|

story, photos and video by Lincoln Chapman Timber Lake Trail Type: Longer Hike Trailhead: Timber Lake (west side of Rocky) Trailhead Elevation: 9,054' Destination Elevation: 11,088' Total Elevation Gain: 2,060' Total Roundtrip Miles: 10 I'm not sure I've ever hiked a more adequately named trail in recent memory. I'm also fairly certain that I hadn't hiked this unprepared in several years. I hope to do the journey that was Timber Lake Trail justice with this piece. My hope is to explain the dangers, lessons and pitfalls my friend and I found along the path. I really hope this because I wouldn't want anyone else to have to find them for themselves. It was one of those adventures that's only really fun when you live to tell about it. Somebody yell “Timber!” (and mud, and snow, and scat and stones) Timber Lake Trailhead is located on the west side of the Park, closer to Grand Lake than Estes park. The majority of guests enter RMNP through one of the east entrances, meaning they would get the pleasure – and some would say honor – of driving the majority of Trail Ridge Road to get to this trailhead. It's one of the most beautiful drives in thecountry and is built along much of the original Ute trail. It's an amazing drive and a great time sip coffee, hydrate, and eat to fill up before the hike. If you are entering from the Grand lake entrance you will experience less of the views provided by elevation elevation gain. No worries, though – my buddy and I passed at least a dozen buck elk with velvet antlers and two moose on our drive beyond the trailhead toward Grand Lake. The tunes were so good when we first pulled up to the trailhead parking lot, so we drove a bit further and looped around to hear a couple more songs. That action alone admittedly sets the stage for two twenty-somethings vibing too hard and planning too little. We were bangin' our heads out of the window to the Kingston Trio, creating a new boost of false confidence with every song. The first sign we saw at the trailhead indicating how difficult it might be (and the first sign we ignored) read “Active Landslide Area.” I’d heard of some flooding from the Colorado River on trails nearby, so I had a little bit of cautious restraint in the back of my head. However, we should have taken the time to drive to the visitor’s center nearby, to gather any information on the current status of the Timber Lake Trail. This was costly ignorance on my part; but we felt on top of the world coming down from Trail Ridge's apex. We didn't do much other than giggle at the warnings of landslides. The trail runs about 5.3 miles to Timber Lake. It wasn't the lake's timber we needed to worry about, though. We reached our first obstacle at mile marker two: the landslide zone. It ran directly across the path, laid out in a pick-up-sticks style display of fallen trees. It was a bit of a maze just to get through and on top of that. It's remarkable how slick a fallen tree trunk can get. The possibility of a new landslide was our first fear but the wreckage of recent ones were what we had to face. One wrong step and it could, “take our love and take it down.” We maneuvered our way through the logs as slow as we could and high-fived on the other side. “Pfft, all downhill (metaphorically) from here” or something along those lines was certainly spoken. Never taunt the mountains with a sentiment of “pfft,” they will be happy to play that game. We made our way through two miles of lodgepole pine and changed the amount of layers we were wearing about five times in that stretch. It was cold, as early summer has been in the Park. Every half-mile would lead us to taking our jackets off and sipping water, but by the time we were ready to trek again we'd be a bit chilly. The high of the day was predicted to be 48 degrees and it was roughly 7a.m. at this point. The forest is dense on this hike. It feels something like what I refer to as the “woods” back in my home state of Tennessee. “Woods'' are hard to come by in much of the east side of the Park. The west side, in particular Timber Lake Trail, is quite different and mysteriously thick. Mysterious in the sense that you really don't have much of a deep look into what lies, breathes or eats beyond the trail itself. Noises seem to circle, bounce and echo. We hiked with bear spray as I would always suggest. It's much better to be prepared. Wow, there was one thing we did prepare. On one of our water breaks, we sat catching our breath when I heard a growl and he heard a snapping branch. It was just one sound – we just interpreted it differently. We jumped up in Shaggy-and-Scooby- spooked fashion. We grabbed the bear spray and continued to move forward, alert. Again! He heard a big snort and I heard a massive flapping of wings. One noise freaked out both of us, letting our minds get the best of us. We passed what appeared to be scat from a big cat just a half mile or so before, so that certainly wasn't helping. Moments later we both turned our heads in sync, noticing motion in the leaves. There it was. A tiny little grouse hopping along and then flying away. His wings made the loudest echoes, snorts and growls ever, ok? The next mile or so was pleasantly uneventful, but it was steep. We had plenty of water which was a great thing because the third quarter of this hike is very taxing. It's the kind of steep that's gradual, seeming to never end. It’s just enough to wear you out, steadily. As we climbed, we became more aware of our breath. Partly due to the upward slope, and partly because our breath was becoming more and more visible as the air got cold. Snow patches started emerging on our left and our right and then little by little in the middle of the trail. We scampered across a couple six foot long snow piles and felt fine about it. We didn't need snowshoes for any of those, just a burst of energy to get across quickly. Nobody wants wet socks four miles into a 10-mile hike. Snowshoes would've come in handy about a third of a mile away from the lake itself. Like, really handy. It's amazing to me that my friend and I trekked through the snow without proper footgear. The spurts of snow turned into deep accumulation covering the entire trail. We wouldn't have been able to stay on course had it not been for the footprints a brave hiker left before us. We kept our gaze forward and upward toward the peaks, under which was Timber Lake. We followed the path of prints and kept moving forward. The inches of snow that we had begun to master didn't stay at that depth for long. No, to be honest, I'm uncertain just how deep the snowpack went. In one heavy step at one point, I fell straight through down to my waist. I'd really like to believe that was the deepest it got. The timber we had contorted through at mile two was now beneath us, covered in extremely sketchy snow. We decided to take a break from the snow and try something easier. Just left of the footprints, we began stepping from stone to stone. These were large boulders laid out in the most random patterns and heights. We carefully hopped from one to the next, trying to avoid the slick ones. We had to climb a few and use all four limbs. We reached a peak among the stones and saw a portion of the end of the trail, somewhere beyond and through the trees. There weren't any more stones, just trees and snow ahead. We hopped back on to the trail (assuming the footsteps were following it) and powered through the snow. We were in shorts and sneakers trudging through the snow up to our knees. We were so close. We powered through the brush and arrived at Timber Lake. We stood, huffing and puffing and taking it in for several minutes before saying anything. Our adrenaline had been pushed to new extremes on the way, and we both knew what the other was thinking. We shared a moment of silence and appreciation. We hydrated and replenished and laughed at our stupidity. It's easy to laugh at your own stupidity on the other side of it. Thank goodness we made it to the other side unscathed. The lake was still frozen for the most part, and there was tons of snow along the mountain bowl that encapsulates it. The light hit the snow so insanely bright up there, we joked about seeing a new shade of white. The elevation made for wild cloud movements. The clouds literally rushed above the lake; stormy but unthreatening. The shadows moved across the snow and the mountain just as fast. It was magnificent. Magnificently chaotic were the clouds and our experiences that day. We enjoyed the lake for a bit and then prepared to head back. We were more motivated than ever to start the hike back with the most difficult portion knocked out first. Our legs were beginning to feel like Jell-O and our patience was starting to wear thin, so we decided the stones weren't in our best interest on this go. We rushed through the snowpack. We found patches that only took our sopping wet feet an inch or so down into the snow and took other steps that shot our legs down to our knees in the cold. We made it through and the began the now-downhill stretch toward the scary noises. We were at the point of our day where the feeling of being “over it” on a hike was welcomed. After pushing through that stage, the feeling of accomplishment set in. We made it back to the first pile of fallen timber and laughed at how easy it felt compared to the rest. The hike came to an end and we wrung out our socks. It was the ultimate feeling of relief. Take it from me: please do your due diligence and research your hikes before you go. Stop by the visitor’s center and hear from a ranger themselves just what to expect. My buddy and I were lucky to have made it through without a twisted ankle at the very least. We laughed about our stupidity the entire drive back to Estes Park. I'm glad to have experienced the hike; I hope it serves a lesson to myself and to anyone reading as well. Timber Lake trail humbled me, I loved it.  Lincoln Chapman grew up in Nashville, TN, and is 26 years old. He idolized football his entire adolescence, which led him to a small university in Texas where he was finally able to scratch that itch at 22. After school, he started traveling, beginning with Los Angeles, where he started commercial acting and modeling. After a handful of stints in Southern California, he began traveling in his van, chasing any gig and any opportunity. He moved to Estes Park in June, 2022 where he serves wine and is pursuing his writing career. Catch him in the corner of a local watering hole jotting or doodling away on paper. The publicaiton of this piece of original content was made possible by: Ram's Horn Village Resort, Tahaara Mountain Lodge and Twin Owls Steakhouse.

