|

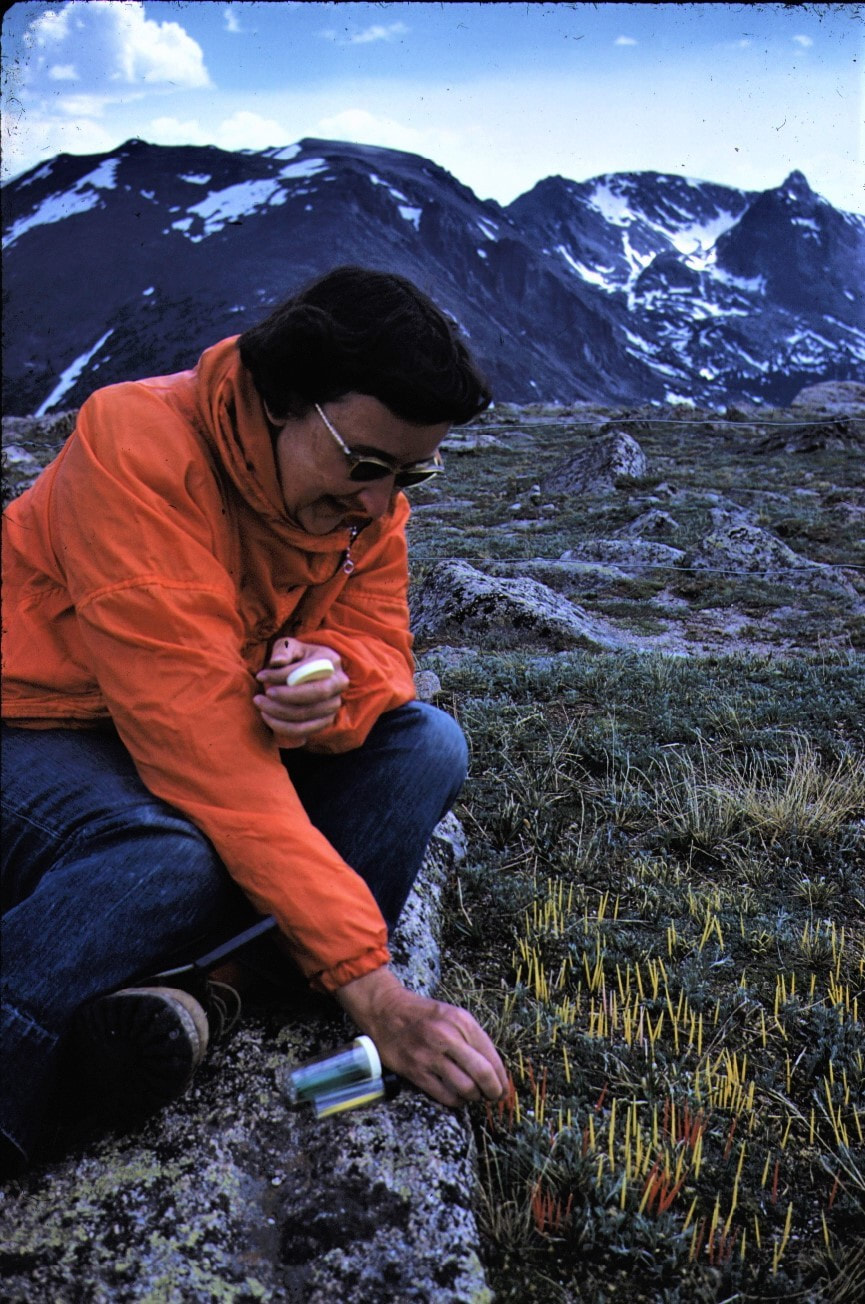

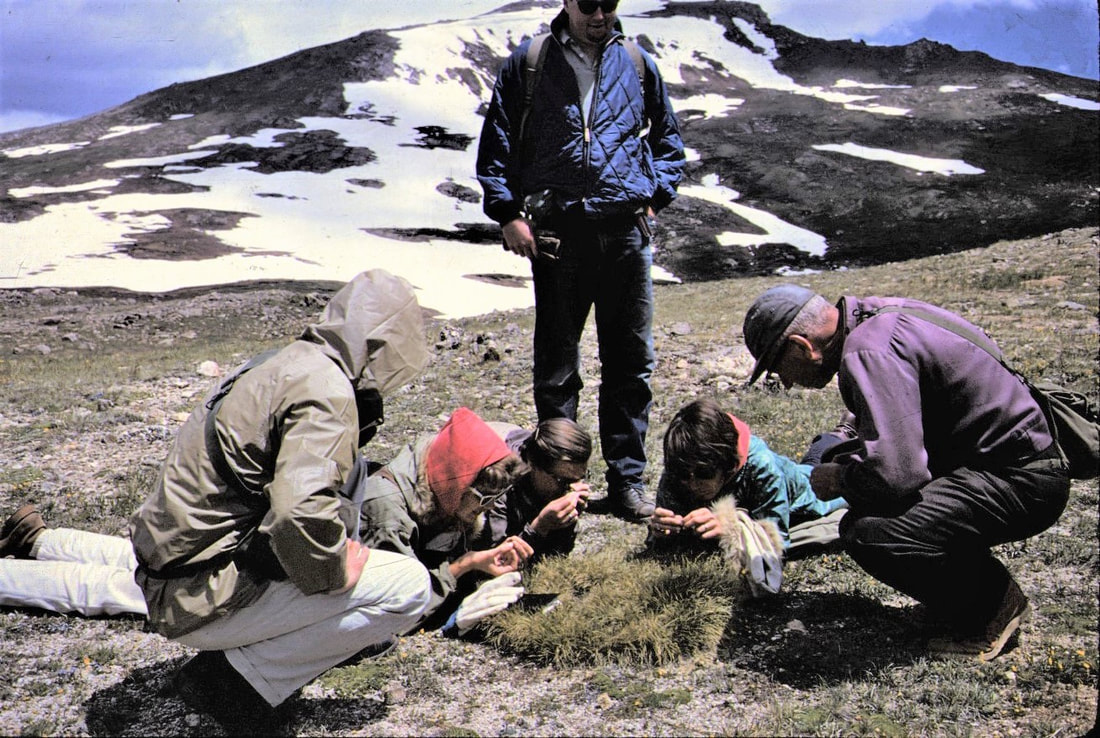

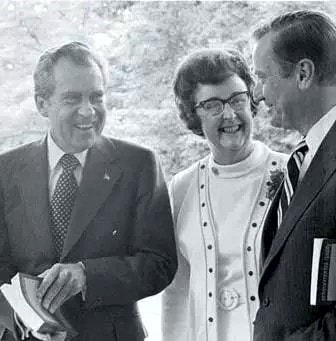

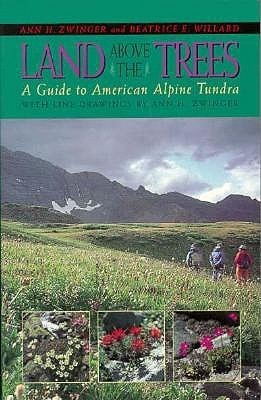

It is illegal to walk on the tundra in Rocky Mountain National Park at Fall River Pass, Gore Range, Rock Cut, Lava Cliffs and Forest Canyon Overlook. For reasons which will be explained, concentrated visitor use atthese areas poses a proven threat to the delicate tundra. HOWEVER, other areas of the alpine tundra, which is one-third of the Park's terrain, can be traversed upon; albeit, very lightly. Walking is not the preferred way to study this ecosystem up close. “Belly Science” – first developed by Bettie Willard – puts you on the tundra face down, spreading your weight across plants that have survived the harshest of climates for hundreds of years. The ground is surprisingly soft and supple, even furry in places where fine white hairs grow over leaves and petals, protecting each tiny plant from hurricane- force winds and near-freezing overnight temperatures. Fragrant, floral, clean and airy: the smells of the tundra are reserved for those who have the audacity to stick their noses into it. (see Rocky Mountain National Park’s policy on tundra use) This is a world where the smallest of organisms create a community of symbiotic relationships, each plant working with each pollinator to help feed its neighbors and expand vegetation above treeline, a world where roots run deep and plants stay short, with impossibly- bright blooms spreading out to hug the horizon, all the way up to the vertical end of the world. Respecting this world is paramount and understanding its legacy is just as profound. Bettie Willard's National Park work Bettie Willard always dreamed of being a National Park Service ranger, especially after she attended the Yosemite Field School in the summer of 1948. For that entire summer, she and other attendees lived in tents and worked in the wilds of Yosemite National Park, studying nature up close. Graduates from the field school – 16 men and four women – were then interviewed by the National Park Service, but Bettie's dream of being a ranger was dashed: “Don't you know? We don't hire women for those positions,” she was told. It didn't matter that she had just graduated from Stanford University with a degree in biological sciences or that she already had a lifetime of experience guiding through the wilds near Mammoth Lakes, California, where she spent summers with her parents. It only mattered that she was female. Willard dealt with mid-Century norms for women throughout the rest of her life but this environmentalist was not daunted. She had made an influential friend: Dorr Yeager, Rocky Mountain National Park's first naturalist and author of the “Bob Flame, RMNP Ranger” novels. Over the next several years, he asked around and found only four National Parks that were willing to hire women; one of these, Lava Beds National Monument (est. 1925), finally hired her as a ranger for the summer of 1952. The following summer, she was a ranger at Crater Lake National Park (est. 1902). When asked later in life how she got along as the only female ranger in those Parks at that time, she said that she did a lot of observation at first, finding out which rangers worked in which department or niche. Willard filled neglected niches, thus preventing stepped- on toes (and egos) of the more established, male rangers. She prided herself on complementing – not competing with – what the other