|

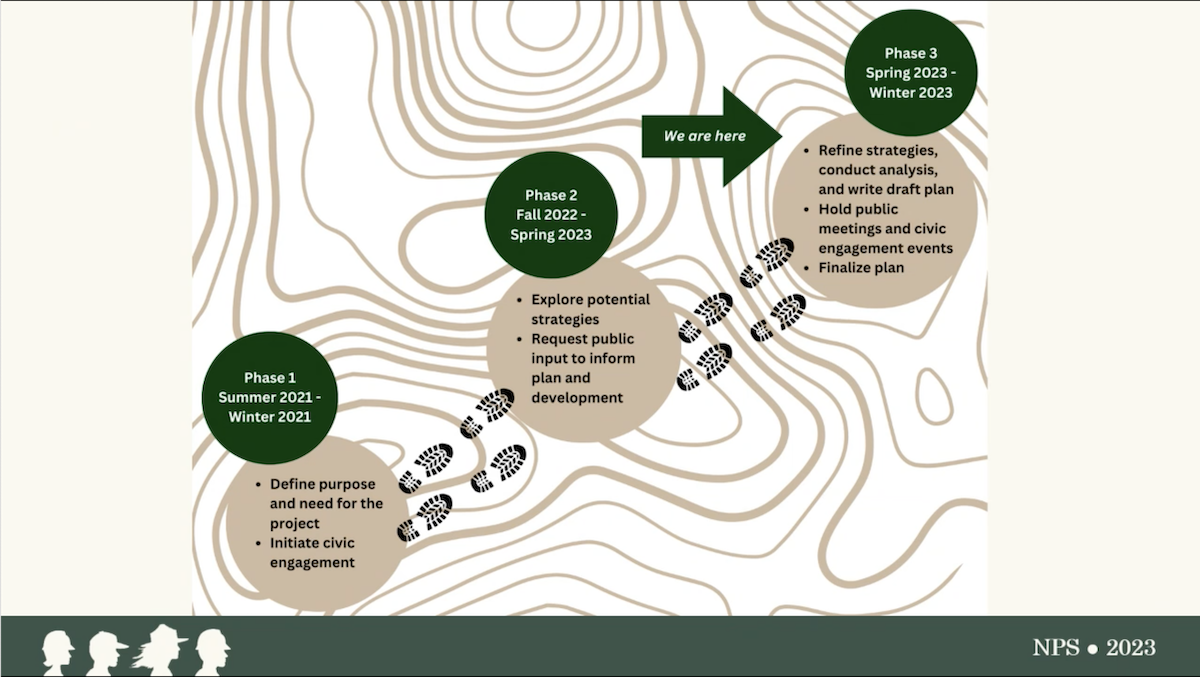

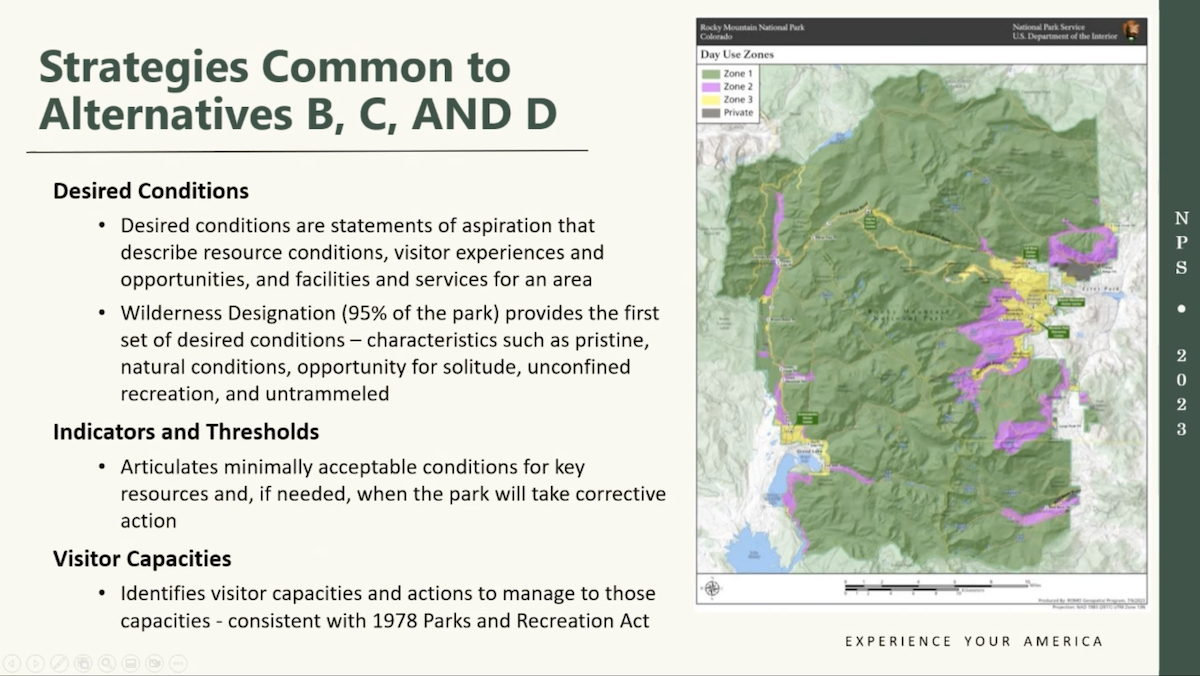

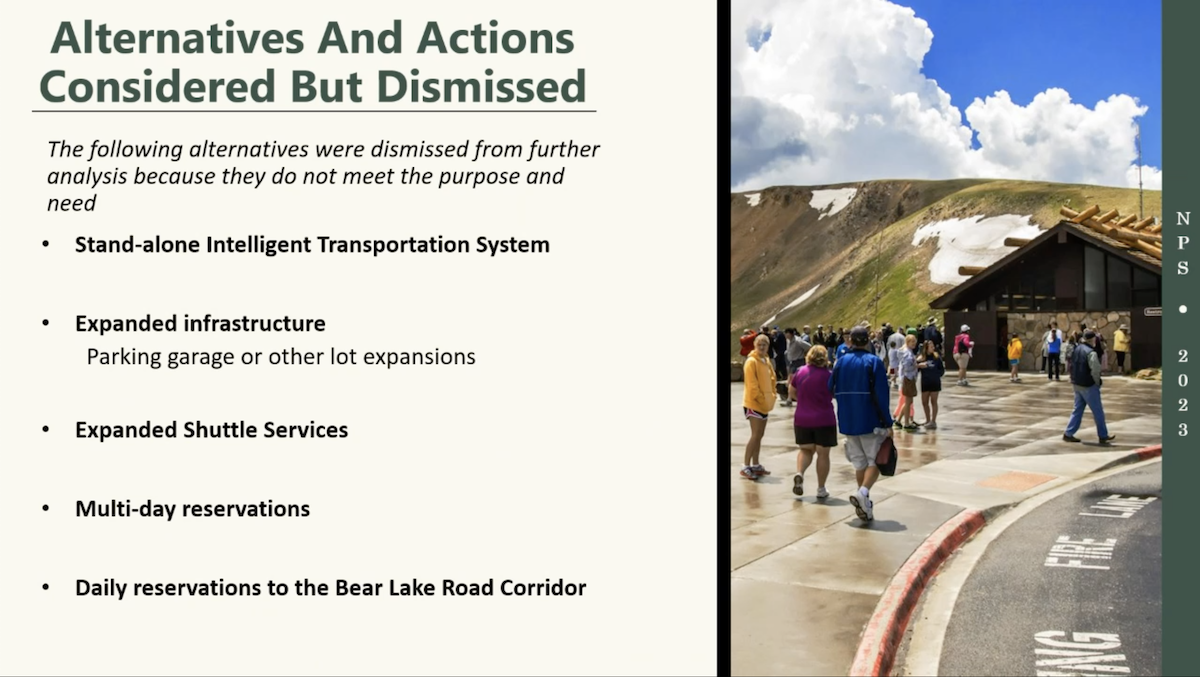

The slides below is information presented during the Virtual Public Meeting on the Environmental Assessment for the Long-Range Day Use Visitor Access Plan, on November 8, 2023. The intent of the presentation is to provide opportunities to learn more about the purpose of the project, key ideas, issues of concern, desired conditions for the park’s long-term day use visitor access, potential management strategies, ask questions of NPS staff and get information on how to provide formal written comments through the Planning, Environment and Public Comment (PEPC) website. You are invited to learn more about the park's Day Use Visitor Access Plan and Environmental Assessment (EA) by viewing a StoryMap and reviewing the EA at https://parkplanning.nps.gov/ROMO_DUVAS.

