|

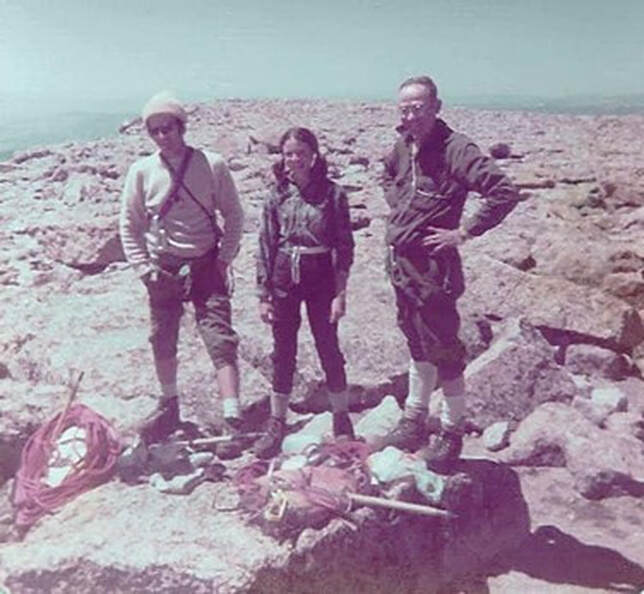

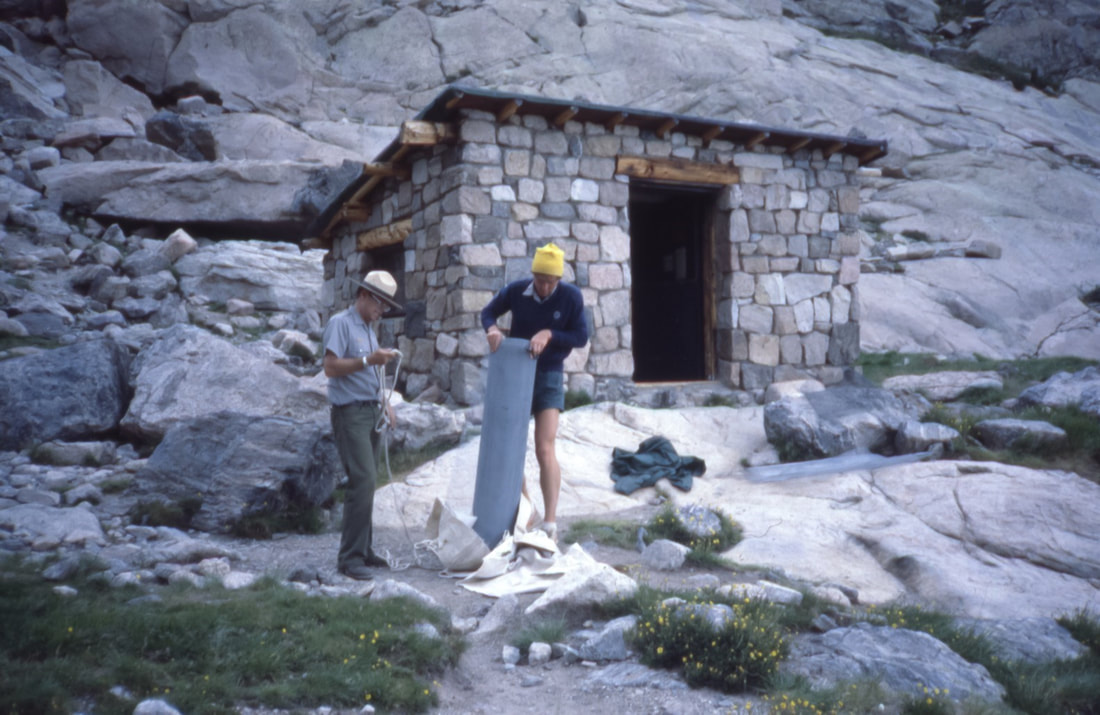

memoir and photos by Chris Reveley, Longs Peak Ranger 1979-1981  Bert McClaren and Chris Reveley unloading supplies in front of the (now-gone) Chasm Meadow cabin. The structure was used for many years as a cache for rescue gear; there were ropes, a litter and climbing hardware. There were also four bunks and old army surplus sleeping bags, in case rescuers had to spend the night. Climbing rocks, ice and big snowy mountains is dangerous. Sometimes people get hurt and occasionally they die. The job of search and rescue (SAR) first-responders is to deliver to the injured an appropriate level of care as efficiently and safely as possible without making matters worse. In the case of fatalities, body recovery is pursued whenever and wherever possible as long as the risks to SAR personnel are minimal. As in most of the U.S., SAR services in RMNP are available anytime, day or night, in all seasons. Those who do this work may be trained specialists employed by the Park, highly skilled individuals from the community who are called upon as-needed or qualified volunteers. They may reach the needy on foot, in vehicles, in boats or aircraft. In RMNP, SAR has taken place primarily on higher mountain terrain, though rescues and body recoveries in and around fast-moving water at lower elevations also occur. At times, cooperation with other SAR groups and the military has proved very valuable. For more than a century, Rocky has been fortunate to have a pool of highly skilled rock climbers and mountaineers close at hand, within the population of local instructors and guides. Recognized as valuable assets by Park managers, these individuals have frequently been called upon to assist with or sometimes direct SAR missions on highly technical terrain. Some of these experienced alpinists have found full-time employment and long-term careers with the NPS in Parks with traditionally high levels of technical climbing activity: Denali, Mt. Rainer, Yosemite, Teton and RMNP. This was the path that led me to the Longs Peak Ranger Station in 1978. Mountaineering hazards come in two primary flavors: objective and subjective. Objectively, mountains present variable surface conditions and atmospheric changes that when combined, can contribute to life- threatening situations. What's commonly called “bad luck” is often a feature of the predictably unpredictable and unstable mountain environment. Subjectively, climbers bring to the mountains various levels of experience, skill and judgement. With consideration of all possible variables and realistic assessment of a party's strengths, weaknesses and goals, climbing trips tend to turn out well. Poor planning, bad decisions and inadequate preparation are common contributors to bad outcomes. In the spirit of boldly going where others have not, mountaineers sometimes press on in the face of adversity and exhaustion to accomplish great feats. Our heroic dreams are egged-on by the human (often, male) endocrine system to lead us down harrowing, narrowing dark holes from which adrenaline and testosterone will not rescue the foolish. Just as aircraft disasters can sometimes be traced to a series of mis- judgements and bad decisions, analyses of mountaineering disasters often reveal a trail of errors from which we can all learn valuable lessons. Successful rescues of the injured are sometimes the product of one person's quick, decisive action. More often, they result from the work of a well-coordinated team with wise, experienced leadership and skilled, hard-working foot soldiers. One early summer morning in the late 1970s, I was visiting with campers at the Boulderfield site on Longs Peak when I received a radio call: a Park visitor hiking in the Chasm Lake Cirque had reported calls for help from “somewhere on the East Face”. I went over the ridge between Mount Lady Washington and Longs Peak, past the Camel formation, and descended into the Cirque. Shouting was actually coming from the Broadway ledge at the base of the Diamond on Longs Peak, one of the largest high-altitude walls in the U.S. and a popular destination for experienced rock climbers. I climbed the North Chimney on the Lower East Face and reached Broadway about 30 minutes after receiving the radio call. A climber had fallen from the poorly- protected, horizontally-traversing section of the so- called “casual route,” sustaining blunt trauma to various body parts in the long, pendulum-like fall. He was alert, moving all limbs and seemed fully oriented to the situation. Most worrisome, however, was his report of intense back pain between his shoulders. A quick exam revealed a very red, very swollen, tender-to-touch area over his mid-thoracic vertebrae. Back in radio-contact with the dispatch office, I asked them to mobilize the Park rescue team. Gathering rescue team members and necessary equipment was accomplished quickly at Park headquarters. The first members of the rescue group began to appear at the east end of Chasm Lake a few hours later. Leaving the injured climber warm, fed and watered in the company of his partner, I climbed back down the North Chimney and joined the team to help establish a line of fixed ropes up to Broadway. This allowed the dozen or so members of the team to ascend safely, carrying packs filled with ropes, climbing anchors and the two-piece, metal litter in which the injured climber would be lowered several hundred feet down the steep lower East Face. They also carried bivouac gear in case we had to spend the night. The day went by quickly. We established a safety zone for all the rescuers and built a multi- component, equalized anchor for the litter evacuation. The climber was placed in the litter and positioned without pressure on the injury. One of the Park's most experienced paramedics, Frank Fiala, secured himself to the litter's frame at the climber's head. I took up a position at the feet. Shoulder-mounted radios allowed us to communicate with those managing our descent. Mostly, we requested slack in either the head or foot line in order to keep the litter in a slightly head-up/foot- down orientation. The lowering took more than an hour. On the way down I remember feeling pretty good about the whole situation: On the litter, all three of our lives depended on expert management above. Charlie Logan, an experienced, long-time Ranger was in charge on Broadway; very comforting. The weather was holding, the injured climber was comfortable and not reporting worsening symptoms and we learned that Bob Greeno, a legendary helicopter pilot would be flying in for the rescue. Rumor had it that Bob had taken part in the “Helicopter Olympics” in Russia. None of us knew exactly what that meant but it sounded impressive. In 1967, he had rescued five survivors of an airplane crash, high on the slopes of Mount Sherman in Colorado. The feat was described by FAA officials as “…the most daring and spectacular mountain-top 'save' in aviation history.” Several of us had worked with Greeno and we valued his great skill and excellent judgement. Winds in the Chasm Cirque were constantly variable and tricky. The helicopter's only possible landing zone (LZ) was a large, flat boulder just below the snowfield under the lower East Face. A collective expression of joy and relief went up from the assembled rescue team when we heard that Bob was on his way. But darkness was approaching and we started to worry. It felt like time was of the essence with the climber's serious injury. We feared that bleeding or the swelling of soft tissue around the damaged vertebrae might impinge on his spinal cord and lead to permanent damage. At first, the little Alouette Lama helicopter sounded like a bumble bee as it turned west and started up the valley far below Chasm Lake. Within minutes, Greeno was hovering above us, surveying the LZ. The “large, flat boulder” suddenly looked smaller and a little tilted. If he couldn't execute the landing safely, he would have to leave, no negotiating. The helicopter danced directly above us as Bob tested the winds and viewed the LZ from several different angles. We were all hidden beneath the boulder's edge, well protected (in case things went very bad) but ready to approach the aircraft once he landed and gave us the thumbs up. Then, rather suddenly, down he came, placing both of the helicopter's skids perfectly on the exact center of the boulder. I peeked up over the edge. He nodded slowly and waved us in. The whole loading operation took about one minute. The litter with its precious cargo barely fit in the small aircraft. We stepped away, toward the helicopter's nose where Bob could see us and then…he was gone. Twenty minutes later Bob delivered the injured climber to a Denver hospital. Back in the Chasm Cirque there were cheers, tears and hugs. It had been a long exhausting day, physically and emotionally, and we all fell asleep easily amidst the rocks. Somewhat rested, we hiked out the next morning at first light. It was the next summer that the injured climber returned to the Longs Peak Ranger Station to thank us. He was fully recovered. Out of respect for the families of those who did not survive accidents, I won't speak about specific incidents here. I can write about the effects those searches and body recoveries had on me. Like many baby boomers raised in the middle-class suburbs of American cities, I had little first-hand experience with death. When we signed up for SAR work around Longs Peak, no one talked about the high probability that we would be searching for and retrieving severely damaged human bodies as a routine part of the job. I approached every response to a likely fatality with a degree of hesitation and an uncomfortable mixture of purpose, fear and anger. Indeed, this was part of a job I had accepted and I was duty-bound to proceed. I was reminded and frightened by how easily a moment of inattention or the choosing of a wrong path could lead to the end of a life in this environment where I moved so easily, perhaps a little too comfortable with the ever-present hazards. I was angered by those instances where the death was a result of negligence, ignorance and poor judgement on the part of the individual or those who were relied upon as leaders. And, I was stunned, thinking about the lifelong psychological and emotional pain the families would endure. I remember details of every one of those body recoveries and as I've passed by some of those locations in the last 40 years, I paused each time for a moment of sad reverence. For me, the deaths of children were always the most difficult to confront and process while going about our work.  Chris Reveley has spent 50 years climbing and doing endurance sports; and, thirty years learning and practicing medicine. “Now I’m a Happy House Husband with hobbies,” he said. The publication of this article from the April/May 2023 issue of HIKE ROCKY magazine was made possible by Inkwell and Brew and MacDonald Book Shop

