|

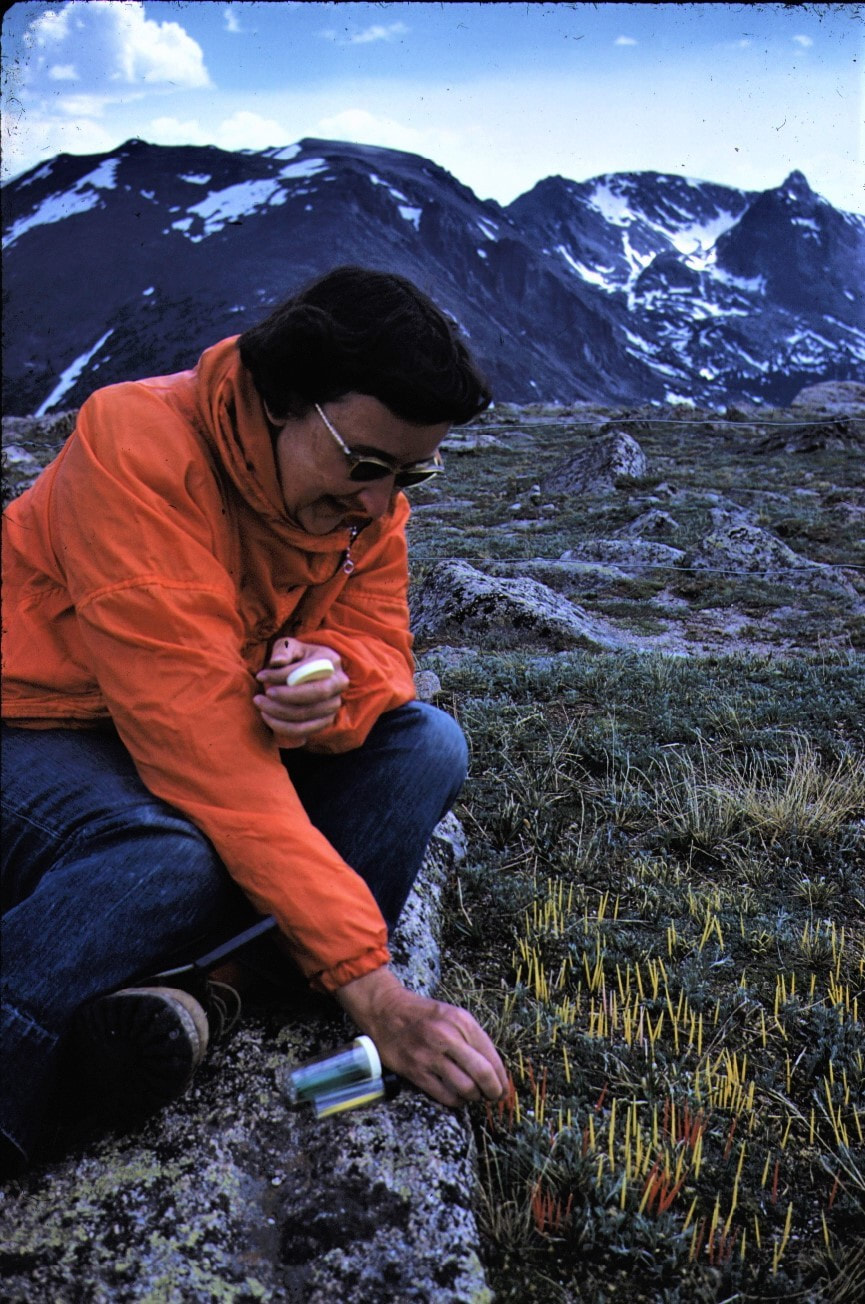

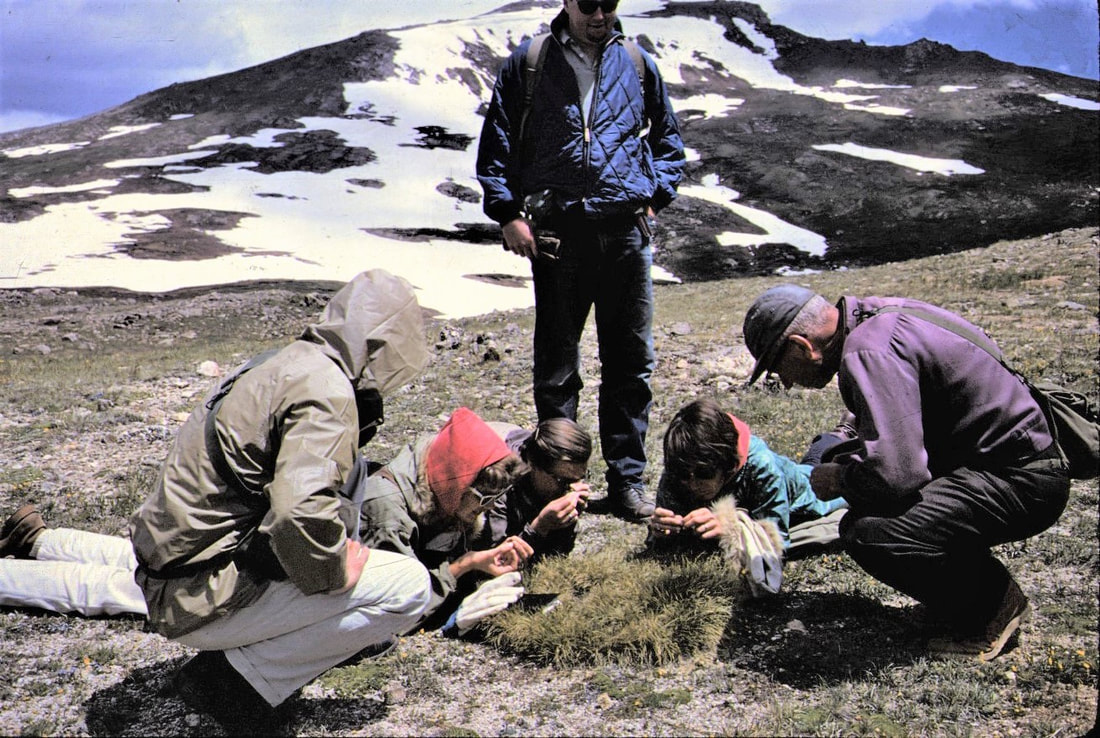

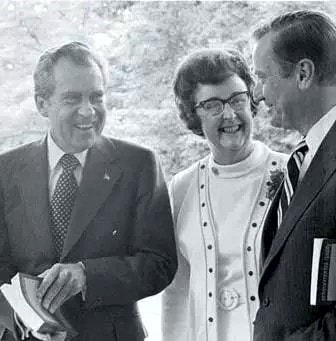

It is illegal to walk on the tundra in Rocky Mountain National Park at Fall River Pass, Gore Range, Rock Cut, Lava Cliffs and Forest Canyon Overlook. For reasons which will be explained, concentrated visitor use atthese areas poses a proven threat to the delicate tundra. HOWEVER, other areas of the alpine tundra, which is one-third of the Park's terrain, can be traversed upon; albeit, very lightly. Walking is not the preferred way to study this ecosystem up close. “Belly Science” – first developed by Bettie Willard – puts you on the tundra face down, spreading your weight across plants that have survived the harshest of climates for hundreds of years. The ground is surprisingly soft and supple, even furry in places where fine white hairs grow over leaves and petals, protecting each tiny plant from hurricane- force winds and near-freezing overnight temperatures. Fragrant, floral, clean and airy: the smells of the tundra are reserved for those who have the audacity to stick their noses into it. (see Rocky Mountain National Park’s policy on tundra use) This is a world where the smallest of organisms create a community of symbiotic relationships, each plant working with each pollinator to help feed its neighbors and expand vegetation above treeline, a world where roots run deep and plants stay short, with impossibly- bright blooms spreading out to hug the horizon, all the way up to the vertical end of the world. Respecting this world is paramount and understanding its legacy is just as profound. Bettie Willard's National Park work Bettie Willard always dreamed of being a National Park Service ranger, especially after she attended the Yosemite Field School in the summer of 1948. For that entire summer, she and other attendees lived in tents and worked in the wilds of Yosemite National Park, studying nature up close. Graduates from the field school – 16 men and four women – were then interviewed by the National Park Service, but Bettie's dream of being a ranger was dashed: “Don't you know? We don't hire women for those positions,” she was told. It didn't matter that she had just graduated from Stanford University with a degree in biological sciences or that she already had a lifetime of experience guiding through the wilds near Mammoth Lakes, California, where she spent summers with her parents. It only mattered that she was female. Willard dealt with mid-Century norms for women throughout the rest of her life but this environmentalist was not daunted. She had made an influential friend: Dorr Yeager, Rocky Mountain National Park's first naturalist and author of the “Bob Flame, RMNP Ranger” novels. Over the next several years, he asked around and found only four National Parks that were willing to hire women; one of these, Lava Beds National Monument (est. 1925), finally hired her as a ranger for the summer of 1952. The following summer, she was a ranger at Crater Lake National Park (est. 1902). When asked later in life how she got along as the only female ranger in those Parks at that time, she said that she did a lot of observation at first, finding out which rangers worked in which department or niche. Willard filled neglected niches, thus preventing stepped- on toes (and egos) of the more established, male rangers. She prided herself on complementing – not competing with – what the other rangers were doing. Between her undergraduate studies and this life goal achieved, Willard attended UC Berkeley to become a teacher. She taught in Salinas, then Oakland and finally general studies at Tulelake High School, located in California near the Oregon border. It was considered a rural school and eligible for the newly formed Ford Foundation educational grants. In 1954, she was awarded a $4,600 scholarship which “was enough for her to go to Europe for 14 months to study vegetation on the high mountains. She wanted to study the vegetation in the Alps, in Scandinavia and other places in Europe,” explained Leanne Benton, co-instructor for the Rocky Mountain Conservancy's “Bettie” Course: “Tundra Pioneer: the life and legacy of Bettie Willard,” held on July 20. Benton is a long-time Rocky Mountain National Park volunteer and taught this course with Cheri Yost, the current Park Planner for Rocky. While in Europe, Willard attended a conference of 2,000 international botanists in Paris and made valuable connections which led to several field trips in Switzerland to study alpine plants. “She also met a woman, Ruth Ashton Nelson, who was a Colorado botanist and had already published a book on the plants of the Rocky Mountain National Park,” Benton said. By the time Bettie was finished with her European studies and work, she knew she wanted to go to grad school and study American alpine plants, specifically to compare those with the plants she had studied in Europe. But first Willard had to fulfil the requirements of the scholarship by teaching two more years at Tulelake. In 1957, she enrolled in the University of Colorado at Boulder to study ecology. “Ecology really came into its own in the late 1890s and women were getting ecology degrees since the 1910s,” Cheri Yost explained. “But most women ecologists were either working with their more famous husbands, like Edith Clements, or they were teachers. They really weren't doing their own independent research.” But by the late 1950s Willard was doing just that, under the instruction of noted arctic and alpine ecologist John W. Marr. Willard wanted to study “plant sociology” (like she did in Europe) on the alpine tundra in Rocky. She established a plot at Rock Cut in 1958 that was 10 square meters large (current pipe fencing at Rock Cut includes her original plot). The same trail that she used through this area can still be seen, standing as a testament to the long recovery time for disturbed tundra. A second plot was established at the newly-built Forest Canyon Overlook. Her studies at several spots on Rocky's tundra led to the completion of her master's and then her doctorate, from the University of Colorado. “What she was noticing was that visitor use was having a huge impact on the tundra,” Yost said. Willard needed to convince Park managers that visitors were having an impact on this delicate area and that something had to be done about it. She thought the trails on the tundra should be paved and hardened, “if you pave a trail, people will stay on them,” was her argument. Next, she wanted Park managers to “stop the craziness in the backcountry,” because there were no rules about camping in the backcountry in Rocky. And finally, Willard wanted people to become stewards of the tundra through education and experience. She accomplished these goals by utilizing the skills, hard work and diplomacy that she had always applied working in the heretofore “man's world” of the National Parks. Visitor impact was proven through vast data sets – collected by Willard and others - that tracked alpine environments. Mission 66 (which was launched in the mid-1950s) provided the infrastructure funds to pave the areas she recommended, and her experience with backcountry “craziness” in her research both above and below treeline led to the establishment of backcountry camping permits in the early 1970s. Willard started teaching the first field seminar program in Rocky Mountain National Park, through the Rocky Mountain Nature Association (now the RM Conservancy). “She taught the alpine field seminar for many, many years in the Park,” said Yost. Willard was also instrumental in getting alpine rangers in Rocky to teach the public about the tundra and in the placement of signage and educational displays in the Alpine Visitor Center and other places. For 40 years, Willard came back to study her alpine plots every summer in Rocky, funded in part by the Department of Defense (since the country was still at war in various arenas). “She took photos of her plots, put toothpicks down to mark the individual plants, and tracked those plants for the entire time she worked in Rocky,” Yost said. Today, Jackson Maldonado, Alpine Community Science Intern, is continuing Bettie's work in much the same way. This summer was the kick-off of a continuing community science project that will encompass two programs: one with trained volunteers doing surveys at Willard's original plots and the other program designed for community members. It will teach them about climate change effects on the tundra, and the phenology (or life-cycle) of tundra plants and include an excursion onto the tundra to identify its wildflowers. “If we can get a solid data set