2 Comments

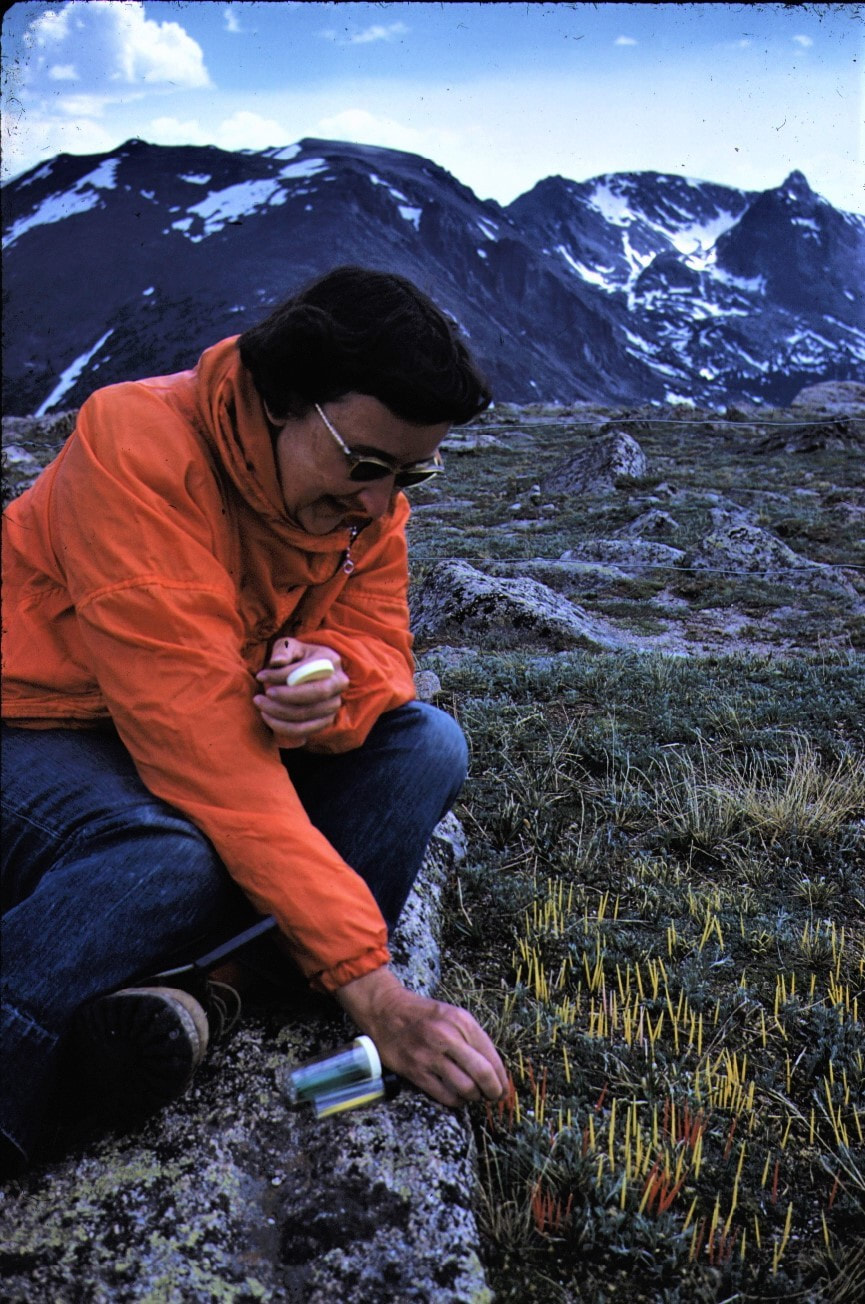

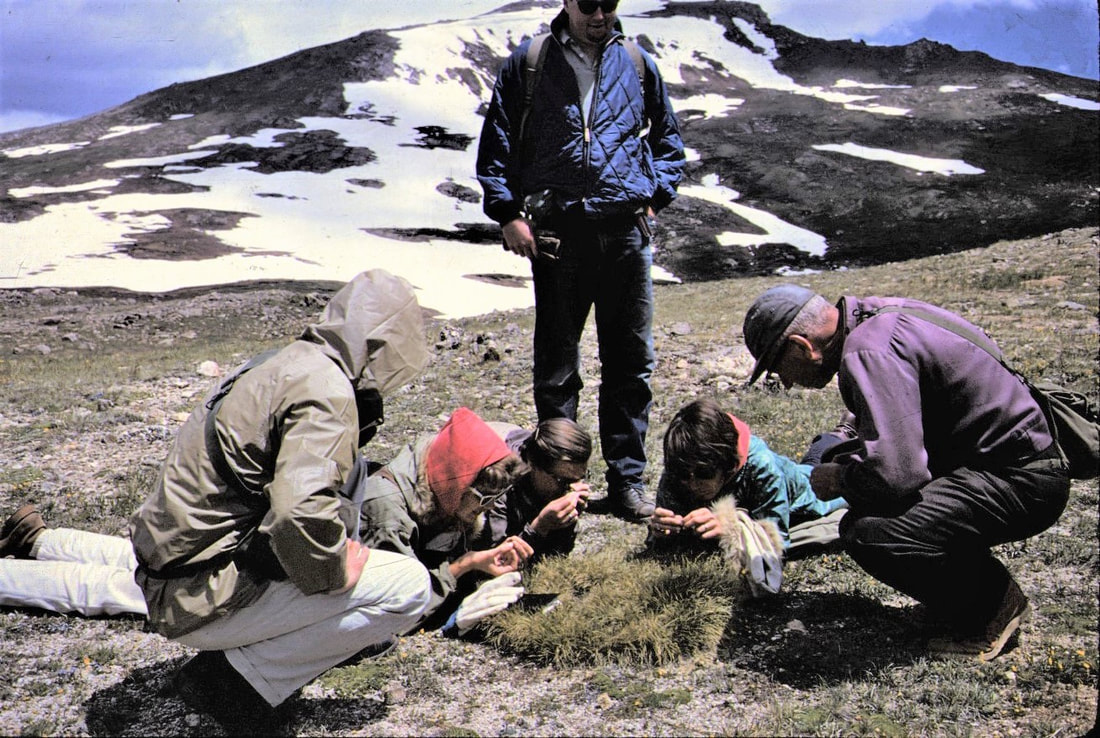

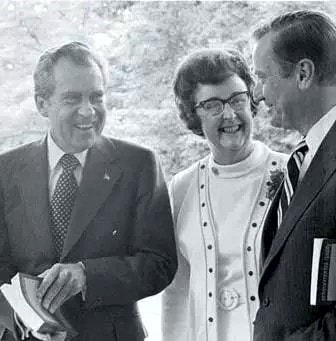

It is illegal to walk on the tundra in Rocky Mountain National Park at Fall River Pass, Gore Range, Rock Cut, Lava Cliffs and Forest Canyon Overlook. For reasons which will be explained, concentrated visitor use atthese areas poses a proven threat to the delicate tundra. HOWEVER, other areas of the alpine tundra, which is one-third of the Park's terrain, can be traversed upon; albeit, very lightly. Walking is not the preferred way to study this ecosystem up close. “Belly Science” – first developed by Bettie Willard – puts you on the tundra face down, spreading your weight across plants that have survived the harshest of climates for hundreds of years. The ground is surprisingly soft and supple, even furry in places where fine white hairs grow over leaves and petals, protecting each tiny plant from hurricane- force winds and near-freezing overnight temperatures. Fragrant, floral, clean and airy: the smells of the tundra are reserved for those who have the audacity to stick their noses into it. (see Rocky Mountain National Park’s policy on tundra use) This is a world where the smallest of organisms create a community of symbiotic relationships, each plant working with each pollinator to help feed its neighbors and expand vegetation above treeline, a world where roots run deep and plants stay short, with impossibly- bright blooms spreading out to hug the horizon, all the way up to the vertical end of the world. Respecting this world is paramount and understanding its legacy is just as profound. Bettie Willard's National Park work Bettie Willard always dreamed of being a National Park Service ranger, especially after she attended the Yosemite Field School in the summer of 1948. For that entire summer, she and other attendees lived in tents and worked in the wilds of Yosemite National Park, studying nature up close. Graduates from the field school – 16 men and four women – were then interviewed by the National Park Service, but Bettie's dream of being a ranger was dashed: “Don't you know? We don't hire women for those positions,” she was told. It didn't matter that she had just graduated from Stanford University with a degree in biological sciences or that she already had a lifetime of experience guiding through the wilds near Mammoth Lakes, California, where she spent summers with her parents. It only mattered that she was female. Willard dealt with mid-Century norms for women throughout the rest of her life but this environmentalist was not daunted. She had made an influential friend: Dorr Yeager, Rocky Mountain National Park's first naturalist and author of the “Bob Flame, RMNP Ranger” novels. Over the next several years, he asked around and found only four National Parks that were willing to hire women; one of these, Lava Beds National Monument (est. 1925), finally hired her as a ranger for the summer of 1952. The following summer, she was a ranger at Crater Lake National Park (est. 1902). When asked later in life how she got along as the only female ranger in those Parks at that time, she said that she did a lot of observation at first, finding out which rangers worked in which department or niche. Willard filled neglected niches, thus preventing stepped- on toes (and egos) of the more established, male rangers. She prided herself on complementing – not competing with – what the other rangers were doing. Between her undergraduate studies and this life goal achieved, Willard attended UC Berkeley to become a teacher. She taught in Salinas, then Oakland and finally general studies at Tulelake High School, located in California near the Oregon border. It was considered a rural school and eligible for the newly formed Ford Foundation educational grants. In 1954, she was awarded a $4,600 scholarship which “was enough for her to go to Europe for 14 months to study vegetation on the high mountains. She wanted to study the vegetation in the Alps, in Scandinavia and other places in Europe,” explained Leanne Benton, co-instructor for the Rocky Mountain Conservancy's “Bettie” Course: “Tundra Pioneer: the life and legacy of Bettie Willard,” held on July 20. Benton is a long-time Rocky Mountain National Park volunteer and taught this course with Cheri Yost, the current Park Planner for Rocky. While in Europe, Willard attended a conference of 2,000 international botanists in Paris and made valuable connections which led to several field trips in Switzerland to study alpine plants. “She also met a woman, Ruth Ashton Nelson, who was a Colorado botanist and had already published a book on the plants of the Rocky Mountain National Park,” Benton said. By the time Bettie was finished with her European studies and work, she knew she wanted to go to grad school and study American alpine plants, specifically to compare those with the plants she had studied in Europe. But first Willard had to fulfil the requirements of the scholarship by teaching two more years at Tulelake. In 1957, she enrolled in the University of Colorado at Boulder to study ecology. “Ecology really came into its own in the late 1890s and women were getting ecology degrees since the 1910s,” Cheri Yost explained. “But most women ecologists were either working with their more famous husbands, like Edith Clements, or they were teachers. They really weren't doing their own independent research.” But by the late 1950s Willard was doing just that, under the instruction of noted arctic and alpine ecologist John W. Marr. Willard wanted to study “plant sociology” (like she did in Europe) on the alpine tundra in Rocky. She established a plot at Rock Cut in 1958 that was 10 square meters large (current pipe fencing at Rock Cut includes her original plot). The same trail that she used through this area can still be seen, standing as a testament to the long recovery time for disturbed tundra. A second plot was established at the newly-built Forest Canyon Overlook. Her studies at several spots on Rocky's tundra led to the completion of her master's and then her doctorate, from the University of Colorado. “What she was noticing was that visitor use was having a huge impact on the tundra,” Yost said. Willard needed to convince Park managers that visitors were having an impact on this delicate area and that something had to be done about it. She thought the trails on the tundra should be paved and hardened, “if you pave a trail, people will stay on them,” was her argument. Next, she wanted Park managers to “stop the craziness in the backcountry,” because there were no rules about camping in the backcountry in Rocky. And finally, Willard wanted people to become stewards of the tundra through education and experience. She accomplished these goals by utilizing the skills, hard work and diplomacy that she had always applied working in the heretofore “man's world” of the National Parks. Visitor impact was proven through vast data sets – collected by Willard and others - that tracked alpine environments. Mission 66 (which was launched in the mid-1950s) provided the infrastructure funds to pave the areas she recommended, and her experience with backcountry “craziness” in her research both above and below treeline led to the establishment of backcountry camping permits in the early 1970s. Willard started teaching the first field seminar program in Rocky Mountain National Park, through the Rocky Mountain Nature Association (now the RM Conservancy). “She taught the alpine field seminar for many, many years in the Park,” said Yost. Willard was also instrumental in getting alpine rangers in Rocky to teach the public about the tundra and in the placement of signage and educational displays in the Alpine Visitor Center and other places. For 40 years, Willard came back to study her alpine plots every summer in Rocky, funded in part by the Department of Defense (since the country was still at war in various arenas). “She took photos of her plots, put toothpicks down to mark the individual plants, and tracked those plants for the entire time she worked in Rocky,” Yost said. Today, Jackson Maldonado, Alpine Community Science Intern, is continuing Bettie's work in much the same way. This summer was the kick-off of a continuing community science project that will encompass two programs: one with trained volunteers doing surveys at Willard's original plots and the other program designed for community members. It will teach them about climate change effects on the tundra, and the phenology (or life-cycle) of tundra plants and include an excursion onto the tundra to identify its wildflowers. “If we can get a solid data set that builds off of what Bettie started, we can really track the impacts climate change is having on the tundra,” Maldonado said. He spent much of the summer working with Park employees to create the parameters, logistics and study scope of the project, which will kick off its first year of serious study in the summer of 2024. Bettie's "experiments in ecology" But Bettie Willard's story doesn’t end with her important conservation work in Rocky. She wrote Land Above the Trees: Guide to American Alpine Tundra with Ann Zwinger in 1971. “This book was instrumental while I was learning about the tundra as an RMNP ranger,” said Leanne Benton. Moss campion, a cushion plant, is one of the “champions” of the tundra, Benton said, growing only about ½ inch by the time it's five years old. “It doesn't really start to bloom unless it's about 10 years old and by the time it's 20-25 years old it's about 7 inches wide and blooming profusely. “Think about what a grinding footstep can do to a plant like this,” Benton said. After Willard achieved her doctorate, she stayed in Boulder and helped to found the Thorne Ecological Institute. In 1965, she became its Executive Director, in 1967, she was its vice president; and, in 1970, president. “Thorne's mission was to help people understand the relationships in the environment and develop a personal concern for the Earth,” explained Cheri Yost. “While Willard was at Thorne, it put her at the forefront of many environmental partnerships.” Willard went on to form and/or serve with numerous environmental organizations throughout the state, excelling at collaboration. “In 1966, she created what she called 'the experiment in ecology,' ” explained Yost. “She really believed that all of these conversations were a three-legged stool: engineering, economics and the environment. If you could not get these three concerns to talk to each other, you are not going to be successful stewards of health and society.” Working with the mining industry along with environmental concerns in Colorado, Willard created “a safe space to work out differences so meaningful and lasting agreements could be made,” Yost explained. “We fostered abundant measures of openness, objectivity, willingness to tell all, an ability to listen and believe but to question until Truth comes forward,” Willard said of this time in her life. Working for the Federal Government In 