|

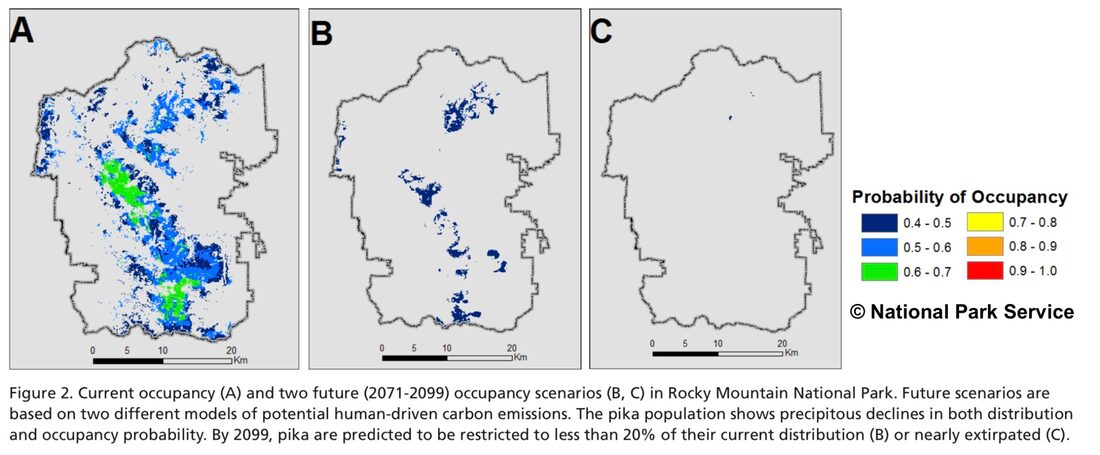

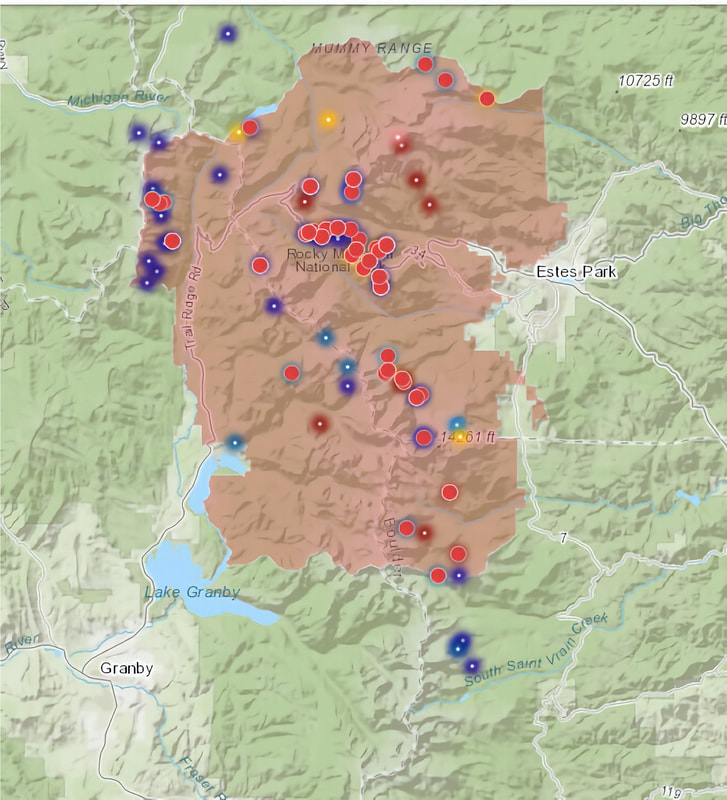

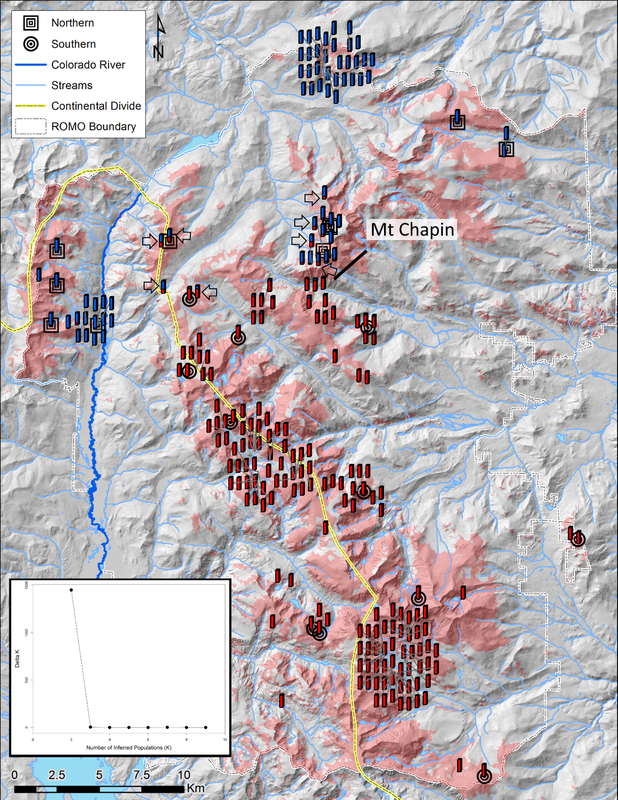

How climate change is impacting pika populations in Rocky by Barb Boyer Buck The tiny American Pika, one of the most daring and weather-hearty animals in Rocky Mountain National Park, is exhibiting declining population numbers all over Colorado due to climate change. Dr. Chris Ray, a research associate at the University of Colorado, has been studying the American Pika for several decades. In February of 2022, she and a researcher from Northern Michigan University, Hilary Rinsland, presented the most recent findings of their work and the Colorado Pika Project in the Science Behind the Scenery seminar series. The series was sponsored by Rocky and the Rocky Mountain Conservancy and ran from mid-February to mid-March of this year. “We started surveys of the American Pika in Rocky Mountain National Park ten years ago,” Dr. Ray said during her presentation in the series. “We focused on pikas because they have several traits that make them a sentinel (species) for the effects of climate on wildlife. “It’s relatively easy to determine if they are occupying any given spot. Also, they inhabit rocky areas that humans tend to avoid; so, compared to many other species they should be less affected by human activities, other than human-caused climate change.” Pikas are particularly climate-sensitive, needing access to cool climates in the summer and protection from sub-freezing temperatures during the winter time, she explained. The American Pika, Ochotona princeps, is native to Rocky Mountain National Park, and other high- elevation locations in the state. They occupy talus, or scree-slope, habitats above treeline. Busily gathering greens all summer, pikas are the tiny animals in the rabbit family who are often heard chirping communications to their compatriots. Pikas create hay piles upon which they feed all winter, while nestled underground under rocks and a thick layer of snow. They are an incredibly charismatic species, with big ears (similar to a famous cartoon mouse), and they need our help. “By mid-century, population would dip below 50% of occupancy and that population would start to contract dramatically under business as usual,’ (or, no changes in greenhouse emissions),” Dr. Ray said. “The changes in population are based on predictions of the above-surface climate, but pikas spend a lot of time under the surface. So, we are monitoring all their micro-habitats, too, hopefully to support our understanding of flora and fauna changes in relation to pikas,” said Dr. Ray. “We couldn't do all this monitoring without the help of the community,” she said, citing the “impressive community science project, the Colorado Pika Project.” This project was created by the Denver Zoo and Rocky Mountain Wild, which manage the volunteer efforts of monitoring the American Pika not only in Rocky, but also along the Front Range and in the White River National Forest. “In 2021, 56 volunteers surveyed 72 randomly-selected plots,” said Dr. Ray. “Twenty-four plots are surveyed every year and additional plots are surveyed in even or odd years so that more of the Park can be surveyed with the limited pool of volunteers. “The plots are small but that’s important because it takes a while to survey the 3D plot for pika science.” Volunteers look for pikas, listen for pika calls, and look for pika sign, such as fresh/old hay piles and fresh/old scat. Other observations taken include signs of other species such as ptarmigan, marmots, and weasels. The compilation of results is mapped above (a more detailed, ARC/GIS interactive map can be found here.) The red dots are sites where no pika sign was found, the yellow are where old sign was found and the cooler colors indicate where pikas or current pika sign was found. “Occupancy is declining in different kinds of models with a rise in temperature across the landscape,” said Dr. Ray. Areas of higher concentration of pikas were found where the crevice-depth was deeper, indicating “where pikas have more ability to get away from the climate,” she said. Recently, two sub-species of the American Pika were found in Rocky, explained Hilary Rinsland. She was lucky enough to conduct further research in the Park when it was closed to visitors, during COVID. She collected blood and scat samples to screen for disease and parasites, which may also be impacting pika populations. The two genetic clusters and assignment to either the north (blue) or south (red) clusters are indicated on the map below. Darker circles indicate multiple samples from that locality. “The modeling suggests that the southern sub-species was going to be particularly vulnerable to habitat loss,” said Hilary. “Pikas are poor dispersers and cold sensitive, it may become impossible to re-colonize.” “Knowing that, and thinking about the subspecies, we wanted to do a study” that incorporates all these factors, Hilary continued. “Pikas are moving to higher elevations as temperatures are getting warmer.” She explained that the protocols used in her studies were the same one as the Colorado Pika Project were using, to ensure a seamless interface when comparing the results of monitoring. You, too, can help with the American Pika studies in Rocky by signing up as a monitoring volunteer with the Colorado Pika Project. You can find detailed information on the opportunities available in Rocky here: https://pikapartners.org/rmnp-resources/ We also need to do our part to combat climate change in our own habitats, if for nothing else than the plight of the American Pika. This wonderful creature deserves to keep its home forever, in Rocky Mountain National Park.  Barb Boyer Buck is the managing editor of HIKE ROCKY magazine. She is a professional journalist, photographer, editor and playwright. In 2014 and 2015, she wrote and directed two original plays about Estes Park and Rocky Mountain National Park, to honor the Park’s 100th anniversary. Barb lives in Estes Park with her cat, Percy.

