|

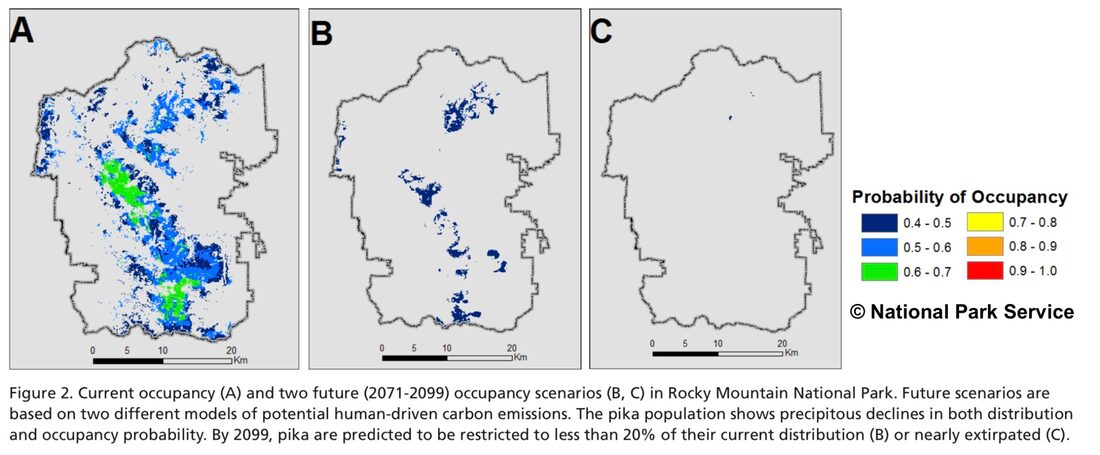

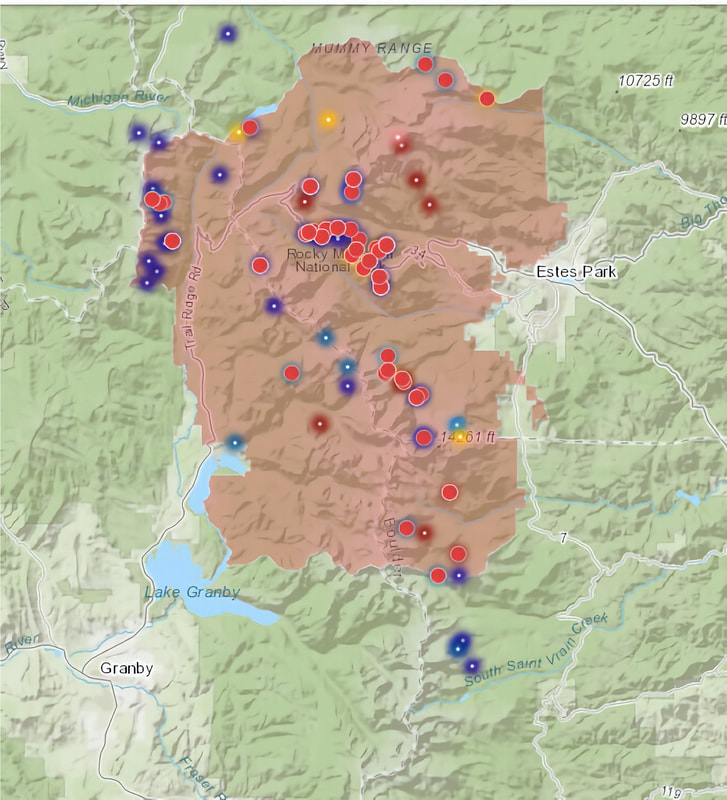

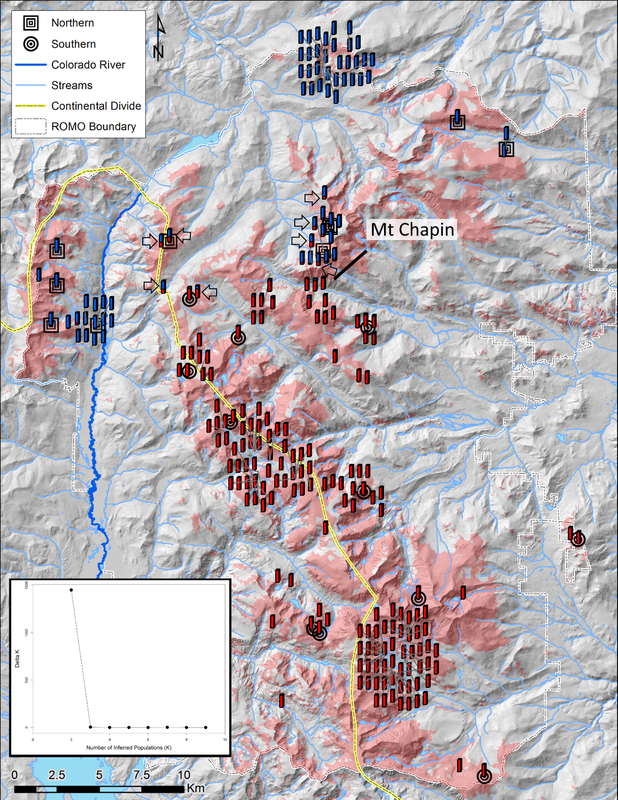

How climate change is impacting pika populations in Rocky by Barb Boyer Buck The tiny American Pika, one of the most daring and weather-hearty animals in Rocky Mountain National Park, is exhibiting declining population numbers all over Colorado due to climate change. Dr. Chris Ray, a research associate at the University of Colorado, has been studying the American Pika for several decades. In February of 2022, she and a researcher from Northern Michigan University, Hilary Rinsland, presented the most recent findings of their work and the Colorado Pika Project in the Science Behind the Scenery seminar series. The series was sponsored by Rocky and the Rocky Mountain Conservancy and ran from mid-February to mid-March of this year. “We started surveys of the American Pika in Rocky Mountain National Park ten years ago,” Dr. Ray said during her presentation in the series. “We focused on pikas because they have several traits that make them a sentinel (species) for the effects of climate on wildlife. “It’s relatively easy to determine if they are occupying any given spot. Also, they inhabit rocky areas that humans tend to avoid; so, compared to many other species they should be less affected by human activities, other than human-caused climate change.” Pikas are particularly climate-sensitive, needing access to cool climates in the summer and protection from sub-freezing temperatures during the winter time, she explained. The American Pika, Ochotona princeps, is native to Rocky Mountain National Park, and other high- elevation locations in the state. They occupy talus, or scree-slope, habitats above treeline. Busily gathering greens all summer, pikas are the tiny animals in the rabbit family who are often heard chirping communications to their compatriots. Pikas create hay piles upon which they feed all winter, while nestled underground under rocks and a thick layer of snow. They are an incredibly charismatic species, with big ears (similar to a famous cartoon mouse), and they need our help. “By mid-century, population would dip below 50% of occupancy and that population would start to contract dramatically under business as usual,’ (or, no changes in greenhouse emissions),” Dr. Ray said. “The changes in population are based on predictions of the above-surface climate, but pikas spend a lot of time under the surface. So, we are monitoring all their micro-habitats, too, hopefully to support our understanding of flora and fauna changes in relation to pikas,” said Dr. Ray. “We couldn't do all this monitoring without the help of the community,” she said, citing the “impressive community science project, the Colorado Pika Project.” This project was created by the Denver Zoo and Rocky Mountain Wild, which manage the volunteer efforts of monitoring the American Pika not only in Rocky, but also along the Front Range and in the White River National Forest. “In 2021, 56 volunteers surveyed 72 randomly-selected plots,” said