0 Comments

story and photos by Marlene Borneman this story was included in the 2023 Snow Play edition of HIKE ROCKY magazine “You're off to good places, today is your day. Your mountain is waiting so, get on your way.” - Dr. Seuss A spot with deep roots for winter adventures within Rocky Mountain National Park is long-loved Hidden Valley. At 9,240 feet of elevation and thick with Engelmann spruce and Subalpine fir, this narrow valley offered enjoyment in the snow long before it became known as a downhill ski area. As early as the 1930s, locals skied old logging skids and started make-shift runs. According to his book, Recollections of a Rocky Mountain Ranger, Jack Moomaw managed the National Championship Ski Races at Hidden Valley in the winter of 1937. The Colorado Mountain Club also enjoyed many ski and snowshoe outings there in those early years. The Hidden Valley Ski Area officially opened in 1955, providing ski lessons and rentals, as well as a cafeteria, lodge, an ice skating rink and daycare. Hidden Valley certainly filled a niche for locals and the Front Range communities. Local schools took advantage of Hidden Valley and loaded school buses with students for a day of skiing. The last season for the facility was 1991, when operations closed due to financial losses, lack of consistent snow conditions and the I-70 corridor opening access to larger ski resorts. All that remained were materials salvaged to construct the current warming hut and restrooms. Estes Park local Brad Doggett was part of the Hidden Valley Ski Patrol from 1979 to 1987. According to Doggett, there were no groomed trails or modern snow-making equipment when he started work at the ski area. What he appreciated most was the family- focused atmosphere for visitors and staff. Hidden Valley Ski Area provided local jobs and a gathering place to socialize with like-minded people and will always be close to Doggett’s heart. Hidden Valley is still a thriving location for a range of winter activities. Sledding is a popular activity for families and the only place within the park where sledding/tubing is permitted. Children and adults of all ages spend many hours tramping up the hills and swishing down on sleds and tubes. Backcountry skiers, snowboarders and snowshoers are also fond of the recreational opportunities at Hidden Valley. Ski runs from 30-plus years ago provide trails through the heavily forested terrain. The slopes west of the sledding hills are a perfect place to learn and/or practice backcountry/cross-country skiing and snowboarding. The Colorado Mountain School schedules many ski classes and avalanche courses on the higher slopes. Park Rangers conduct SAR (Search & Rescue) Training at Hidden Valley. In 2016, an avalanche beacon training park was installed at Hidden Valley to be used by the public and as a vital part of training for park staff. The purpose of the Beacon Hill is for skiers to practice their transceiver location and probing skills in case of an avalanche. This free service encourages the public to practice avalanche safety. A shovel, beacon and probe are essential avalanche rescue tools and should be carried by all backcountry skiers. (also, see last edition's story, Winter Safety in the Backcountry ) Walkers take advantage of the winter's beauty here. Picnic tables are in place for both summer and winter picnics. Building a snowman is a delight at any age. Many folks visiting from warmer states or countries are thrilled to experience sparkling snow for the first time. On winter weekends Hidden Valley is staffed by VIPs (Volunteers in Parks) fittingly designated “Sled Dawgs.” VIPs help folks locate sledding slopes and ski trails, open the warming hut, provide Park information, and assist in getting medical attention in case of accidents. The goal of a “Sled Dawg” is to provide information on “snow play” fun and safety at Hidden Valley. The Junior Ranger Program is a great addition this winter at Hidden Valley. Park Rangers present a variety of learning opportunities to all ages. Explorer bags equipped with binoculars, magnifying glasses, temperature gauges and informational pamphlets are available to future Junior Rangers. Rangers gladly answer questions about Rocky's wildlife, weather, geology and much more.  Hidden Valley is the perfect place to practice new skiing skills! Hidden Valley is the perfect place to practice new skiing skills! Be aware there are dangers in sledding, skiing, and snowshoeing in a wilderness area. Sledding accidents far outnumber accidents among skiers or snowshoers. According to Mike Lukens, RMNP Wilderness/Climbing Program Supervisor, years ago there were five ambulance runs from the sledding hill in one day! VIPs inform visitors of sledding boundaries, to be mindful of other sledders, and to remind them to walk up the sides of the sledding hill rather than the middle. These simple tips may help visitors avoid accidents. Hypothermia is a real threat. Adequate warm clothing and proper gear is a must. Don't forget sunscreen! The warming hut is a welcome bonus at Hidden Valley offering a heated indoor place to take time for rest; bring drinks and food to keep hydrated and energized. Even in winter months, there are opportunities for bird and wildlife viewing. Stellar’s jays, Clark's nutcrackers, gray jays, ravens, chickadees, woodpeckers, and turkeys are often seen throughout this valley. Moose, elk, and deer enjoy browsing along the willows that poke above the snow. Be watchful for coyotes looking for prey. All sorts of fun can be had at Hidden Valley in the chill of winter. So, layer on your warm clothes, choose your gear, and come play in the snow at Hidden Valley.  Marlene has been photographing Colorado's wildflowers while on her hiking and climbing adventures since 1974. Marlene has climbed Colorado's 54 14ers and the 126 USGS named peaks in Rocky. She is the author of Rocky Mountain Wildflowers, 2nd Ed, The Best Front Range Wildflower Hikes, and Rocky Mountain Alpine Flowers, available for purchase here. The publication of this piece of independent and local journalism was made possible by the Bank of Estes Park and Longhorn Liquor.

