|

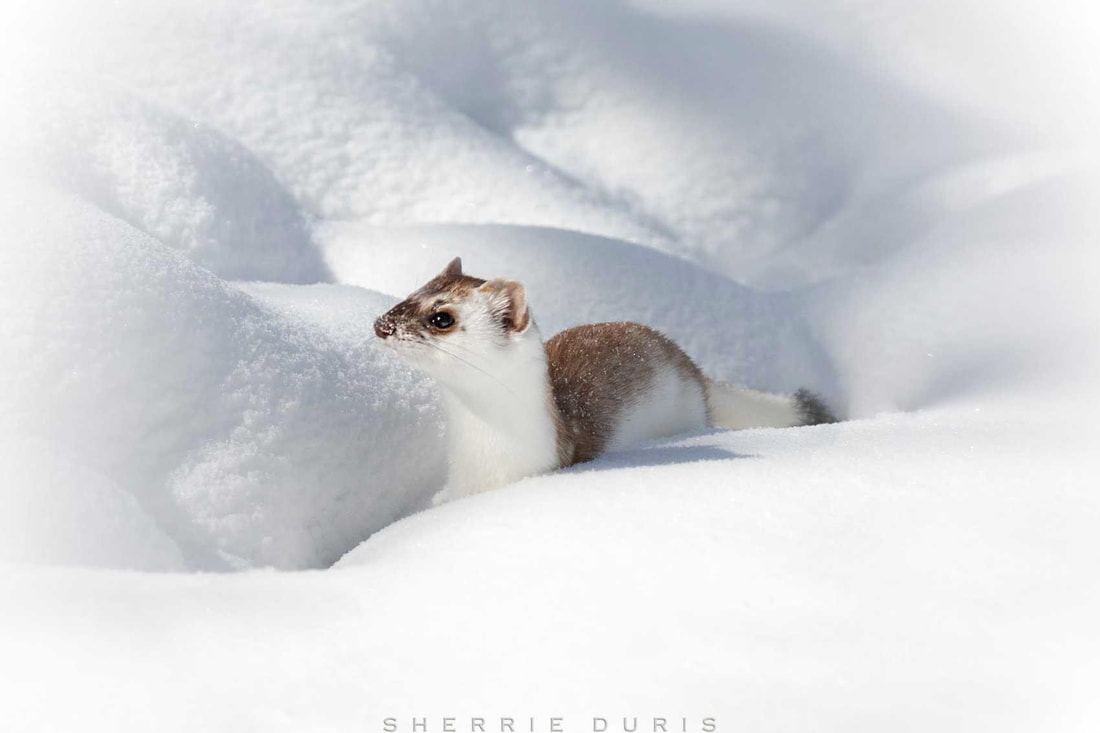

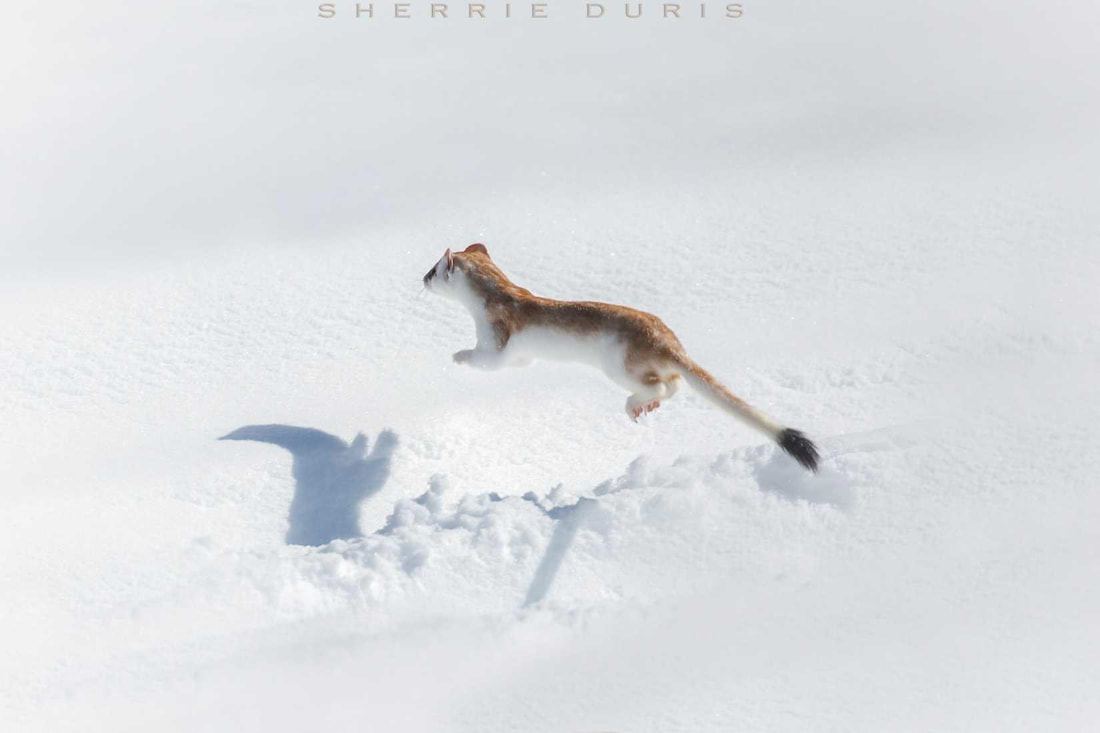

story by Chadd Drott, Walking With Wildlife with Chad photos by Sherrie Durris, Sherrie Duris Photography In the wonderful, wild, and at many times, whimsical world of the weasel, life is only lived in the fast lane. Mustelidae are a family of carnivorous weasels including otters, ferrets, badgers, wolverines, martens, fishers, ermines and mink. Like all members of this family, the long-tailed weasel (Mustela frenata) lives a speedy life. Now, before I get too far into their mysterious lifestyle, I think it would be best for me to tell you exactly what a long-tailed weasel is and what makes them so unique! Although there are many mammals around the world that belong to the Mustelidae family, there are only three recognized weasel species in North America: the long-tailed weasel, the short-tailed weasel, and the least weasel. Colorado has two of the three species with established populations. Both the long-tailed and the short-tailed weasels call this state home, and both are abundant in Rocky Mountain National Park. Out of the three, the long-tailed weasel is the largest and the most abundant in the United States. They are one of many mammalian species that exhibit sexual dimorphism. This means the males are either larger or more colorful than the females (males are larger in this case). Males can measure up to 38 inches from the tip of the nose to the tip of the tail. They can also weigh as much as nine ounces. Females are slightly smaller coming in at 30.5 in. and weighing a maximum of 7.2 oz. If you remember this little rhyme, it will help you to decipher whether the species you are looking at is a predator or prey. “Eyes in front, you're meant to hunt; eyes on the side, you're meant to hide.” This helps you determine that the long-tailed weasel is in fact a predatory species. Throughout Colorado long-tail weasels experience a biannual molt, the changing of their fur color, twice a year. In the summer months, they are brown from nose to about the first 80 percent of their tails along the dorsal line of the body. The underbelly is either white or a slight yellow creme color from the chin to the inguinal region. Their eyes are jet black and face forward on the top of the head. The tip of its tail is also pure black. In winter, their whole body turns a brilliant pure white color, excluding their beady eyes and their black-tipped tail. Why do they molt? When do they molt? And even more curiously, how do they molt? As a tour guide in RMNP, clients are often surprised to learn that long-tailed weasels molt. “Molt? I thought only birds molted?” Although they are not completely wrong as every bird species on the planet does undergo some sort of molt at some point in their life (most birds molt yearly and biannually much like our featured creature), there are many other species around the world that undergo a molt as well. The long-tailed weasel is of them. Molting takes place for two major reasons. The first and most obvious reason is to camouflage from potential prey. Having to capture every meal they eat, predators need every advantage they can get. The second, and the most often over-looked reason, is camouflage from predators. Another great rule to remember when observing wildlife in their natural environment is if you are not the biggest predator, then you are not the only predator. These weasels have to avoid coming face- to-face with coyotes, foxes, bobcats, Canadian lynx, eagles, some owl species, and then, of course, their larger