|

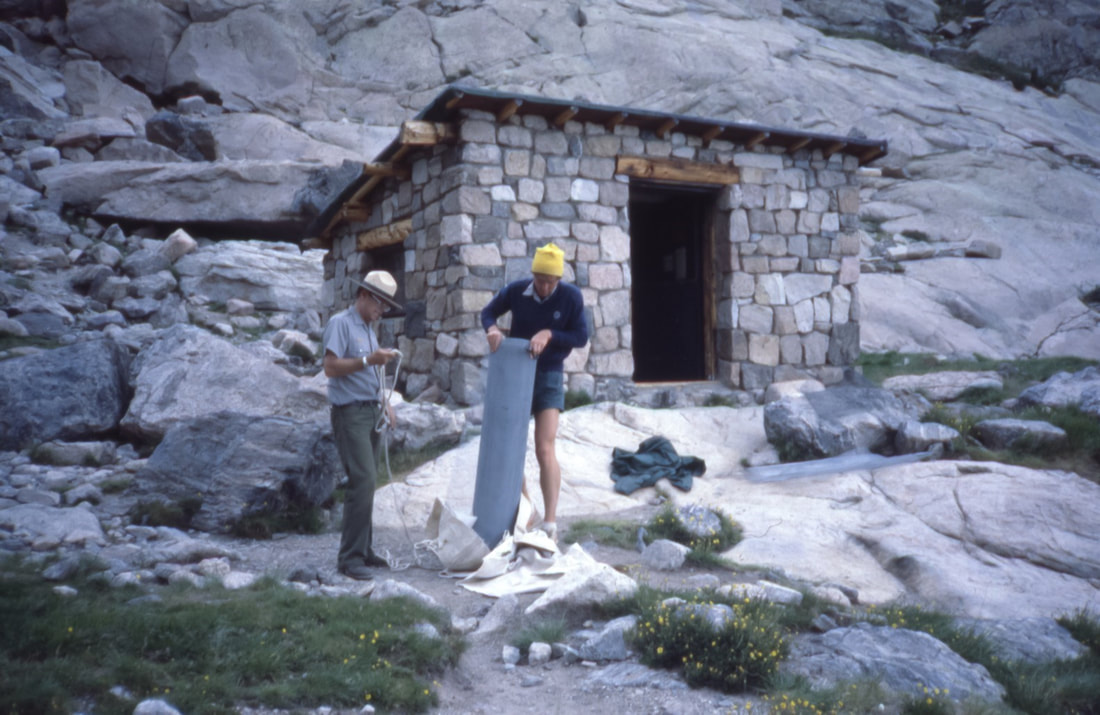

memoir and photos by Chris Reveley, Longs Peak Ranger 1979-1981  Bert McClaren and Chris Reveley unloading supplies in front of the (now-gone) Chasm Meadow cabin. The structure was used for many years as a cache for rescue gear; there were ropes, a litter and climbing hardware. There were also four bunks and old army surplus sleeping bags, in case rescuers had to spend the night. Climbing rocks, ice and big snowy mountains is dangerous. Sometimes people get hurt and occasionally they die. The job of search and rescue (SAR) first-responders is to deliver to the injured an appropriate level of care as efficiently and safely as possible without making matters worse. In the case of fatalities, body recovery is pursued whenever and wherever possible as long as the risks to SAR personnel are minimal. As in most of the U.S., SAR services in RMNP are available anytime, day or night, in all seasons. Those who do this work may be trained specialists employed by the Park, highly skilled individuals from the community who are called upon as-needed or qualified volunteers. They may reach the needy on foot, in vehicles, in boats or aircraft. In RMNP, SAR has taken place primarily on higher mountain terrain, though rescues and body recoveries in and around fast-moving water at lower elevations also occur. At times, cooperation with other SAR groups and the military has proved very valuable. For more than a century, Rocky has been fortunate to have a pool of highly skilled rock climbers and mountaineers close at hand, within the population of local instructors and guides. Recognized as valuable assets by Park managers, these individuals have frequently been called upon to assist with or sometimes direct SAR missions on highly technical terrain. Some of these experienced alpinists have found full-time employment and long-term careers with the NPS in Parks with traditionally high levels of technical climbing activity: Denali, Mt. Rainer, Yosemite, Teton and RMNP. This was the path that led me to the Longs Peak Ranger Station in 1978. Mountaineering hazards come in two primary flavors: objective and subjective. Objectively, mountains present variable surface conditions and atmospheric changes that when combined, can contribute to life- threatening situations. What's commonly called “bad luck” is often a feature of the predictably unpredictable and unstable mountain environment. Subjectively, climbers bring to the mountains various levels of experience, skill and judgement. With consideration of all possible variables and realistic assessment of a party's strengths, weaknesses and goals, climbing trips tend to turn out well. Poor planning, bad decisions and inadequate preparation are common contributors to bad outcomes. In the spirit of boldly going where others have not, mountaineers sometimes press on in the face of adversity and exhaustion to accomplish great feats. Our heroic dreams are egged-on by the human (often, male) endocrine system to lead us down harrowing, narrowing dark holes from which adrenaline and testosterone will not rescue the foolish. Just as aircraft disasters can sometimes be traced to a series of mis- judgements and bad decisions, analyses of mountaineering disasters often reveal a trail of errors from which we can all learn valuable lessons. Successful rescues of the injured are sometimes the product of one person's quick, decisive action. More often, they result from the work of a well-coordinated team with wise, experienced leadership and skilled, hard-working foot soldiers. One early summer morning in the late 1970s, I was visiting with campers at the Boulderfield site on Longs Peak when I received a radio call: a Park visitor hiking in the Chasm Lake Cirque had reported calls for help from “somewhere on the East Face”. I went over the ridge between Mount Lady Washington and Longs Peak, past the Camel formation, and descended into the Cirque. Shouting was actually coming from the Broadway ledge at the base of the Diamond on Longs Peak, one of the largest high-altitude walls in the U.S. and a popular destination for experienced rock climbers. I climbed the North Chimney on the Lower East Face and reached Broadway about 30 minutes after receiving the radio call. A climber had fallen from the poorly- protected, horizontally-traversing section of the so- called “casual route,” sustaining blunt trauma to various body parts in the long, pendulum-like fall. He was alert, moving all limbs and seemed fully oriented to the situation. Most worrisome, however, was his report of intense back pain between his shoulders. A quick exam revealed a very red, very swollen, tender-to-touch area over his mid-thoracic vertebrae. Back in radio-contact with the dispatch office, I asked them to mobilize the Park rescue team. Gathering rescue team members and necessary equipment was accomplished quickly at Park headquarters. The first members of the rescue group began to appear at the east end of Chasm Lake a few hours later. Leaving the injured climber warm, fed and watered in the company of his partner, I climbed back down the North Chimney and joined the team to help establish a line of fixed ropes up to Broadway. This allowed the dozen or so members of the team to ascend safely, carrying packs filled with ropes, climbing anchors and the two-piece, metal litter in which the injured climber would be lowered several hundred feet down the steep lower East Face. They also carried