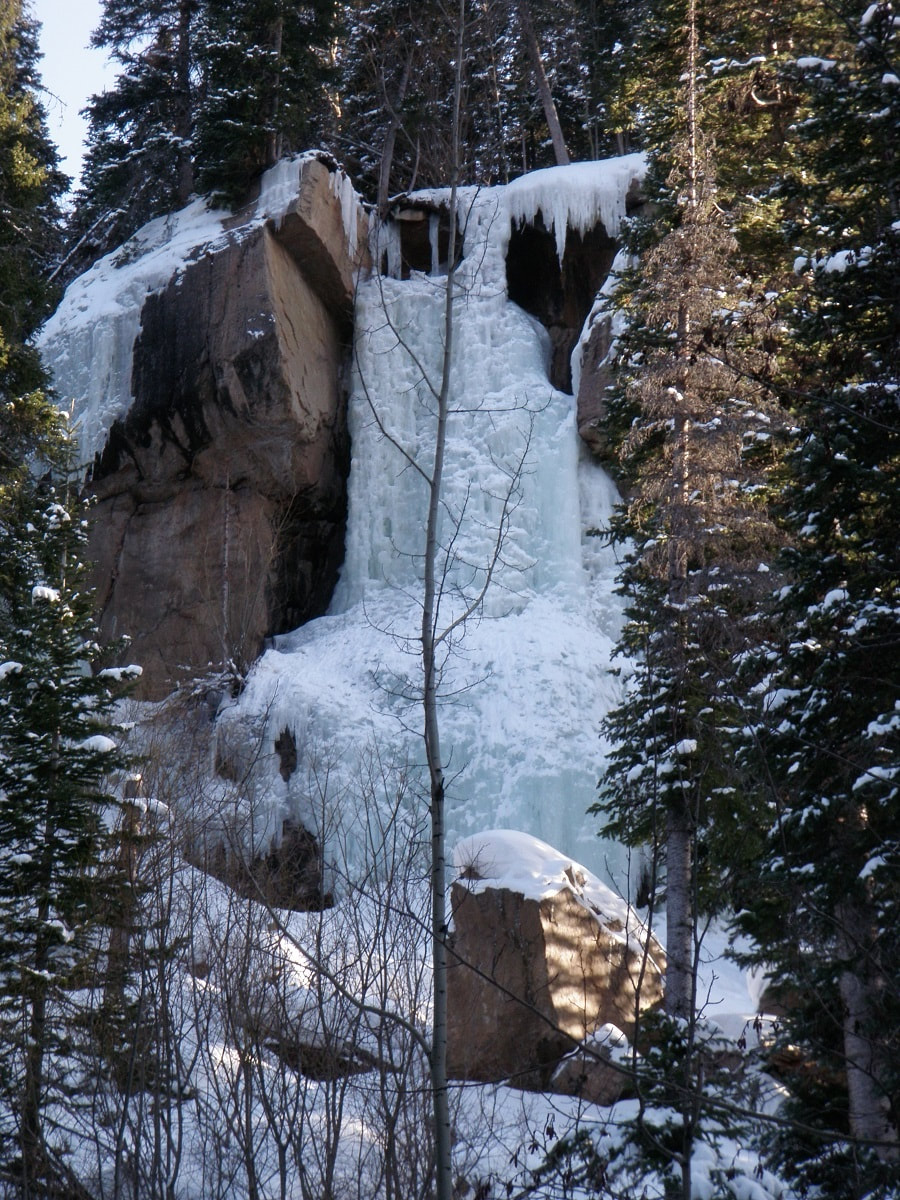

story and photos by Rebecca Detterline The golden peach light hitting the December snow on these shortest days of the year always brings me to a place of quiet contemplation. Pausing at the Saint Vain bridge 2.4 miles from the Wild Basin winter parking area, I breathe in the cold winter air and reflect on the past decade. When I moved to Allenspark in 2012, Wild Basin quickly became my sanctuary. Whether fly fishing in Ouzel Creek, tagging a remote summit or jogging up the Finch Lake trail, I always feel at home in The Basin. During the winter season, the far reaches of Wild Basin are inaccessible to most of us mortals, buried deep under an untouched blanket of snow. Skiing off the summit of Mount Copeland in January of 2017 required starting in the pre-dawn darkness and ‘over-skiing my headlamp’ on a dark, icy trail well after sunset. I almost made it to Thunder Lake on skis in early 2020, but breaking trail in deep snow, route-finding difficulties, and the impending sunset forced my partner and I to turn around just 1/2 mile shy of the lake. The Wild Basin winter parking area will sometimes fill up on busy winter weekends, but spots can usually be found in the nearby summer stock parking loop. Weekdays, however, offer much solitude. Hikers can plan to share the one-mile stretch of road between the parking area and the Wild Basin trailhead with a handful of ice climbers, cross-country skiers, and families trying out rental snowshoes. The road is usually hard packed, as is the short trail that leads to Hidden Falls. However, hikers should carry snowshoes and anticipate breaking trail for destinations along the Wild Basin Trail. In the summer months, Hidden Falls is nothing more than a trickle of water seeping out of an overhanging rock ,100 feet above the forest floor. In the winter, that trickle transforms into a spectacular frozen waterfall, very popular among ice climbers. The round trip distance for this hike is approximately 3.5 miles. From the parking area, follow the road past the Finch Lake trailhead. Just before the road takes a sharp right and crosses the North Saint Vrain Creek, look for a sign for a horse trail and follow the hard-packed trail to Copeland Falls. Continue along the trail, looking to the south for glimpses of this impressive ice column. The climbers’ trail heads up to the left and is generally easy to spot. This trail steepens and continues to the base of the falls, but quickly becomes covered in solid ice. Crampons are needed for this section of trail and hikers should enjoy the views of Hidden Falls from below this icy slope, safely out of the way of any falling ice chunks the climbers might dislodge. Ouzel Falls is a worthy destination in any month of the year, but the most solitude is found on the shortest days. But hikers need not travel 3.7 miles from the winter parking area to enjoy the quietude of Wild Basin in the wintertime. Only .3 miles from the Wild Basin trailhead, winter hikers can revel in the rare opportunity to have Copeland Falls all to themselves. Pausing at the bridge that crosses the North Saint Vrain Creek 2.4 miles into the hike, I watch the water flow between the rock slabs and ice sheets that encase them. So much literal and proverbial water has flowed under this bridge in the years since I’ve made this place my refuge. Through triumphs and heartbreaks, fires and floods, anguish and joy, the trails in Wild Basin have been an enduring comfort. The seasons of life are not so predictable as the seasons of the year, but the ever- flowing snowmelt in the creeks and waterfalls of this magical place always brings a sense of peace. Whether hiking to Hidden Falls, Copeland Falls, Calypso Cascades, Ouzel Falls or destinations beyond, the tranquil solitude of a winter visit to Wild Basin is sure to leave the hiker feeling refreshed and rejuvenated. The darkest days are behind us now and Wild Basin is an ideal spot for quiet reflection as we begin heading for light.  Rebecca Detterline is a lover all things RMNP. She is a wildflower aficionado whose favorite hiking destinations are alpine lakes and waterfalls. Her name can be found in remote summit registers in Wild Basin and beyond. Originally from Minnesota, she has lived in Allenspark since 2011. The publication of this piece was made possible by the Mad Moose, and the Country Market, both of Estes Park.

Story and photos by Marlene Borneman While winter officially begins with the Winter Solstice, Rocky Mountain National Park can dish out harsh winter conditions as early as October! Being out in the winter months over the years has taught me to prepare for the unexpected. Frostbite and hypothermia are real risks when traveling in the Colorado backcountry this time of year. Hikers should be sure to check the forecast before heading out. I carry spikes, snowshoes, and layers of clothing to be sure I am ready for the ever- changing conditions. I have come to appreciate Rocky in chilly, snowy and yes, even windy conditions. The landscape is transformed to a peaceful, awe-inspiring, and captivating space to recreate or just to pause. Snow glistens like scattered glitter and icy streams create fine art. The seed pods of common plants are a challenge to identify in their winter form. Lucky hikers may spot a snowshoe hare, ptarmigan or ermine in white winter camouflage. Winter offers so much to observe, learn, and wonder about. Flattop Mountain and Estes Cone have been two of my favorite winter hiking destinations for many years. These trips can range from relatively straightforward to very challenging, depending on weather and trail conditions. Flattop Mountain has given me the extremes. The summit is 12,324 feet in elevation and the starting point at Bear Lake is 9,450 feet. In those 2,894 feet of elevation difference, both the weather and trail conditions can rapidly change in winter. A 2021 winter day started out cold, but not bitter. As I climbed higher the winds became stronger, temperatures dropped to the 20s (not including the wind chill factor) and enough snow covered the trail to require the use of snowshoes.  On a windy, winter day in 2021, the author encountered a covey of white-tailed ptarmigan in their winter plumage. On a windy, winter day in 2021, the author encountered a covey of white-tailed ptarmigan in their winter plumage. Due to the wicked winds up above 12,000 feet, I turned around. But the day was not a loss. On the descent I heard a faint cackling sound which I quickly recognized as a ptarmigan call. Rocky is home to white-tailed ptarmigans which live in the alpine during summer months and go down the to sub-alpine levels in winter, where they can feed on willows at the edges of snowfields. It took me a minute searching the landscape to spot a tiny dark spot in the snow, the eye of a ptarmigan. Soon I saw not one, but about a dozen ptarmigans huddled together sharing their warmth in a snowbank. This sighting made me forget the wind and cold at least momentarily. In contrast, January 5, 2018, was windless and sunny, with mild temperatures and little snow on the trail, requiring only micro-spikes. It was a very pleasant day to be on Flattop. The American Pika was scurrying between the boulders, possibly trying to soak up the “warmth” of this winter day. Pikas do not hibernate as marmots do, but it is still unusual to see them in the dead of winter frolicking around. They often stay near their “haypile” hidden under rocks as most of the plants are buried in snow. On other winter trips on Flattop trail I have caught sightings of dusty grouse and, lower on the trail, turkeys. Estes Cone stands at 11,006 feet, not quite above treeline. Starting at the Longs Peak Trailhead at 9,400 feet, there is often enough snow to wear snowshoes from the start but if not, I carry a pair because up higher, they may come in handy. Soon I reach the junction for Eugenia Mine which is an abandoned gold mine from the early 1900s. Now all that remains are a few timbers from cabins, rusty pots, and tools which are now buried under winter snow. The wide meadow ahead is called Moore Park and is often wind-scoured, resulting in an icy trail. A few winters ago, I spotted a snowshoe hare in winter white along this section. A second junction marks the way to Storm Pass. It is only .7 mile to the summit from Storm Pass; however, the trail becomes gnarly from here. Hikers can anticipate steep, rocky terrain through a tangle of forest. Sometimes I have been able to keep snowshoes on if the snow cover is good, otherwise spikes are the best tool to climb up this arduous section. Below the summit a steep gully, often filled with ice and snow, awaits the hiker, making it a tricky climb to the top. The route flattens out before climbing up to a hefty rock outcropping where the summit rests. Winter months often bring high winds to the top of Estes Cone making the summit stop brief. Despite the wind and cold the summit offers tremendous views in every direction. To the east lay Twin Sisters Peaks, Lily Lake and Lake Estes. Longs Peak Massif rises to the west along with the peaks of the continental divide. The Mummy Range dominates the view to the north. This impressive panoramic view makes every frosty step toward this accomplishment worthwhile. On December 11, 2022, I attempted Estes Cone on a day when high winds caused the snow to form deep layers of crusty snow. Snowshoes were more of a hindrance than a support. The crust would break through in slabs causing the snowshoe to sink. I only made it to Storm Pass that day. In those snow conditions my day was done. I sat a long time at Storm Pass in the still cold, crisp air just taking in this vast wilderness. Not a bad day at all.  Marlene has been photographing Colorado's wildflowers while on her hiking and climbing adventures since 1974. Marlene has climbed Colorado's 54 14ers and the 126 USGS named peaks in Rocky. She is the author of Rocky Mountain Wildflowers 2nd Ed, The Best Front Range Wildflower Hikes, and Rocky Mountain Alpine Flowers. This week's free story is brought to you by Snowy Peaks Winery and Xplorer Maps.