that builds off of what Bettie started, we can really track the impacts climate change is having on the tundra,” Maldonado said. He spent much of the summer working with Park employees to create the parameters, logistics and study scope of the project, which will kick off its first year of serious study in the summer of 2024. Bettie's "experiments in ecology" But Bettie Willard's story doesn’t end with her important conservation work in Rocky. She wrote Land Above the Trees: Guide to American Alpine Tundra with Ann Zwinger in 1971. “This book was instrumental while I was learning about the tundra as an RMNP ranger,” said Leanne Benton. Moss campion, a cushion plant, is one of the “champions” of the tundra, Benton said, growing only about ½ inch by the time it's five years old. “It doesn't really start to bloom unless it's about 10 years old and by the time it's 20-25 years old it's about 7 inches wide and blooming profusely. “Think about what a grinding footstep can do to a plant like this,” Benton said. After Willard achieved her doctorate, she stayed in Boulder and helped to found the Thorne Ecological Institute. In 1965, she became its Executive Director, in 1967, she was its vice president; and, in 1970, president. “Thorne's mission was to help people understand the relationships in the environment and develop a personal concern for the Earth,” explained Cheri Yost. “While Willard was at Thorne, it put her at the forefront of many environmental partnerships.” Willard went on to form and/or serve with numerous environmental organizations throughout the state, excelling at collaboration. “In 1966, she created what she called 'the experiment in ecology,' ” explained Yost. “She really believed that all of these conversations were a three-legged stool: engineering, economics and the environment. If you could not get these three concerns to talk to each other, you are not going to be successful stewards of health and society.” Working with the mining industry along with environmental concerns in Colorado, Willard created “a safe space to work out differences so meaningful and lasting agreements could be made,” Yost explained. “We fostered abundant measures of openness, objectivity, willingness to tell all, an ability to listen and believe but to question until Truth comes forward,” Willard said of this time in her life. Working for the Federal Government In 1969, Congress passed the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), which codified Willard's “experiment in ecology,” on a national level. Its mission was to bring every new environmental policy in front of everyone who would be affected by it. The next year, President Richard M. Nixon appointed Willard to the President's Council of Environmental Quality (CEQ). She was the first woman to serve on this council, which existed to educate everybody in the country on NEPA. “Most of the environmental laws on the books today were put in under the Nixon Administration,” explained Yost. Willard received many letters of congratulations for her service with the federal government, but nearly every one of them contained some back-handed compliments, essentially: “pretty good – for a woman.” For the rest of her life, Willard went on to champion common-sense environmental laws in Colorado and nationwide. For example, said Benton, there were several things that Willard did to help mitigate the environmental issues with the Alaskan Pipeline during its NEPA process. “She made about 15 trips up to Alaska during that time to look at the route planned for the pipeline and was instrumental in getting the pipeline raised above areas of permafrost (so it wouldn't melt) – and raised high enough to not interfere with caribou migration.” Willard was not against development. “She worked for Nixon, she was a Republican,” Yost said. “She was the head of the Colorado Olympic Committee in 1970 when Denver was awarded the 1976 Winter Olympics. She didn't have any concerns about the Olympics itself, she had a problem with the necessary, uncontrolled building that was going to happen next to it.” Ultimately, voters in Colorado voted against holding the 1976 Winter Olympics in the Colorado Rockies, making it the only state to ever refuse the offer. Bettie returns to Colorado to educate on environmental issues in the state Bettie Willard returned to Boulder after the change of administration and after a few years, “she was approached by the Colorado School of Mines, one of the foremost mining schools internationally, to set up a department of environmental sciences, looking at how to mitigate the effects of mining,” Benton explained. When she was interviewing for the job, she asked the president of the board: 'How do you feel about working with a woman?' She accepted, but only after being assured that anyone exhibiting chauvinistic behaviors would not be tolerated at the school. She developed the brand-new department and created 28 classes, many of which she taught herself. Thirty- two students graduated with the Minor degree she designed, but still, she didn't feel equal to her fellow professors. “She felt some type of discrimination,” Benton said. In 1982, she took a leave of absence: two years without pay. Nevertheless, she traveled, cross-country skied, taught, and wrote books (many of which are some of Benton's most treasured possessions). When it came time to return to the School of Mines, she just didn't want to and “resigned” in 1984. For the rest of her life until she was no longer able, Bettie Willard wrote books, taught, served on groups and committees and taught seminars. “She taught seminars here (for the Rocky Mountain Conservancy) until 1996,” said Benton. “I was able to take a course from her in 1995,” Benton recalled. This experience really cemented Benton's commitment to Rocky. “She was a very gifted teacher,” Benton said. Bettie Willard passed away from Alzheimer's disease in 2003. You can continue Bettie's legacy at Rocky! Jackson Maldonado is looking for some people to practice Belly Science with him next summer, through his Alpine Community Science projects. You can reach him with questions at [email protected]) Like Willard, Maldonado dreams of working for the National Park Service after he graduates. “I would love to make Parks more accessible, everyone deserves to be in green space, to experience nature, safely.” He admires Bettie Willard very much. “The work that she accomplished locally, regionally and nationally positively impacted so many people and the environment.” (Maldonado's views do not necessarily reflect the goals and ideas of the National Park Service.) Like Bettie, Leanne Benton grew up in California. In college, she took a summer Park Ranger job at Rocky; “It was a life-changing summer – I loved the work and the Park. For four more summers I worked as a seasonal Park Ranger on the west side. I met my husband one of those summers who was also a Park Ranger.” After years of working as a full-time Park Ranger for several NPS units, Benton returned to Rocky to manage the Alpine Visitor Center for eleven years. She continues to volunteer with Rocky.  “In Land Above the Trees (1972), Bettie Willard and Ann Zwinger brought together most of what was known about alpine tundra in the U.S., including Bettie's research, and presented it in a book that was understandable for a wide audience,” Benton said. “The book was a huge success. The information so poetically presented in the book illuminated the fascinating adaptations of the plants and animals for survival in the alpine world. Land Above the Trees was THE BOOK that all the park rangers read to learn about alpine ecology so we could effectively communicate with the public. This book continues to be relevant today. The results of Bettie's research and recommendations also laid the foundation for how Park Managers protect the park's tundra, while also allowing public enjoyment of the tundra. Bettie also recommended the importance of education in protecting the tundra.” Benton wants you to remember that while traveling on the tundra, move like a herd of elk, not a line of people. Step on stones or gravel where possible and if there is a trail, use it. Cheri Yost has spent most of her NPS career translating science, which is how she was introduced to the remarkable legacy of Dr. Willard. She is currently the Park Planner.  Barb Boyer Buck is the managing editor of HIKE ROCKY magazine. She is a professional journalist, photographer, editor and playwright. In 2014 and 2015, she wrote and directed two original plays about Isabella Bird and Rocky Mountain National Park, to honor the Park’s 100th anniversary. Barb lives in Estes Park with her cat, Percy.

