|

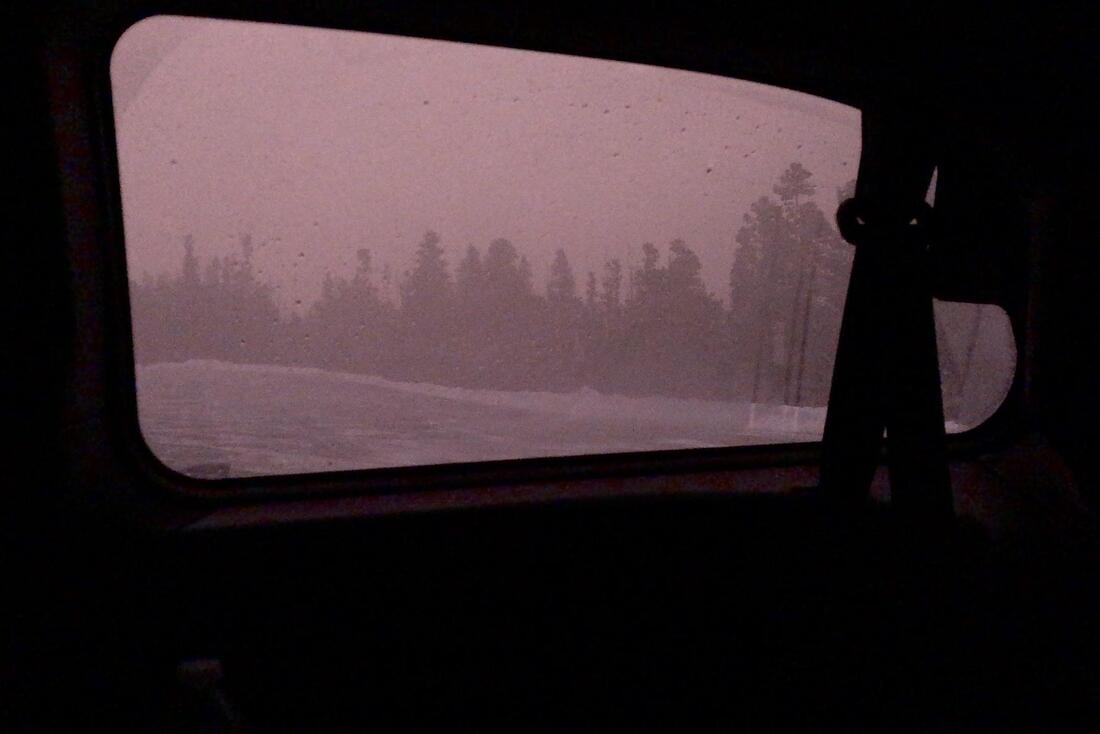

Guest submission by Nevin Dubinski As someone who has spent nearly his entire life in Missouri, visiting the Rockies is a treat. As we were growing up, my parents would take us west once every year or two and each time, I would learn to love it more. But of course my view of the mountains was insular, only visiting during the summer months and omitting the harsh winters that I heard so much about. I began to dream of reaching the peaks once the snow had fallen and I could partake in even wilder adventures. After years of dreaming my opportunity finally came this December when my friend Nick and I realized our finals week was free of exams. We rushed to complete what work we did have and hit the road on Monday, Dec. 13. The only unfortunate thing about the excursion was that it wouldn't technically be winter. The plan was to spend three nights near Black Lake in the backcountry of RMNP off of Glacier Gorge trailhead. The prospect of a Park free of timed-entry permits and camping fees was enough to make me reconsider my rule of sticking to less-visited National Forests and wilderness areas. On top of the solitude, the trip would only be 11 miles round trip, a distance Nick and I figured we would handle easily. Nevertheless, we knew we only had a few days to get everything together. We vacuum-sealed our own backpacking food, waterproofed nearly everything and solicited gear donations from friends and family. We needed snowshoes, thicker pants, better trekking poles and dozens of smaller things for a cold weather experience. By the end of it, at least eight people from both Colorado and Missouri had contributed to the cause. On Tuesday we reached the wilderness office at Beaver Meadows to some surprise from the staff. The lady behind the counter inspected us like the out-of-towners we were, bright-eyed and oblivious to what was to come. We assured her that we had all the necessary equipment to be a little less than miserable on our expedition and she reluctantly filled in our permit. That night we slept at the trailhead in our minivan, excited to hit the trail as early as possible. We woke up to a calm yet uneasy scene. The sky was tinted a soft pink and the sun was nowhere to be seen. Not ten minutes later the wind storm came in. 100-mph gusts jostled the van in a way only comparable to a hurricane. Walking to the bathroom involved leaning as if the world were tilting beneath me. We later found out that this same storm blew through Kansas with such severity that they shut down sections of I-70. Knowing that setting up a tent in triple-digit gusts would prove impossible, we decided to wait until the next morning to depart. Much to my dismay, the only time we left the van was for a short walk to Alberta Falls, about .6 miles up the trail. This short hike was our first official introduction to the Rockies’ mean side. The wind spat snow at us, temperatures sat well below freezing and the sky remained ominously gray. On Thursday we finally hit the trails, loaded down and elated by the near tropical weather. The sun beat down and brought new life to our steps. A few early risers had forged a clear run for us and we moved with relative speed given our weight. Aside from Nick occasionally complaining of cold fingers, we made it the 2.5 miles to Mills Lake without a hitch. We ate lunch overlooking the vast stretch of ice but didn't hang around for too long. A late start meant the sun was already retreating behind Thatchtop Mountain to the west. The trail past Mills and Jewel Lakes was non-existent, leaving us with the tough task of wading through deep cover. Hiking across the frozen lakes saved us tremendous time, but reaching the final junction before Black Lake was slow moving and brutal. When we finally did reach it the sign said just 1.2 miles further. The canyon began to narrow dramatically after this but we made it only .3 of a mile before we called it a day. Everything past the lower lakes was a mix of up and down, leaving us exhausted after six hours of uphill progress. Our camp was together by 3:30 pm, just in time for the sun to disappear and the temperatures to drop dramatically. We spent the rest of the night in the tent recounting the day and its scenery. When I went to scoop a bit more snow for boiling I witnessed one of my favorite views. The moon shone brightly against the surrounding walls and the gorge made no noise. They rose like blue giants in the light, still visible enough to count the trees on their ledges. It was surreal for such a vast place to be so quiet. As night wore on we listened to the wind pick up and screech overhead. Thankfully we were protected in our gully a few dozen yards off the