|

story and photos by Jason Miller There is no shortage of wonderful hikes in Rocky Mountain National Park. This month's hike that I am featuring is one that almost anyone can conquer. It does not involve any climbing or bouldering but brings the essence of the Rockies from start to the finish. Today (in early April) is starting out to be a great day. It is around 50 degrees with a low blowing wind coming over the mountains. Sunglasses and coffee in hand, I drove past the Beaver Meadows Visitor Center and onto the entrance to the park. Once arriving at the Beaver Meadows entrance, I knew that I wouldn't see many people out here today. There is no one in line at the gate. I entered the Park and drove past the Beaver Mountain Loop Trailhead and up to Deer Mountain Junction. Across the street from the Deer Mountain Trailhead is a sign and a trail off into a vast meadow peppered with spruce and snow. Beaver Mountain Trailhead Starting down the trail I was quick to notice that there were not many footprints in the snow. People must rarely go on this trail. The walk involved a gentle downhill slope with no snow on most of it and some areas with snowpack. I chose to leave my micro spikes and snowshoes at home this time. I didn't need the micro spikes because the snow packed areas were slushy. This was due to the awesome weather that we have been having as of late. As I was going down the trail, there were signs of elk being here, birds chirping and once again, only a few footprints. I stopped to snap a picture and noticed that there is nothing out here but total silent nature: still, but full of life. Crazy, every time I come to the Park I see or feel something that is new to me. I am blessed to be one of the lucky few to call this place home. TOTAL SILENT NATURE! Just a little farther down I come to a fork in the trail. The sign gives me a little direction of where to go. Right or left. I chose right and went across some grassy spots and snow-covered Beaver Creek. Now there is no trail, no footprints, only snow over a huge meadow. I went for it and tried to continue. Heading toward a group Aspens I realized that snowshoes would have been a great idea. I made it to the trees and took a well- needed rest. Looking up, I see all sorts of evidence of woodpeckers: numerous holes in the large Aspen trees. This is a woodpecker condominium. There are multiple holes that have been created by these awesome, sometimes annoying birds. I tried t go a little farther up the meadow and it proved t be more than I wanted to deal with. I was sinking up to my knees in the snow, I turned around and headed back to the trees again. went onward to the sign that put me in this direction. OK, now let's go the other way. I walk about five minutes and came upon the same scenario. Snow with no path or footprints to be found. Sinking to the knees. NO THANK YOU! I really should have brought my snowshoes. I turned around again and headed back toward the parking lot. On the way back to the trailhead, I find myself picking up trash. There have been very few hikers on this trail leading to NO TRASH. Amazing. I stopped a couple more times for more photos. After making it back to the parking lot I checked my time. This only took 1.5 hours. I was planning a little longer but without snowshoes …no go! Having some extra time, I decided to pick up trash. Starting at the parking lot I was in and continuing to all designated areas around Deer Junction. It is incredible the amount of trash that is left behind. I left there and decided to clean up every pull-off area on my way out of the park. One by one, I drove to admiring the views that RMNP has to offer. At the pull-offs there are socks, masks, bottles, cigarettes, cans, and metal. All of us stop and take pictures at these spots but it is dirty. I challenge you. Yes, YOU! Do not leave Rocky the same as when you got here. Leave it better. Go out of your way to look for and pick up trash all along the way on your future hikes. Only you and I will lead the way to a cleaner and more natural park. This one picture shows just a sample of what is out there in our beautiful Park: hazardous to the animals and detrimental to the landscape. I have tagged this photo on social media to show what is out there and what we can do. #keepourparkclean  Jason Miller, 49, is a resident of Glen Haven and is married with two children. Before moving to the area, he used to work as broker for Nestle USA and H.P. Hood milk company. Today, he is the owner of The Rustic Acre (vacation rentals in Estes Park) and co-owner of Lightbrush Projections.

