|

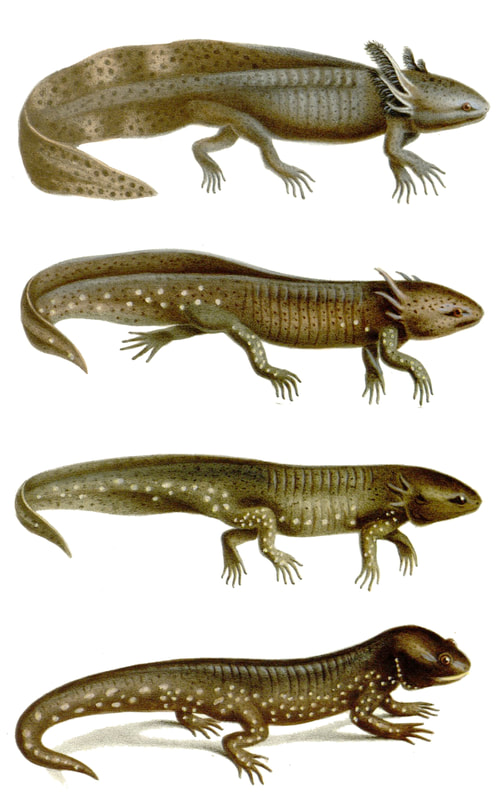

This article is extracted from the current issue of HIKE ROCKY magazine; to learn more about becoming a member to read the entire publication, click here Climate change may be forcing more Western Tiger Salamanders to become terrestrial Photo, video, and story by Barb Boyer Buck, Managing Editor On a beautiful morning in late September, the surface of Lily Lake was still as glass. I walked out onto the fishing platform that extends above the lake and gazed into the water. “What is that?” exclaimed my friend Krissy, pointing to an odd creature just emerging from under a rock to walk along the muddy lakebed. I was stumped. I have studied, lived near, and visited Rocky Mountain National Park for nearly 25 years, and I had never seen such a creature. It was definitely an amphibian and had frilly gills extending from both sides of its head. Suddenly, another one emerged and began walking in another direction to burrow its head into the mud among the grasses. Neither came up for air the entire time we watched them. My group of friends turned to me, quizzical. I was supposed to be the expert, after all; the people I was with were only in town to work for the summer/fall and were brand-new to the area. I spied a group of rangers and some of the Park's trail crew working nearby and asked them to come over. The video accompanying this story shows this rarely-seen denizen of the deep in action. A few rangers were nearby and identified them as Western Tiger Salamanders; they looked exactly like dark-colored axolotls. I had to know more. I spoke with Jonathan Lewis, Wildlife Response Technician and Bear Management, Amphibian, and Avian Programs Lead for RMNP. He explained that sometimes, the tiger salamander stays in this newt-like stage, “with external gills that look like a dragon” for its entire life.  NPS/ROMO photo NPS/ROMO photo “The gills filter the oxygen from the water,” Lewis said, “That way, they don't ever need to come up for air.” The ones who “choose to leave the wetlands” will mature further into the full-grown creature, more easily recognizable as a salamander. But these “mud puppies” can grow up to a foot long and never leave the water. “This is one of the largest salamanders, less than 14 inches long, and one of only four amphibians native to RMNP,” Lewis explained. Although common – “a saturated species,” according to Lewis – they are very rarely seen because they are mostly nocturnal and live most of their lives underground. They hibernate underground, too. “They are ravenous predators, sometimes eating aquatic insects found in the mud, and can even be cannibals” he added. They live a long time, too – “more than 10 years, about 13-14 years in the wild. “Mating season is in the spring, when they congregate to the same pond where they were born,” said Lewis. “Females will lay clusters of up to 10-15 eggs, or even single eggs. When they are born, they look like little tadpoles with legs and gills. They swim in the warmer water; in the shallows. For those who choose to fully mature, that takes about three months. Its tail is very poisonous and even the membrane on its skin is slightly poisonous – do not touch these creatures if you happen to come across one! It’s scientific name is Ambystoma mavortium, a type of a mole salamander, and ranges from southwestern Canada all the way to northern Mexico. Unfortunately, as many other species in RMNP, the Western Tiger Salamander is being affected by climate change. In a study completed in 2005 in Lamar Cave in Yellowstone National Park, Temporal response of the tiger salamander (Ambystoma tigrinum) to 3,000 years of climatic variation , researchers concluded that further warming and drying climate conditions would significantly reduce these “mud puppies” in RMNP. “The Yellowstone study suggests that Rocky Mountain National Park staff and visitors may start seeing fewer paedomorphic and more, larger terrestrial adult tiger salamanders as conditions continue to warm two to five degrees centigrade as predicted in the region of the park based on the two most widely accepted climate models. What this would mean to tiger salamander population numbers, which are currently thought to be stable, or to populations of other park amphibians known to be less well off is still unclear.” (source: https://www.nps.gov/romo/learn/nature/tiger_salamande rs_climate_change.htm ) It was such a thrill to discover an animal I had never seen before, even after studying Rocky for nearly 25 years! There are so many surprises waiting for everyone during explorations of this wonderful national treasure if you take your time, stay quiet and still, and most importantly: leave no trace.  Barb Boyer Buck is the managing editor of HIKE ROCKY magazine. She is a professional journalist, photographer, editor and playwright. In 2014 and 2015, she wrote and directed two original plays about Estes Park and Rocky Mountain National Park, to honor the Park’s 100th anniversary. Barb lives in Estes Park with her cat, Percy. The publication of this piece of local and independent journalism was made possible by The Country of Estes Park and MacGregor Mountain Lodge.

2 Comments

Cassie

7/14/2024 10:58:05 am

So helpful! We saw this last night at Rocky Mountain NP and was very curious!

Reply

Dave

7/15/2024 08:38:40 am

That's so awesome! Thank you

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

|

© Copyright 2025 Barefoot Publications, All Rights Reserved