0 Comments

story, photos and video by Barb Boyer Buck Driving up to Estes Park from the Front Range, you travel on roads that were cut through dense layers of basement rock, pushed up from the ground in what looks like a violent fashion. The sight humbles me; I feel quite small, even though this happened millions of years ago. I have to remind myself these rocks are stable enough to support roads that carry four million people to Rocky Mountain National Park each year. The majestic Rocky Mountains that come into view as you dip down into Estes Park look like timeless unchanging sentinels of this mountain valley. But in reality, they are constantly evolving. “There are about seven different plates floating around on the skin of the mantel of the Earth,“ explained Roy Dearen, retired geophysicist and environmental geologist who now lives in Estes Park. “Kind of like a skin on an onion, they are thin and less dense than the mantel below them so they float at a very slow speed, about the speed of your fingernails growing. The Pacific plate and the North American plate are pushing against each other in opposite directions. That's how the ancestral Rockies were formed. The tops of these mountains, at one time, were at least 20,000 feet above sea level.” Roy was born and grew up in Texas; he moved to Colorado in 1975. In 1981, he earned a degree in geology from the University of Colorado at Boulder. He has worked for American Copper & Nickel as a geophysicist, as a seismic interpreter for oil and gas exploration and supervised clean-up operations at the Rocky Flats Nuclear Weapons Plant in the mid-1990s. But I suspect it's his experience as a third and fifth grade teacher at Lyons Elementary School that makes him such a great person to interview on this subject. He makes geology accessible and easy to understand. Roy was kind enough to meet me to discuss the rocks of the Rocky Mountains, specifically those in Rocky Mountain National Park. He shared a geology presentation he gives while conducting tours of Rocky. At a small pull-out in Horseshoe Park just before Sheep Lakes, Roy encourages everyone he takes on this tour to turn toward where Longs Peak sits. Then, he explains the geologic history of the Park, from 90 million years ago until the present. Words are not adequate to put this information into perspective so in the video below, the entire presentation is recreated. But the only way to really experience the unique geology of Rocky is in person. The rocks of the Rocky Mountains are products of erosion and displacement, pulled inexorably downward by gravity. On a tour of the Bear Lake Corridor early this week, Roy showed me some of the more unique rock formations of the area. Of particular interest was a stretched pebble conglomerate: an interesting boulder that collected large pebbles as it was formed, the pressure of the metamorphic process elongating the pebbles in a distinct direction. We were also on the hunt for gneiss (pronounced “nice”). These ancient rocks were formed deep in the Earth, from granite heated to the consistency of toothpaste and squeezed through the cracks in the harder schist layers. Retreating glaciers after the last ice age tumbled the rocks, rounding them in the same process a rock- tumbling machine does. In the large, peaceful parks within Rocky, these round rocks look like they had been placed there by a landscape designer. But everything has a natural cause – and effect. Glaciers created the lateral moraines that border Moraine Park, Horseshoe Park, Upper Beaver Meadows and the Kawuneeche Valley, to name some of the biggest examples. But these shrinking glaciers (there are still a few in Rocky) are like fingers raking wet sand, creating many of the gullies and narrow canyons in these mountains over 10s of millions of years. These small canyons provide shelter for many species of animals and create microcosms of waterfalls and foliage not found in the blaring sun of Park’s mountaintops. Rocky Mountain National Park's majesty, breathtaking rock formations and views will look quite different in the future as time marches on. What will glaciers leave in their wake during the next ice age, perhaps 10 thousand years from now? We can count ourselves incredibly lucky to be living in this particular time of the geologic history of Rocky.  Barb Boyer Buck is the managing editor of HIKE ROCKY magazine. She is a professional journalist, photographer, editor and playwright. In 2014 and 2015, she wrote and directed two original plays about Estes Park and Rocky Mountain National Park, to honor the Park’s 100th anniversary. Barb lives in Estes Park with her cat, Percy. This piece of original content was made possible by Affinity Massage and Wellness, The Country Market of Estes Park and Images of Rocky Mountain National Park.