The Mad Moose and Xplorer Maps

6 Comments

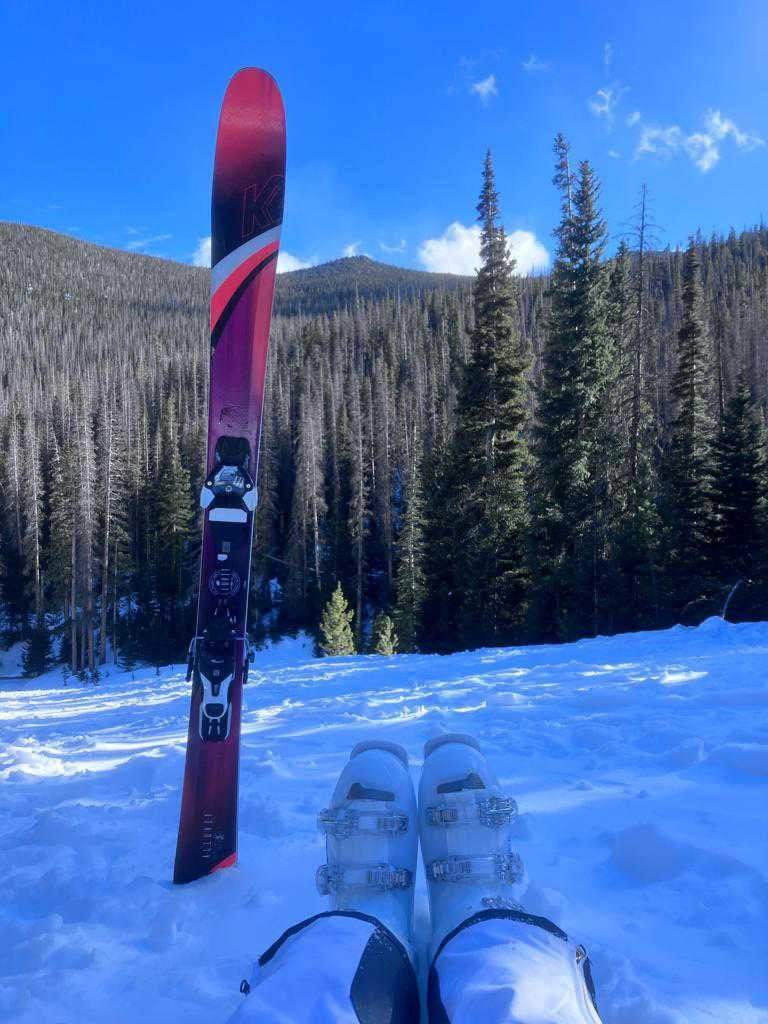

story by Bronte Brooke video footage and photos by Barb Boyer Buck I stumbled across Estes Park this summer and completely fell in love with the area, so it was a surreal feeling getting to experience Rocky Mountain National Park in winter. It had a completely different feel from the hikes I did there back in August. As someone who embraces the cold, I'd been eager to get back there for a winter hike. However, I kept coming up with excuses: not owning a pair of snowshoes, unsure of how to approach hiking in the snow, etc. I'd been pushing it off. Then a friend told me about Hidden Valley: an abandoned ski resort nestled in the heart of Rocky. Of course, as an avid skier, my interest was piqued. My partner and I invited a couple of friends, Hammy and Chucky, to join us and we made a day of it. We work at a ski resort together, so spending all day in the mountains isn't foreign to us; it's become our backyard at this point. But Hidden Valley was a whole new adventure, different than anything we'd done before. The area is a beautiful fusion of hiking and skiing, where backcountry meets established runs. It has the perks and feel of a ski resort without the hassle and millions of people. There are long established runs left untouched, waiting for anyone willing to make the extra trek. You can see sections where lifts used to be and your imagination wanders, filling in the empty spaces, envisioning what it used to look like back in the day. There was a magical feeling, knowing I was standing there experiencing a part of local history. I've been skiing for nearly three seasons now, and finally reaching the point where a typical downhill blue feels a bit like a leisurely drive down the highway. I've been itching for a little more excitement and a few less people, but the idea of fully diving into backcountry skiing intimidated me. The added gear and dangers were also a deterrent. That's why Hidden Valley was such an incredible experience for me! There is that added challenge and satisfaction of having to hike up, rather than simply hopping onto a chairlift. Not having to spend half the day waiting in line? Sign me up! We basically had the place to ourselves, with the exception of a few cross country skiers and snowshoers. Everywhere I looked I was surrounded by beauty, secluded in this hidden oasis. My initial fears of getting lost in tight trees soon dissipated. The area is established enough to feel safe and comfortable, yet removed and remote enough to feel the peace and quiet of the wilderness. The hiking aspect brought me back to that nostalgic feeling of being a kid again; trekking up the tallest hill in the neighborhood just to sled down and then do it all over again. As a crew, we took turns picking out hills that looked fun to shred down and worthwhile to haul our gear up. Some had jumps, some had mellow gradients that wound and wove through scenic terrain. But the best part was that we had no idea what to expect until we reached the top. It was the excitement of the unknown: pick a direction, pick a hill, hike up and send it down! A true “choose your own adventure.” On one of the runs, we hiked quite a way up and took a moment to soak in the views before taking turns riding down. It was so peaceful - a completely different tone than skiing at a resort with all the hustle and bustle. There is a childlike innocence to it all, a feeling of freedom. It felt casual and carefree. We took turns filming each other hitting jumps, hyping one another up. It felt like that first snow day of the season back in middle school: classes cancelled, spending hours sledding ‘til my legs felt like Jell-o and my stomach sloshed full of all the hot chocolate I’d consumed throughout the day. It was a feeling I hadn't felt in quite some time. To top the day off, we had a tailgate cookout in the parking lot before parting ways for the night. As the sun began to set, dainty snowflakes trickled down from the sky, speckling everything in sight with a light powdered sugar dusting. Families drove in to let their kids sled down the bunny slopes before heading home for dinner. We set up our propane stove and sautéed veggies that Hammy had cut up the night before. It was a true campout stir fry of sorts. It brought me back to memories of the summer, backpacking with friends along the Big Thompson River and waking up to make breakfast amongst the birds. If there's one word to summarize my experience at Hidden Valley it's “Nostalgia.” Memories of summer hikes in the Rockies, flashbacks to sledding adventures with friends as a kid, and an overall carefree feeling that reminded me why I have so much love for snowy winters in the Rockies. Don't get me wrong, I absolutely love the summertime in Rocky, but there's something magical about playing around in the snow.

