|

story and photos by Scott Rashid, director of the Colorado Avian Research and Rehabilitation Institute For many of us, the term “snowbirds” has two meanings. One is the older folks that live in Colorado for the summer and head south to winter in Arizona, Texas, or Florida. The other meaning is the birds that winter in Colorado. Snowbirds (the avian kind) that are found in the mountains can be different species than those found in the foothills and plains. For example, each winter, Clark's Nutcrackers, Pine Grosbeaks, and brown- capped, black and Gray-crowned Rosy-finches move from the alpine tundra of Rocky and sub-alpine and to winter in and around Estes Park, Aspen, Vail, and other mountain towns. Other mountain species including Steller's Jays, Mountain Chickadees, Brown Creepers, Red-breasted Nuthatches, Cassin's Finches, and Pine Siskins may simply move from the mountains which at roughly 7,000-9,000 feet and move to winter at about 5,000 feet. There are species that come down from the north to spend the winter in Colorado every year. These include Rough-legged Hawks, Herring Gulls, Lesser Black- backed Gulls, Ring-billed Gulls, Tree Sparrows, Northern Shrikes, Harris's Sparrows, and Lapland Longspurs. Other species including Evening Grosbeaks, Bohemian Waxwings, Snow Buntings, Red Crossbills, Common Redpolls, Purple Finches, and Snowy Owls, are seen only during some winters. When these species are seen they are frequently in large numbers, in multiple locations throughout the state. When those species are seen in large numbers, it is often considered an eruption. Eruptions occur due to a reduction in resources on their nesting grounds, forcing the birds to move to areas that will sustain them throughout the winter. A few years ago, there was an eruption of Common Redpolls in Colorado. These tiny finches (about the size of a goldfinch or Pine Siskin) came down from the far north and spent the winter here. It seemed like everyone who had a bird feeder was seeing redpolls. That was a wonderful sight. The interesting part of these eruption years is that it is seldom, if ever an eruption of more then a single species. This year happens to be an exception to the rule as Bohemian Waxwings, Cassin's Finches and Evening Grosbeaks are being seen in large numbers. The Bohemian Waxwings (the larger cousin to the Cedar Waxwings, which are seen in Colorado in the spring and summer) are being seen in areas where fruit bearing trees and shrubs have high concentrations of apples, and berries that the birds are feasting upon. There are areas where you can find well over 100 birds in a flock. The birds feel safer in large numbers as it is easier for them to stay protected from predators and find enough food to feed the members of the flock, as there is always a bird or two searching for the next resource heavy location. Evening Grosbeaks and Cassin's Finches are also being seen in large numbers this winter. These finches are being seen at bird feeders feasting upon sunflower seeds. They are easily attracted to your yard if you have large platform feeders filled with sunflower seed where the birds can feed in large numbers. Finches including Evening Grosbeaks and Cassin's Finches feel safer in large numbers and are being seen in flocks of 60 and 70 individuals at a time. As spring approaches (March and April) the waxwings will move north to nest in Canada, Some of the Evening Grosbeaks and Cassin's Finches may remain in Colorado to nest, but many of them will move north into Wyoming and Montana to nest. As spring approaches, many of our summer residents, both avian and human will begin returning to Estes Park to spend the summer.  Artist, researcher, bird rehabilitator, author, and director of a nonprofit are only a few things that describe Scott Rashid. Scott has been painting, illustrating and writing about birds for over 30 years. In 2011, Scott created the Colorado Avian Research and Rehabilitation Institute in Estes Park. In 2019, Scott located and documented the first Boreal Owl nest in the history of Rocky Mountain National Park in Colorado. Scott has written and published five books and several papers on a variety of avian species. More information is available on his website: http://www.carriep.org/ The piece of original content was made possible by New Roots Real Estate and the Country Market of Estes Park.