trail. Large flakes came down in force, rhythmically striking the rainfly and lulling me to sleep at an early hour. The next bit of excitement came at 1:30am when I was awoken by a firm shake. Nick whispered at a near undetectable volume that something was outside the tent. I listened intently, and in between the symphony of falling snow I heard the distinctive crunch of snow, accompanied by the sound of sniffing. Nick white- knuckled his bear spray while I gripped my knife, and before too long we heard it lumber back into the night. The next morning we were greeted with several inches of fresh snow, covering any sign of the visitor. Everything was frozen solid from my contact solution to my underwear. Nick looked at me in protest and said he was ready to leave. I said he was free to leave whenever he liked, not unlike a pirate telling his captive he was free to go for a swim. I was going to see Black Lake at least once, even if it meant hiking the last mile alone. I strapped on my snowshoes and packed light. Only a few tools and some emergency supplies made the cut. The half liter of water I brought ended up being useless as the cap froze shut in the single-digit temperatures. While I was preparing another snowshoer passed our site headed for the lake, but returned just 20 minutes later to proclaim that his toes were going cold. He warned of deep drifts and unforgiving winds about a quarter-mile short of the lake. Nevertheless he said I should give it a run given my determined look. I took off up the hill, following the path he had cut for me. It became immediately clear that our early stop the night before had been the right call. The final mile was a grueling marathon through knee-deep snow while gaining several hundred feet in elevation. It took me half an hour to reach the obstacle the man had been referring to. His tracks ended at the base of a 60 degree slope, barren of anything but two feet of powder. In my first attempt I tried a direct approach, but was turned back by the impossible grade and fresh powder. I quickly reevaluated and decided to take the longer route around its edge which angled at a mere 45 degrees. After fighting it for nearly 20 minutes I knew I was in the home stretch when I reached the top. The trees broke in the distance and McHenry's Peak began to fill my southern view. My arrival was imminent. The only trail marker left was frozen Glacier Creek, which I would soon learn was not so frozen. The final pitch was Ribbon Falls, a meandering stretch of ice just below the lake which served as a perfect beginner climb. I dumped my bag and snowshoes just before the falls and made my way up the frozen slope with my ice axe and crampons. Within minutes I was making my way through the waist-deep snow on the banks of Black Lake. There was no evidence of humans, no animal tracks, or even a plane overhead. It was just the mountains and I. Directly across the lake was the largest column of ice I had ever seen, an uninterrupted sheet that traveled the final thousand feet to Frozen Lake. Sitting there in the snow I couldn't help but wonder how I might traverse it. Unfortunately I had told Nick I would be back within the hour. I said goodbye to Black Lake, confident I was the only person to have visited it that day. As I negotiated my way back down Ribbon Falls, my foot plunged into a free flowing section of the creek that had hidden itself under a foot of snow. My foot stayed dry but the slushy mix instantly welded my crampon to my boot in a bond that proved nearly impossible to break. Aside from this misstep I made my way back down the creek without incident, exuberant that I had witnessed such a beautiful view in solitude. When I reached the tent I informed Nick that he was no longer being held against his will. He had told me that morning that he had seen everything he needed for that trip, and after my final trek I was inclined to agree. We quickly packed and made our way back down to Jewel Lake. As we rounded the switchbacks near Alberta Falls in the final mile, a full moon stood proudly over Estes Park, accented by the pink and blue gradient of a Colorado sunset. The trip was one of setbacks and learning experiences, but we still managed to persevere long enough for at least one of the three nights I had hoped for. Nick and I found joy in even the fiercest conditions and I fulfilled a lifelong dream in the process. Although Nick may have been scared off for a bit, and rightly so, I'm certain I'll be back for far greater challenges in the future. Despite my inexperience I can confidently say this: Those looking for a slice of isolation should know even the most popular trailheads can offer a unique and unmolested experience come winter.