1 Comment

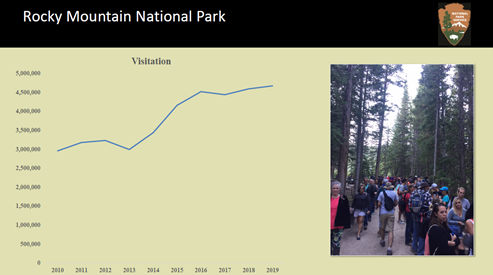

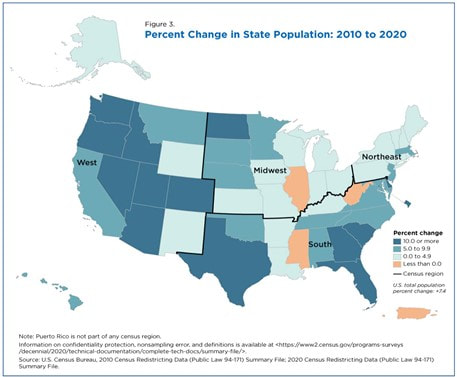

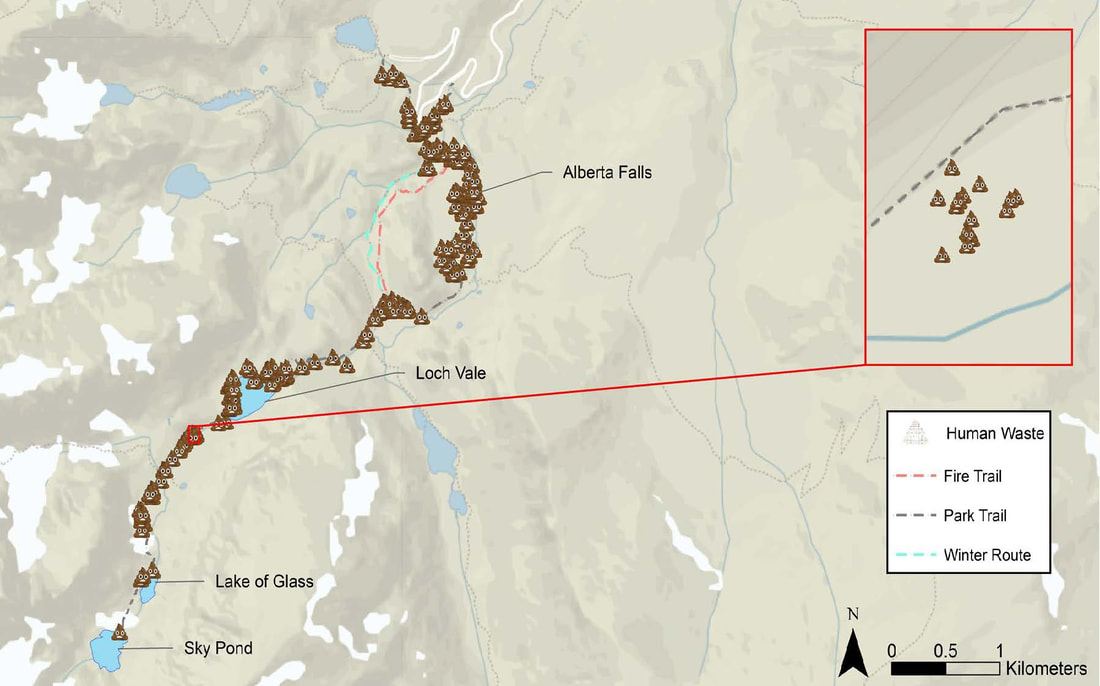

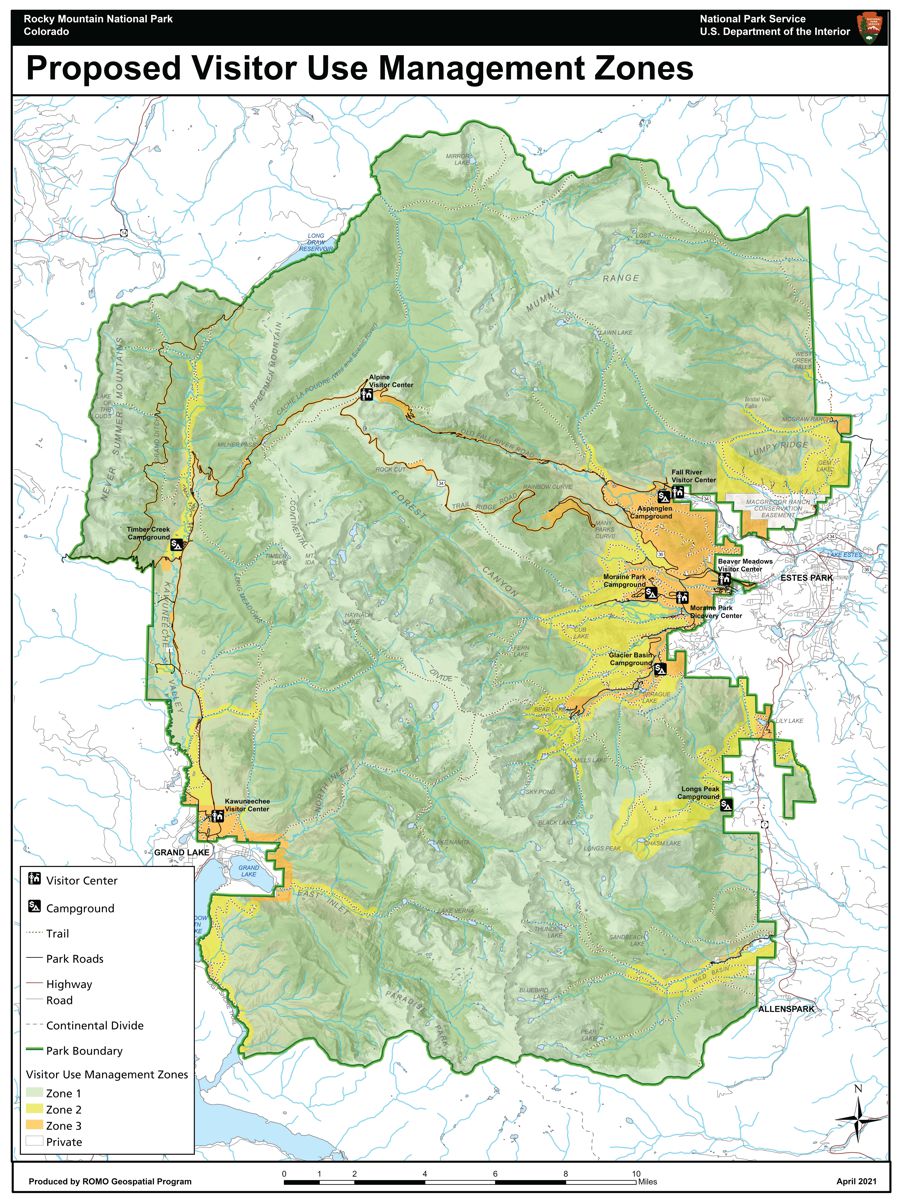

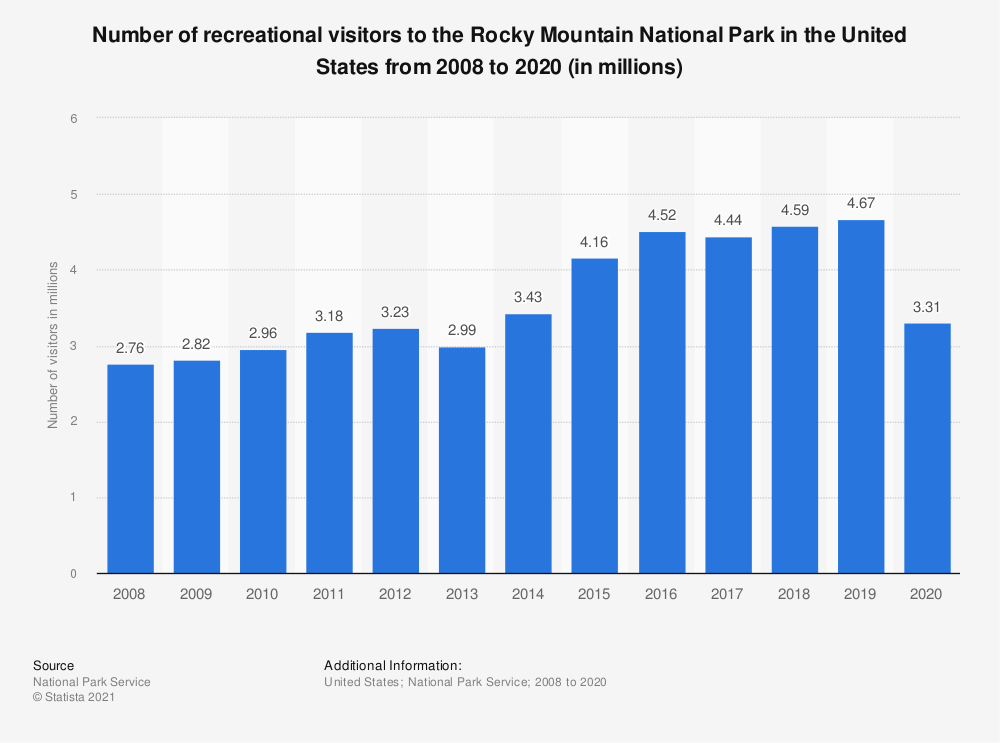

editor's note: this story is pulled out in its entirety from the February/March edition of HIKE ROCKY digital magazine. For more information about the magazine visit this page by Barb Boyer Buck It's an emergency, calling for emergency measures. The exploding visitation numbers at Rocky Mountain National Park combined with a budget that has stayed flat for a decade has put Rocky's management officials in a defensive position. Something must be done to keep Rocky from being loved to death. “I'd like to say our staffing levels have kept up with the increase in visitation, but it has not,” said Kyle Patterson during a question-and- answer period after a public presentation held on May 25, 2021. This meeting was part of public outreach about long-range visitation strategies in Rocky. “Our base budget that we get from Congress has seen a very flat situation over the past 10 years,” said Rocky's superintendent Darla Sidles at that same meeting. “This flat is essentially an erosion of our budget,” about 14% over that time. Staffing has decreased by 16% as well, while visitation has increased by more than 40% since 2012. Visitation management measures have been in place since 2016 – everything from limiting traffic along the Bear Lake corridor to increased shuttles have been tried to help with the congestion, traffic, inability to find parking, and more. But it wasn't enough; in 2019, the Park's visitation numbers of 4.6 million made it the third most-visited national park in the nation. The following year was a tough one for everyone, but especially for Rocky. The Park was closed for two months between March-May, 2020 due to COVID19, and devastating fires burned more than 30,000 acres (the most in any fire season in the Park's history) from August-October, with dynamic closures of much of the most popular areas of Rocky It was also the first year of timed-entry reservations, a measure that has received a considerable amount of blow-back from the public, especially from those who live near Rocky and along the Front Range. But still, visitation numbers for the year dropped by only 29%, or to 3.3 million visitors. In fact, record-setting visitation occurred in November and December of that year, after most of the Park reopened post-fires and the timed-entry reservation system expired for the season. In 2021, the timed-entry reservation system was modified to address the inadequacies of the previous year's program. Reservations were now required from 5 a.m. to 6 p.m. in the most popular area of Rocky: the Bear Lake Corridor, which includes Bear Lake, Glacier Gorge, Spruce Lake, and Moraine Park and the rest of the Park had reservations-only in place between 9 a.m. – 3 p.m. Even so, visitation for 2021 jumped back up to 4.4 million. The reservation system for 2022 will look a lot like last year's, but it's still considered a pilot program; tweaks were made to address some of the shortfalls of the system that ran in 2021. Reservations will be required from May 27 – October 10, 20, with the first reservations taken on May 2 for May & June dates. “Initially, 25 to 30 percent of permits will be held and available for purchase the day prior at 5 p.m. through recreation.gov. These are expected to sell out quickly and visitors are encouraged to plan ahead when possible,” states Rocky's website. So, those are the nuts and bolts. Not enough funding to improve infrastructure and keep staffing levels where they need to be to properly manage visitation is why we are facing another year of timed-entry reservations. For those of us who live near Rocky and have traditionally been able to pop into the Park when the whim hits us, this can be a hard pill to swallow. The presentation I referred to above fielded questions and collected comments as part of this process; the name- redacted comments are available to read here. They run the gamut from criticizing a lack of privilege for local and Front Range residents to pleas for conserving Rocky's natural wilderness & implementing even more strategies. Some accuse the NPS of a money-making scheme; some say that low-income people will be deterred from visiting. As stated by its Organic Act in 1916, National Park Service's mission is “ to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wildlife therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations." Rocky became a National Park in 1915, but perhaps even more significantly, 95% of its land became designated wilderness in 1974, under the Wilderness Act. Designated wilderness by law meant "...in contrast with those areas where man and his own works dominate the landscape, (wilderness) is hereby recognized as an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain." Why has visitation increased so dramatically at Rocky? The increase in visitation, especially over the past few years, has a direct correlation to several factors. When the pandemic closed off much of the other recreational opportunities available to society, the great outdoors became very popular. This trend pushed those who may have never really visited the outdoors to try it out, which can bring its own problems. Rocky is not at all a “park” like those in urban or suburban areas. Most of it is true wilderness, remote with challenging terrain for even the most experienced outdoorsperson. For example, Rocky has spent an inordinate amount of time pulling vehicles out of ditches this season because the drivers were unfamiliar with driving in winter conditions, or their vehicles were not suitable for the conditions. If the state's traction law is active for Rocky, all vehicles “must have properly rated tires (Mud and Snow, Mountain and Snow or All-Weather Tires) with a minimum of 3/16" tread,” reads Rocky's website on the subject. “If you have improperly rated tires on your vehicle, then you must use an approved traction control device. These may include snow chains, cables, tire/snow socks, or studded tires. When the traction law is in place in RMNP, if a vehicle is involved in a motor vehicle crash, to include sliding off the road due to icy conditions, motorists will be cited if their vehicle