0 Comments

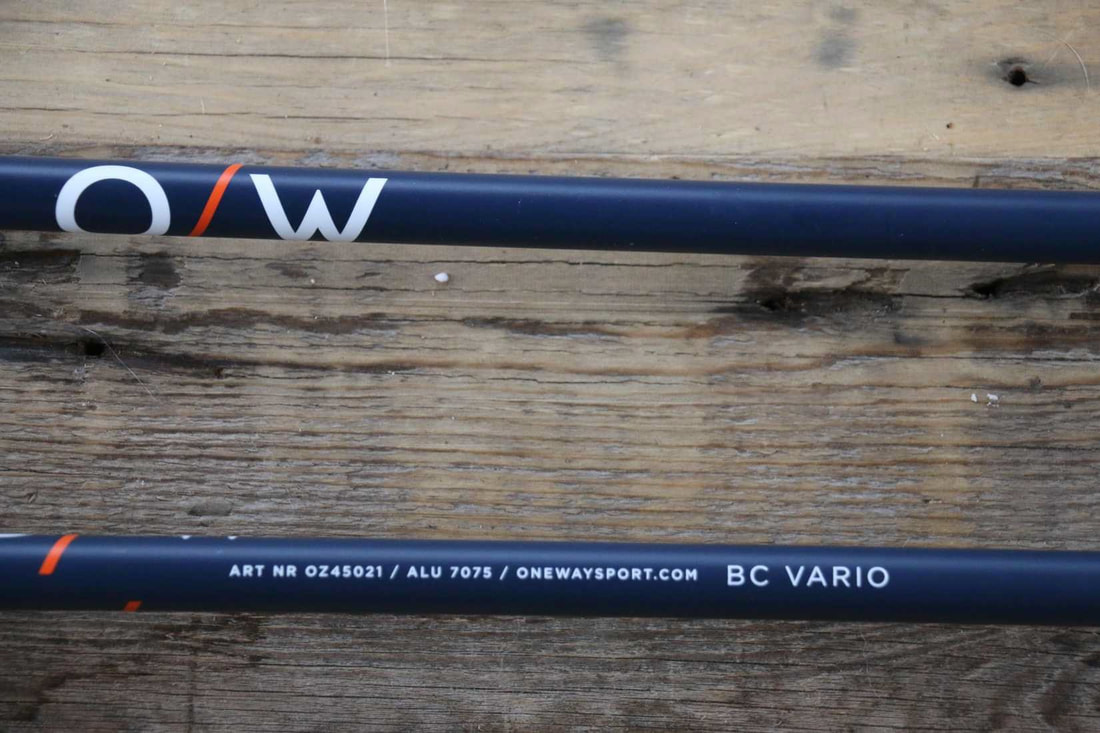

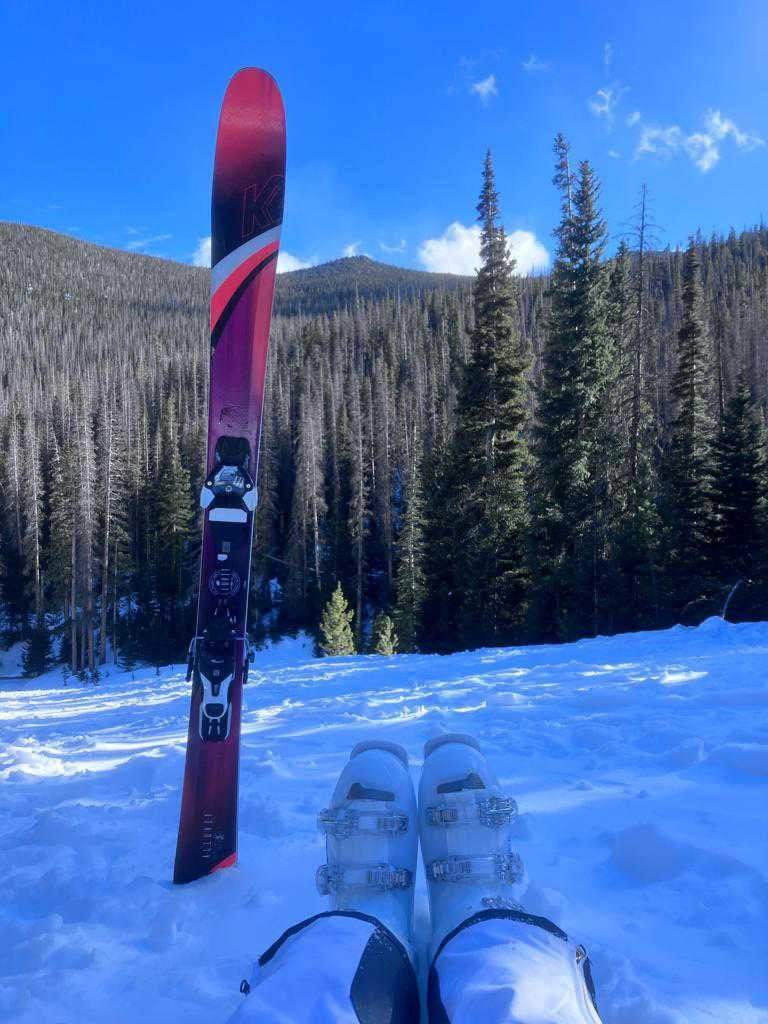

A note from the editor: HIKE ROCKY magazine receives no compensation from the brands reviewed by Murray in this piece story and video by Murray Selleck, HIKE ROCKY magazine's gear reviewer We all have a favorite piece of winter gear. Whether it's a base layer for warmth, a pair of skis that makes one feel like a Norse god or a perfectly-fitting pair of lucky socks, these favorites have the ability to make a winter outing sublime. Over the years, my favorites have evolved just as design, materials, and manufacturing have evolved. I’ve worn out gear that I have reluctantly replaced. I have also given away perfectly good pieces of equipment or clothing that just didn't fit right or suit my skiing preferences. We all have a favorite piece of winter gear. Whether it's a base layer for warmth, a pair of skis that makes one feel like a Norse god or a perfectly-fitting pair of lucky socks, these favorites have the ability to make a winter outing sublime. This selection of equipment and clothing has become essential to my winter backcountry days. I don’t leave home without them! Primus Preppen Vacuum Jug and Vacuum Bottle Cold winter backcountry days when the winds are up and the temperatures down are enhanced with tummy- warming food and drink. I’ve taken to carrying the Primus Preppen Vacuum Jug and their Vacuum Bottle with me on my backcountry ski days. I fill the jug with soup and the bottle with either coffee, tea or hot chocolate. A quick pause from breaking trail and making turns to fuel up with warm food and drink not only provides a boost in energy but a boost in morale, as well! Dark, cold, wintery days suddenly feel not less challenging with tasty comfort food and a hot drink fueling one up. The Primus Preppen Jug and Vacuum Bottle are stainless steel, double walled, and vacuum insulated. The food and drink stay hotter longer. Even after my ski day is done I can still enjoy sipping hot chocolate on the way home. I can’t think of anything much worse than drinking a cold beverage on a bitter, snowy day! One of the most distinct features of the Primus Vacuum Bottle is the click open/close button on the top. Once you screw off the top lid (which doubles as a cup), simply push down on the click button on the second lid to pour your drink. Depending on the thickness of your gloves, it may be difficult to press the button while wearing them. If you don’t want to take off your gloves to click open the top, the easy work around is to just unscrew the second lid and pour from there. A nice feature of the Preppen Jug is its disc of cork on the lid. This no slip surface lets you use the lid as a small backcountry countertop. Place your Vacuum Bottle cup on it as you devour your soup! The Jug’s large lid is easy to grab and unscrew even with your gloves on. Once open, the Preppen Jug’s wide mouth opening makes eating from it simple. Both the Jug and Bottle have a powder coated finish making them easy to grab, hold, and open. If you don’t typically carry an insulated food or drink container on your backcountry ski days you should really consider it. Warm food and hot drinks are a special treat on even a short day out and the Primus insulated food and drink containers are especially good! Wells Lamont HydraHyde Lifty GlovesThe HydraHyde Lifty gloves are by far the best ski gloves I’ve ever worn. This is my fourth winter using this one pair of gloves from Wells Lamont. I have put them through many wet/dry cycles and the leather remains supple, soft, and crack-free. In the past I’ve ruined a few pairs of leather gloves because of my own neglect. Sure, I could have treated those gloves with leather conditioner and kept them in good shape if I had only remembered to do it! With the Wells Lamont Lifty Gloves I don’t have to think about maintaining the leather and that is wonderful from my lazy point of view. Maintenance-free leather gloves save time and money. When I get home from a ski day, I just set the gloves by the wood burner so they can dry. (Wells Lamont does recommend you dry your gloves vertically so if you can hang them or use a vertical glove dryer, that’s even better). The next day the gloves still feel great! From day 1 these gloves have had a comfortable broken-in feel that continues today… even after three years of use. The Wells Lamont HydraHyde is the not-so-secret secret to this great feeling leather. I can’t explain the tanning process but the end result is a water resistant, breathable, maintenance-free leather glove. The water resistance will never wear off. Brilliant! I use these gloves pretty much every cold winter day. For my hands and circulation the amount of insulation is perfect, not too much and not too little. I do wear a lighter pair of gloves on mild winter/spring days, but these are my go-to gloves during our typical cold winter conditions. Here are a few specs:

At around $40 the HydraHyde Lifty Glove is a bargain loaded with value! Julbo Aero Sunglasses (light as air) For a long time I wore sunglasses with lenses that were either too light in bright situations or too dark for low light days. I felt like either Mr. Magoo or a deer with headlights in its eyes, straining for definition. Nothing was ideal until I started using the Julbo Aero Sunglasses. The Reactiv lens is photochromic. They become squint- proof dark in really bright sunny conditions and they lighten up to a clear lens in very low light situations. Based on the conditions, the lens changes to allow between 12% and 87% light transmission. The Julbo Aero lens is a semi-shield shape, meaning that it has just one lens, similar to ski goggles. They offer plenty of “wind in your face” eye protection that prevents your eyes from tearing. The frame design offers plenty of ventilation to prevent fogging. I can’t remember this lens ever fogging up on me. And I do use these sunglasses year ‘round biking, hiking, and skiing. The Aeros are incredibly light and with the photochromic lens it is easy to forget you have them on your face! One Way BC Vario XC Poles This aluminum pole was originally built by Fischer Nordic under the same name - BC Vario. When Fischer bought One Way Sports a couple of years back, they handed off the production of this pole to One Way. One Way has since improved the BC Vario. There are several “best” features with this pole. The first is the “Vario” length. With an easy Quick Lock mechanism the pole length can be adjusted from 95cm to 160cm. This is great news for tall skiers who find that their adjustable poles work well for downhill skiing, but don't get quite long enough for comfortable uphill touring. The One Way BC Vario doesn’t discriminate! I like the cork touring grip, as well. In my early backcountry days we skied with adjustable alpine poles. A traditional alpine grip doesn’t allow for a comfortable backward poling motion in your glide phase like a Nordic grip will. The cork does not transmit cold through your gloves and into your hand as easily as a plastic grip will. The cork offers a nice slip free grip that won’t increase the chances of your hands getting cold! One Way added a length of foam just below the cork grip that adds more gripping options for holding the pole. If you don’t want to adjust the length of your pole (either while traversing a side slope or for a short downhill section) then simply hold the pole on the foam grip without using the strap. Options are always a good thing! The basket size is large enough to prevent the pole from sinking too much in deep snow but it is not so big it feels cumbersome. The basket also pivots or articulates to terrain variations as opposed to a fixed-position basket that might deflect off in some snow conditions. The pole has become a bit lighter under One Way’s production and that is another nice benefit. The last and least important feature is that the pole has a nice powder coat finish. It is a nice, refined look versus a “cheap” painted finish. One Way has definitely put some thought into this pole and made some nice improvements. It is a pole that will enhance your cross country ski or snowshoe day. Some folks may call these four items listed “minor accessories” that don’t need much consideration. They may think warm food and drink on a cold day isn’t necessary. A glove is a glove is a glove. A pair of cheap sunglasses will suffice. Poles don’t make any difference… However, I'd argue that any piece of clothing or equipment that you use and don’t think about while you’re using it is always the perfect piece of gear. A skier who is tired and hungry with hands that are wet and cold, eyes that are squinting or poles that aren't long enough to help keep his balance is likely not having as much fun as he could be. Accessories, or essentials as I like to call them, make all the difference in a snowy world!  Murray Selleck moved to Colorado in 1978. In the early 80s he split his time working winters in a ski shop in Steamboat Springs and his summers guiding on the Arkansas River. His career in the specialty outdoor industry has continued for over 30 years. Needless to say, he has witnessed decades of change in outdoor equipment and clothing. Steamboat Springs continues to be his home. The publication of this original content was made possible by: Erik Stensland's Images of RMNP and Inkwell and Brew.