rangers were doing. Between her undergraduate studies and this life goal achieved, Willard attended UC Berkeley to become a teacher. She taught in Salinas, then Oakland and finally general studies at Tulelake High School, located in California near the Oregon border. It was considered a rural school and eligible for the newly formed Ford Foundation educational grants. In 1954, she was awarded a $4,600 scholarship which “was enough for her to go to Europe for 14 months to study vegetation on the high mountains. She wanted to study the vegetation in the Alps, in Scandinavia and other places in Europe,” explained Leanne Benton, co-instructor for the Rocky Mountain Conservancy's “Bettie” Course: “Tundra Pioneer: the life and legacy of Bettie Willard,” held on July 20. Benton is a long-time Rocky Mountain National Park volunteer and taught this course with Cheri Yost, the current Park Planner for Rocky. While in Europe, Willard attended a conference of 2,000 international botanists in Paris and made valuable connections which led to several field trips in Switzerland to study alpine plants. “She also met a woman, Ruth Ashton Nelson, who was a Colorado botanist and had already published a book on the plants of the Rocky Mountain National Park,” Benton said. By the time Bettie was finished with her European studies and work, she knew she wanted to go to grad school and study American alpine plants, specifically to compare those with the plants she had studied in Europe. But first Willard had to fulfil the requirements of the scholarship by teaching two more years at Tulelake. In 1957, she enrolled in the University of Colorado at Boulder to study ecology. “Ecology really came into its own in the late 1890s and women were getting ecology degrees since the 1910s,” Cheri Yost explained. “But most women ecologists were either working with their more famous husbands, like Edith Clements, or they were teachers. They really weren't doing their own independent research.” But by the late 1950s Willard was doing just that, under the instruction of noted arctic and alpine ecologist John W. Marr. Willard wanted to study “plant sociology” (like she did in Europe) on the alpine tundra in Rocky. She established a plot at Rock Cut in 1958 that was 10 square meters large (current pipe fencing at Rock Cut includes her original plot). The same trail that she used through this area can still be seen, standing as a testament to the long recovery time for disturbed tundra. A second plot was established at the newly-built Forest Canyon Overlook. Her studies at several spots on Rocky's tundra led to the completion of her master's and then her doctorate, from the University of Colorado. “What she was noticing was that visitor use was having a huge impact on the tundra,” Yost said. Willard needed to convince Park managers that visitors were having an impact on this delicate area and that something had to be done about it. She thought the trails on the tundra should be paved and hardened, “if you pave a trail, people will stay on them,” was her argument. Next, she wanted Park managers to “stop the craziness in the backcountry,” because there were no rules about camping in the backcountry in Rocky. And finally, Willard wanted people to become stewards of the tundra through education and experience. She accomplished these goals by utilizing the skills, hard work and diplomacy that she had always applied working in the heretofore “man's world” of the National Parks. Visitor impact was proven through