1969, Congress passed the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), which codified Willard's “experiment in ecology,” on a national level. Its mission was to bring every new environmental policy in front of everyone who would be affected by it. The next year, President Richard M. Nixon appointed Willard to the President's Council of Environmental Quality (CEQ). She was the first woman to serve on this council, which existed to educate everybody in the country on NEPA. “Most of the environmental laws on the books today were put in under the Nixon Administration,” explained Yost. Willard received many letters of congratulations for her service with the federal government, but nearly every one of them contained some back-handed compliments, essentially: “pretty good – for a woman.” For the rest of her life, Willard went on to champion common-sense environmental laws in Colorado and nationwide. For example, said Benton, there were several things that Willard did to help mitigate the environmental issues with the Alaskan Pipeline during its NEPA process. “She made about 15 trips up to Alaska during that time to look at the route planned for the pipeline and was instrumental in getting the pipeline raised above areas of permafrost (so it wouldn't melt) – and raised high enough to not interfere with caribou migration.” Willard was not against development. “She worked for Nixon, she was a Republican,” Yost said. “She was the head of the Colorado Olympic Committee in 1970 when Denver was awarded the 1976 Winter Olympics. She didn't have any concerns about the Olympics itself, she had a problem with the necessary, uncontrolled building that was going to happen next to it.” Ultimately, voters in Colorado voted against holding the 1976 Winter Olympics in the Colorado Rockies, making it the only state to ever refuse the offer. Bettie returns to Colorado to educate on environmental issues in the state Bettie Willard returned to Boulder after the change of administration and after a few years, “she was approached by the Colorado School of Mines, one of the foremost mining schools internationally, to set up a department of environmental sciences, looking at how to mitigate the effects of mining,” Benton explained. When she was interviewing for the job, she asked the president of the board: 'How do you feel about working with a woman?' She accepted, but only after being assured that anyone exhibiting chauvinistic behaviors would not be tolerated at the school. She developed the brand-new department and created 28 classes, many of which she taught herself. Thirty- two students graduated with the Minor degree she designed, but still, she didn't feel equal to her fellow professors. “She felt some type of discrimination,” Benton said. In 1982, she took a leave of absence: two years without pay. Nevertheless, she traveled, cross-country skied, taught, and wrote books (many of which are some of Benton's most treasured possessions). When it came time to return to the School of Mines, she just didn't want to and “resigned” in 1984. For the rest of her life until she was no longer able, Bettie Willard wrote books, taught, served on groups and committees and taught seminars. “She taught seminars here (for the Rocky Mountain Conservancy) until 1996,” said Benton. “I was able to take a course from her in 1995,” Benton recalled. This experience really cemented Benton's commitment to Rocky. “She was a very gifted teacher,” Benton said. Bettie Willard passed away from Alzheimer's disease in 2003. You can continue Bettie's legacy at Rocky! Jackson Maldonado is looking for some people to practice Belly Science with him next summer, through his Alpine Community Science projects. You can reach him with questions at [email protected]) Like Willard, Maldonado dreams of working for the National Park Service after he graduates. “I would love to make Parks more accessible, everyone deserves to be in green space, to experience nature, safely.” He admires Bettie Willard very much. “The work that she accomplished locally, regionally and nationally positively impacted so many people and the environment.” (Maldonado's views do not necessarily reflect the goals and ideas of the National Park Service.) Like Bettie, Leanne Benton grew up in California. In college, she took a summer Park Ranger job at Rocky; “It was a life-changing summer – I loved the work and the Park. For four more summers I worked as a seasonal Park Ranger on the west side. I met my husband one of those summers who was also a Park Ranger.” After years of working as a full-time Park Ranger for several NPS units, Benton returned to Rocky to manage the Alpine Visitor Center for eleven years. She continues to volunteer with Rocky.  “In Land Above the Trees (1972), Bettie Willard and Ann Zwinger brought together most of what was known about alpine tundra in the U.S., including Bettie's research, and presented it in a book that was understandable for a wide audience,” Benton said. “The book was a huge success. The information so poetically presented in the book illuminated the fascinating adaptations of the plants and animals for survival in the alpine world. Land Above the Trees was THE BOOK that all the park rangers read to learn about alpine ecology so we could effectively communicate with the public. This book continues to be relevant today. The results of Bettie's research and recommendations also laid the foundation for how Park Managers protect the park's tundra, while also allowing public enjoyment of the tundra. Bettie also recommended the importance of education in protecting the tundra.” Benton wants you to remember that while traveling on the tundra, move like a herd of elk, not a line of people. Step on stones or gravel where possible and if there is a trail, use it. Cheri Yost has spent most of her NPS career translating science, which is how she was introduced to the remarkable legacy of Dr. Willard. She is currently the Park Planner.  Barb Boyer Buck is the managing editor of HIKE ROCKY magazine. She is a professional journalist, photographer, editor and playwright. In 2014 and 2015, she wrote and directed two original plays about Isabella Bird and Rocky Mountain National Park, to honor the Park’s 100th anniversary. Barb lives in Estes Park with her cat, Percy. story, photos and video by Barb Boyer Buck Driving up to Estes Park from the Front Range, you travel on roads that were cut through dense layers of basement rock, pushed up from the ground in what looks like a violent fashion. The sight humbles me; I feel quite small, even though this happened millions of years ago. I have to remind myself these rocks are stable enough to support roads that carry four million people to Rocky Mountain National Park each year. The majestic Rocky Mountains that come into view as you dip down into Estes Park look like timeless unchanging sentinels of this mountain valley. But in reality, they are constantly evolving. “There are about seven different plates floating around on the skin of the mantel of the Earth,“ explained Roy Dearen, retired geophysicist and environmental geologist who now lives in Estes Park. “Kind of like a skin on an onion, they are thin and less dense than the mantel below them so they float at a very slow speed, about the speed of your fingernails growing. The Pacific plate and the North American plate are pushing against each other in opposite directions. That's how the ancestral Rockies were formed. The tops of these mountains, at one time, were at least 20,000 feet above sea level.” Roy was born and grew up in Texas; he moved to Colorado in 1975. In 1981, he earned a degree in geology from the University of Colorado at Boulder. He has worked for American Copper & Nickel as a geophysicist, as a seismic interpreter for oil and gas exploration and supervised clean-up operations at the Rocky Flats Nuclear Weapons Plant in the mid-1990s. But I suspect it's his experience as a third and fifth grade teacher at Lyons Elementary School that makes him such a great person to interview on this subject. He makes geology accessible and easy to understand. Roy was kind enough to meet me to discuss the rocks of the Rocky Mountains, specifically those in Rocky Mountain National Park. He shared a geology presentation he gives while conducting tours of Rocky. At a small pull-out in Horseshoe Park just before Sheep Lakes, Roy encourages everyone he takes on this tour to turn toward where Longs Peak sits. Then, he explains the geologic history of the Park, from 90 million years ago until the present. Words are not adequate to put this information into perspective so in the video below, the entire presentation is recreated. But the only way to really experience the unique geology of Rocky is in person. The rocks of the Rocky Mountains are products of erosion and displacement, pulled inexorably downward by gravity. On a tour of the Bear Lake Corridor early this week, Roy showed me some of the more unique rock formations of the area. Of particular interest was a stretched pebble conglomerate: an interesting boulder that collected large pebbles as it was formed, the pressure of the metamorphic process elongating the pebbles in a distinct direction. We were also on the hunt for gneiss (pronounced “nice”). These ancient rocks were formed deep in the Earth, from granite heated to the consistency of toothpaste and squeezed through the cracks in the harder schist layers. Retreating glaciers after the last ice age tumbled the rocks, rounding them in the same process a rock- tumbling machine does. In the large, peaceful parks within Rocky, these round rocks look like they had been placed there by a landscape designer. But everything has a natural cause – and effect. Glaciers created the lateral moraines that border Moraine Park, Horseshoe Park, Upper Beaver Meadows and the Kawuneeche Valley, to name some of the biggest examples. But these shrinking glaciers (there are still a few in Rocky) are like fingers raking wet sand, creating many of the gullies and narrow canyons in these mountains over 10s of millions of years. These small canyons provide shelter for many species of animals and create microcosms of waterfalls and foliage not found in the blaring sun of Park’s mountaintops. Rocky Mountain National Park's majesty, breathtaking rock formations and views will look quite different in the future as time marches on. What will glaciers leave in their wake during the next ice age, perhaps 10 thousand years from now? We can count ourselves incredibly lucky to be living in this particular time of the geologic history of Rocky.  Barb Boyer Buck is the managing editor of HIKE ROCKY magazine. She is a professional journalist, photographer, editor and playwright. In 2014 and 2015, she wrote and directed two original plays about Estes Park and Rocky Mountain National Park, to honor the Park’s 100th anniversary. Barb lives in Estes Park with her cat, Percy. This piece of original content was made possible by Affinity Massage and Wellness, The Country Market of Estes Park and Images of Rocky Mountain National Park.