story by Chadd Drott, Chadd's Walking With Wildlife The best time to visit Rocky Mountain National Park depends on the purpose of your visit. From backcountry skiing on fresh powder to a beautiful summer day on the summit of Longs Peak, Rocky has something for everyone. However, if you are visiting for the sole purpose of spotting wildlife, there are two times in the year that are best. I recommend coming out during the middle two weeks of September for the fall colors and the peak of the elk rut. However, my recommendation for viewing the most amount of wildlife, and to witness the miracle of life, would be the first two weeks of June. It's baby season in the Park! Visitors may think of calving season as an unlikely time to spot wildlife, assuming that mothers will be hiding their babies in attempt to keep them safe from predators. However, the situation is quite to the contrary. Mothers must come out to eat in order to produce the milk to feed their young and many newborns start following their mothers to feed just a few weeks after being born. This is the best time of year to see many species with their babies. Many animals will have given birth in Rocky in the weeks prior to your visit and others will be calving during your visit. This time of year offers the best time to see many species with their babies when they are the youngest. These are the animals you will most likely see with their young in early summer in the national park. Rocky is best known for Rocky Mountain elk. Elk drop their young starting in late May, continuing through the first half of June. Most young are born in the cover of thick, dark timber outcroppings or on steep hillsides that are close to timberline. Newborns are able to stand up within twenty minutes of being born, and can walk and run within two weeks. Babies lay by themselves in tall grass under the cover of trees. They will lay still on the ground, motionless and with no scent. These two adaptations are their only line of defense from being discovered by a predator. When nursing, the mother will stay a few yards away and the calf will come to her. After nursing, the calf will move off a distance and drop back down. The mother will spend as much time away from her calf as possible the first week to two weeks. Calves are born around 35 pounds and will weigh roughly 63 pounds by the end of the two weeks, at which time the mother brings the calf from the cover of trees and reunites with her herd and their new calves. Elk will spend the next two months nursing their young until they are fully weaned. Even though youngsters will be weaned by month two, they will retain their spots for another four months. Calves will stay with their mothers for the first year and then dissolve into the rest of the herd as the mother moves into the forest to have another round of young.  Mule deer twins and their mother in Rocky/ photo by Dave Rusk Mule deer twins and their mother in Rocky/ photo by Dave Rusk Similar to elk, Mule deer also have babies in May and June. The fawns are born with spots and are also scentless. They use some of the same tactics as elk do, birthing in dense forests with optimal cover. Because deer fawns are so small, mule deer use another tried and true tactic to help ensure their fawns' survival: they choose extremely steep inclines high up in the dark timber where it is hard to traverse. This helps keep wandering predators away from the fawns and lowers of the chance of them stumbling upon one. Deer fawns and elk calves are born with spotted fur. The spots break up their body's outline while it is lying on the ground. In dense forests, the sun peeks through the branches and dapples the forest ground. As the sun passes across the little one's body, it creates a light image on the fur, giving the illusion of grass dancing in the wind. It's the perfect camouflage from the peering eye of a curious predator. If the predator can't smell it, see it or hear it, then it becomes almost impossible to find. Unlike moose, deer and elk cannot close their nostrils to hold their breath, so hiding in water from predators is not an option. Rocky's Shiras moose could be seen as the sole member to a unique family of semi-aquatic mammals, but actually they are just the largest members of the Cervidae (deer) family. Moose deliver around the same time period as elk, but a little earlier: most of their young are definitely dropped in the month of May. Unlike mule deer fawns and elk calves, baby moose are not born with spots. Instead, newborns have a milk chocolate brown coat and are not born scentless. However, moose calves have their own unique adaptations for survival. Moose are able to stand up and have steady legs within the first couple of hours of birth. And within three days of birth, they become faster than even Usain Bolt (known as the fastest human on earth). That's right, moose calves run faster than humans by day three, topping out at speeds in excess of 30 miles per hour. Their front legs are taller than their back ones, which gives moose calves the torque to accelerate extremely fast. If all else fails, they are able to swim more than 10 miles per hour by day two and will retreat with mom into the water if they are unable to outrun a predator. While sightings of deer, elk and moose offspring are relatively common, count yourself quite lucky if you see any of the following animals with their babies in Rocky Mountain National Park. The measures taken by Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep to protect their young from predators are nothing short of harrowing. Although not quite as amazing as the mountain goats' defense tactic of having young on the side of a sheer vertical cliff, bighorn sheep still choose steep and rocky terrain to help guard their young from predators. In fact, although many species would prey upon a baby lamb if given the chance, bighorns in Rocky have narrowed that down to two predators because ewes take their lambs into steep canyons and high up on rocky cliffs near alpine meadows to raise them. The two major predators of bighorn sheep might surprise you. Mountain lions are perfectly adapted to run lambs down over rocky terrain and take full advantage of any of those opportunities during birthing season. The other main predator of lambs is the apex air-superiority predator, the Golden eagle. Lambs are actively hunted by eagles during the first couple weeks of life through their first year. After that, they tend to weigh enough that eagles choose to go after the next year's young. Coyote pups are born after a short, 63-day gestation period, earlier then the deer family’s fawns and calves. Coyotes tend to be born in the beginning of April and start to venture out of the den by the end of May, making early June the perfect time to see puppies outside of a den site. The hardest part about seeing these little ones is that coyotes are very good at keeping their den sites well-hidden from the prying eyes of predators. Some years, coyotes have been seen denning in the middle of one or more of Rocky's large parks. This presents the best opportunity at seeing baby coyotes in Rocky. Unfortunately, life is hard for both predator and prey in the wild, and when a den site is discovered by a number of species the pups may be killed for either food or to eliminate the threat of them growing up and becoming one of the Park's top predators. Bears, foxes, wolverines and eagles will kill pups as a food source. Elk, deer and moose will trample pups to help ensure future generations of their own young will survive. This was unfortunately the case with one famous coyote den last year that was discovered by a few cow elk; eight of the nine pups were killed by trampling and the remaining pup was moved to a new location by the parents. The least likely of our most recognized species in Rocky to be seen with their young is the American black bear. But black bears are not the rarest of large animals in the park to be seen with cubs, that would be the mountain lion. Bear sows unsuspectingly give birth to their young inside of their dens in late January or very early February. It is not until the sow wakes from her torpid sleep in March or April that she discovers her offspring. She will not emerge with her cubs until mid-April. Due to the extremely low population within Park boundaries and the fact sows like to keep their cubs hidden, seeing a bear with cubs in RMNP is a rarity for sure. However, like many things in our beautiful Park, it is never impossible to see them. Look for bears with cubs in lower lying areas around 9000' such as Ponderosa pine forests or large groves of Aspen. These trees give the cubs the best opportunity to climb up if needed when trouble arrives. This elevation also provides the best opportunity for food sources within the park. Both flora and fauna are plentiful in the high montane region. Unlike many other species who have young year after year, black bears are a biannual species. They give birth only once every other year and raise their cubs for almost two years before chasing them off during the cub's second June. Cubs will end up spending seventeen months with their mother, learning everything that they need to for surviving on their own. Mothers chase off their cubs in early spring once the weather is best, to help give the cubs the most time available to figure out life on their own before the harsh winter hits. Although it seems cruel, believe it or not, this is their mother's last loving gift to the cubs. She has waited until the days and nights stay warm and food is plentiful to find and forage upon. Most cubs are experts at survival by this time anyway. As long as they can avoid other larger bears and people, they should do just fine living a bear's life until it is their turn to reproduce, and add to the survival of their species. A few months later the mother will mate again in fall and be ready to start all over again come January! Editor's Note: As a reminder, wild animals with young are extremely dangerous to humans. Rocky Mountain National Park's wildlife viewing guidelines should be adhered to in all situations if possible. VIPs (Volunteers in Parks) often patrol wildlife sightings in the Park to help keep visitors at a safe distance, but ultimately it is your responsibility to know the dangers and mitigate for them.  Chadd is a 6th generation Coloradan and has been studying and working with wildlife for over 25 years. With an expansive knowledge of the natural world around him, Chadd’s expertise has been solicited for wildlife consultations around the nation. Each summer, he runs the premier wildlife tour in RMNP - voted #1 on Trip Advisor. Learn more about his tours at Chaddswww.com This piece of original content, included in the current issue of HIKE ROCKY magazine, was made possible by Longhorn Liquor, Scot's Sporting Goods and Tahosa Coffee House.

How to avoid an attack, and what to do if you are mauled by a bear story by Chadd Drott, Chadd's Walking With Wildlife photos by Barb Boyer Buck The most important aspect of bear safety, or any predator safety for that matter, is to remember there is not one guaranteed way to avoid nor survive an attack. There are steps you can take to do your best to avoid an attack but nothing, including the advice of a self- proclaimed expert, is foolproof. The first and obvious step is to keep a healthy and safe distance. You should not be able to make out any facial features of the bear and that includes its golden muzzle. (About 100+ yards should give you plenty of space to not harass, stress or startle the bear, while still giving you an opportunity to enjoy nature at its best.) Unfortunately, that is not always possible. Maybe you come around a bend and startle a bear or maybe you are someone who walks with headphones on and didn't hear or see the bear until it was too late. At this point THE GAME IS ON and there is no way to wish your way out of the situation. You need to focus on mitigating the issue at hand. A scared bear is an unpredictable bear. One thing is for sure, the bear definitely has flight on its mind more than fight about 99% of the time. Remember, the bear is just as scared of you as you are of it. In the same way that you don't want to fight the bear, it does not want to fight you either. In the wild, an injury almost certainly spells death for an animal. Bears are super intelligent creatures and definitely understand the risks involved with fighting you. A bear only attacks once it feels its flight option is no longer a viable means of survival, which works to YOUR advantage. You need to slow down and realize giving the bear “an out” will result in a non-confrontational outcome most of the time. There are always exceptions to that rule, and I would say if you startle a bear within 20 yards or spook a sow with cubs, you are that exception to the rule. At this point, an attack may be imminent. To avoid an attack, it is best to not panic! Screaming, running, flailing, and crying are all bad reactions when coming face-to-face with a bear. Just as dangerous but often not considered during an encounter is looking like a predator. Crouching, hiding behind something or slowly tiptoeing are all character behaviors of a predator, and a mother sow will not take kindly to those reactions. The best option is to stop and stand tall in place. Give you and the bear a second or two to work out what each other are. Next, speak CALMLY in a soft but stern voice to the bear. Make sure you break eye contact but don't look completely away from the bear. It is important to let it know you are definitely aware of where it is at all times. Look off center of the bear, maybe at a tree a few feet left or right of it, just avoid looking directly at the bear as it may take that as a challenge. In my opinion, I do not think waving your hands above your head is a good idea, I know that is what many say to do, and you are more than welcome to use whatever advice you trust when in this situation. I think large movements are never a good idea when in a standoff. I personally would raise my hands directly above my elbows and have my elbows at shoulder height to appear as boxy and (large) as possible. Slowly but smoothly continue to move backward, never showing your back to the animal. I also like to slightly pivot my body with one shoulder slightly toward the bear so the animal is a little less threatened with me squaring off with it. If the bear starts to approach, continue speaking in a soft and stern voice and add emphasis to your words while slightly raising your volume. Continue to move back until the bear runs off, then move away in the opposite direction to try to work around the area in a wide, sweeping circle. If the bear charges, it is almost always a bluff charge where the animal stops short or turns away at the last second. Most of the time, American black bears tend to run away after their one successful bluff charge. Stand your ground during the charge, do not turn to run, and do your best not to panic. Yell in a deep loud voice and position yourself into a fight posture. It sounds scary and foolish, but if the bear is going to attack, you have one option and one option only: FIGHT BACK! DO NOT UNDER ANY CIRCUMSTANCE PLAY DEAD with an American black bear. Keep your hands in a boxing position as this will cover your face and neck during the initial take down. This also leaves your hands free to punch, slap, gouge and claw your way to hopefully, freedom. If you put your hands by your side before the bear tackles you, your arms will be pinned by your side under the bear, and it will have what is known as full guard and free range of your face and neck. It is important to concentrate on fighting back with kicks and punches, while at the same time protect your neck by keeping your chin tucked against your chest. Fight with everything you have and don't stop until the bear gives up. The bear will fight and only give up for two reasons: either you win, (and by win I mean you survive long enough for the bear to think it is now safe enough to run away) or the bear wins and well, it doesn't much matter from there. I continually hear people say play dead during a bear attack, and that is only true for brown and grizzly bears in North America. This is mainly because fighting back is fatal; you stand a higher statical chance, mind you not by much, if you play dead. American black bears are a species that will make sure you are down for the count if you give up, so you need to fight back if you are attacked. Remember this adage in the case of a confrontation with one of North America's four major bear species: If it's black, fight back! If it is brown, lay down! And if it is white, say goodnight! Obviously there is some satire in there, but it is not wrong. Now before I leave you, I want to reiterate a few things. I did not sugarcoat this because if it happens to you, I want to read about how you survived against the odds and are still around to talk about it. However, the chances you will be attacked by a bear in the woods is extremely rare! In fact, they actually have a statistics on it: there is a 0.02% chance (or, one in 2.1 million) of being attacked by a bear in any national park. If you camp at a roadside campground, your chances then decrease to one in 26.6 million. And finally, if you account for Rocky Mountain National Park only having about 20 bears, you now have a better chance of being struck by lightning on a sunny day than you do of being attacked by an American black bear on your next hike in Rocky. I looked it up: there is one in 15,300 chance of being struck by lighting during a storm, but you have a one in 1.22 million chance of being struck by lightning with the weather phenomenon called “a bolt from the blue.” Just some food for thought on your next hiking adventure.  Chadd Drott is a 6th generation Coloradan and has been studying and working with wildlife for over 25 years. With an expansive knowledge of the natural world around him, Chadd’s expertise has been solicited for wildlife consultations around the nation. Each summer, he runs the premier wildlife tour in RMNP - voted #1 on Trip Advisor. Learn more about his tours at Chaddswww.com This piece of orignial content was made possible by Snowy Peaks Winery, Heidi Riedesel, Realtor and Estes Park Health.

