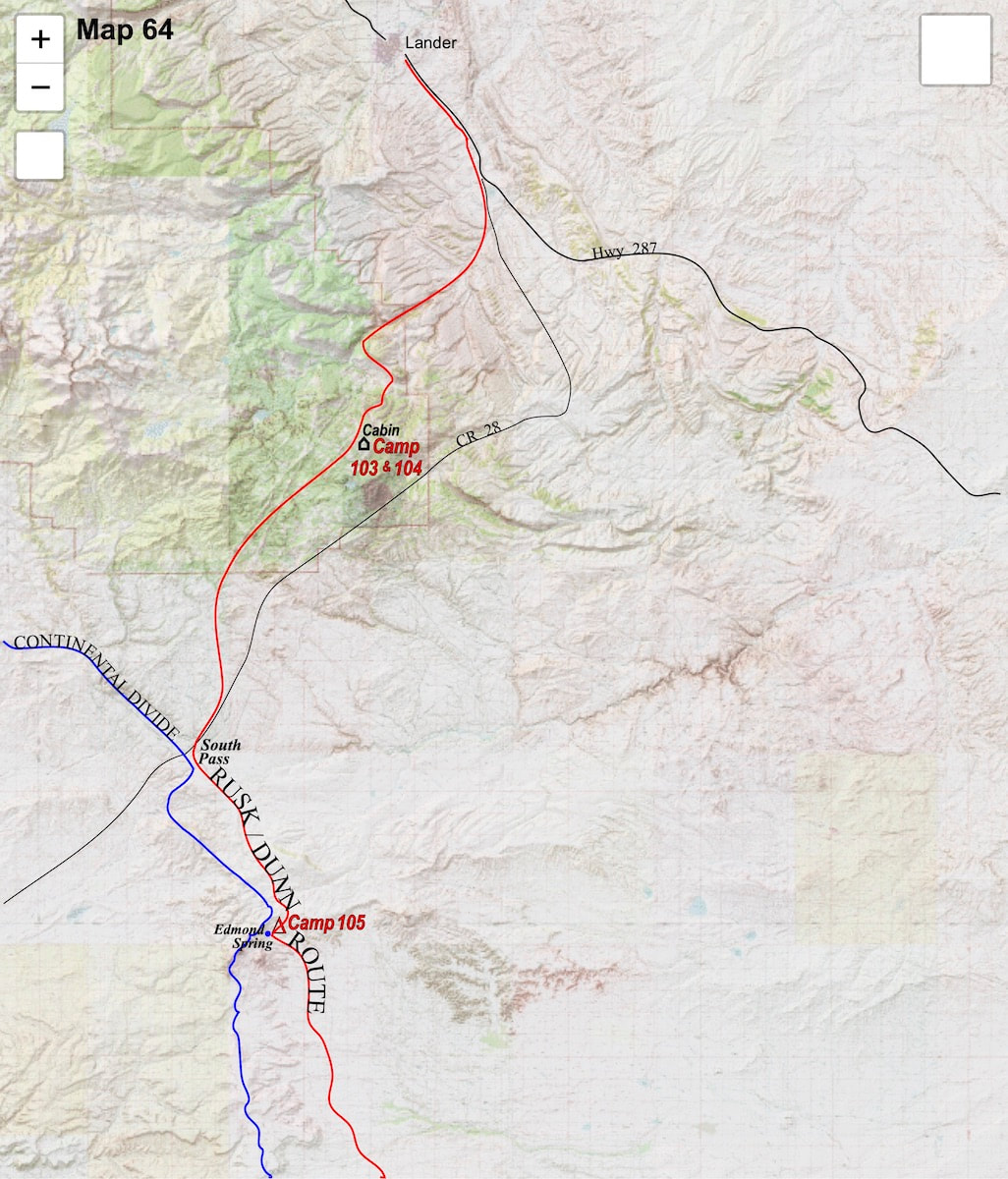

September 19th - 21st Great Divide Basin, WY (Go to Pt 1) The butte John had pointed out was so distant as to appear only as a wavy, mirage-like feature on the horizon and out ahead of us stretched a ruler-straight ribbon of gravel road that vanished off in the distance long before reaching the butte. Looking down that barren road, I felt like we were wandering out toward the edge of the earth; the desert marathon had begun. Although the gravel road we were on appeared flat it was actually pitched slightly toward the desert and, from the toe of the foothills, the grade continued to descend over the next fifty miles. This was full-throttle terrain for us except as I pushed to maintain a 4mph pace out to the butte, Craig had to back-off the near jogging tempo because it was too much of a jolt to his joints.

the sagebrush. When Craig finally joined me, I pointed out my sagebrush-shortcut route across the wasteland but the look of resignation on his face pretty much said ‘yeah, so,’ so I turned and started out through the stunted sage.

My apprehensions were growing, mountains I could figure out but this vast emptiness with but a single dot of water two days distant had me worried. And Craig had me worried; his determination to push out into the desert was a gamble, to say the least, and so far, things did not look promising. His gait was off with a slight limp to the right that could no longer be concealed. The following morning we loaded our packs which would have been wonderfully light were it not for the 2 gallons of water we were each carrying, water we would need to last us through the next two days. From Edmond Spring we made the long, gradual descent into the Red Desert.

As the day wore on, the walking distance between Craig and I grew further and further apart. Later in the afternoon, as I was starting to wear down, I stopped to give my achy feet a rest. Then, about an hour after that, I stopped again because my feet were really starting to ache, taking an extended break this time and even untying my boot laces. I looked back in the distance to where Craig was out there trying to catch-up, I hadn’t seen him stopped even once during this protracted afternoon. After 30 plus miles and with the sun beginning to dip toward the horizon I decided it was finally time to stop. There was still daylight enough to go another 3 or more miles but my feet ached so bad from the relentless road pounding that I didn’t think they could take any more miles. I dropped my pack, sat down and pulled off my boots, ahhh… Then I looked back up the road, scanning then straining to see Craig who was at least a mile away. I just shook my head in deference, realizing that no matter how much my feet hurt, Craig’s misery had to be twice as bad.

There wasn’t much of a moon that night and the stars were about as dense and brilliant and dazzling as I’d ever seen.