0 Comments

“Like wildflowers, You must allow yourself to grow In all the places People thought you never would.” - Winston Porter Story and photos by Marlene Borneman I spend hours in Rocky each spring/summer with my loupe and camera in hand identifying and photographing native wildflowers. I'm hopeful one day to spot a new or rare species. Rocky embodies several life zones: foothills, montane, subalpine, and alpine. Each life zone hosts a diversity of habitats providing a variety of plant life—from dry forested hillsides, open meadows, lush wetlands, rocky scree slopes, to sweeping tundra. Some wildflowers even prefer to plant their feet in disturbed areas caused by fire, floods, avalanches, animals, and humans. Wildflower hikes are a terrific way to explore the Park. With increasing interest in identifying and photographing native plants comes a need to protect these plants and their habitats. Leave No Trace Center for Outdoor Ethics and their Seven Principals have been around since 1990 (see November 2021 Issue of HIKE ROCKY). Did you know there are Wildflower Ethics too? I'm partial to the company of wildflowers. I look forward to meeting the first spring wildflowers sprouting up in March and April. This delightful time, however, often results in damage to plants, habitats, and trails. Spring is the time when nature's emergent gifts are most vulnerable. Locals refer to spring in the mountains as “mud season.” With melting snows and run offs the trails become muddy and filled with wide, deep puddles. The trails may be still icy and snowy. It is so tempting to hike around puddles/mud/ice/snow. But hiking around these obstacles causes “social trails” damaging vegetation that may take decades to heal. The well-known cliché, “Leave Only Footprints and Take Only Memories,” is a good start. However, a hiker’s footprint placed in the wrong spot can cause irrefutable damage. Trampled grasses start to resemble a trail and others will follow. The most beneficial act a hiker can do is walk right through nature's obstacles. It makes me happy to see boot prints on muddy trails! Mindfulness and wildflower hikes go hand in hand. Mindfulness is characterized by a slow pace, thoughtfulness, being gentle, nurturing, searching and curious, and being in the moment. Wildflower hikes certainly take on these characteristics. When in nature staying in the moment builds skills in identifying plants while ensuring their integrity. I get absorbed in giving my full attention to the minute details of flowers. I hike slower. I'm patient with locating plants and diligent in seeking out a heap of research. Every mindful step saves a plant, a trail and maybe an insect or two. I'm also mindful of the hard work trail crews perform in building trails for my recreational use. Shortcutting around muddy or icy trails makes their work twice as hard in repairs. Stay on established trails. The alpine tundra is especially open to destruction by hikers. The alpine tundra is a fragile ecosystem hosting several plant communities. Wildflowering on the tundra demands mindful thinking. Even moving a small rock can be a death sentence for a tiny alpine flower. Again, stay on established trails when possible. The alpine flowers are true survivalists adapting to several challenges. They endure a short growing season, strong winds and storms, freezing temperatures and often drought conditions. Despite these challenges alpine flowers have adapted to survive in the land above trees providing us with exquisite blooms. Alpine flowers grow low to the ground, protecting them from fierce winds while soaking up heat radiated from the ground. Deep tap roots spreading out to find water and securing to the thin soil also benefit these plants. Most alpine flowers are covered with fine hairs on leaves and stems trapping moisture, heat, and acting as a sunscreen. Damage to these tiny plants could take hundreds of years to recover, if at all. Hike on durable surfaces, rocks, hard-packed dirt, four inches or more of hard- packed snow. When hiking with others spread out like a fan to avoid walking over the same ground. When climbing high peaks stay on designated routes. Braiding trails on peaks causes erosion and loss of alpine flora. Place backpacking tents only on designated sites, keep a clean camp, and avoid removing rocks, dirt, etc. Not unlike a lot of wildflower enthusiasts, I enjoy capturing that flawless photo of my favorite wildflower. I also appreciate the thought that the rare wood lily out in the middle of a wet meadow is more beautiful than the one right next to the trail, but it is not. It is like that one raspberry in the very top of the shrub you must get but instead end up with a painful hand full of thorns. Valuing that flower next to the trail is the best choice. Removing tree limbs or other natural objects for that flawless photo can also be destructive to plants as these natural objects may provide shelter and/or nutrients. Be creative with photographing flowers without rearranging the area that is naturally theirs. I use a Canon power-shot SX40 camera combined long lens with mega zoom that enables me to get photos standing several yards away. I also use an Olympus E- M5 Mark II with an interchangeable macro lens. Consider a pair of binoculars specifically developed to view the minute details of flowers, butterflies, birds Consider a pair of binoculars specifically developed to view the minute details of flowers, butterflies, birds from a distance. A good choice is Pentax Papillion II series. Many years ago, I did not know much about outdoor ethics and I'm sure I may have caused some damage. These days I'm mindful where I place my feet, my hands, my backpack. Being mindful in the natural world takes practice. Here are suggestions to make mud season comfortable for the hikers and safe for plants:

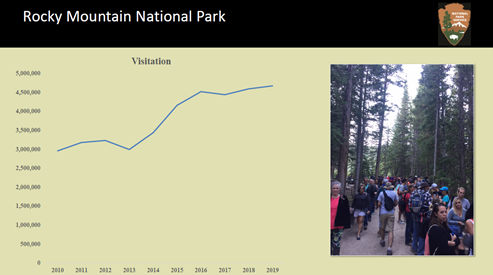

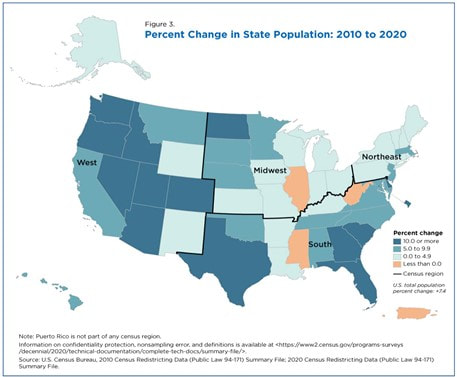

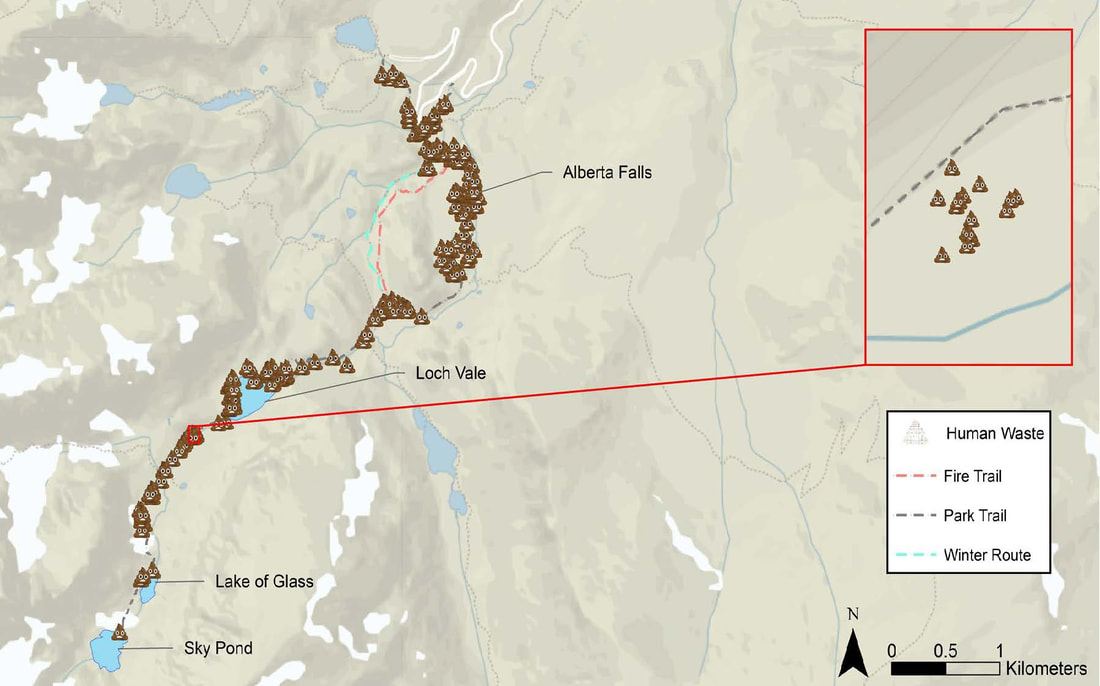

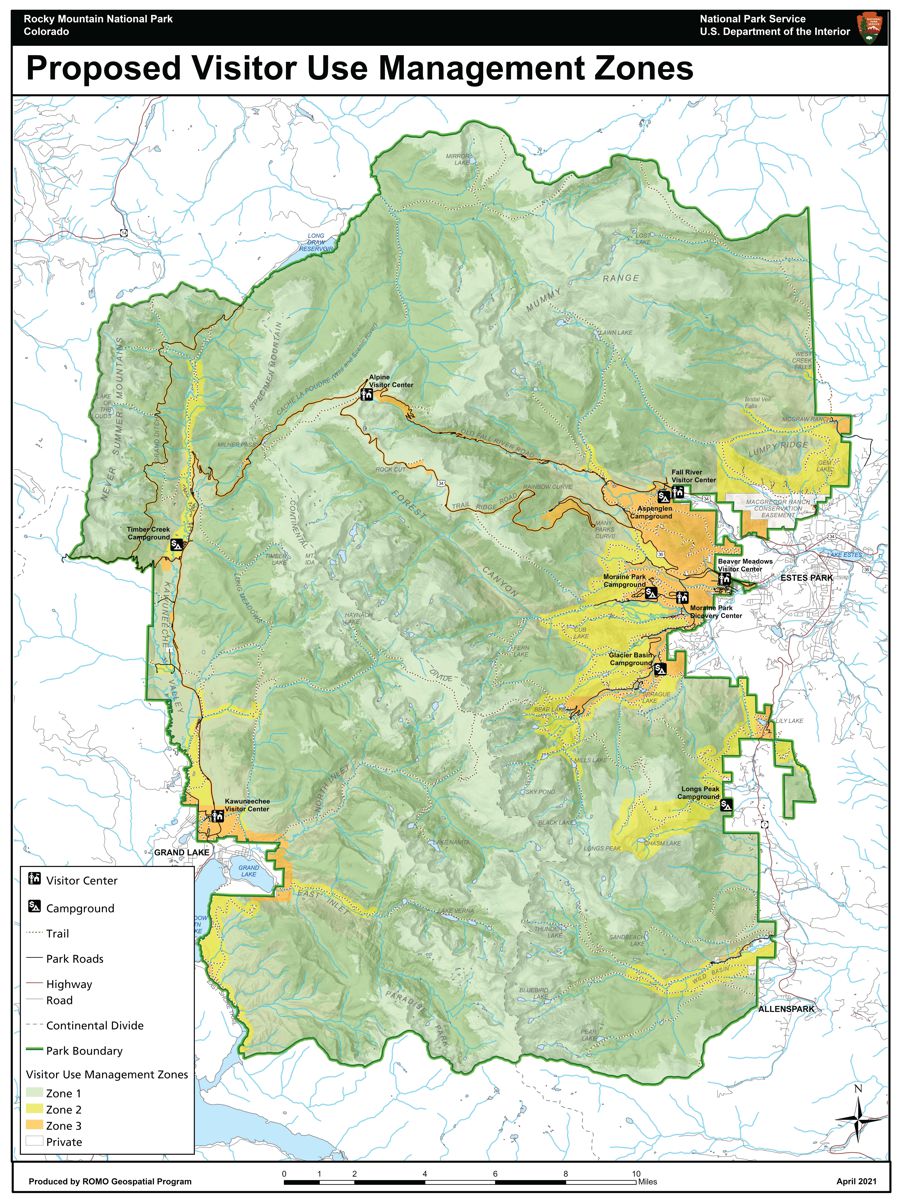

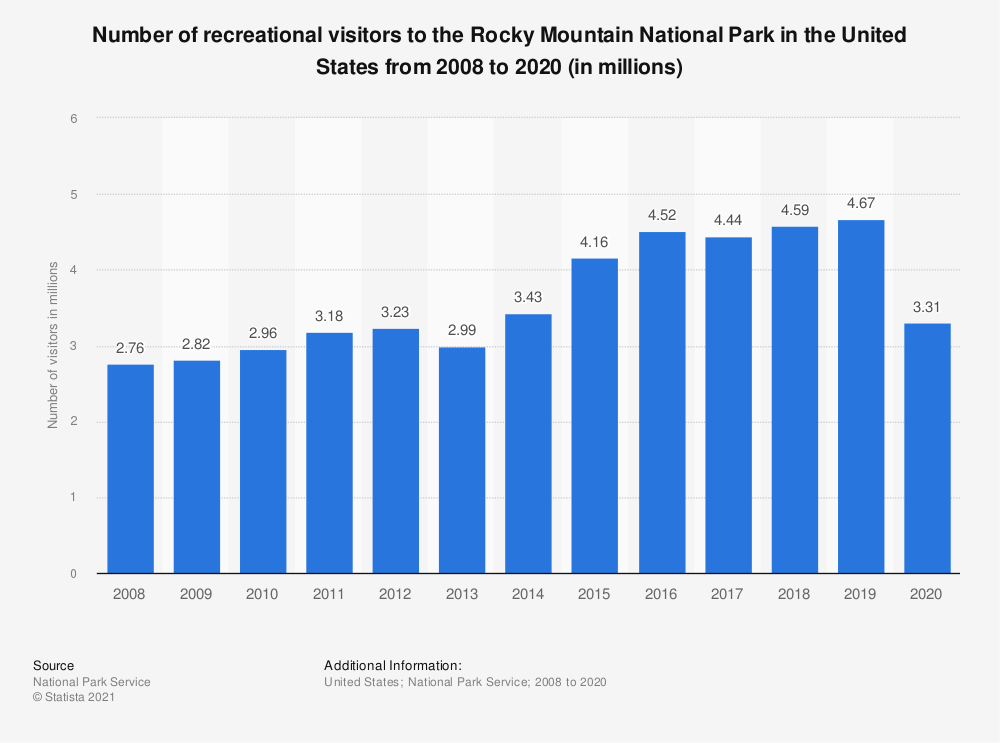

My simple message to wildflower devotees is awareness. Hikers using a mindful lens are truly diligent about protecting our natural world. The reward is a bountiful wildflower season year after year!  Marlene has been photographing Colorado's wildflowers while on her hiking and climbing adventures since 1979. Marlene has climbed Colorado's 54 14ers and the 126 USGS named peaks in Rocky. She is the author of Rocky Mountain Wildflowers 2nd Ed, The Best Front Range Wildflower Hikes, and Rocky Mountain Alpine Flowers. Purchase her books here editor's note: this story is pulled out in its entirety from the February/March edition of HIKE ROCKY digital magazine. For more information about the magazine visit this page by Barb Boyer Buck It's an emergency, calling for emergency measures. The exploding visitation numbers at Rocky Mountain National Park combined with a budget that has stayed flat for a decade has put Rocky's management officials in a defensive position. Something must be done to keep Rocky from being loved to death. “I'd like to say our staffing levels have kept up with the increase in visitation, but it has not,” said Kyle Patterson during a question-and- answer period after a public presentation held on May 25, 2021. This meeting was part of public outreach about long-range visitation strategies in Rocky. “Our base budget that we get from Congress has seen a very flat situation over the past 10 years,” said Rocky's superintendent Darla Sidles at that same meeting. “This flat is essentially an erosion of our budget,” about 14% over that time. Staffing has decreased by 16% as well, while visitation has increased by more than 40% since 2012. Visitation management measures have been in place since 2016 – everything from limiting traffic along the Bear Lake corridor to increased shuttles have been tried to help with the congestion, traffic, inability to find parking, and more. But it wasn't enough; in 2019, the Park's visitation numbers of 4.6 million made it the third most-visited national park in the nation. The following year was a tough one for everyone, but especially for Rocky. The Park was closed for two months between March-May, 2020 due to COVID19, and devastating fires burned more than 30,000 acres (the most in any fire season in the Park's history) from August-October, with dynamic closures of much of the most popular areas of Rocky It was also the first year of timed-entry reservations, a measure that has received a considerable amount of blow-back from the public, especially from those who live near Rocky and along the Front Range. But still, visitation numbers for the year dropped by only 29%, or to 3.3 million visitors. In fact, record-setting visitation occurred in November and December of that year, after most of the Park reopened post-fires and the timed-entry reservation system expired for the season. In 2021, the timed-entry reservation system was modified to address the inadequacies of the previous year's program. Reservations were now required from 5 a.m. to 6 p.m. in the most popular area of Rocky: the Bear Lake Corridor, which includes Bear Lake, Glacier Gorge, Spruce Lake, and Moraine Park and the rest of the Park had reservations-only in place between 9 a.m. – 3 p.m. Even so, visitation for 2021 jumped back up to 4.4 million. The reservation system for 2022 will look a lot like last year's, but it's still considered a pilot program; tweaks were made to address some of the shortfalls of the system that ran in 2021. Reservations will be required from May 27 – October 10, 20, with the first reservations taken on May 2 for May & June dates. “Initially, 25 to 30 percent of permits will be held and available for purchase the day prior at 5 p.m. through recreation.gov. These are expected to sell out quickly and visitors are encouraged to plan ahead when possible,” states Rocky's website. So, those are the nuts and bolts. Not enough funding to improve infrastructure and keep staffing levels where they need to be to properly manage visitation is why we are facing another year of timed-entry reservations. For those of us who live near Rocky and have traditionally been able to pop into the Park when the whim hits us, this can be a hard pill to swallow. The presentation I referred to above fielded questions and collected comments as part of this process; the name- redacted comments are available to read here. They run the gamut from criticizing a lack of privilege for local and Front Range residents to pleas for conserving Rocky's natural wilderness & implementing even more strategies. Some accuse the NPS of a money-making scheme; some say that low-income people will be deterred from visiting. As stated by its Organic Act in 1916, National Park Service's mission is “ to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wildlife therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations." Rocky became a National Park in 1915, but perhaps even more significantly, 95% of its land became designated wilderness in 1974, under the Wilderness Act. Designated wilderness by law meant "...in contrast with those areas where man and his own works dominate the landscape, (wilderness) is hereby recognized as an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain." Why has visitation increased so dramatically at Rocky? The increase in visitation, especially over the past few years, has a direct correlation to several factors. When the pandemic closed off much of the other recreational opportunities available to society, the great outdoors became very popular. This trend pushed those who may have never really visited the outdoors to try it out, which can bring its own problems. Rocky is not at all a “park” like those in urban or suburban areas. Most of it is true wilderness, remote with challenging terrain for even the most experienced outdoorsperson. For example, Rocky has spent an inordinate amount of time pulling vehicles out of ditches this season because the drivers were unfamiliar with driving in winter conditions, or their vehicles were not suitable for the conditions. If the state's traction law is active for Rocky, all vehicles “must have properly rated tires (Mud and Snow, Mountain and Snow or All-Weather Tires) with a minimum of 3/16" tread,” reads Rocky's website on the subject. “If you have improperly rated tires on your vehicle, then you must use an approved traction control