vast data sets – collected by Willard and others - that tracked alpine environments. Mission 66 (which was launched in the mid-1950s) provided the infrastructure funds to pave the areas she recommended, and her experience with backcountry “craziness” in her research both above and below treeline led to the establishment of backcountry camping permits in the early 1970s. Willard started teaching the first field seminar program in Rocky Mountain National Park, through the Rocky Mountain Nature Association (now the RM Conservancy). “She taught the alpine field seminar for many, many years in the Park,” said Yost. Willard was also instrumental in getting alpine rangers in Rocky to teach the public about the tundra and in the placement of signage and educational displays in the Alpine Visitor Center and other places. For 40 years, Willard came back to study her alpine plots every summer in Rocky, funded in part by the Department of Defense (since the country was still at war in various arenas). “She took photos of her plots, put toothpicks down to mark the individual plants, and tracked those plants for the entire time she worked in Rocky,” Yost said. Today, Jackson Maldonado, Alpine Community Science Intern, is continuing Bettie's work in much the same way. This summer was the kick-off of a continuing community science project that will encompass two programs: one with trained volunteers doing surveys at Willard's original plots and the other program designed for community members. It will teach them about climate change effects on the tundra, and the phenology (or life-cycle) of tundra plants and include an excursion onto the tundra to identify its wildflowers. “If we can get a solid data set that builds off of what Bettie started, we can really track the impacts climate change is having on the tundra,” Maldonado said. He spent much of the summer working with Park employees to create the parameters, logistics and study scope of the project, which will kick off its first year of serious study in the summer of 2024. Bettie's "experiments in ecology" But Bettie Willard's story doesn’t end with her important conservation work in Rocky. She wrote Land Above the Trees: Guide to American Alpine Tundra with Ann Zwinger in 1971. “This book was instrumental while I was learning about the tundra as an RMNP ranger,” said Leanne Benton. Moss campion, a cushion plant, is one of the “champions” of the tundra, Benton said, growing only about ½ inch by the time it's five years old. “It doesn't really start to bloom unless it's about 10 years old and by the time it's 20-25 years old it's about 7 inches wide and blooming profusely. “Think about what a grinding footstep can do to a plant like this,” Benton said. After Willard achieved her doctorate, she stayed in Boulder and helped to found the Thorne Ecological Institute. In 1965, she became its Executive Director, in 1967, she was its vice president; and, in 1970, president. “Thorne's mission was to help people understand the relationships in the environment and develop a personal concern for the Earth,” explained Cheri Yost. “While Willard was at Thorne, it put her at the forefront of many environmental partnerships.” Willard went on to form and/or serve with numerous environmental organizations throughout the state, excelling at collaboration. “In 1966, she created what she called 'the experiment in ecology,' ” explained Yost. “She really believed that all of these conversations were a three-legged stool: engineering, economics