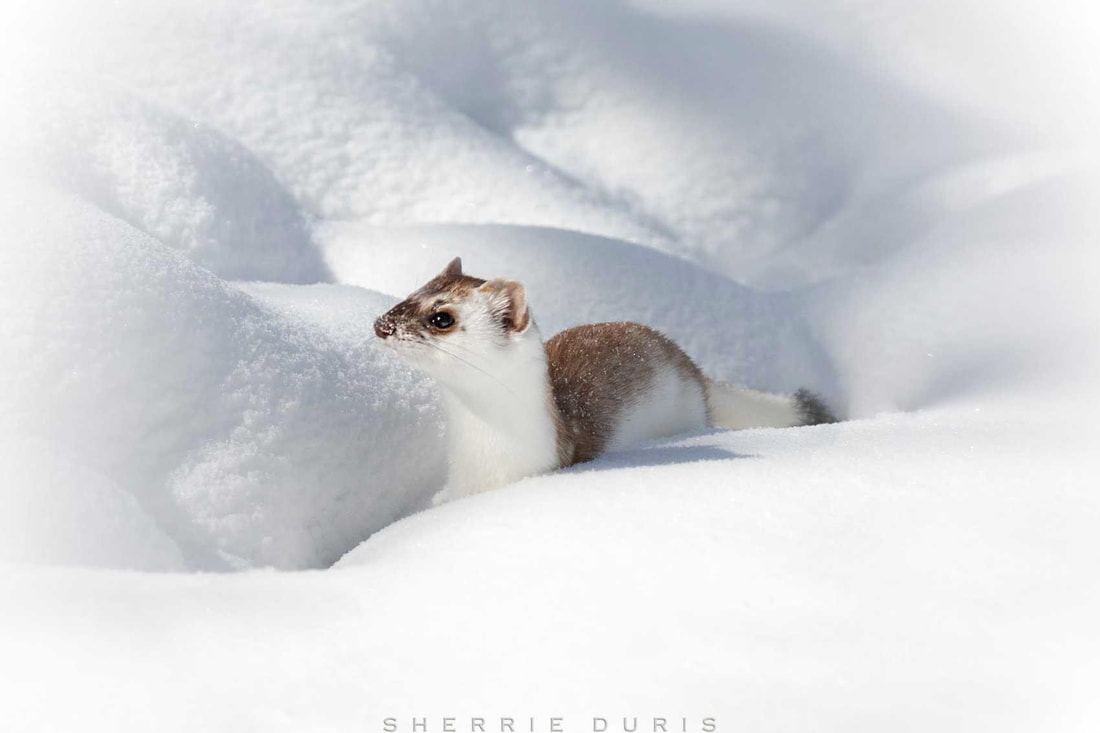

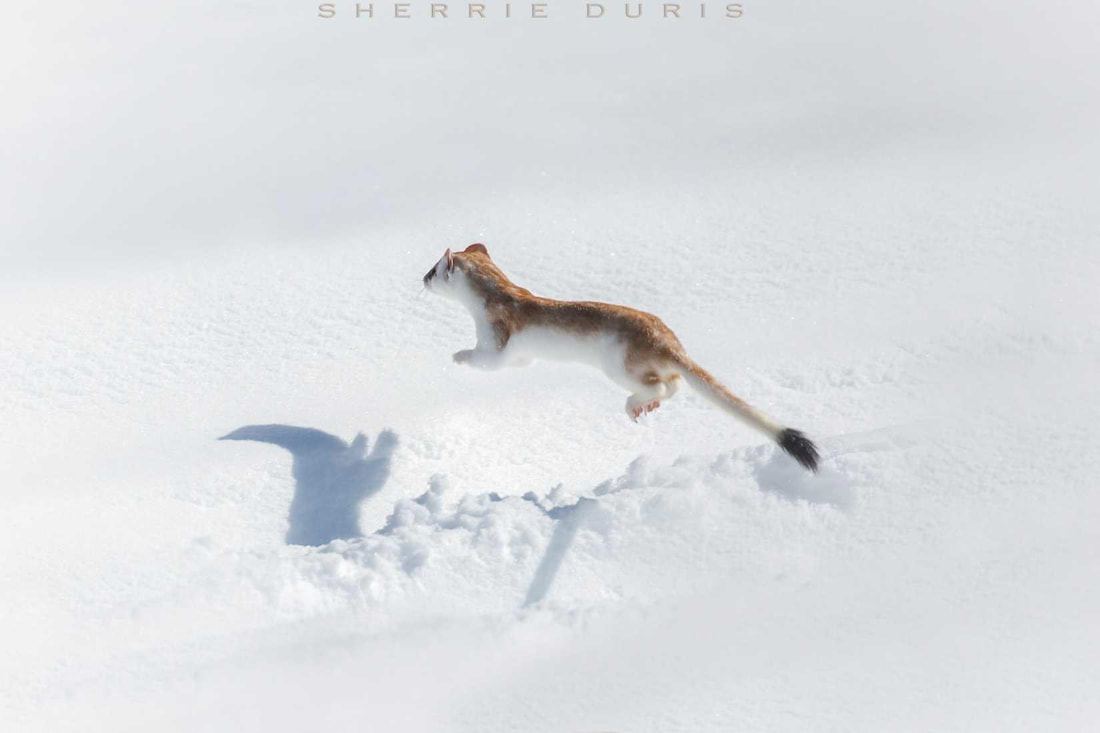

story by Chadd Drott, Walking With Wildlife with Chad photos by Sherrie Durris, Sherrie Duris Photography In the wonderful, wild, and at many times, whimsical world of the weasel, life is only lived in the fast lane. Mustelidae are a family of carnivorous weasels including otters, ferrets, badgers, wolverines, martens, fishers, ermines and mink. Like all members of this family, the long-tailed weasel (Mustela frenata) lives a speedy life. Now, before I get too far into their mysterious lifestyle, I think it would be best for me to tell you exactly what a long-tailed weasel is and what makes them so unique! Although there are many mammals around the world that belong to the Mustelidae family, there are only three recognized weasel species in North America: the long-tailed weasel, the short-tailed weasel, and the least weasel. Colorado has two of the three species with established populations. Both the long-tailed and the short-tailed weasels call this state home, and both are abundant in Rocky Mountain National Park. Out of the three, the long-tailed weasel is the largest and the most abundant in the United States. They are one of many mammalian species that exhibit sexual dimorphism. This means the males are either larger or more colorful than the females (males are larger in this case). Males can measure up to 38 inches from the tip of the nose to the tip of the tail. They can also weigh as much as nine ounces. Females are slightly smaller coming in at 30.5 in. and weighing a maximum of 7.2 oz. If you remember this little rhyme, it will help you to decipher whether the species you are looking at is a predator or prey. “Eyes in front, you're meant to hunt; eyes on the side, you're meant to hide.” This helps you determine that the long-tailed weasel is in fact a predatory species. Throughout Colorado long-tail weasels experience a biannual molt, the changing of their fur color, twice a year. In the summer months, they are brown from nose to about the first 80 percent of their tails along the dorsal line of the body. The underbelly is either white or a slight yellow creme color from the chin to the inguinal region. Their eyes are jet black and face forward on the top of the head. The tip of its tail is also pure black. In winter, their whole body turns a brilliant pure white color, excluding their beady eyes and their black-tipped tail. Why do they molt? When do they molt? And even more curiously, how do they molt? As a tour guide in RMNP, clients are often surprised to learn that long-tailed weasels molt. “Molt? I thought only birds molted?” Although they are not completely wrong as every bird species on the planet does undergo some sort of molt at some point in their life (most birds molt yearly and biannually much like our featured creature), there are many other species around the world that undergo a molt as well. The long-tailed weasel is of them. Molting takes place for two major reasons. The first and most obvious reason is to camouflage from potential prey. Having to capture every meal they eat, predators need every advantage they can get. The second, and the most often over-looked reason, is camouflage from predators. Another great rule to remember when observing wildlife in their natural environment is if you are not the biggest predator, then you are not the only predator. These weasels have to avoid coming face- to-face with coyotes, foxes, bobcats, Canadian lynx, eagles, some owl species, and then, of course, their larger cousins such as badgers, wolverines, and fishers. Molting takes place in mammals because of a chemical/hormonal release in the pituitary gland located at the base of the brain. Similar to our own pituitary gland, both serve many of the same functions which is understandable since we both share the mammalian classification. However, although we shed skin and hair cells, we certainly do not molt in the same fashion as many of our mammalian cousins. The timing of the long-tailed weasel's molt has always been what fascinates me the most. For a species that does not keep time or follow a calendar, they sure do hit the mark right on time year after year. Most people think the molt takes place because it gets cold in the winter and hot in the summer. The actual reasons are due to astronomy and an internal biological clock. Yes, that’s right, the stars literally have to align to allow this little guy to change color. Actually, it’s not really the stars, it’s our planet. Twice a year, in the spring and in autumn, the Earth reaches the right tilt on its axis and is the right distance from the sun resulting in the perfect amount of daylight to prompt molting. During the equinoxes, the weasel's brain starts receiving the exact amount of ultraviolet light from the sun to trigger the autonomic nervous system (ANS). The ANS can be broken down into three more subdivisions; however, for the purpose of this article, we will only stick with the sympathetic nervous system (SNS). The SNS controls how one’s body reacts to every experience and is the main controller of an animal's flight-or-fight reaction. These reactions are dictated by the chemicals and hormones released by the pituitary gland. before the temperatures get too hot or too cold. The pituitary gland is triggered, and the molt begins. After three or four weeks, the molt is complete. Because the amount of daylight is consistent year after year, the molting animal does not run the same risk of hypothermia or hypothermia that it would if it relied on varying annual temperatures. Now that we understand why the long-tailed weasel changes color, I think this is the point where I should bring up that during winter, this species becomes the most misidentified weasel in North America. So, this is the perfect opportunity to explain the differences between the long-tailed weasel and the short-tailed weasel. Long-tail weasels have a couple of classic names, but none that are used today, and there is a good chance you have not heard of any of them. Although the short-tailed weasel is not the most abundant weasel in North America, they are a “Holarctic” species (a species that is found around the circumference of the Earth but only in the northern hemisphere). Short-tailed weasels are also called ermines or stoats. There are a couple ways to identify the two species apart. The first and main way is in the name. The long-tails sport a tail that is about half their body length while the ermine, or short-tails, have a tail that is only a third of their length and not as bushy. Both have the exact same coloring on the tail with a black tip at the back. The only other reliable way for someone starting out trying to ID one or both of these elusive animals is during the summer months, when the long-tails lose the fur covering their feet. Their toes become visible during summer molt while the ermines' feet remain furred the entire year. The long-tailed weasel can be found in any environment in Rocky Mountain National Park. They are found in all three ecosystems: high montane, subalpine, and alpine. They are most often seen in and around waterways throughout the park, taking full advantage of the abundant food sources the riparian areas have to offer. They can also be seen on or along the roadways and trails throughout the park and at any elevation along any rocky outcropping. Nowhere is there a spot safe from the ever curious and always hungry weasel. Their behavior changes dramatically with the seasons and temperatures. Like most animals that live a fast life, they spend the vast majority of their lives either sleeping or hunting to maintain their metabolism. Mating is their only other activity, along with females raising their young, known as “kits.” Males spend any free time fighting off other males for territory. It's a simple but harsh life for the little weasels of Rocky Mountain National Park, but their presence in the Park are a sure sign of a healthy ecosystem for hopefully years to come. Oh and one last thing: Barb, the managing editor of this magazine, asked me to throw in as many cool and interesting facts about these little guys as I could. So, here is one more! The Least Weasel, only found in the northern United States and throughout Canada (not Colorado), has the second-strongest bite force “pound for pound” of any other land animal in the world! Only the Tasmanian Devil has a stronger bite. All weasels kill with a single, crushing bite to either the windpipe and jugular or the more-chosen method, a single bite to the back of the spinal cord. BRUTAL! The least weasel comes in at a whopping 8 ounces, yet it has a full bite force of 85 psi! To put that into perspective, a full grown coyote weighs in at 45 lb. and has a full bite force of 88 psi. To put it in to a little more perspective, humans have a full bite force around 150 psi. If we had the jaw of a least weasel, we would be able to bite a femur bone of an adult cow in half, and it would be like biting ice. The weasel actually evolved around its jaw. It stayed small and took after rodents because it would run out of food if it was apex-predator size and had to maintain an equal metabolism. Last food for thought: if the least weasel would grow to similar dimensions as North America's top predator, the cougar, it would be able to consume every single land animal on planet earth, including being able to bring down elephants and rhinos with a single bite. In fact even the Nile crocodile and the salt water crocodile with the strongest top armor plated necks would be able to be bitten through like butter. So next time you look at someone's pet ferret, just remember what could have been.  Chadd is a 6th generation Coloradan and has been studying and working with wildlife for over 25 years. With an expansive knowledge of the natural world around him, Chadd’s expertise has been solicited for wildlife consultations around the nation. Each summer, he runs the premier wildlife tour in RMNP - voted #1 on Trip Advisor. Learn more about his tours at Chaddswww.com. This piece of original content was made possible by Estes Park Health and Scot's Sporting Goods.