does not meet Colorado Traction Control Law requirements.” While overall population growth has stagnated in the US, Colorado's growth has exploded in the past 10 years, gaining nearly 800,000 new residents, leading to another state representative going to Congress. Most of this growth occurred along Colorado's Front Range and Rocky's statistics show that 30-40% of the Park's visitors are from the Front Range. Rocky Mountain National Park's Day Use Strategy Currently, Rocky is working on a long-term day use visitation strategy after its pre-NEPA (National Environmental Policy Act) planning effort and outreach. Additional public comment will be solicited in early 2023 when the formal NEPA process is underway, but the bottom line is that visitor management strategies are here to stay. The pilot programs that have been in place since 2020 will evolve into a permanent strategy based on the results of the NEPA study and other day-use strategies already implemented. Just how restrictive these may be is dependent on funding, staffing, and visitor behavior. The planning process' purpose has many priorities, based on Rocky's mission as a Wilderness Area and a National Park. These include the proper management of the Park's natural and cultural resources, staff and visitor safety, visitor experience, and Rocky's operational capacity. Resource Impacts Social trails, widening of existing trails by visitors, off- trail wandering, and native plant trampling has caused damage to sensitive environments. So has roadside parking, idling, “elk jams” (traffic jams when a wild animal is seen). Vandalism and the illegal collection of artifact damages the cultural sites within Rocky and is “of particular concern to tribal interests.” Human waste has been found in increasing concentrations, affecting water quality and visitor experience. Visitor Experience High traffic congestion at the most popular destinations and roadways has led to frustration among visitors due to the inability to find parking. John Hannon, the Park's visitor use management specialist, reported escalating conflict, including fist fights among visitors and staff, during these times. This congestion has led to the elimination of some popular ranger-led interpretive programs and has impaired emergency response and maintenance of facilities. Even volunteer rangers, desperately needed to help with staffing issues, can't find parking in the places they are needed most. Staff and Visitor Safety Along with physical altercations between frustrated visitors and staff, other safety concerns include visitors illegally starting campfires, approaching, or feeding wildlife, and/or bringing dogs (which are predators to many species) on Rocky's trails. All of these can cause emergency situations that can result in severe injury or death.  Long lines at restrooms prevent staff from properly maintaining these facilities. RMNP photo Long lines at restrooms prevent staff from properly maintaining these facilities. RMNP photo Park Operations and Facilities Higher visitation results in excessive wear and tear on facilities causing the need to triage repairs and focus on the most heavily used areas of the park causing other areas of the park to degrade further. Long lines to get to job sites for facilities, law enforcement, and interpretation staff hampers the park's abilities to provide critical services like maintaining restrooms, responding to emergencies, providing in person program and outreach. Higher water use and wastewater generation than systems can support causes increased frequency and costs of sewage pumping at park-wide vault toilets. Proposed Visitor Use Zones and the desired outcomes of visitor-use strategies In this pre-NEPA process, Rocky Mountain National Park identified three visitor-use zones, each of which are likely to have different visitor-use strategies. Zone One is comprised of 100% wilderness and considered low-use, low-encounter. This area is indicated in green on the map. In this zone is where the natural landscapes are emphasized to their greatest extent. These areas are minimally maintained and provide the best opportunities for solitude and self- reliance. The desired outcome for visitor use strategies in this zone is to keep wilderness conditions pristine, that plant and animal life will thrive with high water quality and minimal human influence and social trails become non-existent. Zone Two provides easy to moderate access to wilderness through Rocky's trail system. These areas are indicated in yellow on the map. and include well- maintained trails closer to restroom facilities, but still provide opportunities to experience the wilderness in relative quiet. The desired outcome in these areas is to keep wilderness recreation plentiful with sustainable trail maintenance and moderately available, well- maintained restroom facilities while retaining the natural integrity of ecosystems, wildlife habitats, and migration behaviors. Indicated in orange on the map is Zone Three, where the most human impact occurs. Envisioned for this zone is that surfaces are hardened or paved to reduce impact on the natural environment and visitors have the most access to information to help them recreate in Rocky and travel with ease to their preferred destinations via private vehicle or alternative transportation. Interpretive and educational programs provide opportunities for visitors to increase understanding and appreciation for park landscapes and resources. The pace of visitation is at a level where park staff can interact with visitors to ensure that visitors are informed, prepared, and use best safety practices. With proper management in this zone, established trails do not exceed design specifications, and visitor- created trails and trail widening are minimal to nonexistent. Visitors experience clean and accessible public facilities, and park staff can access facilities and work areas in a timely manner due to less roadway congestion. Right now, Rocky is still collecting data – the indicators, thresholds, and capacity of the various routes and destinations within its boundaries. In early 2023, the NEPA process will begin, which will give people another opportunity to voice their concerns and make suggestions. Preliminary long-term strategies that are being considered could include a combination of:

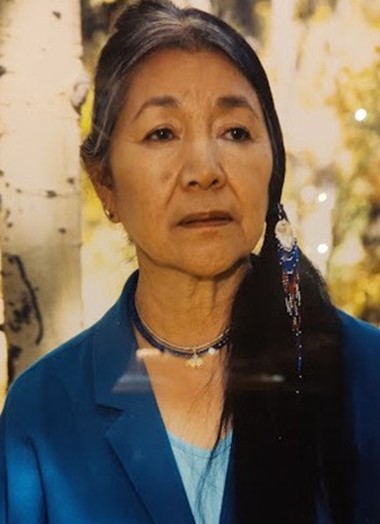

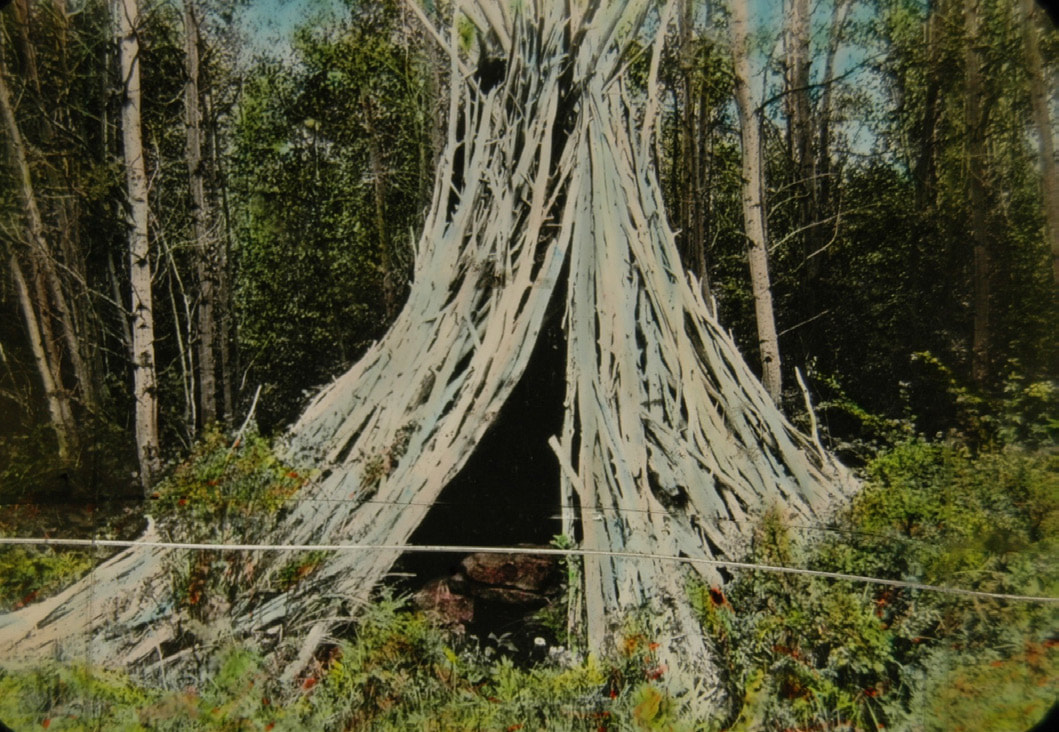

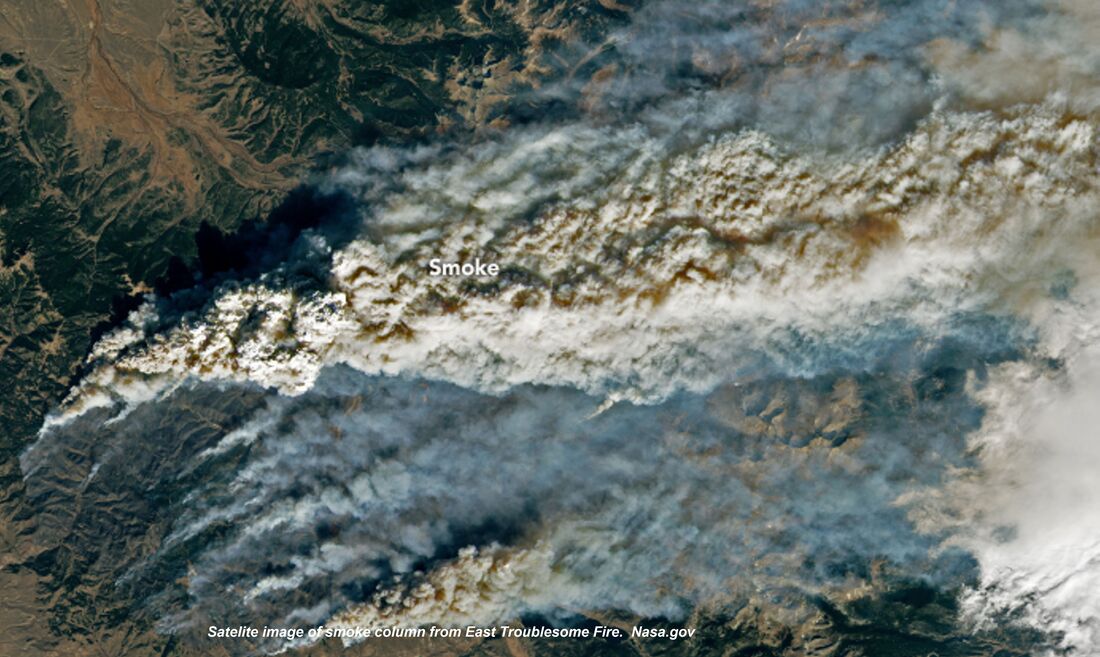

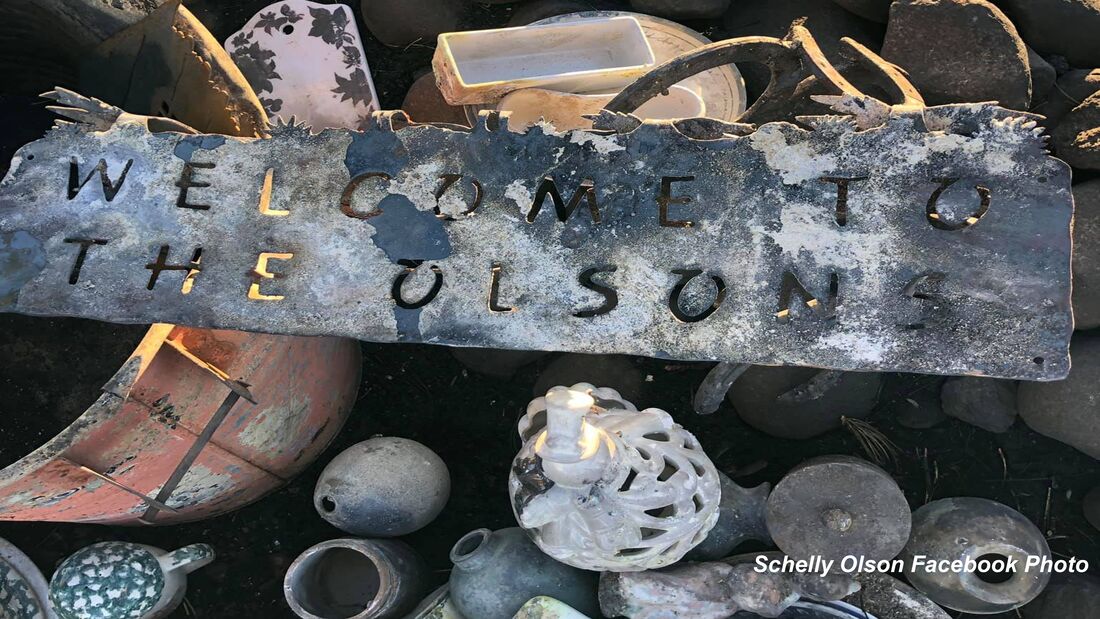

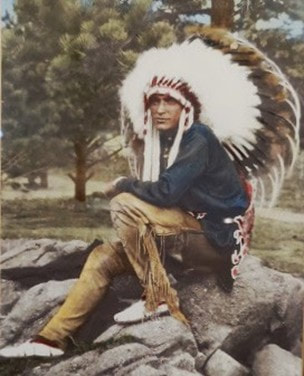

“It's not the Rocky Mountain National Park of the 1970s or even the 90s, unfortunately,” Superintendent Sidle said. “We've been trying some different things over the past six years for how to manage this increase in visitation”, and the timed-entry reservation pilot programs have been a stopgap measure to try to spread out visitation throughout the day. Increased visitation is a nationwide problem; visitor-use strategies are being implemented in several national parks across the nation this year including Acadia, Arches, Haleakala, Glacier, Rocky, Shenandoah, and Zion. “Rocky Mountain is a national park,” said Patterson. “And while so many of us are fortunate to live on its doorstep or moved here because of the Park, we cannot provide special access to locals.”  Barb Boyer Buck is the managing editor of HIKE ROCKY magazine. She is a professional journalist, photographer, editor and playwright. In 2014 and 2015, she wrote and directed two original plays about Estes Park and Rocky Mountain National Park, to honor the Park’s 100th anniversary. Barb lives in Estes Park with her cat, Percy. One Northern Cheyenne woman's perspective on life by Barb Boyer Buck Just a few minutes south of Estes Park, there is a remarkable place redolent with various traditions and history, both native and non-native. Eagle Plume's Trading Post, just over the Boulder County line on Highway 7, is owned by Nico Strange Owl, who took over the full operation after the recent deaths of her parents. Her father, Dayton Raben, passed last December of a stroke and her mother, Ann Strange Owl, lost her battle with Alzheimer's in July. Nico sat down with me last week to speak about the history of the place and her perspective on the traditions which formed her life. To'tseha (The History of of Eagle Plumes) The building itself was built in 1917. It was originally commissioned to look like a Kansas farmhouse by Katherine Lindsay who wanted to open an inn in the proposed town of Hewes-Kirkwood, slated to be developed in the area. Lindsay was an artist and painter in an early art-deco style; she opened the What Not Inn and decorated the establishment with her artwork and beadwork her father “collected” during in the Indian Wars in Kansas. The building next store was the grocery store.  Intricate beadwork is part of Eagle Plume's collection. Intricate beadwork is part of Eagle Plume's collection. After a few years, she realized there was not going to be a town; business was very seasonal and most people were heading to Estes Park or into the national park itself for their lodging needs. She had married a man named Perkins and they turned the inn into a trading post dealing in Native American art from the early to mid-1920s. Her husband was sickly and passed away soon after, so she hired Charles Eagle Plume in the mid-1930s. “He showed up on horseback one day,” said Nico, “and claimed to be one-quarter Blackfoot Indian from Montana. “He was a master marketer; he ran the place and made it famous. He would dress up in Native American regalia and pretend to shoot arrows at the passing cars and then point them toward the store.” Works purchased from Mrs. Perkins and Charles are housed in museum collections, including the Denver Art Museum.  Charles Eagle Plume as a young man Charles Eagle Plume as a young man “Together Charles and Mrs. Perkins built on their collection; they were close, he became like a son,” Nico said. “When she passed away in 1966, she left the store to Charles.” He was adamant about carrying only Native American-made art and goods. This holds true today, except for a line that is designed by Native Americans and made elsewhere. “In the beginning, we could find things to offer that were $5-$10, but not anymore. We carry these to be competitive,” Nico explained. Nico's parents moved to northern Colorado in 1966, when Dayton got a job as a history teacher in Berthoud. “When they got married, interracial marriage was illegal in Wyoming. He was a white man of German and Scots descent from that state, and she was a Cheyenne woman, working on the Wind River reservation. He fell in love with her right way; they were married within three months of meeting,” said Nico.  Dayton Raben and Ann Strange Owl Dayton Raben and Ann Strange Owl “When dad took mom to meet his family, some of them tried to buy her off to get the marriage annulled; they were horrified he had married a native woman. When mom introduced him to her family at her home in the Northern Cheyenne Reservation in Montana, some stared right through him as a sign of banishment,” Nico said. On the advice of his father, the couple moved to California where Nico was born. For the sake of the child, they wanted to get closer to family – “but not too close!” Nico said, which precipitated the move to Colorado. There were frequent trips to the reservation where Ann had lived, but she was feeling lonely for other native people in Colorado. She had an aunt who was southern Cheyenne; this woman lived in Denver because of the government's efforts to assimilate Native Americans into larger cities. "They were trying to take them away  Nico Strange Owl Nico Strange Owl from the native language and culture,” Nico said. Ann didn't feel at home with the Denver Indian community, so someone told them to visit Charlie at Eagle Plume's. “Charlie loved mom right away, he loved native people. He asked her to work for him at the trading post,” said Nico. He kept hounding her until she finally said yes in 1979. “They became really good friends and Charlie adopted mom in the native plains tradition.” In native plains tradition, a person can adopt another (even if they are not related by birth) by exchanging gifts, Nico explained. “Charlie gave her a Cheyenne dress with beaded boots; he made posters to sell from a photograph with her in that dress.” While Ann started working for Charlie in the summers, Dayton would come up and sit behind the shop and read books or take walks. Finally, Dayton was persuaded to work in the shop, too. He would regale the male customers with stories about the weapons in the collection while the women shopped, remembered Nico. Nico began working at the shop when she was getting her degree in Anthropology from Colorado State University. She would come up in the summer, sometimes with friends from college, to work (and nap!) in the shop. ”After a hard night out the day before, "We took turns taking naps up there." “When Charles caught us, he got very mad and made us fold the rugs. That was a horrible job,” she said. “Charles didn't have any children, so he created a buy/sell agreement with my parents, the bookkeeper, and the sales lady,” Nico explained. Immediately after Charles’ death in 1992, the bookkeeper and sales lady broke the agreement and put the store up for sale. “That was a horrible summer,” said Nico. “The sales lady was really prejudiced against Indians and Charles would defend my mom against her all the time.” But now he was gone, and two of the three members of agreement were trying to sell the shop. Nico recalls that through the summer, they hadn't really gotten any offers and curiously, the sales lady began declining in health rapidly; she had kyphosis - an exaggerated, forward-rounding of the back. One day, the bookkeeper came in and said she had changed her mind about selling. Why was that? Well, reported Nico, the bookkeeper had a dream where “Charles came to her, and he wasn’t happy” about the proposed sale. In 1993, the other two women were bought out by Nico's parents, who went on to run the store for the next 30 years with Nico's help. “it's funny, because Charles ran the place for 30 years before my parents got it,” Nico recalled, “and Mrs. Perkins ran it for 30 years before she went into a nursing home. “Before Charles passed away, I was packing up the collection at the end of the year to put it in storage while he gave instructions from his wheelchair. He looked at me and said, 'My dear, one day you will have a son and he will run this store.' I have one son but he doesn't want to run the store like it has been, so we'll see if it comes true.” Perhaps Nico has to run it for 30 years first? Nico was very close with her parents, and Charles. Charles helped get Nico her first job after college, at an Indian art gallery in Vail. “There was a couple that had an Indian shop in Vail and came in and asked Charles if they could consign his stuff for the winter (since Eagle Plume's was only open from mid-May to mid- September).” Charles pointed at Nico and said, “she has to be part of the deal. because he knew she wanted to ski. “So I went and managed their gallery and sold his stock so he could replenish for the next summer. It was crazy how much stuff he had.” So Nico skied, mountain biked, and sold Indian art in Vail for the next seven years. Then, she got married and moved to Denver where she put her now-ex through graduate school. After the divorce, Nico came back to run the store with her parents after Charles died. “We ran it for decades, and I miss them so much,” she said, “but I always knew they would go together, they were so close. After my father died, I had to retell my mother multiple times a day that he had passed,” Ann's Alzheimer's was taking control. “Every time, she would cry and mourn, it was terrible.” Finally in March, it sunk in her husband was gone, said Nico, and then Ann deteriorated quickly. “So now, it's just me and Kay (the current sales person), my son, and a few neighbors who come in and help; it's good,” said Nico. -tsėhésevo'ėstanéheve (to live as a Cheyenne) Today, Nico honors her father by telling his stories to people who come into the store and she honors her mother by trying to be a “good Cheyenne woman.” “What does it mean to be a good Cheyenne woman?” I asked her. “Well, I'm not a great Cheyenne woman,” she laughed, “but I try.” A good Cheyenne woman works hard and keeps her place very clean and organized, Nico said. " To be humble, respect your elders and take care of family and community. “ This is what we teach our children: you have two little eyes to see, two little ears to hear, and two little nostrils to smell with but you have only one mouth. You must