and the environment. If you could not get these three concerns to talk to each other, you are not going to be successful stewards of health and society.” Working with the mining industry along with environmental concerns in Colorado, Willard created “a safe space to work out differences so meaningful and lasting agreements could be made,” Yost explained. “We fostered abundant measures of openness, objectivity, willingness to tell all, an ability to listen and believe but to question until Truth comes forward,” Willard said of this time in her life. Working for the Federal Government In 1969, Congress passed the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), which codified Willard's “experiment in ecology,” on a national level. Its mission was to bring every new environmental policy in front of everyone who would be affected by it. The next year, President Richard M. Nixon appointed Willard to the President's Council of Environmental Quality (CEQ). She was the first woman to serve on this council, which existed to educate everybody in the country on NEPA. “Most of the environmental laws on the books today were put in under the Nixon Administration,” explained Yost. Willard received many letters of congratulations for her service with the federal government, but nearly every one of them contained some back-handed compliments, essentially: “pretty good – for a woman.” For the rest of her life, Willard went on to champion common-sense environmental laws in Colorado and nationwide. For example, said Benton, there were several things that Willard did to help mitigate the environmental issues with the Alaskan Pipeline during its NEPA process. “She made about 15 trips up to Alaska during that time to look at the route planned for the pipeline and was instrumental in getting the pipeline raised above areas of permafrost (so it wouldn't melt) – and raised high enough to not interfere with caribou migration.” Willard was not against development. “She worked for Nixon, she was a Republican,” Yost said. “She was the head of the Colorado Olympic Committee in 1970 when Denver was awarded the 1976 Winter Olympics. She didn't have any concerns about the Olympics itself, she had a problem with the necessary, uncontrolled building that was going to happen next to it.” Ultimately, voters in Colorado voted against holding the 1976 Winter Olympics in the Colorado Rockies, making it the only state to ever refuse the offer. Bettie returns to Colorado to educate on environmental issues in the state Bettie Willard returned to Boulder after the change of administration and after a few years, “she was approached by the Colorado School of Mines, one of the foremost mining schools internationally, to set up a department of environmental sciences, looking at how to mitigate the effects of mining,” Benton explained. When she was interviewing for the job, she asked the president of the board: 'How do you feel about working with a woman?' She accepted, but only after being assured that anyone exhibiting chauvinistic behaviors would not be tolerated at the school. She developed the brand-new department and created 28 classes, many of which she taught herself. Thirty- two students graduated with the Minor degree she designed, but still, she didn't feel equal to her fellow professors. “She felt some type of discrimination,” Benton said. In 1982, she took a leave of absence: two years without pay. Nevertheless, she traveled, cross-country skied, taught, and wrote books (many of