I must have dozed-off because the next time I looked at my watch nearly an hour had passed, although it didn’t seem like I’d had been waiting that long. Now I was a bit alarmed and decided to walk back up the road to where I could see if Craig was coming or not. I had only just gotten up to start walking when Craig came limping around the rocky outcrop beyond and hobbled down to where I stood. He dropped his pack in the gravel and sagged to the ground clutching his right knee, “I can’t go any further.” The only surprise here was that he had made it this far. Go to Part 56

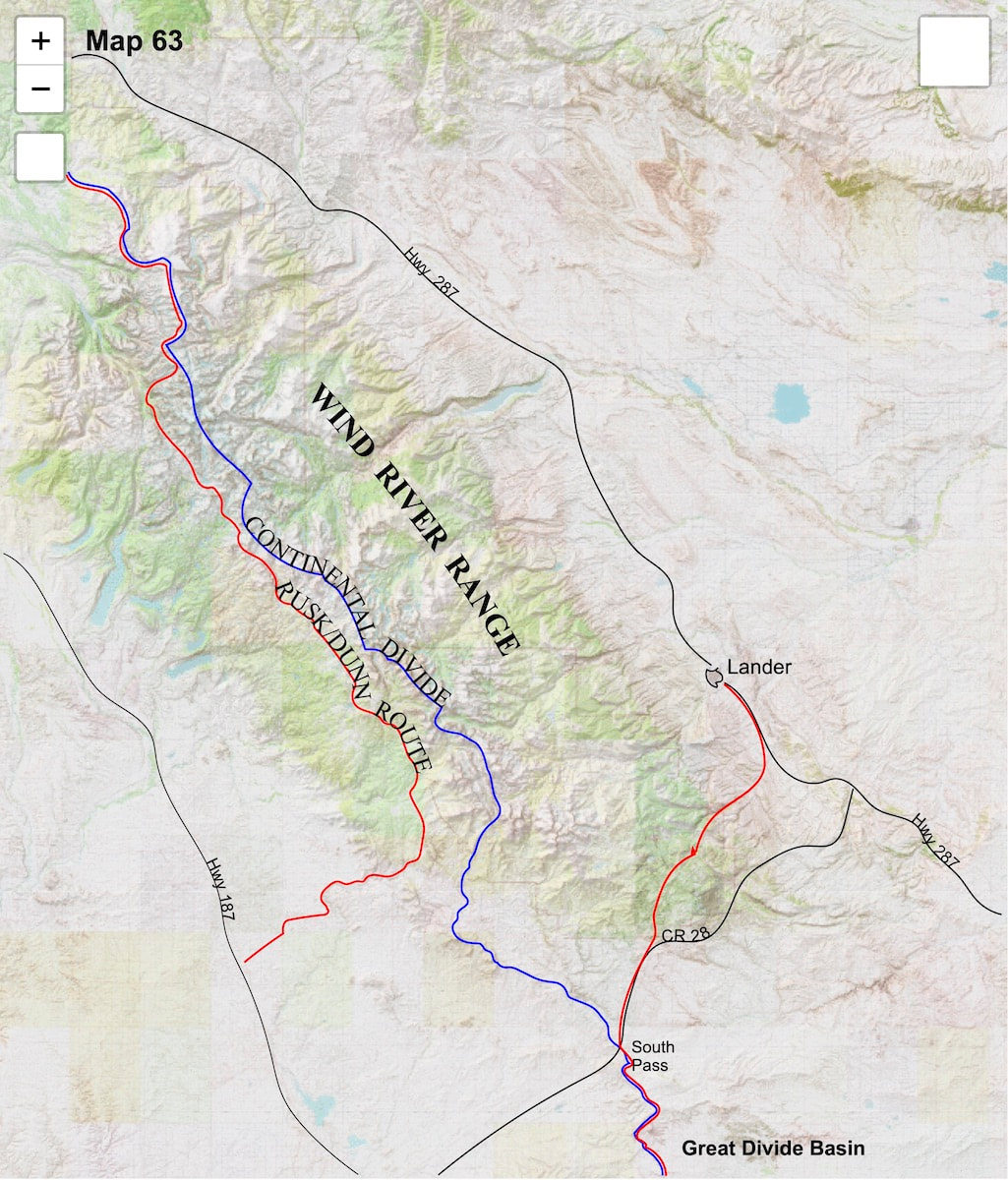

September 17th - 19th Great Divide Basin, WY (Go to Pt 1) We walked out of Lander the following morning, first on pavement then out onto a gravel road. We followed the road down to the Little Popo Agie river where we began to work our way up into the meandering foothills on unimproved, dirt roads that seemed to run all over the place.

I stepped over to the truck and replied “Actually, we’re just looking for a place to camp tonight. Do you know, is there any water close-by?” The guy, who looked friendly enough, smiled and said, “Yeah, hop-in, I live just up the road and you can camp at my place, I’ve got water.” I paused to look over at Craig then back at the guy who again said “Hop-in, I’m just up the road.” So, we threw our packs in the back of the pick-up and hopped-in. The driver introduced himself as John and after getting our names he wanted to know just what we were doing up in these woods, in as much as we were the first ‘backpackers’ he’d come across in the eight or so years he’d been living up there. “Well,” I replied, “we’re trying to walk the Continental Divide from Canada to Mexico, so we’re on our way down to the Divide Basin now.” Upon hearing this, John became engaged like we were already good friends saying, “You guys have to come up to my place and tell me more about this trip you’re doing!”

John was a laidback, easygoing kind of guy who quickly became a fascinating character as he told us more about himself, a published and nationally recognized wildlife biologist who had chipped away at building his homestead here in the woods over several years using only hand tools, many of which he had made himself. But initially, he was interested in quizzing us about our Continental Divide trip and asked a litany of questions about the flora and fauna we had seen since Canada, in particular to certain seasonal conditions. Our observations in answer to his questions were lame, at best, and I suddenly felt like I’d just walked 1,500 miles and failed to notice most of what was going on around me. Then John explained he was gathering data on warming trends in the Rocky Mountains and what effect it was having on the alpine and subalpine ecosystems. I didn’t realize it at the time because ‘global warming’ had yet to come into the lexicon, but John was an early researcher into climate change. After failing miserably at his biology quiz, John changed-it up a bit and asked about anything “odd or strange” we had experienced along the way. I shrugged and, rather off-the-cuff, mentioned the Bigfoot tracks we’d followed in northern Montana. At the mention of Bigfoot, John lit-up “That’s exactly the kind of thing I’m talking about!” he exclaimed. He pulled material from a large bookshelf against the wall and showed us a collection of information and data he was compiling on Bigfoot and very much wanted us to send him copies of the footprint photos we had taken. Then he told us about his own Bigfoot sighting but, like everybody else, didn’t get a picture. The evening grew late, so John suggested we just throw our sleeping bags out on the cabin floor, which we were very grateful for when bad weather blew-in during the night. Wind and rain continued to lash at the cabin the following morning and persisted through most of the next day. John, who was obviously happy to have some company around, encouraged us to just stay put until the weather passed. Looking out the window, I knew the wind and rain was really just a mental block because all we had to do was put on our rain gear and start walking, but neither one of us could muster the fortitude to cut loose of the cabin to go out and walk muddy roads in miserable weather, so we stayed put.