bivouac gear in case we had to spend the night. The day went by quickly. We established a safety zone for all the rescuers and built a multi- component, equalized anchor for the litter evacuation. The climber was placed in the litter and positioned without pressure on the injury. One of the Park's most experienced paramedics, Frank Fiala, secured himself to the litter's frame at the climber's head. I took up a position at the feet. Shoulder-mounted radios allowed us to communicate with those managing our descent. Mostly, we requested slack in either the head or foot line in order to keep the litter in a slightly head-up/foot- down orientation. The lowering took more than an hour. On the way down I remember feeling pretty good about the whole situation: On the litter, all three of our lives depended on expert management above. Charlie Logan, an experienced, long-time Ranger was in charge on Broadway; very comforting. The weather was holding, the injured climber was comfortable and not reporting worsening symptoms and we learned that Bob Greeno, a legendary helicopter pilot would be flying in for the rescue. Rumor had it that Bob had taken part in the “Helicopter Olympics” in Russia. None of us knew exactly what that meant but it sounded impressive. In 1967, he had rescued five survivors of an airplane crash, high on the slopes of Mount Sherman in Colorado. The feat was described by FAA officials as “…the most daring and spectacular mountain-top 'save' in aviation history.” Several of us had worked with Greeno and we valued his great skill and excellent judgement. Winds in the Chasm Cirque were constantly variable and tricky. The helicopter's only possible landing zone (LZ) was a large, flat boulder just below the snowfield under the lower East Face. A collective expression of joy and relief went up from the assembled rescue team when we heard that Bob was on his way. But darkness was approaching and we started to worry. It felt like time was of the essence with the climber's serious injury. We feared that bleeding or the swelling of soft tissue around the damaged vertebrae might impinge on his spinal cord and lead to permanent damage. At first, the little Alouette Lama helicopter sounded like a bumble bee as it turned west and started up the valley far below Chasm Lake. Within minutes, Greeno was hovering above us, surveying the LZ. The “large, flat boulder” suddenly looked smaller and a little tilted. If he couldn't execute the landing safely, he would have to leave, no negotiating. The helicopter danced directly above us as Bob tested the winds and viewed the LZ from several different angles. We were all hidden beneath the boulder's edge, well protected (in case things went very bad) but ready to approach the aircraft once he landed and gave us the thumbs up. Then, rather suddenly, down he came, placing both of the helicopter's skids perfectly on the exact center of the boulder. I peeked up over the edge. He nodded slowly and waved us in. The whole loading operation took about one minute. The litter with its precious cargo barely fit in the small aircraft. We stepped away, toward the helicopter's nose where Bob could see us and then…he was gone. Twenty minutes later Bob delivered the injured climber to a Denver hospital. Back in the Chasm Cirque there were cheers, tears and hugs. It had been a long exhausting day, physically and emotionally, and we all fell asleep easily amidst the rocks. Somewhat rested, we hiked out the next morning at first light. It was the next summer that the injured climber returned to the Longs Peak Ranger Station to thank us. He was fully recovered. Out of respect for the families of those who did not survive accidents, I won't speak about specific incidents here. I can write about the effects those searches and body recoveries had on me. Like many baby boomers raised in the middle-class suburbs of American cities, I had little first-hand experience with death. When we signed up for SAR work around Longs Peak, no one talked about the high probability that we would be searching for and retrieving severely damaged human bodies as a routine part of the job. I approached every response to a likely fatality with a degree of hesitation and an uncomfortable mixture of purpose, fear and anger. Indeed, this was part of a job I had accepted and I was duty-bound to proceed. I was reminded and frightened by how easily a moment of inattention or the choosing of a wrong path could lead to the end of a life in this environment where I moved so easily, perhaps a little too comfortable with the ever-present hazards. I was angered by those instances where the death was a result of negligence, ignorance and poor judgement on the part of the individual or those who were relied upon as leaders. And, I was stunned, thinking about the lifelong psychological and emotional pain the families would endure. I remember details of every one of those body recoveries and as I've passed by some of those locations in the last 40 years, I paused each time for a moment of sad reverence. For me, the deaths of children were always the most difficult to confront and process while going about our work.  Chris Reveley has spent 50 years climbing and doing endurance sports; and, thirty years learning and practicing medicine. “Now I’m a Happy House Husband with hobbies,” he said. The publication of this article from the April/May 2023 issue of HIKE ROCKY magazine was made possible by Inkwell and Brew and MacDonald Book Shop