1 Comment

Simon Vogt's vlogs of his summit of Longs Peak in September, 2021, and above Dream Lake earlier this year. story by Barb Boyer Buck, photos & videos by Simon Vogt Colorado resident Simon Vogt has summited 57 of the state's 14-ers (mountains over 14,000 feet in elevation); he only has one left: Culebra Peak in the Sangre de Cristo range. Mountaineering in the high peaks of Colorado's Rocky Mountains has become a metaphor for the new life he is developing for himself: one of sobriety and focus. “The summit is the goal, but it's not the reason,” he said. Since choosing sobriety three years ago, Simon has turned to high places of Colorado (and other states) for solace and a sense of accomplishment. This attitude hasn't been Simon's strategy his entire life, however. He was born and lived in Germany for eight years after which his family moved to New York. He moved to Colorado for college in the early 1990s. “Colorado is the first place I developed a real interaction with the outdoor world: climbing, hiking, and mountain biking,” he said. But he also encountered tumultuous problems with the law, alcohol, and drugs. His naturally impulsive and reckless nature got him into some real trouble while he was using and drinking. “I almost died many times,” he said citing a week-long coma from a heroin overdose in 1994 and daring mishaps while bouldering with friends. “I was also shot at several times and stabbed as a result of poor choices,” he said. “It was the world I was living in at the time.” A couple of years after that, he almost died again. “I quit drinking after I went to the emergency room for pancreatitis. It felt like I was on my deathbed.,” he said. “Being able to get up from that bed and walk out of the hospital was the beginning of a new start, and a miracle.” He faced an immediate test right after getting sober; his boss died, he got evicted from his apartment, and his girlfriend left him. He started living in his truck. In those uncertain days, Simon started taking walks at night because he couldn't sleep. “I got back into hiking more and more after that,” he said. Simon likes to hike alone, especially on his longer adventures, but takes care to be sure he is prepared. His naturally impulsive personality no longer turns reckless, as he cares for his well-being now. He pushes his limits, but he doesn't exceed them. “It's nice to be alone, but running into someone is reassuring,” he said about seeing others on the trail. “It's a secret link between you and them, a camaraderie of being with someone within a 10-mile radius. “ “Mountaineering is very peaceful, meditative, and an inner experience,” he said. “There's a dichotomy between being deep inside of yourself, examining your consciousness from a little further back in your mind, juxtaposed with the physical challenges of the outside environment. “Emotionally, it puts me very much at ease, I go out there for the feeling of solitude, to get more of an inner connection by having that outward experience. This is when I thrive and feel alive.” On his adventures, Simon also finds he can communicate quite easily with what he understands as God; this has been one of his touchstones since achieving sobriety. “Turning your life over to a higher power, trusting that things are going to be OK, any way it turns out-- that is the key,” he said. “You have to let things go and not stress or be anxious about things you don't have any control over, like trail conditions or the weather, or what you encounter at work. “Once you see yourself as connected to a greater path in life it's easier to enjoy the moment.” The gratitude he feels while on these trips reinforces this connection. Suddenly, he is no longer the outcast and trying to fit himself into a shape society asks him to fill. These days, Simon works as a freelance contractor and carves out considerable time for traveling and mountaineering. While standing on these mountaintops alone, he sees these moments as wonderful gifts that are uniquely for him. “I experience a rush of endorphins, that weird chemical euphoria that I used to seek out artificially,” he explained. “I become grateful for being a human on this planet, for having legs to get me to the summit.”