This original content was made possible by: Ram's Horn Village Resort and Tahosa Coffee House

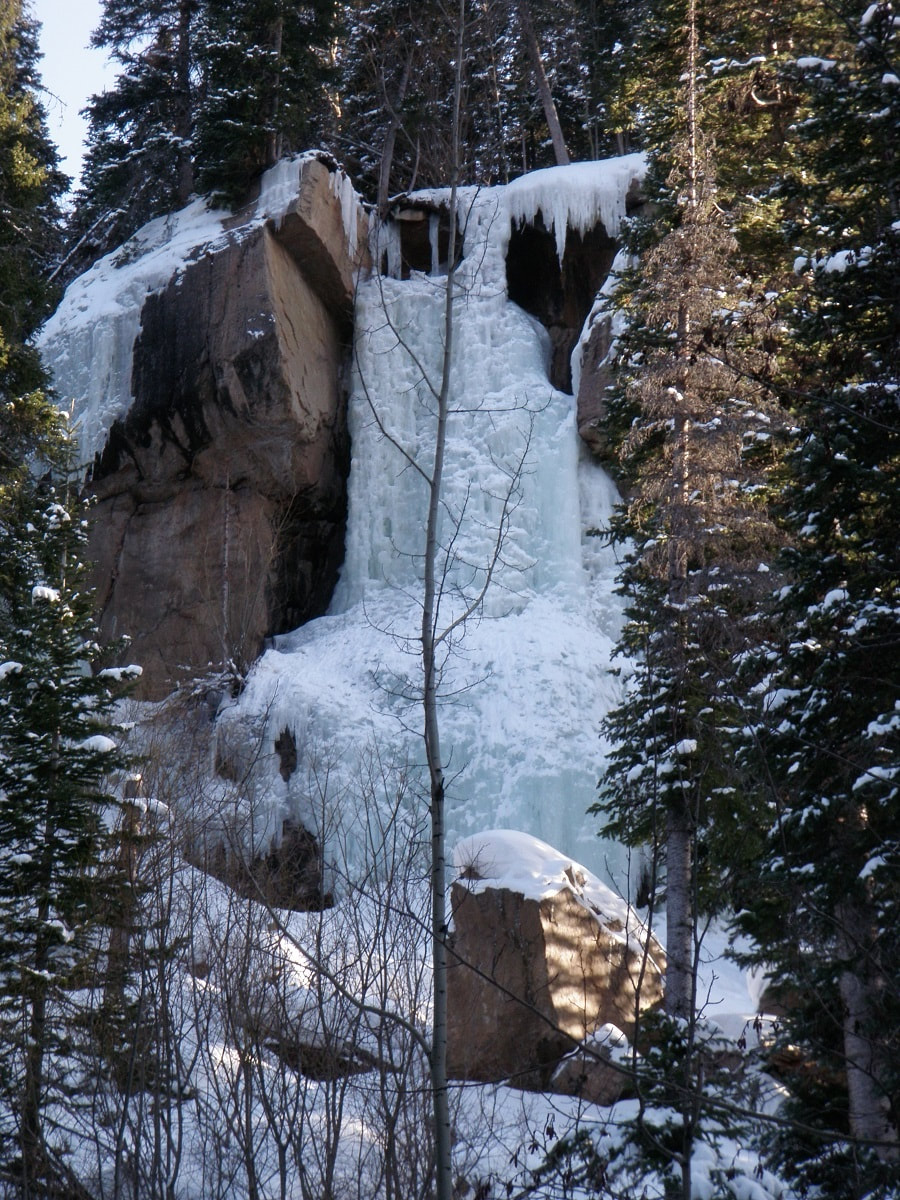

story and photos by Rebecca Detterline The golden peach light hitting the December snow on these shortest days of the year always brings me to a place of quiet contemplation. Pausing at the Saint Vain bridge 2.4 miles from the Wild Basin winter parking area, I breathe in the cold winter air and reflect on the past decade. When I moved to Allenspark in 2012, Wild Basin quickly became my sanctuary. Whether fly fishing in Ouzel Creek, tagging a remote summit or jogging up the Finch Lake trail, I always feel at home in The Basin. During the winter season, the far reaches of Wild Basin are inaccessible to most of us mortals, buried deep under an untouched blanket of snow. Skiing off the summit of Mount Copeland in January of 2017 required starting in the pre-dawn darkness and ‘over-skiing my headlamp’ on a dark, icy trail well after sunset. I almost made it to Thunder Lake on skis in early 2020, but breaking trail in deep snow, route-finding difficulties, and the impending sunset forced my partner and I to turn around just 1/2 mile shy of the lake. The Wild Basin winter parking area will sometimes fill up on busy winter weekends, but spots can usually be found in the nearby summer stock parking loop. Weekdays, however, offer much solitude. Hikers can plan to share the one-mile stretch of road between the parking area and the Wild Basin trailhead with a handful of ice climbers, cross-country skiers, and families trying out rental snowshoes. The road is usually hard packed, as is the short trail that leads to Hidden Falls. However, hikers should carry snowshoes and anticipate breaking trail for destinations along the Wild Basin Trail. In the summer months, Hidden Falls is nothing more than a trickle of water seeping out of an overhanging rock ,100 feet above the forest floor. In the winter, that trickle transforms into a spectacular frozen waterfall, very popular among ice climbers. The round trip distance for this hike is approximately 3.5 miles. From the parking area, follow the road past the Finch Lake trailhead. Just before the road takes a sharp right and crosses the North Saint Vrain Creek, look for a sign for a horse trail and follow the hard-packed trail to Copeland Falls. Continue along the trail, looking to the south for glimpses of this impressive ice column. The climbers’ trail heads up to the left and is generally easy to spot. This trail steepens and continues to the base of the falls, but quickly becomes covered in solid ice. Crampons are needed for this section of trail and hikers should enjoy the views of Hidden Falls from below this icy slope, safely out of the way of any falling ice chunks the climbers might dislodge. Ouzel Falls is a worthy destination in any month of the year, but the most solitude is found on the shortest days. But hikers need not travel 3.7 miles from the winter parking area to enjoy the quietude of Wild Basin in the wintertime. Only .3 miles from the Wild Basin trailhead, winter hikers can revel in the rare opportunity to have Copeland Falls all to themselves. Pausing at the bridge that crosses the North Saint Vrain Creek 2.4 miles into the hike, I watch the water flow between the rock slabs and ice sheets that encase them. So much literal and proverbial water has flowed under this bridge in the years since I’ve made this place my refuge. Through triumphs and heartbreaks, fires and floods, anguish and joy, the trails in Wild Basin have been an enduring comfort. The seasons of life are not so predictable as the seasons of the year, but the ever- flowing snowmelt in the creeks and waterfalls of this magical place always brings a sense of peace. Whether hiking to Hidden Falls, Copeland Falls, Calypso Cascades, Ouzel Falls or destinations beyond, the tranquil solitude of a winter visit to Wild Basin is sure to leave the hiker feeling refreshed and rejuvenated. The darkest days are behind us now and Wild Basin is an ideal spot for quiet reflection as we begin heading for light.  Rebecca Detterline is a lover all things RMNP. She is a wildflower aficionado whose favorite hiking destinations are alpine lakes and waterfalls. Her name can be found in remote summit registers in Wild Basin and beyond. Originally from Minnesota, she has lived in Allenspark since 2011. The publication of this piece was made possible by the Mad Moose, and the Country Market, both of Estes Park.