story and photos by Scott Rashid, director of the Colorado Avian Research and Rehabilitation Institute For many of us, the term “snowbirds” has two meanings. One is the older folks that live in Colorado for the summer and head south to winter in Arizona, Texas, or Florida. The other meaning is the birds that winter in Colorado. Snowbirds (the avian kind) that are found in the mountains can be different species than those found in the foothills and plains. For example, each winter, Clark's Nutcrackers, Pine Grosbeaks, and brown- capped, black and Gray-crowned Rosy-finches move from the alpine tundra of Rocky and sub-alpine and to winter in and around Estes Park, Aspen, Vail, and other mountain towns. Other mountain species including Steller's Jays, Mountain Chickadees, Brown Creepers, Red-breasted Nuthatches, Cassin's Finches, and Pine Siskins may simply move from the mountains which at roughly 7,000-9,000 feet and move to winter at about 5,000 feet. There are species that come down from the north to spend the winter in Colorado every year. These include Rough-legged Hawks, Herring Gulls, Lesser Black- backed Gulls, Ring-billed Gulls, Tree Sparrows, Northern Shrikes, Harris's Sparrows, and Lapland Longspurs. Other species including Evening Grosbeaks, Bohemian Waxwings, Snow Buntings, Red Crossbills, Common Redpolls, Purple Finches, and Snowy Owls, are seen only during some winters. When these species are seen they are frequently in large numbers, in multiple locations throughout the state. When those species are seen in large numbers, it is often considered an eruption. Eruptions occur due to a reduction in resources on their nesting grounds, forcing the birds to move to areas that will sustain them throughout the winter. A few years ago, there was an eruption of Common Redpolls in Colorado. These tiny finches (about the size of a goldfinch or Pine Siskin) came down from the far north and spent the winter here. It seemed like everyone who had a bird feeder was seeing redpolls. That was a wonderful sight. The interesting part of these eruption years is that it is seldom, if ever an eruption of more then a single species. This year happens to be an exception to the rule as Bohemian Waxwings, Cassin's Finches and Evening Grosbeaks are being seen in large numbers. The Bohemian Waxwings (the larger cousin to the Cedar Waxwings, which are seen in Colorado in the spring and summer) are being seen in areas where fruit bearing trees and shrubs have high concentrations of apples, and berries that the birds are feasting upon. There are areas where you can find well over 100 birds in a flock. The birds feel safer in large numbers as it is easier for them to stay protected from predators and find enough food to feed the members of the flock, as there is always a bird or two searching for the next resource heavy location. Evening Grosbeaks and Cassin's Finches are also being seen in large numbers this winter. These finches are being seen at bird feeders feasting upon sunflower seeds. They are easily attracted to your yard if you have large platform feeders filled with sunflower seed where the birds can feed in large numbers. Finches including Evening Grosbeaks and Cassin's Finches feel safer in large numbers and are being seen in flocks of 60 and 70 individuals at a time. As spring approaches (March and April) the waxwings will move north to nest in Canada, Some of the Evening Grosbeaks and Cassin's Finches may remain in Colorado to nest, but many of them will move north into Wyoming and Montana to nest. As spring approaches, many of our summer residents, both avian and human will begin returning to Estes Park to spend the summer.  Artist, researcher, bird rehabilitator, author, and director of a nonprofit are only a few things that describe Scott Rashid. Scott has been painting, illustrating and writing about birds for over 30 years. In 2011, Scott created the Colorado Avian Research and Rehabilitation Institute in Estes Park. In 2019, Scott located and documented the first Boreal Owl nest in the history of Rocky Mountain National Park in Colorado. Scott has written and published five books and several papers on a variety of avian species. More information is available on his website: http://www.carriep.org/ The piece of original content was made possible by New Roots Real Estate and the Country Market of Estes Park.

