|

Notes from the

Trail |

|

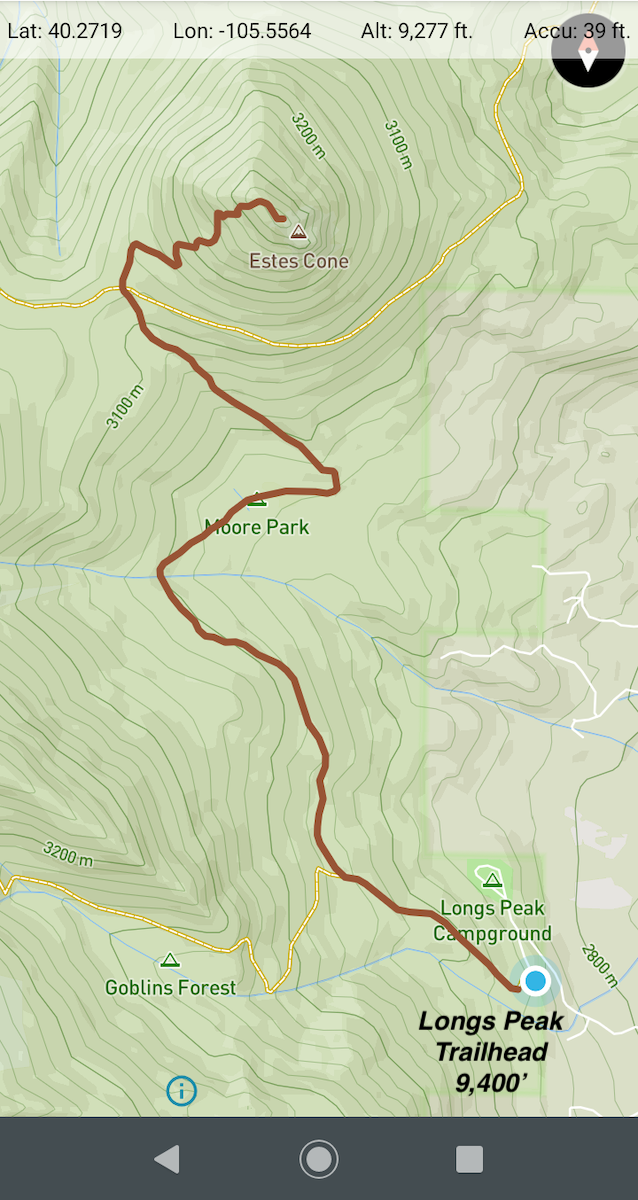

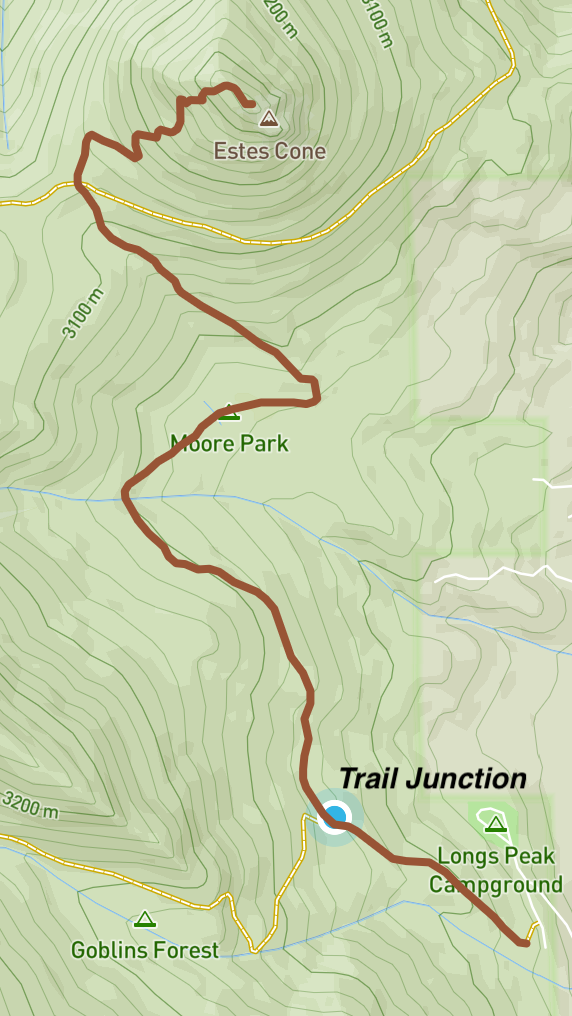

by Ally Anderson Physiology and Medical Sciences UA Franke Honors College University of Arizona “The mountains are calling and I must go." This is a popular quote by John Muir that rang true for a young college student named Ely Bordt. His first experience traveling to the Rocky Mountains pulled him in and never let him go. The Rockies challenged him and changed him, teaching him what his mind and body are truly capable of with enough grit and enthusiasm. It all started the summer of 2017 when Ely participated in a Colorado Ecosystem Field Studies program. The field study website describes this experience as ”An opportunity to study the Colorado Rockies and apply your classroom and textbook learning while immersed in an incredible mountain ecosystem setting.” After that first taste of living and working in the mountains, Ely's life trajectory shifted as he felt a strong pull towards the mountains postgrad. As a wide-eyed college graduate, Ely jumped at the opportunity to trade the flat lands of Indiana for the Colorado Rockies. Flashforward to February of 2021, Ely got a job in Longmont, Colorado and made a point to be on a trail whenever he wasn't working. Having no prior experience hiking or climbing, Ely would often hit the trials with the sole motivation of good views and impressive photos. This all changed when a year later he met his mentor, Kevin Rusk, a seasoned mountain climber with a big heart to show Ely the joy of pushing his body to new heights in the Rockies. Kevin taught Ely how to use his gear to climb in different terrains and instilled in him the importance of precautionary measures like bringing a rope even if you don't think you’ll need it. Ely followed Kevin's footsteps all winter, learning to climb glaciers, starting at their first climb together up Tyndall Glacier. When that winter was over, they climbed rocks together through the summer. “(Kevin) thought, let's get you off a trail and into some ropes, and since then... It erupted and now I'm snow climbing, rock climbing, and scrambling and don't so much stick with trails anymore, I aim to get off the trails.” -Ely As mileage started to increase and he started to fall more and more in love with the mountains, Ely went from a novice climber to someone whose mind revolved around getting back into the challenging terrain of the mountains. Rocky Mountain National Park and the Indian Peaks south of the park became his favorite spots in his early years of serious climbing. He worked tirelessly to condition his body to handle even the most advanced terrain alongside his mentor Kevin. How is it that in only a few short years, Ely has managed to completely shift his lifestyle from somewhat sedentary to extremely athletic? What are the physiological implications that come along with the ability to sustain endurance and strength while clinging to the side of a mountain? How does Ely fuel and train his body to perform at such a capacity? Shift in Lifestyle and Mental Headspace Ely has not always been able to casually climb Longs Peak. Longs is a challenging 14er that requires great deals of mental and physical toughness and is a great achievement for those who complete it. Ely has joyfully completed this climb multiple times and has plans to climb it again! This kind of ambition and ability to take on such challenges illustrates the dramatic shift from how he held himself in his childhood. He explains his early years as a period of time when he was overweight and lacking motivation to keep a consistent exercise regime due to a lack of excitement towards most types of physical activity. ”Prior to hiking, I was a gamer. I spent a lot of time online. There's a lot of toxicity online. I didn’t get out much. Hiking