Memoir and photos by Chris Revely Author's NoteMy next few contributions to HIKE ROCKY are based on recollections of four years of employment with the National Park Service (1978 – '81), served mostly around Longs Peak. These memories are vivid. But are they completely true? In the late 1970s, rumors of high winds around Estes Park had reached the East Coast. Meteorologists working on Mount Washington in New Hampshire, where a long-standing world-record wind speed of 234 mph was measured, wondered if that record might be broken along the Continental Divide in Rocky Mountain National Park. As a Longs Peak backcountry ranger, I was recruited to assist with the construction of a wind measuring device on the summit of Longs Peak. Later, the project would require more extensive, personal involvement. In the Fall of 1980 (or was it '81? See authors note) personnel and equipment were assembled at an often-used staging area along the upper Beaver Meadows road. The helicopter arrived and over two days, we made several flights loaded with tools and materials to the summit of Longs Peak . Having proudly struggled to the summit of Longs scores of times under my own power, the experience of rising, effortlessly, in one unbroken line of ascent from the take-off point to the top was both exhilarating and eerily disturbing. My thoughts toggled back and forth between, “WOW!!! What an amazing machine” and “There is just something wrong about getting to the top of Longs like this.” On the flat summit about 100 yards northwest of the often-visited high point, a solid metal mast with its spinning anemometer attached, was secured in a vertical position with several heavy-gauge steel wires tightly anchored to large rocks. Thin transmission wires wound down the post and reached the recording apparatus near the base. We were assured by the Mount Washington team that this arrangement could withstand anything the atmosphere might dish out. As a resident Park Ranger at the Longs Peak trailhead that year, I was unanimously elected (at a meeting I don't recall attending) to service the wind measuring apparatus throughout the winter. It was a project I naively and enthusiastically embraced due in part to the competitive verve that had sprung up around the project. Could Longs Peak beat Mount Washington? Data from the anemometer would be recorded by a stylus on paper if - and only if - the tension spring that turned the paper's cylinder was wound up regularly, like winding an old-fashion grandfather clock. The winding, I was told, should take place once weekly (?!!). The magnitude of the project and my responsibility became disturbingly clear: it would entail frequent trips to the mountain's summit from the Longs Peak trailhead, throughout the winter. Success would depend on regular, reasonable climbing conditions on twenty separate days, from November through March. (Hmmmm….. lots of unspoken ifs in that plan). The winding of the apparatus was achieved with a metal wrench. I would have to remove my heavy, outer mittens and execute the essential maneuver wearing little or nothing on my hands while being slapped around by icy gusts on the exposed plateau. I knew that conditions around the summit would sometimes be so extreme as to preclude reaching the contraption, much less performing the necessary activities out in the open. A plywood coffin-like structure was designed, built and snuggly fitted up against the recorder. Entry to the long narrow box was made through the opposite end, which was fitted with a hinged door. This seemed to solve the problems of access and protection. Once weekly, I left the trailhead with plenty of clothing, food and water. I carried two ice-climbing tools, crampons, a light rope and a few pieces of gear to a place of protection in case conditions on my preferred approach (the North Face) required self-belay. Once past the technical difficulties of the old Cables route, the remainder of the climb involved only kicking steps in snow and finding my way over and around large boulders to the edge of the summit plateau. From there, the last leg of the approach resembled trench warfare. At just the right moment, having waited for a break between volleys of wind, I would break into the open, fully exposed to fire from the enemy, and proceed, crab-like, zigzagging on hands and feet to the coffin, my only point of cover. Once inside, I could relax and take care of business. That winter, between November and late February, I reached the summit (of Longs) on fewer than half of my attempts. My journey to the top always started with the best intentions but often ended in a hail of flying gravel and battering wind below the Chasm View overlook. While the recorder waited patiently for its recharge, I wound it up, more often than not, laying on my side, curled on the floor of a body-size crack below the North Face, laughing at the absurdity of my pitiful situation. At those moments, the decision was easy; if I can't go on safely, it’s time to go down. Turn around at any point on that route and it is all downhill and down-wind to the trailhead. The irony of my situation was, however, harder to escape: There I lay, defeated by extreme wind, the very phenomenon we were most hoping to record. Throughout the winter, I the reached the site when I could and information continued to be collected. Sometime in late February, the steel mast came down and wires were scattered across the summit by (of course) high wind. On New Hampshire's Mount Washington, weather data is collected throughout the year from instruments mounted atop bunker-like, reinforced buildings. Weather station employees travel to the 6,288-foot summit in heated snowcats, spending several days in residence reading instrument gauges while sipping coffee in heated work areas. By comparison, our approach to the hunt for high wind on the 14,256-foot summit of Longs Peak was laughably inadequate; poorly conceived, badly executed and doomed to failure from the beginning. Longs Peak did not officially win the wind speed contest. But I'm not entirely sure it lost. We will never know exactly how much faster the wind blew after the equipment was flattened. Is it worth another try? Today, with improved technology, more sophisticated equipment and a better understanding of wind dynamics around surface features, the odds of success would certainly improve. I suspect there may still be world-record wind waiting to be found among the high peaks of Rocky Mountain National Park. Read a brief synopsis of the wind research project on Rocky Mountain National Park’s website; and, DE Glidden’s report on this project, which was funded by the Rocky Mountain Conservancy is also available online.  Chris Reveley has spent 50 years climbing and doing endurance sports; and, thirty years learning and practicing medicine. “Now I’m a Happy House Husband with hobbies,” he said. The publication of this story was made possible by Images of RMNP and Brownfields.