listen more than you talk. I try to do that,” she said. “People used to come in and say 'Wow, your mom is so quiet, so regal,' but she was just being who she was, a good Cheyenne woman. Nico explained she herself is just one Cheyenne woman and can't speak for the Nation but through stories told by her relatives and on the reservation, she has created her life to carry on certain traditions. One of the things that is quite important to her is the Cheyenne language, and how names are given. “So, having 'Strange Owl‘ as a last name was because of the government,” she explained. The original Strange Owl was her great-grandfather and when her ancestors were put on the reservation in Montana, they decided that all of his nuclear family would have “Strange Owl” as their last name. “They gave him the first name of John,” she said. Her great-grandmother's name was Turtle Ribs, but was given the name “Mary,” so she became Mary Strange Owl. Nico's real name is Appearing Buffalo Woman, “a buffalo transforming into a woman,” she explained – in Cheyenne, it's spelled Esevonenameh'ne'. Original names are what are used among her Nation, between each other, she said. Her son's name is Dah'som, the name of a grandfather on the reservation her mother grew up with who was very light-hearted, funny, and loved to make people laugh. But in order to use that name, her mother had to get permission to do so. She had to give a reason and, in this case, it was because she honored the grandfather and wanted his traits to be part of Dah'som's life and persona. “You can only give a name four times,” Nico explained. For example, her mother's name was Blue Wing and she gave it away three times, but then her mother gave it away a fourth time. “She was really mad her mother did that, so she gave her own name (which means she needed another) to my granddaughter,” said Nico. Nico spends as much time as she can with the youngest Blue Wing, teaching her Cheyenne language and customs. Ann's new name was Medicine Eagle Feather Woman, “which she didn't like,” said Nico. “She thought it was too long.” Preserving the Cheyenne language is very important. A Cheyenne prophet, Sweet Medicine, who had many predictions that came true, said that when the Cheyenne lost their language, “a yellow-toothed monster would eat the world,” Nico said. She was concerned when the renaming of a mountain in Colorado from its English name - which was derogatory and sexist - to the Cheyenne name for Owl Woman: Mestaa'ėhehe (pronounced mess-taw-HAY) was criticized by the governor. Polis thought it was “too hard to pronounce,” and initially objected to it. Recently, he agreed to the name but warned against using hard-to-pronounce names in the future, arguing it would make people revert back to the original, offensive name it was trying to remedy. The Cheyenne etiquette can be interpreted as opposite of mainstream etiquette, she said. White people are called vé'ho'e, meaning spider, because they wore woven clothes (like a spider's web) and/or because they carved up the land with fences, rail lines, and farms. Unlike the vé'ho'e, in the Cheyenne Nation, you are considered most honorable if you give things away and if you own very little possessions. For example, when Nico and her cousin came of age, their grandmother on the reservation honored them by buying a buffalo and taught the girls how to clean and dress the entire animal. Being young, they tried to take a short cut by putting a garden hose through the intestine which made it flop all over the place. “My grandmother was very angry about that,” remembered Nico. Every part of the bison was used; the tendon that run from the shoulder to the tail along the back was made into sinew, thread for jewelry making. The hide was tanned. There were strips of meat cut and dried; the bones were preserved for carvings. And every bit of the meat was given away. This brought great honor to the two girls, who were learning what it meant to be Cheyenne women. “Every part of the animal is used,” Nico explained; there is no waste. The animal was thanked for the high honor of providing its life for the sustenance of others. “I hunt and I always thank the animal for its life,” she said. “I think all hunters do that – it's instinctual; it's a powerful moment when an animal dies while you are there. “We have a long history with the Earth; our creation story speaks of the Creator asking a bird to find him some land because there was nothing but water, so the bird dove down and brought up mud. The Creator then turned that little piece of mud into land. The earth is miraculous and precious,” Nico said. She was taught about the plants that act as medicines and how you should only take what you need and leave the rest. “You never pull up sage from the roots,” she says about the sage that grows around Eagle Plumes. She uses the sage to pray herself, greeting the sun each day. There are greens and mushrooms that can be eaten in the area, and there used to be thimble berries (tiny raspberries) that grew all over the site where Eagle Plume's sits, even moss on the trees. Global warming has changed a lot of that, she said. The area in and around Rocky Mountain National Park was part of the Cheyenne's culture, providing sustenance and ceremonial sites; they came up from their land east of the foothills and north of Denver to hunt, gather berries in the canyons, and worship. Lodgepole pines from the Tahosa Valley where Eagle Plume's sits were also used. “This land around here is part of my genetic heritage,” said Nico, “it's not a mistake that I am here.” There's something about Eagle Plume's, Nico Strange Owl (Esevonenameh'ne'), and the traditions she is trying to preserve that make me stop and think. What would it be like if everyone in the world would give more than they take, if you could create family by giving gifts, and if everyone fully understood the ramifications of disrespecting the land they live on? This article was published in the November 2021 edition of HIKE ROCKY magazine.  Barb Boyer Buck is a professional writer, journalist, editor, photographer, playwright, and researcher who lives in Estes Park. Barb is the managing editor of HIKE ROCKY online magazine. by Cindy Elkins How do we begin to accept our responsibility as travelers on this planet when our existence is temporary? Discovering what came before and accepting that there will be many future generations once I am gone, makes me ponder why it is so important to “Preserve and Protect.” Learning about past inhabitants and establishments while imagining the flying cars of the future, I appreciate my simplistic understanding of what it would have been like 10,000 years ago in the high country of what is now RMNP. Thinking about surviving the elements, hunting for bison or mammoth, foraging for food and being in a landscape recently carved by glaciers, I appreciate that my interactions with Rocky are purely recreational. Imagine seeing the base of Lumpy Ridge covered in the skulls of bison after a great hunt, or witnessing the competition between Arapahoe and Ute nations for hunting rights next time you are hiking the trails. This article is an attempt to give a glimpse of who was here before the Euro-American settlers came west. According to https://www.nps.gov/romo/learn/historyculture/tim e_line_of_historic_events.htm : “The…Clovis Paleoindian hunters entered the park as the glaciers retreated around 10,000 BC… and from 6000 BC to around 150 AD Archaic hunter-gatherers occupied areas of the park as seasonal hunters in the spring and summer months. These are the ancestors to many of the tribes in the western United States including the Ute, Comanche, Goshiute and Shoshone... Sometime around 1200 -1300 AD members of the Ute Nation enter into Colorado's North Park and Middle Park as well as areas of Rocky Mountain National Park… It is believed that around 1500 AD the Apache are in the high country of what is now the Rocky Mountain National Park... Members of the Arapaho Nation are believed to arrive in Rocky early in the 1800's. Shortly thereafter in 1820, the Stephen A. Long Expedition comes along and names Long's Peak as his own. "They are reported as the first non-Indians to see the area.” Just over 200 years ago the Euro-American's arrived to an area that had supported and provided for our human ancestors for over 11,000 years. That is something to ponder. In my opinion, we have an obligation to respect those who were here prior and those who will come through after we are gone. There have been several discoveries within the boundaries of Rocky Mountain National Park. Remnants of wooden shelters called wickiups date back 300 years. Traces of ancient hunts can be found in Rocky. Low rock walls, still in place today, were once used to guide game to their death. Once a happy hunting ground for nomadic tribes, now a thriving artist, tourist and outdoor-adventure mecca, RMNP has had many faces. A rock outcropping near Beaver Meadows designates where a fierce battle was once fought. The magnificent Ute Trail which is named for some of the original people who used it, crosses through all three elevation life zones that are in Rocky: alpine tundra (11,000 ft and up), subalpine zone (9k-11k), montane zone (5600-9500 ft). This hike was one of the main foot paths to cross the continental divide. It can be started up on Trail Ridge and is a well-marked hike down, or go up it. Nestled on the northwestern edge of Estes Park, 8310 feet or 2533 meters above sea level, Old Man Mountain is a granite silhouette of an elder looking west. A magnificently powerful mountain that is protected, so please obey the signs. There are at least five locations that are known ritual sites up on Old Man. These are considered important archeological places as well as vision quest sites. Old Man Mountain is not public. It is considered a sacred site of Colorado and is mostly private land with no clear trail to summit. Remember that honoring traditions and respecting cultures builds community. We ask that anyone in our hiking community tread lightly when in the Park and all surrounding areas. So, who were the original inhabitants like that made their way through the west and flourished around Northern Colorado? Why did Joel Estes report that he and his family never saw nonwhite folks when they arrived to build their cattle ranch 1858? Piecing together history that is mostly oral or concluded by the discovery of artifacts, emphasizes the importance of the RMNP policy of leaving anything you find exactly where you found it. Report all finds or possible discoveries to the rangers, and take a selfie with it for prosperity sake! Clues come in all shapes and sizes. The image of arrowheads shows the similar and different tools that were hand made by chipping at stone. A practice that is found worldwide. Like the mammoth, buffalo and original elk herds, the last of the Native Americans were driven out. The Arapaho, Ute, Apache, all tribes who crossed through the area are part of the history; part of what makes this place so special. As a traveler, local or tourist, next time you are up in the Park or just dreaming about it, listen closely. The wild winds of Northern Colorado may just whisper a clue from the past that fuels your imagination. You may find yourself as you go hiking across peaks or through marshy fields of braided creeks. You maybe wondering what it was like before and knowing that if we do our part, there will always be the special places. Keep Rocky wild and free. References: https://www.nps.gov/romo/learn/historyculture/time _line_of_historic_events.htm https://www.nps.gov/romo/learn/education/upload/ Cultural-History-Of-RMNP-Teacher-Guide-Final.pdf https://www.eptrail.com/2014/10/24/snowbirds-not- new-to-the-estes-valley/ This article is included in the November 2021 edition of HIKE ROCKY magazine.  