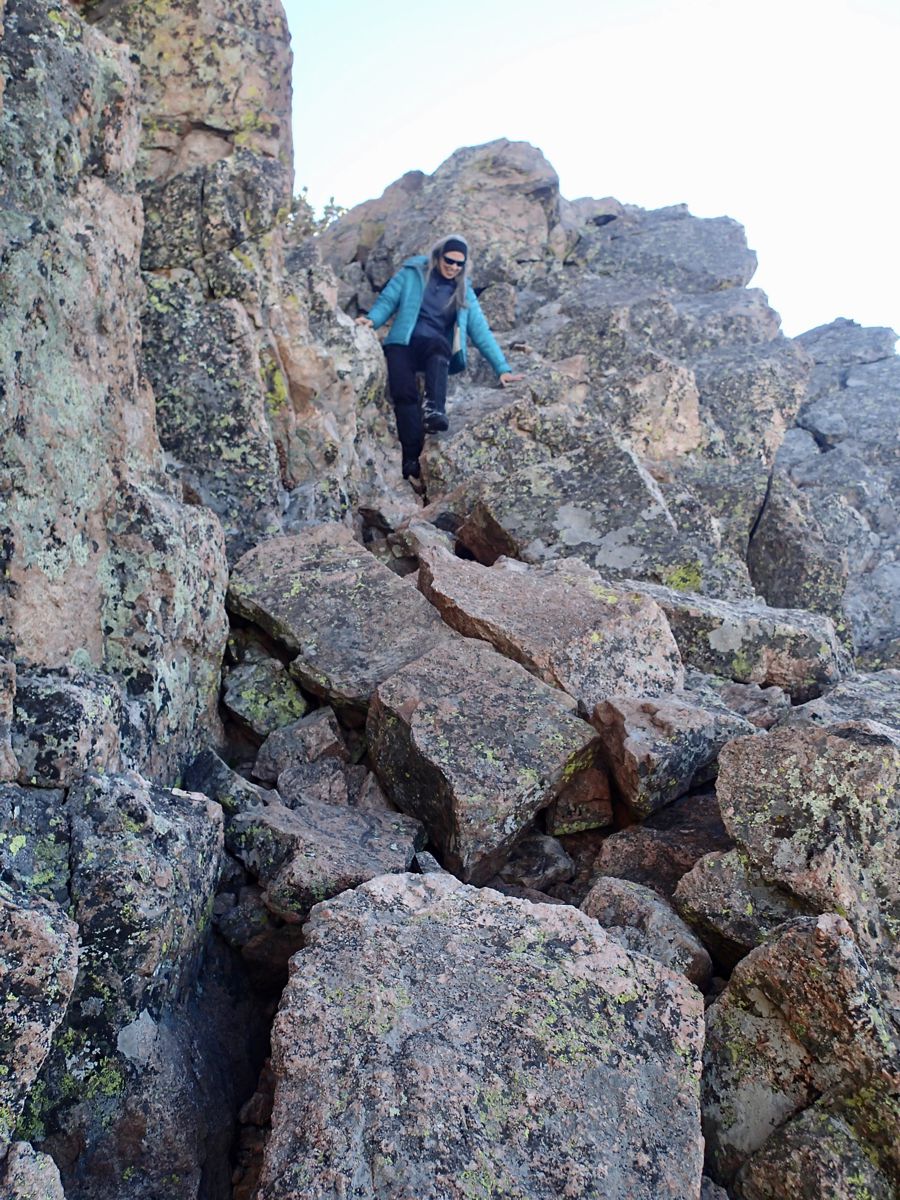

This article is extracted from the current issue of HIKE ROCKY magazine; to learn more about becoming a member to read the entire publication, click here Story and photos in all seasons by Marlene Borneman Lake of the Clouds Mileage: 14 miles round trip, in and out Elevation gain: 2,390 feet Class 2: Use of navigation skills, may use hands for balance on steep talus slopes/boulders Rated: Difficult Lake of the Clouds sits at 11,430 feet among the “cloud” peaks named after cloud formations. Mount Cirrus and Mount Howard loom above the lake with Mount Cumulus and Stratus to the south. It is the largest lake west of the Continental Divide in the Never Summer Range. This section of the park is remote, rugged, encompassing stunning alpine scenery. Before mid-July be prepared to hike on snow including steep snowfields which may require special gear and experience on snowfields. This adventuresome hike starts at the Colorado River trailhead. The trail sets off steeply but soon levels off into quiet forest and meadows. Wildlife is often seen near the river so be watchful for elk, moose, and deer. The trail continues up switchbacks for 3.5 miles until the Grand Ditch Road is reached. The Grand Ditch is a 15-mile canal built over a hundred years ago to divert water (run off) from the Never Summer mountains to the east side of the Continental Divide. The water would otherwise go into the Colorado River. This diversion is a water source for the Front Range and beyond to the eastern plains. The Colorado River was formerly called the “Grand” River where the name Grand Ditch was derived. Work on the ditch began in 1894 and was finished in 1934. It is easy walking on the ditch road giving time to soak up the views. A variety of wildflowers grow along the “ditch” and in late summer, ripe tasty raspberries. Follow the Grand Ditch Road for 1.8 miles to Hitchens Gulch crossing a foot bridge. Here Big Dutch Creek cascades into the Grand Ditch. Now, the adventure really begins. Follow the trail to the backcountry campsite Dutchtown. Dutchtown was a mining camp named after German (Dutchmen) prospectors abandoned in 1884. Along the way several lush meadows line the trail filled with alpine laurel, marsh marigolds and globeflowers. Gortex boots come in handy hiking in these wet and often very muddy meadows. In early summer avalanche lilies are a treat to find along this section. In late June throughout most of the summer rose crown, Indian paintbrush, star gentians and many more wildflowers color the landscape. Leaving Dutchtown campsite the trail becomes faint. Stay on the north side of the creek following cairns to reach a large boulder/talus field. This boulder/talus slope is immense and feels overwhelming. A sizeable“bowl” sits above this steep slope which holds Lake of the Clouds. An impressive waterfall flows from the lake down the boulders below forming Big Dutch Creek. Looking north are dramatic views of Lead Mountain. On the boulder/talus slope there are many cairns going in every direction. No matter which route taken, stay on the north side (right hand side) of the waterfall scrambling up large boulders. Assume every boulder will move when stepped on, so balance is key. Grassy ledges above the boulders offer a route on somewhat easier terrain. Topping out on tundra, it is an easy walk to the lake. Lake of the Clouds offers sweeping views. The lake is surrounded by alpine flowers; Old Man of the Mountain, columbines, dotted saxifrage, moss campion, sky pilot, alpine avens just to name a few. Whistles of yellow-bellied marmots and squeaks of pikas may also be part of the scene. Marmots are the largest member of the squirrel family. Marmots are very curious animals. Walking away from a daypack is just an invitation for a marmot to tear into it in search of food. Marmots hibernate in the winter so summer months they are occupied gaining body fat. Pikas are hard- working small furry mammals in the rabbit family. Pikas do not hibernate. They scurry rapidly across the tundra gathering plants to store for their winter food stash. Follow the route back to the Grand Ditch Road down to the Colorado River trailhead. Some may say this is a really demanding hike, but the rewards of the day are worth every step.  Marlene has been photographing Colorado's wildflowers while on her hiking and climbing adventures since 1974. Marlene has climbed Colorado's 54 14ers and the 126 USGS named peaks in Rocky. She is the author of Rocky Mountain Wildflowers 2nd Ed, The Best Front Range Wildflower Hikes, and Rocky Mountain Alpine Flowers. This story of local and independent journalism was made possible by: Castle Mountain Lodge and Rock Creek Tavern.