Story and photos by Rebecca Detterline, Estes Park “Auntie, my legs are feeling tired. Can you carry me?” Of course my niece, Adeline, is completely oblivious to the fact that I am already carrying a 45-pound backpack and both of my hands are occupied with the trekking poles I am using in an attempt to keep myself from tripping and falling, adding more scrapes and bruises to the bodily evidence of my backcountry clumsiness. At first, indulging this small request on short hikes seems harmless. Like a candy bar in the grocery store checkout line, it could quickly de-escalate a meltdown or even prevent one altogether. Additionally, unlike a trip to get groceries, a trip into the backcountry with children is totally optional and perhaps even self- serving for the adults organizing it. A child screaming to go home in the middle of a trail only half a mile from the trailhead doesn't exactly make me look like Auntie of the Year. I remind myself that she has done this to me on several summer backpacking trips and backcountry winter hut trips and that she always has an absolute blast once she arrives at the destination with her friends. She sobbed her eyes out while I shoveled M&Ms and gummy bears into her mouth on her first chair lift rides and now she loves them. She even had the audacity to look me straight in the eyes at water park and say, “Little girls never get to do anything fun." I am the adult here and I like to believe that my thought process is a bit more rational than that of a four-year- old. “No, buddy. My pack is too heavy and you are big girl now and you're going to have to walk to the campsite.” I feel sorry for interrupting the quiet solitude for the hikers passing by during her complete and utter emotional meltdown, and of course I feel a twinge of embarrassment as passersby look on with sympathy and what I imagine to be complete disapproval. In one minute, they will be several yards up the trail, enjoying their hike once more. I, on the other hand, hope to be hiking, camping and skiing with this child for the course of her outdoor upbringing and hopefully the rest of her life. So, my first piece of advice is: Let 'em scream. It's embarrassing and cringe-worthy and people might look down on you, but you are setting a precedent here and you need to stand your ground. My second tip strays a bit from the approach I just spent several paragraphs defending. Your job as the adult is to get this child to walk or run or gallop or cartwheel all the way to the campsite by whatever means necessary. Bribery with snacks has proven to be a highly effective strategy and the kids are burning through the calories like little hummingbirds anyway. For some kids, dried strawberries and organic crackers will motivate them for miles. Adeline requires sour gummy worms, chocolate and Teddy Grahams to maintain a pace of one half mile per hour. Speaking of pace, it is probably not going to be brisk. As an adult, I like to put my head down, hike quickly to camp, get my backpack off and start enjoying my time in the woods. Hiking with a child brings enjoying the journey rather than solely focusing on the destination to a whole new level. Every boulder, bog bridge and dilapidated cabin is an adventure waiting to happen. I've found the best strategy is to let the kids stop and really play a couple of times along the route. On a recent trip to the Moore Park campsite, we stopped at the Eugenia Mine for an hour on the way in and out. Once at camp, kids are pretty quick to entertain themselves. Sticks and rocks and imagination combined go a long way. I always bring a tarp and parachute cord to build a shelter in case of rain. A lightweight hammock is always a hit and books are great for winding down at bedtime. A string of battery-powered LED lights create a nice ambient light for kids who like to sleep with a night light. The one children's gear splurge that I absolutely swear by is the Big Agnes sleep system. The integrated sleeping pad sleeve keeps kiddos from sliding around and the bags are rated to 15 degrees. However, there is no need to spend a bunch of money to get your kids into the backcountry. Borrow a sleeping bag and sleeping pad from a friend or use of your old ones. Individual sites allow a maximum of seven people and group sites a maximum of twelve. Going with a group is always more fun. The kids can motivate each other by chasing one another down the trail and entertain each other while the adults set up camp, cook and collect water. Wilderness permits for backcountry camping become available on recreation.gov in early March and the most sought-after sites get booked within seconds. However, most child-friendly sites are not highly coveted, and I've had no trouble getting my first or second choice as long as I'm the website the day that reservations open. There were still a good amount of availability for many of these sites in September 2022. There are several sites in Rocky Mountain National Park within two miles of the trailhead. Specific information on all backcountry sites, including distances and elevation gain is available at https://www.nps.gov/romo/planyourvisit/site_details.htm. List of Recommended Campsites for Backpacking with Children: Cow Creek TH: Rabbit Ears, Peregrine Cub Lake TH: Cub Creek Hollowell Park TH: Mill Creek Basin, Upper Mill Creek Sprague Lake or East Portal TH: Wind River Bluff, Over the Hill, Upper Wind River Fern Lake TH: Arch Rock, Old Forest Inn Longs Peak TH: Moore Park, Goblin's Forest Wild Basin TH: Pine Ridge, Tahosa East Inlet TH: East Meadow North Inlet TH: Summerland Park Green Mountain TH: Big Meadows Group  Rebecca Detterline is a lover all things RMNP. She is a wildflower aficionado whose favorite hiking destinations are alpine lakes and waterfalls. Her name can be found in remote summit registers in Wild Basin and beyond. Originally from Minnesota, she has lived in Allenspark since 2011. The publication of this article was made possible by Rock Creek Tavern and Pizzeria of Allenspark and MacGregor Mountain Lodge of Estes Park.

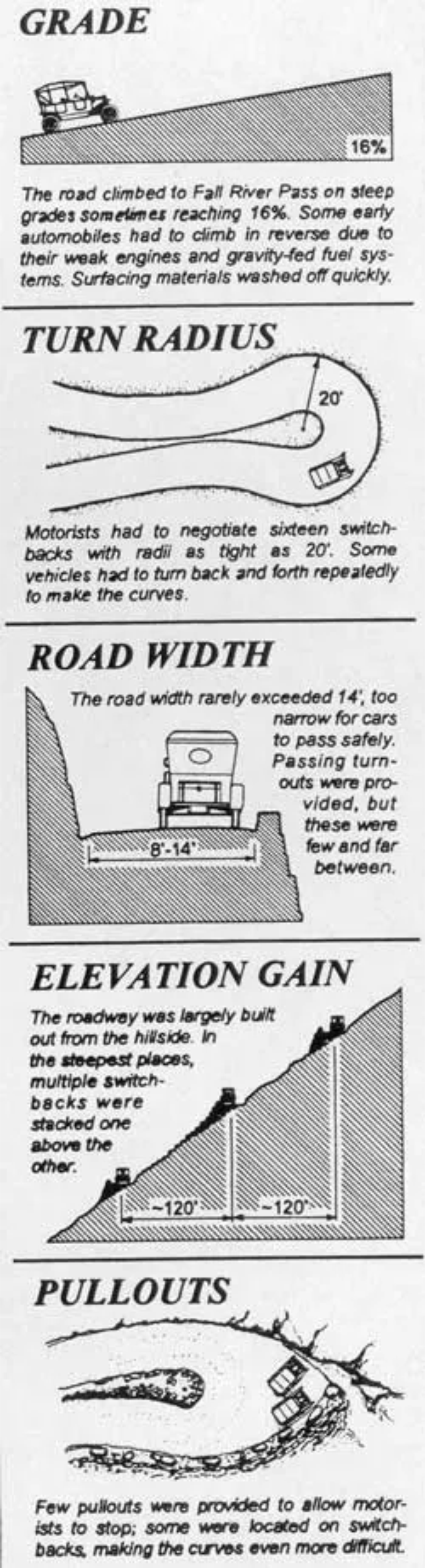

Photos and story by Barb Boyer Buck Right around July 4 every year, Old Fall River Road opens for the season. It's a very short season for this “motor nature trail,” so I encourage everyone to try it at least once before it closes in early October. It's my favorite driving tour in Rocky and every visitor I've hosted has accompanied me on this drive. Old Fall River Road starts in Endovalley, just west of the Alluvial Fan. It's 11 miles of gravel road going up a 16% grade with many switchbacks to reach the back parking lot of the Alpine Visitor's Center on Trail Ridge Road. Thus, this is a very slow drive, especially if you take advantage of the many opportunities to pull off the road and explore (which I do). This tour is perfect for those with low mobility who would nevertheless like to see the best of what Rocky Mountain National Park has to offer. Wildlife, waterfalls, wildflowers, and stunning scenery greet you the entire way driving up this road. Since this is a one-way one-lane road, going up (you'll have to come back down via Trail Ridge Road), there are several things to keep in mind. First, be sure you have a full tank of gas. You'll not be able to go any faster than 10 mph (the speed limit is 15, but I've never achieved that), and many times, you will be stuck when motorists in front of you stop to take pictures or view wildlife. Secondly, make sure your vehicle can handle rough terrain during changing weather conditions. The road is maintained, but often has large ruts, can be icy and/or wet, and is quite narrow. Vehicles over 25 feet long and/or those pulling trailers are not allowed to travel this road. I have personally seen very large vehicles have trouble with the winding nature of Old Fall River Road. You'll need to conquer any fear of heights you may have – there are no guardrails on this road and several, very steep drop-offs – the driver needs to pay close attention and not be distracted by the sights and sounds of this beautiful drive. Along the way, you will gain more than 3,000 feet in elevation before you end up at the Alpine Visitor's Center which sits at 11,796 feet above sea level. Doing anything at this elevation may be dangerous for those with heart conditions and everyone needs to be aware of other dangers such as elevation sickness, lightening, sunburn, and dehydration. Be sure to visit RMNP's safety page before heading out with anyone who may be affected by the elevation and conditions. The good news is, with proper preparation most people will be able to see some of the highest reaches and most beautiful mountainous terrain in the entire state!