Dr. Ray. “Twenty-four plots are surveyed every year and additional plots are surveyed in even or odd years so that more of the Park can be surveyed with the limited pool of volunteers. “The plots are small but that’s important because it takes a while to survey the 3D plot for pika science.” Volunteers look for pikas, listen for pika calls, and look for pika sign, such as fresh/old hay piles and fresh/old scat. Other observations taken include signs of other species such as ptarmigan, marmots, and weasels. The compilation of results is mapped above (a more detailed, ARC/GIS interactive map can be found here.) The red dots are sites where no pika sign was found, the yellow are where old sign was found and the cooler colors indicate where pikas or current pika sign was found. “Occupancy is declining in different kinds of models with a rise in temperature across the landscape,” said Dr. Ray. Areas of higher concentration of pikas were found where the crevice-depth was deeper, indicating “where pikas have more ability to get away from the climate,” she said. Recently, two sub-species of the American Pika were found in Rocky, explained Hilary Rinsland. She was lucky enough to conduct further research in the Park when it was closed to visitors, during COVID. She collected blood and scat samples to screen for disease and parasites, which may also be impacting pika populations. The two genetic clusters and assignment to either the north (blue) or south (red) clusters are indicated on the map below. Darker circles indicate multiple samples from that locality. “The modeling suggests that the southern sub-species was going to be particularly vulnerable to habitat loss,” said Hilary. “Pikas are poor dispersers and cold sensitive, it may become impossible to re-colonize.” “Knowing that, and thinking about the subspecies, we wanted to do a study” that incorporates all these factors, Hilary continued. “Pikas are moving to higher elevations as temperatures are getting warmer.” She explained that the protocols used in her studies were the same one as the Colorado Pika Project were using, to ensure a seamless interface when comparing the results of monitoring. You, too, can help with the American Pika studies in Rocky by signing up as a monitoring volunteer with the Colorado Pika Project. You can find detailed information on the opportunities available in Rocky here: https://pikapartners.org/rmnp-resources/ We also need to do our part to combat climate change in our own habitats, if for nothing else than the plight of the American Pika. This wonderful creature deserves to keep its home forever, in Rocky Mountain National Park.  Barb Boyer Buck is the managing editor of HIKE ROCKY magazine. She is a professional journalist, photographer, editor and playwright. In 2014 and 2015, she wrote and directed two original plays about Estes Park and Rocky Mountain National Park, to honor the Park’s 100th anniversary. Barb lives in Estes Park with her cat, Percy.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

|

© Copyright 2025 Barefoot Publications, All Rights Reserved