Story and photos by Chris Reveley for HIKE ROCKY magazine Editor’s note: The Tonahutu Trail was reopened on July 9, but closed again on July 21. This hike was taken on July 13, 2022. October 14, 2020: The East Troublesome Creek Fire was first reported, burning in the hills, northeast of Kremmling, Colorado. Pushed eastward by high winds, the blaze would leave two people dead and consume hundreds of structures in its path. Entering the National Park, the fire quickly burned halfway up the North Inlet valley and through the entire Tonahutu Creek drainage. Reaching tree line and lacking fuel, the fire's aerial acrobatics allowed it to vault over more than a mile of dry, grassy tundra to re-establish itself east of the Continental Divide. High winds continued and Estes Park was evacuated. The flames marched to within two miles of the town's west boundary. The Tonahutu trail starts near the summit of Flattop Mt. and travels northwest across the tundra before descending toward Grand Lake, passing through some the worst of the Park's fire damage. It had been closed to hikers and backcountry campers since the fire; blocked by many fallen trees and threatened by the still-standing, blackened skeletons of others, the trail was unsafe and impassable. Bridges, signs and hitching rails were destroyed. In July, after almost two years of restoration and rebuilding by determined RMNP trail crews, the Tonahutu trail was reopened to the public. I wanted to see it for myself. The shortest hiking route from the Park's east side to the west is about 15.5 miles and starts at Bear Lake with 4.4 miles up steep, rocky terrain on the Flattop Trail. With a reliable headlamp (and a backup!) I always do the first few miles in the dark, timing my arrival at tree line with the sunrise. Over the last 50 years I've taken scores of photos from this area; sun peeking up over the plains, the monolith of Longs Peak brooding to the south, first light touching the Mummy Range. These views never look exactly the same twice so here I am, taking all the same pictures again! Funny. Just past the Flattop summit there's a choice to make; left on the North Inlet trail or right on the Tonahutu. Both trails wander across tundra for a distance, marked by large rock cairns built up by passers-by over many years. Before long, the Tonahutu begins to descend into the valley it will follow to Grand Lake. As I drop down off the treeless tundra, stunning views down the charred valley are revealed. Suddenly, I arrive at the exact place where the fire became air-born and crossed the tundra to reach the Park's east side. This is what I came to see. All the trees are burned, right up to the point where the trail drops into the former forest. But then, something strange: There are a few small groves of big trees above this spot that somehow survived, sandwiched between the complete destruction that came roaring up the valley and the tundra. What would I have seen, standing to the side as the fire passed? Did the steepening slope and the rising winds cause the firestorm to ascend vertically, going totally atmospheric and missing a few lucky survivors? The next six miles of trail pass through one long graveyard of blackened coniferous hulks, sculpted by flame. Many have been burned almost completely through, leaving me wondering what is keeping them upright? With the first strong wind the trail will likely be covered by burn debris again. Scores of the fallen trees that had blocked the path have been cleanly sawed through and removed by trail crew teams. By the time I reach the Green Mt. trail junction and finish the last couple miles to the parking lot, I've counted at least five newly-constructed bridges, lots of new trail signs and several rebuilt trail segments. I've met Paul, a Park Service employee who is far up the valley, alone, hiking with a large pack. He is surveying backcountry assets, particularly important in the aftermath of the fire. I've stopped to thank the ladies and gentlemen of a trail crew. They look tired. There is nothing particularly glamorous about this work but what they've accomplished is impressive. “We have a lot more to do”, they admit. By the time I arrive at the Green Mt. trailhead, I've taken 70 photos. The blackened forest climbs thousands of feet up the sides of the valley while lush, green undergrowth has returned and covers the low, wet areas. The contrast is startling but hard to capture with my phone's camera. And the damage goes deeper: A Park Service naturalist tells me the fire's extreme high temperatures have sterilized the soil in many places, making any kind of new growth impossible for a long time. Normally, along this traverse of the Park, I would see bighorn sheep, moose, elk and deer. Today, no wildlife at all. Investigations have concluded that the East Troublesome Creek Fire was started by people, not lightning. Was it intentional or accidental? Could those responsible have imagined what the results might be when they started the fire? Here in the bone-dry West, it is probably time to abandon the tradition of a roaring campfire during the dry seasons. Wise management of our natural resources includes education and planning as well as acknowledging our ability to do great harm, accidently or otherwise. How should we respond to those whose neglect or intentional actions damage these fragile terrestrial and atmospheric shells we inhabit? As the species with the greatest intelligence and the greatest negative impact we bear the greatest responsibility. But, again and again, we are failing the Good Stewardship Test. Our relationship with the earth is both loving and abusive, trending more toward the latter as our benign inattention allows environmental disasters to proliferate. It may be that humankind lacks the intelligence, foresight and desire to maintain the planet, happily trading short-term profits for long term survival. If we can't stop poisoning our home, our relatively brief 70-million-year residence on planet Earth will come to a whimpering end, only to be appreciated by other, surviving life forms as a cosmic, not-to-be-repeated experiment in neglect and exploitation. The evidence is in: forest, water and atmosphere are not unlimited resources that will rejuvenate and regenerate faster than we are destroying them. Sadly, environmentalism has become a political issue with a portion of our population denying there's a problem. We elect “leaders” to make wise decisions and, more and more, they are willfully and proudly ignorant, incapable of understanding the issues, much less responding wisely. Again, today, after thousands of adventures of all kinds in RMNP, my passion for the place survives, undiminished. The future of the Park and, indeed, the planet can be bright. It's entirely up to us.  Chris Reveley has spent 50 years climbing and doing endurance sports; and, thirty years learning and practicing medicine. “Now I’m a Happy House Husband with hobbies,” he said. The publication of this piece of independent and local journalism was made possible by Erik Stensland's Images of RMNP and The Country Market, both of Estes Park.

