|

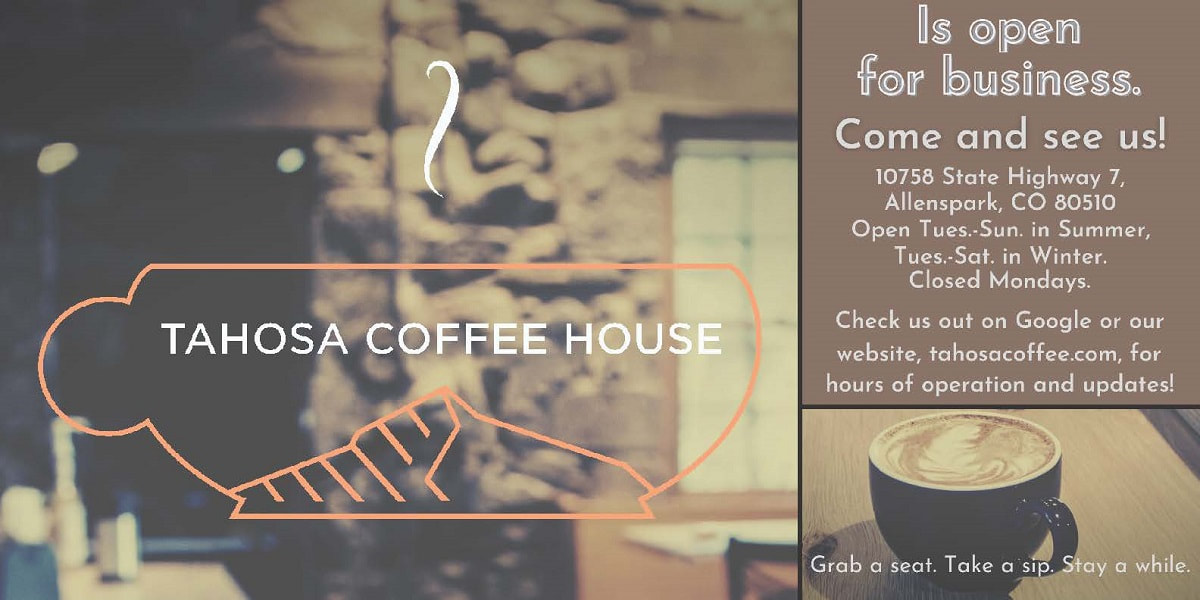

story by Chadd Drott, Chadd's Walking With Wildlife The best time to visit Rocky Mountain National Park depends on the purpose of your visit. From backcountry skiing on fresh powder to a beautiful summer day on the summit of Longs Peak, Rocky has something for everyone. However, if you are visiting for the sole purpose of spotting wildlife, there are two times in the year that are best. I recommend coming out during the middle two weeks of September for the fall colors and the peak of the elk rut. However, my recommendation for viewing the most amount of wildlife, and to witness the miracle of life, would be the first two weeks of June. It's baby season in the Park! Visitors may think of calving season as an unlikely time to spot wildlife, assuming that mothers will be hiding their babies in attempt to keep them safe from predators. However, the situation is quite to the contrary. Mothers must come out to eat in order to produce the milk to feed their young and many newborns start following their mothers to feed just a few weeks after being born. This is the best time of year to see many species with their babies. Many animals will have given birth in Rocky in the weeks prior to your visit and others will be calving during your visit. This time of year offers the best time to see many species with their babies when they are the youngest. These are the animals you will most likely see with their young in early summer in the national park. Rocky is best known for Rocky Mountain elk. Elk drop their young starting in late May, continuing through the first half of June. Most young are born in the cover of thick, dark timber outcroppings or on steep hillsides that are close to timberline. Newborns are able to stand up within twenty minutes of being born, and can walk and run within two weeks. Babies lay by themselves in tall grass under the cover of trees. They will lay still on the ground, motionless and with no scent. These two adaptations are their only line of defense from being discovered by a predator. When nursing, the mother will stay a few yards away and the calf will come to her. After nursing, the calf will move off a distance and drop back down. The mother will spend as much time away from her calf as possible the first week to two weeks. Calves are born around 35 pounds and will weigh roughly 63 pounds by the end of the two weeks, at which time the mother brings the calf from the cover of trees and reunites with her herd and their new calves. Elk will spend the next two months nursing their young until they are fully weaned. Even though youngsters will be weaned by month two, they will retain their spots for another four months. Calves will stay with their mothers for the first year and then dissolve into the rest of the herd as the mother moves into the forest to have another round of young.  Mule deer twins and their mother in Rocky/ photo by Dave Rusk Mule deer twins and their mother in Rocky/ photo by Dave Rusk Similar to elk, Mule deer also have babies in May and June. The fawns are born with spots and are also scentless. They use some of the same tactics as elk do, birthing in dense forests with optimal cover. Because deer fawns are so small, mule deer use another tried and true tactic to help ensure their fawns' survival: they choose extremely steep inclines high up in the dark timber where it is hard to traverse. This helps keep wandering predators away from the fawns and lowers of the chance of them stumbling upon one. Deer fawns and elk calves are born with spotted fur. The spots break up their body's outline while it is lying on the ground. In dense forests, the sun peeks through the branches and dapples the forest ground. As the sun passes across the little one's body, it creates a light image on the fur, giving the illusion of grass dancing in the wind. It's the perfect camouflage from the peering eye of a curious predator. If the predator can't smell it, see it or hear it, then it becomes almost impossible to find. Unlike moose, deer and elk cannot close their nostrils to hold their breath, so hiding in water from predators is not an option. Rocky's Shiras moose could be seen as the sole member to a unique family of semi-aquatic mammals, but actually they are just the largest members of the Cervidae (deer) family. Moose deliver around the same time period as elk, but a little earlier: most of their young are definitely dropped in the month of May. Unlike mule deer fawns and elk calves, baby moose are not born with spots. Instead, newborns have a milk chocolate brown coat and are not born scentless. However, moose calves have their own unique adaptations for survival. Moose are able to stand up and have steady legs within the first couple of hours of birth. And within three days of birth, they become faster than even Usain Bolt (known as the fastest human on earth). That's right, moose calves run faster than humans by day three, topping out at speeds in excess of 30 miles per hour. Their front legs are taller than their back ones, which gives moose calves the torque to accelerate extremely fast. If all else fails, they are able to swim more than 10 miles per hour by day two and will retreat with mom into the water if they are unable to outrun a predator. While sightings of deer, elk and moose offspring are relatively common, count yourself quite lucky if you see any of the following animals with their babies in Rocky Mountain National Park. The measures taken by Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep to protect their young from predators are nothing short of harrowing. Although not quite as amazing as the mountain goats' defense tactic of having young on the side of a sheer vertical cliff, bighorn sheep still choose steep and rocky terrain to help guard their young from predators. In fact, although many species would prey upon a baby lamb if given the chance, bighorns in Rocky have narrowed that down to two predators because ewes take their lambs into steep canyons and high up on rocky cliffs near alpine meadows to raise them. The two major predators of bighorn sheep might surprise you. Mountain lions are perfectly adapted to run lambs down over rocky terrain and take full advantage of any of those opportunities during birthing season. The other main predator of lambs is the apex air-superiority predator, the Golden eagle. Lambs are actively hunted by eagles during the first couple weeks of life through their first year. After that, they tend to weigh enough that eagles choose to go after the next year's young. Coyote pups are born after a short, 63-day gestation period, earlier then the deer family’s fawns and calves. Coyotes tend to be born in the beginning of April and start to venture out of the den by the end of May, making early June the perfect time to see puppies outside of a den site. The hardest part about seeing these little ones is that coyotes are very good at keeping their den sites well-hidden from the prying eyes of predators. Some years, coyotes have been seen denning in the middle of one or more of Rocky's large parks. This presents the best opportunity at seeing baby coyotes in Rocky. Unfortunately, life is hard for both predator and prey in the wild, and when a den site is discovered by a number of species the pups may be killed for either food or to eliminate the threat of them growing up and becoming one of the Park's top predators. Bears, foxes, wolverines and eagles will kill pups as a food source. Elk, deer and moose will trample pups to help ensure future generations of their own young will survive. This was unfortunately the case with one famous coyote den last year that was discovered by a few cow elk; eight of the nine pups were killed by trampling and the remaining pup was moved to a new location by the parents. The least likely of our most recognized species in Rocky to be seen with their young is the American black bear. But black bears are not the rarest of large animals in the park to be seen with cubs, that would be the mountain lion. Bear sows unsuspectingly give birth to their young inside of their dens in late January or very early February. It is not until the sow wakes from her torpid sleep in March or April that she discovers her offspring. She will not emerge with her cubs until mid-April. Due to the extremely low population within Park boundaries and the fact sows like to keep their cubs hidden, seeing a bear with cubs in RMNP is a rarity for sure. However, like many things in our beautiful Park, it is never impossible to see them. Look for bears with cubs in lower lying areas around 9000' such as Ponderosa pine forests or large groves of Aspen. These trees give the cubs the best opportunity to climb up if needed when trouble arrives. This elevation also provides the best opportunity for food sources within the park. Both flora and fauna are plentiful in the high montane region. Unlike many other species who have young year after year, black bears are a biannual species. They give birth only once every other year and raise their cubs for almost two years before chasing them off during the cub's second June. Cubs will end up spending seventeen months with their mother, learning everything that they need to for surviving on their own. Mothers chase off their cubs in early spring once the weather is best, to help give the cubs the most time available to figure out life on their own before the harsh winter hits. Although it seems cruel, believe it or not, this is their mother's last loving gift to the cubs. She has waited until the days and nights stay warm and food is plentiful to find and forage upon. Most cubs are experts at survival by this time anyway. As long as they can avoid other larger bears and people, they should do just fine living a bear's life until it is their turn to reproduce, and add to the survival of their species. A few months later the mother will mate again in fall and be ready to start all over again come January! Editor's Note: As a reminder, wild animals with young are extremely dangerous to humans. Rocky Mountain National Park's wildlife viewing guidelines should be adhered to in all situations if possible. VIPs (Volunteers in Parks) often patrol wildlife sightings in the Park to help keep visitors at a safe distance, but ultimately it is your responsibility to know the dangers and mitigate for them.  Chadd is a 6th generation Coloradan and has been studying and working with wildlife for over 25 years. With an expansive knowledge of the natural world around him, Chadd’s expertise has been solicited for wildlife consultations around the nation. Each summer, he runs the premier wildlife tour in RMNP - voted #1 on Trip Advisor. Learn more about his tours at Chaddswww.com This piece of original content, included in the current issue of HIKE ROCKY magazine, was made possible by Longhorn Liquor, Scot's Sporting Goods and Tahosa Coffee House.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

|

© Copyright 2025 Barefoot Publications, All Rights Reserved