story by Bronte Brooke video footage and photos by Barb Boyer Buck I stumbled across Estes Park this summer and completely fell in love with the area, so it was a surreal feeling getting to experience Rocky Mountain National Park in winter. It had a completely different feel from the hikes I did there back in August. As someone who embraces the cold, I'd been eager to get back there for a winter hike. However, I kept coming up with excuses: not owning a pair of snowshoes, unsure of how to approach hiking in the snow, etc. I'd been pushing it off. Then a friend told me about Hidden Valley: an abandoned ski resort nestled in the heart of Rocky. Of course, as an avid skier, my interest was piqued. My partner and I invited a couple of friends, Hammy and Chucky, to join us and we made a day of it. We work at a ski resort together, so spending all day in the mountains isn't foreign to us; it's become our backyard at this point. But Hidden Valley was a whole new adventure, different than anything we'd done before. The area is a beautiful fusion of hiking and skiing, where backcountry meets established runs. It has the perks and feel of a ski resort without the hassle and millions of people. There are long established runs left untouched, waiting for anyone willing to make the extra trek. You can see sections where lifts used to be and your imagination wanders, filling in the empty spaces, envisioning what it used to look like back in the day. There was a magical feeling, knowing I was standing there experiencing a part of local history. I've been skiing for nearly three seasons now, and finally reaching the point where a typical downhill blue feels a bit like a leisurely drive down the highway. I've been itching for a little more excitement and a few less people, but the idea of fully diving into backcountry skiing intimidated me. The added gear and dangers were also a deterrent. That's why Hidden Valley was such an incredible experience for me! There is that added challenge and satisfaction of having to hike up, rather than simply hopping onto a chairlift. Not having to spend half the day waiting in line? Sign me up! We basically had the place to ourselves, with the exception of a few cross country skiers and snowshoers. Everywhere I looked I was surrounded by beauty, secluded in this hidden oasis. My initial fears of getting lost in tight trees soon dissipated. The area is established enough to feel safe and comfortable, yet removed and remote enough to feel the peace and quiet of the wilderness. The hiking aspect brought me back to that nostalgic feeling of being a kid again; trekking up the tallest hill in the neighborhood just to sled down and then do it all over again. As a crew, we took turns picking out hills that looked fun to shred down and worthwhile to haul our gear up. Some had jumps, some had mellow gradients that wound and wove through scenic terrain. But the best part was that we had no idea what to expect until we reached the top. It was the excitement of the unknown: pick a direction, pick a hill, hike up and send it down! A true “choose your own adventure.” On one of the runs, we hiked quite a way up and took a moment to soak in the views before taking turns riding down. It was so peaceful - a completely different tone than skiing at a resort with all the hustle and bustle. There is a childlike innocence to it all, a feeling of freedom. It felt casual and carefree. We took turns filming each other hitting jumps, hyping one another up. It felt like that first snow day of the season back in middle school: classes cancelled, spending hours sledding ‘til my legs felt like Jell-o and my stomach sloshed full of all the hot chocolate I’d consumed throughout the day. It was a feeling I hadn't felt in quite some time. To top the day off, we had a tailgate cookout in the parking lot before parting ways for the night. As the sun began to set, dainty snowflakes trickled down from the sky, speckling everything in sight with a light powdered sugar dusting. Families drove in to let their kids sled down the bunny slopes before heading home for dinner. We set up our propane stove and sautéed veggies that Hammy had cut up the night before. It was a true campout stir fry of sorts. It brought me back to memories of the summer, backpacking with friends along the Big Thompson River and waking up to make breakfast amongst the birds. If there's one word to summarize my experience at Hidden Valley it's “Nostalgia.” Memories of summer hikes in the Rockies, flashbacks to sledding adventures with friends as a kid, and an overall carefree feeling that reminded me why I have so much love for snowy winters in the Rockies. Don't get me wrong, I absolutely love the summertime in Rocky, but there's something magical about playing around in the snow.

This original content was made possible by: Ram's Horn Village Resort and Tahosa Coffee House

story and photos by Marlene Borneman this story was included in the 2023 Snow Play edition of HIKE ROCKY magazine “You're off to good places, today is your day. Your mountain is waiting so, get on your way.” - Dr. Seuss A spot with deep roots for winter adventures within Rocky Mountain National Park is long-loved Hidden Valley. At 9,240 feet of elevation and thick with Engelmann spruce and Subalpine fir, this narrow valley offered enjoyment in the snow long before it became known as a downhill ski area. As early as the 1930s, locals skied old logging skids and started make-shift runs. According to his book, Recollections of a Rocky Mountain Ranger, Jack Moomaw managed the National Championship Ski Races at Hidden Valley in the winter of 1937. The Colorado Mountain Club also enjoyed many ski and snowshoe outings there in those early years. The Hidden Valley Ski Area officially opened in 1955, providing ski lessons and rentals, as well as a cafeteria, lodge, an ice skating rink and daycare. Hidden Valley certainly filled a niche for locals and the Front Range communities. Local schools took advantage of Hidden Valley and loaded school buses with students for a day of skiing. The last season for the facility was 1991, when operations closed due to financial losses, lack of consistent snow conditions and the I-70 corridor opening access to larger ski resorts. All that remained were materials salvaged to construct the current warming hut and restrooms. Estes Park local Brad Doggett was part of the Hidden Valley Ski Patrol from 1979 to 1987. According to Doggett, there were no groomed trails or modern snow-making equipment when he started work at the ski area. What he appreciated most was the family- focused atmosphere for visitors and staff. Hidden Valley Ski Area provided local jobs and a gathering place to socialize with like-minded people and will always be close to Doggett’s heart. Hidden Valley is still a thriving location for a range of winter activities. Sledding is a popular activity for families and the only place within the park where sledding/tubing is permitted. Children and adults of all ages spend many hours tramping up the hills and swishing down on sleds and tubes. Backcountry skiers, snowboarders and snowshoers are also fond of the recreational opportunities at Hidden Valley. Ski runs from 30-plus years ago provide trails through the heavily forested terrain. The slopes west of the sledding hills are a perfect place to learn and/or practice backcountry/cross-country skiing and snowboarding. The Colorado Mountain School schedules many ski classes and avalanche courses on the higher slopes. Park Rangers conduct SAR (Search & Rescue) Training at Hidden Valley. In 2016, an avalanche beacon training park was installed at Hidden Valley to be used by the public and as a vital part of training for park staff. The purpose of the Beacon Hill is for skiers to practice their transceiver location and probing skills in case of an avalanche. This free service encourages the public to practice avalanche safety. A shovel, beacon and probe are essential avalanche rescue tools and should be carried by all backcountry skiers. (also, see last edition's story, Winter Safety in the Backcountry ) Walkers take advantage of the winter's beauty here. Picnic tables are in place for both summer and winter picnics. Building a snowman is a delight at any age. Many folks visiting from warmer states or countries are thrilled to experience sparkling snow for the first time. On winter weekends Hidden Valley is staffed by VIPs (Volunteers in Parks) fittingly designated “Sled Dawgs.” VIPs help folks locate sledding slopes and ski trails, open the warming hut, provide Park information, and assist in getting medical attention in case of accidents. The goal of a “Sled Dawg” is to provide information on “snow play” fun and safety at Hidden Valley. The Junior Ranger Program is a great addition this winter at Hidden Valley. Park Rangers present a variety of learning opportunities to all ages. Explorer bags equipped with binoculars, magnifying glasses, temperature gauges and informational pamphlets are available to future Junior Rangers. Rangers gladly answer questions about Rocky's wildlife, weather, geology and much more.  Hidden Valley is the perfect place to practice new skiing skills! Hidden Valley is the perfect place to practice new skiing skills! Be aware there are dangers in sledding, skiing, and snowshoeing in a wilderness area. Sledding accidents far outnumber accidents among skiers or snowshoers. According to Mike Lukens, RMNP Wilderness/Climbing Program Supervisor, years ago there were five ambulance runs from the sledding hill in one day! VIPs inform visitors of sledding boundaries, to be mindful of other sledders, and to remind them to walk up the sides of the sledding hill rather than the middle. These simple tips may help visitors avoid accidents. Hypothermia is a real threat. Adequate warm clothing and proper gear is a must. Don't forget sunscreen! The warming hut is a welcome bonus at Hidden Valley offering a heated indoor place to take time for rest; bring drinks and food to keep hydrated and energized. Even in winter months, there are opportunities for bird and wildlife viewing. Stellar’s jays, Clark's nutcrackers, gray jays, ravens, chickadees, woodpeckers, and turkeys are often seen throughout this valley. Moose, elk, and deer enjoy browsing along the willows that poke above the snow. Be watchful for coyotes looking for prey. All sorts of fun can be had at Hidden Valley in the chill of winter. So, layer on your warm clothes, choose your gear, and come play in the snow at Hidden Valley.  Marlene has been photographing Colorado's wildflowers while on her hiking and climbing adventures since 1974. Marlene has climbed Colorado's 54 14ers and the 126 USGS named peaks in Rocky. She is the author of Rocky Mountain Wildflowers, 2nd Ed, The Best Front Range Wildflower Hikes, and Rocky Mountain Alpine Flowers, available for purchase here. The publication of this piece of independent and local journalism was made possible by the Bank of Estes Park and Longhorn Liquor.