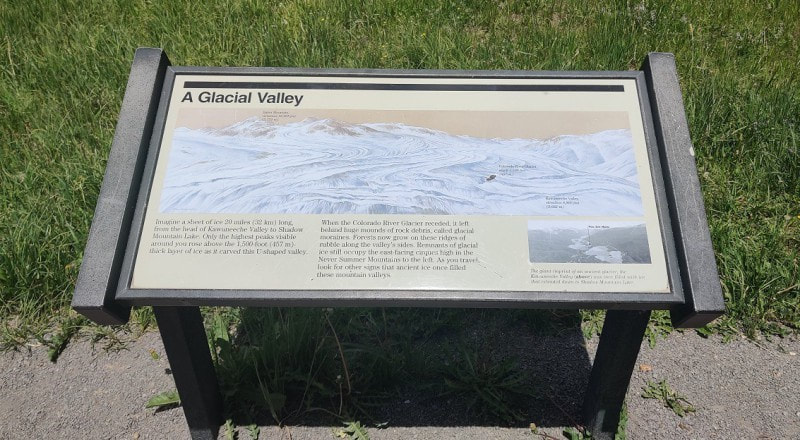

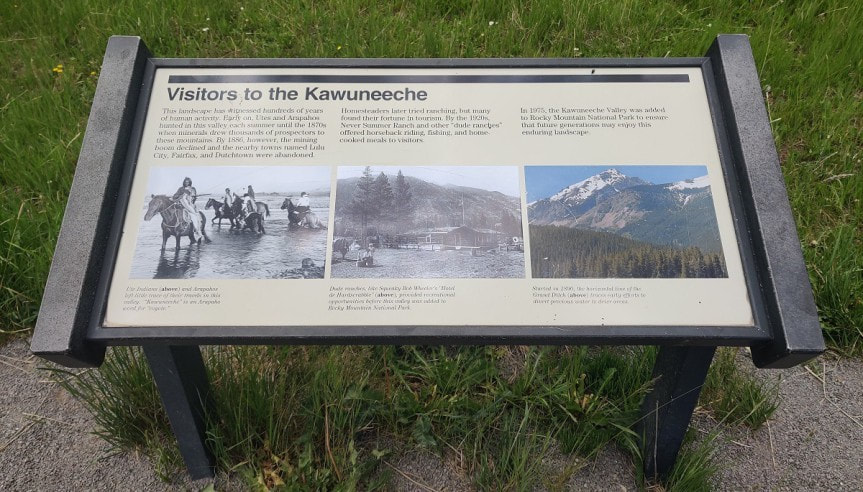

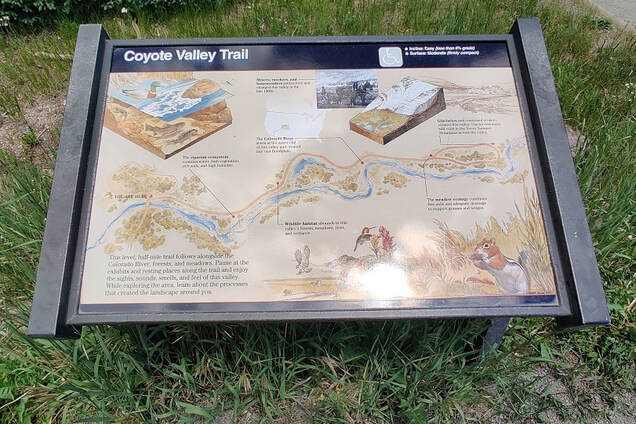

Deep history and geology in the Kawuneeche Valley Story, video, and photos by Barb Boyer Buck Video edited by Quinton Rusk The Coyote Valley Trail, located on the west side of Rocky Mountain National Park, is a half-mile stroll through the Kawuneeche Valley. Situated between the Front Range and the Never Summer Mountains, carved by glacial movements and the headwaters of the Colorado River, this mile-wide valley is beautiful and home to a plethora of wildlife. Two years ago, the East troublesome Fire burned into the southern part of this valley to create devastating damage extending into the town of Grand Lake. But where this trail begins, in the northern section of the valley, the land was spared. This is one of several handicapped-accessible, interpretive nature walks in Rocky that immerse the visitor in a comprehensive science and history lesson. It also offers many spots to rest, great access to the Colorado River for some catch-and-release flyfishing, and wonderful wildlife viewing. Signs along the way educate the visitor about the history and ecology along headwaters of the Colorado.  To truly understand this valley, we need to go back tens of millions of years ago. Through the violent creation of the mountains surrounding the Kawuneeche (Arapaho for “Coyote Creek”) Valley, there are outcroppings of rock that date back nearly two billion years – formed before the evolution of multi-cellular life. Rocky Mountain National Park now preserves some of the most expansive mountainous terrain in the country but this land once was covered in a vast sea, for the most part. The formation of the Front Range which is adjacent to the valley on the east side, started with what geologists call the “Laramide Orogeny or Revolution." “Near the end of the Cretaceous Period… poorly understood forces began to propel the range upward…” wrote historian Thomas G. Andrews in his book, Coyote Valley: Deep History in the High Rockies (2015). “By the time the earth ceased its squeezing and thrusting about 45 million years ago, the former low-lying heart of North America had risen some three miles above sea level.” Next came the formation of the Never Summer Mountains. Volcanic eruptions approximately 27 million years ago created these mountains that border the west side of Kawuneeche Valley and the southwest edge of Rocky Mountain National Park. These mountains were once up to 17,000 feet in elevation before erosion whittled them down. Nestled between these two ranges is the subject at hand: a low- lying area where the forces of water and ice carved out a nearly 20-mile long valley, running north-south. The first traces of human activity in this valley are from approximately 13,000 years ago, but its use diminished and by 11,000 years ago, when the ice age made another severe grip on the area, humans had moved on to warmer climates. Slowly, the weather improved and people returned to the valley to hunt and gather in the summer months. This magical valley, created by the forces of adjacent mountain-building events and continuous glacial reduction had been utilized and managed by these humans for ten thousand years before the arrival of any other people. North American native populations were displaced from their homelands beginning in the 16th century with the arrival of the Spanish, pushing indigenous nations further west over the next three centuries. But the northern part of the Rockies remained too remote for Spanish colonization, and the adaptive nature of the Nuche (ancestors of the Ute Nation) allowed them to thrive in their nomadic territories, especially after the arrival of the horse. Eventually, the displaced Arapaho nation utilized these hunting grounds, too, and fierce battles were held between the two nations in the Kawuneeche Valley. European colonists appeared with the fur traders, then those seeking silver and gold, and finally, settlers. By the late 1800s, the Nuche were displaced permanently and thus, their nomadic mountain tradition came to an abrupt end. Settlers arrived in the late 1800s to “try their hand at ranching,” but most of these homesteads were eventually turned into guest ranches. The Kawuneeche Valley was added to Rocky Mountain National Park in 1975. Now, let's turn our attention to the headwaters of the Colorado River which cuts through the Kawuneeche Valley and travels on to Mexico, 1,450 miles long. It passes through 11 National Parks and is the sixth longest river in the nation. This waterway created the Grand Canyon and is used for water supply in several drought- prone cities such as Las Vegas, Los Angeles, Phoenix, and Houston. Today, the river runs at critically low volumes in these watersheds. “Water stored in the Colorado River's biggest reservoirs has declined during the past two decades due to climate change and overuse. The river and its tributaries provide drinking water to 40 million people, and irrigate millions of acres of cropland. In addition to the seven U.S. states, the river also crosses into Mexico and provides water supplies to cities and farmers in two Mexican states as well.” (from “7 states and federal government lack direction on cutbacks from the Colorado River,” by Luke Runyon for NPR, published August 27, 2022). The article goes on to state this shortage has been linked to decades of poor water management along the reservoir routes and may lead to the eventual elimination of recreational and irrigation uses of the Colorado River. But along its headwaters, it is running clear and fast – even in late summer, due to the above-average precipitation experienced in Rocky Mountain National When you stroll along the Coyote Valley Trail, the riparian habitat is thriving and hosts a plethora of wildlife such as moose, beaver, and muskrat while numerous species of trout swing in the river. Deer, moose, and elk stop by for a drink, insects buzz (remember your bug spray!), and frogs sing. It’s the perfect place to learn something new!  Barb Boyer Buck is the managing editor of HIKE ROCKY magazine. She is a professional journalist, photographer, editor and playwright. In 2014 and 2015, she wrote and directed two original plays about Estes Park and Rocky Mountain National Park, to honor the Park’s 100th anniversary. Barb lives in Estes Park with her cat, Percy. This piece of local and independent journalism was made possible by Backbone Adventures and Kirk's Mountain Adventures, both of Estes Park.