story, photos and video by Murray Selleck, HIKE ROCKY magazine's gear reviewer Editor’s note: HIKE ROCKY magazine receives no compensation for brands reviewed by Murray Hiking while it’s raining is wonderful. The sound of raindrops hitting the forest floor with soft “tap tap taps” is delightful. The intimacy of nearby birds chirping and singing will have you walking slower while you endeavor to make no sound yourself. Thunder rolls down from the clouds, fills the valleys and echos off the steep rock faces. Aspen leaves quake in the wet breeze letting loose their own shower of raindrops. New spring green becomes even more vibrant, washed clean with the rain. Those who are out hiking in the rain count themselves lucky to experience it. Quiet footsteps on rain-softened trails is such an incredible contrast compared to what most of us have been used to: dusty trails packed hard as stone, every step joint-jarring. Low, heavy clouds flatten ridge tops and drape the forest in a gossamer web of drifting humidity. The terrain appears practically unrecognizable to hikers hungover from decades of drought. Despite some trails becoming slick, despite grand vistas lost in the low hanging vapor, despite the goose-bump-generating temperatures and despite ourselves – a hike in the rain should not be passed up. It should only be seen as an opportunity! This spring my go-to piece of rain gear to get me out no matter what the day brings is the Patagonia Torrentshell 3L Rain Jacket. When you are dry and comfortable any wet weather you encounter is manageable. The alternative to dry and comfortable is wet and miserable and getting caught out unprepared in a rain storm leaves little doubt as to why hiking in the rain gets such a bad rap. Gear up with the Patagonia Torrentshell and embrace a rainy day! Patagonia Torrentshell Features: The Hood Starting at the top, there are two ways to adjust this hood to suit your face and preferences. The very top cord on the back of the hood will pull the sides of the hood back to increase your peripheral vision. There are worse things, but it is aggravating to turn your head to the side only to see the inside of your hood! With this side adjustment you eliminate this possibility and replace it with being able to see everything you’re looking for. The second hood adjustment are two pull cords at the top of either side of the front zipper. These cords will pull the hood down and snug it around your head, ball cap, helmet, or knit hat. These pull cords help you batten down the hatches if your hike turns into a torrent! The visor of the hood is laminated so it won’t flop down over your eyes. And the last feature is that the hood can roll up securely out of the way if no hood is needed at all. The top adjustment cord on the hood has a tiny hook that after you roll the hood up will attach to the loop just inside at the top of the jacket. This keeps the hood rolled up and out of the way. If you have read any of my previous articles or watched some of my video contributions to HIKE ROCKY magazine, you know that I am not a huge fan of hoods. With Patagonia’s Torrentshell, I make an exception! However, hoods do reduce hearing. That fact remains my biggest complaint with hoods. I need to hear all there is to hear – especially when I’m out hiking. I do concede that when Mother Nature has opened up every faucet in the heavens, a hood is a good thing. If a hood keeps one single raindrop from sneaking all the way down my spine, then in this case, I thank Patagonia for the Torrentshell hood!  Waterproof/Breathable The Torrentshell is designed and manufactured with 100% recycled waterproof/breathable face fabric. It achieves Patagonia’s H2No® Performance Standard for a three-layer shell with a PFC-free DWR finish (durable water repellent coating that does not contain perfluorinated chemicals). The three layers are the recycled nylon ripstop face, a polycarbonate PU membrane with 13% biobased content, and a tricot backer and a PFC-free DWR finish. All this tech is to say the Torrentshell will keep you dry with best environmental manufacturing practices in mind. One of the main things I like about the Torrentshell and the reason I purchased one is how light and packable it is. With many more expensive laminated waterproof jackets you get a stiff crunchy feel which can be fine for a winter jacket but if you are looking for a lightweight, easy-to-pack rain jacket, then consider the Torrentshell. Two Pit Zips Pit zips are a mechanical way of opening up the jacket to allow more body generated heat to escape from underneath the jacket. The Torrentshell is waterproof and breathable. There are tons of waterproof/breathable jackets on the market and with no exception you must consider “breathable” with realistic expectations. The Torrentshell is no exception and that is why most manufacturers, including Patagonia, offer pit zips on their rain jackets. Hiking up a steep trail, hiking fast, or even trail running in the rain will generate more body heat than what the jacket can breathe or expel on its own to keep you from over heating. So how do you cope? You open up the pit zips and even zip down the front zipper to release more heat to regulate the microclimate you create under the jacket. The cautionary note with pit zips or unzipping the front collar to vent is the risk of allowing rain, grapple, hail, sleet, or even snow an easy way in. Just be weather and vent savvy. Main Zipper Line I love the fact that Patagonia does not use any velcro to protect the front zipper. Velcro on a zipper line just inhibits the zipper slider from working. Patagonia’s front zipper is touted as snag free and that is pretty much true. The slider may encounter a hiccup or two as you’re using it but that is nothing compared to trying to un-velcro velcro and work the slider up or down as the velcro reattaches itself. A no-velcro, no-snag zipper is a wonderful thing. This front zipper is rain protected by essentially three storm flaps. The main storm flap is on the outside and covers the zipper nicely. The two remaining flaps cover the other side of the zipper line and seal out any wind- driven rain. Nice. Two Pockets The Torrentshell has two very good sized hand pockets with zipper closures. Pockets are not only good for keeping items handy, they can also offer some warmth if you’re not wearing gloves. (I do own a wind shell that has no pockets and there are times I sorely wish it did). You can stuff the entire rain jacket into the left pocket for a handy way to store the jacket when you’re not wearing it. The pocket itself acts as the stuff sack. This pocket has a small loop inside it so you can carabiner the stuffed jacket to your pant loop or daisy chain on your pack. Tip: When you stuff the jacket into the pocket turn the pocket inside out as you stuff the jacket. Cuff and Waist Adjustments Both sleeves have the common velcro closures to help you adjust the length of the sleeve and loosen or tighten the cuff around your wrist. I do have long arms and I like being able to snug the velcro around my wrist to create the correct length of sleeve. I also like the fact that Patagonia has not cut the sleeves too short which is a typical problem for tall and lean hikers. Sleeves that actually run the full length of my arms practically make me giddy! Another common feature is a cord to snug the hem of the jacket around your waist. When the rain and temperatures drop at the same time it is nice to be able to snug the jacket around your waist to keep the body generated heat in the jacket to maintain warmth. The Fit and Year-Round Versatility I am about six feet tall with long legs and arms. Lean and 160 pounds. I wear a size medium in the Torrentshell and it fits perfect. Sleeves that reach a touch beyond my wrists are wonderful. The length of the jacket is not too long which I also like. There is room for additional layers underneath the jacket if I need them. There is no reason why I can’t wear this as a winter shell when the conditions warrant adding even more year-round value to this jacket. Recycled Fabric The Torrentshell is made with recycled nylon. Creating fabric from recycled material may not be newsworthy but in this case it is. Patagonia produced its spring 2023 product line with 89% recycled nylon. Part of their recycled nylon comes from old carpet and old fishing nets. We all need to think more carefully not only about what we buy, but from whom we buy it. Too many “me too” companies out there only pay lip service to our climate crisis and often exaggerate their environmental record. I believe my dollars are well spent when I support Patagonia. Their products are sound and so is their business ethic. Conclusion I like it and recommend it. Now let’s get out and hike… no matter what the day’s weather may bring!  Murray Selleck moved to Colorado in 1978. In the early 80s he split his time working winters in a ski shop in Steamboat Springs and his summers guiding on the Arkansas River. His career in the specialty outdoor industry has continued for over 30 years. Needless to say, he has witnessed decades of change in outdoor equipment and clothing. Steamboat Springs continues to be his home. This piece of original content was made possible by Heidi RIedesel, Realtor; Estes Park Health; and, Snowy Peaks Winery.

