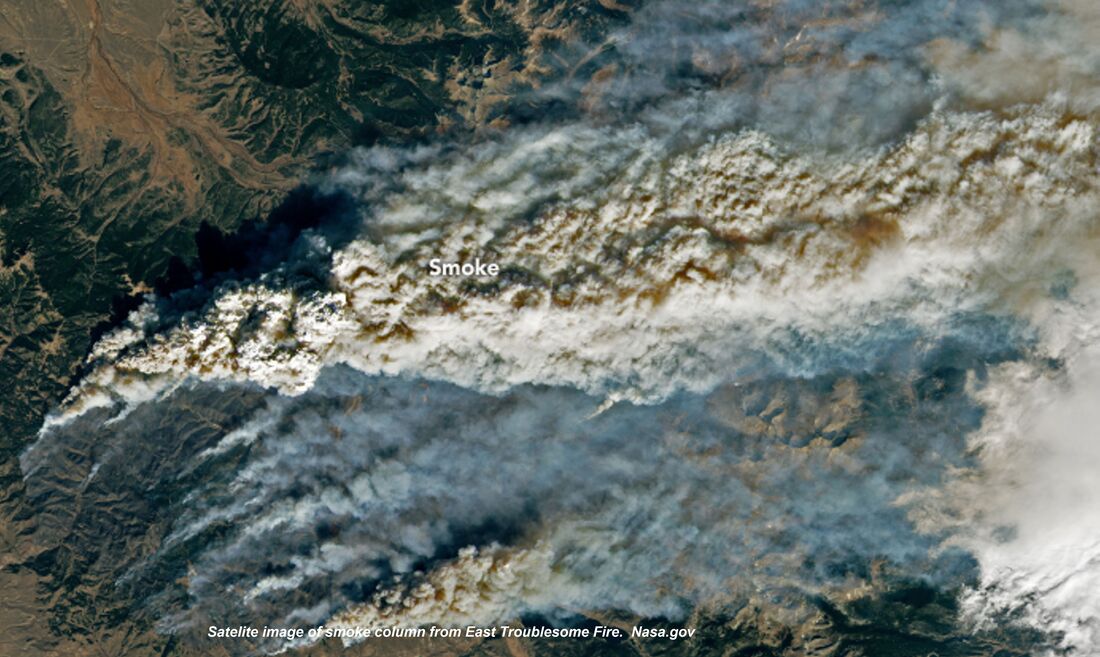

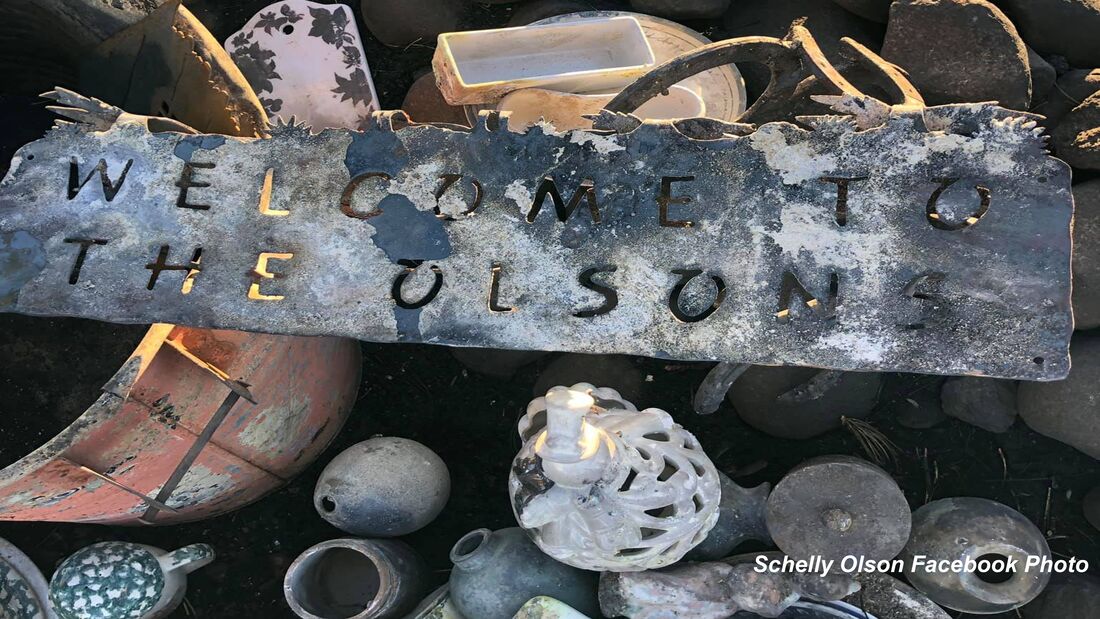

Lessons learned from Colorado's biggest, wildest fires (part 3)Note: the following story was included in the February 2021 edition of HIKE ROCKY magazine and is being reprinted to accompany the new documentary, FIRESTORMS by Barb Boyer Buck “Hope is not a strategy,” said David Wolf, fire chief for Estes Valley Fire Protection District, about the realization the Cameron Peak Fire, which started north of the Estes Valley on August 13, 2020, could burn straight toward his jurisdiction. “There was nothing but fuel” between the fire and Glen Haven after it jumped Highway 14, so Wolf started preparing for if it came this way. “The day (the Cameron Peak fire) started, we were coming home from Grand Lake, driving through the Kawuneeche Valley and I saw a plume on the horizon,” recalled Kevin Zagorda, chief of the Glen Haven Area Volunteer Fire Department. “I turned to my wife and said, that's fire.” Zagorda thought it may be coming from somewhere in the Never Summer Range, “but by the time we got up Trail Ridge Road and got to Medicine Bow curve, you could clearly see where it was coming from, and that it was big.” Rocky Mountain National Park's fire management officer, Mike Lewelling, started a response in conjunction with the National Forest Service right away. “At first, we thought it was in the Park,” he remembered. The northwest section of RMNP is some of the most remote wilderness in RMNP's boundaries. Lewelling started working with the forest service to pinpoint the fire's exact location, which turned out to be 15 miles southwest of Red Feather Lakes, less than 80 miles north of the communities around Glen Haven, the Estes Valley, and the northern border of RMNP. At first, the fire wasn't moving toward the Park, Lewelling said, so he and his team concentrated on preparing for if it did. “That first week, we were brought into the Forest Service planning efforts,” he said. He and the incident commander for the section of fire that was closest to RMNP flew over the fire to assess. “I wasn't too concerned until I flew over Chapin Pass, and realized if the fire went up and over, that's where our Willow Park cabin is (along Old Fall River Road), and that's the Fall River drainage – which goes right into Estes Park.” Lewelling said they identified a few places along Fall River where they could “maybe make a stand,” but it didn't look like any line they could establish would hold. So, efforts shifted to developing evacuation plans. Even though it hadn't yet reached the Park's boundaries, on August 18 2020, some sections of northwest RMNP were closed. A week later, the Cameron Peak fire made its “second push,” Lewelling said, “and it came into the Park pretty fast.” Due to the inaccessibility of that section of the Park, it was very difficult to pinpoint the exact location, but it was clear the fire was within RMNP's borders. But then, a very early snowstorm hit on September 8-9, one of the earliest snows with accumulation recorded since the late 1800s. This stalled the fire's progression. Over the next few months, the Cameron Peak Fire “didn't want to move south into upper Chapin Creek, the area we were worried about” Lewelling said. They used helicopters to sprinkle the leading edge with retardant, but that doesn't really do much unless ground crews could go in to follow it up, he explained. All they could do was hope the fire didn't move south. More dry and windy weather followed the early- September snowfall and crews continued to work the Cameron Peak fire over the next six weeks as it burned toward communities northheast of the Park, including Glen Haven. “We had become a Fire Wise community in July,” GHAVFD Chief Zagorda said; as soon as the fire started, the communities in the Glen Haven area began to prepare. “A lot of the property owners had done significant mitigation work before the fire even began, which was a big plus for us,” he said. “We also had updated our Community Wildfire Protection Plan earlier that year.” A volunteer organization, Team Rubicon, contacted Zagorda about doing mitigation work in the