|

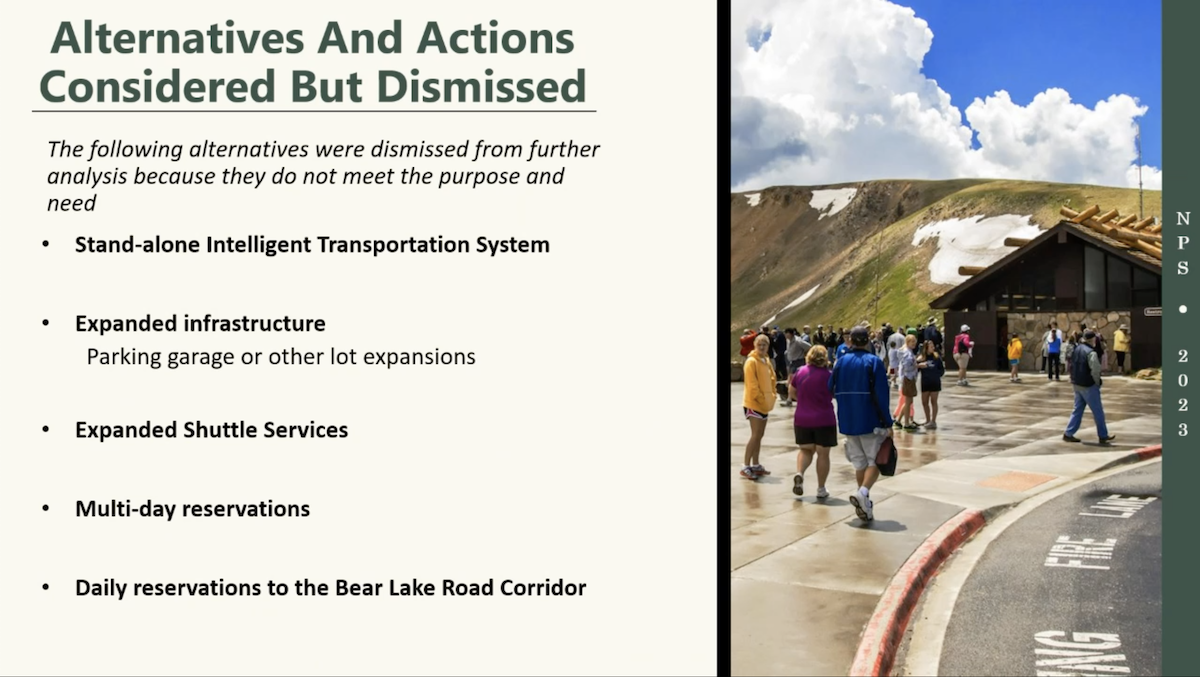

The slides below is information presented during the Virtual Public Meeting on the Environmental Assessment for the Long-Range Day Use Visitor Access Plan, on November 8, 2023. The intent of the presentation is to provide opportunities to learn more about the purpose of the project, key ideas, issues of concern, desired conditions for the park’s long-term day use visitor access, potential management strategies, ask questions of NPS staff and get information on how to provide formal written comments through the Planning, Environment and Public Comment (PEPC) website. You are invited to learn more about the park's Day Use Visitor Access Plan and Environmental Assessment (EA) by viewing a StoryMap and reviewing the EA at https://parkplanning.nps.gov/ROMO_DUVAS.