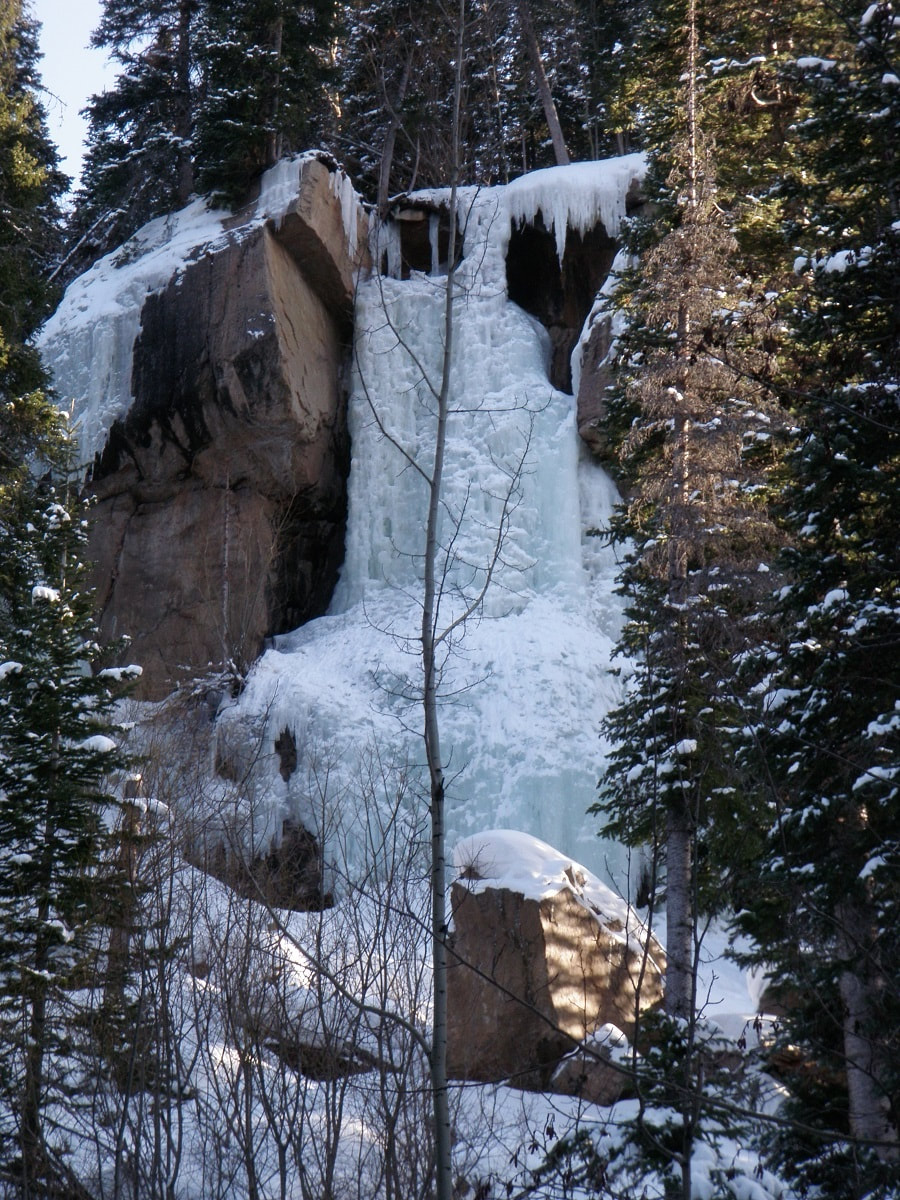

story and photos by Rebecca Detterline The golden peach light hitting the December snow on these shortest days of the year always brings me to a place of quiet contemplation. Pausing at the Saint Vain bridge 2.4 miles from the Wild Basin winter parking area, I breathe in the cold winter air and reflect on the past decade. When I moved to Allenspark in 2012, Wild Basin quickly became my sanctuary. Whether fly fishing in Ouzel Creek, tagging a remote summit or jogging up the Finch Lake trail, I always feel at home in The Basin. During the winter season, the far reaches of Wild Basin are inaccessible to most of us mortals, buried deep under an untouched blanket of snow. Skiing off the summit of Mount Copeland in January of 2017 required starting in the pre-dawn darkness and ‘over-skiing my headlamp’ on a dark, icy trail well after sunset. I almost made it to Thunder Lake on skis in early 2020, but breaking trail in deep snow, route-finding difficulties, and the impending sunset forced my partner and I to turn around just 1/2 mile shy of the lake. The Wild Basin winter parking area will sometimes fill up on busy winter weekends, but spots can usually be found in the nearby summer stock parking loop. Weekdays, however, offer much solitude. Hikers can plan to share the one-mile stretch of road between the parking area and the Wild Basin trailhead with a handful of ice climbers, cross-country skiers, and families trying out rental snowshoes. The road is usually hard packed, as is the short trail that leads to Hidden Falls. However, hikers should carry snowshoes and anticipate breaking trail for destinations along the Wild Basin Trail. In the summer months, Hidden Falls is nothing more than a trickle of water seeping out of an overhanging rock ,100 feet above the forest floor. In the winter, that trickle transforms into a spectacular frozen waterfall, very popular among ice climbers. The round trip distance for this hike is approximately 3.5 miles. From the parking area, follow the road past the Finch Lake trailhead. Just before the road takes a sharp right and crosses the North Saint Vrain Creek, look for a sign for a horse trail and follow the hard-packed trail to Copeland Falls. Continue along the trail, looking to the south for glimpses of this impressive ice column. The climbers’ trail heads up to the left and is generally easy to spot. This trail steepens and continues to the base of the falls, but quickly becomes covered in solid ice. Crampons are needed for this section of trail and hikers should enjoy the views of Hidden Falls from below this icy slope, safely out of the way of any falling ice chunks the climbers might dislodge. Ouzel Falls is a worthy destination in any month of the year, but the most solitude is found on the shortest days. But hikers need not travel 3.7 miles from the winter parking area to enjoy the quietude of Wild Basin in the wintertime. Only .3 miles from the Wild Basin trailhead, winter hikers can revel in the rare opportunity to have Copeland Falls all to themselves. Pausing at the bridge that crosses the North Saint Vrain Creek 2.4 miles into the hike, I watch the water flow between the rock slabs and ice sheets that encase them. So much literal and proverbial water has flowed under this bridge in the years since I’ve made this place my refuge. Through triumphs and heartbreaks, fires and floods, anguish and joy, the trails in Wild Basin have been an enduring comfort. The seasons of life are not so predictable as the seasons of the year, but the ever- flowing snowmelt in the creeks and waterfalls of this magical place always brings a sense of peace. Whether hiking to Hidden Falls, Copeland Falls, Calypso Cascades, Ouzel Falls or destinations beyond, the tranquil solitude of a winter visit to Wild Basin is sure to leave the hiker feeling refreshed and rejuvenated. The darkest days are behind us now and Wild Basin is an ideal spot for quiet reflection as we begin heading for light.  Rebecca Detterline is a lover all things RMNP. She is a wildflower aficionado whose favorite hiking destinations are alpine lakes and waterfalls. Her name can be found in remote summit registers in Wild Basin and beyond. Originally from Minnesota, she has lived in Allenspark since 2011. The publication of this piece was made possible by the Mad Moose, and the Country Market, both of Estes Park.