Glen Haven area earlier in 2020. Team Rubicon is a veteran's organization that provides humanitarian and recovery aid to communities all over the country. “We took a look at our vulnerabilities and knew we were vulnerable in any of the drainages (ie, Miller Fort, North Fork, West Creek), so we knew we wanted to do some thinning of trees and other mitigation work toward the edge of developed areas.” An area in the North Fork drainage was completed and an area around the Retreat was partially completed, Zagorda said. “And then, a couple of weeks before the fire, Larimer County contacted me. Their fuels crew wanted to come up and do some work in Glen Haven.” They were going to finish the area around the Retreat in September. But by then, everyone was engaged in actively fighting this fire, which ended up burning 208,913 acres in Larimer and Jackson counties, making it the largest wildfire in Colorado's history. On October 14, the Cameron Peak fire made a “pretty big run on a red-flag day, I think it was a 12-mile run, that fire came down Panic Pass and down the Miller Fork drainage and got into the Retreat, just outside the developed areas.” But where Team Rubicon did fuel reduction, “it took a lot of the punch out of the fire,” Zagorda said. As a result, and with a little help from the weather which had turned cold again, his team was able to battle the fire directly in those areas, keeping it away from homes. This effort was bolstered a lot by the mitigation work the property owners had done, earlier that year. “I sat up there at the lookout point and watched the fire coming down the hill. It was very smoky, you couldn't see very much, but I was convinced a lot of those homes were going to be lost. As the smoke began to clear, you could see the fire come down and burn around the houses, because of the mitigation work the property owners had done,” Zagorda reported. Another thing that helped prepare for this fire was a community workshop on how to develop an evacuation plan, held by the department in August. GHAVFD and EVFPD helped Larimer County with evacuations and then got quickly to work on “rapid structure protection,” Zagorda explained. In about five minutes at each property, the crew worked to remove all combustibles away from the house did some quick chainsaw work on vegetation, and sprayed a little fire- fighting foam. “And then we had to back out and wait for the weather to cooperate before we could fight the fire directly.” The community of Glen Haven lost one home and three second homes. Several building and outbuildings were lost as well. No human or animal lives were lost in this area. The fire came within one-third of mile from Zagorda's house; he and his wife were evacuated for three weeks during which they moved seven times. Interagency cooperation and joint efforts are extremely important when fighting wildland fire, and with training efforts. Chief Wolf from the Estes Valley district, led a strike-force commander training session earlier that year which Zagorda credited as being very valuable during this fire. “Estes Valley and Glen Haven have a very good working relationship, we are mutual aid partners and we train together,” he said. Type I incident command teams arrive at big, dangerous fires – they are made up from crews from all over the country and serve about 2-3 weeks before another team is deployed. When they arrived at Glen Haven, they helped with setting up sprinkler systems for structure protection, bringing that equipment from the Red Feather Lakes area. Lewelling's crew began efforts in the Glen Haven area at about this time, too – the National Park was now on fire near its northeastern border, burning around Signal Mountain before back-burning about 300 acres into RMNP land and threatening the North Fork ranger cabin. “Make friends before you need them.” Lewelling got this piece of advice at the beginning of his career and with firefighting, it's absolutely essential. Wildfire doesn't respect jurisdiction lines and interagency cooperation and communication is key to successful fire management. The same day the Cameron Peak fire made its epic run toward the communities