|

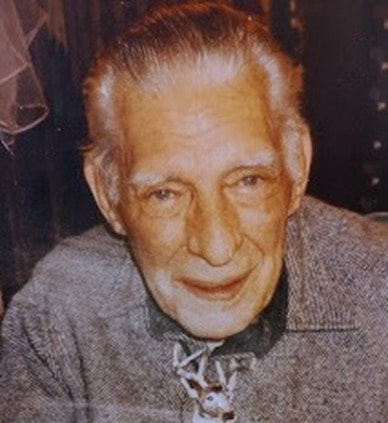

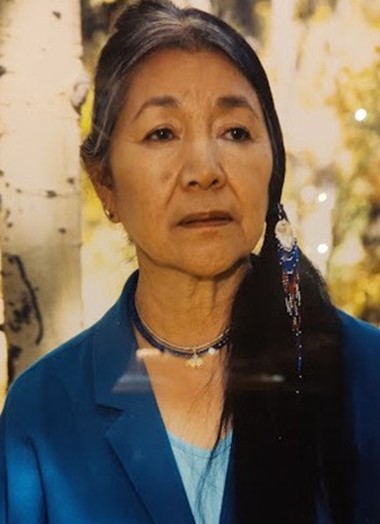

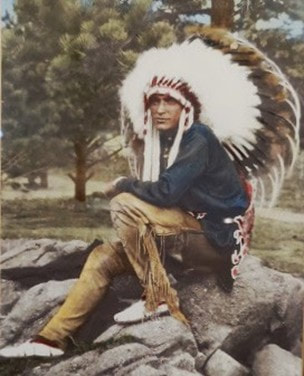

One Northern Cheyenne woman's perspective on life by Barb Boyer Buck Just a few minutes south of Estes Park, there is a remarkable place redolent with various traditions and history, both native and non-native. Eagle Plume's Trading Post, just over the Boulder County line on Highway 7, is owned by Nico Strange Owl, who took over the full operation after the recent deaths of her parents. Her father, Dayton Raben, passed last December of a stroke and her mother, Ann Strange Owl, lost her battle with Alzheimer's in July. Nico sat down with me last week to speak about the history of the place and her perspective on the traditions which formed her life. To'tseha (The History of of Eagle Plumes) The building itself was built in 1917. It was originally commissioned to look like a Kansas farmhouse by Katherine Lindsay who wanted to open an inn in the proposed town of Hewes-Kirkwood, slated to be developed in the area. Lindsay was an artist and painter in an early art-deco style; she opened the What Not Inn and decorated the establishment with her artwork and beadwork her father “collected” during in the Indian Wars in Kansas. The building next store was the grocery store.  Intricate beadwork is part of Eagle Plume's collection. Intricate beadwork is part of Eagle Plume's collection. After a few years, she realized there was not going to be a town; business was very seasonal and most people were heading to Estes Park or into the national park itself for their lodging needs. She had married a man named Perkins and they turned the inn into a trading post dealing in Native American art from the early to mid-1920s. Her husband was sickly and passed away soon after, so she hired Charles Eagle Plume in the mid-1930s. “He showed up on horseback one day,” said Nico, “and claimed to be one-quarter Blackfoot Indian from Montana. “He was a master marketer; he ran the place and made it famous. He would dress up in Native American regalia and pretend to shoot arrows at the passing cars and then point them toward the store.” Works purchased from Mrs. Perkins and Charles are housed in museum collections, including the Denver Art Museum.  Charles Eagle Plume as a young man Charles Eagle Plume as a young man “Together Charles and Mrs. Perkins built on their collection; they were close, he became like a son,” Nico said. “When she passed away in 1966, she left the store to Charles.” He was adamant about carrying only Native American-made art and goods. This holds true today, except for a line that is designed by Native Americans and made elsewhere. “In the beginning, we could find things to offer that were $5-$10, but not anymore. We carry these to be competitive,” Nico explained. Nico's parents moved to northern Colorado in 1966, when Dayton got a job as a history teacher in Berthoud. “When they got married, interracial marriage was illegal in Wyoming. He was a white man of German and Scots descent from that state, and she was a Cheyenne woman, working on the Wind River reservation. He fell in love with her right way; they were married within three months of meeting,” said Nico.  Dayton Raben and Ann Strange Owl Dayton Raben and Ann Strange Owl “When dad took mom to meet his family, some of them tried to buy her off to get the marriage annulled; they were horrified he had married a native woman. When mom introduced him to her family at her home in the Northern Cheyenne Reservation in Montana, some stared right through him as a sign of banishment,” Nico said. On the advice of his father, the couple moved to California where Nico was born. For the sake of the child, they wanted to get closer to family – “but not too close!” Nico said, which precipitated the move to Colorado. There were frequent trips to the reservation where Ann had lived, but she was feeling lonely for other native people in Colorado. She had an aunt who was southern Cheyenne; this woman lived in Denver because of the government's efforts to assimilate Native Americans into larger cities. "They were trying to take them away  Nico Strange Owl Nico Strange Owl from the native language and culture,” Nico said. Ann didn't feel at home with the Denver Indian community, so someone told them to visit Charlie at Eagle Plume's. “Charlie loved mom right away, he loved native people. He asked her to work for him at the trading post,” said Nico. He kept hounding her until she finally said yes in 1979. “They became really good friends and Charlie adopted mom in the native plains tradition.” In native plains tradition, a person can adopt another (even if they are not related by birth) by exchanging gifts, Nico explained. “Charlie gave her a Cheyenne dress with beaded boots; he made posters to sell from a photograph with her in that dress.” While Ann started working for Charlie in the summers, Dayton would come up and sit behind the shop and read books or take walks. Finally, Dayton was persuaded to work in the shop, too. He would regale the male customers with stories about the weapons in the collection while the women