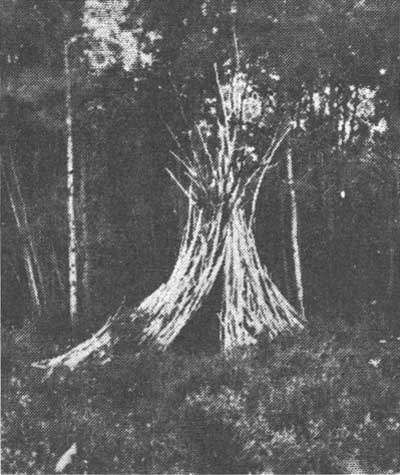

Research & story by Hillary Eichinger  Sprague family homestead in Moraine Park; NPS photo Sprague family homestead in Moraine Park; NPS photo Winter in the Rocky Mountains is harsh, often bringing sub- zero temperatures, frequent storms and high winds. Elk, deer and moose will move down to lower elevations during storms and freezing winds. So why then did early people continue to come back or choose to stay? The easy answer is the abundance of resources and vast sweeping landscapes. Fresh water, abundant wildlife and many wild edible plants attracted people to the dense terrain and high peaks. The Rockies, although severe during winter, provided enough food during the summer and fall to sustain human life. There have been people in the Rocky Mountains and surrounding foothills for more than two thousand years. The Ute Nation believed the creator god Sinawav (Sinauf) specifically placed them in the Rocky Mountains and at Mesa Verde as the chosen people while distributing the other groups of people around the globe. They were to be stewards of the land forming a close relationship to the seasons and changes of the area. The Ute people are not considered nomadic because they returned to the same places, year after year, depending on the season. The area from Denver and Cortez to the east, most of Rocky Mountain National Park and west to Northern Utah, and south to what today is Northern New Mexico were part of their territory. They defended the area fiercely but did not inherently seek battles with other indigenous people that would sometimes include the Arapaho, Cheyenne, Shoshone, and Navajo nations. They traded with Pueblo peoples in New Mexico for pottery to be used in food storage for winter.  “Chief Ouray, pictured here with his wife Chipeta, was one of the most influential leaders of the Northern Ute people in the late nineteenth century. A known intellectual and skilled diplomat, Ouray negotiated treaties and attempted to avoid conflict with whites wherever possible.” (coloradoencyclopedia.org) During the spring and summer months. the Northern Ute bands would break up into family units to return to certain wild crops and hunting grounds. They remembered specific berry bushes, seeded meadows, good places for fishing, and small game hunting areas to return to every year. They also planted seasonal crops like corn, western potato and squashes. The small family groups were careful not to overtax the land, making sure to not take an entire crop or overuse the soil. By leaving some food behind for Mother Nature to recover or for animals to eat, they cultivated the edible resources they would return to. The Northern Utes believed that they were owned by the land, rather than the other way around. They gathered wild mountain foods including chokecherries, wild raspberries, seeds from grasses and trees, pinenuts, and dried crickets. The yucca plant was very important as it was used for basket making, tea, pulp cakes and medicine. The inner bark of the ponderosa pine was harvested for its medicinal properties. It could be used as a compress, to fight infections and as a healing tea. The men would fish and hunt large game such as deer and elk while the women trapped small game like rabbits and ground squirrels and gathered wild berries and seeds. Bison were not hunted in abundance by the Ute Nation until after 1600, when they acquired horses from the Spanish.  Wikiup/NPS photo Wikiup/NPS photo During the late fall when the weather would start to turn cold, they would travel out of the mountains and meet up with other families. The large number of people allowed more protection from hungry predators and attacks from other tribes looking to get quick resources in the winter. The entirety of the band would gather together for the winter months in a few carefully chosen locations. The Northern Ute bands would camp along the White, Green, and Colorado Rivers in what is now known as Utah. This was a time of rejuvenation, food sharing and crafting. Elders would tell stories, pass on traditions, and arranging marriages. Women would make clothing, spending hours on intricate beading patterns that became famous and highly sought after among other tribes. Clothing and moccasins were typically made from animal hides, most often deer and rabbit. Families would stay together for the deep winter until the bear ceremony in the spring, which marked the time when the hibernating bears would wake up and Mother Nature was ready to start a new cycle. The deep winter months in the Rocky Mountains remained empty of humans until the early homesteaders and pioneers built homes on top of the Ute summer sites. The Spanish saw the land of the Utes was full of resources that they valued such as wild game, timber, and fresh water. Because of the harsh weather conditions, rough terrain, and Ute occupation, white settlers did not arrive until 1860 when Joel Estes stumbled on the valley while hunting for a gold deposit. He “claimed” the land by squatting and building two cabins that he and his family used year round. Later he brought up a herd of cattle that had to be watched and guarded constantly from indigenous hunting groups and predators. The ground froze solid in the upper elevations and the cattle had to be brought in close to the cabins to protect them from winter storms and mountain lions. Estes made a small fortune by selling wild game meat in the winter months. He would haul as much meat as he could down the mountain and sell it to the hungry miners prospecting at the base of the mountains in Denver and Golden. Most of the farming work was accomplished in the short summer months and the fall. Hay had to be grown in abundance and stored to last the cattle through the winter. The Estes family relied on stored food, dried meat, and salted fish. The demand was so high for meat that a writing by Milton Estes, Joel's son, reported that he personally shot and killed one hundred elk during a summer and fall season to sell. The trip down to Denver would take four days and then another four back laden with provisions. By the winter of 1864-1865 the weather and living conditions were so severe that the Estes family decided to leave. That winter, Milton Estes described how the snow started in late November and did not thaw until spring. They had to dig through two feet of snow to reach grass to feed the cattle. That year they had to move the cattle down the mountain to save the herd from starvation. Joel sold his claim for a yolk of oxen to a man named Buck in 1866 and in April, the family left, never to return. They settled in southern Colorado and established a ranch where the weather was milder and there was more room for the cattle. News of the Estes family’s valley and beautiful mountain meadows reached other homesteaders and ranchers. Using the trails established by the Ute and other indigenous people, pioneers started ranches, homesteads, farms and timber camps. Once silver and important minerals were found in the Rockies, more mining camps and quarries were established. Lord Dunraven was the first to enthusiastically enter what was now named Estes Park to hunt and attempt to own land for recreation. Winter enthusiasts and mountaineers streamed to the area to enjoy what was described by Lord Dunraven as “long spells of good winter weather interrupted by frequent storms.” Despite the frigid temperatures, intense storms and harsh terrain, pioneers and homesteaders made time for the holidays. Abner Sprague, later to be a land owner himself in what is today Moraine Park, spent two days hiking high into the mountains with a friend to obtain a Christmas tree. The tree was brought back to the community hall in a wagon filled with hay. They put presents that had been obtained in Denver and stashed for months around the tree for Christmas. In Grand Lake in 1883 the Fairview House hosted a New Year’s Eve party. Everyone in the community was invited and a horse-drawn sleigh was sent out to gather anyone who couldn't otherwise make the trek. They enjoyed a large dinner that started at 10 pm and ended with a toast at midnight. Dancing was a popular holiday pastime that people looked forward to it all year. That night they danced until dawn when it was safe to travel again. “The party opened and closed with all joining hands and dancing around the central Christmas tree.” (Grand Lake in the Olden Days, pg 169) Today there are nearly six thousand year-round residents that enjoy winter in Estes Park. Visitors come to Rocky in the winter to snowshoe, hike, and backcountry ski - some of the same activities the pioneers and early native people did. To find out more about native Colorado people and early pioneers, consult these excellent resources: Estes Park a Quick History, Kenneth Jessen, 1996 The Utes, the Mountain People, Jan Pettit, 1990 My pioneer Life, Abner E Sprague, 1999 Early Estes Park Narratives, Milton Estes, 2005 Grand Lake in the Olden Days, Mary Lions Cairns, 1971 https://www.southernute-nsn.gov/history/ute-creation- story/ https://utahindians.org/archives/ute/earlyPeoples.html  Hillary Eichinger was born and raised in Oregon. She received a bachelor's degree in history and a master's degree in museum studies. she has worked with artists in gallery and museum projects for over 20 years. She is passionate about art, history, photography and natural preservation. This piece of independent and local journalism was made possible by Snowy Peaks Winery and MacDonald Bookshop/Inkwell & Brew.

Memoir and photos by Chris Revely Author's NoteMy next few contributions to HIKE ROCKY are based on recollections of four years of employment with the National Park Service (1978 – '81), served mostly around Longs Peak. These memories are vivid. But are they completely true? In the late 1970s, rumors of high winds around Estes Park had reached the East Coast. Meteorologists working on Mount Washington in New Hampshire, where a long-standing world-record wind speed of 234 mph was measured, wondered if that record might be broken along the Continental Divide in Rocky Mountain National Park. As a Longs Peak backcountry ranger, I was recruited to assist with the construction of a wind measuring device on the summit of Longs Peak. Later, the project would require more extensive, personal involvement. In the Fall of 1980 (or was it '81? See authors note) personnel and equipment were assembled at an often-used staging area along the upper Beaver Meadows road. The helicopter arrived and over two days, we made several flights loaded with tools and materials to the summit of Longs Peak . Having proudly struggled to the summit of Longs scores of times under my own power, the experience of rising, effortlessly, in one unbroken line of ascent from the take-off point to the top was both exhilarating and eerily disturbing. My thoughts toggled back and forth between, “WOW!!! What an amazing machine” and “There is just something wrong about getting to the top of Longs like this.” On the flat summit about 100 yards northwest of the often-visited high point, a solid metal mast with its spinning anemometer attached, was secured in a vertical position with several heavy-gauge steel wires tightly anchored to large rocks. Thin transmission wires wound down the post and reached the recording apparatus near the base. We were assured by the Mount Washington team that this arrangement could withstand anything the atmosphere might dish out. As a resident Park Ranger at the Longs Peak trailhead that year, I was unanimously elected (at a meeting I don't recall attending) to service the wind measuring apparatus throughout the winter. It was a project I naively and enthusiastically embraced due in part to the competitive verve that had sprung up around the project. Could Longs Peak beat Mount Washington? Data from the anemometer would be recorded by a stylus on paper if - and only if - the tension spring that turned the paper's cylinder was wound up regularly, like winding an old-fashion grandfather clock. The winding, I was told, should take place once weekly (?!!). The magnitude of the project and my responsibility became disturbingly clear: it would entail frequent trips to the mountain's summit from the Longs Peak trailhead, throughout the winter. Success would depend on regular, reasonable climbing conditions on twenty separate days, from November through March. (Hmmmm….. lots of unspoken ifs in that plan). The winding of the apparatus was achieved with a metal wrench. I would have to remove my heavy, outer mittens and execute the essential maneuver wearing little or nothing on my hands while being slapped around by icy gusts on the exposed plateau. I knew that conditions around the summit would sometimes be so extreme as to preclude reaching the contraption, much less performing the necessary activities out in the open. A plywood coffin-like structure was designed, built and snuggly fitted up against the recorder. Entry to the long narrow box was made through the opposite end, which was fitted with a hinged door. This seemed to solve the problems of access and protection. Once weekly, I left the trailhead with plenty of clothing, food and water. I carried two ice-climbing tools, crampons, a light rope and a few pieces of gear to a place of protection in case conditions on my preferred approach (the North Face) required self-belay. Once past the technical difficulties of the old Cables route, the remainder of the climb involved only kicking steps in snow and finding my way over and around large boulders to the edge of the summit plateau. From there, the last leg of the approach resembled trench warfare. At just the right moment, having waited for a break between volleys of wind, I would break into the open, fully exposed to fire from the enemy, and proceed, crab-like, zigzagging on hands and feet to the coffin, my only point of cover. Once inside, I could relax and take care of business. That winter, between November and late February, I reached the summit (of Longs) on fewer than half of my attempts. My journey to the top always started with the best intentions but often ended in a hail of flying gravel and battering wind below the Chasm View overlook. While the recorder waited patiently for its recharge, I wound it up, more often than not, laying on my side, curled on the floor of a body-size crack below the North Face, laughing at the absurdity of my pitiful situation. At those moments, the decision was easy; if I can't go on safely, it’s time to go down. Turn around at any point on that route and it is all downhill and down-wind to the trailhead. The irony of my situation was, however, harder to escape: There I lay, defeated by extreme wind, the very phenomenon we were most hoping to record. Throughout the winter, I the reached the site when I could and information continued to be collected. Sometime in late February, the steel mast came down and wires were scattered across the summit by (of course) high wind. On New Hampshire's Mount Washington, weather data is collected throughout the year from instruments mounted atop bunker-like, reinforced buildings. Weather station employees travel to the 6,288-foot summit in heated snowcats, spending several days in residence reading instrument gauges while sipping coffee in heated work areas. By comparison, our approach to the hunt for high wind on the 14,256-foot summit of Longs Peak was laughably inadequate; poorly conceived, badly executed and doomed to failure from the beginning. Longs Peak did not officially win the wind speed contest. But I'm not entirely sure it lost. We will never know exactly how much faster the wind blew after the equipment was flattened. Is it worth another try? Today, with improved technology, more sophisticated equipment and a better understanding of wind dynamics around surface features, the odds of success would certainly improve. I suspect there may still be world-record wind waiting to be found among the high peaks of Rocky Mountain National Park. Read a brief synopsis of the wind research project on Rocky Mountain National Park’s website; and, DE Glidden’s report on this project, which was funded by the Rocky Mountain Conservancy is also available online.  Chris Reveley has spent 50 years climbing and doing endurance sports; and, thirty years learning and practicing medicine. “Now I’m a Happy House Husband with hobbies,” he said. The publication of this story was made possible by Images of RMNP and Brownfields.