thanks and goodbye, John kept us engaged in conversation and offered up more coffee. I was anxious to get going but we had another cup then got up to leave. John stood as we did and said “Let me drive you down the road a short piece. It’s easy to get lost up here, I’ll just get you down to where it’s safe.” And I was like “No, no, really, we’ve got maps, you know, we’ll be fine.” But he was already grabbing his truck keys and throwing on his jacket. “Come on” he said. Craig and I both hesitated but as we stood there, John hopped in the truck and waved for us to get in, so we threw our packs in the back and got in. After about fifteen minutes of bouncing along a mesa top, two-track road, I turned to John and said, “Hey, really man, this is good. Why don’t you let us off and we can walk it from here.” But he wouldn’t pull over, just saying, “Nah, hang-on, I’ll get you out to where it will be okay for you guys to walk.” Well, this was certainly different, I’d just asked this guy to pull-over and let us out and he’d refused. Another five minutes passed and again I said “Hey, John, we’re supposed to be walking this, you know, why don’t you let us off right up here.” To which he just kind of laughed and said, “Hang-on, we’re almost there.” Now I’m thinking ‘What the heck… “almost there” - almost where??’ We were in the middle of some of the most barren, no-man’s-land I’d ever seen. Then, coming over a slight rise in the road, John stopped the truck and shut off the engine. He pointed out to a faint butte on the horizon and said, “Head for that butte out there, stay north of it and South Pass is just beyond.” He looked over at us with a big smile and I could tell he was pretty pleased about being able to point out the desert’s first landmark to us. Okay, well, that was a relief, I don’t know what I thought was going to happen but John just wanted make sure we got out to South Pass, which was crucial to our route. We grabbed our packs from the back of the truck and thanked him several times over for his hospitality and help in preparing us for the desert as we shouldered our loads. I could tell John was happy to have been a part of our story and also pretty entertained that a couple of guys on foot, navigating their way to Mexico, would come right through his homestead. John waved, turned the truck around and drove off, leaving us staring out at the last vestige of hills before an expanse of overwhelming nothingness. The butte John had pointed out was so distant as to appear only as a wavy, mirage-like feature on the horizon and out ahead of us stretched a ruler-straight ribbon of gravel road that vanished off in the distance long before reaching the butte. Looking down that barren road, I felt like we were wandering out onto the face of the moon. Go to Part 55

September 13-16 Lander, WY (Go to Pt 1) The following day we made the long, dusty march out of the mountains down to Hwy 187, arriving late in the day, beat-down tired. I don’t recall much about the hitch-hike to Lander, only that we got in after dark.

across the street, then decided to walk over and see if they had any nuts or chips or something else to eat, which they didn’t, so instead we returned with a bottle of Jack Danial’s. Back in the room we cracked the whiskey and took a pull. “Ooo, shit-dang!” It was terrible, like drinking turpentine. “Why’d we used to drink this shit?” I sputtered. But after about fifteen minutes and another pull I started to remember why as I melded back into the cracked, vinyl chair, feeling more relaxed than I’d been in weeks. Craig and I started to laugh at the crappy motel room and the dented-up pick-up trucks pulling through the liquor store’s drive-through window across the street. The whole scene became rather comical, from the peeling wallpaper and dime-store, cowboy pictures on the wall to the threadbare bedding and our ‘scenic overlook’ view of beat-up pick-up trucks and neon lights across the road. Then we began reminiscing about the trip, anecdotes of our various misadventures along the way, all of them funnier than shit because they hadn’t killed us. We talked about our luck at having descend out of the high peaks in the Wind Rivers just before the snowstorm hit, and speculated about the trouble we would have been in had that storm caught us up high on the Continental Divide. Without landing on any of the real trials and tribulations we experienced in the Wind Rivers, the conversation turned toward the Great Divide Basin and the Red Desert, the next stretch out in front. I was hesitant about this look forward and held back from commenting very much as Craig, with a little help from Jack, talked enthusiastically about dispensing with the Red Desert and moving on to Colorado. As we began to banter back and forth the logistics of crossing the desert, there were two things running through my tired, rubbery brain; first, based on what was probably whisky optimism, Craig was sounding intent on heading into the Divide Basin (I guess because he hadn’t been forced to his knees screaming “uncle” yet) and second, this was not exactly what I’d expected, because part of me had really thought that Craig was going to call this the end-of-the-trail, but that’s not at all what was happening. Craig ended up asking is if I’d be OK with one extra day in Lander to give his knees a “rest”. I almost had to laugh at this “one extra day” request because, as I saw it, anything short of a month wasn’t going to revive or rehabilitate a thing, especially not his knees, but I did have to admit, extra rest sounded like a swell idea. “Sure, let’s take an extra rest day.” And with that, we capped the Jack. The next morning was pretty rugged, the drunk from the night before had kind-of wrecked my sleep and we were both hung-over, cotton-mouthed and blurry around the edges until we could find some orange juice and something to eat. The daylight glare was harsh and the short walk to the café seemed to take longer than I’d remembered from the night before. We ate breakfast and drank a pitcher of orange, which helped to steady the ship, but after the plates were cleared away lethargy set-in, hard. From the café, it wasn’t far to the Post Office where our desert gear was waiting to be picked-up but we paid our bill and returned to the motel instead, napping on and off the rest of the day in a fog of fatigue. The following day did not shake the lassitude that still had us moving in absent-minded, slow motion. After a sluggish start to the morning, we set about collecting our desert gear from the Post Office, sending the Wind River equipment back to St. Louis, then running a load at the laundromat while picking-up supplies at the grocery store. Back at the motel room we dumped everything out on the floor for sorting and packing then sat down at the little table by the window and polished off the rest of the whiskey. As the glow returned, we dug through our supply package for the map-set covering the Divide Basin which we spread out on the bed to examine. We had 7.5, largescale quadrants from Lander down to South Pass but only a couple of 250,000 series maps of minuscule scale to cover the entire expanse of the Great Divide Basin (Red Desert) down to Interstate 80. Sketching out our route from Lander into the Divide Basin and then out across the desert wasn’t very hard; some foothill wandering down to South Pass then dirt roads hugging the western edge of the basin into a whole lot of brown nothingness. Finding water on the 250,000 series map would have been a real head-scratcher had it not been for some key information we’d gotten from the northbound, Continental Divide hikers six weeks earlier. Undeniably, this was the bleakest stretch of the entire Continental Divide with the only upside to this barren country being that maybe Craig would be able to walk the flat, featureless terrain, as he anticipated. After we’d seen enough desolation on the maps, we wandered back to the café and tried to forget about the desert for a while. The next day was our add-on, rest day and by early afternoon it had already turned into shear boredom with our packs sitting by the door, ready to go. I was starting to get a little agitated about hanging out here just to give Craig’s knees a ‘rest’ - like that was going to fix anything - when we, or at least I, should have been out on the Divide, clocking miles. At the same time, the reality of continuing this journey without Craig was also taking hold, sending a deep current of fear and doubt through me; I did not want to walk out into that desert alone, I really didn’t, and, at that moment, I was glad Craig was going into the desert with me. But what I really wanted heading into the Divide Basin was ‘Montana’ Craig back in the game, the guy who was always ready and steady, no matter what came along. But that guy had vanished. ‘Clipped by an arrow’ on Lava Mountain… and he wasn’t coming back. Go to Part 54