device. These may include snow chains, cables, tire/snow socks, or studded tires. When the traction law is in place in RMNP, if a vehicle is involved in a motor vehicle crash, to include sliding off the road due to icy conditions, motorists will be cited if their vehicle does not meet Colorado Traction Control Law requirements.” While overall population growth has stagnated in the US, Colorado's growth has exploded in the past 10 years, gaining nearly 800,000 new residents, leading to another state representative going to Congress. Most of this growth occurred along Colorado's Front Range and Rocky's statistics show that 30-40% of the Park's visitors are from the Front Range. Rocky Mountain National Park's Day Use Strategy Currently, Rocky is working on a long-term day use visitation strategy after its pre-NEPA (National Environmental Policy Act) planning effort and outreach. Additional public comment will be solicited in early 2023 when the formal NEPA process is underway, but the bottom line is that visitor management strategies are here to stay. The pilot programs that have been in place since 2020 will evolve into a permanent strategy based on the results of the NEPA study and other day-use strategies already implemented. Just how restrictive these may be is dependent on funding, staffing, and visitor behavior. The planning process' purpose has many priorities, based on Rocky's mission as a Wilderness Area and a National Park. These include the proper management of the Park's natural and cultural resources, staff and visitor safety, visitor experience, and Rocky's operational capacity. Resource Impacts Social trails, widening of existing trails by visitors, off- trail wandering, and native plant trampling has caused damage to sensitive environments. So has roadside parking, idling, “elk jams” (traffic jams when a wild animal is seen). Vandalism and the illegal collection of artifact damages the cultural sites within Rocky and is “of particular concern to tribal interests.” Human waste has been found in increasing concentrations, affecting water quality and visitor experience. Visitor Experience High traffic congestion at the most popular destinations and roadways has led to frustration among visitors due to the inability to find parking. John Hannon, the Park's visitor use management specialist, reported escalating conflict, including fist fights among visitors and staff, during these times. This congestion has led to the elimination of some popular ranger-led interpretive programs and has impaired emergency response and maintenance of facilities. Even volunteer rangers, desperately needed to help with staffing issues, can't find parking in the places they are needed most. Staff and Visitor Safety Along with physical altercations between frustrated visitors and staff, other safety concerns include visitors illegally starting campfires, approaching, or feeding wildlife, and/or bringing dogs (which are predators to many species) on Rocky's trails. All of these can cause emergency situations that can result in severe injury or death.  Long lines at restrooms prevent staff from properly maintaining these facilities. RMNP photo Long lines at restrooms prevent staff from properly maintaining these facilities. RMNP photo Park Operations and Facilities Higher visitation results in excessive wear and tear on facilities causing the need to triage repairs and focus on the most heavily used areas of the park causing other areas of the park to degrade further. Long lines to get to job sites for facilities, law enforcement, and interpretation staff hampers the park's abilities to provide critical services like maintaining restrooms, responding to emergencies, providing in person program and outreach. Higher water use and wastewater generation than systems can support causes increased frequency and costs of sewage pumping at park-wide vault toilets. Proposed Visitor Use Zones and the desired outcomes of visitor-use strategies In this pre-NEPA process, Rocky Mountain National Park identified three visitor-use zones, each of which are likely to have different visitor-use strategies. Zone One is comprised of 100% wilderness and considered low-use, low-encounter. This area is indicated in green on the map. In this zone is where the natural landscapes are emphasized to their greatest extent. These areas are minimally maintained and provide the best opportunities for solitude and self- reliance. The desired outcome for visitor use strategies in this zone is to keep wilderness conditions pristine, that plant and animal life will thrive with high water quality and minimal human influence and social trails become non-existent. Zone Two provides easy to moderate access to wilderness through Rocky's trail system. These areas are indicated in yellow on the map. and include well- maintained trails closer to restroom facilities, but still provide opportunities to experience the wilderness in relative quiet. The desired outcome in these areas is to keep wilderness recreation plentiful with sustainable trail maintenance and moderately available, well- maintained restroom facilities while retaining the natural integrity of ecosystems, wildlife habitats, and migration behaviors. Indicated in orange on the map is Zone Three, where the most human impact occurs. Envisioned for this zone is that surfaces are hardened or paved to reduce impact on the natural environment and visitors have the most access to information to help them recreate in Rocky and travel with ease to their preferred destinations via private vehicle or alternative transportation. Interpretive and educational programs provide opportunities for visitors to increase understanding and appreciation for park landscapes and resources. The pace of visitation is at a level where park staff can interact with visitors to ensure that visitors are informed, prepared, and use best safety practices. With proper management in this zone, established trails do not exceed design specifications, and visitor- created trails and trail widening are minimal to nonexistent. Visitors experience clean and accessible public facilities, and park staff can access facilities and work areas in a timely manner due to less roadway congestion. Right now, Rocky is still collecting data – the indicators, thresholds, and capacity of the various routes and destinations within its boundaries. In early 2023, the NEPA process will begin, which will give people another opportunity to voice their concerns and make suggestions. Preliminary long-term strategies that are being considered could include a combination of:

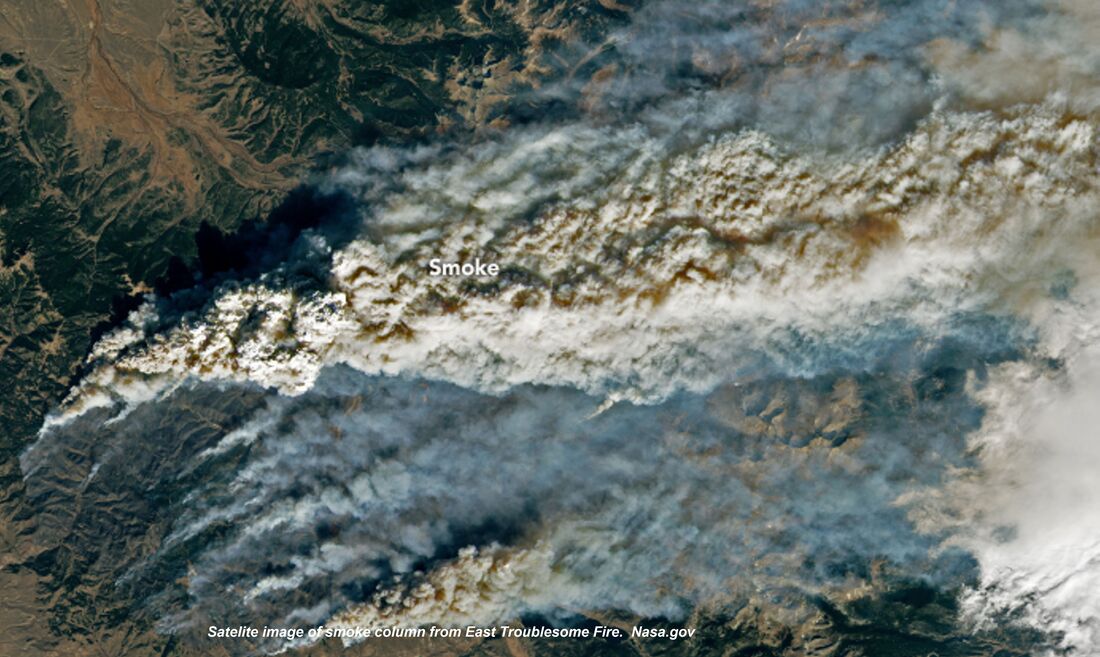

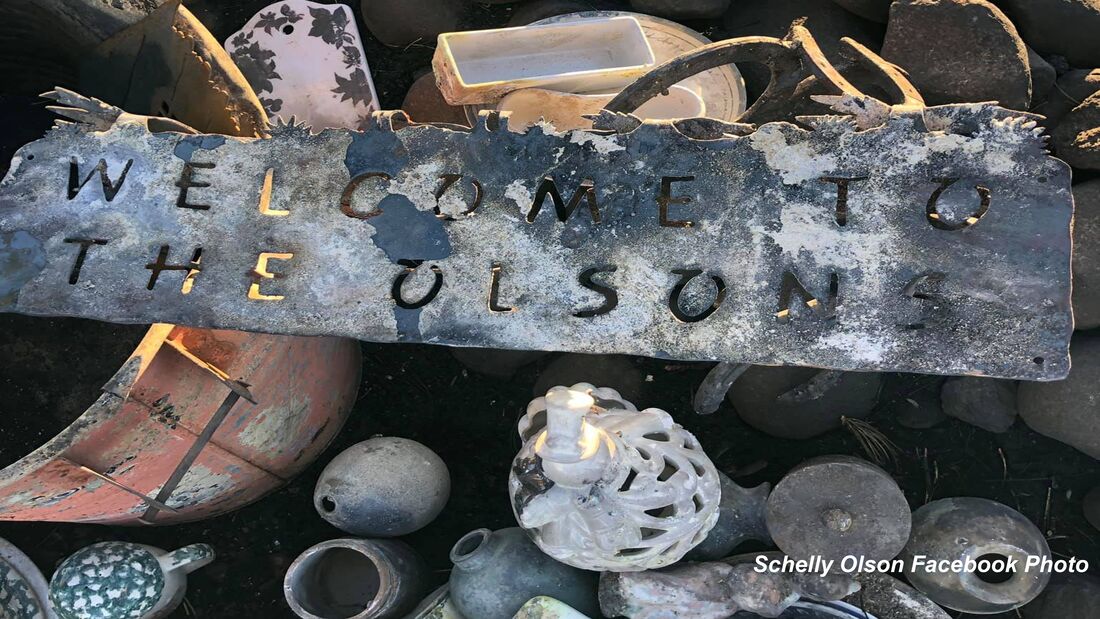

“It's not the Rocky Mountain National Park of the 1970s or even the 90s, unfortunately,” Superintendent Sidle said. “We've been trying some different things over the past six years for how to manage this increase in visitation”, and the timed-entry reservation pilot programs have been a stopgap measure to try to spread out visitation throughout the day. Increased visitation is a nationwide problem; visitor-use strategies are being implemented in several national parks across the nation this year including Acadia, Arches, Haleakala, Glacier, Rocky, Shenandoah, and Zion. “Rocky Mountain is a national park,” said Patterson. “And while so many of us are fortunate to live on its doorstep or moved here because of the Park, we cannot provide special access to locals.”  Barb Boyer Buck is the managing editor of HIKE ROCKY magazine. She is a professional journalist, photographer, editor and playwright. In 2014 and 2015, she wrote and directed two original plays about Estes Park and Rocky Mountain National Park, to honor the Park’s 100th anniversary. Barb lives in Estes Park with her cat, Percy. Lessons learned from Colorado's biggest, wildest fires (part 3)Note: the following story was included in the February 2021 edition of HIKE ROCKY magazine and is being reprinted to accompany the new documentary, FIRESTORMS by Barb Boyer Buck “Hope is not a strategy,” said David Wolf, fire chief for Estes Valley Fire Protection District, about the realization the Cameron Peak Fire, which started north of the Estes Valley on August 13, 2020, could burn straight toward his jurisdiction. “There was nothing but fuel” between the fire and Glen Haven after it jumped Highway 14, so Wolf started preparing for if it came this way. “The day (the Cameron Peak fire) started, we were coming home from Grand Lake, driving through the Kawuneeche Valley and I saw a plume on the horizon,” recalled Kevin Zagorda, chief of the Glen Haven Area Volunteer Fire Department. “I turned to my wife and said, that's fire.” Zagorda thought it may be coming from somewhere in the Never Summer Range, “but by the time we got up Trail Ridge Road and got to Medicine Bow curve, you could clearly see where it was coming from, and that it was big.” Rocky Mountain National Park's fire management officer, Mike Lewelling, started a response in conjunction with the National Forest Service right away. “At first, we thought it was in the Park,” he remembered. The northwest section of RMNP is some of the most remote wilderness in RMNP's boundaries. Lewelling started working with the forest service to pinpoint the fire's exact location, which turned out to be 15 miles southwest of Red Feather Lakes, less than 80 miles north of the communities around Glen Haven, the Estes Valley, and the northern border of RMNP. At first, the fire wasn't moving toward the Park, Lewelling said, so he and his team concentrated on preparing for if it did. “That first week, we were brought into the Forest Service planning efforts,” he said. He and the incident commander for the section of fire that was closest to RMNP flew over the fire to assess. “I wasn't too concerned until I flew over Chapin Pass, and realized if the fire went up and over, that's where our Willow Park cabin is (along Old Fall River Road), and that's the Fall River drainage – which goes right into Estes Park.” Lewelling said they identified a few places along Fall River where they could “maybe make a stand,” but it didn't look like any line they could establish would hold. So, efforts shifted to developing evacuation plans. Even though it hadn't yet reached the Park's boundaries, on August 18 2020, some sections of northwest RMNP were closed. A week later, the Cameron Peak fire made its “second push,” Lewelling said, “and it came into the Park pretty fast.” Due to the inaccessibility of that section of the Park, it was very difficult to pinpoint the exact location, but it was clear the fire was within RMNP's borders. But then, a very early snowstorm hit on September 8-9, one of the earliest snows with accumulation recorded since the late 1800s. This stalled the fire's progression. Over the next few months, the Cameron Peak Fire “didn't want to move south into upper Chapin Creek, the area we were worried about” Lewelling said. They used helicopters to sprinkle the leading edge with retardant, but that doesn't really do much unless ground crews could go in to follow it up, he explained. All they could do was hope the fire didn't move south. More dry and windy weather followed the early- September snowfall and crews continued to work the Cameron Peak fire over the next six weeks as it burned toward communities northheast of the Park, including Glen Haven. “We had become a Fire Wise community in July,” GHAVFD Chief Zagorda said; as soon as the fire started, the communities in the Glen Haven area began to prepare. “A lot of the property owners had done significant mitigation work before the fire even began, which was a big plus for us,” he said. “We also had updated our Community Wildfire Protection Plan earlier that year.” A volunteer organization, Team Rubicon, contacted Zagorda about doing mitigation work in the Glen Haven area earlier in 2020. Team Rubicon is a veteran's organization that provides humanitarian and recovery aid to communities all over the country. “We took a look at our vulnerabilities and knew we were vulnerable in any of the drainages (ie, Miller Fort, North Fork, West Creek), so we knew we wanted to do some thinning of trees and other mitigation work toward the edge of developed areas.” An area in the North Fork drainage was completed and an area around the Retreat was partially completed, Zagorda said. “And then, a couple of weeks before the fire, Larimer County contacted me. Their fuels crew wanted to come up and do some work in Glen Haven.” They were going to finish the area around the Retreat in September. But by then, everyone was engaged in actively fighting this fire, which ended up burning 208,913 acres in Larimer and Jackson counties, making it the largest wildfire in Colorado's history. On October 14, the Cameron Peak fire made a “pretty big run on a red-flag day, I think it was a 12-mile run, that fire came down Panic Pass and down the Miller Fork drainage and got into the Retreat, just outside the developed areas.” But where Team Rubicon did fuel reduction, “it took a lot of the punch out of the fire,” Zagorda said. As a result, and with a little help from the weather which had turned cold again, his team was able to battle the fire directly in those areas, keeping it away from homes. This effort was bolstered a lot by the mitigation work the property owners had done, earlier that