2 Comments

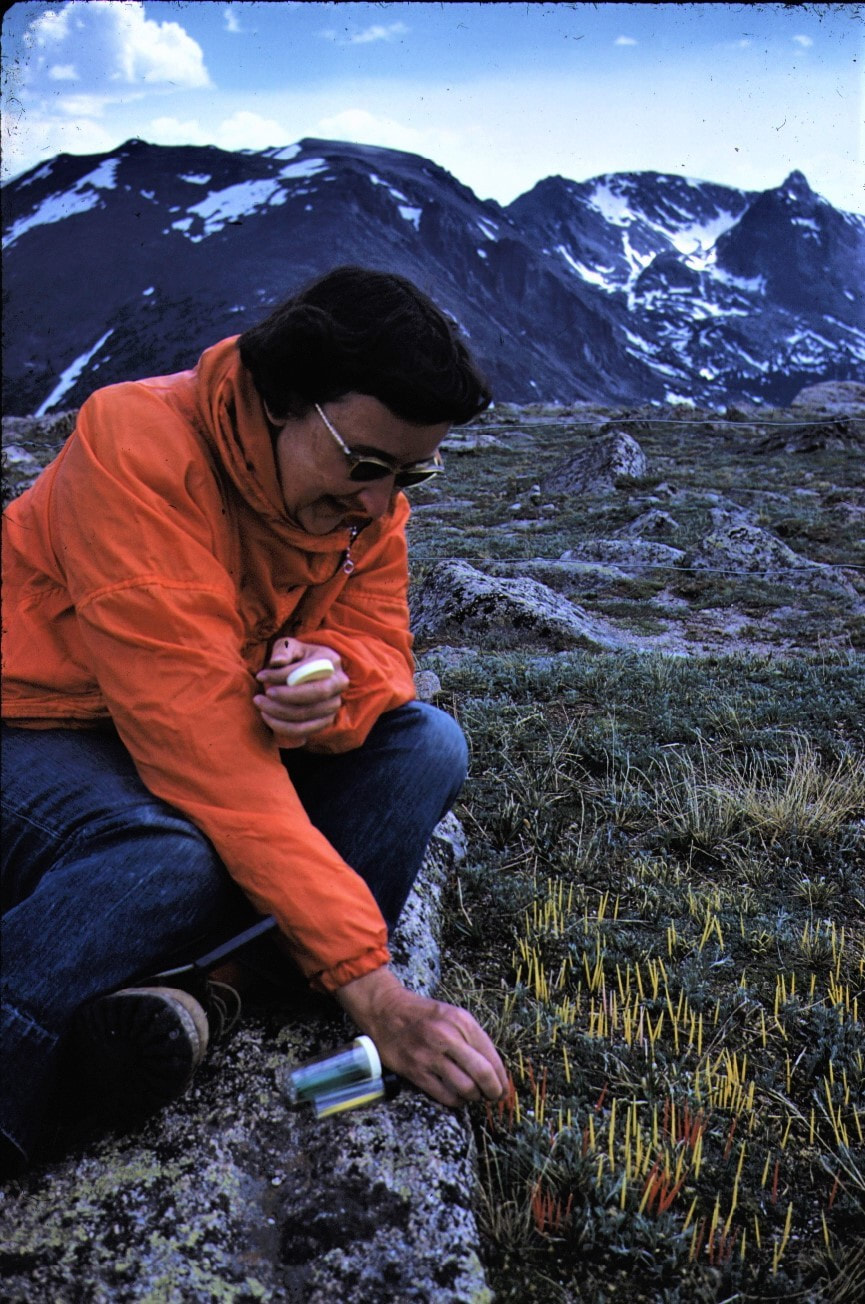

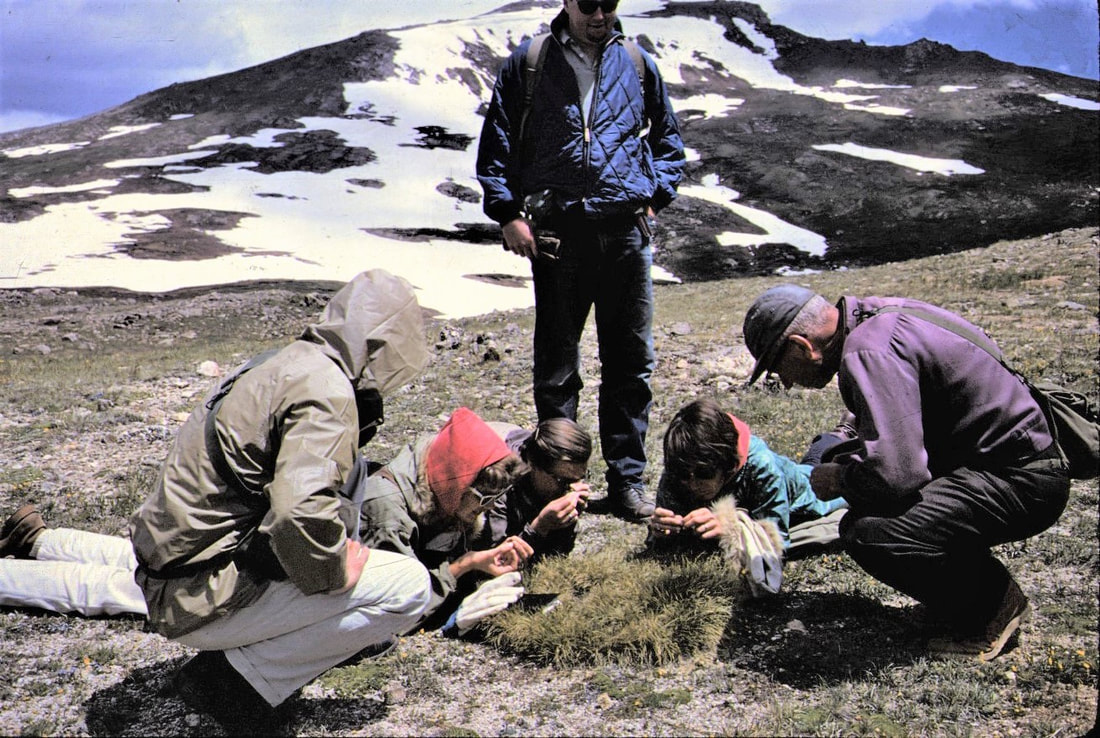

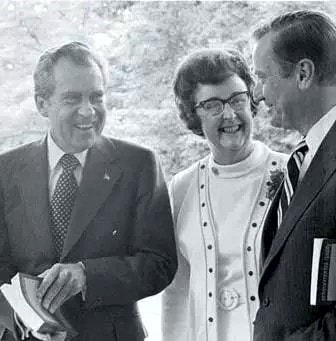

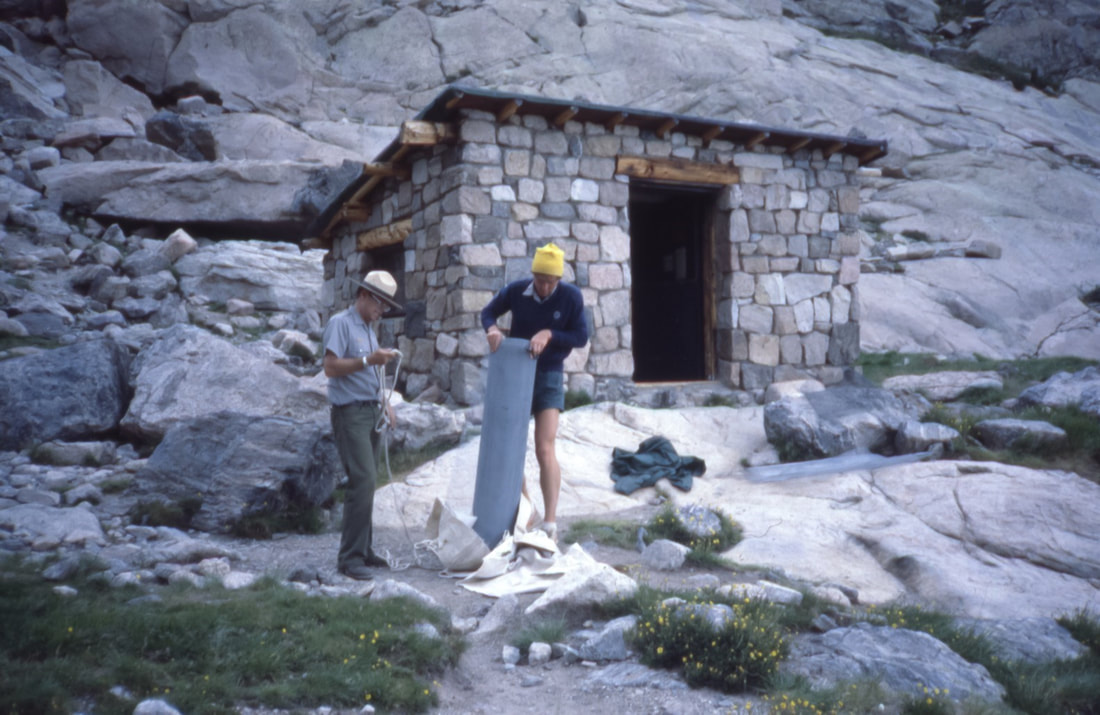

It is illegal to walk on the tundra in Rocky Mountain National Park at Fall River Pass, Gore Range, Rock Cut, Lava Cliffs and Forest Canyon Overlook. For reasons which will be explained, concentrated visitor use atthese areas poses a proven threat to the delicate tundra. HOWEVER, other areas of the alpine tundra, which is one-third of the Park's terrain, can be traversed upon; albeit, very lightly. Walking is not the preferred way to study this ecosystem up close. “Belly Science” – first developed by Bettie Willard – puts you on the tundra face down, spreading your weight across plants that have survived the harshest of climates for hundreds of years. The ground is surprisingly soft and supple, even furry in places where fine white hairs grow over leaves and petals, protecting each tiny plant from hurricane- force winds and near-freezing overnight temperatures. Fragrant, floral, clean and airy: the smells of the tundra are reserved for those who have the audacity to stick their noses into it. (see Rocky Mountain National Park’s policy on tundra use) This is a world where the smallest of organisms create a community of symbiotic relationships, each plant working with each pollinator to help feed its neighbors and expand vegetation above treeline, a world where roots run deep and plants stay short, with impossibly- bright blooms spreading out to hug the horizon, all the way up to the vertical end of the world. Respecting this world is paramount and understanding its legacy is just as profound. Bettie Willard's National Park work Bettie Willard always dreamed of being a National Park Service ranger, especially after she attended the Yosemite Field School in the summer of 1948. For that entire summer, she and other attendees lived in tents and worked in the wilds of Yosemite National Park, studying nature up close. Graduates from the field school – 16 men and four women – were then interviewed by the National Park Service, but Bettie's dream of being a ranger was dashed: “Don't you know? We don't hire women for those positions,” she was told. It didn't matter that she had just graduated from Stanford University with a degree in biological sciences or that she already had a lifetime of experience guiding through the wilds near Mammoth Lakes, California, where she spent summers with her parents. It only mattered that she was female. Willard dealt with mid-Century norms for women throughout the rest of her life but this environmentalist was not daunted. She had made an influential friend: Dorr Yeager, Rocky Mountain National Park's first naturalist and author of the “Bob Flame, RMNP Ranger” novels. Over the next several years, he asked around and found only four National Parks that were willing to hire women; one of these, Lava Beds National Monument (est. 1925), finally hired her as a ranger for the summer of 1952. The following summer, she was a ranger at Crater Lake National Park (est. 1902). When asked later in life how she got along as the only female ranger in those Parks at that time, she said that she did a lot of observation at first, finding out which rangers worked in which department or niche. Willard filled neglected niches, thus preventing stepped- on toes (and egos) of the more established, male rangers. She prided herself on complementing – not competing with – what the other rangers were doing. Between her undergraduate studies and this life goal achieved, Willard attended UC Berkeley to become a teacher. She taught in Salinas, then Oakland and finally general studies at Tulelake High School, located in California near the Oregon border. It was considered a rural school and eligible for the newly formed Ford Foundation educational grants. In 1954, she was awarded a $4,600 scholarship which “was enough for her to go to Europe for 14 months to study vegetation on the high mountains. She wanted to study the vegetation in the Alps, in Scandinavia and other places in Europe,” explained Leanne Benton, co-instructor for the Rocky Mountain Conservancy's “Bettie” Course: “Tundra Pioneer: the life and legacy of Bettie Willard,” held on July 20. Benton is a long-time Rocky Mountain National Park volunteer and taught this course with Cheri Yost, the current Park Planner for Rocky. While in Europe, Willard attended a conference of 2,000 international botanists in Paris and made valuable connections which led to several field trips in Switzerland to study alpine plants. “She also met a woman, Ruth Ashton Nelson, who was a Colorado botanist and had already published a book on the plants of the Rocky Mountain National Park,” Benton said. By the time Bettie was finished with her European studies and work, she knew she wanted to go to grad school and study American alpine plants, specifically to compare those with the plants she had studied in Europe. But first Willard had to fulfil the requirements of the scholarship by teaching two more years at Tulelake. In 1957, she enrolled in the University of Colorado at Boulder to study ecology. “Ecology really came into its own in the late 1890s and women were getting ecology degrees since the 1910s,” Cheri Yost explained. “But most women ecologists were either working with their more famous husbands, like Edith Clements, or they were teachers. They really weren't doing their own independent research.” But by the late 1950s Willard was doing just that, under the instruction of noted arctic and alpine ecologist John W. Marr. Willard wanted to study “plant sociology” (like she did in Europe) on the alpine tundra in Rocky. She established a plot at Rock Cut in 1958 that was 10 square meters large (current pipe fencing at Rock Cut includes her original plot). The same trail that she used through this area can still be seen, standing as a testament to the long recovery time for disturbed tundra. A second plot was established at the newly-built Forest Canyon Overlook. Her studies at several spots on Rocky's tundra led to the completion of her master's and then her doctorate, from the University of Colorado. “What she was noticing was that visitor use was having a huge impact on the tundra,” Yost said. Willard needed to convince Park managers that visitors were having an impact on this delicate area and that something had to be done about it. She thought the trails on the tundra should be paved and hardened, “if you pave a trail, people will stay on them,” was her argument. Next, she wanted Park managers to “stop the craziness in the backcountry,” because there were no rules about camping in the backcountry in Rocky. And finally, Willard wanted people to become stewards of the tundra through education and experience. She accomplished these goals by utilizing the skills, hard work and diplomacy that she had always applied working in the heretofore “man's world” of the National Parks. Visitor impact was proven through vast data sets – collected by Willard and others - that tracked alpine environments. Mission 66 (which was launched in the mid-1950s) provided the infrastructure funds to pave the areas she recommended, and her experience with backcountry “craziness” in her research both above and below treeline led to the establishment of backcountry camping permits in the early 1970s. Willard started teaching the first field seminar program in Rocky Mountain National Park, through the Rocky Mountain Nature Association (now the RM Conservancy). “She taught the alpine field seminar for many, many years in the Park,” said Yost. Willard was also instrumental in getting alpine rangers in Rocky to teach the public about the tundra and in the placement of signage and educational displays in the Alpine Visitor Center and other places. For 40 years, Willard came back to study her alpine plots every summer in Rocky, funded in part by the Department of Defense (since the country was still at war in various arenas). “She took photos of her plots, put toothpicks down to mark the individual plants, and tracked those plants for the entire time she worked in Rocky,” Yost said. Today, Jackson Maldonado, Alpine Community Science Intern, is continuing Bettie's work in much the same way. This summer was the kick-off of a continuing community science project that will encompass two programs: one with trained volunteers doing surveys at Willard's original plots and the other program designed for community members. It will teach them about climate change effects on the tundra, and the phenology (or life-cycle) of tundra plants and include an excursion onto the tundra to identify its wildflowers. “If we can get a solid data set that builds off of what Bettie started, we can really track the impacts climate change is having on the tundra,” Maldonado said. He spent much of the summer working with Park employees to create the parameters, logistics and study scope of the project, which will kick off its first year of serious study in the summer of 2024. Bettie's "experiments in ecology" But Bettie Willard's story doesn’t end with her important conservation work in Rocky. She wrote Land Above the Trees: Guide to American Alpine Tundra with Ann Zwinger in 1971. “This book was instrumental while I was learning about the tundra as an RMNP ranger,” said Leanne Benton. Moss campion, a cushion plant, is one of the “champions” of the tundra, Benton said, growing only about ½ inch by the time it's five years old. “It doesn't really start to bloom unless it's about 10 years old and by the time it's 20-25 years old it's about 7 inches wide and blooming profusely. “Think about what a grinding footstep can do to a plant like this,” Benton said. After Willard achieved her doctorate, she stayed in Boulder and helped to found the Thorne Ecological Institute. In 1965, she became its Executive Director, in 1967, she was its vice president; and, in 1970, president. “Thorne's mission was to help people understand the relationships in the environment and develop a personal concern for the Earth,” explained Cheri Yost. “While Willard was at Thorne, it put her at the forefront of many environmental partnerships.” Willard went on to form and/or serve with numerous environmental organizations throughout the state, excelling at collaboration. “In 1966, she created what she called 'the experiment in ecology,' ” explained Yost. “She really believed that all of these conversations were a three-legged stool: engineering, economics and the environment. If you could not get these three concerns to talk to each other, you are not going to be successful stewards of health and society.” Working with the mining industry along with environmental concerns in Colorado, Willard created “a safe space to work out differences so meaningful and lasting agreements could be made,” Yost explained. “We fostered abundant measures of openness, objectivity, willingness to tell all, an ability to listen and believe but to question until Truth comes forward,” Willard said of this time in her life. Working for the Federal Government In 1969, Congress passed the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), which codified Willard's “experiment in ecology,” on a national level. Its mission was to bring every new environmental policy in front of everyone who would be affected by it. The next year, President Richard M. Nixon appointed Willard to the President's Council of Environmental Quality (CEQ). She was the first woman to serve on this council, which existed to educate everybody in the country on NEPA. “Most of the environmental laws on the books today were put in under the Nixon Administration,” explained Yost. Willard received many letters of congratulations for her service with the federal government, but nearly every one of them contained some back-handed compliments, essentially: “pretty good – for a woman.” For the rest of her life, Willard went on to champion common-sense environmental laws in Colorado and nationwide. For example, said Benton, there were several things that Willard did to help mitigate the environmental issues with the Alaskan Pipeline during its NEPA process. “She made about 15 trips up to Alaska during that time to look at the route planned for the pipeline and was instrumental in getting the pipeline raised above areas of permafrost (so it wouldn't melt) – and raised high enough to not interfere with caribou migration.” Willard was not against development. “She worked for Nixon, she was a Republican,” Yost said. “She was the head of the Colorado Olympic Committee in 1970 when Denver was awarded the 1976 Winter Olympics. She didn't have any concerns about the Olympics itself, she had a problem with the necessary, uncontrolled building that was going to happen next to it.” Ultimately, voters in Colorado voted against holding the 1976 Winter Olympics in the Colorado Rockies, making it the only state to ever refuse the offer. Bettie returns to Colorado to educate on environmental issues in the state Bettie Willard returned to Boulder after the change of administration and after a few years, “she was approached by the Colorado School of Mines, one of the foremost mining schools internationally, to set up a department of environmental sciences, looking at how to mitigate the effects of mining,” Benton explained. When she was interviewing for the job, she asked the president of the board: 'How do you feel about working with a woman?' She accepted, but only after being assured that anyone exhibiting chauvinistic behaviors would not be tolerated at the school. She developed the brand-new department and created 28 classes, many of which she taught herself. Thirty- two students graduated with the Minor degree she designed, but still, she didn't feel equal to her fellow professors. “She felt some type of discrimination,” Benton said. In 1982, she took a leave of absence: two years without pay. Nevertheless, she traveled, cross-country skied, taught, and wrote books (many of which are some of Benton's most treasured possessions). When it came time to return to the School of Mines, she just didn't want to and “resigned” in 1984. For the rest of her life until she was no longer able, Bettie Willard wrote books, taught, served on groups and committees and taught seminars. “She taught seminars here (for the Rocky Mountain Conservancy) until 1996,” said Benton. “I was able to take a course from her in 1995,” Benton recalled. This experience really cemented Benton's commitment to Rocky. “She was a very gifted teacher,” Benton said. Bettie Willard passed away from Alzheimer's disease in 2003. You can continue Bettie's legacy at Rocky! Jackson Maldonado is looking for some people to practice Belly Science with him next summer, through his Alpine Community Science projects. You can reach him with questions at [email protected]) Like Willard, Maldonado dreams of working for the National Park Service after he graduates. “I would love to make Parks more accessible, everyone deserves to be in green space, to experience nature, safely.” He admires Bettie Willard very much. “The work that she accomplished locally, regionally and nationally positively impacted so many people and the environment.” (Maldonado's views do not necessarily reflect the goals and ideas of the National Park Service.) Like Bettie, Leanne Benton grew up in California. In college, she took a summer Park Ranger job at Rocky; “It was a life-changing summer – I loved the work and the Park. For four more summers I worked as a seasonal Park Ranger on the west side. I met my husband one of those summers who was also a Park Ranger.” After years of working as a full-time Park Ranger for several NPS units, Benton returned to Rocky to manage the Alpine Visitor Center for eleven years. She continues to volunteer with Rocky.  “In Land Above the Trees (1972), Bettie Willard and Ann Zwinger brought together most of what was known about alpine tundra in the U.S., including Bettie's research, and presented it in a book that was understandable for a wide audience,” Benton said. “The book was a huge success. The information so poetically presented in the book illuminated the fascinating adaptations of the plants and animals for survival in the alpine world. Land Above the Trees was THE BOOK that all the park rangers read to learn about alpine ecology so we could effectively communicate with the public. This book continues to be relevant today. The results of Bettie's research and recommendations also laid the foundation for how Park Managers protect the park's tundra, while also allowing public enjoyment of the tundra. Bettie also recommended the importance of education in protecting the tundra.” Benton wants you to remember that while traveling on the tundra, move like a herd of elk, not a line of people. Step on stones or gravel where possible and if there is a trail, use it. Cheri Yost has spent most of her NPS career translating science, which is how she was introduced to the remarkable legacy of Dr. Willard. She is currently the Park Planner.  Barb Boyer Buck is the managing editor of HIKE ROCKY magazine. She is a professional journalist, photographer, editor and playwright. In 2014 and 2015, she wrote and directed two original plays about Isabella Bird and Rocky Mountain National Park, to honor the Park’s 100th anniversary. Barb lives in Estes Park with her cat, Percy. memoir and photos by Chris Reveley, Longs Peak Ranger 1979-1981  Bert McClaren and Chris Reveley unloading supplies in front of the (now-gone) Chasm Meadow cabin. The structure was used for many years as a cache for rescue gear; there were ropes, a litter and climbing hardware. There were also four bunks and old army surplus sleeping bags, in case rescuers had to spend the night. Climbing rocks, ice and big snowy mountains is dangerous. Sometimes people get hurt and occasionally they die. The job of search and rescue (SAR) first-responders is to deliver to the injured an appropriate level of care as efficiently and safely as possible without making matters worse. In the case of fatalities, body recovery is pursued whenever and wherever possible as long as the risks to SAR personnel are minimal. As in most of the U.S., SAR services in RMNP are available anytime, day or night, in all seasons. Those who do this work may be trained specialists employed by the Park, highly skilled individuals from the community who are called upon as-needed or qualified volunteers. They may reach the needy on foot, in vehicles, in boats or aircraft. In RMNP, SAR has taken place primarily on higher mountain terrain, though rescues and body recoveries in and around fast-moving water at lower elevations also occur. At times, cooperation with other SAR groups and the military has proved very valuable. For more than a century, Rocky has been fortunate to have a pool of highly skilled rock climbers and mountaineers close at hand, within the population of local instructors and guides. Recognized as valuable assets by Park managers, these individuals have frequently been called upon to assist with or sometimes direct SAR missions on highly technical terrain. Some of these experienced alpinists have found full-time employment and long-term careers with the NPS in Parks with traditionally high levels of technical climbing activity: Denali, Mt. Rainer, Yosemite, Teton and RMNP. This was the path that led me to the Longs Peak Ranger Station in 1978. Mountaineering hazards come in two primary flavors: objective and subjective. Objectively, mountains present variable surface conditions and atmospheric changes that when combined, can contribute to life- threatening situations. What's commonly called “bad luck” is often a feature of the predictably unpredictable and unstable mountain environment. Subjectively, climbers bring to the mountains various levels of experience, skill and judgement. With consideration of all possible variables and realistic assessment of a party's strengths, weaknesses and goals, climbing trips tend to turn out well. Poor planning, bad decisions and inadequate preparation are common contributors to bad outcomes. In the spirit of boldly going where others have not, mountaineers sometimes press on in the face of adversity and exhaustion to accomplish great feats. Our heroic dreams are egged-on by the human (often, male) endocrine system to lead us down harrowing, narrowing dark holes from which adrenaline and testosterone will not rescue the foolish. Just as aircraft disasters can sometimes be traced to a series of mis- judgements and bad decisions, analyses of mountaineering disasters often reveal a trail of errors from which we can all learn valuable lessons. Successful rescues of the injured are sometimes the product of one person's quick, decisive action. More often, they result from the work of a well-coordinated team with wise, experienced leadership and skilled, hard-working foot soldiers. One early summer morning in the late 1970s, I was visiting with campers at the Boulderfield site on Longs Peak when I received a radio call: a Park visitor hiking in the Chasm Lake Cirque had reported calls for help from “somewhere on the East Face”. I went over the ridge between Mount Lady Washington and Longs Peak, past the Camel formation, and descended into the Cirque. Shouting was actually coming from the Broadway ledge at the base of the Diamond on Longs Peak, one of the largest high-altitude walls in the U.S. and a popular destination for experienced rock climbers. I climbed the North Chimney on the Lower East Face and reached Broadway about 30 minutes after receiving the radio call. A climber had fallen from the poorly- protected, horizontally-traversing section of the so- called “casual route,” sustaining blunt trauma to various body parts in the long, pendulum-like fall. He was alert, moving all limbs and seemed fully oriented to the situation. Most worrisome, however, was his report of intense back pain between his shoulders. A quick exam revealed a very red, very swollen, tender-to-touch area over his mid-thoracic vertebrae. Back in radio-contact with the dispatch office, I asked them to mobilize the Park rescue team. Gathering rescue team members and necessary equipment was accomplished quickly at Park headquarters. The first members of the rescue group began to appear at the east end of Chasm Lake a few hours later. Leaving the injured climber warm, fed and watered in the company of his partner, I climbed back down the North Chimney and joined the team to help establish a line of fixed ropes up to Broadway. This allowed the dozen or so members of the team to ascend safely, carrying packs filled with ropes, climbing anchors and the two-piece, metal litter in which the injured climber would be lowered several hundred feet down the steep lower East Face. They also carried bivouac gear in case we had to spend the night. The day went by quickly. We established a safety zone for all the rescuers and built a multi- component, equalized anchor for the litter evacuation. The climber was placed in the litter and positioned without pressure on the injury. One of the Park's most experienced paramedics, Frank Fiala, secured himself to the litter's frame at the climber's head. I took up a position at the feet. Shoulder-mounted radios allowed us to communicate with those managing our descent. Mostly, we requested slack in either the head or foot line in order to keep the litter in a slightly head-up/foot- down orientation. The lowering took more than an hour. On the way down I remember feeling pretty good about the whole situation: On the litter, all three of our lives depended on expert management above. Charlie Logan, an experienced, long-time Ranger was in charge on Broadway; very comforting. The weather was holding, the injured climber was comfortable and not reporting worsening symptoms and we learned that Bob Greeno, a legendary helicopter pilot would be flying in for the rescue. Rumor had it that Bob had taken part in the “Helicopter Olympics” in Russia. None of us knew exactly what that meant but it sounded impressive. In 1967, he had rescued five survivors of an airplane crash, high on the slopes of Mount Sherman in Colorado. The feat was described by FAA officials as “…the most daring and spectacular mountain-top 'save' in aviation history.” Several of us had worked with Greeno and we valued his great skill and excellent judgement. Winds in the Chasm Cirque were constantly variable and tricky. The helicopter's only possible landing zone (LZ) was a large, flat boulder just below the snowfield under the lower East Face. A collective expression of joy and relief went up from the assembled rescue team when we heard that Bob was on his way. But darkness was approaching and we started to worry. It felt like time was of the essence with the climber's serious injury. We feared that bleeding or the swelling of soft tissue around the damaged vertebrae might impinge on his spinal cord and lead to permanent damage. At first, the little Alouette Lama helicopter sounded like a bumble bee as it turned west and started up the valley far below Chasm Lake. Within minutes, Greeno was hovering above us, surveying the LZ. The “large, flat boulder” suddenly looked smaller and a little tilted. If he couldn't execute the landing safely, he would have to leave, no negotiating. The helicopter danced directly above us as Bob tested the winds and viewed the LZ from several different angles. We were all hidden beneath the boulder's edge, well protected (in case things went very bad) but ready to approach the aircraft once he landed and gave us the thumbs up. Then, rather suddenly, down he came, placing both of the helicopter's skids perfectly on the exact center of the boulder. I peeked up over the edge. He nodded slowly and waved us in. The whole loading operation took about one minute. The litter with its precious cargo barely fit in the small aircraft. We stepped away, toward the helicopter's nose where Bob could see us and then…he was gone. Twenty minutes later Bob delivered the injured climber to a Denver hospital. Back in the Chasm Cirque there were cheers, tears and hugs. It had been a long exhausting day, physically and emotionally, and we all fell asleep easily amidst the rocks. Somewhat rested, we hiked out the next morning at first light. It was the next summer that the injured climber returned to the Longs Peak Ranger Station to thank us. He was fully recovered. Out of respect for the families of those who did not survive accidents, I won't speak about specific incidents here. I can write about the effects those searches and body recoveries had on me. Like many baby boomers raised in the middle-class suburbs of American cities, I had little first-hand experience with death. When we signed up for SAR work around Longs Peak, no one talked about the high probability that we would be searching for and retrieving severely damaged human bodies as a routine part of the job. I approached every response to a likely fatality with a degree of hesitation and an uncomfortable mixture of purpose, fear and anger. Indeed, this was part of a job I had accepted and I was duty-bound to proceed. I was reminded and frightened by how easily a moment of inattention or the choosing of a wrong path could lead to the end of a life in this environment where I moved so easily, perhaps a little too comfortable with the ever-present hazards. I was angered by those instances where the death was a result of negligence, ignorance and poor judgement on the part of the individual or those who were relied upon as leaders. And, I was stunned, thinking about the lifelong psychological and emotional pain the families would endure. I remember details of every one of those body recoveries and as I've passed by some of those locations in the last 40 years, I paused each time for a moment of sad reverence. For me, the deaths of children were always the most difficult to confront and process while going about our work.  Chris Reveley has spent 50 years climbing and doing endurance sports; and, thirty years learning and practicing medicine. “Now I’m a Happy House Husband with hobbies,” he said. The publication of this article from the April/May 2023 issue of HIKE ROCKY magazine was made possible by Inkwell and Brew and MacDonald Book Shop