allows me to clear my mind.” - Ely He was an uninspired kid, most often seen indoors playing video games, lacking the desire for exploration or challenging physical feats. Fast forward to the present day, Ely is calmer and more mellow, feeding off of the serine mountain landscape he surrounds himself with. He's a social young adult, full of ambition and he credits this dramatic shift into a more positive headspace to the mountains. “I was entirely unathletic prior to that (moving to Colorado), it was a big change. The views drive me to get out but more so, if I go too long without the mountains, I'm thinking, I need to get a workout in. I need to get active.” -Ely “The mountains are something I get hungry for if I go too long without” -Ely Ely explained how he's tried weightlifting and cycling, but the mountains are the first and only thing that he's seen dramatically motivate him to get active. He has gone from an unmotivated child to a driven athlete looking forward to the next adventure, overall more enthusiastic and motivated about life as a whole. Why Does Exercise Improve My Headspace? As Ely experienced firsthand, there is a link between a lifestyle that prioritizes physical activity and improved mental headspace. The moment someone participates in physical activity, there are neurochemical changes that start taking place. There are hormones directly correlated to stress, which are reduced upon an exercise induced increase in heart rate. As these stress hormones are reduced, chemicals in the brain called endorphins are increased. Endorphins act on the body to brighten a person’s mood and alleviate stress. These chemical changes happen every time a person is physically active and even more consistently in someone who has a habit of increasing their heart rate through exercise. This explains why Ely’s attitude and outlook seemed to transform completely as he became more active. He began to alter his brain chemistry as a whole! Building Cardiovascular Stamina On top of building mental endurance, Ely has also been on a journey of building cardiovascular stamina. This is the ability of the heart and lungs to endure longer and harder through difficult exercise. Coming from an inactive lifestyle in Indiana, Ely describes this as a significant challenge. He started training on lower elevation trails in the Boulder Colorado area and built up to the challenging elevations of the Rocky Mountain National Park. Ely noticed improvements in his cardiovascular capacity when he got out into the mountains as much as possible getting as high as possible! He would celebrate each landmark climb at a higher elevation, constantly pushing himself to get higher and on more challenging trials. Training at Altitude A very common strategy among athletes is training at higher altitudes to develop stronger cardiovascular endurance because of the cardiovascular challenge of being in low-oxygen environments. Something special happens to the body’s ability to carry oxygen when someone puts themselves in a high-altitude environment where the oxygen is thin and less abundant. The low amounts of oxygen trigger a hormone called EPO (erythropoietin), which stimulates the production of red blood cells. The red blood cells begin to grow larger and increase in number to maximize the amount of oxygen they can hold and transport throughout the body. Ely, being an elite athlete who spends the majority of his time exercising at high elevation, has red blood cells that look differently than those of an athlete at sea level who has an abundance of oxygen in the air around them! If Ely were to go down to sea level, theoretically, he would find that his cardiovascular endurance would be even better. He has such a high number of red blood cells at a greater volume ready to make the most of little amounts of oxygen but finding that