Simon is continuously honing his preparation for hiking; after every trip he has figured out a way to lighten his pack a bit more and reduce the amount of water he carries. “When climbing a mountain, you should only expend about ¾ of your energy climbing to the summit, you need to reserve about ¼ for the return,” he counseled. “You need to find your own path and whatever path that is, keep moving. Keep moving even if it's not forward, sometimes you have to go sideways. As long as you keep going – take another step and then another and another. “I apply the same things in hiking that I apply in recovery; it's not necessarily getting to the mountain top that's the important thing. In life, you're never like 'I made it!' You never truly reach that point. You're never done, it's never over. Once you get to the top you have to get back down.” Taking responsibility for his actions, along with expecting setbacks on the journey is essential to Simon's new outlook on life. “If you can use those setbacks and disappointments not as a discouragement but as a motivator, you succeed,” he said. “They are learning experiences and that's what it takes to improve. You have to expect to have problems and run into unforeseen things – in life and in hiking.” from the October 2021 edition of HIKE ROCKY magazine story and photos by Rebecca Detterline The snow at Thunder Lake was definitely deeper than anticipated on a recent attempt at a few remote peaks in Wild Basin. It quickly became obvious that our original plan would be thwarted by the slick conditions resulting from the first snowfall of the season. Knowing that our hike would be considerably shorter than we had prepared for, my two girlfriends and I hopped from rock to rock, following the steep trail that leads hikers from Thunder Lake to Lake of Many Winds, occasionally post-holing into calf-deep snow. Our feet were already cold and wet, and each step into the fresh snow packed a bit more snow into our sneakers. Visibility was poor and it would have been unwise for us to travel to the high and exposed peaks of Wild Basin with no traction or mountaineering equipment. However, moments of sunshine and breaks in the clouds revealing views of Longs Peak and Mount Meeker made our chilly feet nothing more than a small annoyance. Winds were relatively low and we knew we were only a mile and a half or so from the dry Thunder Lake Trail. ‘Have you ever been up Mount Alice?’ I asked my friend Kirby. She hadn’t. ‘How about Boulder-Grand Pass?’ Negative on that one as well. Unbeknownst to me, the trail that we were hiking on was completely new to her! She had never traveled past Thunder Lake toward Lake of Many Winds. While I love to stand on a summit or dip my toes in an alpine lake, I am definitely a hiker who enjoys the journey as much as the destination. I will not hesitate to hit the trail in the drizzling rain or on a day with a 90% chance of precipitation knowing that my original objective is likely unattainable on that particular occasion. There are so many worthy destinations at and below treeline in RMNP and I am always happy to don a rain jacket and gloves and revisit Ouzel Falls or Lake Helene or any other number of places I have seen about a million times. That being said, Kirby’s revelation that she had never been to Lake of Many Winds absolutely made my day! ‘You only get to see a place for the first time once!’ I beamed and we plodded up the last half mile of trail to the aptly-named lake, taking in the views of the high peaks surrounding us while Thunder Lake glistened below. This snowy hike in glorious Wild Basin was one of many opportunities this summer to share my favorite places with people who had never seen them before. I am not quite Jim Detterline-level when it comes to revisiting a place over and over. However, I am pretty sure that I hold the world record for most ascents of Eagles Beak. I have no idea how many photos exist of me in front of Ouzel Falls, but it has gotten to the point where I politely decline friendly bystanders’ offers to take my photo there. I think I have every season, every type of weather and every time of day covered. As much as I love visiting these places that have become like old friends and constants in times of uncertainly, the real joy comes from sharing these gems with others. One summer I stood on top of Longs Peak seven times, each time with folks who had never been there. I don’t anticipate another season like that, but I am always up for sharing my favorite lakes or remote summits with friends who are excited to see them. There are plenty of destinations in RMNP that I have not visited. I am not the type of person who needs to stand on top of every scree-laden summit in the Never Summer Range. I don’t have a checklist of destinations that I am hell-bent on reaching. I don’t know how many times I’ve scrambled up Pilot Mountain or The Cleaver. I do know my favorite destinations so far, though, and I tend to return to them year after year. While I enjoy revisiting these places with my regular hiking partners, the greatest joy always comes from showing someone a place for the first time. Being able to take my friends to places they have never seen is an honor and a blessing. Traveling safely through RMNP is a learned skill and I have certainly been on the receiving end of guidance from those more accomplished than myself. This summer I was blessed to traverse Blitzen Ridge to the summit of Mount Ypsilon. Thanks to an experienced partner, I didn’t have to worry about route finding and I was able to relax and enjoy the views of Spectacle and Fay Lakes from the Four Aces. I’ll never forget the first time I walked across Broadway Ledge on Longs Peak, tied into a rope and plucking out protection as I meandered toward Upper Kieners. I never could have guessed that parry primrose grew on that grassy ledge that appears so cold and rocky from afar. Any day spent in the mountains of RMNP is a gift, but the best views I have found are the ones standing alongside a friend who is seeing a place for the very first time.  Rebecca Detterline is a lover all things RMNP. She is a wildflower aficionado whose favorite hiking destinations are alpine lakes and waterfalls. Her name can be found in remote summit registers in Wild Basin and beyond. Originally from Minnesota, she has lived in Allenspark since 2011. |

Categories

All

|

© Copyright 2025 Barefoot Publications, All Rights Reserved