cousins such as badgers, wolverines, and fishers. Molting takes place in mammals because of a chemical/hormonal release in the pituitary gland located at the base of the brain. Similar to our own pituitary gland, both serve many of the same functions which is understandable since we both share the mammalian classification. However, although we shed skin and hair cells, we certainly do not molt in the same fashion as many of our mammalian cousins. The timing of the long-tailed weasel's molt has always been what fascinates me the most. For a species that does not keep time or follow a calendar, they sure do hit the mark right on time year after year. Most people think the molt takes place because it gets cold in the winter and hot in the summer. The actual reasons are due to astronomy and an internal biological clock. Yes, that’s right, the stars literally have to align to allow this little guy to change color. Actually, it’s not really the stars, it’s our planet. Twice a year, in the spring and in autumn, the Earth reaches the right tilt on its axis and is the right distance from the sun resulting in the perfect amount of daylight to prompt molting. During the equinoxes, the weasel's brain starts receiving the exact amount of ultraviolet light from the sun to trigger the autonomic nervous system (ANS). The ANS can be broken down into three more subdivisions; however, for the purpose of this article, we will only stick with the sympathetic nervous system (SNS). The SNS controls how one’s body reacts to every experience and is the main controller of an animal's flight-or-fight reaction. These reactions are dictated by the chemicals and hormones released by the pituitary gland. before the temperatures get too hot or too cold. The pituitary gland is triggered, and the molt begins. After three or four weeks, the molt is complete. Because the amount of daylight is consistent year after year, the molting animal does not run the same risk of hypothermia or hypothermia that it would if it relied on varying annual temperatures. Now that we understand why the long-tailed weasel changes color, I think this is the point where I should bring up that during winter, this species becomes the most misidentified weasel in North America. So, this is the perfect opportunity to explain the differences between the long-tailed weasel and the short-tailed weasel. Long-tail weasels have a couple of classic names, but none that are used today, and there is a good chance you have not heard of any of them. Although the short-tailed weasel is not the most abundant weasel in North America, they are a “Holarctic” species (a species that is found around the circumference of the Earth but only in the northern hemisphere). Short-tailed weasels are also called ermines or stoats. There are a couple ways to identify the two species apart. The first and main way is in the name. The long-tails sport a tail that is about half their body length while the ermine, or short-tails, have a tail that is only a third of their length and not as bushy. Both have the exact same coloring on the tail with a black tip at the back. The only other reliable way for someone starting out trying to ID one or both of these elusive animals is during the summer months, when the long-tails lose the fur covering their feet. Their toes become visible during summer molt while the ermines' feet remain furred the entire year. The long-tailed weasel can be found in any environment in Rocky Mountain National Park. They are found in all three ecosystems: high montane, subalpine, and alpine. They