shopped, remembered Nico. Nico began working at the shop when she was getting her degree in Anthropology from Colorado State University. She would come up in the summer, sometimes with friends from college, to work (and nap!) in the shop. ”After a hard night out the day before, "We took turns taking naps up there." “When Charles caught us, he got very mad and made us fold the rugs. That was a horrible job,” she said. “Charles didn't have any children, so he created a buy/sell agreement with my parents, the bookkeeper, and the sales lady,” Nico explained. Immediately after Charles’ death in 1992, the bookkeeper and sales lady broke the agreement and put the store up for sale. “That was a horrible summer,” said Nico. “The sales lady was really prejudiced against Indians and Charles would defend my mom against her all the time.” But now he was gone, and two of the three members of agreement were trying to sell the shop. Nico recalls that through the summer, they hadn't really gotten any offers and curiously, the sales lady began declining in health rapidly; she had kyphosis - an exaggerated, forward-rounding of the back. One day, the bookkeeper came in and said she had changed her mind about selling. Why was that? Well, reported Nico, the bookkeeper had a dream where “Charles came to her, and he wasn’t happy” about the proposed sale. In 1993, the other two women were bought out by Nico's parents, who went on to run the store for the next 30 years with Nico's help. “it's funny, because Charles ran the place for 30 years before my parents got it,” Nico recalled, “and Mrs. Perkins ran it for 30 years before she went into a nursing home. “Before Charles passed away, I was packing up the collection at the end of the year to put it in storage while he gave instructions from his wheelchair. He looked at me and said, 'My dear, one day you will have a son and he will run this store.' I have one son but he doesn't want to run the store like it has been, so we'll see if it comes true.” Perhaps Nico has to run it for 30 years first? Nico was very close with her parents, and Charles. Charles helped get Nico her first job after college, at an Indian art gallery in Vail. “There was a couple that had an Indian shop in Vail and came in and asked Charles if they could consign his stuff for the winter (since Eagle Plume's was only open from mid-May to mid- September).” Charles pointed at Nico and said, “she has to be part of the deal. because he knew she wanted to ski. “So I went and managed their gallery and sold his stock so he could replenish for the next summer. It was crazy how much stuff he had.” So Nico skied, mountain biked, and sold Indian art in Vail for the next seven years. Then, she got married and moved to Denver where she put her now-ex through graduate school. After the divorce, Nico came back to run the store with her parents after Charles died. “We ran it for decades, and I miss them so much,” she said, “but I always knew they would go together, they were so close. After my father died, I had to retell my mother multiple times a day that he had passed,” Ann's Alzheimer's was taking control. “Every time, she would cry and mourn, it was terrible.” Finally in March, it sunk in her husband was gone, said Nico, and then Ann deteriorated quickly. “So now, it's just me and Kay (the current sales person), my son, and a few neighbors who come in and help; it's good,” said Nico. -tsėhésevo'ėstanéheve (to live as a Cheyenne) Today, Nico honors her father by telling his stories to people who come into the store and she honors her mother by trying to be a “good Cheyenne woman.” “What does it mean to be a good Cheyenne woman?” I asked her. “Well, I'm not a great Cheyenne woman,” she laughed, “but I try.” A good Cheyenne woman works hard and keeps her place very clean and organized, Nico said. " To be humble, respect your elders and take care of family and community. “ This is what we teach our children: you have two little eyes to see, two little ears to hear, and two little nostrils to smell with but you have only one mouth. You must listen more than you talk. I try to do that,” she said. “People used to come in and say 'Wow, your mom is so quiet, so regal,' but she was just being who she was, a good Cheyenne woman. Nico explained she herself is just one Cheyenne woman and can't speak for the Nation but through stories told by her relatives and on the reservation, she has created her life to carry on certain traditions. One of the things that is quite important to her is the Cheyenne language, and how names are given. “So, having 'Strange Owl‘ as a last name was because of the government,” she explained. The original Strange Owl was her great-grandfather and when her ancestors were put on the reservation in Montana, they decided that all of his nuclear family would have “Strange Owl” as their last name. “They gave him the first name of John,” she said. Her great-grandmother's name was Turtle Ribs, but was given the name “Mary,” so she became Mary Strange Owl. Nico's real name is Appearing Buffalo Woman, “a buffalo transforming into a woman,” she explained – in Cheyenne, it's spelled