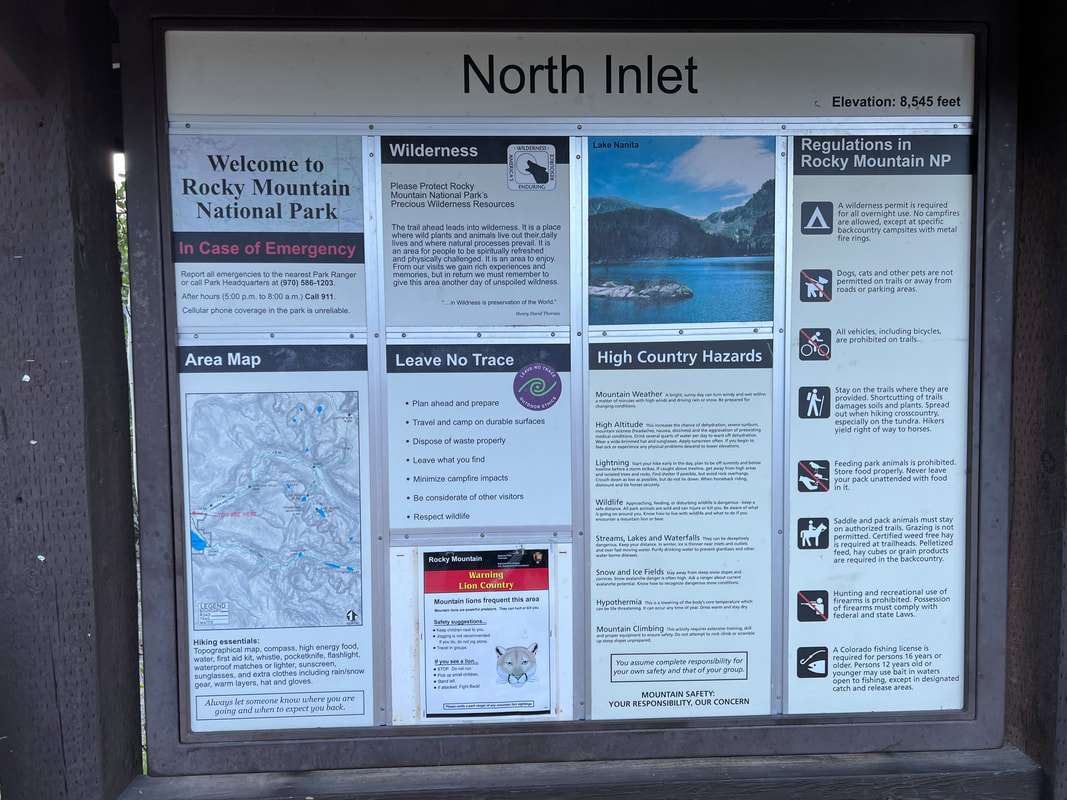

Story and photos by Jason Miller Cascade Falls Trail Location: North Inlet Trailhead Roundtrip Length: 6.8 Miles Trailhead Elevation: 8,510 Feet Total Elevation Gain: 430 Feet Highest Elevation: 8,811Feet Trail Difficulty: Moderate When I was asked to do Cascade Falls for a late-June hike, I was excited to say the least. The last time I had seen the falls was six years ago. My wife and had I hiked from Bear Lake Trailhead up and over Flattop Mountain then down into Grand Lake: 17.5 Miles and 3,050 ft elevation gain. We had camped overnight and had a wild bear experience. This turned out to be a “Grand” adventure of its own, but that story is for another day. We had been so exhausted by the time we went by Cascade Falls that we didn't take the time to enjoy these awesome falls. This time, I am going to enjoy it! In order to beat the crowds, I left my house in Glen Haven at 4:20 a.m. This hike starts at the North Inlet Trailhead located in Grand Lake, CO. It's 48 miles from Estes Park to Grand Lake, but you are lucky enough to traverse Trail Ridge Road. This road was built in 1931 and gets to an elevation of 12,183 ft above sea level. The views of Rocky Mountain National Park are spectacular. It is a beautiful, clear morning with a temperature of 34 degrees at the Alpine Visitor Center. After driving down the mountain towards Grand Lake for a few miles, I was fortunate enough to see five moose and multiple elk alongside the road. I was a little surprised when arriving at the North Inlet Trail: the road access to the trailhead parking was washed out from a previous rain. This added an extra one-mile walk with slightly more of an incline than one likes to endure. Getting to the trailhead sign was a joy because the land ahead looked flatter. Through the large valley littered with pine trees I could see no one. Yes! Not a soul in sight. This hike begins with a very gentle uphill slope for the first mile or so along an old, dirt service road. You will cross private land all along this section of the trail. Please stay on the designated route. The trail eventually narrows into a single-track trail through the burnt conifers and along rocky cliffs. There are remnants of the fire everywhere to be seen: thousands of acres burnt to a crisp and large standing trees with the scars of previous fire battles are all around. The smell is horrifying. The sun glare was so intense that I kept my hat down over my eyes with sunglasses on, looking down at my feet. Please don't do this. I walked right past 3 moose. This could have been tragic. I noticed a couple more moose up ahead and continued walking slowly while trying to capture this epic event. I was able to snap a couple good pictures and a video. Traversing a little farther up the trail turned out to be more of the same. More moose and thousands of beautiful wildflowers peppered the landscape. Now we are getting to the point of the hike that takes a turn. No, not a bad turn. It just gets a little tougher. There is a slight incline for the remainder of the hike to Cascade Falls. Be prepared for an increase in heart rate. As I climbed deeper into the forest, the sounds of the river were growing louder. Was I getting closer to the river? It's getting bigger. I am at the falls! Arriving at Cascade Falls was amazing. The sound coming from the rushing water was lovely and overwhelming at the same time. I scrambled down to the lower falls and snapped a few pics. Next, I climbed back up to the trail to get to the upper falls. The vantage point from here is crazy. I love Rocky Mountain National Park. This seemed like a great spot to rest and have something to eat and drink. I am over 4 miles into this day of hiking and have yet to see any other people. It’s so peaceful. I re-energized and got on my way back. Going downhill tends to be where most of the sprained ankles happen, so go slow and steady when descending. As I was walking back through the charred forest, the smell seemed like it was burning through my nose every step of the way. Through the fire will come lots of new growth. The wildflowers and lush green grass are coming back already. Pine trees take an average of five to ten years to rejuvenate. I will put this hike on my list of "Must Do Every Year" hikes. The changes in the years to come will be nature inspiring. Rocky Mountain National Park has a reservation system again this year. If you do not have a reservation to come through the gates after 9:00 a.m. you will be turned away. “Insider Hack” – Get through the gates before 9 a.m. Take your time hiking and spend the day in Grand Lake. Go back through the gates after 3pm. No reservation needed that way.  Remember to stop and smell the wild roses! Remember to stop and smell the wild roses! I love hiking early so I can avoid the crowds and have a better chance to see wildlife. By the time I made it back to my truck it was 9:45 a.m. I had seen at least 15 elk, 12 moose, and 6 people. Not bad in my eyes. Overall, this hike is relatively easy, but the difficulty lies in the distance. The roundtrip is over 7 miles from the actual trailhead. Get outside and go see this magnificent water feature! PRO TIPS

- If ya can't beat 'em ... join 'em: recreation.gov for reservations  Jason Miller, 49, is a resident of Glen Haven and is married with two children. Before moving to the area, he used to work as broker for Nestle USA and H.P. Hood milk company. Today, he is the co-owner of Lightbrush Productions, LLC The publication of this piece of local and independent journalism was made possible by Images of RMNP and Snowy Peaks Winery, both located in Estes Park.

The wild requires that we learn the terrain, nod to all the plants and animals and birds, ford the streams and cross the ridges, and tell a good story when we get back home. - Gary Snyder Story, photos, and video by Dave Rusk Ahh yes, my idea of a good day in the mountains! Although, sometimes a good day in the mountains does not always lend itself to a good story. “No, we didn't get lost. Yes, we made it to our destination. It was sunny all day.” If all goes well, it can be a challenge to tell a good tale by simply sharing the joy one experiences of being in the mountains. “Yes, it was a terrific day!” And often, it's left at that. My hiking partner, Jonathan, put it in a different way, “Bad decisions make good stories.” Now, I'm not recommending that anyone go into the mountains with the intention of making bad decisions just so they can have a good yarn to spin at the end of the day. No one would want to slip off a log crossing and splash about in a stream so cold it takes your breath away and then shiver in wet clothes the rest of the day, or cower under flashes of lighting and sonorous thunder so overwhelming you feel certain the surrounding mountains will crash down upon you at any moment, all the while wondering if you will make it out with your life. But they do make good stories at the end of the day. No, when I go into the mountains, I try to avoid bad decisions. But I wondered, as Jonathan and I headed out for an early season hike up Flattop Mtn., what the possibilities were of us making a bad decision on that particular day. Would I have a tall tale to tell upon our return? Only time would tell. Normally when I hike the Flattop Mtn. trail, I'll go sometime in July when I know the trail is mostly free of snow and the alpine flowers are putting on a grand show. But I promised my editor a story on hiking Flattop, and possibly Hallett, and while I have done this hike many times over the years, I've never hiked it in early June. I do remember the first time I hiked this trail. It was a warmish July day, perhaps 80 degrees in Estes, and I was huffing my way up above the treeline, hiking in shorts and a t-shirt and feeling the warmth of the sun at these high elevations. Sweat had started to soak into my t-shirt under my day pack. But I kept noticing all these hikers that were coming down bundled up in jackets and warm hats, some even with gloves on. Odd, I thought. But once I got to the top, it made sense. Soon after I sat down to rest and have a snack, a cool alpine breeze began evaporating my sweat and I felt chilled. I was glad I hauled up extra layers of clothes in my day pack. One summer as I was hopping my way down the trail, I came across a friend from Boulder who was running up the trail. He's a head taller than everyone else with thick wavy blond hair and I recognized him right off as he side-stepped by people, keeping up a pretty steady uphill pace. As he approached I said hi and his momentum that was pushing him up the 2,874 feet of elevation gain at 11,000 ft, brought him to a halt. We talked briefly, but I realized he was in training for the Leadville 100; he's a mountain runner, and I didn't keep him long. He pushed on, regaining his momentum and leaving me to wonder how he could run up the mountain like that. On another day I was heading up, not yet breaking out above treeline, and I passed another friend (Michelle) who was already heading down and only a few miles from finishing the nearly 9 mile round trip hike. I realized, as we said our goodbyes, that she may have started early enough to watch the sun rise from the top. On many of my hikes up the Flattop trail, I encountered enumerable marmots with their bodies spread flat, soaking up the summer sun and pikas calling their high-pitched warning while in their never- ending pursuit of gathering nesting material. But mostly I remember the alpine wildflowers: moss campion, alpine bluebells, the old man of the mountain sunflowers (with the wings of checkerspot butterfly spread wide in the morning sun.) My favorite is the the deep rich blue of the Sky Pilot with its golden yellow anthers dotting the center, mixed together with golden yellow alpine avens. But this was the earliest I have ever hiked up Flattop and with all the very late May snow fall (a winter weather advisory had even been issued on the last day of May), I wondered if going was the best decision, or was I just asking for a story? Having obtained a last-minute early morning reservation the night before, we were able to get to the Bear Lake parking lot at a leisurely 7 am. We strapped snowshoes on our packs not knowing what the snow conditions might be like. Around Bear Lake, the trail started off snow-free, but then became snow covered before we got to the Flattop Mountain cutoff. The snow trail remained packed but was slippery, and after a short time we stopped to put on our shoe spikes to improve our upward traction. After visiting with some hikers already on the way down, we determined that the snow conditions would remain firm enough and enough. We found a tree well to ditch the snow shoes; we just had to remember where that spot was on the way back down! Would this be a bad decision? Most of the pack snow trail was easy to follow, but we also used a GPS tracking device (like GPSMyHike) to ensure we didn't lose the summer trail hidden below the snow. We steadily made our way up crossing through treeline. But once onto the open alpine, we were greeted by a stiff wind and we put on our wind jackets. The wind was not a biting cold and my bare hands, gripping poles to keep me steady, never got too cold. At one point, we stopped for a breather at a bare patch of tundra and I saw movement on the ground. There, not more than 10 feet from us were a pair of ptarmigan, their plumage transitioning from a winter white to a mottled summer brown, but blending perfectly with the transitioning tundra. Believing themselves invisible, they slowly strutted away from us until we finally moved on. The trail switchbacks roughly a dozen times as it works its way up the east ridge coming finally to the Emerald Lake overlook with its gaping view down into the Tyndall Gorge and across the Front Range to Longs Peak. After that, it cuts back in a northerly direction across an open slope, with views to the Mummy Range, before bending around onto a northwestern slope that looks across to Notchtop and down into the Odessa Gorge. It was along this stretch that I started to feel some exhaustion. Some people are active all winter, snowshoeing here and there, embracing the strong winter winds. I'm more like a pika. Pikas do not hibernate during the winter months, they stay active, but also they stay sheltered in their rocky burrows grazing on the haystacks they gathered the previous summer and emerging now and then when the weather is favorable. So for me coming out of the winter months, I like to start off with some lower elevation moderate hikes to regain my summer legs. We were pushing against a steady and relentless head wind. I had pulled the hood of my wind jacket up and the steady roar of the wind with the constant flapping of the hood was starting to get to me. But I knew the horse tie-ups’ area was ahead and that is typically a good area to catch a snack break before the final push to the Flattop summit, so I used that as my goal to press on. But as Jonathan up ahead approached the spot, he continued on heading up, making clear his intention to continue. He had stayed pretty active all winter and was already hiking well. He kept hiking a little ways farther up before stopping and waiting while I chugged my way up to him. I halted and glanced up. “Beautiful day!” he declared with a big grin. I had to agree. The sun was out and the scenery was spectacular. I nodded my head in agreement, wondering when we would take a break. He described a spot between Flattop and Hallett Peak at the head of the Tyndall Gorge where we could take a wind shelter break behind a giant boulder. That became my new goal. We plodded our way up the snowfield and then rolled over the rounded summit of Flattop. A trail sign indicating the direction of two trails that head for Grand Lake is the only thing that serves as a summit marker. We took a brief pause in the flapping wind to take pictures, looking off to the west toward the Never Summer Range. We had not seen anybody else for the last mile. Pushing our way in a southward direction, we fought staunch westerly winds pushing us east. As we approached the top edge of the Tyndall Gorge, the winds gusted, roared, and became even stronger as the air flow began to funnel its way down toward Emerald Lake. I stumbled from rock to rock, following Jonathan when he stepped down into a wind eddy of a giant boulder, and just like that the conditions changed. No more push from the wind. No more rattling from my hood. I felt tremendous relief as I dropped my pack and adjusted a flat rock to sitting on. Pulling out our water and food stuffs, we had a perfect view of the west slope leading to the summit of Hallett Peak. The winter winds are so relentless during the winter months on the divide that they had not allowed for any snow to accumulate and we could see we had an unobstructed approach to the top. There was no reason not to continue our trek to the summit of Hallett, if we wanted to. But as I sat there resting, I could feel a drowsiness settling in and my eyelids felt heavy. I was quite sure that I could push myself to the top, but then there was still the descent back to the car to be considered. I settled in a little more on my rocky chair. I was at a decision point. Suddenly, Jonathan hopped up and started preparing his pack. He was ready to take it on and I almost followed suit. But then I said he should go ahead; I needed a rest. Both of us knew that splitting a group is not always a good decision, but I assured him from where I was that I could watch his progress and would be ready to go when he got back. He took off like a raven catching a strong tail wind. I took off my wet shoes and socks and laid them in the sun, then rummaged in my pack for a pair of dry socks. That felt good. I nestled back into my rocky aerie and soon dozed off for maybe 10 mins while Jonathan made his way up. I awoke and found him topping out and then watched his descent. It only took him 23 minutes to get up and 20 minutes to get back down. As I got myself ready to meet him on the divide, I knew I had made the right decision. I felt ready if not refreshed. I popped out of the eddy and back into the gush of wind. Then, we began our hike out.  Dave Rusk has been sauntering and taking photographs through Rocky Mountain National Park for decades. He is the author publisher of Rocky Mountain Day Hikes, a book of 24 hikes in Rocky, and the website of the same name. He is the publisher of HIKE ROCKY Magazine and an important content contributor to all of these endeavors. The publication of this piece of independent and local journalism was made possible by Rambo's Longhorn Liquor and the Country Market of Estes Park.