story, photos and video by Lincoln Chapman Timber Lake Trail Type: Longer Hike Trailhead: Timber Lake (west side of Rocky) Trailhead Elevation: 9,054' Destination Elevation: 11,088' Total Elevation Gain: 2,060' Total Roundtrip Miles: 10 I'm not sure I've ever hiked a more adequately named trail in recent memory. I'm also fairly certain that I hadn't hiked this unprepared in several years. I hope to do the journey that was Timber Lake Trail justice with this piece. My hope is to explain the dangers, lessons and pitfalls my friend and I found along the path. I really hope this because I wouldn't want anyone else to have to find them for themselves. It was one of those adventures that's only really fun when you live to tell about it. Somebody yell “Timber!” (and mud, and snow, and scat and stones) Timber Lake Trailhead is located on the west side of the Park, closer to Grand Lake than Estes park. The majority of guests enter RMNP through one of the east entrances, meaning they would get the pleasure – and some would say honor – of driving the majority of Trail Ridge Road to get to this trailhead. It's one of the most beautiful drives in thecountry and is built along much of the original Ute trail. It's an amazing drive and a great time sip coffee, hydrate, and eat to fill up before the hike. If you are entering from the Grand lake entrance you will experience less of the views provided by elevation elevation gain. No worries, though – my buddy and I passed at least a dozen buck elk with velvet antlers and two moose on our drive beyond the trailhead toward Grand Lake. The tunes were so good when we first pulled up to the trailhead parking lot, so we drove a bit further and looped around to hear a couple more songs. That action alone admittedly sets the stage for two twenty-somethings vibing too hard and planning too little. We were bangin' our heads out of the window to the Kingston Trio, creating a new boost of false confidence with every song. The first sign we saw at the trailhead indicating how difficult it might be (and the first sign we ignored) read “Active Landslide Area.” I’d heard of some flooding from the Colorado River on trails nearby, so I had a little bit of cautious restraint in the back of my head. However, we should have taken the time to drive to the visitor’s center nearby, to gather any information on the current status of the Timber Lake Trail. This was costly ignorance on my part; but we felt on top of the world coming down from Trail Ridge's apex. We didn't do much other than giggle at the warnings of landslides. The trail runs about 5.3 miles to Timber Lake. It wasn't the lake's timber we needed to worry about, though. We reached our first obstacle at mile marker two: the landslide zone. It ran directly across the path, laid out in a pick-up-sticks style display of fallen trees. It was a bit of a maze just to get through and on top of that. It's remarkable how slick a fallen tree trunk can get. The possibility of a new landslide was our first fear but the wreckage of recent ones were what we had to face. One wrong step and it could, “take our love and take it down.” We maneuvered our way through the logs as slow as we could and high-fived on the other side. “Pfft, all downhill (metaphorically) from here” or something along those lines was certainly spoken. Never taunt the mountains with a sentiment of “pfft,” they will be happy to play that game. We made our way through two miles of lodgepole pine and changed the amount of layers we were wearing about five times in that stretch. It was cold, as early summer has been in the Park. Every half-mile would lead us to taking our jackets off and sipping water, but by the time we were ready to trek again we'd be a bit chilly. The high of the day was predicted to be 48 degrees and it was roughly 7a.m. at this point. The forest is dense on this hike. It feels something like what I refer to as the “woods” back in my home state of Tennessee. “Woods'' are hard to come by in much of the east side of the Park. The west side, in particular Timber Lake Trail, is quite different and mysteriously thick. Mysterious in the sense that you really don't have much of a deep look into what lies, breathes or eats beyond the trail itself. Noises seem to circle, bounce and echo. We hiked with bear spray as I would always suggest. It's much better to be prepared. Wow, there was one thing we did prepare. On one of our water breaks, we sat catching our breath when I heard a growl and he heard a snapping branch. It was just one sound – we just interpreted it differently. We jumped up in Shaggy-and-Scooby- spooked fashion. We grabbed the bear spray and continued to move forward, alert. Again! He heard a big snort and I heard a massive flapping of wings. One noise freaked out both of us, letting our minds get the best of us. We passed what appeared to be scat from a big cat just a half mile or so before, so that certainly wasn't helping. Moments later we both turned our heads in sync, noticing motion in the leaves. There it was. A tiny little grouse hopping along and then flying away. His wings made the loudest echoes, snorts and growls ever, ok? The next mile or so was pleasantly uneventful, but it was steep. We had plenty of water which was a great thing because the third quarter of this hike is very taxing. It's the kind of steep that's gradual, seeming to never end. It’s just enough to wear you out, steadily. As we climbed, we became more aware of our breath. Partly due to the upward slope, and partly because our breath was becoming more and more visible as the air got cold. Snow patches started emerging on our left and our right and then little by little in the middle of the trail. We scampered across a couple six foot long snow piles and felt fine about it. We didn't need snowshoes for any of those, just a burst of energy to get across quickly. Nobody wants wet socks four miles into a 10-mile hike. Snowshoes would've come in handy about a third of a mile away from the lake itself. Like, really handy. It's amazing to me that my friend and I trekked through the snow without proper footgear. The spurts of snow turned into deep accumulation covering the entire trail. We wouldn't have been able to stay on course had it not been for the footprints a brave hiker left before us. We kept our gaze forward and upward toward the peaks, under which was Timber Lake. We followed the path of prints and kept moving forward. The inches of snow that we had begun to master didn't stay at that depth for long. No, to be honest, I'm uncertain just how deep the snowpack went. In one heavy step at one point, I fell straight through down to my waist. I'd really like to believe that was the deepest it got. The timber we had contorted through at mile two was now beneath us, covered in extremely sketchy snow. We decided to take a break from the snow and try something easier. Just left of the footprints, we began stepping from stone to stone. These were large boulders laid out in the most random patterns and heights. We carefully hopped from one to the next, trying to avoid the slick ones. We had to climb a few and use all four limbs. We reached a peak among the stones and saw a portion of the end of the trail, somewhere beyond and through the trees. There weren't any more stones, just trees and snow ahead. We hopped back on to the trail (assuming the footsteps were following it) and powered through the snow. We were in shorts and sneakers trudging through the snow up to our knees. We were so close. We powered through the brush and arrived at Timber Lake. We stood, huffing and puffing and taking it in for several minutes before saying anything. Our adrenaline had been pushed to new extremes on the way, and we both knew what the other was thinking. We shared a moment of silence and appreciation. We hydrated and replenished and laughed at our stupidity. It's easy to laugh at your own stupidity on the other side of it. Thank goodness we made it to the other side unscathed. The lake was still frozen for the most part, and there was tons of snow along the mountain bowl that encapsulates it. The light hit the snow so insanely bright up there, we joked about seeing a new shade of white. The elevation made for wild cloud movements. The clouds literally rushed above the lake; stormy but unthreatening. The shadows moved across the snow and the mountain just as fast. It was magnificent. Magnificently chaotic were the clouds and our experiences that day. We enjoyed the lake for a bit and then prepared to head back. We were more motivated than ever to start the hike back with the most difficult portion knocked out first. Our legs were beginning to feel like Jell-O and our patience was starting to wear thin, so we decided the stones weren't in our best interest on this go. We rushed through the snowpack. We found patches that only took our sopping wet feet an inch or so down into the snow and took other steps that shot our legs down to our knees in the cold. We made it through and the began the now-downhill stretch toward the scary noises. We were at the point of our day where the feeling of being “over it” on a hike was welcomed. After pushing through that stage, the feeling of accomplishment set in. We made it back to the first pile of fallen timber and laughed at how easy it felt compared to the rest. The hike came to an end and we wrung out our socks. It was the ultimate feeling of relief. Take it from me: please do your due diligence and research your hikes before you go. Stop by the visitor’s center and hear from a ranger themselves just what to expect. My buddy and I were lucky to have made it through without a twisted ankle at the very least. We laughed about our stupidity the entire drive back to Estes Park. I'm glad to have experienced the hike; I hope it serves a lesson to myself and to anyone reading as well. Timber Lake trail humbled me, I loved it.  Lincoln Chapman grew up in Nashville, TN, and is 26 years old. He idolized football his entire adolescence, which led him to a small university in Texas where he was finally able to scratch that itch at 22. After school, he started traveling, beginning with Los Angeles, where he started commercial acting and modeling. After a handful of stints in Southern California, he began traveling in his van, chasing any gig and any opportunity. He moved to Estes Park in June, 2022 where he serves wine and is pursuing his writing career. Catch him in the corner of a local watering hole jotting or doodling away on paper. The publicaiton of this piece of original content was made possible by: Ram's Horn Village Resort, Tahaara Mountain Lodge and Twin Owls Steakhouse.