For avid hikers, this road gives access to the Chapin Creek Trail, 3.9 miles through wetlands and meadows, with stunning views of the Continental Divide. There is also an option to continue on to “all summits”: Chapin, Ypsilon, and Chiquita, which is a much more difficult hike (and one I've yet to attempt!). Soon after the trailhead pullout, Old Fall River Road emerges into alpine tundra. Ahead, you begin to see the back side of the visitor's center and all around you, you see a thriving ecosystem boasting of tiny wildflowers, numerous wildlife, and rolling hills of treeless expanse. This landscape is extremely delicate and walking on the tundra is expressly forbidden. The drop-offs along this stretch are even more steep than what was encountered previously on this road, so don't pull out of traffic unless you are sure it's a designated spot to do so! After reaching the Alpine Visitor’s Center, you have several choices. You can stop and get lunch there (but no gas, but that's OK because you filled up before you left, right?), shop for some souvenirs, and original Native American art, or visit the interpretive center to learn more about Rocky's tundra ecosystem. This is also a popular bathroom stop. When you leave the Alpine Visitor’s Center parking lot to access Trail Ridge Road, you can turn left to descend into the east side of Rocky and back to Estes Park, or, you can turn right to continue to its west side and the remarkable Kawuneeche Valley. Through this valley runs the Colorado River, its headwaters originating in the high reaches of Rocky. Several trails, including handicapped-accessible ones, picnic spots, and pull- outs offer great views of the markedly different landscape on this side of the Park. The west side of the Continental Divide tends to be more lush and boasts of a stunning variety of wildflowers you may not find on the east side. There's also a good chance you will see moose in this habitat, especially in the late afternoon. If you continue on Trail Ridge Road through the Kawuneeche Valley toward Grand Lake, you will witness the devastating destruction caused by the East Troublesome Fire in October, 2020. In places, the soil became activated and wildflowers proliferate. But you will also see areas where the top soil was completely destroyed by the raging inferno and nothing remains except tree trunks, bare of all branches and needles. I always continue into Grand Lake, a quaint small town on the shores of Colorado's largest natural lake. Some reservoirs, like Lake Granby, are much larger, but this was a sacred place for the Native Americans who first traveled up what is now Old Fall River Road to hunt in the area. Old Fall River Road was completed in 1920 and ushered in the motorizing era of visitation. The grand old lodges where people came to spend the summer and recreate in the lower reaches of Rocky were eventually torn down and replaced with parking lots, pull-outs, campsites, and picnic tables. The communities of Estes Park and Grand Lake opted for more motels as Rocky began to cater to the road-trip traveler. Pro tips:

Barb Boyer Buck is the managing editor of HIKE ROCKY magazine. She is a professional journalist, photographer, editor and playwright. In 2014 and 2015, she wrote and directed two original plays about Estes Park and Rocky Mountain National Park, to honor the Park’s 100th anniversary. Barb lives in Estes Park with her cat, Percy. The publication of this work of independent and local journalism was made possible by McGregor Mountain Lodge and Backbone Adventures, both in Estes Park.

by Cindy Elkins photos by Erik Stensland As a self-proclaimed hermit, the insightful photographer and naturalist Erik Stensland is the entrepreneur behind the Images of Rocky Mountain National Park Gallery in downtown Estes Park, Colorado. He is drawn by the natural world and has a deep passion for wilderness education and preservation. As an author, photographer and program developer, his unlikely path to RMNP was filled with adventure. In 1992 he married the love of his life, Joanna. Together, they set out on a path of service in the Balkan Peninsula of Europe which included living in Austria, Bulgaria, the most remote part of Albania and eventually, Kosovo. For more than ten years he partnered with churches and other organizations to “develop job creation programs.” His efforts to build opportunities for others included developing eco-tourism, a small air service into a remote area, selling local art , and dozens of other things. When the Kosovo war hit, they started a refugee agency and when the war finished, the Stenslands moved into Kosovo to help bring cohesion and communication between over a hundred smaller agencies that were working to help the area recover from the devastation.” During this turbulent time, the Stenslands witness gun violence almost daily; so much so that Erik carried a letter in his back pocket for his wife should he be killed. One can only imagine that burn out and exhaustion would ultimately lead him to ask God for change. In prayer, he specifically asked if it could be on a mountain, have a hiking trail nearby, and much needed solitude. Two days later, a friend asked if he knew of anyone who might want to take an extended break from Kosovo and move to Allenspark, Colorado to live in the basement of their cousin's soon to be built house. Erik said yes; shortly thereafter he and wife Joanna were headed stateside. Erik recognized that he had hit bottom, needed change and his prayers were answered with a new life opportunity. He began an online master's program in organizational development and the family grew to include a son. A few years later, the Stenslands returned to Albania only to find that he was no longer needed there. Returning to the Colorado Rockies they have called Estes Park area home for over 18 years. Once settled in, Erik knew he needed a job and would have to reinvent himself. He was open to what that might be. As an observant person and avid hiker, he noticed beautiful photographic images of nature and wondered, “How do I get paid to hike?” In a conversation with a local gallery owner and wife of a successful photographer, Erik shared that he was considering becoming a professional landscape photographer. Their response was the challenge he needed to spark his next adventure. He was told it was “impossible to make a living with just photography here.” That was all it took to launch his imagination into action. This year, Erik celebrates 17 years of photographing the amazing landscapes of RMNP and the American southwest. Currently Erik has two galleries, one in Estes Park and another in Abiquiu, New Mexico near Georgia O'Keeffe's former residence. Unfortunately, the East Troublesome Fire of October 2020 in Grand Lake, Colorado destroyed the home of those running his gallery space there resulting in them moving and the gallery closing. A new Grand Lake gallery may emerge in spring of 2023. With all of his work, Erik strives to educate photographers and outdoor enthusiasts in the ethics that are needed to truly preserve our wilderness. His foundation The Alliance for Responsible Nature Photography , (Nature First Photography) leads the way in helping others understand the importance of caring for wilderness and respecting the natural environment. “Leading by example and not pointing fingers.” Erik upholds strong values when hiking, or taking photographs. He lives up to and professes seven principles listed on the Nature First website as:

Integrity has three parts to the definition: knowing the difference between right and wrong; acting on doing what is right; and, being willing to speak up, even in the face of adversity, to educate others on what is right. Erik Stensland lives a life that nurtures integrity and helps others to know how to pursue an innate passion of being in the wilderness while standing shoulder-to- shoulder with integrity. He hopes that everyone who enters into RMNP will take the time to understand the fragility of this amazingly strong place. A park ranger friend of his said that Rocky Mountain National Park is experiencing “the urbanization of the wilderness”, referring to how many visitors come and go that do not know how to behave in the wilderness. Let's face it – there are many ways to visit Rocky: a quick drive across the Park including a jaunt around a lake or visitor center and exit through one side or the other; an extended-day visit with lunch somewhere; or, you can take a deep dive into Rocky. Erik wants everyone who visits to abide by a simple understanding of respect. Respect of impact and respect of realizing where you are includes recognizing how many others will come and go beyond your visit. He welcomes others and hopes they leave the land, animals, and beauty for all to enjoy. Take a risk and turn off your phone, your music, listen to the silence and find your inner creative self. Erik's own quest for silence and solitude takes him deep into the Park as he captures each hike on maps. Every adventure, often beginning way before sunrise, each cliff and breathtaking waterfall are captured and categorized in his records so he can continue to find places that he has not been before. Erik strives to climb a new horizon with each mountainous adventure in Rocky Mountain National Park. Rocky has an allure for him; Erik said he suffers from a self-proclaimed “illness when it comes to what's said to be impossible”. He overcame the challenge of “that's impossible” to create his dream job of being paid to hike. His passion to educate others in what is needed to preserve our wilderness areas leads him to write and develop opportunities for others to explore our favorite national park. Erik hopes that his photography will be seen in a way that allows the viewer to “step back and look with fresh eyes, recognizing that nature is a gift.” When asked what some of his favorite areas or subjects within RMNP to photograph are and why? Erik responded with, “I can get as excited as a child at Christmas if I'm at a calm mountain lake with dramatic lighting illuminating jagged peaks surrounded by low clouds. Yet, I can also get very excited to find a simple scene in a forest such as aspen leaves that have fallen into an artistic pattern on a lichen covered rock. In the silence there is an opportunity to slow down, to pay attention, to forget all the other responsibilities and expectations of life. For me that opens the door to really begin to see the wonder of the natural world both big and small.” Currently, Erik is the author of seven books, has a successful online educational program and strives to work with local organizations to assist every visitor to RMNP understand where they are visiting. Erik says: “I hope that this generation and future generations will see the value of wilderness for its own sake. As humans we have this tendency to judge everything by what it does for us, the value it can give to us. That may be viewing a forest for the lumber it can provide, the minerals, water, food, or other that it may contain. Yet we as nature lovers can also do the same and see that same forest only for the recreational opportunities, views, and restoration it can provide us. I would hope that we would all come to view the natural world as having a right to exist apart from ourselves and what we get out of it. I would love it if my photographs could help us recognize its intrinsic value apart from us.” Stop by the Images of Rocky Mountain National Park Gallery; maybe he will tell you about a mountain lion encounter, hikers unknowingly sitting on a frozen elk, or about his adventures into the depths of the Park at night. Listen with both your eyes and ears as he shares photographs, reminds you to walk in the middle of the trail and educates you as to why. by Rebecca Detterline In the winter of 2017, while making plans for a hike to Blue Lake, a friend asked if I owned ice skates. Growing up in Minnesota I think every kid had ice skates, but somehow mine never made the journey to Colorado. Almost everyone in Minnesota knew how to ice skate. Whether they just strapped on a pair of rentals for the annual elementary school field trip, played hockey at the outdoor rink found in every single small town, or, like me, walked down to the nearest lake dotted with fish houses and skated clear across to the other side, it was pretty rare to make it through one's formative years without at least giving ice skating a try. Back to Blue Lake. Since I didn't have skates, my dear friend had secured a pair from someone with feet probably two inches longer than mine, so I laced them up as tight as I could and headed out onto the lake. I consider myself to be relatively athletic, but with the skates that were a couple sizes too big and Blue Lake being covered in miniature ice moguls, I looked like Bambi attempting to learn to walk on a frozen pond! How could I have unlearned such a simple skill in twenty short years? Luckily, I made it off Blue Lake unscathed and and headed down to Black Lake, which was in incredible shape for ice skating, where we skated for another hour and I felt that I was able to redeem myself as a Minnesota girl. Compared to other winter activities in the Park, ice skating the price of equipment is relatively low. Ice climbing, mountaineering and backcountry skiing require loads of specialized gear, not to mention an experienced partner, mentor or guide. I've also noticed that the dollar-to-fun ratio seems a bit questionable when it comes to snowshoes. Ice skates, on the other hand, are available at any number of sports equipment consignment shops along the front range for $50 or less. In order for conditions on the alpine lakes to be suitable for enjoyable ice skating, it seems like conditions for all other winter activities have to be terrible. Lack of snow and high winds are the recipe for clear ice up high. Ice skating is a blast, but fires are terrifying, so I will take the snow every single time, even if it means I have to attempt to clear off a 10x10 foot area with an avalanche shovel. With the exception of Lake Haiyaha, which seems to miraculously repel snow during the winter months, hiking to an alpine lake with grandiose plans to skate on smooth, clear, snow- free ice can lead to disappointment. Luckily, my friends are running around RMNP all winter, sharing photos on social media, so that I know in advance whether my lake of choice will be a glassy, ice skater's paradise or a field of dense impenetrable snow. Without an updated conditions report, it's probably best to not to make ice skating one's primary mission. Rather, plan an enjoyable winter hike, pack the skates, and treat ice skating as a bonus activity. Skate guards are essential to avoid damage to one's backpack, favorite puffy jacket, or—heaven forbid—water bladder. This risk, coupled with the bulkiness of ice skates and my affinity for a small backpack have had me seriously considering trying out the antique strap-on skates that sit atop my mantle as decoration. Although I've historically been able to find a relatively smooth spot on most alpine lakes, learning to ice skate on them is not ideal. I vividly remember a day on Sprague Lake last winter when it seemed like someone must have snuck a Zamboni unto the ice; it was that smooth! I wonder if I will ever experience conditions like that again. I'm definitely not holding my breath. For children and beginners, YMCA of the Rockies and Trout Haven offer ice skate rentals and onsite skating rinks. For those looking to givethe alpine lakes a whirl, the Mountain Shop offers daily rentals that can be taken into the Park. Although the wind is usually blowing and my ice skates are freezing cold when I pull them out of my backpack, once I start skating, I never want to stop! Ice skating in Rocky Mountain is a truly magical experience. I have been lucky enough to ice skate on Chasm Lake on a sunny day with Longs Peak looming above, so I guess that I have been lucky enough.  Adeline Williams and Rebecca Detterline skating at the YMCA of the Rocky's Dorsey Pond. Adeline Williams and Rebecca Detterline skating at the YMCA of the Rocky's Dorsey Pond. Rebecca Detterline is a lover all things RMNP. She is a wildflower aficionado whose favorite hiking destinations are alpine lakes and waterfalls. Her name can be found in remote summit registers in Wild Basin and beyond. Originally from Minnesota, she has lived in Allenspark since 2011. story and photos by Marlene Borneman editor's note: this story is pulled out in its entirety from the February/March edition of HIKE ROCKY digital magazine. For more information about the magazine visit this page Finch Lake: 10 miles round trip Elevation: 9,912 feet Elevation gain: 1,432 feet Finch and Fern Lakes are destinations I have been to many times in every season. People often ask me if I get tired visiting the same places over and over. The answer is always “no.” For me each outing in Rocky is different. Sometimes I go solo or with a variety friends, different wildlife sightings, weather, terrain, and seasons. The surroundings and circumstances change, making each excursion a unique experience. I've been surprised by fresh avalanche disturbances, high water, bridges out, snowdrifts, downed trees, a new wildflower, and fresh conversations. On January 9th I started with friends to snowshoe to Finch Lake from the Wild Basin trailhead located in the southeast corner of RMNP. Wild Basin is a place very dear to my heart. This section of the park is “wild” and packed with alpine lakes, deep flowing rivers, waterfalls, high majestic mountains, and imposing passes. Strapping on snowshoes, we started out on a snow- packed trail. Soon, we headed east, contouring the north side of a long moraine. This part of the trail is frequently icy, but that day we found deep fresh snow. As we gained the ridge and then over, we dropped down to a pretty meadow with aspen groves. In summer months, this meadow would be filled with a variety of wildflowers, but that day it was a blanket of snow. Not only did we find substantial snow but what seemed like hundreds of slash piles randomly stacked throughout the meadow. The scene evidenced the hard work of fire management staff in a fuel reduction project. We circled the maze of slash piles with no trace of the trail. It was very disorienting to be among these scattered slash piles. There were snowshoe tracks going in every direction, possibly the fire management crew or perhaps some other disoriented hiker. We were certainly not lost. We knew about where we were on the map but didn't know exactly where the trail was located. It was then I realized how much trees give definition to trails, especially in winter.  