Born in the mountains of West Virginia, Cindy Elkins has called Colorado home since 1981. As a professional artist and teacher, hiking and the outdoors provide inspiration and keep her active. Lessons learned from Colorado's biggest, wildest fires (part 3)Note: the following story was included in the February 2021 edition of HIKE ROCKY magazine and is being reprinted to accompany the new documentary, FIRESTORMS by Barb Boyer Buck “Hope is not a strategy,” said David Wolf, fire chief for Estes Valley Fire Protection District, about the realization the Cameron Peak Fire, which started north of the Estes Valley on August 13, 2020, could burn straight toward his jurisdiction. “There was nothing but fuel” between the fire and Glen Haven after it jumped Highway 14, so Wolf started preparing for if it came this way. “The day (the Cameron Peak fire) started, we were coming home from Grand Lake, driving through the Kawuneeche Valley and I saw a plume on the horizon,” recalled Kevin Zagorda, chief of the Glen Haven Area Volunteer Fire Department. “I turned to my wife and said, that's fire.” Zagorda thought it may be coming from somewhere in the Never Summer Range, “but by the time we got up Trail Ridge Road and got to Medicine Bow curve, you could clearly see where it was coming from, and that it was big.” Rocky Mountain National Park's fire management officer, Mike Lewelling, started a response in conjunction with the National Forest Service right away. “At first, we thought it was in the Park,” he remembered. The northwest section of RMNP is some of the most remote wilderness in RMNP's boundaries. Lewelling started working with the forest service to pinpoint the fire's exact location, which turned out to be 15 miles southwest of Red Feather Lakes, less than 80 miles north of the communities around Glen Haven, the Estes Valley, and the northern border of RMNP. At first, the fire wasn't moving toward the Park, Lewelling said, so he and his team concentrated on preparing for if it did. “That first week, we were brought into the Forest Service planning efforts,” he said. He and the incident commander for the section of fire that was closest to RMNP flew over the fire to assess. “I wasn't too concerned until I flew over Chapin Pass, and realized if the fire went up and over, that's where our Willow Park cabin is (along Old Fall River Road), and that's the Fall River drainage – which goes right into Estes Park.” Lewelling said they identified a few places along Fall River where they could “maybe make a stand,” but it didn't look like any line they could establish would hold. So, efforts shifted to developing evacuation plans. Even though it hadn't yet reached the Park's boundaries, on August 18 2020, some sections of northwest RMNP were closed. A week later, the Cameron Peak fire made its “second push,” Lewelling said, “and it came into the Park pretty fast.” Due to the inaccessibility of that section of the Park, it was very difficult to pinpoint the exact location, but it was clear the fire was within RMNP's borders. But then, a very early snowstorm hit on September 8-9, one of the earliest snows with accumulation recorded since the late 1800s. This stalled the fire's progression. Over the next few months, the Cameron Peak Fire “didn't want to move south into upper Chapin Creek, the area we were worried about” Lewelling said. They used helicopters to sprinkle the leading edge with retardant, but that doesn't really do much unless ground crews could go in to follow it up, he explained. All they could do was hope the fire didn't move south. More dry and windy weather followed the early- September snowfall and crews continued to work the Cameron Peak fire over the next six weeks as it burned toward communities northheast of the Park, including Glen Haven. “We had become a Fire Wise community in July,” GHAVFD Chief Zagorda said; as soon as the fire started, the communities in the Glen Haven area began to prepare. “A lot of the property owners had done significant mitigation work before the fire even began, which was a big plus for us,” he said. “We also had updated our Community Wildfire Protection Plan earlier that year.” A volunteer organization, Team Rubicon, contacted Zagorda about doing mitigation work in the Glen Haven area earlier in 2020. Team Rubicon is a veteran's organization that provides humanitarian and recovery aid to communities all over the country. “We took a look at our vulnerabilities and knew we were vulnerable in any of the drainages (ie, Miller Fort, North Fork, West Creek), so we knew we wanted to do some thinning of trees and other mitigation work toward the edge of developed areas.” An area in the North Fork drainage was completed and an area around the Retreat was partially completed, Zagorda said. “And then, a couple of weeks before the fire, Larimer County contacted me. Their fuels crew wanted to come up and do some work in Glen Haven.” They were going to finish the area around the Retreat in September. But by then, everyone was engaged in actively fighting this fire, which ended up burning 208,913 acres in Larimer and Jackson counties, making it the largest wildfire in Colorado's history. On October 14, the Cameron Peak fire made a “pretty big run on a red-flag day, I think it was a 12-mile run, that fire came down Panic Pass and down the Miller Fork drainage and got into the Retreat, just outside the developed areas.” But where Team Rubicon did fuel reduction, “it took a lot of the punch out of the fire,” Zagorda said. As a result, and with a little help from the weather which had turned cold again, his team was able to battle the fire directly in those areas, keeping it away from homes. This effort was bolstered a lot by the mitigation work the property owners had done, earlier that year. “I sat up there at the lookout point and watched the fire coming down the hill. It was very smoky, you couldn't see very much, but I was convinced a lot of those homes were going to be lost. As the smoke began to clear, you could see the fire come down and burn around the houses, because of the mitigation work the property owners had done,” Zagorda reported. Another thing that helped prepare for this fire was a community workshop on how to develop an evacuation plan, held by the department in August. GHAVFD and EVFPD helped Larimer County with evacuations and then got quickly to work on “rapid structure protection,” Zagorda explained. In about five minutes at each property, the crew worked to remove all combustibles away from the house did some quick chainsaw work on vegetation, and sprayed a little fire- fighting foam. “And then we had to back out and wait for the weather to cooperate before we could fight the fire directly.” The community of Glen Haven lost one home and three second homes. Several building and outbuildings were lost as well. No human or animal lives were lost in this area. The fire came within one-third of mile from Zagorda's house; he and his wife were evacuated for three weeks during which they moved seven times. Interagency cooperation and joint efforts are extremely important when fighting wildland fire, and with training efforts. Chief Wolf from the Estes Valley district, led a strike-force commander training session earlier that year which Zagorda credited as being very valuable during this fire. “Estes Valley and Glen Haven have a very good working relationship, we are mutual aid partners and we train together,” he said. Type I incident command teams arrive at big, dangerous fires – they are made up from crews from all over the country and serve about 2-3 weeks before another team is deployed. When they arrived at Glen Haven, they helped with setting up sprinkler systems for structure protection, bringing that equipment from the Red Feather Lakes area. Lewelling's crew began efforts in the Glen Haven area at about this time, too – the National Park was now on fire near its northeastern border, burning around Signal Mountain before back-burning about 300 acres into RMNP land and threatening the North Fork ranger cabin. “Make friends before you need them.” Lewelling got this piece of advice at the beginning of his career and with firefighting, it's absolutely essential. Wildfire doesn't respect jurisdiction lines and interagency cooperation and communication is key to successful fire management. The same day the Cameron Peak fire made its epic run toward the communities surrounding Glen Haven, the East Troublesome fire began on the west side of the Continental Divide. Along with serving as the assistant chief of the Grand County Fire Protection District 1, Schelly Olson is a public information officer for for fire incident teams, going out on fires all over the country. Many times, she is not necessarily working local fires; in fact, that summer she had been on a couple of fires in Arizona and then the Williams Fork Fire, 10 miles southwest of Fraser. “I had been on the