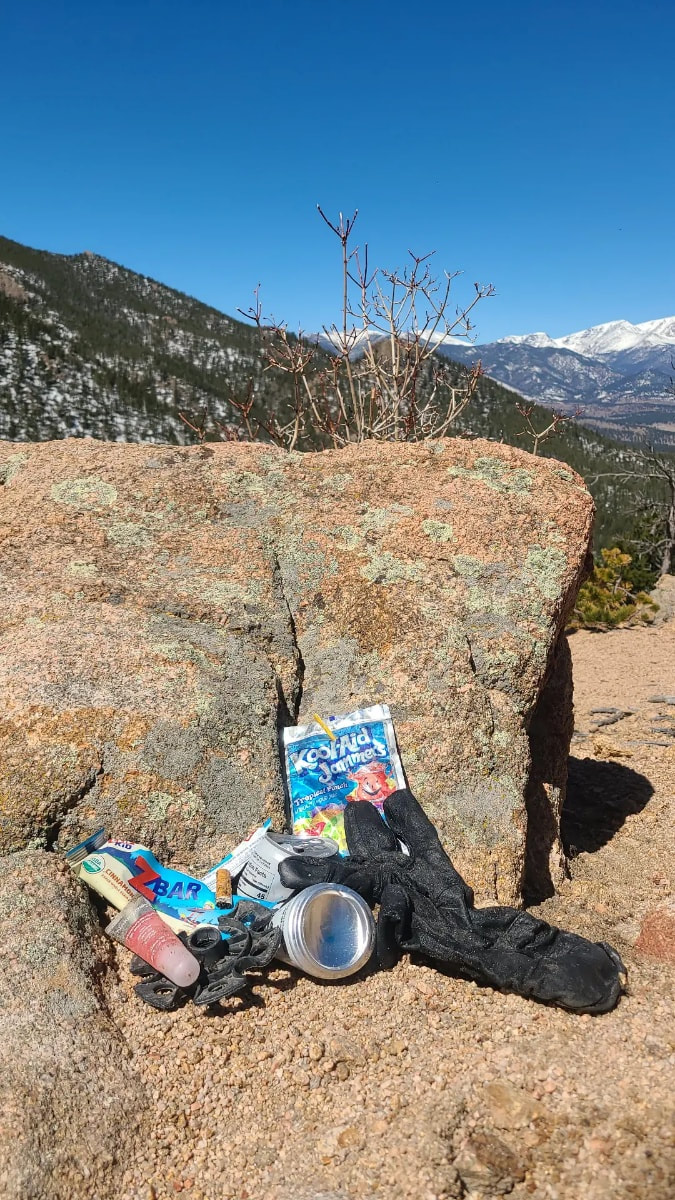

The Mad Moose and Xplorer Maps This story was pulled from the most recent issue of HIKE ROCKY magazine, which published April 30, 2023. For more information click here photos and story by Bronte Brooke As we move out of April, the coming of spring is evident. The change of the season brings life back into the mountains. In town, elk can be seen out and about. Fresh green grass pokes its way through the snow. Birds welcome the morning with song. The mother osprey at Lake Estes teaches her young to fly. People scatter the trails with friends and family. The snow melts and the weather warms, drawing eager admirers into the Rocky Mountains. But the reality of this influx of travelers has a flip side as well. As electric and alive as the wilderness feels with the surge of onlookers, it also leaves more room for mistakes. Last week while enjoying a sunset walk along Lake Estes, I noticed quite a bit of trash washing onto the shore. What started out as a leisurely stroll quickly transformed into an intentional trash cleanup after observing just how much scattered the trail. Then it occurred to me: more people outside means an increased risk for trash to be left behind. Whether it be families on picnics, anglers passing the time or hikers enjoying a snack after a long hike, there is an increased potential for things to be left behind in the outdoors. It's unfortunate, but it happens. I think we're all guilty of it. We stuff a granola bar wrapper into our pocket planning to throw it out later, but the wind grabs hold of it without us noticing. Or we get distracted photographing an elk and forget the cup of coffee we left sitting on the rock beside us. Mistakes happen even if we have the best intentions to clean up after ourselves. I'm hoping this serves as a reminder to make that extra effort to pack it in, pack it out. And if you notice a stray wrapper or broken piece of shoelace, take that extra moment to pick it up. We share this land with numerous different animals. The Rockies contain large herds of elk, a variety of birds, squirrels, chipmunks, deer and many other creatures. It's our responsibility to help protect this beautiful place they all call home. After what I saw on my walk around Lake Estes, I decided it was time to implement a change. In order to help maintain this Colorado oasis I've grown so fond of I've started integrating a new routine into my weekly schedule: trash cleanup walks. You can easily do this while already out hiking or plan a separate trip for it. Some things to consider bringing:

A quaint path circles the lake for a quick scenic stroll, but if you're looking for something slightly more challenging, Lily Ridge includes some more steep and rocky terrain. There are also a handful of other trails that can be accessed from the same trailhead, such as the Estes Cone for those seeking a real calf burner. But since the purpose of my hike was to cleanup trash in the park, I stuck with the more populated trails – Lily Lake and Lily Ridge. As I walked along, trash bag in hand, several people noticed my efforts and thanked me. It made my walk much more enjoyable, knowing I was doing something good for the planet and helping to maintain one of my favorite spots in Colorado. Trash items found on my walks: Lily Lake: Cigarette butts, granola bar wrappers, juice boxes, crushed cans, cough drop wrappers, chapstick, hair ties, used toilet paper, gum wrappers, chewed up gum, an old glove, disposable hand warmers, coffee cups and a children's shoe Lake Estes: A full tackle box, fishing line, chip bags, cigarette butts, Styrofoam, bait, pop bottles, pieces of plastic, candy wrappers, plastic water bottles and pieces of fabric amongst many other random scraps.  Trash items picked up around Lake Estes Trash items picked up around Lake Estes I think the hardest part about finding so much trash in the Park is knowing the negative affects it has on the local wildlife and our planet as a whole. I often see ducks at the lake with fishing line wrapped around their legs, wings or beaks. And as much as I'd love to help untangle it from their bodies, realistically it's nearly impossible to get close enough to do so. Birds and squirrels mistake trash such as gum or cigarette butts as food and get sick. Plastic items take decades to decompose, and frankly it draws away from the beauty of this amazing landscape. I was honestly shocked at some of the items I found, which is why I recommend bringing gloves or hand sanitizer on your cleanup walks; you never know what you'll stumble across. The amount of used toilet paper that I found at Lily Lake was truly atrocious, especially taking into account the fact that there are pit toilets at the trailhead parking lot, as well as numerous trash cans that can be found along the trail. Another item that stood out to me was the tub of bait at Lake Estes. I was about to throw it out when I noticed it was quite heavy and still felt rather full. Upon opening it up, I realized there were several live worms still inside. Seeing as the tub clarified they were local worms I found a soft patch of dirt and released them. The full tackle box also caught my attention. It had lures, hooks, and spare fishing line inside, perfectly intact. I hesitated to throw this item out, all still perfectly fine and usable. Instead, I sat it on top of the trashcan for another angler to find and utilize. That felt like the better choice instead of tossing it into the landfill to waste away and take years to decompose. I point these items out as an example of the things you'll stumble across, but also as an encouragement to take the extra step in thinking about how you dispose of the trash you find on your walks. Are there objects that could be recycled or composted? These are some of the things to consider. Maybe bring two bags with you; one for trash and another for recyclable items. Whether you implement intentional trash walks into your routine like I did, pick up items found while hiking or become more conscientious about packing it in and packing it out I hope this serves as a reminder to care for this wonderful planet we share. Have fun while doing it. Get out there! Bronte Brooke is an outdoor enthusiast, nature lover and adventure seeker. She’s spent the past two years living nomadically and traveling the states in her self-converted campervan with her two cats, Piper and Sotba. She unexpectedly found myself in Colorado this summer and haven't left since. Bronte is originally from the Pacific Northwest so she naturally fell in love with Colorado's landscape and the sense of "home" it's brought her. “The people I've met and the community I've built are what makes this place special to me,” said Bronte. The following business partners sponsored the publicaiton of this original content from HIKE ROCKY magazine: New Roots Real Estate, the Bank of Estes Park and Brownfield's

story and photos by Marlene Borneman this story was included in the 2023 Snow Play edition of HIKE ROCKY magazine “You're off to good places, today is your day. Your mountain is waiting so, get on your way.” - Dr. Seuss A spot with deep roots for winter adventures within Rocky Mountain National Park is long-loved Hidden Valley. At 9,240 feet of elevation and thick with Engelmann spruce and Subalpine fir, this narrow valley offered enjoyment in the snow long before it became known as a downhill ski area. As early as the 1930s, locals skied old logging skids and started make-shift runs. According to his book, Recollections of a Rocky Mountain Ranger, Jack Moomaw managed the National Championship Ski Races at Hidden Valley in the winter of 1937. The Colorado Mountain Club also enjoyed many ski and snowshoe outings there in those early years. The Hidden Valley Ski Area officially opened in 1955, providing ski lessons and rentals, as well as a cafeteria, lodge, an ice skating rink and daycare. Hidden Valley certainly filled a niche for locals and the Front Range communities. Local schools took advantage of Hidden Valley and loaded school buses with students for a day of skiing. The last season for the facility was 1991, when operations closed due to financial losses, lack of consistent snow conditions and the I-70 corridor opening access to larger ski resorts. All that remained were materials salvaged to construct the current warming hut and restrooms. Estes Park local Brad Doggett was part of the Hidden Valley Ski Patrol from 1979 to 1987. According to Doggett, there were no groomed trails or modern snow-making equipment when he started work at the ski area. What he appreciated most was the family- focused atmosphere for visitors and staff. Hidden Valley Ski Area provided local jobs and a gathering place to socialize with like-minded people and will always be close to Doggett’s heart. Hidden Valley is still a thriving location for a range of winter activities. Sledding is a popular activity for families and the only place within the park where sledding/tubing is permitted. Children and adults of all ages spend many hours tramping up the hills and swishing down on sleds and tubes. Backcountry skiers, snowboarders and snowshoers are also fond of the recreational opportunities at Hidden Valley. Ski runs from 30-plus years ago provide trails through the heavily forested terrain. The slopes west of the sledding hills are a perfect place to learn and/or practice backcountry/cross-country skiing and snowboarding. The Colorado Mountain School schedules many ski classes and avalanche courses on the higher slopes. Park Rangers conduct SAR (Search & Rescue) Training at Hidden Valley. In 2016, an avalanche beacon training park was installed at Hidden Valley to be used by the public and as a vital part of training for park staff. The purpose of the Beacon Hill is for skiers to practice their transceiver location and probing skills in case of an avalanche. This free service encourages the public to practice avalanche safety. A shovel, beacon and probe are essential avalanche rescue tools and should be carried by all backcountry skiers. (also, see last edition's story, Winter Safety in the Backcountry ) Walkers take advantage of the winter's beauty here. Picnic tables are in place for both summer and winter picnics. Building a snowman is a delight at any age. Many folks visiting from warmer states or countries are thrilled to experience sparkling snow for the first time. On winter weekends Hidden Valley is staffed by VIPs (Volunteers in Parks) fittingly designated “Sled Dawgs.” VIPs help folks locate sledding slopes and ski trails, open the warming hut, provide Park information, and assist in getting medical attention in case of accidents. The goal of a “Sled Dawg” is to provide information on “snow play” fun and safety at Hidden Valley. The Junior Ranger Program is a great addition this winter at Hidden Valley. Park Rangers present a variety of learning opportunities to all ages. Explorer bags equipped with binoculars, magnifying glasses, temperature gauges and informational pamphlets are available to future Junior Rangers. Rangers gladly answer questions about Rocky's wildlife, weather, geology and much more.  Hidden Valley is the perfect place to practice new skiing skills! Hidden Valley is the perfect place to practice new skiing skills! Be aware there are dangers in sledding, skiing, and snowshoeing in a wilderness area. Sledding accidents far outnumber accidents among skiers or snowshoers. According to Mike Lukens, RMNP Wilderness/Climbing Program Supervisor, years ago there were five ambulance runs from the sledding hill in one day! VIPs inform visitors of sledding boundaries, to be mindful of other sledders, and to remind them to walk up the sides of the sledding hill rather than the middle. These simple tips may help visitors avoid accidents. Hypothermia is a real threat. Adequate warm clothing and proper gear is a must. Don't forget sunscreen! The warming hut is a welcome bonus at Hidden Valley offering a heated indoor place to take time for rest; bring drinks and food to keep hydrated and energized. Even in winter months, there are opportunities for bird and wildlife viewing. Stellar’s jays, Clark's nutcrackers, gray jays, ravens, chickadees, woodpeckers, and turkeys are often seen throughout this valley. Moose, elk, and deer enjoy browsing along the willows that poke above the snow. Be watchful for coyotes looking for prey. All sorts of fun can be had at Hidden Valley in the chill of winter. So, layer on your warm clothes, choose your gear, and come play in the snow at Hidden Valley.  Marlene has been photographing Colorado's wildflowers while on her hiking and climbing adventures since 1974. Marlene has climbed Colorado's 54 14ers and the 126 USGS named peaks in Rocky. She is the author of Rocky Mountain Wildflowers, 2nd Ed, The Best Front Range Wildflower Hikes, and Rocky Mountain Alpine Flowers, available for purchase here. The publication of this piece of independent and local journalism was made possible by the Bank of Estes Park and Longhorn Liquor.

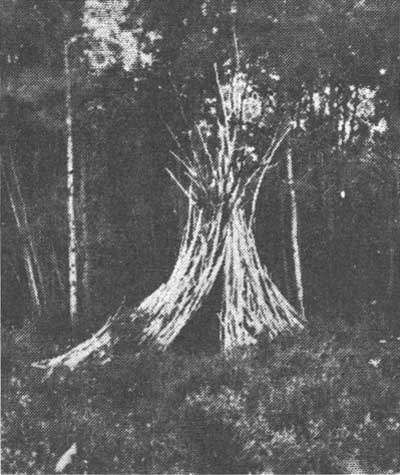

Research & story by Hillary Eichinger  Sprague family homestead in Moraine Park; NPS photo Sprague family homestead in Moraine Park; NPS photo Winter in the Rocky Mountains is harsh, often bringing sub- zero temperatures, frequent storms and high winds. Elk, deer and moose will move down to lower elevations during storms and freezing winds. So why then did early people continue to come back or choose to stay? The easy answer is the abundance of resources and vast sweeping landscapes. Fresh water, abundant wildlife and many wild edible plants attracted people to the dense terrain and high peaks. The Rockies, although severe during winter, provided enough food during the summer and fall to sustain human life. There have been people in the Rocky Mountains and surrounding foothills for more than two thousand years. The Ute Nation believed the creator god Sinawav (Sinauf) specifically placed them in the Rocky Mountains and at Mesa Verde as the chosen people while distributing the other groups of people around the globe. They were to be stewards of the land forming a close relationship to the seasons and changes of the area. The Ute people are not considered nomadic because they returned to the same places, year after year, depending on the season. The area from Denver and Cortez to the east, most of Rocky Mountain National Park and west to Northern Utah, and south to what today is Northern New Mexico were part of their territory. They defended the area fiercely but did not inherently seek battles with other indigenous people that would sometimes include the Arapaho, Cheyenne, Shoshone, and Navajo nations. They traded with Pueblo peoples in New Mexico for pottery to be used in food storage for winter.  “Chief Ouray, pictured here with his wife Chipeta, was one of the most influential leaders of the Northern Ute people in the late nineteenth century. A known intellectual and skilled diplomat, Ouray negotiated treaties and attempted to avoid conflict with whites wherever possible.” (coloradoencyclopedia.org) During the spring and summer months. the Northern Ute bands would break up into family units to return to certain wild crops and hunting grounds. They remembered specific berry bushes, seeded meadows, good places for fishing, and small game hunting areas to return to every year. They also planted seasonal crops like corn, western potato and squashes. The small family groups were careful not to overtax the land, making sure to not take an entire crop or overuse the soil. By leaving some food behind for Mother Nature to recover or for animals to eat, they cultivated the edible resources they would return to. The Northern Utes believed that they were owned by the land, rather than the other way around. They gathered wild mountain foods including chokecherries, wild raspberries, seeds from grasses and trees, pinenuts, and dried crickets. The yucca plant was very important as it was used for basket making, tea, pulp cakes and medicine. The inner bark of the ponderosa pine was harvested for its medicinal properties. It could be used as a compress, to fight infections and as a healing tea. The men would fish and hunt large game such as deer and elk while the women trapped small game like rabbits and ground squirrels and gathered wild berries and seeds. Bison were not hunted in abundance by the Ute Nation until after 1600, when they acquired horses from the Spanish.  Wikiup/NPS photo Wikiup/NPS photo During the late fall when the weather would start to turn cold, they would travel out of the mountains and meet up with other families. The large number of people allowed more protection from hungry predators and attacks from other tribes looking to get quick resources in the winter. The entirety of the band would gather together for the winter months in a few carefully chosen locations. The Northern Ute bands would camp along the White, Green, and Colorado Rivers in what is now known as Utah. This was a time of rejuvenation, food sharing and crafting. Elders would tell stories, pass on traditions, and arranging marriages. Women would make clothing, spending hours on intricate beading patterns that became famous and highly sought after among other tribes. Clothing and moccasins were typically made from animal hides, most often deer and rabbit. Families would stay together for the deep winter until the bear ceremony in the spring, which marked the time when the hibernating bears would wake up and Mother Nature was ready to start a new cycle. The deep winter months in the Rocky Mountains remained empty of humans until the early homesteaders and pioneers built homes on top of the Ute summer sites. The Spanish saw the land of the Utes was full of resources that they valued such as wild game, timber, and fresh water. Because of the harsh weather conditions, rough terrain, and Ute occupation, white settlers did not arrive until 1860 when Joel Estes stumbled on the valley while hunting for a gold deposit. He “claimed” the land by squatting and building two cabins that he and his family used year round. Later he brought up a herd of cattle that had to be watched and guarded constantly from indigenous hunting groups and predators. The ground froze solid in the upper elevations and the cattle had to be brought in close to the cabins to protect them from winter storms and mountain lions. Estes made a small fortune by selling wild game meat in the winter months. He would haul as much meat as he could down the mountain and sell it to the hungry miners prospecting at the base of the mountains in Denver and Golden. Most of the farming work was accomplished in the short summer months and the fall. Hay had to be grown in abundance and stored to last the cattle through the winter. The Estes family relied on stored food, dried meat, and salted fish. The demand was so high for meat that a writing by Milton Estes, Joel's son, reported that he personally shot and killed one hundred elk during a summer and fall season to sell. The trip down to Denver would take four days and then another four back laden with provisions. By the winter of 1864-1865 the weather and living conditions were so severe that the Estes family decided to leave. That winter, Milton Estes described how the snow started in late November and did not thaw until spring. They had to dig through two feet of snow to reach grass to feed the cattle. That year they had to move the cattle down the mountain to save the herd from starvation. Joel sold his claim for a yolk of oxen to a man named Buck in 1866 and in April, the family left, never to return. They settled in southern Colorado and established a ranch where the weather was milder and there was more room for the cattle. News of the Estes family’s valley and beautiful mountain meadows reached other homesteaders and ranchers. Using the trails established by the Ute and other indigenous people, pioneers started ranches, homesteads, farms and timber camps. Once silver and important minerals were found in the Rockies, more mining camps and quarries were established. Lord Dunraven was the first to enthusiastically enter what was now named Estes Park to hunt and attempt to own land for recreation. Winter enthusiasts and mountaineers streamed to the area to enjoy what was described by Lord Dunraven as “long spells of good winter weather interrupted by frequent storms.” Despite the frigid temperatures, intense storms and harsh terrain, pioneers and homesteaders made time for the holidays. Abner Sprague, later to be a land owner himself in what is today Moraine Park, spent two days hiking high into the mountains with a friend to obtain a Christmas tree. The tree was brought back to the community hall in a wagon filled with hay. They put presents that had been obtained in Denver and stashed for months around the tree for Christmas. In Grand Lake in 1883 the Fairview House hosted a New Year’s Eve party. Everyone in the community was invited and a horse-drawn sleigh was sent out to gather anyone who couldn't otherwise make the trek. They enjoyed a large dinner that started at 10 pm and ended with a toast at midnight. Dancing was a popular holiday pastime that people looked forward to it all year. That night they danced until dawn when it was safe to travel again. “The party opened and closed with all joining hands and dancing around the central Christmas tree.” (Grand Lake in the Olden Days, pg 169) Today there are nearly six thousand year-round residents that enjoy winter in Estes Park. Visitors come to Rocky in the winter to snowshoe, hike, and backcountry ski - some of the same activities the pioneers and early native people did. To find out more about native Colorado people and early pioneers, consult these excellent resources: Estes Park a Quick History, Kenneth Jessen, 1996 The Utes, the Mountain People, Jan Pettit, 1990 My pioneer Life, Abner E Sprague, 1999 Early Estes Park Narratives, Milton Estes, 2005 Grand Lake in the Olden Days, Mary Lions Cairns, 1971 https://www.southernute-nsn.gov/history/ute-creation- story/ https://utahindians.org/archives/ute/earlyPeoples.html  Hillary Eichinger was born and raised in Oregon. She received a bachelor's degree in history and a master's degree in museum studies. she has worked with artists in gallery and museum projects for over 20 years. She is passionate about art, history, photography and natural preservation. This piece of independent and local journalism was made possible by Snowy Peaks Winery and MacDonald Bookshop/Inkwell & Brew.

