|

Notes from the

Trail |

|

By Dawn Wilson, Dawn Wilson Photography In August 2020, the Cameron Peak Fire started north of Rocky Mountain National Park. On the sunny summer day of August 13, 2020, the fire broke out near Chambers Lake in Roosevelt National Forest. The conditions were ripe for a wildfire to quickly spread, with low humidity, high winds and large amounts of dry forest fuel in the area. By the end of August, the fire was 23,022 acres, only 5% contained and burning east. Residents of Estes Park and Glen Haven became concerned that the fire, which was burning timber in the area of Poudre Canyon west of Fort Collins but only a few miles north of Estes Park, may spread south into the valley. By early October, the Cameron Peak Fire engulfed thousands of acres of forest and became Colorado’s largest wildfire on October 14. On October 18, the fire was the first in Colorado’s history to surpass 200,000 acres in size. As close as the Cameron Peak Fire was to Estes Park, with flames and large plumes of dark gray smoke visible to the north of Lumpy Ridge, it was the East Troublesome Fire that caused the evacuation of the entire town, the first in the history of Estes Park. The East Troublesome Fire seemed like a distant tragedy when it started on October 14, 2020, near Kremmling, Colo., more than 40 miles away as the crow flies. Within 36 hours, however, from October 21 to 22, the East Troublesome Fire grew more than 120,000 acres when a perfect storm of conditions developed for rapid fire growth. Starting at approximately 19,000 acres on the morning of October 21, the fire consumed a total of 125,678 acres by the end of that day. By the end of the following day, that number had exploded to 189,505 acres. Unseasonably warm temperatures, humidity levels that dropped to about 11% and wind gusts of 60 miles per hour caused the fire to roar through the dry timber in the Arapaho National Forest. The fire that had been manageable but steadily growing up to that afternoon, turned into an inferno that burned 18 miles through Grand Lake, the west side of Rocky Mountain National Park and, in an unusual event for wildfires, a spot fire jumped over the Continental Divide in just one evening. Estimates put the fire advancement that night at 6,000 acres per hour. Where the spot fire landed in Rocky Mountain National Park during that advancement set up a direct run towards Estes Park. A rapid evacuation order was put in place for the entire town of Estes Park. U.S. Highway 34 had already been closed due to the extreme fire behavior of the Cameron Peak Fire still burning to the north but was reopened to allow residents to seek shelter in Loveland. Many used U.S. Highway 36 to reach Lyons, Longmont and Boulder. Others headed south towards Black Hawk. All residents of Estes Park were now in a dash to get out of town. It would be a week before they were allowed to return. The dramatic weather event that caused the rapid growth from October 21 to 22 transitioned into another dramatic weather event when a winter storm moved into the area late on October 22 and into October 23. Several inches of snow dropped during that latter weather event causing an almost immediate stop in the growth of the East Troublesome Fire, which only grew about 5,000 acres over the next three days. Much of that fire advancement was within Rocky Mountain National Park near Estes Park. By the time these two fires were 100% contained in late 2020, they had burned a combined 402,725 acres – 193,812 acres in the East Troublesome Fire, which was 100% contained on November 30, and 208,913 acres in the Cameron Peak Fire, which was 100% contained on December 2. They would become Colorado’s largest fires in the state’s history. That year also marked Colorado’s worst fire season, with more than 665,000 acres burned across the state. When the fires were declared contained, nearly 30,000 acres had burned in Rocky Mountain National Park, including: a large portion of the Kawuneeche Valley, areas near Cascade Creek, Hague Creek and Mummy Pass Creek in the northern region of the park, and the Fern Lake, Spruce Creek, Moraine Park and Upper Beaver Meadows areas on the east side of the park. Two people – Lyle Hileman, 86, and Marylin Hileman, 84 – died in the East Troublesome Fire when they chose not to evacuate, staying instead in the basement of their Grand Lake home. They were the only two human casualties of the two fires. The East Troublesome Fire destroyed 555 structures, including 366 residences; many were in Grand Lake. The Cameron Peak Fire burned 469 structures, which included 224 residential structures. Today, due to the extensive work done by trail crews, much of Rocky Mountain National Park has reopened after the 2020 fires. Although the Sun Valley Trail in Kawuneeche Valley has reopened, the area west of the trail remains closed. The Upper Mummy Pass Trail in the northern portion of the park also remains closed. All other areas have reopened but the damage is still quite visible with burn scars, fallen trees and cracked rocks throughout the burn areas. For as damaging as the fires may have been for the park and the surrounding areas, regrowth is visible. The first summer after the fires produced an abundance of wildflowers throughout the region, especially large patches of fireweed, a flower named for its rapid growth in areas after wildfires. The following year large patches of lupine grew in the burn scars. Small lodgepole pine trees can also be seen growing in Kawuneeche Valley where the fire helped to open up their cones. Although it takes about 100 to 200 years for lodgepole pine trees to reach maturity, these little one-foot-tall trees are a sign of nature’s resilience in the face of adversity. Along the Fern Lake Trail, abundant aspen groves and patches of chokecherries fill the landscape.

The park lost several historic buildings in the fires, including the Fern Lake Backcountry Patrol Cabin. Built in 1925, it was the park’s oldest structure. Also lost in the East Troublesome Fire were the historic Onahu Lodge, the Green Mountain cabins, the Grand Lake entrance station, the Trails and Tack Barn (and its contents) and the four-bay garage at the Trail River Ranch. Plans have been approved to replace the Green Mountain cabins, which were used for employee housing, with a new housing complex near the existing park housing area on the west side of the park. A vault toilet at Harbison Meadows that burned in the East Troublesome Fire has already been replaced and construction continues on the Grand Lake entrance station. Experts in wildfires and climate change agree that large and rapidly growing wildfires are unfortunately here to stay. If you own property in Estes Valley, contact the Estes Valley Fire Protection District for a free wildfire property assessment. Application information is available at: https://www.estesvalleyfire.org/wildfire-property-assessments.