year. “I sat up there at the lookout point and watched the fire coming down the hill. It was very smoky, you couldn't see very much, but I was convinced a lot of those homes were going to be lost. As the smoke began to clear, you could see the fire come down and burn around the houses, because of the mitigation work the property owners had done,” Zagorda reported. Another thing that helped prepare for this fire was a community workshop on how to develop an evacuation plan, held by the department in August. GHAVFD and EVFPD helped Larimer County with evacuations and then got quickly to work on “rapid structure protection,” Zagorda explained. In about five minutes at each property, the crew worked to remove all combustibles away from the house did some quick chainsaw work on vegetation, and sprayed a little fire- fighting foam. “And then we had to back out and wait for the weather to cooperate before we could fight the fire directly.” The community of Glen Haven lost one home and three second homes. Several building and outbuildings were lost as well. No human or animal lives were lost in this area. The fire came within one-third of mile from Zagorda's house; he and his wife were evacuated for three weeks during which they moved seven times. Interagency cooperation and joint efforts are extremely important when fighting wildland fire, and with training efforts. Chief Wolf from the Estes Valley district, led a strike-force commander training session earlier that year which Zagorda credited as being very valuable during this fire. “Estes Valley and Glen Haven have a very good working relationship, we are mutual aid partners and we train together,” he said. Type I incident command teams arrive at big, dangerous fires – they are made up from crews from all over the country and serve about 2-3 weeks before another team is deployed. When they arrived at Glen Haven, they helped with setting up sprinkler systems for structure protection, bringing that equipment from the Red Feather Lakes area. Lewelling's crew began efforts in the Glen Haven area at about this time, too – the National Park was now on fire near its northeastern border, burning around Signal Mountain before back-burning about 300 acres into RMNP land and threatening the North Fork ranger cabin. “Make friends before you need them.” Lewelling got this piece of advice at the beginning of his career and with firefighting, it's absolutely essential. Wildfire doesn't respect jurisdiction lines and interagency cooperation and communication is key to successful fire management. The same day the Cameron Peak fire made its epic run toward the communities surrounding Glen Haven, the East Troublesome fire began on the west side of the Continental Divide. Along with serving as the assistant chief of the Grand County Fire Protection District 1, Schelly Olson is a public information officer for for fire incident teams, going out on fires all over the country. Many times, she is not necessarily working local fires; in fact, that summer she had been on a couple of fires in Arizona and then the Williams Fork Fire, 10 miles southwest of Fraser. “I had been on the Williams Fork fire for almost 50 days,” Olson said. She and a friend from Eagle County, also a PIO, needed some rest so they bought plane tickets to take a short vacation in Florida. The forest service called on October 14 to see if Olson could be PIO for the East Troublesome fire, but she declined because she had already booked the tickets. “I felt tremendous guilt because here was a fire in my county, and I'm leaving. “I did not know what (the East Troublesome fire) was going to do,” she said. She was still in Florida when the fire blew up the following Wednesday. It had been a tough fire season for those in Grand County, reported the Grand Fire Protections District 1 chief, Brad White, with multiple fires in the region. “Most of us lived under smoke clouds the entire summer,” White reported. Centrally located near Granby, his crew is often called out for interagency work as well. But when the East Troublesome fire started, White and seven other members of his crew were on quarantine for a known exposure to someone with an active COVID infection. The chief was working from home when he got a call from the Grand County sheriff, wanting to put part of White's district under a pre-evacuation order– the fire had burned 3,800 acres that first day. “Well, I said that's fine but I want to get a look at this fire myself.” After he assessed what the fire was doing, he contacted the sheriff and advised evacuation zones needed to be established all the way to Highway 34. There are a total of 5 fire protection districts that serve Grand County which is 1,870 square miles in area. They all perform mutual aid within the county, and with federal land management agencies - the forest service and national park service. The incident command team that had been dispatched to the Williams Fork fire stepped up as well. “October is a bad time of year to try to get federal resources so the (incident command) team was already thin. But not only did they agree to take on this new fire, they agreed to stay an additional week,” White said. Over the next couple of days, the fire grew from near Kremmling to the Hot Sulphur Springs area. On October 19, the wind started picking up again. “It was a pretty active few days, with air tankers dropping slurry,” White remembered. On the morning of the 21st, crews predicted the fire might cross Highway 125, where a few homes and ranches were located, so all those people were evacuated. “We felt pretty good because the fire was moving rapidly, but it was moving northeast toward Gravel Mountain,” away from more populated areas in an area where the fire could be boxed in. The mountain area mutual aid group (MAMA), which had been formed several years prior with 10 other Colorado counties, had been contact to help expedite resources and help with the evacuation of the Trail Creek subdivision, located off County Road 4 west of Lake Granby. But around 7 p.m. on the evening of the 21st, White realized something different was happening. “It got really dark up there,” he said, “the smoke column settled down and the winds really picked up.” From about 7-8:30 pm MAMA was involved in evacuations throughout the district and then started to try to protect structures. Similar to what Chief Zagorda and his crews were doing in Glen Haven, these crew members tried to save homes by removing combustibles from around the homes that were threatened. “At one point, I figured out the fire had traveled 17 miles in 90 minutes,” White said. “That's not the kind of fire you put fire fighters in front of.” In Grand County, “we lost 366 homes and I'll bet we lost 300 of them in that first big