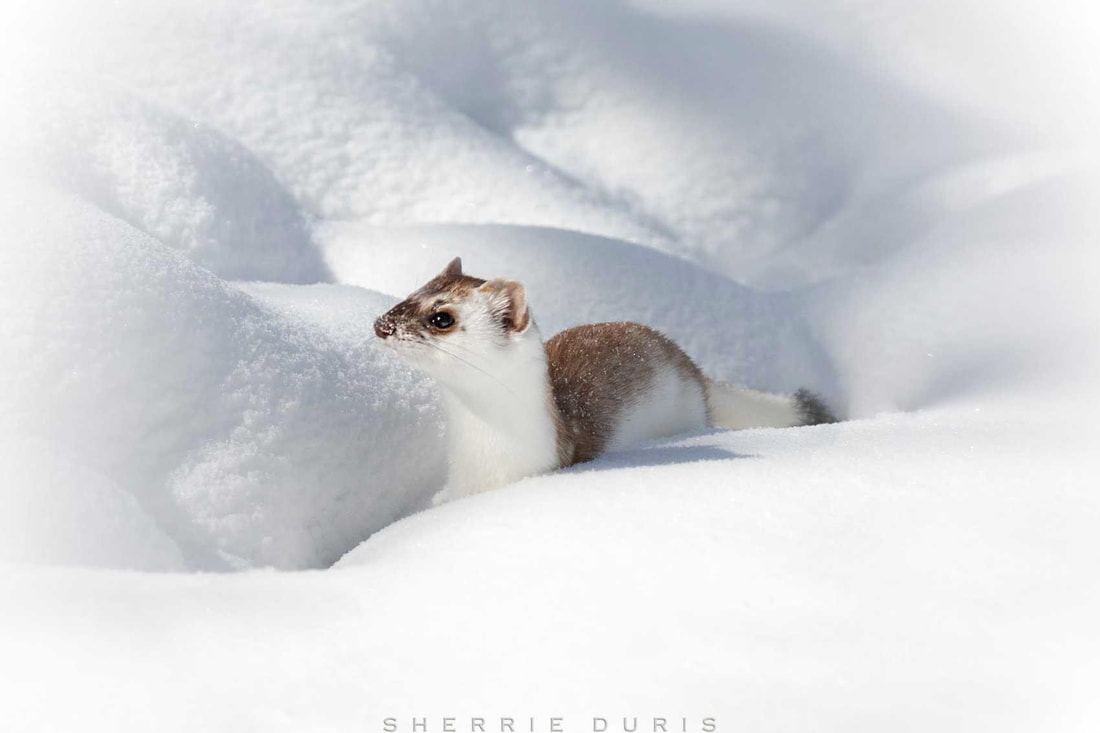

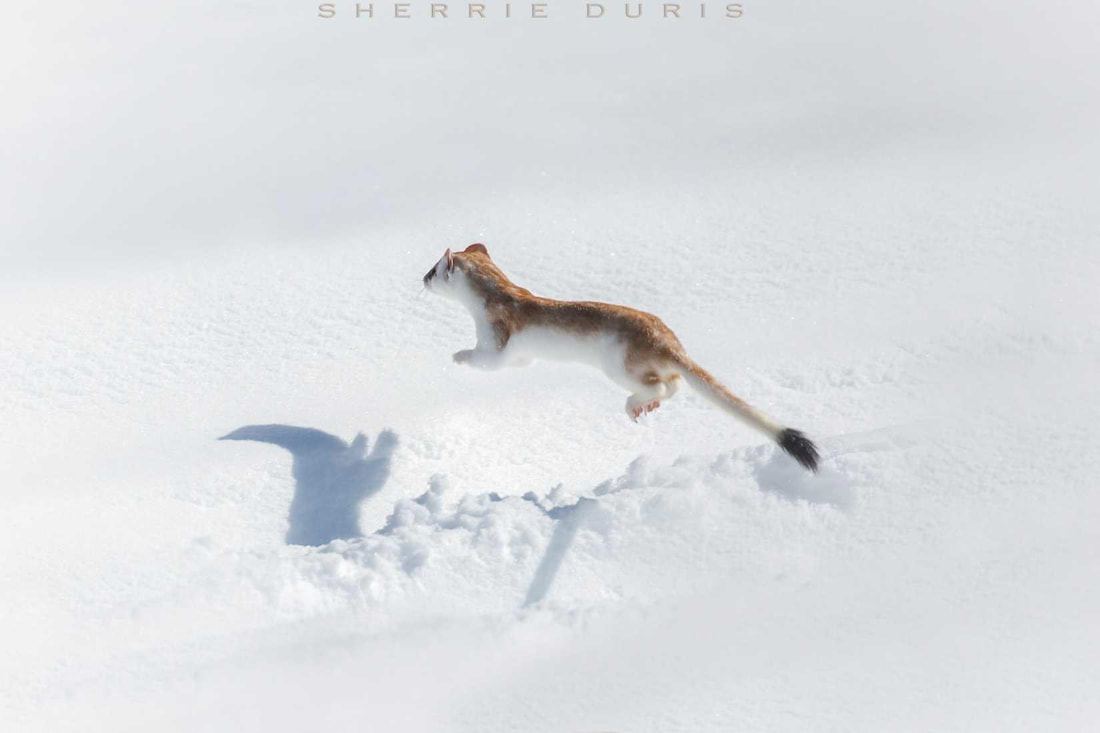

story by Chadd Drott, Walking With Wildlife with Chad photos by Sherrie Durris, Sherrie Duris Photography In the wonderful, wild, and at many times, whimsical world of the weasel, life is only lived in the fast lane. Mustelidae are a family of carnivorous weasels including otters, ferrets, badgers, wolverines, martens, fishers, ermines and mink. Like all members of this family, the long-tailed weasel (Mustela frenata) lives a speedy life. Now, before I get too far into their mysterious lifestyle, I think it would be best for me to tell you exactly what a long-tailed weasel is and what makes them so unique! Although there are many mammals around the world that belong to the Mustelidae family, there are only three recognized weasel species in North America: the long-tailed weasel, the short-tailed weasel, and the least weasel. Colorado has two of the three species with established populations. Both the long-tailed and the short-tailed weasels call this state home, and both are abundant in Rocky Mountain National Park. Out of the three, the long-tailed weasel is the largest and the most abundant in the United States. They are one of many mammalian species that exhibit sexual dimorphism. This means the males are either larger or more colorful than the females (males are larger in this case). Males can measure up to 38 inches from the tip of the nose to the tip of the tail. They can also weigh as much as nine ounces. Females are slightly smaller coming in at 30.5 in. and weighing a maximum of 7.2 oz. If you remember this little rhyme, it will help you to decipher whether the species you are looking at is a predator or prey. “Eyes in front, you're meant to hunt; eyes on the side, you're meant to hide.” This helps you determine that the long-tailed weasel is in fact a predatory species. Throughout Colorado long-tail weasels experience a biannual molt, the changing of their fur color, twice a year. In the summer months, they are brown from nose to about the first 80 percent of their tails along the dorsal line of the body. The underbelly is either white or a slight yellow creme color from the chin to the inguinal region. Their eyes are jet black and face forward on the top of the head. The tip of its tail is also pure black. In winter, their whole body turns a brilliant pure white color, excluding their beady eyes and their black-tipped tail. Why do they molt? When do they molt? And even more curiously, how do they molt? As a tour guide in RMNP, clients are often surprised to learn that long-tailed weasels molt. “Molt? I thought only birds molted?” Although they are not completely wrong as every bird species on the planet does undergo some sort of molt at some point in their life (most birds molt yearly and biannually much like our featured creature), there are many other species around the world that undergo a molt as well. The long-tailed weasel is of them. Molting takes place for two major reasons. The first and most obvious reason is to camouflage from potential prey. Having to capture every meal they eat, predators need every advantage they can get. The second, and the most often over-looked reason, is camouflage from predators. Another great rule to remember when observing wildlife in their natural environment is if you are not the biggest predator, then you are not the only predator. These weasels have to avoid coming face- to-face with coyotes, foxes, bobcats, Canadian lynx, eagles, some owl species, and then, of course, their larger cousins such as badgers, wolverines, and fishers. Molting takes place in mammals because of a chemical/hormonal release in the pituitary gland located at the base of the brain. Similar to our own pituitary gland, both serve many of the same functions which is understandable since we both share the mammalian classification. However, although we shed skin and hair cells, we certainly do not molt in the same fashion as many of our mammalian cousins. The timing of the long-tailed weasel's molt has always been what fascinates me the most. For a species that does not keep time or follow a calendar, they sure do hit the mark right on time year after year. Most people think the molt takes place because it gets cold in the winter and hot in the summer. The actual reasons are due to astronomy and an internal biological clock. Yes, that’s right, the stars literally have to align to allow this little guy to change color. Actually, it’s not really the stars, it’s our planet. Twice a year, in the spring and in autumn, the Earth reaches the right tilt on its axis and is the right distance from the sun resulting in the perfect amount of daylight to prompt molting. During the equinoxes, the weasel's brain starts receiving the exact amount of ultraviolet light from the sun to trigger the autonomic nervous system (ANS). The ANS can be broken down into three more subdivisions; however, for the purpose of this article, we will only stick with the sympathetic nervous system (SNS). The SNS controls how one’s body reacts to every experience and is the main controller of an animal's flight-or-fight reaction. These reactions are dictated by the chemicals and hormones released by the pituitary gland. before the temperatures get too hot or too cold. The pituitary gland is triggered, and the molt begins. After three or four weeks, the molt is complete. Because the amount of daylight is consistent year after year, the molting animal does not run the same risk of hypothermia or hypothermia that it would if it relied on varying annual temperatures. Now that we understand why the long-tailed weasel changes color, I think this is the point where I should bring up that during winter, this species becomes the most misidentified weasel in North America. So, this is the perfect opportunity to explain the differences between the long-tailed weasel and the short-tailed weasel. Long-tail weasels have a couple of classic names, but none that are used today, and there is a good chance you have not heard of any of them. Although the short-tailed weasel is not the most abundant weasel in North America, they are a “Holarctic” species (a species that is found around the circumference of the Earth but only in the northern hemisphere). Short-tailed weasels are also called ermines or stoats. There are a couple ways to identify the two species apart. The first and main way is in the name. The long-tails sport a tail that is about half their body length while the ermine, or short-tails, have a tail that is only a third of their length and not as bushy. Both have the exact same coloring on the tail with a black tip at the back. The only other reliable way for someone starting out trying to ID one or both of these elusive animals is during the summer months, when the long-tails lose the fur covering their feet. Their toes become visible during summer molt while the ermines' feet remain furred the entire year. The long-tailed weasel can be found in any environment in Rocky Mountain National Park. They are found in all three ecosystems: high montane, subalpine, and alpine. They are most often seen in and around waterways throughout the park, taking full advantage of the abundant food sources the riparian areas have to offer. They can also be seen on or along the roadways and trails throughout the park and at any elevation along any rocky outcropping. Nowhere is there a spot safe from the ever curious and always hungry weasel. Their behavior changes dramatically with the seasons and temperatures. Like most animals that live a fast life, they spend the vast majority of their lives either sleeping or hunting to maintain their metabolism. Mating is their only other activity, along with females raising their young, known as “kits.” Males spend any free time fighting off other males for territory. It's a simple but harsh life for the little weasels of Rocky Mountain National Park, but their presence in the Park are a sure sign of a healthy ecosystem for hopefully years to come. Oh and one last thing: Barb, the managing editor of this magazine, asked me to throw in as many cool and interesting facts about these little guys as I could. So, here is one more! The Least Weasel, only found in the northern United States and throughout Canada (not Colorado), has the second-strongest bite force “pound for pound” of any other land animal in the world! Only the Tasmanian Devil has a stronger bite. All weasels kill with a single, crushing bite to either the windpipe and jugular or the more-chosen method, a single bite to the back of the spinal cord. BRUTAL! The least weasel comes in at a whopping 8 ounces, yet it has a full bite force of 85 psi! To put that into perspective, a full grown coyote weighs in at 45 lb. and has a full bite force of 88 psi. To put it in to a little more perspective, humans have a full bite force around 150 psi. If we had the jaw of a least weasel, we would be able to bite a femur bone of an adult cow in half, and it would be like biting ice. The weasel actually evolved around its jaw. It stayed small and took after rodents because it would run out of food if it was apex-predator size and had to maintain an equal metabolism. Last food for thought: if the least weasel would grow to similar dimensions as North America's top predator, the cougar, it would be able to consume every single land animal on planet earth, including being able to bring down elephants and rhinos with a single bite. In fact even the Nile crocodile and the salt water crocodile with the strongest top armor plated necks would be able to be bitten through like butter. So next time you look at someone's pet ferret, just remember what could have been.  Chadd is a 6th generation Coloradan and has been studying and working with wildlife for over 25 years. With an expansive knowledge of the natural world around him, Chadd’s expertise has been solicited for wildlife consultations around the nation. Each summer, he runs the premier wildlife tour in RMNP - voted #1 on Trip Advisor. Learn more about his tours at Chaddswww.com. This piece of original content was made possible by Estes Park Health and Scot's Sporting Goods.