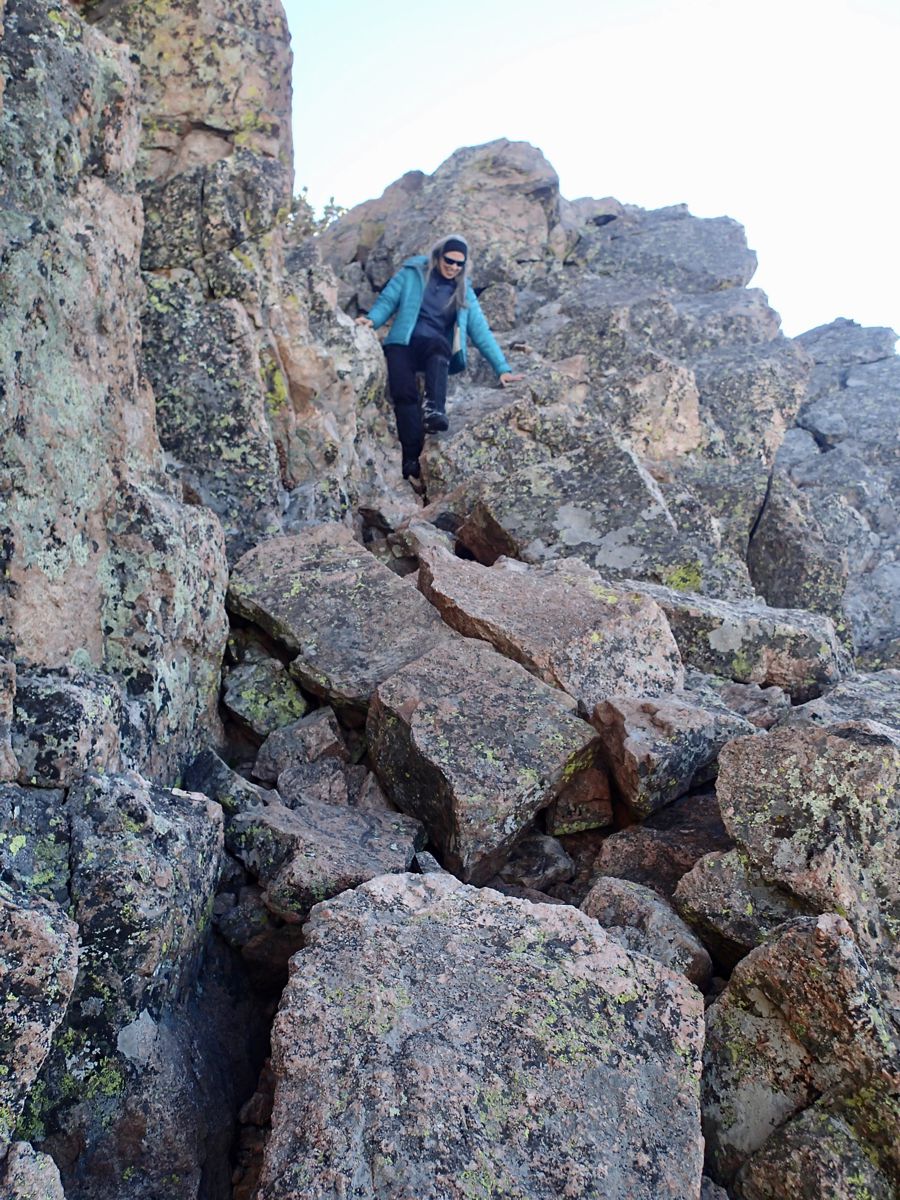

Story and photos by Marlene Borneman While winter officially begins with the Winter Solstice, Rocky Mountain National Park can dish out harsh winter conditions as early as October! Being out in the winter months over the years has taught me to prepare for the unexpected. Frostbite and hypothermia are real risks when traveling in the Colorado backcountry this time of year. Hikers should be sure to check the forecast before heading out. I carry spikes, snowshoes, and layers of clothing to be sure I am ready for the ever- changing conditions. I have come to appreciate Rocky in chilly, snowy and yes, even windy conditions. The landscape is transformed to a peaceful, awe-inspiring, and captivating space to recreate or just to pause. Snow glistens like scattered glitter and icy streams create fine art. The seed pods of common plants are a challenge to identify in their winter form. Lucky hikers may spot a snowshoe hare, ptarmigan or ermine in white winter camouflage. Winter offers so much to observe, learn, and wonder about. Flattop Mountain and Estes Cone have been two of my favorite winter hiking destinations for many years. These trips can range from relatively straightforward to very challenging, depending on weather and trail conditions. Flattop Mountain has given me the extremes. The summit is 12,324 feet in elevation and the starting point at Bear Lake is 9,450 feet. In those 2,894 feet of elevation difference, both the weather and trail conditions can rapidly change in winter. A 2021 winter day started out cold, but not bitter. As I climbed higher the winds became stronger, temperatures dropped to the 20s (not including the wind chill factor) and enough snow covered the trail to require the use of snowshoes.  On a windy, winter day in 2021, the author encountered a covey of white-tailed ptarmigan in their winter plumage. On a windy, winter day in 2021, the author encountered a covey of white-tailed ptarmigan in their winter plumage. Due to the wicked winds up above 12,000 feet, I turned around. But the day was not a loss. On the descent I heard a faint cackling sound which I quickly recognized as a ptarmigan call. Rocky is home to white-tailed ptarmigans which live in the alpine during summer months and go down the to sub-alpine levels in winter, where they can feed on willows at the edges of snowfields. It took me a minute searching the landscape to spot a tiny dark spot in the snow, the eye of a ptarmigan. Soon I saw not one, but about a dozen ptarmigans huddled together sharing their warmth in a snowbank. This sighting made me forget the wind and cold at least momentarily. In contrast, January 5, 2018, was windless and sunny, with mild temperatures and little snow on the trail, requiring only micro-spikes. It was a very pleasant day to be on Flattop. The American Pika was scurrying between the boulders, possibly trying to soak up the “warmth” of this winter day. Pikas do not hibernate as marmots do, but it is still unusual to see them in the dead of winter frolicking around. They often stay near their “haypile” hidden under rocks as most of the plants are buried in snow. On other winter trips on Flattop trail I have caught sightings of dusty grouse and, lower on the trail, turkeys. Estes Cone stands at 11,006 feet, not quite above treeline. Starting at the Longs Peak Trailhead at 9,400 feet, there is often enough snow to wear snowshoes from the start but if not, I carry a pair because up higher, they may come in handy. Soon I reach the junction for Eugenia Mine which is an abandoned gold mine from the early 1900s. Now all that remains are a few timbers from cabins, rusty pots, and tools which are now buried under winter snow. The wide meadow ahead is called Moore Park and is often wind-scoured, resulting in an icy trail. A few winters ago, I spotted a snowshoe hare in winter white along this section. A second junction marks the way to Storm Pass. It is only .7 mile to the summit from Storm Pass; however, the trail becomes gnarly from here. Hikers can anticipate steep, rocky terrain through a tangle of forest. Sometimes I have been able to keep snowshoes on if the snow cover is good, otherwise spikes are the best tool to climb up this arduous section. Below the summit a steep gully, often filled with ice and snow, awaits the hiker, making it a tricky climb to the top. The route flattens out before climbing up to a hefty rock outcropping where the summit rests. Winter months often bring high winds to the top of Estes Cone making the summit stop brief. Despite the wind and cold the summit offers tremendous views in every direction. To the east lay Twin Sisters Peaks, Lily Lake and Lake Estes. Longs Peak Massif rises to the west along with the peaks of the continental divide. The Mummy Range dominates the view to the north. This impressive panoramic view makes every frosty step toward this accomplishment worthwhile. On December 11, 2022, I attempted Estes Cone on a day when high winds caused the snow to form deep layers of crusty snow. Snowshoes were more of a hindrance than a support. The crust would break through in slabs causing the snowshoe to sink. I only made it to Storm Pass that day. In those snow conditions my day was done. I sat a long time at Storm Pass in the still cold, crisp air just taking in this vast wilderness. Not a bad day at all.  Marlene has been photographing Colorado's wildflowers while on her hiking and climbing adventures since 1974. Marlene has climbed Colorado's 54 14ers and the 126 USGS named peaks in Rocky. She is the author of Rocky Mountain Wildflowers 2nd Ed, The Best Front Range Wildflower Hikes, and Rocky Mountain Alpine Flowers. This week's free story is brought to you by Snowy Peaks Winery and Xplorer Maps.