Williams Fork fire for almost 50 days,” Olson said. She and a friend from Eagle County, also a PIO, needed some rest so they bought plane tickets to take a short vacation in Florida. The forest service called on October 14 to see if Olson could be PIO for the East Troublesome fire, but she declined because she had already booked the tickets. “I felt tremendous guilt because here was a fire in my county, and I'm leaving. “I did not know what (the East Troublesome fire) was going to do,” she said. She was still in Florida when the fire blew up the following Wednesday. It had been a tough fire season for those in Grand County, reported the Grand Fire Protections District 1 chief, Brad White, with multiple fires in the region. “Most of us lived under smoke clouds the entire summer,” White reported. Centrally located near Granby, his crew is often called out for interagency work as well. But when the East Troublesome fire started, White and seven other members of his crew were on quarantine for a known exposure to someone with an active COVID infection. The chief was working from home when he got a call from the Grand County sheriff, wanting to put part of White's district under a pre-evacuation order– the fire had burned 3,800 acres that first day. “Well, I said that's fine but I want to get a look at this fire myself.” After he assessed what the fire was doing, he contacted the sheriff and advised evacuation zones needed to be established all the way to Highway 34. There are a total of 5 fire protection districts that serve Grand County which is 1,870 square miles in area. They all perform mutual aid within the county, and with federal land management agencies - the forest service and national park service. The incident command team that had been dispatched to the Williams Fork fire stepped up as well. “October is a bad time of year to try to get federal resources so the (incident command) team was already thin. But not only did they agree to take on this new fire, they agreed to stay an additional week,” White said. Over the next couple of days, the fire grew from near Kremmling to the Hot Sulphur Springs area. On October 19, the wind started picking up again. “It was a pretty active few days, with air tankers dropping slurry,” White remembered. On the morning of the 21st, crews predicted the fire might cross Highway 125, where a few homes and ranches were located, so all those people were evacuated. “We felt pretty good because the fire was moving rapidly, but it was moving northeast toward Gravel Mountain,” away from more populated areas in an area where the fire could be boxed in. The mountain area mutual aid group (MAMA), which had been formed several years prior with 10 other Colorado counties, had been contact to help expedite resources and help with the evacuation of the Trail Creek subdivision, located off County Road 4 west of Lake Granby. But around 7 p.m. on the evening of the 21st, White realized something different was happening. “It got really dark up there,” he said, “the smoke column settled down and the winds really picked up.” From about 7-8:30 pm MAMA was involved in evacuations throughout the district and then started to try to protect structures. Similar to what Chief Zagorda and his crews were doing in Glen Haven, these crew members tried to save homes by removing combustibles from around the homes that were threatened. “At one point, I figured out the fire had traveled 17 miles in 90 minutes,” White said. “That's not the kind of fire you put fire fighters in front of.” In Grand County, “we lost 366 homes and I'll bet we lost 300 of them in that first big blow-up.” Meanwhile, back in Florida, Olson's phone was blowing up with calls from people asking where she was, how they should evacuate, etc. She was also receiving evacuation notifications for her home. “My husband was home alone and he wasn't signed up for emergency notifications so I relayed them to him,” she said. Because the fire blew up so quickly, he had about 10 minutes between the pre-evac notice and mandatory evacuation orders. “He was not able to pack up anything, only get himself, some clothes and our dog Rambo out,” she recalled. “I found out about the house at 2 o-clock in the morning, “We had a very large heavy-timber solid log home – the logs were 24 inches in diameter. Very hard to burn.” But nevertheless, the house burned to the ground, a complete loss. Olson's husband, Jeff, reported he could see the orange glow, feel the heat and extreme wind, and that it sounded like a freight train coming toward him, just prior to his evacuation. “Our house sat on the top of a hill and right behind us was a golf course. In front of us was the road, and on the other side of the road was marshy swamp land and then the Winding River Ranch. The ranch was a huge open space, no trees, only grass.” A few of the homeowners including the Olsons, had removed trees closest to their structures for a buffer, “but obviously, none of us had enough of a buffer.” The surrounding terrain, which logically should have provided fire breaks, didn't help either. Olson explained why: “The wind blew giant embers ahead of the fire. Everything was pre-heated because of that hot wind. Fuel can start combusting, even without that direct- flame impingement. The embers just showered down and landed on everything,” Olson said. In other cases, windows were blown out and embers got inside homes, burning them from the inside out. “The engine block that was in the car in our garage just melted onto the concrete floor, creating what looked like a sculpture,” she said. All of her jewelry was pulverized by the extreme heat. Meanwhile, on the east side of the Divide, Lewelling was discussing evacuation plans for Park personnel with the district ranger in the Kawuneeche Valley. “When she told me the fire was at Sloopy's – the burger joint just south of the Park - it really hit home.” Park personnel stationed on the west side of Rocky evacuated over Trail Ridge Road and reached the emergency command center at midnight– where Lewelling, Wolf, and many other officials were coordinating efforts. “A big part of this story is what you see in people's eyes,” Lewelling said. “We're all professionals with many years of experience, but you could see it in people's eyes – this was different. This was a different event.” Lewelling thought that was all that was going to happen for the night. “Certainly, it wasn't going to cross the Continental Divide,” he thought. But first thing in the morning of the 22nd, he got a call from the National Weather Service, telling him weather satellites detected a heat signature on the east side of the Divide. “From how much the wind could blow the smoke column, that signal could just be embers in the smoke column. It doesn't mean there is fire on the ground,” Chief Wolf said when he first heard about the weather satellite's detection. Mid-morning, it became clear the fire had indeed jumped the Divide and was working its way to the Fern Lake burn scar. Around noon that day, the emergency management team started working on an evacuation plan for the Highway 66 corridor. It was still not clear how far the down the fire had gotten down into the east side of the Park because of the heavy smoke that was billowing out in front of it. By the time it was confirmed, the fire had reached Mount Wuh and had already blown past one of the evacuation triggers, Wolf said. The triggers were set by a joint emergency management team in 2017, which predicted what would happen if a fire which started in Rocky got into one of the drainages leading into the community of Estes Park. These models predicted such a fire under worst-case scenarios would burn through the town in four hours. The current situation was worse than any scenario imagined. It was time to act quickly. By 2 p.m., for the first time in history, the entire Estes Valley was under a voluntary evacuation order; by Saturday, October 24, the order was upgraded to mandatory for everyone in the valley. “Since law enforcement was handling the evacuations, we were able to focus on other priorities, such as protecting our communications, the hospital, and long-term care facilities, knowing that they would need more time for evacuations,” Wolf explained. Another concern was the water supply. “We knew that the number of resources we had were not going to be enough for the fire fight we were expecting,” Wolf said. Emergency management called out for more resources and were rewarded with a lot of assistance from communities along the Front Range. Saturday night, the local crews could finally have a night off. But at 2 in the morning Sunday, they got another call – a structure fire, unrelated to the wildfires, burned down a home. Sunday morning, everyone was happy to wake up to snow, Wolf said. But now that electricity and gas had been turned off to all the valley's structures, there was a danger of freezing pipes. So, crews helped to winterize homes, and get pilot lights re-lit. The planning that occurred in 2017, organized by Lewelling and Wolf and with the input of many other emergency management personnel was extremely useful during this event, Wolf said. “We thought we would be fighting fire on Elkhorn Avenue by the end of the day,” Wolf said. Luckily, that wasn't the case. “Overall, when we look at what happened with the Cameron Peak and East Troublesome fires, I would say that we were very successful. We were also very lucky,” Wolf said. Efficiency in interagency coordination and cooperation, planning for worst-case scenarios, and effective mobilization of resources was a lesson already learned by Zagorda, Wolf, and Lewelling, thankfully. But one thing that they hadn't thought of is where they would get food- they had just evacuated everyone, including the grocery stores and restaurants. For Chief Zagorda, the fuels mitigation work conducted by volunteers and homeowners saved quite a few homes. Asst. Chief Olson said that one of the lessons learned was to install reflective house numbering, so addresses can be found quickly in an emergency. “Grand County is ground zero for the pine beetle infestation,” which killed 95% of the lodgepole forests, she said. “Fuels mitigation is a big part of this.” Prescribed fires and fuel reduction in Rocky was instrumental in keeping the fire west of the Estes Valley, several of the fire management professionals noted.