Esevonenameh'ne'. Original names are what are used among her Nation, between each other, she said. Her son's name is Dah'som, the name of a grandfather on the reservation her mother grew up with who was very light-hearted, funny, and loved to make people laugh. But in order to use that name, her mother had to get permission to do so. She had to give a reason and, in this case, it was because she honored the grandfather and wanted his traits to be part of Dah'som's life and persona. “You can only give a name four times,” Nico explained. For example, her mother's name was Blue Wing and she gave it away three times, but then her mother gave it away a fourth time. “She was really mad her mother did that, so she gave her own name (which means she needed another) to my granddaughter,” said Nico. Nico spends as much time as she can with the youngest Blue Wing, teaching her Cheyenne language and customs. Ann's new name was Medicine Eagle Feather Woman, “which she didn't like,” said Nico. “She thought it was too long.” Preserving the Cheyenne language is very important. A Cheyenne prophet, Sweet Medicine, who had many predictions that came true, said that when the Cheyenne lost their language, “a yellow-toothed monster would eat the world,” Nico said. She was concerned when the renaming of a mountain in Colorado from its English name - which was derogatory and sexist - to the Cheyenne name for Owl Woman: Mestaa'ėhehe (pronounced mess-taw-HAY) was criticized by the governor. Polis thought it was “too hard to pronounce,” and initially objected to it. Recently, he agreed to the name but warned against using hard-to-pronounce names in the future, arguing it would make people revert back to the original, offensive name it was trying to remedy. The Cheyenne etiquette can be interpreted as opposite of mainstream etiquette, she said. White people are called vé'ho'e, meaning spider, because they wore woven clothes (like a spider's web) and/or because they carved up the land with fences, rail lines, and farms. Unlike the vé'ho'e, in the Cheyenne Nation, you are considered most honorable if you give things away and if you own very little possessions. For example, when Nico and her cousin came of age, their grandmother on the reservation honored them by buying a buffalo and taught the girls how to clean and dress the entire animal. Being young, they tried to take a short cut by putting a garden hose through the intestine which made it flop all over the place. “My grandmother was very angry about that,” remembered Nico. Every part of the bison was used; the tendon that run from the shoulder to the tail along the back was made into sinew, thread for jewelry making. The hide was tanned. There were strips of meat cut and dried; the bones were preserved for carvings. And every bit of the meat was given away. This brought great honor to the two girls, who were learning what it meant to be Cheyenne women. “Every part of the animal is used,” Nico explained; there is no waste. The animal was thanked for the high honor of providing its life for the sustenance of others. “I hunt and I always thank the animal for its life,” she said. “I think all hunters do that – it's instinctual; it's a powerful moment when an animal dies while you are there. “We have a long history with the Earth; our creation story speaks of the Creator asking a bird to find him some land because there was nothing but water, so the bird dove down and brought up mud. The Creator then turned that little piece of mud into land. The earth is miraculous and precious,” Nico said. She was taught about the plants that act as medicines and how you should only take what you need and leave the rest. “You never pull up sage from the roots,” she says about the sage that grows around Eagle Plumes. She uses the sage to pray herself, greeting the sun each day. There are greens and mushrooms that can be eaten in the area, and there used to be thimble berries (tiny raspberries) that grew all over the site where Eagle Plume's sits, even moss on the trees. Global warming has changed a lot of that, she said. The area in and around Rocky Mountain National Park was part of the Cheyenne's culture, providing sustenance and ceremonial sites; they came up from their land east of the foothills and north of Denver to hunt, gather berries in the canyons, and worship. Lodgepole pines from the Tahosa Valley where Eagle Plume's sits were also used. “This land around here is part of my genetic heritage,” said Nico, “it's not a mistake that I am here.” There's something about Eagle Plume's, Nico Strange Owl (Esevonenameh'ne'), and the traditions she is trying to preserve that make me stop and think. What would it be like if everyone in the world would give more than they take, if you could create family by giving gifts, and if everyone fully understood the ramifications of disrespecting the land they live on? This article was published in the November 2021 edition of HIKE ROCKY magazine.  Barb Boyer Buck is a professional writer, journalist, editor, photographer, playwright, and researcher who lives in Estes Park. Barb is the managing editor of HIKE ROCKY online magazine.