surrounding Glen Haven, the East Troublesome fire began on the west side of the Continental Divide. Along with serving as the assistant chief of the Grand County Fire Protection District 1, Schelly Olson is a public information officer for for fire incident teams, going out on fires all over the country. Many times, she is not necessarily working local fires; in fact, that summer she had been on a couple of fires in Arizona and then the Williams Fork Fire, 10 miles southwest of Fraser. “I had been on the Williams Fork fire for almost 50 days,” Olson said. She and a friend from Eagle County, also a PIO, needed some rest so they bought plane tickets to take a short vacation in Florida. The forest service called on October 14 to see if Olson could be PIO for the East Troublesome fire, but she declined because she had already booked the tickets. “I felt tremendous guilt because here was a fire in my county, and I'm leaving. “I did not know what (the East Troublesome fire) was going to do,” she said. She was still in Florida when the fire blew up the following Wednesday. It had been a tough fire season for those in Grand County, reported the Grand Fire Protections District 1 chief, Brad White, with multiple fires in the region. “Most of us lived under smoke clouds the entire summer,” White reported. Centrally located near Granby, his crew is often called out for interagency work as well. But when the East Troublesome fire started, White and seven other members of his crew were on quarantine for a known exposure to someone with an active COVID infection. The chief was working from home when he got a call from the Grand County sheriff, wanting to put part of White's district under a pre-evacuation order– the fire had burned 3,800 acres that first day. “Well, I said that's fine but I want to get a look at this fire myself.” After he assessed what the fire was doing, he contacted the sheriff and advised evacuation zones needed to be established all the way to Highway 34. There are a total of 5 fire protection districts that serve Grand County which is 1,870 square miles in area. They all perform mutual aid within the county, and with federal land management agencies - the forest service and national park service. The incident command team that had been dispatched to the Williams Fork fire stepped up as well. “October is a bad time of year to try to get federal resources so the (incident command) team was already thin. But not only did they agree to take on this new fire, they agreed to stay an additional week,” White said. Over the next couple of days, the fire grew from near Kremmling to the Hot Sulphur Springs area. On October 19, the wind started picking up again. “It was a pretty active few days, with air tankers dropping slurry,” White remembered. On the morning of the 21st, crews predicted the fire might cross Highway 125, where a few homes and ranches were located, so all those people were evacuated. “We felt pretty good because the fire was moving rapidly, but it was moving northeast toward Gravel Mountain,” away from more populated areas in an area where the fire could be boxed in. The mountain area mutual aid group (MAMA), which had been formed several years prior with 10 other Colorado counties, had been contact to help expedite resources and help with the evacuation of the Trail Creek subdivision, located off County Road 4 west of Lake Granby. But around 7 p.m. on the evening of the 21st, White realized something different was happening. “It got really dark up there,” he said, “the smoke column settled down and the winds really picked up.” From about 7-8:30 pm MAMA was involved in evacuations throughout the district and then started to try to protect structures. Similar to what Chief Zagorda and his crews were doing in Glen Haven, these crew members tried to save homes by removing combustibles from around the homes that were threatened. “At one point, I figured out the fire had traveled 17 miles in 90 minutes,” White said. “That's not the kind of fire you put fire fighters in front of.” In Grand County, “we lost 366 homes and I'll bet we lost 300 of them in that first big blow-up.” Meanwhile, back