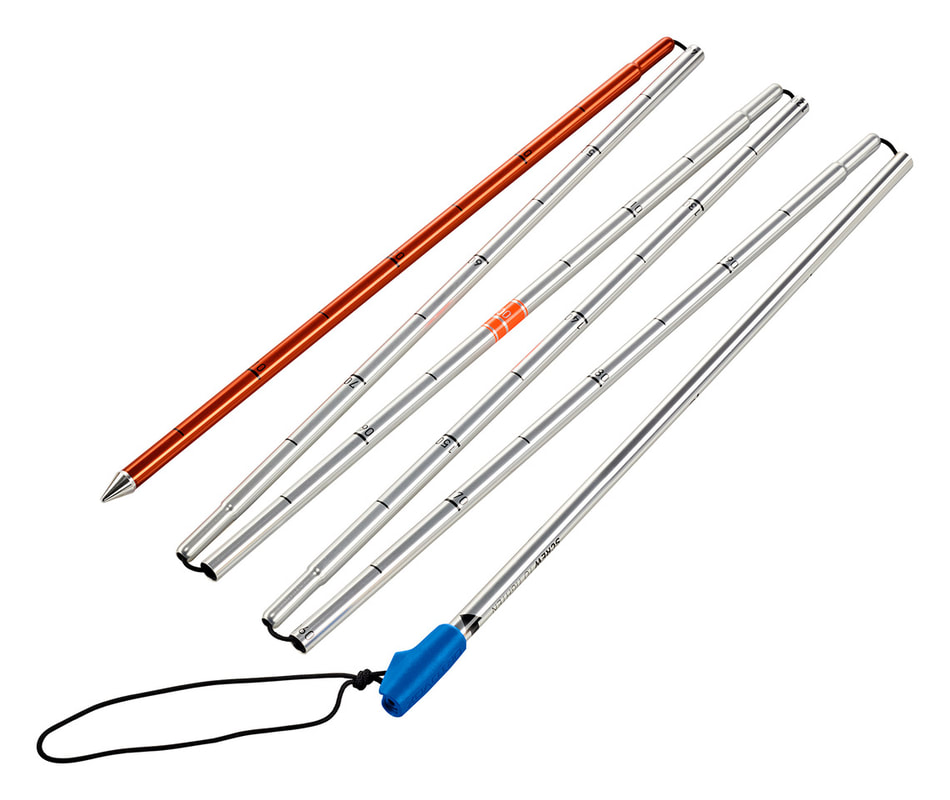

by Murray Selleck, HIKE ROCKY's gear specialist Editor's note: HIKE ROCKY receives no compensation for any of the gear included in Murray's gear recommendations.  Photo by Photo by Hansi Heckmair/used with permission from #Deuter Photo by Photo by Hansi Heckmair/used with permission from #Deuter It’s a beautiful winter day, the sun is out, the sky is blue, the snow is fresh and incredibly bright, you’re with friends, and it seems like the possibilities of the day are limitless. Many skiers will look to make laps harvesting a perfectly magical slope with alpine touring, telemark, or splitboard equipment. Funny, do you see how all the trees on this slope have no uphill branches? Many more backcountry enthusiasts will snowshoe or hike up into tempting snow globes, looking for valleys filled with amazing winter scenery. Holy cow! Look at all those snow cornices above us on that ridge! Or how about a great cross country ski tour through a winter wonderland with perfectly-gladed trees? What was that whumpfing sound? Did you see the snowpack settle a few inches? And look at this crack in the snow! Where did that come from? Oh, the winter backcountry is so compelling. It sings to you to get out and play in it. You might even compare it to Ulysses and the Sirens… there is beauty and attraction but there is an element of risk and danger as well. There’s no need to tie yourself to a mast or stay indoors all winter to play it safe. There are lots of ways to enjoy the winter backcountry on the equipment you love best while staying safe. It all begins with being equipped, prepared, practiced, educated and skilled. Equipped and Prepared Winter backcountry enthusiasts go into the high country ready for anything the day may bring. A backcountry day may begin with nothing but blue skies but it can quickly turn into an unexpected blizzard! If you are planning on skiing, making turns and harvesting a backcountry slope, you should not only carry the three essential avalanche rescue tools (shovel, beacon, and probe) but the 10 Essentials by The Mountaineers. 1 - Navigation (map, gps, compass or something similar) 2 - Headlamp plus extra batteries 3 - Sun protection 4. First Aid Kit 5. Knife or multitool 6. Fire starter, matches, kindling 7. Emergency Shelter 8. Extra food. 9. Extra water or bring a filter or have the means to melt snow for water 10. Extra clothes, additional base layers, extra gloves, hat, and maybe even extra socks! Avalanches aren’t isolated just to those dramatic avalanche shoots beginning above timberline. They can occur on just about any slope, whether it is wide open, or treed, or steep, or moderately pitched. Small slides that run only a few feet can knock you off balance and bury you. Avalanches do not discriminate. They don’t care if you are on skis, snowboards, snowshoes, or snowmobiles. Even if your day includes skiing terrain that you think has no potential to slide you should still consider carrying a shovel, beacon and probe along with the 10 Essentials. No one plans on spending a cold winter’s night out but it can happen to the best of us. How many times have we heard of a person in the backcountry getting hurt or lost and spending a miserable night out unprepared? Will you be geared up and prepared? Unfortunately, we also consistently hear about people not telling anyone where they are going or when they plan on returning home. If no one knows where you are, how can you expect to get help if you need it? Don’t depend on cell phone coverage to help you out of a situation. Think about all the potential “what ifs.” Let someone know where you’re going and when you expect to be back even if you think your outing will only last a couple hours. Remember a guy named Gilligan?  The Ortovox Direct Voice Transceiver is the only transceiver on the market with a voice command feature. A calm and authoritative voice guides you in the right direction to find a buried partner. Other features on the Ortovox Direct Transceiver include a rechargeable lithium battery, 50-meter search distance, easy-to-read display even in bright sunlight, three antennas, product system updates via an app, and an automatic switch from receive to transmit if a secondary avalanche traps a search member who then needs rescuing. Practiced and Skilled Bringing the right gear and wearing the right clothing is always good practice but only if you know how to use your gear and wear the right kind of layers (NO COTTON!). What is the point of carrying an avalanche beacon if you don’t know how to use it? Have you taken an avalanche course? Have you practiced and do you continue to practice with your beacon and ski partners? Do you and your partners test your beacons each time you leave the trailhead parking lot to make sure everyone’s beacons are working properly? How about shoveling? Have you used your shovel to dig a snow pit to identify weak layers in the snowpack? Do you know how to carve out a snow cave or build a snow shelter like a Quinzee hut for shelter or just for fun? Shoveling is hard work.  Ortovox Kodiak Shovel: Digging and shoveling snow is hard work, especially through avalanche debris. In a rescue, snow needs to be moved fast and it is certainly not the time to discover carrying the smallest and lightest shovel is no longer to your benefit. The Ortovox Kodiak is an excellent first-choice shovel. The Kodiak’s blade size will move 3.1 liters of snow fast with each motion. The cutting edge of the blade is sharpened so it won’t deflect off blocks of snow. The Kodiak offers two blade positions. The first is the more traditional shovel shape. The second attaches the blade at a 90 degree angle creating an effective clearing motion… similar to a garden hoe. One person can dig and another person can clear the first person’s snow down and away. The Kodiak’s handle shaft is oval shaped to resist spinning and offers a solid connection between shaft and blade. This shovel is also practical for digging snow pits, snow shelters, or even just to have in the car in case you get stuck. Avalanche debris sets up like concrete. Even digging out a snow cave is sweaty work. And do you have extra layers of clothing including extra gloves to replace your wet layer with dry ones once the shoveling is done? Carry an avalanche probe not only for a rescue situation but use your probe to feel the snowpack on your ski or snowshoe tour. Probe the snowpack along the way and on different slope aspects. You will feel where the soft or crusty or hollow layers of snow that are within the snowpack. This is a quick and easy technique that only adds to your snowpack knowledge.  Ortovox Probes A probe allows for pinpoint location of a buried ski partner. Once you’ve located someone buried in an avalanche with your transceiver, a probe will pinpoint the location and also reveal the depth of the burial. All Ortovox probes assemble quickly with one pulling motion. They come with an oversized tip to improve snowpack penetration and reduce probing friction. They are both light enough and stout enough to probe without deflecting or collapsing. The probes have easy- to-read depth markers which provide valuable information regarding shoveling strategy. Ortovox probes come in several models and lengths from 240cm to 320cm. Do you know how to use your ski equipment? I’ve seen a few folks only steps from the parking lot struggling with their alpine touring bindings, split board bindings, and even XC bindings. The trailhead parking lot is not the place to discover you don’t know what you’re doing! Educated is also being skilled and experienced. A great place to start is the Colorado Avalanche Information Center (CAIC). Here you can sign up for courses to learn how avalanches form, what triggers them, nature’s red flags to look out for, and most importantly, how to avoid avalanches in the first place. The CAIC publishes excellent (and accurate) weather forecasts and posts current avalanche conditions. They offer many additional links through their website to help you gain knowledge and be safe. Avalanche awareness information from Rocky Mountain National Park can be found here. Prepared winter enthusiasts have a practical knowledge of the snowpack’s history including past storm cycles, significant temperature fluctuations between winter storms, and significant wind events. They know the current avalanche forecast and conditions by checking in with the CAIC both the night before they leave and the morning of their trip. And they know how to enjoy a winter’s day and avoid trouble even when avalanche danger is high or extreme. Being educated, skilled, and experienced will help you recognize the warning signs of suspect terrain and the inherent weakness of the Colorado snowpack. If you are brand new to exploring the winter backcountry, find willing knowledgeable partners that can share their expertise with you. Better yet, if you're new to the winter backcountry, you could sign up and take a few avalanche courses or backcountry skills classes to be better prepared to eventually strike out on your own. Avalanche or backcountry skills courses will teach you what causes avalanches, how to avoid them, or in worst case scenarios, what to do in a rescue situation. All of this may sound daunting to the point of asking yourself why even bother going into the winter backcountry? Well, we go for the absolute joy of being outside in the winter. We go for the absolute beauty of a winter backcountry day. And of course, we go for the fun! Mother Nature provides us with plenty of clues that let us know how weak or safe the snowpack is. Experience opens your eyes and ears and keeps you safe. Here are a few of the RED FLAGS Mother Nature provides us all winter long:

This article barely touches on all the things a winter backcountry user should know, bring, and trust. There is much to learn about being avalanche aware and being safe in the backcountry. There is no substitute for education, taking classes, and continually practicing what you learn. No one will ever tell you not to explore the winter backcountry, however, everyone will tell you to be safe!  Murray Selleck moved to Colorado in 1978. In the early 80s he split his time working winters in a ski shop in Steamboat Springs and his summers guiding on the Arkansas River. His career in the specialty outdoor industry has continued for over 30 years. Needless to say, he has witnessed decades of change in outdoor equipment and clothing. Steamboat Springs continues to be his home. This piece of independent journalism was made possible by Brownfield's and the Country Market of Estes Park. To find out how to be a HIKE ROCKY business partner, call 970-449-2620

|

Categories

All

|

© Copyright 2025 Barefoot Publications, All Rights Reserved