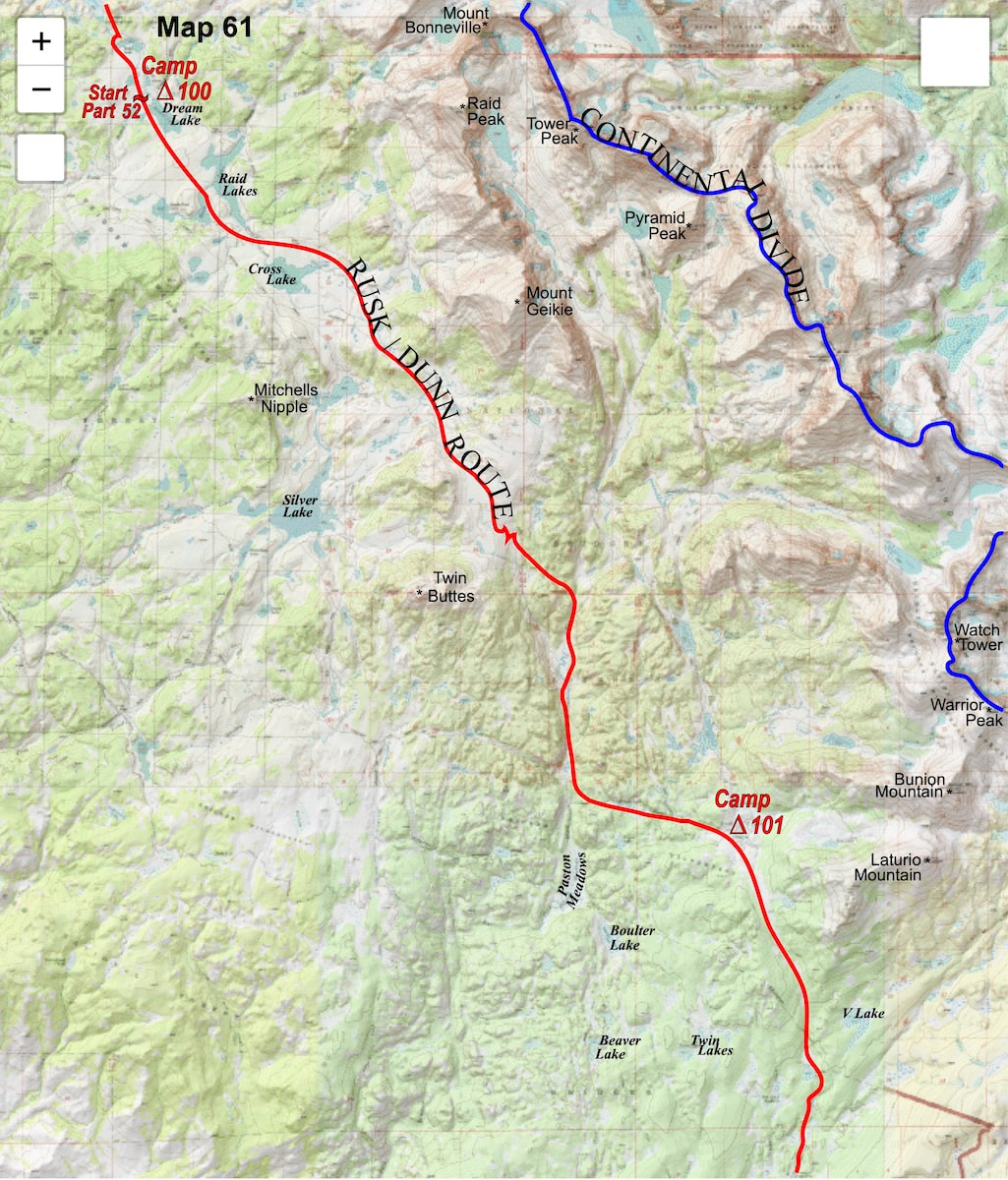

September 11th - 13th Wind Rivers, WY (Go to Pt 1) September 11 Sunrise over Raid Peak the following morning was gradual, gaining strength as it reached the crest of the eastern ridge before spilling warmly out across the lake. It was calm and peaceful by the water’s edge and I sat down by the lakeshore for a while before collecting water, just absorbing the serenity.