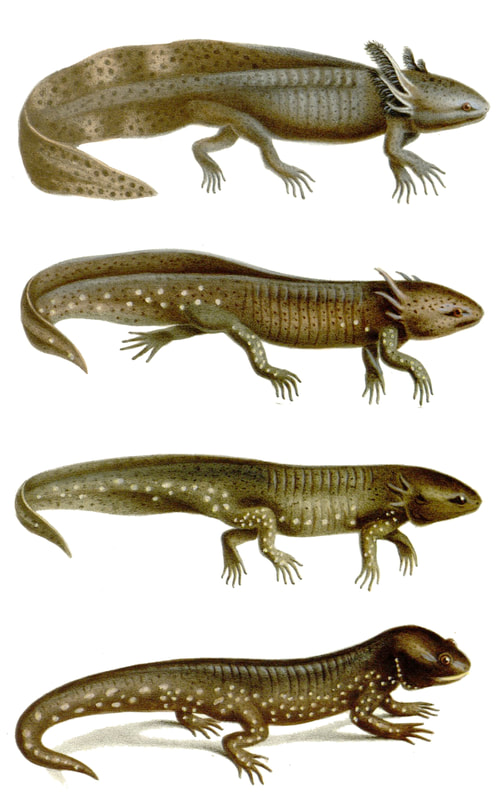

This article is extracted from the current issue of HIKE ROCKY magazine; to learn more about becoming a member to read the entire publication, click here Climate change may be forcing more Western Tiger Salamanders to become terrestrial Photo, video, and story by Barb Boyer Buck, Managing Editor On a beautiful morning in late September, the surface of Lily Lake was still as glass. I walked out onto the fishing platform that extends above the lake and gazed into the water. “What is that?” exclaimed my friend Krissy, pointing to an odd creature just emerging from under a rock to walk along the muddy lakebed. I was stumped. I have studied, lived near, and visited Rocky Mountain National Park for nearly 25 years, and I had never seen such a creature. It was definitely an amphibian and had frilly gills extending from both sides of its head. Suddenly, another one emerged and began walking in another direction to burrow its head into the mud among the grasses. Neither came up for air the entire time we watched them. My group of friends turned to me, quizzical. I was supposed to be the expert, after all; the people I was with were only in town to work for the summer/fall and were brand-new to the area. I spied a group of rangers and some of the Park's trail crew working nearby and asked them to come over. The video accompanying this story shows this rarely-seen denizen of the deep in action. A few rangers were nearby and identified them as Western Tiger Salamanders; they looked exactly like dark-colored axolotls. I had to know more. I spoke with Jonathan Lewis, Wildlife Response Technician and Bear Management, Amphibian, and Avian Programs Lead for RMNP. He explained that sometimes, the tiger salamander stays in this newt-like stage, “with external gills that look like a dragon” for its entire life.  NPS/ROMO photo NPS/ROMO photo “The gills filter the oxygen from the water,” Lewis said, “That way, they don't ever need to come up for air.” The ones who “choose to leave the wetlands” will mature further into the full-grown creature, more easily recognizable as a salamander. But these “mud puppies” can grow up to a foot long and never leave the water. “This is one of the largest salamanders, less than 14 inches long, and one of only four amphibians native to RMNP,” Lewis explained. Although common – “a saturated species,” according to Lewis – they are very rarely seen because they are mostly nocturnal and live most of their lives underground. They hibernate underground, too. “They are ravenous predators, sometimes eating aquatic insects found in the mud, and can even be cannibals” he added. They live a long time, too – “more than 10 years, about 13-14 years in the wild. “Mating season is in the spring, when they congregate to the same pond where they were born,” said Lewis. “Females will lay clusters of up to 10-15 eggs, or even single eggs. When they are born, they look like little tadpoles with legs and gills. They swim in the warmer water; in the shallows. For those who choose to fully mature, that takes about three months. Its tail is very poisonous and even the membrane on its skin is slightly poisonous – do not touch these creatures if you happen to come across one! It’s scientific name is Ambystoma mavortium, a type of a mole salamander, and ranges from southwestern Canada all the way to northern Mexico. Unfortunately, as many other species in RMNP, the Western Tiger Salamander is being affected by climate change. In a study completed in 2005 in Lamar Cave in Yellowstone National Park, Temporal response of the tiger salamander (Ambystoma tigrinum) to 3,000 years of climatic variation , researchers concluded that further warming and drying climate conditions would significantly reduce these “mud puppies” in RMNP. “The Yellowstone study suggests that Rocky Mountain National Park staff and visitors may start seeing fewer paedomorphic and more, larger terrestrial adult tiger salamanders as conditions continue to warm two to five degrees centigrade as predicted in the region of the park based on the two most widely accepted climate models. What this would mean to tiger salamander population numbers, which are currently thought to be stable, or to populations of other park amphibians known to be less well off is still unclear.” (source: https://www.nps.gov/romo/learn/nature/tiger_salamande rs_climate_change.htm ) It was such a thrill to discover an animal I had never seen before, even after studying Rocky for nearly 25 years! There are so many surprises waiting for everyone during explorations of this wonderful national treasure if you take your time, stay quiet and still, and most importantly: leave no trace.  Barb Boyer Buck is the managing editor of HIKE ROCKY magazine. She is a professional journalist, photographer, editor and playwright. In 2014 and 2015, she wrote and directed two original plays about Estes Park and Rocky Mountain National Park, to honor the Park’s 100th anniversary. Barb lives in Estes Park with her cat, Percy. The publication of this piece of local and independent journalism was made possible by The Country of Estes Park and MacGregor Mountain Lodge.

Story and photos by Marlene Borneman Editor's note: this piece is included in the article, "Three of the Best Wildflower Hikes in Rocky," by Marlene Borneman, published in the June/July edition of Hike ROCKY magazine. WEST UTE TRAIL Mileage: 9 miles round-trip (one way 4.5 miles) Elevation gain: 1,038 elevation loss one-way; 1,038 elevation gain round trip Rating: Easy one-way and Moderate round-trip Life Zones: Alpine/subalpine Peak Bloom: July-August The hike begins across from the Alpine Visitor Center (AVC) at 11,796 feet and ends at Milner Pass 10,758 feet smack on the Continental Divide! It is an approximate 23-mile drive from the Beaver Meadows entrance station to the Alpine Visitor Center. From the Grand Lake park entrance, go north on US 34 for 20.2 miles to the AVC. Milner Pass is 4.3 miles west from the AVC on Trail Ridge Road. There are restrooms at the AVC and at Milner Pass. A pleasant way to do this excursion is with a car shuttle making this a one-way trip. This avoids uphill gains and retracing steps. Place a car(s) at the Milner Pass Trailhead. One car brings the driver(s) back up to the AVC to begin the hike. This is one of my choice hikes to view a variety of exquisite alpine and subalpine wildflowers. In addition to wildflowers, marmots, pikas, snowshoe hares, and elk are often seen. Another bonus is spectacular views of the Never Summer Range. I never tire of this hike.  Alpine clover Alpine clover Start hiking by crossing Trail Ridge Road at the AVC parking lot to the obvious trail southwest. The trail crosses the expansive alpine tundra taking in alpine clover, dwarf clover, Parry's clover, blackhead daisy, alpine sunflower, American bistort, mountain dryad, spotted saxifrage, alpine stitchwort, alpine parsley and loads more. In July, the petite elegant snowlover can be abundant and a treasure to find. Cushion plants, champions of the tundra, are at home here boasting their fortitude against the elements. Moss campion, alpine forget-me-not, and alpine phlox are a few of these sturdy plants to be seen on this trail.  Pika Pika There is a short uphill section within the first mile reaching a rocky depression on the left (east) side of the trail. These large rocks shelter pikas and marmots. The pika's favorite food, alpine avens, is plentiful on the tundra. Pikas do not hibernate so they must gather food all summer to store in their hay piles to sustain them in the winter. Just beyond this spot the uncommon gold bloom saxifrage forms a bright gold carpet. I enjoy taking time with these flowers, getting down low with my hand lens to see the tiny golden spots on each petal. Arctic gentians add to the mix anywhere from mid- august through October. Many species of paintbrush flaunt the tundra with various shades of red, magenta and pale yellow. An often overlooked plant on the tundra is sibbaldia. The common name is cloverleaf rose. Sibbaldia has tiny yellow flowers and leaflets that resemble a three-leaf clover. Also often passed by are two ground hugging willows, the alpine willow and snow willow. They often grow side by side. One way to tell them apart is by their leaves. The alpine willow has broad bright green leaves with pointed tips and a deep mid-vein, whereas the snow willow leaves are rounded on the tips with a prominent netted vein pattern. The tiny flowers (catkins) lie within the leaves. Farther on to the east, three pristine tarns create peaceful spots for burnt-orange false dandelion, pinnateleaf daisy, dwarf goldenrod, subalpine daisy, dwarf chiming bell, Whipple's penstemon, starwort, mountain laurel, rose crown and king's crown. In August, start looking for several species of gentians in this area. Arctic gentians add to the mix anywhere from mid- august through October. Many species of paintbrush flaunt the tundra with various shades of red, magenta and pale yellow. After hiking approximately 2.3 miles you come to Forest Canyon Overlook. This marks approximately a halfway mark for the hike. In this area you may see Parry's lousewort, pale agoseris and Coulter's daisy. Heading down, the trail often becomes muddy from melting snow. Striking pink elephanthead fills the moist meadows. Before mid-July you may even find snow along this part of the trail. As the trail levels out, remaining muddy from the snow melting above and the many rivulets of water coming down the steep slopes above, watch for gray angelica, brook saxifrage, alpine speedwell, Hornemann's willowherb, marsh marigold, and globeflower that enjoy this damp habitat to the fullest. A strange appearance in wet areas is the bishops cap. Another find here in late July-August is the fringed grass-of-Parnassus. If you are there at the right time, waves of brilliant yellow come into view with the arrowleaf ragwort. There are a few stream-crossings to negotiate along here, too. As the trail drops farther into subalpine forest, look closely for the tiny plants in the Heath family; one- sided wintergreen, pyrolas, and wood nymphs sheltering under foliage. After 3.8 miles at the signed Mount Ida Trail junction, swing right for approximately 1.0 mile down to Milner Pass. Along the switchbacks, robust masses of heartleaf bittercress show off brilliant white petals. Jacob's ladder, hooked mountain violet, spotted coral root orchid and the more elusive wood nymph grace the forest floor. At this juncture, columbines, bracted alumroot, strawberry blight, and alpine sorrel can also be seen among the crevices. In August, blacktip senecio will be seen in abundance along the stretch of trail following the Poudre Lake shore all the way to the trail head. Take time to look under the flower head and see the black tips on the phyllaries. Purple fringe and paintbrushes are also in the assortment of flowers along Poudre Lake shores down to Milner Pass.  Massive bull elk near Poudre Lake (near Milner Pass). Massive bull elk near Poudre Lake (near Milner Pass).  Marlene has been photographing Colorado's wildflowers while on her hiking and climbing adventures since 1979. Marlene has climbed Colorado's 54 14ers and the 126 USGS named peaks in Rocky. She is the author of Rocky Mountain Wildflowers 2nd Edition, The Best Front Range Wildflower Hikes , and Rocky Mountain Alpine Flowers. The publication of this article was made possible by Rock Creek Pizza of Allenspark and Castle Mountain Lodge of Estes Park, supporting local and independent journalism.