Looking west I kept heading across the meadow and then into heavy forest and whoa - I see the first trail junction signage for the Allenspark area. I knew the trail from here goes steeply up with several switchbacks to the next trail junction. It helped that the slash piles stopped at this first junction so that trail became more distinct through the stands of lodgepole pines. After a steep climb through deep snow, we came to the Allenspark Trail/ Finch Lake Trail/Calypso Cascades junction. By now it was noon and time for lunch. We all took pleasure in the stunning view of the south side of Longs Peak, Mount Meeker, Pagoda Mountain, Mount Alice, and Chief's Head. The Finch Lake trail was not broken from this point and we wisely decided to head back retracing our steps. We did not reach Finch Lake, nevertheless a worthwhile day exploring. Fern Lake: 7.6 miles round trip Elevation: 9,540 feet Elevation gain: 1,390 feet On a chilly January 21st morning my husband and I started out for a snowshoe trip to Fern Lake. The trailhead is tucked in the northwest corner of Moraine Park. In winter, this hike requires an extra .7 mile of hiking on a road to the trailhead. In the 1900s, the Fern Lake Trail Trail was used by lodge owners, hikers, horseback riders, snowshoers, and skiers. Fern Lake Lodge was comprised of a central lodge and several cabins. Weary visitors could buy refreshments and/or spend the night in the comforts of the lodge enjoying stories told by the owners. It was a popular winter destination. However, in the forties and fifties it was open only in the summer months. The lodge experienced several owners and unfortunately many pilfers and vandalism. The lodge was closed by the Park Service in 1952 and then the remaining structure was burned by the Park Service in 1976. The Old Forest Inn was another well-visited lodge located three and half miles from the trailhead above The Pool. This was a smaller lodge with several platform tents scattered to serve visitors. The Old Forest Inn was closed in 1952 and then dismantled in 1959. Now an established campsite on the site bears the name Old Forest Inn. Fern Lake Trail was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2005 to commemorate the role it played in the Park's tourism industry. 2012 brought a fire to this trail caused by an illegal campfire. The rements are still evident today. In 2013 a major flood along the Front Range also impacted the Fern Lake Trail washing out a section. Then in October 2020 the East Troublesome Fire brought more devastation to the area. The trail was closed for some time as burned down trees covered the trail, unstable standing trees, burned bridges and hot spots remained for a long period. If the Fern Lake Trail could speak, what would it say having witnessed so many early visitors in every season and surviving destruction of fires and floods? We have hiked this trail in summer and winter since the East Troublesome fire finding it very altered and very resilient. What stands out for me, besides the burned forest, is that the Big Thompson river is now very visible from the trail whereas before thick foliage hid the view. We found the trail to be easily negotiated with just micro-spikes up to The Pool.  We carried our snowshoes, so we were prepared when we reached deep snow ahead. I had forgotten how stunning the scenery is along the Big Thompson River especially in winter with icy formations in the snow-covered river with fast moving water peeking through. We first come to Arch Rocks so named for the huge granite boulders sitting upright at angles. As we walked through Arch Rocks we found several piles of elongated rounded ends “milk-dud” shaped scat and a few moose tracks in the icy trail, but no actual moose. We worked our way along the river as the trail became steeper. In 1.75 miles we reach a place simply called The Pool. Named for the deep granite bowls holding churning waters at the confluence of Spruce and Fern Creeks with the Big Thompson River. On that day The Pool was stilled by ice and snow. After crossing a sturdy bridge over the Big Thompson River the trail goes up to the right with a sharp switchback. We found the snow had drifted over the trail resulting in a steep slope. We saw others had avoided this crossing and gone straight up to contour over a small rise and back down to the trail. We did the same avoiding the steep snowbank. We quickly traded our micro-spikes for snowshoes. Little did we know what waited for us further up the trail. We crossed a large new bridge spanning Fern Creek. The bridge was recently replaced due to the East Troublesome Fire. We again found ourselves in a midst of charred trees gaining altitude at a steady rate along several switchbacks. Despite the fire scars this area still shows off a true winter wonderland with views up Spruce Creek. The higher we climbed, we encountered more huge snowdrifts across the trail. These snowdrifts made it difficult to stay on the trail. We wandered up and down and around these huge snowdrifts and finally got to a spot we thought was the long switchback to Fern Falls. We snowshoed towards the sound of fast- moving water and then looked down at the river below but no falls. We backed tracked a bit and then climbed back up to what we were sure was the switchback above the falls. The terrain became one large steep snowdrift! In each direction no standing trees just open burned forest. Again, a very disorienting situation. We crisscrossed several times to the area around Fern Falls, but no falls. We had not seen anyone all day and then suddenly two men appeared coming toward us. After a greeting they explained they did not find Fern Falls either but had arrived at Fern Lake via GPS. We all commiserated how different the landscape appeared with the huge snowdrifts and burned forest. As the two men headed down, we found a perfect overlook for a well-deserved lunch. It was a humbling spot overlooking Forest Canyon and Tombstone Ridge. We are kind of feeling discouraged by not reaching Fern Lake or even Fern Falls! Suddenly, it begun to snow heavily. Laughing out loud feeling a bit silly, yet acutely aware of our charmed day we took our time eating lunch appreciating the location (wherever that was?). “It's not about the destination, it's about the journey.” This familiar quote came to mind after these two recent snowshoe trips. I thought “It's ok not to reach the day's goal.” There is no measurement for experiences, friendships, and good old-fashioned exercise in the great outdoors.  Marlene has been photographing Colorado's wildflowers while on her hiking and climbing adventures since 1979. Marlene has climbed Colorado's 54 14ers and the 126 USGS named peaks in Rocky. She is the author of Rocky Mountain Wildflowers 2nd Ed, The Best Front Range Wildflower Hikes, and Rocky Mountain Alpine Flowers. Story and photos by Marlene Borneman It began innocently enough, in 1974. l came to Colorado for a summer job at the YMCA of the Rockies in Estes Park. I arrived from New Orleans (yes, below sea level) in mid-May of that year and, being a proper young lady from the South, l wanted to make a good impression on my new employer. l wore a sleeveless silk dress (rather short as I recall), stockings, and the cutest little heeled sandals you ever laid eyes on. It was somewhere around 30 degrees and spitting snow. It turned out to be one of the scariest days of my young life. All l could think was, "l have made a terrible mistake!” Fortunately, those feelings didn't last all too long. Once over the cultural shock of my summer home, I seeded into the rhythm of working and learning about a phenomenon called "hiking." I was fortunate to meet Dick Chuttke. He was a retired gentleman, a YMCA member, and a Colorado Mountain Club member who enjoyed hiking with the YMCA groups. Ironically, he suffered from acrophobia, an irrational fear of heights. He became my climbing mentor for the next 20 years; he taught me how to be fast and careful at the same time and instilled in me the ethics of Leave No Trace before it was popular or common. From short silk dress to summits, my progression came fast. By the end of that summer, I had climbed most of the major peaks in Rocky Mountain National Park. Having graduated from college, l decided to stay in Colorado. You might say the rest is history, but it was not that simple. I lived in Estes Park for 12 years and climbed in the park year-round. I found myself focused on the major peaks, and their different routes, with a few new peaks thrown in now and again. Then came a career move away from Colorado; to say I began grieving would be an understatement. But, by 2001, I had returned to live full time in Estes Park. After completing 54 fourteeners in 2005, I was hit with the pain of guilt. I imagine you all know what it's like to ignore a friendship. This was worse: it was like neglecting your own husband. After all, Rocky Mountain National Park was now in my backyard. I began to rekindle my relationship with Rocky, and started studying the map with new interest and curiosity. When you get down to it, though 35 years had passed Dick's spirit motivated me to complete the 126 named summits in Colorado's crown jewel. This was the project I needed to turn neglect into passion. First, I carefully laid out the list. There were 35 peaks in Rocky I hadn't yet climbed. By the summer of 2009, I had only three to go. Then reality struck me hard. The final three were The Sharkstooth, Hayden Spire (both Class 5, technical climbs requiring ropes and equipment) and Pilot Mountain (a difficult, though less technical, Class 4 climb). Had I set myself up for this? Shouldn't the last peaks be easy, like Estes Cone or Twin Sisters? I hadn't climbed anything beyond Class 4 in years. I lost some sleep, talked incessantly to my husband, and consulted every book and person whom I thought could set my mind at ease. Then I came to the realization that the final three were meant to be my grand finale. I needed a challenge; I wanted a challenge. I needed to gain my confidence back on the rope; I needed a plan. It felt like I needed a lot. The Sharkstooth was the first of my final three and, as it turned out, my most challenging climb in Rocky. My climbing partner and I left the parking lot at 3:45 a.m. I once read that eighty percent of success is just showing up. I liked my chances. The sky turned cloudless: a deep blue, Colorado morning without a breath of wind. We would be climbing the East Gulley Route (5.4). The first pitch was going easy enough on ledges, until we came to a short, but very exposed traverse. I watched my partner go across with ease up to a small crack, out onto a smooth rock face, then scramble up another crack. Traversing the ledge looked feasible but when I came to the first crack, I just couldn't visualize the move. I stared at it for what seemed like an eternity. Here I was, committed to this menacing climb, and the first move was proving to be baffling. The staring must have helped. Finally, it all came together and it was over, behind me. I was sweating like a pig. Good thing I had given up that silk dress. Things were going smooth until the crux: a wall of 60 feet, extremely exposed. Once again, I was paralyzed. I found myself looking at this wall, caught in my own world for endless amounts of time. I had watched my partner climb straight up with ease. Finally, I took a deep breath and let it out slowly. I knew I needed to move quickly; no hesitating, just go. I stepped out onto the wall and got my fingers into the crack, trusting my climbing shoes to hold onto what seemed to be nothing and scampered up. Though my stares felt eternal, my moves seemed mere flashes; I was on top of the cliff. As I climbed toward the summit, tears were in my eyes. This was what it was about: I hadn't gotten here because of a list, but because I had taken a risk. Ultimately, I reached the summits of the final three with a smile from ear-to-ear. I found myself enjoying these peaks more than I imagined. I will forever remember the air beneath my feet, the sudden flight and song of finches above my head, the simultaneous sense of inner relaxation and burst of excitement, and the incredible sound of the silence around me.  Rappelling down Hayden Spire in 2009. Rappelling down Hayden Spire in 2009. You may ask, is there anything left of that southern girl from 1974? My father was a riverboat captain, checking catfish lines across the river while trolling for shrimp in Lake Pontchartrain at 5 a.m.; he lived with patience, endurance and perseverance. I gained these traits from him. Maybe this is why I adapted so well to the mountains and persevered to the top of 126 of Rocky's best.  Marlene has been photographing Colorado's wildflowers while on her hiking and climbing adventures since 1979. Marlene has climbed Colorado's 54 14ers and the 126 USGS named peaks in Rocky. She is the author of Rocky Mountain Wildflowers 2nd Ed, The Best Front Range Wildflower Hikes, and Rocky Mountain Alpine Flowers. |

Categories

All

|

© Copyright 2025 Barefoot Publications, All Rights Reserved