in Florida, Olson's phone was blowing up with calls from people asking where she was, how they should evacuate, etc. She was also receiving evacuation notifications for her home. “My husband was home alone and he wasn't signed up for emergency notifications so I relayed them to him,” she said. Because the fire blew up so quickly, he had about 10 minutes between the pre-evac notice and mandatory evacuation orders. “He was not able to pack up anything, only get himself, some clothes and our dog Rambo out,” she recalled. “I found out about the house at 2 o-clock in the morning, “We had a very large heavy-timber solid log home – the logs were 24 inches in diameter. Very hard to burn.” But nevertheless, the house burned to the ground, a complete loss. Olson's husband, Jeff, reported he could see the orange glow, feel the heat and extreme wind, and that it sounded like a freight train coming toward him, just prior to his evacuation. “Our house sat on the top of a hill and right behind us was a golf course. In front of us was the road, and on the other side of the road was marshy swamp land and then the Winding River Ranch. The ranch was a huge open space, no trees, only grass.” A few of the homeowners including the Olsons, had removed trees closest to their structures for a buffer, “but obviously, none of us had enough of a buffer.” The surrounding terrain, which logically should have provided fire breaks, didn't help either. Olson explained why: “The wind blew giant embers ahead of the fire. Everything was pre-heated because of that hot wind. Fuel can start combusting, even without that direct- flame impingement. The embers just showered down and landed on everything,” Olson said. In other cases, windows were blown out and embers got inside homes, burning them from the inside out. “The engine block that was in the car in our garage just melted onto the concrete floor, creating what looked like a sculpture,” she said. All of her jewelry was pulverized by the extreme heat. Meanwhile, on the east side of the Divide, Lewelling was discussing evacuation plans for Park personnel with the district ranger in the Kawuneeche Valley. “When she told me the fire was at Sloopy's – the burger joint just south of the Park - it really hit home.” Park personnel stationed on the west side of Rocky evacuated over Trail Ridge Road and reached the emergency command center at midnight– where Lewelling, Wolf, and many other officials were coordinating efforts. “A big part of this story is what you see in people's eyes,” Lewelling said. “We're all professionals with many years of experience, but you could see it in people's eyes – this was different. This was a different event.” Lewelling thought that was all that was going to happen for the night. “Certainly, it wasn't going to cross the Continental Divide,” he thought. But first thing in the morning of the 22nd, he got a call from the National Weather Service, telling him weather satellites detected a heat signature on the east side of the Divide. “From how much the wind could blow the smoke column, that signal could just be embers in the smoke column. It doesn't mean there is fire on the ground,” Chief Wolf said when he first heard about the weather satellite's detection. Mid-morning, it became clear the fire had indeed jumped the Divide and was working its way to the Fern Lake burn scar. Around noon that day, the emergency management team started working on an evacuation plan for the Highway 66 corridor. It was still not clear how far the down the fire had gotten down into the east side of the Park because of the heavy smoke that was billowing out in front of it. By the time it was confirmed, the fire had reached Mount Wuh and had already blown past one of the evacuation triggers, Wolf said. The triggers were set by a joint emergency management team in 2017, which predicted what would happen if a fire which started in Rocky got into one of the drainages leading into the community of Estes Park. These models predicted such a fire under worst-case scenarios would burn through the town in four hours. The current situation was worse than any scenario imagined. It