9 Comments

3/27/2023 12:46:24 pm

My husband David and I are going to visit and hopefully learn more about your culture

Reply

Nancy Hinds

8/17/2024 03:49:37 pm

As a young girl i received an arrow head as a gift from Charles Eagle Plume. It has been one of my most cherished gifts because of the kindness shown by the person who gave it to me. I am 70 yrs old now and still remember feeling so honored to be the recipient.

Reply

Dave

8/17/2024 03:58:16 pm

That's a fantastic story! Thank you for sharing it. I'm glad you enjoyed the article.

Reply

Poppy

3/15/2025 04:56:18 pm

I visited the shop many times and enjoyed speaking with your parents. They were very kind and informative in answering many of my questions. They will be missed. Good Luck with taking over the store and musuem.

Reply

RMDH

3/16/2025 05:40:48 pm

Thanks for reading and the comments!

Reply

Dave L.

3/28/2025 07:19:06 am

At the age of 6 or 7, I took received a small stone point from. Charlie. He kept varied points for giving to children in a cigar box is n one of the top drawers of a cabinet he sat in front of (pre wheelchair) and which in its lower drawers held "dead pawn". I returned many times over the decades. I became an educator and also an amateur archaeologist with a decent collection of stone and some pottery artifacts. I can date the point Charlie gave me to about 5000 bce. In later years, I also met and greatly enjoyed Dalton. We talked, not about artifacts, but about our teaching experiences, and we both laughed often during those conversations. I still have Dalton's business card. By the 80s, Charlie was no longer giving away arrowheads. He told me that convicts were flooding certain markets with reproduction stone points that were too hard to distinguish from authentic. I note that's consistent with your fine story's claims about Charlie's work toward authentic inventory.

Reply

Rocky Mountain Day Hikes

3/30/2025 11:19:06 am

Dave, Thank you so much for sharing this wonderful memory and tribute to Charlie Eagle Plume! So happy you found and enjoyed this article!

Reply

Nova McCuller

4/17/2025 02:04:42 pm

I met Charlie Eagle Plume when I was 7 years old. My father served with him in WWII. He knew him as Burkey Boy. I still remember him. He gave me a small necklace with a Turquoise cross. Very nice man.

Reply

RMDH

4/17/2025 02:33:00 pm

Thank you for sharing and for reading!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

|

© Copyright 2025 Barefoot Publications, All Rights Reserved