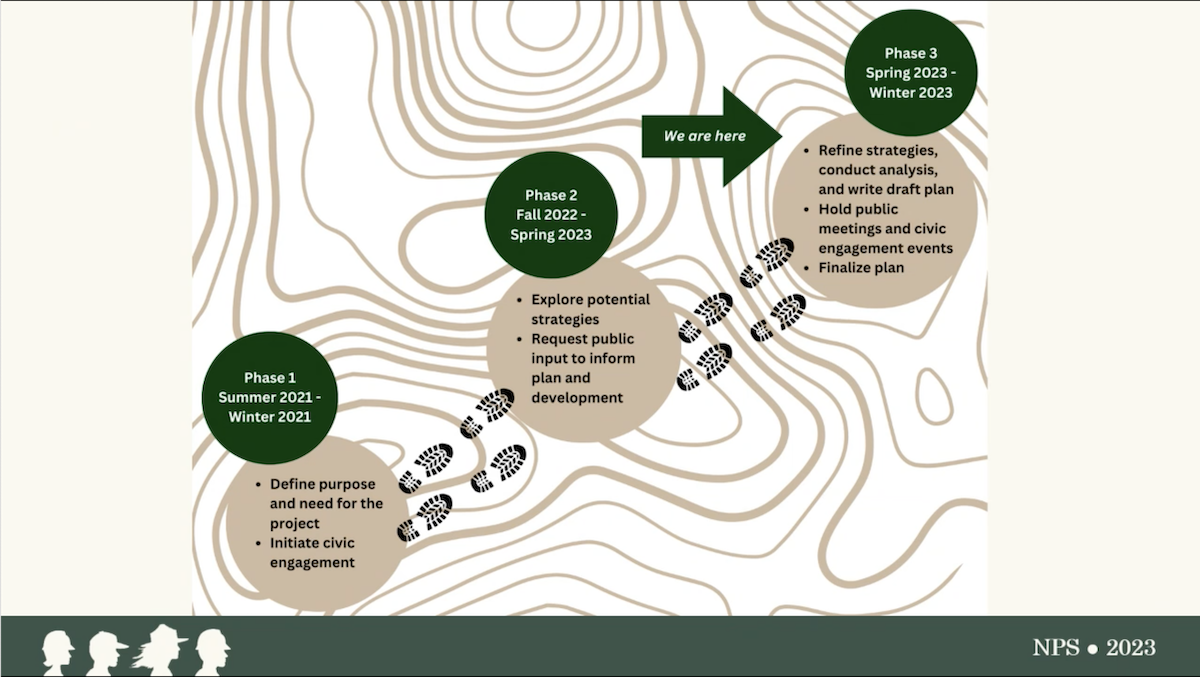

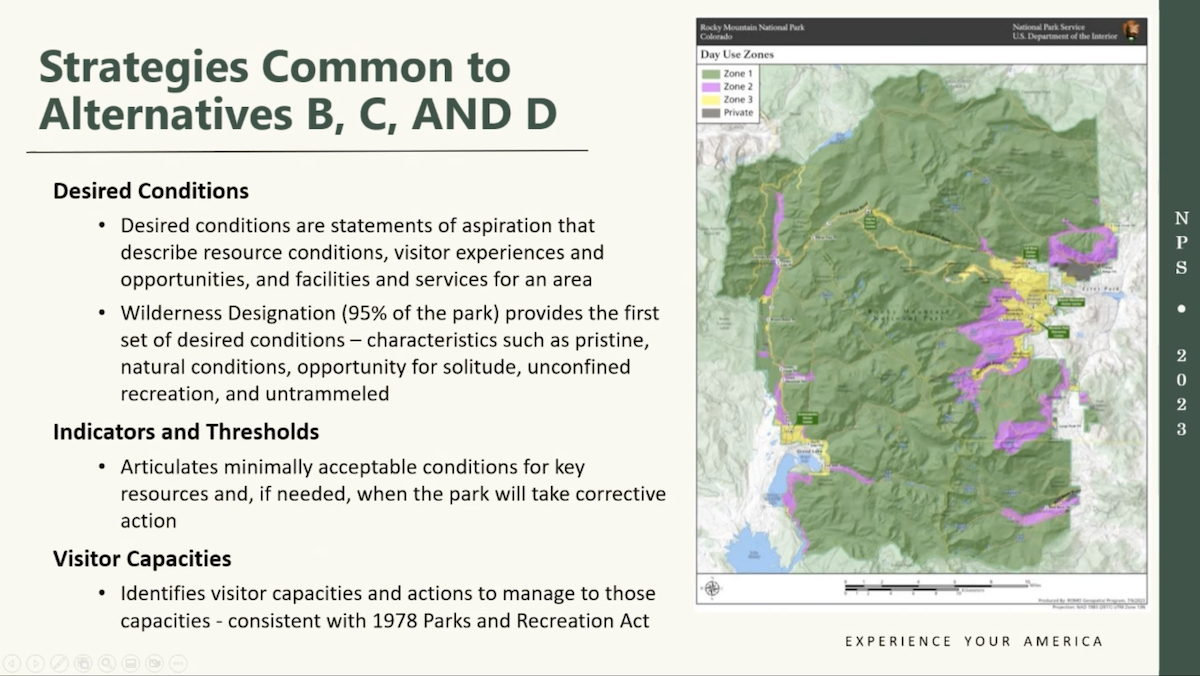

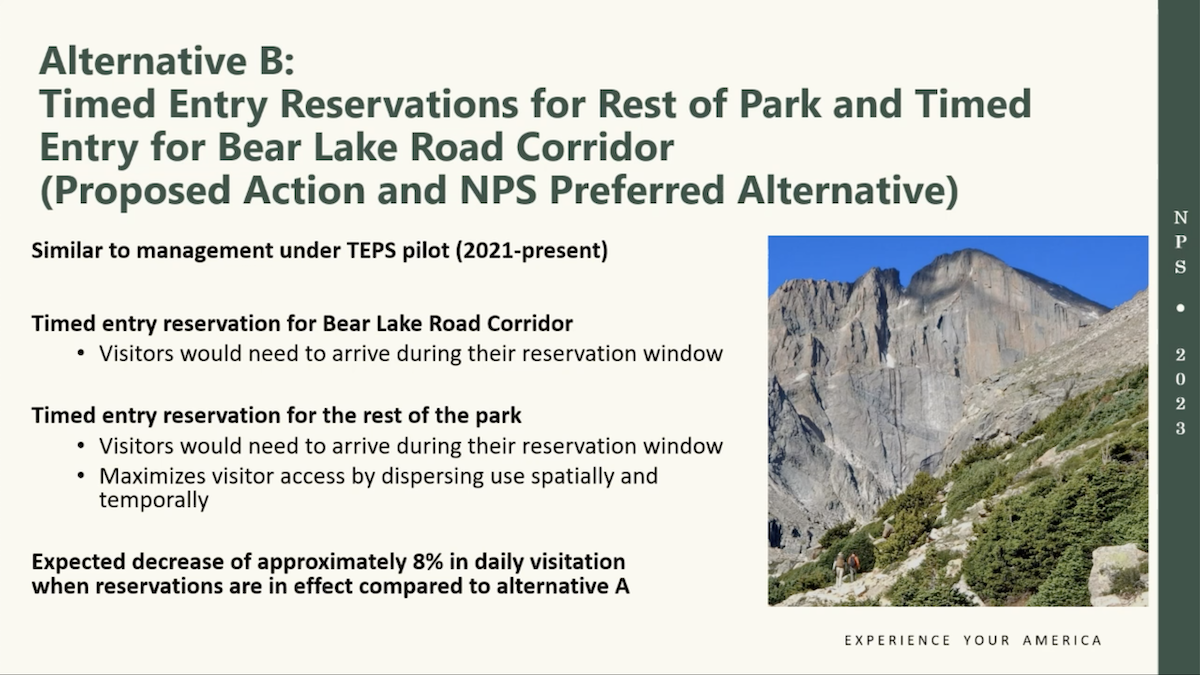

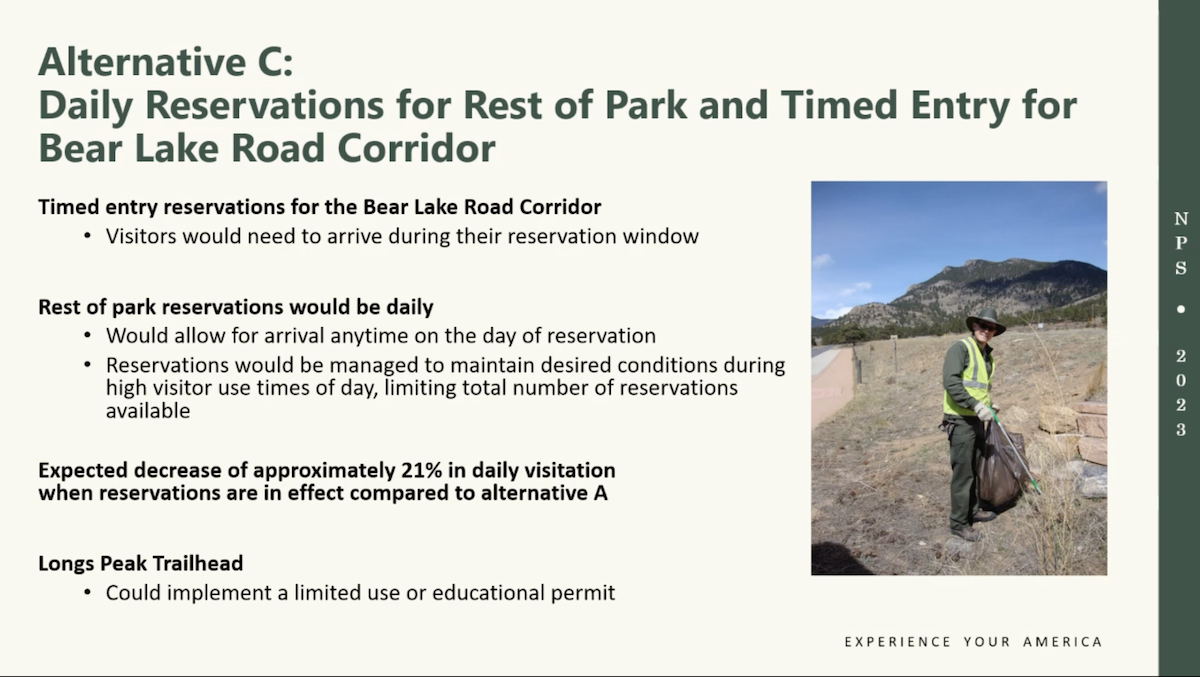

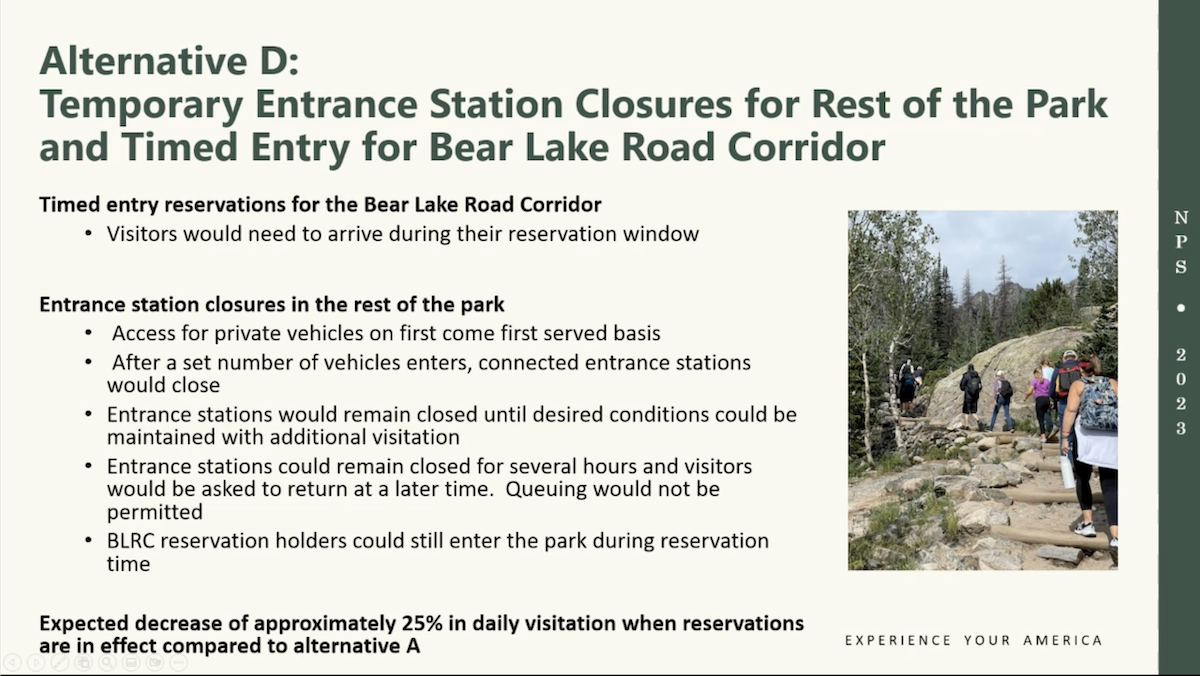

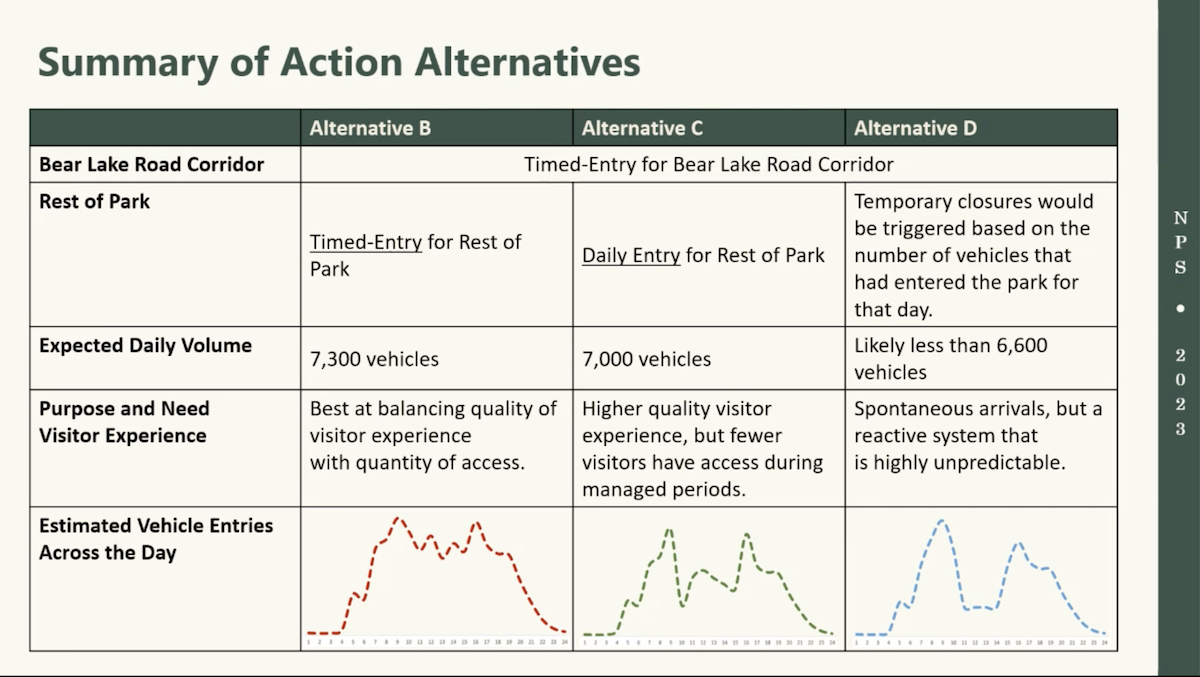

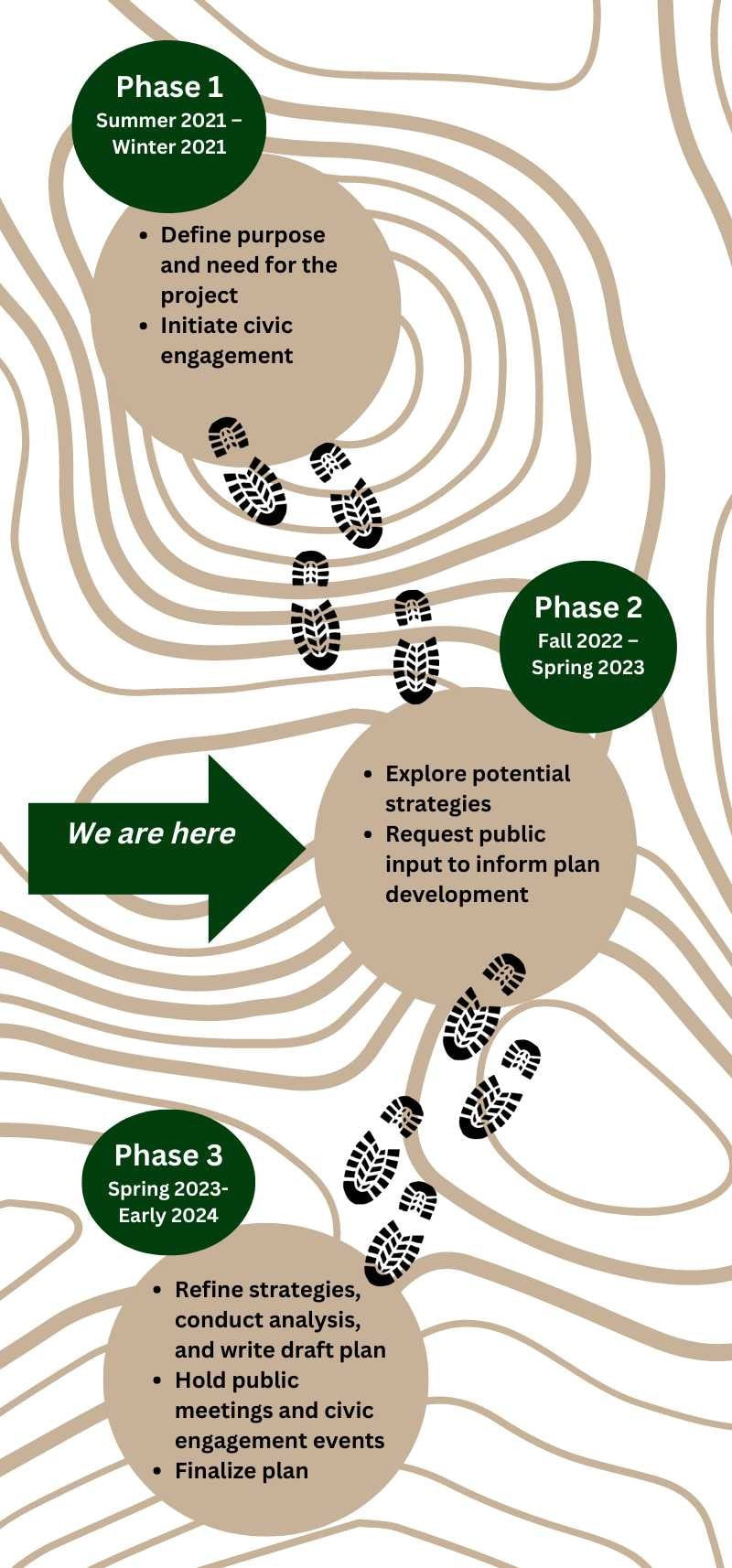

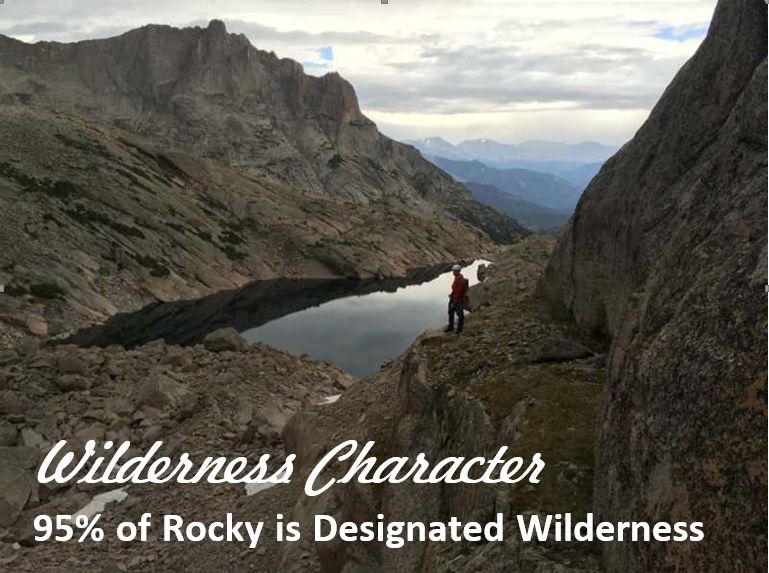

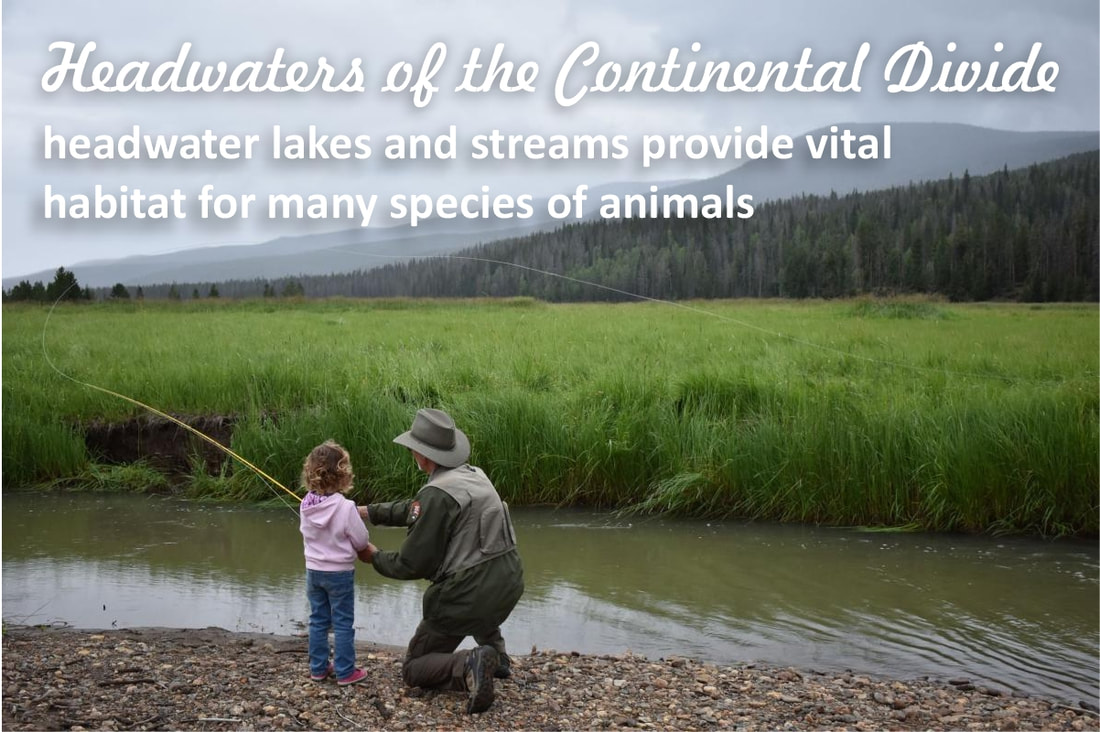

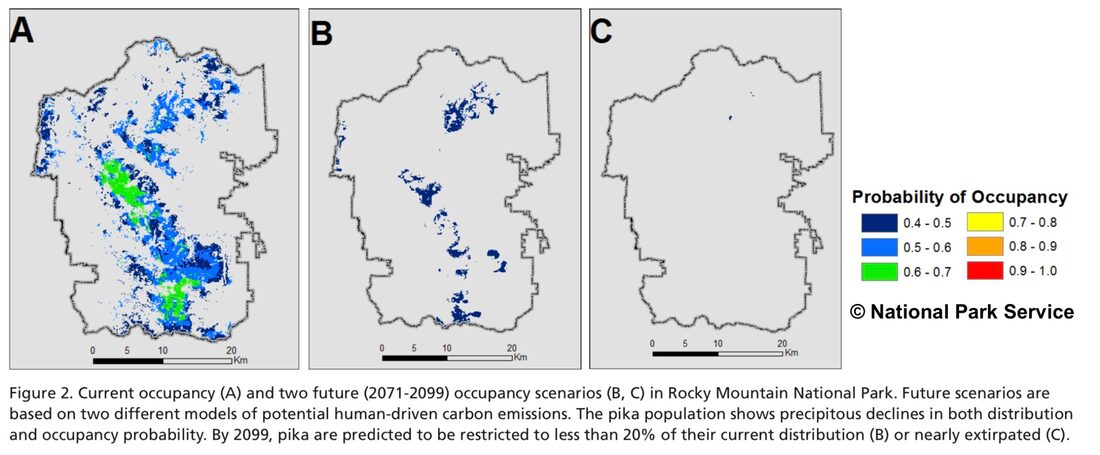

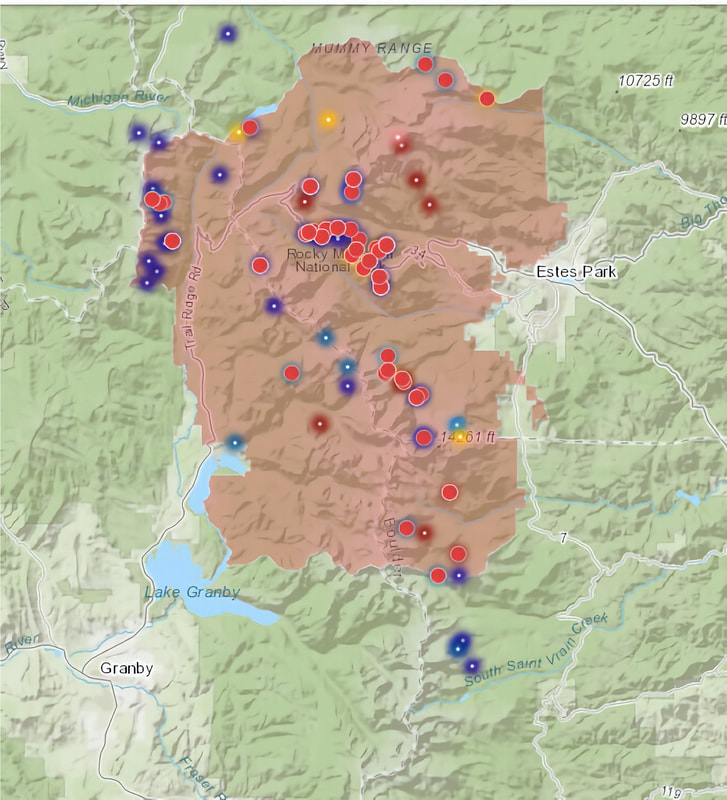

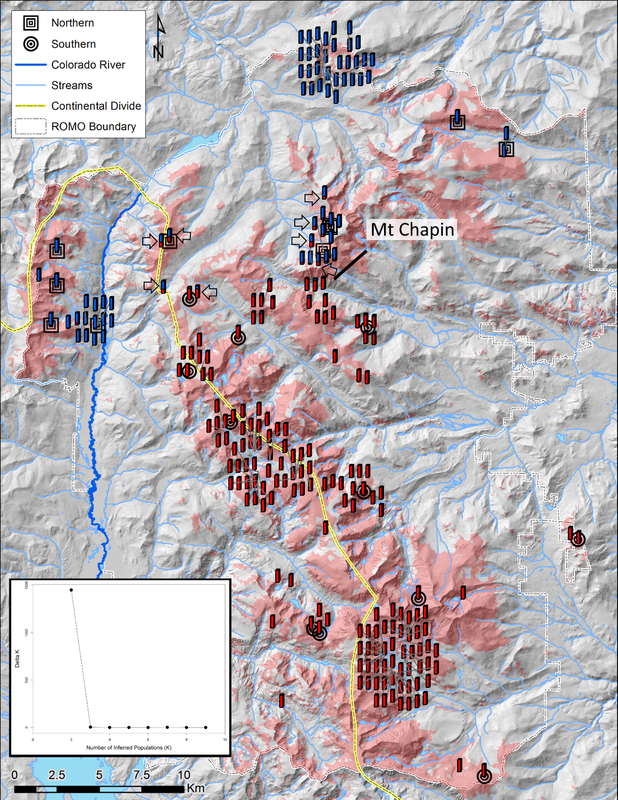

by Barb Boyer Buck, HIKE ROCKY's managing editor All photos courtesy of NPS/ROMO Yep, it's coming back. Another pilot timed-entry reservation system (with slight tweaks over the 2022 system) will start on May 26 and extend through October 22, 2023. Day use visitor management in Rocky Mountain National Park is not going away; it actually started in the late 1970s, when a shuttle system was first implemented in the Bear Lake Corridor and has continued ever since with increasing restrictions on congested areas of the Park during peak visitation times. “From 2016-2019 it was really a very reactive stance: when those areas became highly congested and there were significant impacts, we started closing those areas and turning visitors around,” said Kyle Patterson, RMNP’s Public Information Officer, in a public meeting on December 15, 2022. “As we moved through the years, we saw that we needed to do that on more days. So, in 2019 in July and every weekend June-September we were turning people around daily.” Rocky is now taking a proactive approach to visitor management and is in the public input stage of developing a long-term solution. The Park needs help: your input on proposed ideas and suggestions on how to improve them will be taken until February 1, 2023. Timed-entry reservations have been required during the Park's peak season (Memorial Day weekend through mid- to late-October) since 2020. Some of the social media scuttlebutt attributed the first year's implementation to COVID or a way for the Park to make more money, but neither is true. The first three years of the timed-entry programs (TEPS) have been stopgaps to handle the explosion of visitors, especially in 2019 when the Park's visitation reached a record 4.6 million, a 44% increase since 2012. But more needs to be done. “Even after implementing the timed-entry system, in 2021 we saw our second- highest visitation with 4.4 million people,” said RMNP Superintendent Darla Sidles at the Dec. 15 virtual meeting. People love Rocky Mountain National Park and they are not going to stop coming. So, the Park needs to find ways to fulfil their mission under the Organic Act, which defines the mission of National Parks; and, the Wilderness Act, under which 95% of Rocky was designated wilderness in 2009. These two laws limit the Park's ability to build new infrastructure such as adding new parking lots or widening roads, but they also dictate that visitors be allowed to recreate on this public land. “It's a balancing act that we all focus on every day at Rocky Mountain National Park with our efforts to conserve park resources but also to provide for the amusement and enjoyment of not only all of us right now, but to provide for future generations,” said Patterson. The first public outreach in the process of developing a long-term visitor use program occurred from Spring 2021-Winter, 2021 (Phase One), during which the plan's purpose and need for the project began and civic engagement was initiated. NPS is now in Phase Two of the process where potential strategies are being explored and public input on several preliminary strategies is requested. Phase Three of the project begins in the Spring of 2023 and will continue through winter of that year; a "permanent" solution is scheduled to go into effect in 2024. John Hannon, Rocky's Management Specialist - Business Programs, presented four strategies along with additional complimentary strategies that could be combined to derive a permanent solution. Idea One looks very similar to what we've been experiencing for the past couple of years. It includes two separate timed-entry reservation programs for private vehicles, made available from an online vendor (the $2 reservation fee does not go to the Park, it's the vendor fee for providing the service). These reservations could be ticketed or distributed through a lottery, or a combination of both. Each reservation would have a two-hour window for arrival, with no limitation on length of stay. Some of the reservations would be held back and released for sale the night before. Unlike the pilot TEPS, Idea One may include a commercial-use strategy. Those impacted by this would include chartered buses and tours. The benefits of this idea include the ability of visitors of plan their trips to Rocky, an increase in the quality of the visitor experience, and the opportunity to visit the entire Park under one reservation. The trade-offs include an additional charge (the $2 reservation fee) and the need for internet service. The number of reservations would likely decrease, Hannon said. There was a decrease in reservations in 2022, reported Patterson on Dec. 15. “In 2022, some days we still had some reservations left,” she said. This could be from a variety of factors, she speculated. “Gas prices probably had an effect, but 30-40% percent of our visitors come from the Front Range, so perhaps it was not a big impact. It could be COVID and inflation as well.” Patterson reported that speaking to gateway communities such as Estes Park and Grand Lake, she heard that short-term lodging bookings increased this year, but long-term bookings were down. She also acknowledged that