at sea level there is more oxygen to use than normal. It is very common for athletes to train at high altitudes to change their red blood cell composition and come back down to sea level with an advantage. Fueling the Body to Endure the Mountains Once Ely became more acclimated to the high elevation of the Colorado Rockies he was able to withstand more difficult trails mentally and cardiovascularly. He started to push the limits of what his body was able to achieve and to do so, he needed the right fuel. This meant taking nutrition to a whole new level. Ely describes his diet as high protein and high carb to have energy to perform at challenging levels, restore muscle, and maintain strength. Ely has a specific diet the day before a big hike. He prioritizes water, drinking four liters throughout the day before his planned day in the mountains. He also prioritizes eating as many calories as he can: chips, queso, whole pizzas, you name it. Ely expressed that the biggest component of waking up with energy is drinking substantial amounts of water the day before. While he’s out on the trail, Ely focuses on his sugar intake: fruit snacks, Honey Stingers, and salt tablets with and without caffeine. Ely is slightly anemic, meaning he has a blood disorder that reduces the effectiveness of the blood stream's ability to carry oxygen. To combat this, the morning of a big day in the mountains he will eat two servings of dry Cheerios. This cereal contains 70% of his daily iron intake. Consuming great amounts of iron translates to an increased amount of hemoglobin and an increased amount of oxygen capacity in the mountains. He eats these Cheerios without milk because milk inhibits iron absorption when eaten in conjunction with iron. Importance of Good Nutrition Ely's methods of fueling his body before and during athletic activity are widely used by athletes performing at his level of difficulty. His emphasis on water intake the day before extreme physical exertion is very important, especially on a hot day where perspiration is more likely. Water is important in so many aspects of body functionality including regulation of body temperature, lubrication of the joints, and transportation and digestion of important nutrients. Adequate levels of hydration affect many aspects of athletic performance. Carbohydrates are used by the body as its main fuel source during any kind of energy expenditure. Having a plentiful store of carbohydrates for the body to use will supply more energy and allow it to endure harder and longer. Nutritionists also recommend athletes prioritize snacks throughout the day, as Ely does, to maintain energy and nutrition, keeping the body strong and able to endure. What is Next for Ely Bordt in the Mountains ”My biggest challenge is just bravery” -Ely In past summers, Ely has done a lot of fourth-class scrambling. His goal for this summer is to get into more low fifth-class scrambling. This is the kind of terrain that borders the need for a rope. He aims now to challenge himself on more difficult terrain that is intimidating and more technical. If it is at all possible to be done without a rope, that's the way he wants to get it done. Ely does prioritize his safety, carrying with him what Kevin taught him in the beginning. “When I talk about getting into these technical terrains being my goals next summer, I always go in with what he (Kevin) taught me about having an exit strategy. I'll probably bring a rope and even if I don't use it on the way up, if I get cliffed out and need a way to get out of what I'm on, a rope will always be handy for at least rappelling and getting off.” -Ely Ely wants to get in the right mental space to be able to handle harder terrains such as the north face of Longs Peak. “I can see the goals I had and met, and I'm now wondering what I can do next” -Ely