was time to act quickly. By 2 p.m., for the first time in history, the entire Estes Valley was under a voluntary evacuation order; by Saturday, October 24, the order was upgraded to mandatory for everyone in the valley. “Since law enforcement was handling the evacuations, we were able to focus on other priorities, such as protecting our communications, the hospital, and long-term care facilities, knowing that they would need more time for evacuations,” Wolf explained. Another concern was the water supply. “We knew that the number of resources we had were not going to be enough for the fire fight we were expecting,” Wolf said. Emergency management called out for more resources and were rewarded with a lot of assistance from communities along the Front Range. Saturday night, the local crews could finally have a night off. But at 2 in the morning Sunday, they got another call – a structure fire, unrelated to the wildfires, burned down a home. Sunday morning, everyone was happy to wake up to snow, Wolf said. But now that electricity and gas had been turned off to all the valley's structures, there was a danger of freezing pipes. So, crews helped to winterize homes, and get pilot lights re-lit. The planning that occurred in 2017, organized by Lewelling and Wolf and with the input of many other emergency management personnel was extremely useful during this event, Wolf said. “We thought we would be fighting fire on Elkhorn Avenue by the end of the day,” Wolf said. Luckily, that wasn't the case. “Overall, when we look at what happened with the Cameron Peak and East Troublesome fires, I would say that we were very successful. We were also very lucky,” Wolf said. Efficiency in interagency coordination and cooperation, planning for worst-case scenarios, and effective mobilization of resources was a lesson already learned by Zagorda, Wolf, and Lewelling, thankfully. But one thing that they hadn't thought of is where they would get food- they had just evacuated everyone, including the grocery stores and restaurants. For Chief Zagorda, the fuels mitigation work conducted by volunteers and homeowners saved quite a few homes. Asst. Chief Olson said that one of the lessons learned was to install reflective house numbering, so addresses can be found quickly in an emergency. “Grand County is ground zero for the pine beetle infestation,” which killed 95% of the lodgepole forests, she said. “Fuels mitigation is a big part of this.” Prescribed fires and fuel reduction in Rocky was instrumental in keeping the fire west of the Estes Valley, several of the fire management professionals noted.

All of the fire agencies who were approached for this article depend heavily on volunteers, there are very few career fire- fighters. In areas such as Glen Haven, a non-incorporated community in Larimer County, “every pair of hands and feet were working to fight the fire,” Zagorda said. Both of these fires ended up burning approximately 400,000 acres in northern Colorado; the East Troublesome came in just behind the Cameron Peak fire to be the second largest fire in Colorado's history. Within Rocky's boundaries, 30,000 acres were burned – more than in any other in its 106-year history. Both of these fires, along with most of Colorado's wildfires in 2020, were human caused; the exact causes are under investigation. Since wildfire isn't going away, it's clear the biggest lessons learned from these fires is that the general public needs to become more educated on their responsibilities while recreating in the wilderness Each of these agencies provide community resources on their websites. Visit the Glen Haven Area Volunteer Fire Department at www.ghavfd.org Schelly Olson has created a nonprofit organization called the Grand County Wildfire Council: bewildfireready.org/ Grand Fire Protection District 1 can be found at grandfire.org/ The Estes Valley FPD's website is: www.estesvalleyfire.org/ Rocky Mountain National Park's fire management office can be found here: www.nps.gov/romo/learn/management/firemanagement.html

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

|

© Copyright 2025 Barefoot Publications, All Rights Reserved