Story and photos by Marlene Borneman Editor's note: the hike to Timber Lake is just one of three of the best wildflower hikes in Rocky Mountain National Park included in the June/July issue of HIKE ROCKY magazine. Become a member today to read about the other two! TIMBER LAKE Mileage: 10.9 miles Round Trip Elevation gain: 2,000 feet Rating: Moderate - Strenuous Life Zones: Montane, subalpine Peak Bloom: July – mid- August COMPLETE TRAIL PROFILE This is terrific wildflower hike on the west side of the park through a broad range of habitats. The East Troublesome fire forever changed the landscape in some areas of the park's west side, however this trail was spared. Be aware, moose, elk and deer frequent this trail. The hike begins at the Timber Lake Trailhead approximately 32 miles from the Beaver Meadows entrance and 10 miles from the Grand Lake entrance. There are restrooms at the trailhead. A well-defined trail leads through a small meadow for a short distance. The trail then heads southeast through both dry and moist lodgepole pine and aspen forest where small-leaf pussy toes, Parry's milkvetch, showy locoweed, Richardson's and wild geranium, cinquefoil, and kinnikinnick are scattered. The tiny one-sided wintergreen, green-flowered wintergreen and pink pyrola are found here too under the shady canopies.  Heartleaf arnicas thickly fill in the hillsides with their bright yellow faces. In the moist forest you may see a flower that has a rather peculiar appearance. That is the bishops cap, also known as five-star miterwort. This flower often goes unnoticed even though it grows in clusters of a dozen plants or more. This is likely because it is very tiny and green in color. I take a hand lens just to gaze upon its amazing art work. Soon a bridge crosses Beaver Creek where the trail becomes steeper and switchbacks up southeast through a conifer forest. Plants that prefer a drier habitat can be found here such as pinedrops, white hawkweed, and Fendler's ragwort.  Landslide on the Timber Lake Trail. Landslide on the Timber Lake Trail. Within two miles there is a large landslide area that can be difficult to cross. There are large boulders and large downed trees to climb over and around. The stretch is about 70 feet wide before connecting back to the established trail.  Parry's Primrose Parry's Primrose There are several small tributary streams and many seeps along this trail which provide the perfect spot for Hornemann's willowherb, twinflower, Parry's primrose and American alpine speedwell. Fringed grass of Parnassuss is the big prize to see in these wet shady areas. The hike continues along the lower slopes of Jackstraw mountain where mountain death camas, sickletop lousewort, fern leaf lousewort, red paintbrush, and fireweed prosper. Heading southeast the view soon opens out along a boggy area where white and green bog orchids maybe found along with star gentian, fringed gentian and elephanthead. After a short steep climb the trail comes to a beautiful meadow where subalpine daisies and saffron ragwort gather in masses. Heading southeast the trail steepens following the outlet stream to the lake. Tall chiming bells and heart-leaf bittercress fill in around the flowing waters. The meadows surrounding Timber Lake lakes outlet stream are very marshy. The soggy ground is loaded with marsh marigolds, globeflowers, and alpine laurel, also called mountain bog laurel. Timber Lake makes an idyllic setting for lunch taking in the view of the west side of Mount Ida. Marmots are part of the scenery at the lake so take care not to leave your pack unattended.  Marlene has been photographing Colorado's wildflowers while on her hiking and climbing adventures since 1979. Marlene has climbed Colorado's 54 14ers and the 126 USGS named peaks in Rocky. She is the author of Rocky Mountain Wildflowers 2nd Ed, The Best Front Range Wildflower Hikes, and Rocky Mountain Alpine Flowers. Click here to purchase Marlene's books Story and photos by Marlene M. Borneman Editor's note: the hike to Bluebird Lake in Wild Basin is just one of three of the best wildflower hikes in Rocky Mountain National Park included in the June/July issue of HIKE ROCKY magazine. Become a member today to read about the other two! Whether you are looking to broaden your skills to identify flowers, find a rare plant, photograph a unique flower, or just to soak in the sheer beauty of an eye- popping field of color, wildflower hikes are a gratifying adventure for both body and mind. Whatever trail you decide to explore, simply delight in this world filled with wildflowers! What makes a good wildflower hike? Trails that weave through life zones provide many opportunities to view and identify a wide range of wildflowers. I feel so fortunate that Rocky Mountain National Park encompasses four life zones: foothills, montane, subalpine, and alpine where over a thousand species of wildflowers call home. I look for trails with a diversity of habitats that will in turn provide a diversity of flower species. Hike in peak bloom. “Peak bloom” refers to the most likely time to view a wide range of flowers with the greatest numbers in bloom. Keep in mind that there will always be early and late blooming flowers before and after peak bloom. There are seasons within seasons so expected appearances sometimes vary by weeks from year to year. Nature strictly controls blooming times with current temperatures and moisture levels. These variables fluctuate year to year making the ever-changing blooming times new and challenging. They determine a generous season or a sparing one. I want wildflowers hikes that offer a “wow” factor, making for a memorable moment whether it is a rare wildflower or an endless multi-colored meadow. An extra bonus are the many pollinators that visit these flowers. Interactions between wildflowers and pollinators are a wonder to observe. As with any hike, be prepared for ever-changing weather in the mountains. Dogs are not allowed on the trails. Plan to pay an entrance fee and have a timed- entry pass depending on your start time. Protecting Colorado's flora is an essential element to the enjoyment. Never pick wildflowers! Do not attempt to transplant wild plants. Be aware it is illegal to collect plants in the national parks and national forests. Please be mindful of the restoration signs in designated areas. Al Schneider, creator of www.swcoloradowildflowers.com, says it best: “Admire them in the wild and let them live.” Don't forget a hand lens and a wildflower guidebook to enhance your enjoyment. BLUEBIRD LAKE Mileage: 12.8 miles Elevation gain: 2,478 feet Rating: Strenuous Life Zones: Montane, subalpine, and alpine Peak Bloom: Late July-August COMPLETE TRAIL PROFILE This is spectacular hike in Wild Basin takes you from a moist montane forest to alpine terrain. Waterfalls, fast flowing streams, and a small pond are features along the way with the finale of a stunning alpine lake surrounded by high peaks on the Continental Divide—graced by magnificent wildflowers. Begin at the Wild Basin trailhead following the Thunder Lake trail. Along the first section, mariposa lily, wild geranium, sulphur flower, mountain harebell, wild rose shrub, Solomon's seal, Nuttall's larkspur, pinedrop, penstemon, and many more species line the fringes of the trail.  White Monkshood White Monkshood Following North St. Vrain Creek, Copeland Falls, Calypso Cascades are passed before Ouzel Falls is reached. Sections close to the creek are home for monkshood and cutleaf coneflower lining both the south and north sides of the trail. You may even spot the uncommon white monkshood. Delicate small plants can be found along here, too: wood nymph, pyrolas, spotted coralroot orchid, violets, one-sided wintergreen and pipsissewa. As Ouzel Falls is reached, cross a substantial bridge. Along the falls see sprinkles of Parry's primrose, columbines, cowparsnip, diamond-leaf saxifrage, and lovage.  Columbian Monkshood Columbian Monkshood At 3.4 miles you will come to the junction with the Bluebird Lake trail. The trail takes a southwest direction and within 1.2 miles arrives at the junction with Ouzel Lake trail. Stay on the Bluebird Lake trail following a stretch along a ridge. The 1979 Ouzel fire is still evident here with old snags and small tree growth but lots of other vegetation has filled in. There are many red elderberry shrubs, wild raspberry, mountain strawberry and twin berry shrubs along this stretch. Soon you will look down on Chickadee Pond. It is worth going down to the pond watching your steps over wet, loose rocks. Chickadee Pond hosts yellow pond lilies and in the shallow water near the shoreline buckbean is noticeable. Just 1.75 miles and right under 1,000 feet of elevation gain to go. In late-July, mid-August get ready for a breathtaking display of wildflowers ahead. The high meadows below Bluebird Lake explode with a mass of brilliant hues of white, yellow, golds, reds, pinks, purples, and blues. Many shades of paintbrushes mixed in with elephanthead, subalpine daisy, American bistort, hairy arnica, nodding ragwort, arrowleaf ragwort, Colorado Blue Columbine steal the scene. The trail climbs steeply here with switchbacks coming to a short narrow canyon. Take your time watching for small cairns that will lead to the top with the overpowering view of the lake! Mount Copeland, Ouzel Peak, and Mahana Peak provide a grand backdrop. Arctic gentian scatter around the lake in mid-august- September. My eye always seems to catch more wildflower sightings on the way down so keep alert.  Marlene has been photographing Colorado's wildflowers while on her hiking and climbing adventures since 1974. Marlene has climbed Colorado's 54 14ers and the 126 USGS named peaks in Rocky. She is the author of Rocky Mountain Wildflowers 2nd Ed, The Best Front Range Wildflower Hikes, and Rocky Mountain Alpine Flowers. |

Categories

All

|

© Copyright 2025 Barefoot Publications, All Rights Reserved