The Mad Moose and Xplorer Maps

6 Comments

Don Sellers

6/29/2023 10:25:51 am

Amazing story, Chris! Thank you for sharing this very interesting life story.

Reply

Chris Reveley

8/13/2023 08:20:22 am

Hi Don,

Reply

Janet Greeno Sund

11/21/2023 12:28:20 pm

Dear Mr Reveley. Thank you for writing this article. What a gift of service to others your and your comrades have blessed many with even in the face of your own potential peril.

Reply

8/9/2023 03:10:50 pm

Chris...always remember you,John and I running crazy trails or slopes. I still run ( slow) hike and bike. Still busy at work ( see website). My son,Brennan, is a runner ( went to CU on scholarship) and now runs like we used to but he's a notch above. He is in Colorado for a little longer and today's run was Mt.Columbia. I wish I could have had him meet you because he has heard many stories about the legendary John Link and Chris Reveley. Maybe this could happen at some point.

Reply

Chris Reveley

8/13/2023 08:16:25 am

Jerry

Reply

Paul Magnifico

9/16/2025 04:07:30 pm

Thought of you yesterday while passing Longs peak and again today while fueling up in Sheridan. Read once that you lived there. An attempt to locate you led me to several gap-filling articles. Would love to reconnect.... Paul

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

|

© Copyright 2025 Barefoot Publications, All Rights Reserved