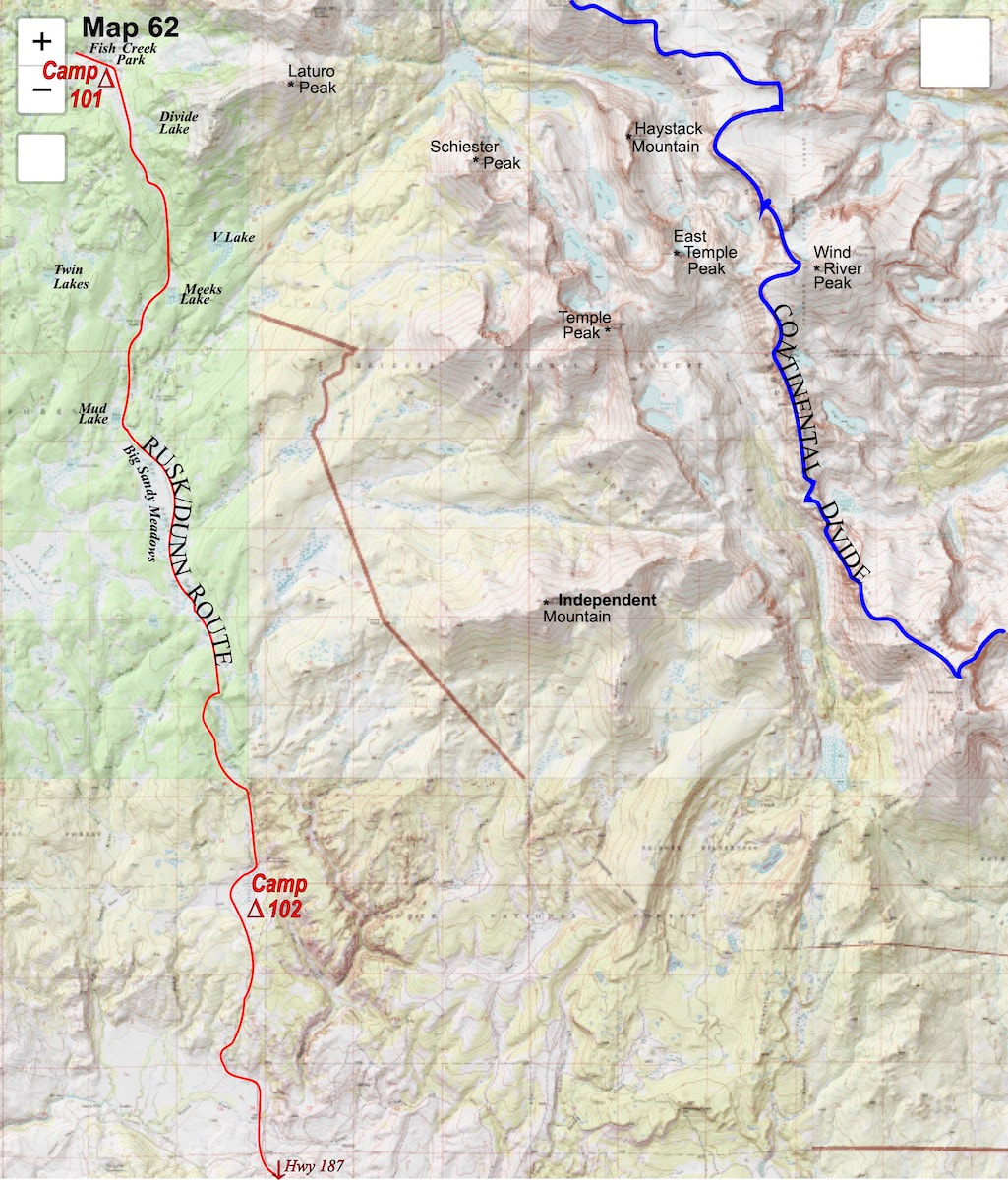

By late afternoon, under clear, warm skies we had reached Fish Creek Park, a large expanse of meadow where we dumped our packs and rested for a while. Then, after that while was over, we decided to fish around in our packs for something to eat. We had hoped to make it further down valley before making camp but, at this point, spending the night in Fish Creek Park was already happening.

If we had come down along the eastern side of the mountains, as was originally planned, we would practically be into Lander by now, but our being forced down to the Highline Trail on the western side now put us on the wrong side of the mountains with a particularly wild section of the Continental Divide standing between us and Lander. The maps we did have showed steep, dead-end canyons and soaring, nearly-impenetrable peaks thousands of feet above the valley.

This was our 16th day in the Wind Rivers and we had packed 16 days’ worth of supplies; we had one meal left, some extra rice, a couple of packets of instant soup and oatmeal and very little fuel left for the stove. Even if we did end up putting a route together that got us across the mountains, we were at least two, and maybe even three days from hiking the nearly 50 miles that lay between Big Sandy and Lander. We had not intended to come out at Big Sandy and now we were out of supplies and route options, we were going to have to walk out to Hwy 187 and hitch-hike around the southern toe of the range and then back up to Lander on the eastern side. We ended up camping a ways down from Big Sandy Meadows, mentally and physically wiped-out.

September 13th The following day we made the long, dusty march out of the mountains down to Hwy 187, arriving late in the day, beat-down tired. I don’t recall much about the hitch-hike to Lander, only that we got into town after dark. Go to Part 53