there was a blip in increased visitation before and after the reservations took effect each day. Idea Two includes a set number of timed-entry reservations for each entrance station and shuttle-only access to Bear Lake, Glacier Basin, and Bierstadt. The shuttle would be first- come, first-served during set hours. Entrance station timed-entry reservations would still be booked through an online vendor with a two-hour arrival time window. There wouldn't be any length-of-stay exit requirement and like Idea One, a percentage of reservations would be held for sale the day before and a commercial use strategy may be needed. Pros for this strategy are similar to Idea One, but it more proactively distributes use. Cons are the same, too, but also include having multiple reservation areas. For example, if you got a reservation for Wild Basin, you can't then decide you want to go to Bear Lake and vice versa. Idea Three takes a different approach. With this strategy, you would obtain a daily reservation and can enter the Park any time during that day. There would be a set number of reservations available for each day, made available by ticketing or lottery or a combination of both, and a percentage would be held back to be made available the night before. This idea may also incorporate commercial uses. This idea would likely decrease the number of daily reservations, but would have the added benefit of having only one reservation area and bring more spontaneity to the daily trip. Idea Four gets rid of reservations altogether, but incorporates metering at the Park's entrance stations. This would be similar to the strategy of turning people away from full parking lots within the Park, but it would mean visitors would be turned away from even entering when parking lots are full. If you get in line to enter the Park, temporary delays of three to five hours could be expected. The benefits would be no additional fees, no internet needed, and no reservations required. One trade-off includes traffic possibly being backed up into Estes Park and Grand Lake, blocking private and public access. In addition, once inside the Park, visitors may be blocked from desired locations when the lots fill during their stay In addition, area-specific strategies could be combined with any of these ideas, said Hannon. At Longs Peak, you may need to get a permit before climbing to the summit. “This gives us a way to educate people about the dangers and make sure they are prepared for the climb,” said Hannon. Longs Peak is Colorado's deadliest mountain, reporting more than 70 deaths since Rocky was established in 1915. This also means that Rocky's Search and Rescue operations are among the busiest of the National Parks. There's only one, narrow, dirt road to access the Wild Basin parking area which, like many parking lots in Rocky, are small and fill quickly. Illegal roadside parking not only blocks traffic, but has a significant impact on the surrounding environment. The fire danger increases with this type of activity when there are extremely dry conditions and hot exhaust pipes meet brittle grasses. Wild Basin-specific regulations on vehicles could be incorporated to any of these ideas. Trail Ridge Road crosses the Continental Divide and is the highest continuous highway (at elevations of more than 12,000 above sea leave in some areas) in the United States. It also slices through some of the most important habitat Rocky preserves: the tundra. Tundra makes up one-third of Rocky Mountain National Park and is extremely fragile. Some of the tundra plants will take hundreds of years to recover if they are trampled on. Key destinations in the tundra ecosystem could be additionally regulated. Expanded shuttle service and enhancing education and trip-planning services are also being considered. A successful strategy must be in the sweet spot of where feasibility, desirability, and an effective strategy meet, said Hannon. “The purpose of the long- range planning really is to help ensure we're protecting the park resources, provide the best experience that we can for our Park visitors, that we are improving our staff and visitor safety, and that we are being commensurate with our operational capacity,” Sidles said. The Park is relatively small, about 265,000 acres, said Sidles. Most of that is Designated Wilderness, which means stronger requirements for land preservation, making sure that any human who visits does not remain for a significant period of time. Bear Lake Road was built in 1929 and Trail Ridge Road in 1932. These roads were narrow, one-lane roads that were built to reach specific destinations. Today, they are popular touring roads, with many vehicles stopping at various pull-out points. The Alpine Visitor Center and parking lot is a problem unto itself, with most travelers stopping there to use the facilities, get more information about the Park, and to visit the Trail Ridge Store & Café – the only current concession area within the Park. We at HIKE ROCKY magazine encourage everyone to take some time thinking about and researching these ideas; and, submitting your comments and suggestions by February 1. You can find Rocky's detailed plan options here, and submit your comments and/or suggestions here.  Barb Boyer Buck is the managing editor of HIKE ROCKY magazine. She is a professional journalist, photographer, editor and playwright. In 2014 and 2015, she wrote and directed two original plays about Estes Park and Rocky Mountain National Park, to honor the Park’s 100th anniversary. Barb lives in Estes Park with her cat, Percy This piece of independent and local journalism was brought to you by Snowy Peaks Winery and XplorerMaps