which are some of Benton's most treasured possessions). When it came time to return to the School of Mines, she just didn't want to and “resigned” in 1984. For the rest of her life until she was no longer able, Bettie Willard wrote books, taught, served on groups and committees and taught seminars. “She taught seminars here (for the Rocky Mountain Conservancy) until 1996,” said Benton. “I was able to take a course from her in 1995,” Benton recalled. This experience really cemented Benton's commitment to Rocky. “She was a very gifted teacher,” Benton said. Bettie Willard passed away from Alzheimer's disease in 2003. You can continue Bettie's legacy at Rocky! Jackson Maldonado is looking for some people to practice Belly Science with him next summer, through his Alpine Community Science projects. You can reach him with questions at [email protected]) Like Willard, Maldonado dreams of working for the National Park Service after he graduates. “I would love to make Parks more accessible, everyone deserves to be in green space, to experience nature, safely.” He admires Bettie Willard very much. “The work that she accomplished locally, regionally and nationally positively impacted so many people and the environment.” (Maldonado's views do not necessarily reflect the goals and ideas of the National Park Service.) Like Bettie, Leanne Benton grew up in California. In college, she took a summer Park Ranger job at Rocky; “It was a life-changing summer – I loved the work and the Park. For four more summers I worked as a seasonal Park Ranger on the west side. I met my husband one of those summers who was also a Park Ranger.” After years of working as a full-time Park Ranger for several NPS units, Benton returned to Rocky to manage the Alpine Visitor Center for eleven years. She continues to volunteer with Rocky.  “In Land Above the Trees (1972), Bettie Willard and Ann Zwinger brought together most of what was known about alpine tundra in the U.S., including Bettie's research, and presented it in a book that was understandable for a wide audience,” Benton said. “The book was a huge success. The information so poetically presented in the book illuminated the fascinating adaptations of the plants and animals for survival in the alpine world. Land Above the Trees was THE BOOK that all the park rangers read to learn about alpine ecology so we could effectively communicate with the public. This book continues to be relevant today. The results of Bettie's research and recommendations also laid the foundation for how Park Managers protect the park's tundra, while also allowing public enjoyment of the tundra. Bettie also recommended the importance of education in protecting the tundra.” Benton wants you to remember that while traveling on the tundra, move like a herd of elk, not a line of people. Step on stones or gravel where possible and if there is a trail, use it. Cheri Yost has spent most of her NPS career translating science, which is how she was introduced to the remarkable legacy of Dr. Willard. She is currently the Park Planner.  Barb Boyer Buck is the managing editor of HIKE ROCKY magazine. She is a professional journalist, photographer, editor and playwright. In 2014 and 2015, she wrote and directed two original plays about Isabella Bird and Rocky Mountain National Park, to honor the Park’s 100th anniversary. Barb lives in Estes Park with her cat, Percy.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

|

© Copyright 2025 Barefoot Publications, All Rights Reserved