|

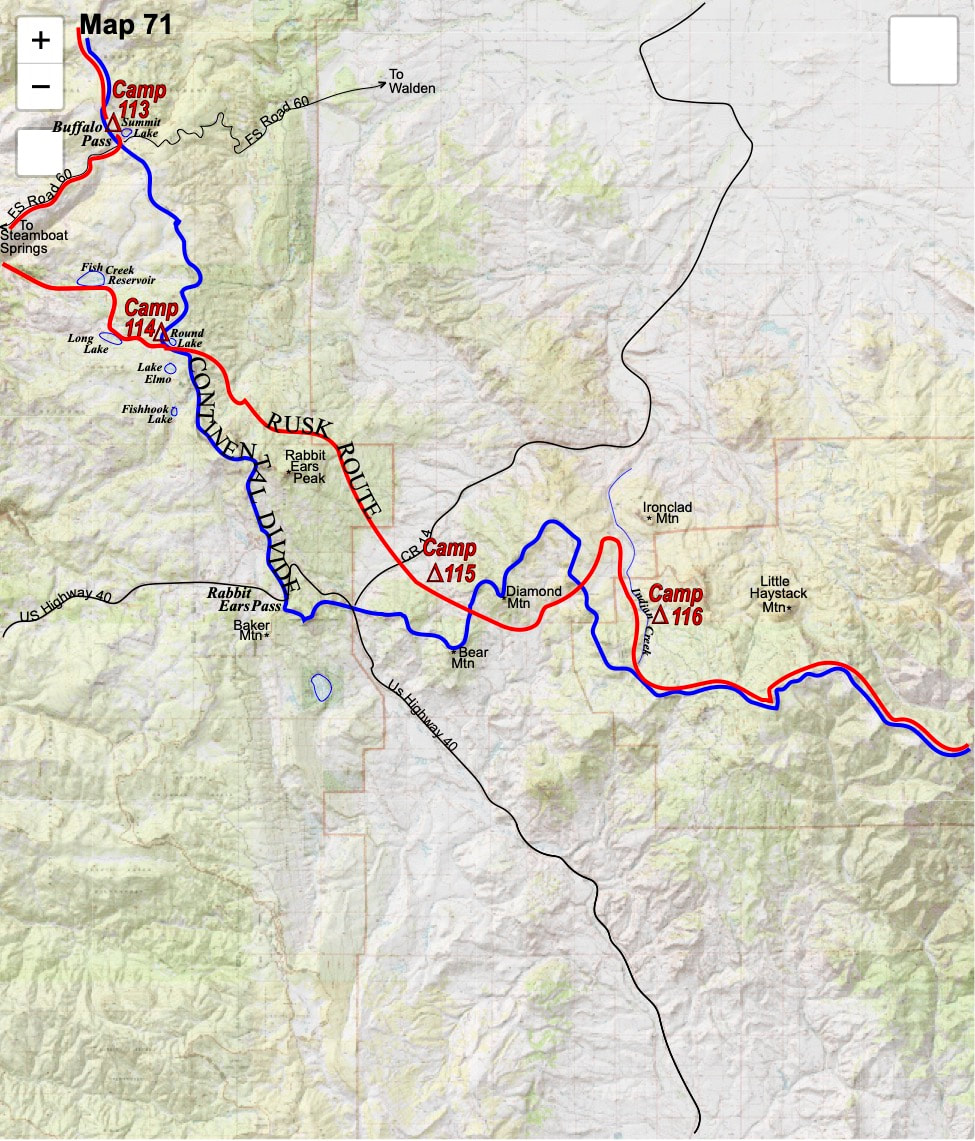

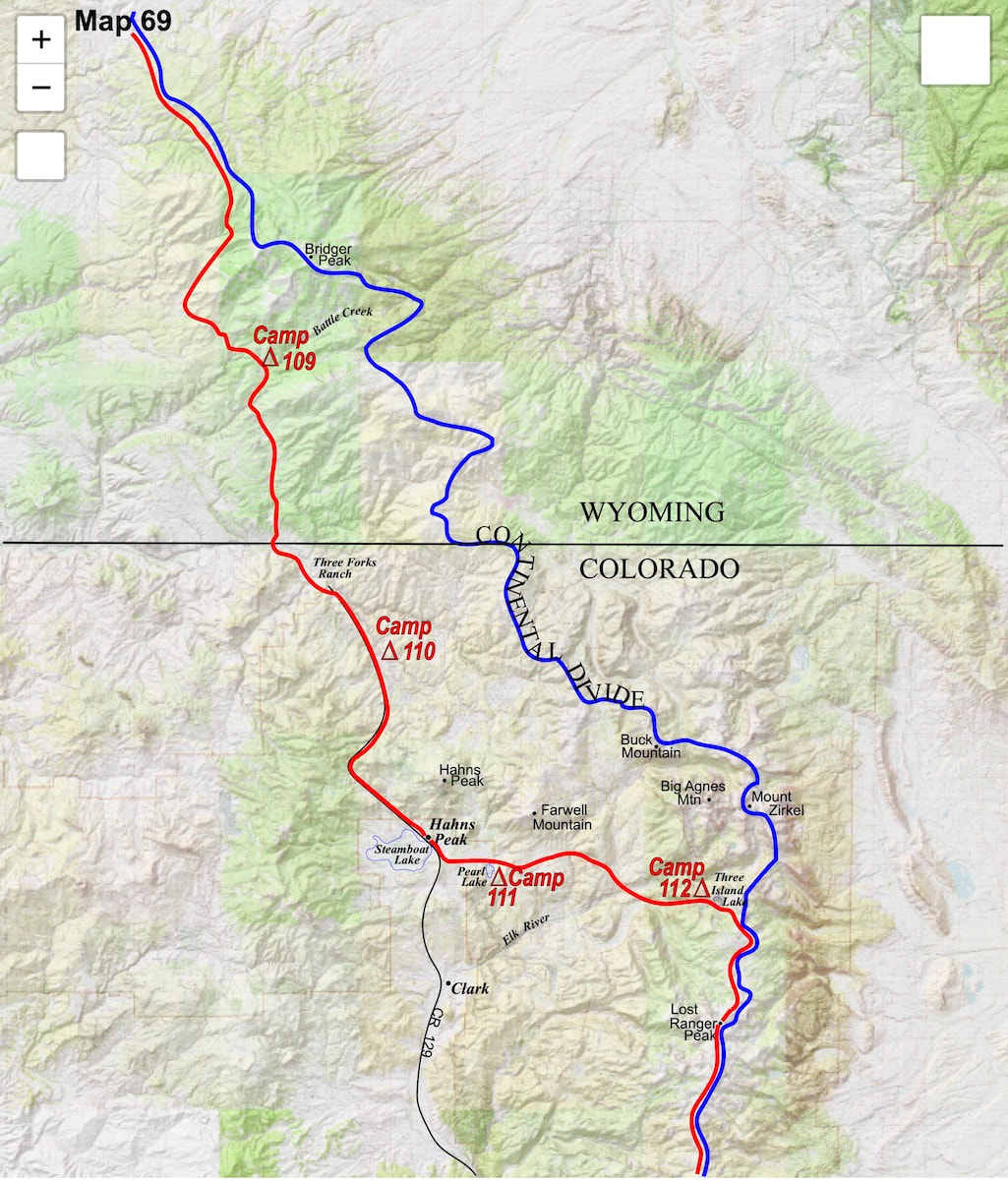

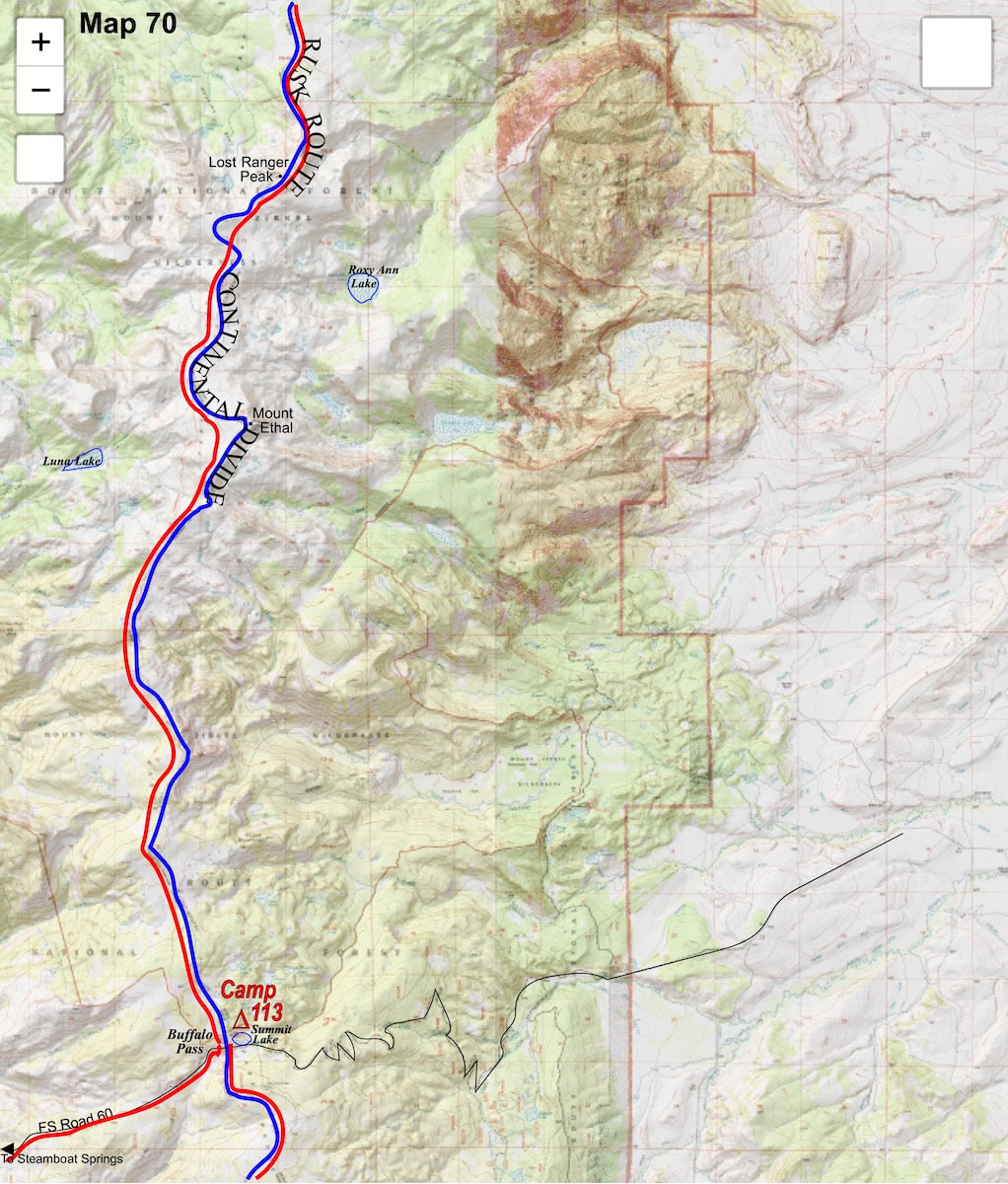

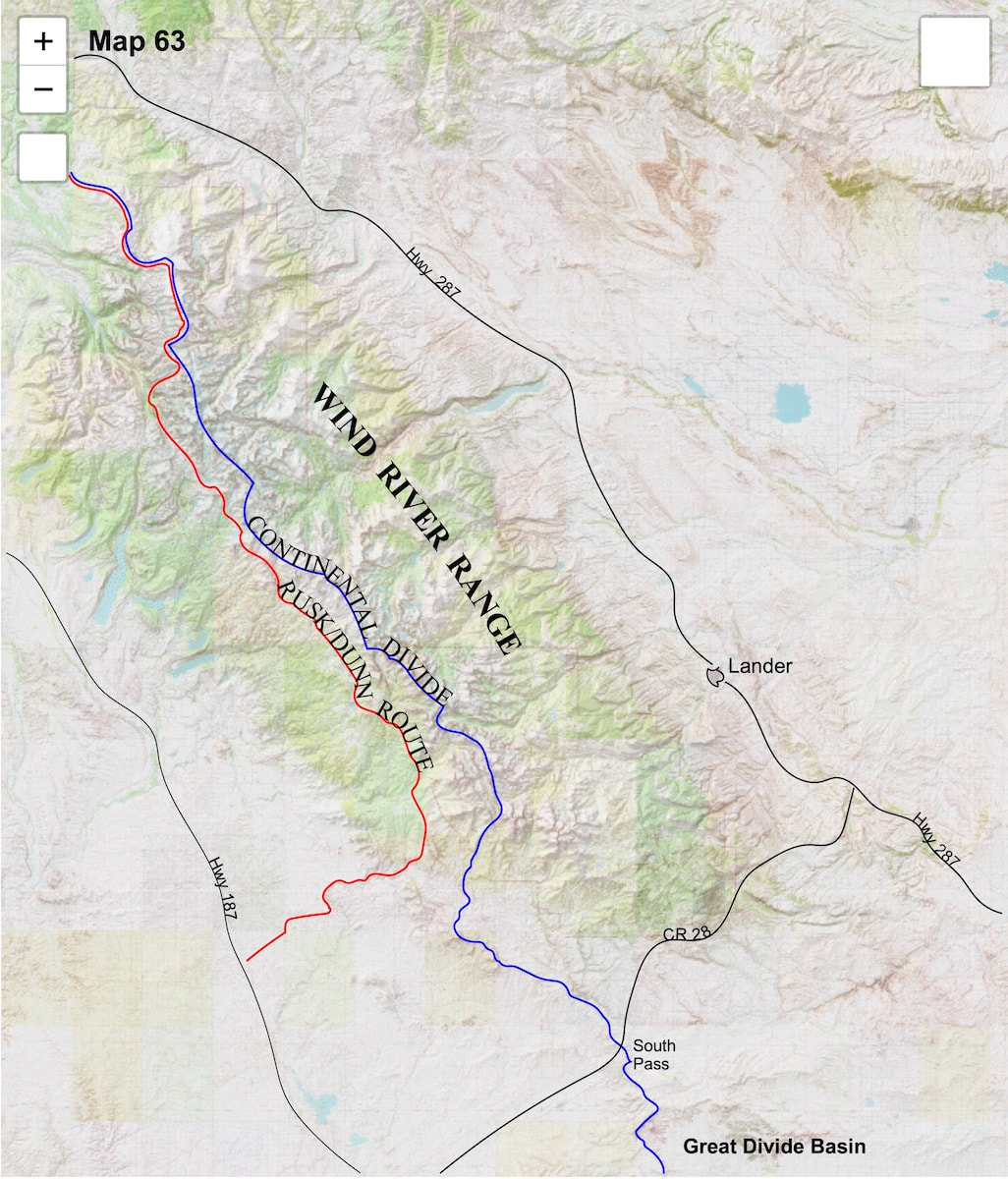

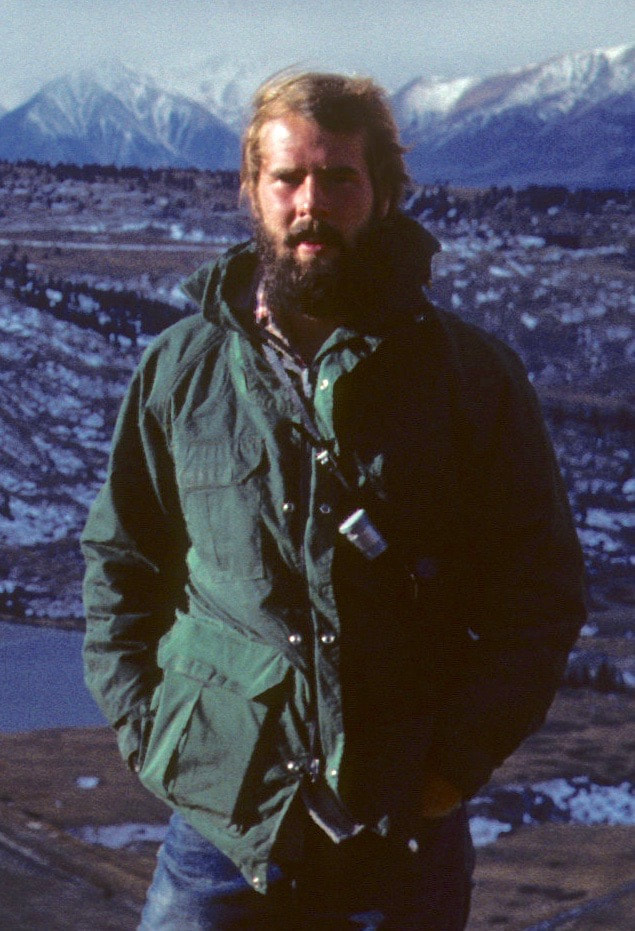

Kip RuskIn 1977, Kip Rusk walked a route along the Continental Divide from Canada to Mexico. His nine month journey is one of the first, documented traverses of the US Continental Divide. Montana Part 1 - Glacier Ntl Pk Part 2 - May 11 Part 3 - May 15 Part 4 - May 19 Part 5 - May 21 Part 6 - May 24 Part 7 - May 26 Part 8 - June 2 Part 9 - June 5 Part 10 - June 7 Part 11 - June 8 Part 12 - June 11 Part 13 - June 12 Part 14 - June 15 Part 15 - June 19 Part 16 - June 23 Part 17 - June 25 Part 18 - June 27 Part 19 - June 30 Part 20 - July 5-6 Part 21 - July 7-8 Part 22 - July 9-10 Part 23 - July 11-15 Part 24 - July 17-18 Part 25 - July 18-19 Part 26 - July 19 Part 27 - July 20-21 Part 28 - July 22-23 Part 29 - July 24-26 Part 30 - July 26-30 Part 31 - July 31-Aug 1 Part 32 - Aug 1-4 Part 33 - Aug 4-6 Part 34 - Aug 6 Part 35 - Aug 7-9 Part 36 - Aug 9-10 Part 37 - Aug 10-13 Wyoming Part 38 - Aug 14 Part 39 - Aug 15-16 Part 40 - Aug 16-18 Part 41 - Aug 19-21 Part 42 - Aug 20-22 Part 43 - Aug 23-25 Part 44 - Aug 26-28 Part 45 - Aug 28-29 Part 46 - Aug 29-31 Part 47 - Sept 1-3 Part 48 - Sept 4-5 Part 49 - Sept 5-6 Part 50 - Sept 6-7 Part 51 - Sept 8-10 Part 52 - Sept 11-13 Part 53 - Sept 13-16 Part 54 - Sept 17-19 Part 55 --Sept 19-21 Part 56 Sept 21-23 Part 57 - Sept 23-25 Part 58 - Sept 26-26 Colorado Part 59 - Sept 26 Part 60 - Sept 30-Oct 3 Part 61 - Oct 3 Part 62 - Oct 4-6 Part 63 - Oct 6-7 Part 64 - Oct 8-10 Part 65 - Oct 10-12 Part 66 - Oct 11-13 Part 67 - Oct 13-15 Part 68 - Oct 15-19 Part 69 - Oct 21-23 Part 70 - Oct 23-28 Part 71 - Oct 27-Nov 3 Part 72 - Nov 3-5 Part 73 - Nov 6-8 Part 74 - Nov 9-17 Part 75 - Nov 19-20 Part 76 - Nov 21-26 Part 77 - Nov 26-30 Part 78 - Dec 1-3 New Mexico Part 79 - Dec 3-7 Part 80 - Dec 8-11 Part 81 - Dec 12-14 Part 82 - Dec 14-22 Part 83 - Dec 23-28 Part 84 - Dec 28-31 Part 85 - Dec 31-Jan2 Part 86 - Jan 2-6 Part 87 - Jan 6-12 Part 88 - Jan 12-13 Part 89 - Jan 13-16 Part 90 - Jan 16-17 Part 91 - Jan 17 End |

© Copyright 2025 Barefoot Publications, All Rights Reserved