Story and photos by Marlene Borneman Editor's note: this piece is included in the article, "Three of the Best Wildflower Hikes in Rocky," by Marlene Borneman, published in the June/July edition of Hike ROCKY magazine. WEST UTE TRAIL Mileage: 9 miles round-trip (one way 4.5 miles) Elevation gain: 1,038 elevation loss one-way; 1,038 elevation gain round trip Rating: Easy one-way and Moderate round-trip Life Zones: Alpine/subalpine Peak Bloom: July-August The hike begins across from the Alpine Visitor Center (AVC) at 11,796 feet and ends at Milner Pass 10,758 feet smack on the Continental Divide! It is an approximate 23-mile drive from the Beaver Meadows entrance station to the Alpine Visitor Center. From the Grand Lake park entrance, go north on US 34 for 20.2 miles to the AVC. Milner Pass is 4.3 miles west from the AVC on Trail Ridge Road. There are restrooms at the AVC and at Milner Pass. A pleasant way to do this excursion is with a car shuttle making this a one-way trip. This avoids uphill gains and retracing steps. Place a car(s) at the Milner Pass Trailhead. One car brings the driver(s) back up to the AVC to begin the hike. This is one of my choice hikes to view a variety of exquisite alpine and subalpine wildflowers. In addition to wildflowers, marmots, pikas, snowshoe hares, and elk are often seen. Another bonus is spectacular views of the Never Summer Range. I never tire of this hike.  Alpine clover Alpine clover Start hiking by crossing Trail Ridge Road at the AVC parking lot to the obvious trail southwest. The trail crosses the expansive alpine tundra taking in alpine clover, dwarf clover, Parry's clover, blackhead daisy, alpine sunflower, American bistort, mountain dryad, spotted saxifrage, alpine stitchwort, alpine parsley and loads more. In July, the petite elegant snowlover can be abundant and a treasure to find. Cushion plants, champions of the tundra, are at home here boasting their fortitude against the elements. Moss campion, alpine forget-me-not, and alpine phlox are a few of these sturdy plants to be seen on this trail.  Pika Pika There is a short uphill section within the first mile reaching a rocky depression on the left (east) side of the trail. These large rocks shelter pikas and marmots. The pika's favorite food, alpine avens, is plentiful on the tundra. Pikas do not hibernate so they must gather food all summer to store in their hay piles to sustain them in the winter. Just beyond this spot the uncommon gold bloom saxifrage forms a bright gold carpet. I enjoy taking time with these flowers, getting down low with my hand lens to see the tiny golden spots on each petal. Arctic gentians add to the mix anywhere from mid- august through October. Many species of paintbrush flaunt the tundra with various shades of red, magenta and pale yellow. An often overlooked plant on the tundra is sibbaldia. The common name is cloverleaf rose. Sibbaldia has tiny yellow flowers and leaflets that resemble a three-leaf clover. Also often passed by are two ground hugging willows, the alpine willow and snow willow. They often grow side by side. One way to tell them apart is by their leaves. The alpine willow has broad bright green leaves with pointed tips and a deep mid-vein, whereas the snow willow leaves are rounded on the tips with a prominent netted vein pattern. The tiny flowers (catkins) lie within the leaves. Farther on to the east, three pristine tarns create peaceful spots for burnt-orange false dandelion, pinnateleaf daisy, dwarf goldenrod, subalpine daisy, dwarf chiming bell, Whipple's penstemon, starwort, mountain laurel, rose crown and king's crown. In August, start looking for several species of gentians in this area. Arctic gentians add to the mix anywhere from mid- august through October. Many species of paintbrush flaunt the tundra with various shades of red, magenta and pale yellow. After hiking approximately 2.3 miles you come to Forest Canyon Overlook. This marks approximately a halfway mark for the hike. In this area you may see Parry's lousewort, pale agoseris and Coulter's daisy. Heading down, the trail often becomes muddy from melting snow. Striking pink elephanthead fills the moist meadows. Before mid-July you may even find snow along this part of the trail. As the trail levels out, remaining muddy from the snow melting above and the many rivulets of water coming down the steep slopes above, watch for gray angelica, brook saxifrage, alpine speedwell, Hornemann's willowherb, marsh marigold, and globeflower that enjoy this damp habitat to the fullest. A strange appearance in wet areas is the bishops cap. Another find here in late July-August is the fringed grass-of-Parnassus. If you are there at the right time, waves of brilliant yellow come into view with the arrowleaf ragwort. There are a few stream-crossings to negotiate along here, too. As the trail drops farther into subalpine forest, look closely for the tiny plants in the Heath family; one- sided wintergreen, pyrolas, and wood nymphs sheltering under foliage. After 3.8 miles at the signed Mount Ida Trail junction, swing right for approximately 1.0 mile down to Milner Pass. Along the switchbacks, robust masses of heartleaf bittercress show off brilliant white petals. Jacob's ladder, hooked mountain violet, spotted coral root orchid and the more elusive wood nymph grace the forest floor. At this juncture, columbines, bracted alumroot, strawberry blight, and alpine sorrel can also be seen among the crevices. In August, blacktip senecio will be seen in abundance along the stretch of trail following the Poudre Lake shore all the way to the trail head. Take time to look under the flower head and see the black tips on the phyllaries. Purple fringe and paintbrushes are also in the assortment of flowers along Poudre Lake shores down to Milner Pass.  Massive bull elk near Poudre Lake (near Milner Pass). Massive bull elk near Poudre Lake (near Milner Pass).  Marlene has been photographing Colorado's wildflowers while on her hiking and climbing adventures since 1979. Marlene has climbed Colorado's 54 14ers and the 126 USGS named peaks in Rocky. She is the author of Rocky Mountain Wildflowers 2nd Edition, The Best Front Range Wildflower Hikes , and Rocky Mountain Alpine Flowers. The publication of this article was made possible by Rock Creek Pizza of Allenspark and Castle Mountain Lodge of Estes Park, supporting local and independent journalism.

|

Categories

All

|

© Copyright 2025 Barefoot Publications, All Rights Reserved