All of the fire agencies who were approached for this article depend heavily on volunteers, there are very few career fire- fighters. In areas such as Glen Haven, a non-incorporated community in Larimer County, “every pair of hands and feet were working to fight the fire,” Zagorda said. Both of these fires ended up burning approximately 400,000 acres in northern Colorado; the East Troublesome came in just behind the Cameron Peak fire to be the second largest fire in Colorado's history. Within Rocky's boundaries, 30,000 acres were burned – more than in any other in its 106-year history. Both of these fires, along with most of Colorado's wildfires in 2020, were human caused; the exact causes are under investigation. Since wildfire isn't going away, it's clear the biggest lessons learned from these fires is that the general public needs to become more educated on their responsibilities while recreating in the wilderness Each of these agencies provide community resources on their websites. Visit the Glen Haven Area Volunteer Fire Department at www.ghavfd.org Schelly Olson has created a nonprofit organization called the Grand County Wildfire Council: bewildfireready.org/ Grand Fire Protection District 1 can be found at grandfire.org/ The Estes Valley FPD's website is: www.estesvalleyfire.org/ Rocky Mountain National Park's fire management office can be found here: www.nps.gov/romo/learn/management/firemanagement.html |

Categories

All

|

© Copyright 2025 Barefoot Publications, All Rights Reserved