0 Comments

Summer hiking season is fleeting and from the early days of summers warmer weather, a panic can overtake me that I won't get enough days on the trail before it's all over. It can feel hectic to make the time, make the reservations, set the alarm for early arising, hurry through the gate to get on the trail and get to the long planned destination, so that I can finally relax! A day on the trail is the best, but sometimes in the rush to get as much hiking as I can, I can feel as rushed on the trail as I do off the trail and I forget to slow down. The days of August can be the best days to practice taking time to slow time on the trail. It can be a time of nature immersion.

Immersion Tips

Don't hike. Instead feel what it's like to saunter or meander. It can be easier if done alone, but if you are with others, talk about what you hear, share interesting nature patterns you see. Speak through nodding. Don't plan on a destination. Instead find places to sit, close the eyes, and listen. Listening to the sound will make it easier to not think about everything else going on in your day to day life. It's the way to slow time. Though it can be difficult in busy Rocky Mountain National Park to become fully immersed, try going in the evening, when there are fewer people on the trails. Three trails for immersion While almost any trail can lend itself to immersion, here are three to practice on:

Coyote Valley

Copeland Falls

Take advantage of these late summer days to practice slowing time with an immersion in Rocky Mountain National Park. By Jamie Palmesano Ansel Adams, America’s most famous photographer said, “You don’t take a photograph, you make it.” Making photos is one of the most delightful parts of hiking Rocky Mountain National Park. We live in an age where nearly everyone now carries a camera in their pocket. Whether you have a DSLR or an iPhone, a few tricks of the trade can help you create outstanding photos to commemorate your hiking adventures. These are my favorite five tips for creating powerful scenic images and capturing the grandeur of the Rocky Mountains. With each tip, there is a photograph to demonstrate how that photography rule looks in real life. RULE OF THIRDS The Rule of Thirds can help you compose a well-balanced photograph. Imagine that your image is divided into nine equal parts by two vertical and two horizontal lines. You want to position the most important elements of your image along these lines or at the points where these lines meet. This will create a wonderful balance to your scene and highlight the key features of your image. LINES LEADING TO INTEREST When we look at a photo, our eyes are naturally dawn along lines. It’s how we see. There are lines everywhere around us, whether they are fences or sidewalks or trails or trees. If you place these naturally created lines within your photograph to lead to a point of interest, it will pull the viewer into your image. Leading lines can take you toward a subject or even move you through a scene. POINT OF VIEW The point of view or perspective may be the most influential tool used to create a powerful image. Just like in life, how we see a situation will determine our success or failure. Often, if we simply change our perspective, we see a situation through a totally different lens and find treasures, even in difficult situations. In photography, the point of view has a significant impact on the composition of our photo. It truly determines the message we convey with each image. Rather than just standing there and pointing your camera in front of you and shooting at eye level, change your perspective. Consider laying on the ground, climb a high rock, move to the side, get close up or zoom way out. Play around with different angles. Make your photograph tell a story by showing the object from a different vantage point. FRAMING There are natural frames everywhere we look. Trees, archways, branches, holes in rocks all create natural frames by placing them around the edge of a composition to isolate the subject from the rest of the image. A more focused image will naturally draw your eye to the point of interest. The frame will highlight the main subject in a photograph. This tip works in tandem with point of view because oftentimes you will need to change your position to locate these natural frames. BACKGROUND Our human eyes can seamlessly