story by Chadd Drott, Chadd's Walking With Wildlife The best time to visit Rocky Mountain National Park depends on the purpose of your visit. From backcountry skiing on fresh powder to a beautiful summer day on the summit of Longs Peak, Rocky has something for everyone. However, if you are visiting for the sole purpose of spotting wildlife, there are two times in the year that are best. I recommend coming out during the middle two weeks of September for the fall colors and the peak of the elk rut. However, my recommendation for viewing the most amount of wildlife, and to witness the miracle of life, would be the first two weeks of June. It's baby season in the Park! Visitors may think of calving season as an unlikely time to spot wildlife, assuming that mothers will be hiding their babies in attempt to keep them safe from predators. However, the situation is quite to the contrary. Mothers must come out to eat in order to produce the milk to feed their young and many newborns start following their mothers to feed just a few weeks after being born. This is the best time of year to see many species with their babies. Many animals will have given birth in Rocky in the weeks prior to your visit and others will be calving during your visit. This time of year offers the best time to see many species with their babies when they are the youngest. These are the animals you will most likely see with their young in early summer in the national park. Rocky is best known for Rocky Mountain elk. Elk drop their young starting in late May, continuing through the first half of June. Most young are born in the cover of thick, dark timber outcroppings or on steep hillsides that are close to timberline. Newborns are able to stand up within twenty minutes of being born, and can walk and run within two weeks. Babies lay by themselves in tall grass under the cover of trees. They will lay still on the ground, motionless and with no scent. These two adaptations are their only line of defense from being discovered by a predator. When nursing, the mother will stay a few yards away and the calf will come to her. After nursing, the calf will move off a distance and drop back down. The mother will spend as much time away from her calf as possible the first week to two weeks. Calves are born around 35 pounds and will weigh roughly 63 pounds by the end of the two weeks, at which time the mother brings the calf from the cover of trees and reunites with her herd and their new calves. Elk will spend the next two months nursing their young until they are fully weaned. Even though youngsters will be weaned by month two, they will retain their spots for another four months. Calves will stay with their mothers for the first year and then dissolve into the rest of the herd as the mother moves into the forest to have another round of young.  Mule deer twins and their mother in Rocky/ photo by Dave Rusk Mule deer twins and their mother in Rocky/ photo by Dave Rusk Similar to elk, Mule deer also have babies in May and June. The fawns are born with spots and are also scentless. They use some of the same tactics as elk do, birthing in dense forests with optimal cover. Because deer fawns are so small, mule deer use another tried and true tactic to help ensure their fawns' survival: they choose extremely steep inclines high up in the dark timber where it is hard to traverse. This helps keep wandering predators away from the fawns and lowers of the chance of them stumbling upon one. Deer fawns and elk calves are born with spotted fur. The spots break up their body's outline while it is lying on the ground. In dense forests, the sun peeks through the branches and dapples the forest ground. As the sun passes across the little one's body, it creates a light image on the fur, giving the illusion of grass dancing in the wind. It's the perfect camouflage from the peering eye of a curious predator. If the predator can't smell it, see it or hear it, then it becomes almost impossible to find. Unlike moose, deer and elk cannot close their nostrils to hold their breath, so hiding in water from predators is not an option. Rocky's Shiras moose could be seen as the sole member to a unique family of semi-aquatic mammals, but actually they are just the largest members of the Cervidae (deer) family. Moose deliver around the same time period as elk, but a little earlier: most of their young are definitely dropped in the month of May. Unlike mule deer fawns and elk calves, baby moose are not born with spots. Instead, newborns have a milk chocolate brown coat and are not born scentless. However, moose calves have their own unique adaptations for survival. Moose are able to stand up and have steady legs within the first couple of hours of birth. And within three days of birth, they become faster than even Usain Bolt (known as the fastest human on earth). That's right, moose calves run faster than humans by day three, topping out at speeds in excess of 30 miles per hour. Their front legs are taller than their back ones, which gives moose calves the torque to accelerate extremely fast. If all else fails, they are able to swim more than 10 miles per hour by day two and will retreat with mom into the water if they are unable to outrun a predator. While sightings of deer, elk and moose offspring are relatively common, count yourself quite lucky if you see any of the following animals with their babies in Rocky Mountain National Park. The measures taken by Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep to protect their young from predators are nothing short of harrowing. Although not quite as amazing as the mountain goats' defense tactic of having young on the side of a sheer vertical cliff, bighorn sheep still choose steep and rocky terrain to help guard their young from predators. In fact, although many species would prey upon a baby lamb if given the chance, bighorns in Rocky have narrowed that down to two predators because ewes take their lambs into steep canyons and high up on rocky cliffs near alpine meadows to raise them. The two major predators of bighorn sheep might surprise you. Mountain lions are perfectly adapted to run lambs down over rocky terrain and take full advantage of any of those opportunities during birthing season. The other main predator of lambs is the apex air-superiority predator, the Golden eagle. Lambs are actively hunted by eagles during the first couple weeks of life through their first year. After that, they tend to weigh enough that eagles choose to go after the next year's young. Coyote pups are born after a short, 63-day gestation period, earlier then the deer family’s fawns and calves. Coyotes tend to be born in the beginning of April and start to venture out of the den by the end of May, making early June the perfect time to see puppies outside of a den site. The hardest part about seeing these little ones is that coyotes are very good at keeping their den sites well-hidden from the prying eyes of predators. Some years, coyotes have been seen denning in the middle of one or more of Rocky's large parks. This presents the best opportunity at seeing baby coyotes in Rocky. Unfortunately, life is hard for both predator and prey in the wild, and when a den site is discovered by a number of species the pups may be killed for either food or to eliminate the threat of them growing up and becoming one of the Park's top predators. Bears, foxes, wolverines and eagles will kill pups as a food source. Elk, deer and moose will trample pups to help ensure future generations of their own young will survive. This was unfortunately the case with one famous coyote den last year that was discovered by a few cow elk; eight of the nine pups were killed by trampling and the remaining pup was moved to a new location by the parents. The least likely of our most recognized species in Rocky to be seen with their young is the American black bear. But black bears are not the rarest of large animals in the park to be seen with cubs, that would be the mountain lion. Bear sows unsuspectingly give birth to their young inside of their dens in late January or very early February. It is not until the sow wakes from her torpid sleep in March or April that she discovers her offspring. She will not emerge with her cubs until mid-April. Due to the extremely low population within Park boundaries and the fact sows like to keep their cubs hidden, seeing a bear with cubs in RMNP is a rarity for sure. However, like many things in our beautiful Park, it is never impossible to see them. Look for bears with cubs in lower lying areas around 9000' such as Ponderosa pine forests or large groves of Aspen. These trees give the cubs the best opportunity to climb up if needed when trouble arrives. This elevation also provides the best opportunity for food sources within the park. Both flora and fauna are plentiful in the high montane region. Unlike many other species who have young year after year, black bears are a biannual species. They give birth only once every other year and raise their cubs for almost two years before chasing them off during the cub's second June. Cubs will end up spending seventeen months with their mother, learning everything that they need to for surviving on their own. Mothers chase off their cubs in early spring once the weather is best, to help give the cubs the most time available to figure out life on their own before the harsh winter hits. Although it seems cruel, believe it or not, this is their mother's last loving gift to the cubs. She has waited until the days and nights stay warm and food is plentiful to find and forage upon. Most cubs are experts at survival by this time anyway. As long as they can avoid other larger bears and people, they should do just fine living a bear's life until it is their turn to reproduce, and add to the survival of their species. A few months later the mother will mate again in fall and be ready to start all over again come January! Editor's Note: As a reminder, wild animals with young are extremely dangerous to humans. Rocky Mountain National Park's wildlife viewing guidelines should be adhered to in all situations if possible. VIPs (Volunteers in Parks) often patrol wildlife sightings in the Park to help keep visitors at a safe distance, but ultimately it is your responsibility to know the dangers and mitigate for them.  Chadd is a 6th generation Coloradan and has been studying and working with wildlife for over 25 years. With an expansive knowledge of the natural world around him, Chadd’s expertise has been solicited for wildlife consultations around the nation. Each summer, he runs the premier wildlife tour in RMNP - voted #1 on Trip Advisor. Learn more about his tours at Chaddswww.com This piece of original content, included in the current issue of HIKE ROCKY magazine, was made possible by Longhorn Liquor, Scot's Sporting Goods and Tahosa Coffee House.