blow-up.” Meanwhile, back in Florida, Olson's phone was blowing up with calls from people asking where she was, how they should evacuate, etc. She was also receiving evacuation notifications for her home. “My husband was home alone and he wasn't signed up for emergency notifications so I relayed them to him,” she said. Because the fire blew up so quickly, he had about 10 minutes between the pre-evac notice and mandatory evacuation orders. “He was not able to pack up anything, only get himself, some clothes and our dog Rambo out,” she recalled. “I found out about the house at 2 o-clock in the morning, “We had a very large heavy-timber solid log home – the logs were 24 inches in diameter. Very hard to burn.” But nevertheless, the house burned to the ground, a complete loss. Olson's husband, Jeff, reported he could see the orange glow, feel the heat and extreme wind, and that it sounded like a freight train coming toward him, just prior to his evacuation. “Our house sat on the top of a hill and right behind us was a golf course. In front of us was the road, and on the other side of the road was marshy swamp land and then the Winding River Ranch. The ranch was a huge open space, no trees, only grass.” A few of the homeowners including the Olsons, had removed trees closest to their structures for a buffer, “but obviously, none of us had enough of a buffer.” The surrounding terrain, which logically should have provided fire breaks, didn't help either. Olson explained why: “The wind blew giant embers ahead of the fire. Everything was pre-heated because of that hot wind. Fuel can start combusting, even without that direct- flame impingement. The embers just showered down and landed on everything,” Olson said. In other cases, windows were blown out and embers got inside homes, burning them from the inside out. “The engine block that was in the car in our garage just melted onto the concrete floor, creating what looked like a sculpture,” she said. All of her jewelry was pulverized by the extreme heat. Meanwhile, on the east side of the Divide, Lewelling was discussing evacuation plans for Park personnel with the district ranger in the Kawuneeche Valley. “When she told me the fire was at Sloopy's – the burger joint just south of the Park - it really hit home.” Park personnel stationed on the west side of Rocky evacuated over Trail Ridge Road and reached the emergency command center at midnight– where Lewelling, Wolf, and many other officials were coordinating efforts. “A big part of this story is what you see in people's eyes,” Lewelling said. “We're all professionals with many years of experience, but you could see it in people's eyes – this was different. This was a different event.” Lewelling thought that was all that was going to happen for the night. “Certainly, it wasn't going to cross the Continental Divide,” he thought. But first thing in the morning of the 22nd, he got a call from the National Weather Service, telling him weather satellites detected a heat signature on the east side of the Divide. “From how much the wind could blow the smoke column, that signal could just be embers in the smoke column. It doesn't mean there is fire on the ground,” Chief Wolf said when he first heard about the weather satellite's detection. Mid-morning, it became clear the fire had indeed jumped the Divide and was working its way to the Fern Lake burn scar. Around noon that day, the emergency management team started working on an evacuation plan for the Highway 66 corridor. It was still not clear how far the down the fire had gotten down into the east side of the Park because of the heavy smoke that was billowing out in front of it. By the time it was confirmed, the fire had reached Mount Wuh and had already blown past one of the evacuation triggers, Wolf said. The triggers were set by a joint emergency management team in 2017, which predicted what would happen if a fire which started in Rocky got into one of the drainages leading into the community of Estes Park. These models predicted such a fire under worst-case scenarios would burn through the town in four hours. The current situation was worse than any scenario imagined. It was time to act quickly. By 2 p.m., for the first time in history, the entire Estes Valley was under a voluntary evacuation order; by Saturday, October 24, the order was upgraded to mandatory for everyone in the valley. “Since law enforcement was handling the evacuations, we were able to focus on other priorities, such as protecting our communications, the hospital, and long-term care facilities, knowing that they would need more time for evacuations,” Wolf explained. Another concern was the water supply. “We knew that the number of resources we had were not going to be enough for the fire fight we were expecting,” Wolf said. Emergency management called out for more resources and were rewarded with a lot of assistance from communities along the Front Range. Saturday night, the local crews could finally have a night off. But at 2 in the morning Sunday, they got another call – a structure fire, unrelated to the wildfires, burned down a home. Sunday morning, everyone was happy to wake up to snow, Wolf said. But now that electricity and gas had been turned off to all the valley's structures, there was a danger of freezing pipes. So, crews helped to winterize homes, and get pilot lights re-lit. The planning that occurred in 2017, organized by Lewelling and Wolf and with the input of many other emergency management personnel was extremely useful during this event, Wolf said. “We thought we would be fighting fire on Elkhorn Avenue by the end of the day,” Wolf said. Luckily, that wasn't the case. “Overall, when we look at what happened with the Cameron Peak and East Troublesome fires, I would say that we were very successful. We were also very lucky,” Wolf said. Efficiency in interagency coordination and cooperation, planning for worst-case scenarios, and effective mobilization of resources was a lesson already learned by Zagorda, Wolf, and Lewelling, thankfully. But one thing that they hadn't thought of is where they would get food- they had just evacuated everyone, including the grocery stores and restaurants. For Chief Zagorda, the fuels mitigation work conducted by volunteers and homeowners saved quite a few homes. Asst. Chief Olson said that one of the lessons learned was to install reflective house numbering, so addresses can be found quickly in an emergency. “Grand County is ground zero for the pine beetle infestation,” which killed 95% of the lodgepole forests, she said. “Fuels mitigation is a big part of this.” Prescribed fires and fuel reduction in Rocky was instrumental in keeping the fire west of the Estes Valley, several of the fire management professionals noted.