distinguish between different elements in a scene, but the camera struggles to do this. A camera has a tendency to flatten both the foreground and background, unless you are intentional about preventing this. Look for a background that is unobtrusive, especially if you have people in the picture. Be sure a branch isn’t sticking out from behind someone’s head. If you are photographing flowers, make sure there aren’t limbs or weeds distracting from the flower. Always be sure to consciously check your background before clicking the photo. Another trick is to blur the background by either changing the depth of field or using portrait mode on your camera. Blurring the background isolates the main subject and allows it to fully encapsulate the frame. When photographing wildlife, it is tempting to zoom in as close as you can and only frame the animal. But, oftentimes, if you look carefully at the background, you can use the animal to tell a bigger story. By utilizing these five techniques, you will be able to create photographs that capture the essence of Rocky Mountain National Park. We often forget that the word photography inherently puts you, the photographer, as the author and creator of an image. The Greek root words, “photo” meaning light and “graph” meaning to write, give us the very definition of the word, photography. Photography means “to write with light.” The next time you lace up your hiking boots and sling your backpack over your shoulder, remember that an adventure awaits where you can write with light and make photographs that will last a lifetime. By Murray Selleck There’s not much you can do when you’re inside a thunderstorm cloud with lightning flashing and thunder pounding simultaneously. The crack and flash of lightning hurt our eyes so harshly that even with them closed the light penetrated through eyelids squeezed closed tight. Being inside the belly of a timpani drum while the drummer pounds out a rhythm might give you an idea of the ear punishing thunder but it wouldn’t describe the anxiety of being caught out and exposed in such a mountain storm. That was our luck camped way above timberline on a snowfield up in the North Cascades. We were a group of climbers on a month’s long mountaineering course with the National Outdoor Leadership School and we were just about as exposed as a person could be. The day had been overcast, not unusual for the North Cascades. Across a deep valley from us was Mount Johannesburg with a strange lenticular cloud silently smothering its summit. The sun was setting and an eerie orange, green and yellowish glow was coloring the clouds. It was such an unusual color it created a feeling of unease in all of us. And what felt like a heartbeat, the cloud shifted and moved onto us and let loose its maelstrom. We did what we could taking all our ice axes and planting them in a cluster above camp to create a lightning rod. Or so we hoped. We grabbed a couple tents and raced down the snowy slope loosing as much elevation as possible before rain, thunder, and lightning told us far enough. We crammed as many of us that would fit into a few two person tents and waited it out, each of us silent with our own thoughts of adrenalin enhanced doom. Never again is the take away lesson of that experience. One hopes to never again be so susceptible to good or bad luck or whims of a mythological Zeus. But for those of us who love the mountains, love being among the highest peaks, we take precautions, plan, pack, minimize the risks as much as possible and return again and again. There are about 25 million lightning strikes pre year in the United States according to the Lightning Safety Council. Each one has the potential to cause damage or even kill. Colorado ranks 19th in the USA among the 50 states in the number of lightning strikes. On average we receive about 500,000 lightning flashes a year. Lightning can travel up towards 25 miles away from a storm cloud. “Out of the blue” is not unrealistic when it comes to lightning. There’s a saying “when thunder roars go indoors.” What is the best thing to do when even when despite your best planning has you caught out in nasty storm? Hunker down by making yourself as small as possible? Get cozy under a tree? Group up and call for Mr. Wizard to come save the day? Here are some basic lightning precautions do’s and don’ts while on a day hike or backpacking.