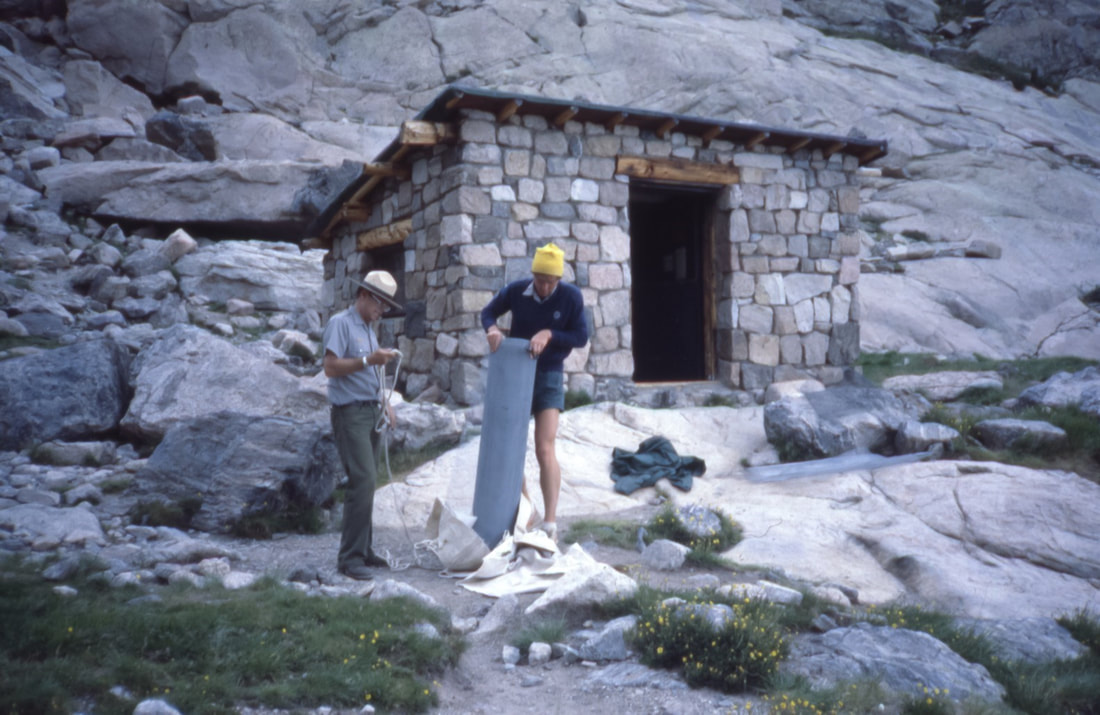

memoir and photos by Chris Reveley, Longs Peak Ranger 1979-1981  Bert McClaren and Chris Reveley unloading supplies in front of the (now-gone) Chasm Meadow cabin. The structure was used for many years as a cache for rescue gear; there were ropes, a litter and climbing hardware. There were also four bunks and old army surplus sleeping bags, in case rescuers had to spend the night. Climbing rocks, ice and big snowy mountains is dangerous. Sometimes people get hurt and occasionally they die. The job of search and rescue (SAR) first-responders is to deliver to the injured an appropriate level of care as efficiently and safely as possible without making matters worse. In the case of fatalities, body recovery is pursued whenever and wherever possible as long as the risks to SAR personnel are minimal. As in most of the U.S., SAR services in RMNP are available anytime, day or night, in all seasons. Those who do this work may be trained specialists employed by the Park, highly skilled individuals from the community who are called upon as-needed or qualified volunteers. They may reach the needy on foot, in vehicles, in boats or aircraft. In RMNP, SAR has taken place primarily on higher mountain terrain, though rescues and body recoveries in and around fast-moving water at lower elevations also occur. At times, cooperation with other SAR groups and the military has proved very valuable. For more than a century, Rocky has been fortunate to have a pool of highly skilled rock climbers and mountaineers close at hand, within the population of local instructors and guides. Recognized as valuable assets by Park managers, these individuals have frequently been called upon to assist with or sometimes direct SAR missions on highly technical terrain. Some of these experienced alpinists have found full-time employment and long-term careers with the NPS in Parks with traditionally high levels of technical climbing activity: Denali, Mt. Rainer, Yosemite, Teton and RMNP. This was the path that led me to the Longs Peak Ranger Station in 1978. Mountaineering hazards come in two primary flavors: objective and subjective. Objectively, mountains present variable surface conditions and atmospheric changes that when combined, can contribute to life- threatening situations. What's commonly called “bad luck” is often a feature of the predictably unpredictable and unstable mountain environment. Subjectively, climbers bring to the mountains various levels of experience, skill and judgement. With consideration of all possible variables and realistic assessment of a party's strengths, weaknesses and goals, climbing trips tend to turn out well. Poor planning, bad decisions and inadequate preparation are common contributors to bad outcomes. In the spirit of boldly going where others have not, mountaineers sometimes press on in the face of adversity and exhaustion to accomplish great feats. Our heroic dreams are egged-on by the human (often, male) endocrine system to lead us down harrowing, narrowing dark holes from which adrenaline and testosterone will not rescue the foolish. Just as aircraft disasters can sometimes be traced to a series of mis- judgements and bad decisions, analyses of mountaineering disasters often reveal a trail of errors from which we can all learn valuable lessons. Successful rescues of the injured are sometimes the product of one person's quick, decisive action. More often, they result from the work of a well-coordinated team with wise, experienced leadership and skilled, hard-working foot soldiers. One early summer morning in the late 1970s, I was visiting with campers at the Boulderfield site on Longs Peak when I received a radio call: a Park visitor hiking in the Chasm Lake Cirque had reported calls for help from “somewhere on the East Face”. I went over the ridge between Mount Lady Washington and Longs Peak, past the Camel formation, and descended into the Cirque. Shouting was actually coming from the Broadway ledge at the base of the Diamond on Longs Peak, one of the largest high-altitude walls in the U.S. and a popular destination for experienced rock climbers. I climbed the North Chimney on the Lower East Face and reached Broadway about 30 minutes after receiving the radio call. A climber had fallen from the poorly- protected, horizontally-traversing section of the so- called “casual route,” sustaining blunt trauma to various body parts in the long, pendulum-like fall. He was alert, moving all limbs and seemed fully oriented to the situation. Most worrisome, however, was his report of intense back pain between his shoulders. A quick exam revealed a very red, very swollen, tender-to-touch area over his mid-thoracic vertebrae. Back in radio-contact with the dispatch office, I asked them to mobilize the Park rescue team. Gathering rescue team members and necessary equipment was accomplished quickly at Park headquarters. The first members of the rescue group began to appear at the east end of Chasm Lake a few hours later. Leaving the injured climber warm, fed and watered in the company of his partner, I climbed back down the North Chimney and joined the team to help establish a line of fixed ropes up to Broadway. This allowed the dozen or so members of the team to ascend safely, carrying packs filled with ropes, climbing anchors and the two-piece, metal litter in which the injured climber would be lowered several hundred feet down the steep lower East Face. They also carried bivouac gear in case we had to spend the night. The day went by quickly. We established a safety zone for all the rescuers and built a multi- component, equalized anchor for the litter evacuation. The climber was placed in the litter and positioned without pressure on the injury. One of the Park's most experienced paramedics, Frank Fiala, secured himself to the litter's frame at the climber's head. I took up a position at the feet. Shoulder-mounted radios allowed us to communicate with those managing our descent. Mostly, we requested slack in either the head or foot line in order to keep the litter in a slightly head-up/foot- down orientation. The lowering took more than an hour. On the way down I remember feeling pretty good about the whole situation: On the litter, all three of our lives depended on expert management above. Charlie Logan, an experienced, long-time Ranger was in charge on Broadway; very comforting. The weather was holding, the injured climber was comfortable and not reporting worsening symptoms and we learned that Bob Greeno, a legendary helicopter pilot would be flying in for the rescue. Rumor had it that Bob had taken part in the “Helicopter Olympics” in Russia. None of us knew exactly what that meant but it sounded impressive. In 1967, he had rescued five survivors of an airplane crash, high on the slopes of Mount Sherman in Colorado. The feat was described by FAA officials as “…the most daring and spectacular mountain-top 'save' in aviation history.” Several of us had worked with Greeno and we valued his great skill and excellent judgement. Winds in the Chasm Cirque were constantly variable and tricky. The helicopter's only possible landing zone (LZ) was a large, flat boulder just below the snowfield under the lower East Face. A collective expression of joy and relief went up from the assembled rescue team when we heard that Bob was on his way. But darkness was approaching and we started to worry. It felt like time was of the essence with the climber's serious injury. We feared that bleeding or the swelling of soft tissue around the damaged vertebrae might impinge on his spinal cord and lead to permanent damage. At first, the little Alouette Lama helicopter sounded like a bumble bee as it turned west and started up the valley far below Chasm Lake. Within minutes, Greeno was hovering above us, surveying the LZ. The “large, flat boulder” suddenly looked smaller and a little tilted. If he couldn't execute the landing safely, he would have to leave, no negotiating. The helicopter danced directly above us as Bob tested the winds and viewed the LZ from several different angles. We were all hidden beneath the boulder's edge, well protected (in case things went very bad) but ready to approach the aircraft once he landed and gave us the thumbs up. Then, rather suddenly, down he came, placing both of the helicopter's skids perfectly on the exact center of the boulder. I peeked up over the edge. He nodded slowly and waved us in. The whole loading operation took about one minute. The litter with its precious cargo barely fit in the small aircraft. We stepped away, toward the helicopter's nose where Bob could see us and then…he was gone. Twenty minutes later Bob delivered the injured climber to a Denver hospital. Back in the Chasm Cirque there were cheers, tears and hugs. It had been a long exhausting day, physically and emotionally, and we all fell asleep easily amidst the rocks. Somewhat rested, we hiked out the next morning at first light. It was the next summer that the injured climber returned to the Longs Peak Ranger Station to thank us. He was fully recovered. Out of respect for the families of those who did not survive accidents, I won't speak about specific incidents here. I can write about the effects those searches and body recoveries had on me. Like many baby boomers raised in the middle-class suburbs of American cities, I had little first-hand experience with death. When we signed up for SAR work around Longs Peak, no one talked about the high probability that we would be searching for and retrieving severely damaged human bodies as a routine part of the job. I approached every response to a likely fatality with a degree of hesitation and an uncomfortable mixture of purpose, fear and anger. Indeed, this was part of a job I had accepted and I was duty-bound to proceed. I was reminded and frightened by how easily a moment of inattention or the choosing of a wrong path could lead to the end of a life in this environment where I moved so easily, perhaps a little too comfortable with the ever-present hazards. I was angered by those instances where the death was a result of negligence, ignorance and poor judgement on the part of the individual or those who were relied upon as leaders. And, I was stunned, thinking about the lifelong psychological and emotional pain the families would endure. I remember details of every one of those body recoveries and as I've passed by some of those locations in the last 40 years, I paused each time for a moment of sad reverence. For me, the deaths of children were always the most difficult to confront and process while going about our work.  Chris Reveley has spent 50 years climbing and doing endurance sports; and, thirty years learning and practicing medicine. “Now I’m a Happy House Husband with hobbies,” he said. The publication of this article from the April/May 2023 issue of HIKE ROCKY magazine was made possible by Inkwell and Brew and MacDonald Book Shop

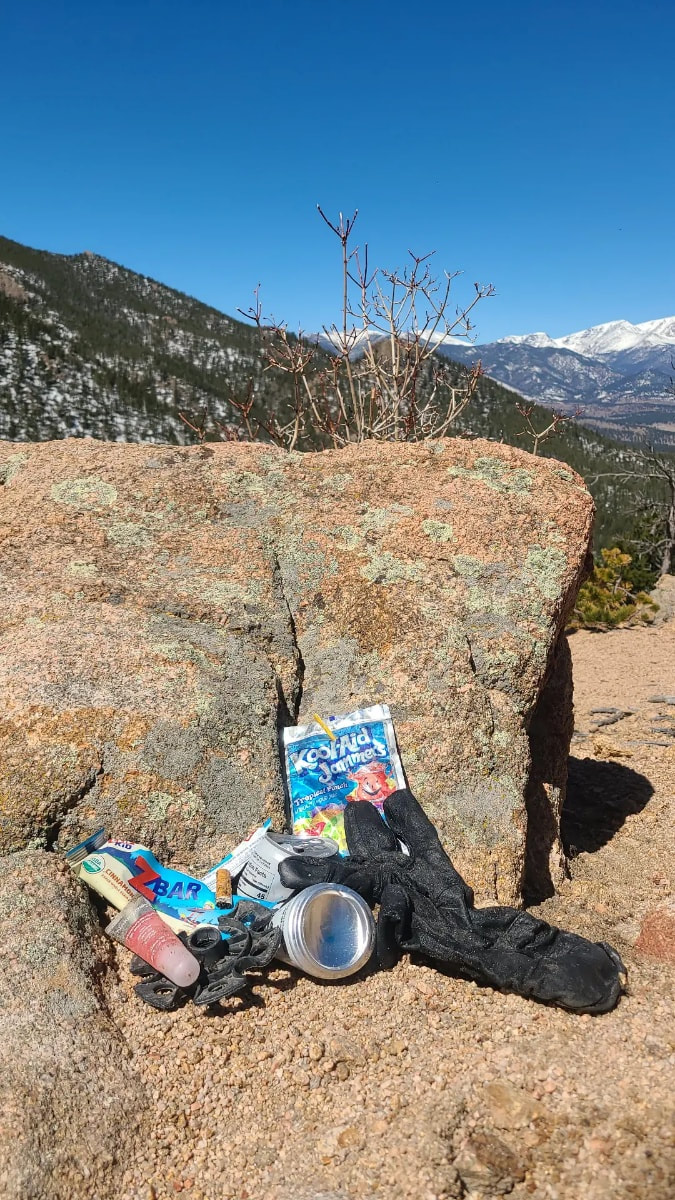

The Mad Moose and Xplorer Maps This story was pulled from the most recent issue of HIKE ROCKY magazine, which published April 30, 2023. For more information click here photos and story by Bronte Brooke As we move out of April, the coming of spring is evident. The change of the season brings life back into the mountains. In town, elk can be seen out and about. Fresh green grass pokes its way through the snow. Birds welcome the morning with song. The mother osprey at Lake Estes teaches her young to fly. People scatter the trails with friends and family. The snow melts and the weather warms, drawing eager admirers into the Rocky Mountains. But the reality of this influx of travelers has a flip side as well. As electric and alive as the wilderness feels with the surge of onlookers, it also leaves more room for mistakes. Last week while enjoying a sunset walk along Lake Estes, I noticed quite a bit of trash washing onto the shore. What started out as a leisurely stroll quickly transformed into an intentional trash cleanup after observing just how much scattered the trail. Then it occurred to me: more people outside means an increased risk for trash to be left behind. Whether it be families on picnics, anglers passing the time or hikers enjoying a snack after a long hike, there is an increased potential for things to be left behind in the outdoors. It's unfortunate, but it happens. I think we're all guilty of it. We stuff a granola bar wrapper into our pocket planning to throw it out later, but the wind grabs hold of it without us noticing. Or we get distracted photographing an elk and forget the cup of coffee we left sitting on the rock beside us. Mistakes happen even if we have the best intentions to clean up after ourselves. I'm hoping this serves as a reminder to make that extra effort to pack it in, pack it out. And if you notice a stray wrapper or broken piece of shoelace, take that extra moment to pick it up. We share this land with numerous different animals. The Rockies contain large herds of elk, a variety of birds, squirrels, chipmunks, deer and many other creatures. It's our responsibility to help protect this beautiful place they all call home. After what I saw on my walk around Lake Estes, I decided it was time to implement a change. In order to help maintain this Colorado oasis I've grown so fond of I've started integrating a new routine into my weekly schedule: trash cleanup walks. You can easily do this while already out hiking or plan a separate trip for it. Some things to consider bringing:

A quaint path circles the lake for a quick scenic stroll, but if you're looking for something slightly more challenging, Lily Ridge includes some more steep and rocky terrain. There are also a handful of other trails that can be accessed from the same trailhead, such as the Estes Cone for those seeking a real calf burner. But since the purpose of my hike was to cleanup trash in the park, I stuck with the more populated trails – Lily Lake and Lily Ridge. As I walked along, trash bag in hand, several people noticed my efforts and thanked me. It made my walk much more enjoyable, knowing I was doing something good for the planet and helping to maintain one of my favorite spots in Colorado. Trash items found on my walks: Lily Lake: Cigarette butts, granola bar wrappers, juice boxes, crushed cans, cough drop wrappers, chapstick, hair ties, used toilet paper, gum wrappers, chewed up gum, an old glove, disposable hand warmers, coffee cups and a children's shoe Lake Estes: A full tackle box, fishing line, chip bags, cigarette butts, Styrofoam, bait, pop bottles, pieces of plastic, candy wrappers, plastic water bottles and pieces of fabric amongst many other random scraps.  Trash items picked up around Lake Estes Trash items picked up around Lake Estes I think the hardest part about finding so much trash in the Park is knowing the negative affects it has on the local wildlife and our planet as a whole. I often see ducks at the lake with fishing line wrapped around their legs, wings or beaks. And as much as I'd love to help untangle it from their bodies, realistically it's nearly impossible to get close enough to do so. Birds and squirrels mistake trash such as gum or cigarette butts as food and get sick. Plastic items take decades to decompose, and frankly it draws away from the beauty of this amazing landscape. I was honestly shocked at some of the items I found, which is why I recommend bringing gloves or hand sanitizer on your cleanup walks; you never know what you'll stumble across. The amount of used toilet paper that I found at Lily Lake was truly atrocious, especially taking into account the fact that there are pit toilets at the trailhead parking lot, as well as numerous trash cans that can be found along the trail. Another item that stood out to me was the tub of bait at Lake Estes. I was about to throw it out when I noticed it was quite heavy and still felt rather full. Upon opening it up, I realized there were several live worms still inside. Seeing as the tub clarified they were local worms I found a soft patch of dirt and released them. The full tackle box also caught my attention. It had lures, hooks, and spare fishing line inside, perfectly intact. I hesitated to throw this item out, all still perfectly fine and usable. Instead, I sat it on top of the trashcan for another angler to find and utilize. That felt like the better choice instead of tossing it into the landfill to waste away and take years to decompose. I point these items out as an example of the things you'll stumble across, but also as an encouragement to take the extra step in thinking about how you dispose of the trash you find on your walks. Are there objects that could be recycled or composted? These are some of the things to consider. Maybe bring two bags with you; one for trash and another for recyclable items. Whether you implement intentional trash walks into your routine like I did, pick up items found while hiking or become more conscientious about packing it in and packing it out I hope this serves as a reminder to care for this wonderful planet we share. Have fun while doing it. Get out there! Bronte Brooke is an outdoor enthusiast, nature lover and adventure seeker. She’s spent the past two years living nomadically and traveling the states in her self-converted campervan with her two cats, Piper and Sotba. She unexpectedly found myself in Colorado this summer and haven't left since. Bronte is originally from the Pacific Northwest so she naturally fell in love with Colorado's landscape and the sense of "home" it's brought her. “The people I've met and the community I've built are what makes this place special to me,” said Bronte. The following business partners sponsored the publicaiton of this original content from HIKE ROCKY magazine: New Roots Real Estate, the Bank of Estes Park and Brownfield's

story and photos by Murray Selleck They're a touch heavy. They're stout and strong and beefy. They have covered some tough terrain over more miles than I can count. They are my full-grain leather, Goretex, durable, rockered, ankle protecting, Vibram soled Scarpa Zanskar* hiking boots. When I hike I don't leave home without them! I've had these boots for years and they show little wear and tear despite the heavy use. Full-grain leather offers a very durable boot construction. Cuts and scrapes into the leather do little to affect the life of the boot. If I relied on lightweight trail shoes these past years, I probably would have bought and replaced at least five or six pairs instead of relying on my single pair of leather boots. The math and money quickly reveal you get what you pay for. The weight of a full-grain leather boot, of course, will be more than a trail running shoe or lightweight hiker. Perhaps it is my mindset or that the benefits of this kind of boot are so ingrained into my thinking I don't notice the weight. I haven't felt any more tired at the end of the day than any of my hiking partners due to the weight of my footwear. I do know that often some of my hiking buddies wearing softer footwear are bit slower when the pace when we're navigating a steep boulder field or traversing a slippery angled slope of scree. “Fast and Light” is the mantra of many a hiker, however, the rest of that story might include “fast to wear out and fast to replace.” I believe there is much to say about sustainability and durability and that includes my choice in footwear. My leather boots are strong torsionally and the sole protects my feet from sharp stones and sharp edged boulders. I can pretty much step anywhere with confidence. I don't feel the boot sole folding over rocks and I can edge into a loose traverse keeping my footing. The boot sole creates a strong platform that supports my foot. The benefit is my feet don't get beat up during big mileage days. An additional benefit to footwear with good torsional sole strength is protecting your ankles from a nasty twist or sprain. Soft trail running shoes or lightweight hikers that can be twisted like a wet sponge offer little in protecting you from a sprained ankle. I like a long, injury-free hiking season! The fact that my boots are waterproof speaks to their multi-seasonal functionality. Early spring hikes when snowdrifts as big as whales attempt to block the trail, I find it easy to stay on route. I can easily kick into drifts and snowfields creating a secure staircase of steps. When summer monsoons dump not only rain, but also hail and grapple turning dusty trails into liquid channels of water and mush, my feet stay dry. And in the fall, when an early snow tries to cut the hiking season short, a Goretex waterproof boot (or equivalent) extends the hiking season until we happily replace our hiking boots with skis and snowshoes! Lightweight, breathable, non-waterproof shoes in any of these situations will have your socks soaked and feet cold and miserable. Long ago I learned hiking when your feet feel like cold stumps and you can no longer feel the trail beneath frozen feet is no way to happily cover distance. In fact, you just can't get home quick enough. The Vibram soles on my boots have plenty of tread life left and the secure traction the boot sole provides is a wonderful thing. As mentioned above, when your boots have a nice lugged sole with bombproof traction stepping up and on to teeter-tottering boulders is easy. Keeping your footing while on snowfields or tromping along slushy trails is just what you do. No hesitation, no route finding dilemma, just do it! Most leather boots have a rockered sole. That is the sole is pretty flat along the length of your boot but up toward the toes the sole bends upward. This is called rocker. Rocker helps propel you forward. There is a designed mechanical benefit built into the boot sole to roll your stride forward comfortably even in a beefy leather boot. Rocker offers a very natural walking feel to the boots. My Scarpa boots are cut above my ankle bones. Those of you who like to hike in trail running shoes are cringing. However, it has been a very long time since the outside of my ankles have clipped a trailside rock sending me cringing, cursing and hopping up and down the trail with tears in my eyes. Above-the-ankle cut boots offer more ankle bone protection. And when the time comes, my boots will be able to be resoled. New rubber. New tread. New life! Rocky Mountain Resole in Salida, Colorado does a terrific job at extending the life of many kinds of boots. As long as I keep the uppers in reasonable shape, a new Vibram sole can be applied. One small step for man, one giant leap for keeping your favorite boots! I believe most hikers have forgotten how versatile a leather boot can be. The trend in footwear for hiking over the past decade has been to use trail running shoes. I won't argue that point. What I will argue for is that if you are not convinced a leather hiking boot is in your future at the very least make sure your trail running shoes or light hikers are waterproof. Leave No Trace Ethics teach us to stay on the trail. If there is a muddy bog or puddle we should walk right through it splishing and splashing. Leave No trace teaches you to prepare for your hike or backpack trip before you leave. A big part of preparation is proper footwear. Walking around mud puddles only widens the trail. Or worse yet, multiple parallel trails are created as hikers detour farther afield just to keep their shoes from getting wet. Trampling fragile vegetation and creating unintended trails is not good. Think. Plan. Prepare. And hike as if you are the first but not the last! *The Scarpa Zanskar is no longer in production. However, the Scarpa Kinesis Pro GTX, Kailash Plus GTX, and Terra GTX are all great leather boot choices.  Murray Selleck moved to Colorado in 1978. In the early 80s he split his time working winters in a ski shop in Steamboat Springs and his summers guiding on the Arkansas River. His career in the specialty outdoor industry continued for more than 30 years. Needless to say, he has witnessed decades of change in outdoor equipment and clothing. Steamboat Springs continues to be his home. This piece of original content was sponsored by our Estes Park business partners including Affinity Massage & Wellness Center, The Country Market and Images of RMNP