All of the fire agencies who were approached for this article depend heavily on volunteers, there are very few career fire- fighters. In areas such as Glen Haven, a non-incorporated community in Larimer County, “every pair of hands and feet were working to fight the fire,” Zagorda said. Both of these fires ended up burning approximately 400,000 acres in northern Colorado; the East Troublesome came in just behind the Cameron Peak fire to be the second largest fire in Colorado's history. Within Rocky's boundaries, 30,000 acres were burned – more than in any other in its 106-year history. Both of these fires, along with most of Colorado's wildfires in 2020, were human caused; the exact causes are under investigation. Since wildfire isn't going away, it's clear the biggest lessons learned from these fires is that the general public needs to become more educated on their responsibilities while recreating in the wilderness Each of these agencies provide community resources on their websites. Visit the Glen Haven Area Volunteer Fire Department at www.ghavfd.org Schelly Olson has created a nonprofit organization called the Grand County Wildfire Council: bewildfireready.org/ Grand Fire Protection District 1 can be found at grandfire.org/ The Estes Valley FPD's website is: www.estesvalleyfire.org/ Rocky Mountain National Park's fire management office can be found here: www.nps.gov/romo/learn/management/firemanagement.html Cover Story for the October 2021 edition of HIKE ROCKY magazine “I cannot endure to waste anything so precious as autumnal sunshine by staying in the house. There is no season when such pleasant and sunny spots may be lighted on, and produce so pleasant an effect on the feelings, as now, in October.” - Nathaniel Hawthorne, from The American Notebooks story and photos by Marlene Borneman Just as wildflowers blooming in summer bring us joy, autumn brings fresh pleasures. The most recognized natural fall spectacle in Colorado is the changing colors of aspen leaves. Quaking aspen, Populus tremuloides, is a hardy deciduous tree native to North America. The leaves are small heart-shaped with fine serrated teeth on the edges. The white bark is smooth which becomes rutted and uneven with age. Deciduous trees lose their leaves each winter. But it all begins in summer when there is an abundance of sunlight which aspens use along with water and carbon dioxide to produce oxygen and energy in the form of sugar. This process is known as photosynthesis. The green pigment chlorophyll is responsible for the absorption of light to help produce the energy (sugar) and hides the yellow, oranges, reds, that are true colors of the leaves. Many internal chemical changes occur in aspens during the fall. At the autumnal equinox and during the days following, there is less sunlight which results in leaves making less sugars, thus less chlorophyll is needed. The trees stop storing sugars and go into a dormant state for the winter months. When this process starts to happen, the pigments carotenoids and xanthophylls become visible bringing out yellow and orange colors.  Detail of an aspen leaf in transition Detail of an aspen leaf in transition So, what about aspens that turn a brilliant red? Less sunlight also signals the aspen trees to form a blockage layer (called the abscission), preventing any sugars from passing between the leaf and the rest of the tree. During this process sugars may get trapped inside the leaf when the abscission layer is being formed producing the pigment anthocyanins. The higher the concentrations of anthocyanins, the deeper the crimson red hues. Each year aspen trees can produce a different set of colors depending on conditions in the environment during the formation of the abscission layer. Elevation, temperature, and moisture are variables that influence the timing of leaf change and intensity of color. The ideal circumstances for a brilliant display are sunny days and cool nights.  Snow plow operations in late September on Trail Ridge Road Snow plow operations in late September on Trail Ridge Road A great way to drench yourself in autumn gold is with a backpack trip to the west side of Rocky. My husband, Walt, and I planned a trip to Lake Verna the day before the autumnal equinox in hopes of catching some colors. The day before our trip, a fast-moving storm system deposited snow, closing Trail Ridge Road for a few hours. We checked the status of the road the morning of our drive to find it had re-opened. Rocky Mountain National Park is full of surprises so take seriously the posted signs that read “Be prepared for rapidly changing weather.” The road up high was snow covered and icy with seventeen degrees at the Alpine Visitor Center! After passing a snowplow, I thought to myself no winter boots, no gaiters, and no micro-spikes. And maybe, no backpack trip. Dropping down into the Kawuneeche Valley, we found a pleasant surprise: only a scattering of snow on the mountains and a balmy forty-eight degrees in Grand Lake.  The author at Lone Pine Lake The author at Lone Pine Lake  Adams Falls Adams Falls The trail to Lake Verna begins at East Inlet trailhead. The first hint of the stunning scenery on the East Inlet is Adams Falls, only 0.3 mile from the trailhead. From here, the trail rises moderately following the creek until reaching switchbacks. Then the trail becomes steeper as it leaves the creek. The East Inlet trail is a good example of trail crews' hard work with many rock steps, fine bridges and retaining walls for hiker's comfort, safety, and prevention of erosion. Soon we are immersed in deep golds, bright oranges, and reds of aspens. By the time we reach Lone Pine Lake it is a warm, sunny autumn day! At about 10,600 feet we see snow lingering in the trees with heartleaf arnicas still in bloom. Another surprise. Lake Verna is the largest along a chain of five lakes in the East Inlet drainage. The old-timers in Grand Lake used to call these the String Lakes; Lone Pine Lake, Lake Verna, Spirit Lake, Fourth Lake and Fifth Lake. There are eight backcountry camp sites along the East Inlet Trail. In past years we have snagged Lake Verna site but this time we are at Solitaire, 6.2 miles from the trailhead. After setting up camp we head for an evening tour of picturesque Lake Verna. Legend has it Lake Verna was named for the sweetheart of a member of the U.S. Geological Survey. The identity of the survey, surveyor and the sweetheart is unknown which makes for good storytelling around camp. The landscape seems so still and quiet as it slowly transitions from season to season.

All along this drainage many stately towers and pinnacles rise above the lakes making a dramatic scene. At 10,300 feet Spirit Lake glistens under the rock tower known as Aigiulle de Fleur which can render one speechless with its hefty but graceful presence. Fourth Lake is next on an unimproved trail with many huge down trees to negotiate over and under. Some of the down trees are the results of a derecho last September before the Troublesome fire raged through the park. Derecho is a type of windstorm with straight- line wind damage in a swath over a large area. The unimproved trail gets very faint after Fourth lake and almost non-existent to Fifth. Remote and striking Fifth Lake sits under the stately towers of Isolation Peak and along the ridge of The Cleaver. Marlene has been photographing Colorado's wildflowers while on her hiking and climbing adventures since 1979. Marlene has climbed Colorado's 54 14ers and the 126 USGS named peaks in Rocky. She is the author of Rocky Mountain Wildflowers 2Ed, The Best Front Range Wildflower Hikes, and Rocky Mountain Alpine Flowers. Snowy Peaks Winery in Estes Park is a supporter of HIKE ROCKY magazine and sponsors the publication of this story.

|

Categories

All

|

© Copyright 2025 Barefoot Publications, All Rights Reserved