are most often seen in and around waterways throughout the park, taking full advantage of the abundant food sources the riparian areas have to offer. They can also be seen on or along the roadways and trails throughout the park and at any elevation along any rocky outcropping. Nowhere is there a spot safe from the ever curious and always hungry weasel. Their behavior changes dramatically with the seasons and temperatures. Like most animals that live a fast life, they spend the vast majority of their lives either sleeping or hunting to maintain their metabolism. Mating is their only other activity, along with females raising their young, known as “kits.” Males spend any free time fighting off other males for territory. It's a simple but harsh life for the little weasels of Rocky Mountain National Park, but their presence in the Park are a sure sign of a healthy ecosystem for hopefully years to come. Oh and one last thing: Barb, the managing editor of this magazine, asked me to throw in as many cool and interesting facts about these little guys as I could. So, here is one more! The Least Weasel, only found in the northern United States and throughout Canada (not Colorado), has the second-strongest bite force “pound for pound” of any other land animal in the world! Only the Tasmanian Devil has a stronger bite. All weasels kill with a single, crushing bite to either the windpipe and jugular or the more-chosen method, a single bite to the back of the spinal cord. BRUTAL! The least weasel comes in at a whopping 8 ounces, yet it has a full bite force of 85 psi! To put that into perspective, a full grown coyote weighs in at 45 lb. and has a full bite force of 88 psi. To put it in to a little more perspective, humans have a full bite force around 150 psi. If we had the jaw of a least weasel, we would be able to bite a femur bone of an adult cow in half, and it would be like biting ice. The weasel actually evolved around its jaw. It stayed small and took after rodents because it would run out of food if it was apex-predator size and had to maintain an equal metabolism. Last food for thought: if the least weasel would grow to similar dimensions as North America's top predator, the cougar, it would be able to consume every single land animal on planet earth, including being able to bring down elephants and rhinos with a single bite. In fact even the Nile crocodile and the salt water crocodile with the strongest top armor plated necks would be able to be bitten through like butter. So next time you look at someone's pet ferret, just remember what could have been.  Chadd is a 6th generation Coloradan and has been studying and working with wildlife for over 25 years. With an expansive knowledge of the natural world around him, Chadd’s expertise has been solicited for wildlife consultations around the nation. Each summer, he runs the premier wildlife tour in RMNP - voted #1 on Trip Advisor. Learn more about his tours at Chaddswww.com. This piece of original content was made possible by Estes Park Health and Scot's Sporting Goods.

1 Comment

Marge Johnson

8/25/2024 04:25:03 pm

We live in Tabernash, Colorado and we just had a juvenile weasel on our patio - no photo but 3 witnesses. Our area has had the fox population decimated by mange this summer, so I assume this has made room for the weasels, since there is lots to eat now. So your article was very helpful in identification and understanding their role in our ecos

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

|

© Copyright 2025 Barefoot Publications, All Rights Reserved