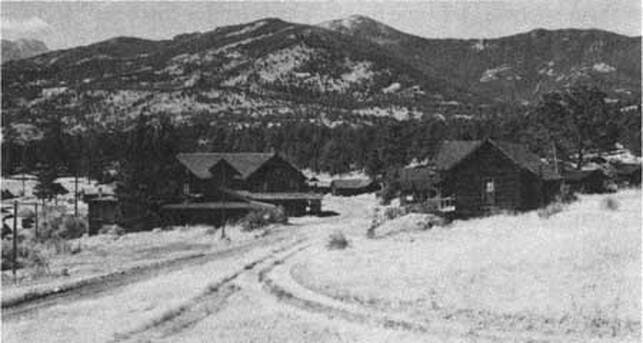

Research & story by Hillary Eichinger Rocky Mountain National Park is not only home to stunning views and amazing wildlife, it also preserves more than 600 buildings. In the 107 years since its inception, the Park has changed shape and size, incorporating natural areas, old mines, irrigation ditches, dams, logging camps, commercial areas like hotels, and original homesteads. National Park Service specialists maintain the integrity and upkeep of its historic places including trailheads, natural areas, and buildings. The area around Estes Park and the Longs Peak area has been a popular destination for tourists, adventurers, and outdoor enthusiasts since the late 1800s. Before the Park was founded, a great deal of the land belonged to the National Forest Service and various private holdings. Many of these holdings were homesteads, ranches, patented mineral mines, timber camps, and stone quarries. These private-owned properties were dotted across some of the Park's most famous destinations including Bear Lake, Horseshoe Park, Moraine Park and the area between Lulu City to Grand Lake. At the time of its founding in 1915, the Park was 229,062 acres, 11,000 of which was inholding property. This included various ranches, farms, mines, and 15 hotels. A great deal of the visitation was capitalized on by building hotels and backcountry lodging.

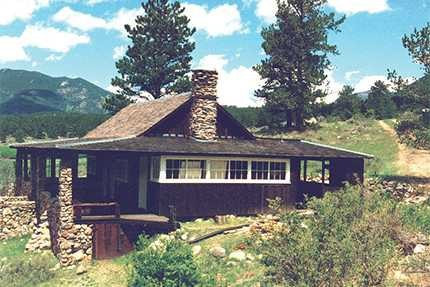

and Hazel Davis who expanded it to accommodate the growing tourist population. The Cascade Lodge, later called Cascade Cottages, was made for tourists coming to the area who wanted to experience the outdoors in a rustic setting. The new owners changed the lodge's design and style to match the growing popularity of the motel motorway. Roads and drive-up cabins soon were soon updated to accommodate motorized visitors. Located along Fall River Road, Cascade Cottages grew in popularity and the accommodations had to be expanded again in 1960. It was owned and operated by three generations of the Davis family, staying open to visitors until 2016. The Park purchased it a year later through combined fundraising efforts by the National Lands Trust, the Rocky Mountain Conservancy, and the National Parks Service. At 43 acres, it was one of the largest privately-owned properties within the Park boundaries. Fourteen buildings of historic significance remain, including some of the original cabins. Some of the ranches took advantage of the vast visitor base and became dude ranches, offering trail rides and overnight accommodations. After selling their homestead near Lake Granby, John and Sophie Holzwarth bought property on the west side of the Colorado River in 1917; 160 acres in the Kawuneeche Valley. A few years later, they increased the family's holdings in size by 900 acres with the addition of the nearby Fleshut Ranch. An original cabin, named 'Mama' by the Holzwarth's, still stands today. The family's original intention for the property was to build a horse and cattle ranch, but when the nearby Fall River Road (which now connects with Trail Ridge Road) opened in 1920, they soon discovered serving the passing motorist tourist industry was more lucrative. They built small cabins on the property and called it the Holzwarth Trout Lodge.  “Mama” cabin on the Holzworth site; courtesy RM Conservancy “Mama” cabin on the Holzworth site; courtesy RM Conservancy In 1923, Holzwarth's son Johnnie established and ran the Fleshut property as a ranch, renaming it Never Summer Ranch. He also built a saw mill in 1924 that served the family's large property and nearby areas. In 1957, there were eight buildings at the ranch and 13 at Trout lodge. In 1975, the Park acquired the combined Holzwarth properties and a year later, the Park's boundaries were expanded to include the area. Never Summer Ranch was listed in the National Register for Historic Districts in 1977. In 2004, the area was renamed the Holzwarth Historic Site and is used for education purposes and open seasonally to the public. Between 1941 and 1951, Rocky's visitor population increased from 663,000 to 1.33 million. This increase caused the Park Service to rethink their buildings and facilities within the Park. The historic buildings within the Park today that are still in working condition have been preserved or converted into functional buildings. Most of these buildings are ranger stations, volunteer housing, and support facilities for the growing number of visitors. By 1966, in a massive undertaking to accommodate for the growing visitor base, Rocky built and opened three new visitor's centers. The Beaver Meadows Visitor Center, Alpine Visitor's Center and the Grand Lake Visitor Center. All three were at the forefront for modern park design by combining shopping, food and preliminary information about RMNP in a central location. The visitor centers also function as the Park's administrative buildings. Today, all three visitor's centers are intact and actively being preserved as part of the Park's long history. Most of the original buildings in the Park that are still standing are considered historic and are on the National Register for Historic Places. One of these buildings, built in 1930, is now being used as the Glacier Basin Campground Ranger Station. The William Allen White cabin, located in Moraine Park has been preserved and updated to accommodate the artists in residency program. White, a newspaper editor, used this cabin as his summer residence from 1912-1944. To qualify for the Register, a building has to contribute historically to our understanding of engineering, archaeology, culture or architecture. The building also has to be over fifty years old and/or be a good example of its time period and the place in which it was built. Park buildings on the Register exemplify pioneer, homesteader, or log- cabin architecture and provide a glimpse into the history before RMNP was founded. As the latest addition to the Park's acquisitions, Cascade Cottages are currently being restored and plans for the area’s development are forthcoming. As of August 27, 2020, the 14 historic buildings of Cascade Cottages and the surrounding 43 acres of property have been included in Registry. The ‘Mama’ cabin in the Holzwarth Historic Site is under restoration by the Rocky Mountain Conservancy as well as is the William Allen White cabin. If you would like to learn more about historic buildings in Rocky Mountain National Park, visit Rocky's administrative history online or stop by any of the Park's visitor centers. If you would like to donate to the preservation of historic buildings or learn more about the ongoing restoration projects visit rmconservancy.org Bibliography Nps.gov administrative history ch 12 Colorado encyclopedia.org Rocky mountain conservancy, projects Rocky mountain national park pictorial history, ]Kenneth Jessen Rocky mountain national park historic places, William B Butler  Hillary Eichinger was born and raised in Oregon. She received a bachelor's degree in history and a master's degree in museum studies and has worked with artists in gallery and museum projects for more than 20 years. She is passionate about art, history, photography and natural preservation. This story of independent and local journalism was made possible by the Rocky Mountain Conservancy and Backbone Adventures.

Story and photos by Chris Reveley for HIKE ROCKY magazine Editor’s note: The Tonahutu Trail was reopened on July 9, but closed again on July 21. This hike was taken on July 13, 2022. October 14, 2020: The East Troublesome Creek Fire was first reported, burning in the hills, northeast of Kremmling, Colorado. Pushed eastward by high winds, the blaze would leave two people dead and consume hundreds of structures in its path. Entering the National Park, the fire quickly burned halfway up the North Inlet valley and through the entire Tonahutu Creek drainage. Reaching tree line and lacking fuel, the fire's aerial acrobatics allowed it to vault over more than a mile of dry, grassy tundra to re-establish itself east of the Continental Divide. High winds continued and Estes Park was evacuated. The flames marched to within two miles of the town's west boundary. The Tonahutu trail starts near the summit of Flattop Mt. and travels northwest across the tundra before descending toward Grand Lake, passing through some the worst of the Park's fire damage. It had been closed to hikers and backcountry campers since the fire; blocked by many fallen trees and threatened by the still-standing, blackened skeletons of others, the trail was unsafe and impassable. Bridges, signs and hitching rails were destroyed. In July, after almost two years of restoration and rebuilding by determined RMNP trail crews, the Tonahutu trail was reopened to the public. I wanted to see it for myself. The shortest hiking route from the Park's east side to the west is about 15.5 miles and starts at Bear Lake with 4.4 miles up steep, rocky terrain on the Flattop Trail. With a reliable headlamp (and a backup!) I always do the first few miles in the dark, timing my arrival at tree line with the sunrise. Over the last 50 years I've taken scores of photos from this area; sun peeking up over the plains, the monolith of Longs Peak brooding to the south, first light touching the Mummy Range. These views never look exactly the same twice so here I am, taking all the same pictures again! Funny. Just past the Flattop summit there's a choice to make; left on the North Inlet trail or right on the Tonahutu. Both trails wander across tundra for a distance, marked by large rock cairns built up by passers-by over many years. Before long, the Tonahutu begins to descend into the valley it will follow to Grand Lake. As I drop down off the treeless tundra, stunning views down the charred valley are revealed. Suddenly, I arrive at the exact place where the fire became air-born and crossed the tundra to reach the Park's east side. This is what I came to see. All the trees are burned, right up to the point where the trail drops into the former forest. But then, something strange: There are a few small groves of big trees above this spot that somehow survived, sandwiched between the complete destruction that came roaring up the valley and the tundra. What would I have seen, standing to the side as the fire passed? Did the steepening slope and the rising winds cause the firestorm to ascend vertically, going totally atmospheric and missing a few lucky survivors? The next six miles of trail pass through one long graveyard of blackened coniferous hulks, sculpted by flame. Many have been burned almost completely through, leaving me wondering what is keeping them upright? With the first strong wind the trail will likely be covered by burn debris again. Scores of the fallen trees that had blocked the path have been cleanly sawed through and removed by trail crew teams. By the time I reach the Green Mt. trail junction and finish the last couple miles to the parking lot, I've counted at least five newly-constructed bridges, lots of new trail signs and several rebuilt trail segments. I've met Paul, a Park Service employee who is far up the valley, alone, hiking with a large pack. He is surveying backcountry assets, particularly important in the aftermath of the fire. I've stopped to thank the ladies and gentlemen of a trail crew. They look tired. There is nothing particularly glamorous about this work but what they've accomplished is impressive. “We have a lot more to do”, they admit. By the time I arrive at the Green Mt. trailhead, I've taken 70 photos. The blackened forest climbs thousands of feet up the sides of the valley while lush, green undergrowth has returned and covers the low, wet areas. The contrast is startling but hard to capture with my phone's camera. And the damage goes deeper: A Park Service naturalist tells me the fire's extreme high temperatures have sterilized the soil in many places, making any kind of new growth impossible for a long time. Normally, along this traverse of the Park, I would see bighorn sheep, moose, elk and deer. Today, no wildlife at all. Investigations have concluded that the East Troublesome Creek Fire was started by people, not lightning. Was it intentional or accidental? Could those responsible have imagined what the results might be when they started the fire? Here in the bone-dry West, it is probably time to abandon the tradition of a roaring campfire during the dry seasons. Wise management of our natural resources includes education and planning as well as acknowledging our ability to do great harm, accidently or otherwise. How should we respond to those whose neglect or intentional actions damage these fragile terrestrial and atmospheric shells we inhabit? As the species with the greatest intelligence and the greatest negative impact we bear the greatest responsibility. But, again and again, we are failing the Good Stewardship Test. Our relationship with the earth is both loving and abusive, trending more toward the latter as our benign inattention allows environmental disasters to proliferate. It may be that humankind lacks the intelligence, foresight and desire to maintain the planet, happily trading short-term profits for long term survival. If we can't stop poisoning our home, our relatively brief 70-million-year residence on planet Earth will come to a whimpering end, only to be appreciated by other, surviving life forms as a cosmic, not-to-be-repeated experiment in neglect and exploitation. The evidence is in: forest, water and atmosphere are not unlimited resources that will rejuvenate and regenerate faster than we are destroying them. Sadly, environmentalism has become a political issue with a portion of our population denying there's a problem. We elect “leaders” to make wise decisions and, more and more, they are willfully and proudly ignorant, incapable of understanding the issues, much less responding wisely. Again, today, after thousands of adventures of all kinds in RMNP, my passion for the place survives, undiminished. The future of the Park and, indeed, the planet can be bright. It's entirely up to us.  Chris Reveley has spent 50 years climbing and doing endurance sports; and, thirty years learning and practicing medicine. “Now I’m a Happy House Husband with hobbies,” he said. The publication of this piece of independent and local journalism was made possible by Erik Stensland's Images of RMNP and The Country Market, both of Estes Park.