0 Comments

By Dawn Wilson, Dawn Wilson Photography Did you know that headdresses have come back in fashion? Headdress you say? What the heck is a headdress? Is that like a ring of flowers or a bonnet of feathers? Well, kind of. Headdresses catch the lady’s eye – but only cow elk truly find these “top hats” made of branches, twigs, grasses, leaves and anything else a bull elk can snag into his antlers something to take notice of in the fall. We have entered the mating season – or rut – for the Rocky Mountain elk and the headdress plays a part in the annual courtship process of the elk. Timing of the elk rut This magical season starts each year about the second week of August when the bull elk shed the velvet from their antlers. Although the elk have not quite entered the rut season, this transformation is the first sign of the impending cacophony of bugles, glunks, barks and chuckles that will fill the mountain valleys in a few weeks. As testosterone in bulls increases, it sends a signal to the vascularized velvet to stop providing nutrients to the growing antlers. As the blood flow stops in this outer layer of fuzzy skin over the antlers, the velvet dries up and peels away. It is believed to be itchy to the animal, causing him to scrape and rub it off his rack. The process only takes about 24 hours once started, leaving behind the underlying bone stained red from the blood in the fallen velvet for a few days. His antlers now need to be prepped for battle. For the Rocky Mountain elk, their antlers are the largest of the six subspecies of elk, weighing up to 40 pounds on the largest and healthiest bulls. These projections extending from a pedicle on his head will be used to show his size, maturity, health and fighting ability during the tournament to breed. The bull will sharpen up the points and smooth out the sides by rubbing the antlers on trees, branches, shrubs and even the ground. As August blends into September, the rut season begins to come into full swing. Although warm, sunny days can keep the elk herds hidden in the shade during the heat of the day, a cool, cloudy day is sure to offer a longer opportunity to observe the massive animals. The rut season in Colorado peaks from about the third week of September to the first week of October. As cows become impregnated and testosterone levels begin to decline in bulls, the activity begins to wind down by the middle of October. By early November, many of the bulls are gathering back into bachelor herds and resting out of sight to recuperate from the taxing activities of the season. By late fall, the piercing bugle becomes a distant memory as the meadows become quiet again and the snow begins to blanket the dried grasses of summer. Many of the larger bulls have been actively pursuing cows, fighting other suitors and chasing away interlopers since late August. The bulls, which can weigh as much as 700 pounds, may lose up to 20% of their body weight during this time. Some bulls often tap out of the activity early, either due to injury or exhaustion, giving younger bulls a chance to spread their genes. Catching a glimpse of the action The best times of day to watch the mating activity is in the early morning and late afternoon when the air is still cool and the dampness may hang heavy in the meadows. Morning in particular can offer the best chance to experience foggy meadows, dew covered vegetation or fresh snow across the scene, all ideal for unique photographs. In Rocky Mountain National Park, the best places to observe the rut activity are open meadows, such as Horseshoe Park, Upper Beaver Meadows and Moraine Park, with the latter being one of the most productive locations for just the sheer volume of animals in the vicinity. Some smaller groups of elk will remain on the tundra near Trail Ridge Road until the first snowfall. A large herd of elk also live in Kawuneeche Valley on the west side of the park. Many of these elk, however, venture outside of the park into Arapaho National Forest where hunting is permitted. As a result, these elk tend to show more typical elk behavior of being active from dusk to dawn. Outside of Rocky also offers ample opportunities to watch a unique mix of rutting adult elk while the confused calves experience their first rut season. In Estes Park, it is not unusual to see elk walking downtown, strolling through Bond Park, rubbing their antlers on trees near the Visitor Center or cooling off in Lake Estes. Elk can be found just about anywhere in town during the rut season, including either of the golf courses, Stanley Park, the YMCA of the Rockies or even The Stanley Hotel property. For this reason, it is important to keep a watchful eye when in town as a startled elk coming around a corner may not let you pass. Leader of the pack Some believe that the dominant bull determines the path of the herd during the rut season. Although it may seem like he is corralling his harem – a group of elk made up of cows, yearlings and calves – it is actually the lead cow that determines when and where the unit of animals moves. The bull, however, will attempt to maintain his personal group by posturing, patrolling and bugling – both to keep the attention of the cows and to warn the competition. The dominant bull often follows behind the group as well almost like a security patrol. If a cow wanders away from the group, the bull will cut off her escape and push her back to the larger group. This whole process will continue throughout the rut season. Methods for attracting cows During the rut, the bull will also make gestures to attract females – and that’s where the headdress comes into play. One way bulls will show their dominance and mark their territory is to urinate in a shallow wallow. They may then paw at it with their hooves and thrash about the scented mud with their antlers. Sometimes the antlers will come up with that stunning headdress – the bigger the better is what he hopes will win the attention of a cow. Bulls will also urinate on their bellies, legs and feet, a kind of wapiti cologne. As the rut season progresses, visitors to the meadows in Rocky Mountain National Park may start to notice a scent reminiscent of a horse farm. This is the musky odor of the urine left by the bulls. One other behavior wildlife watchers may observe during the rut is a funny expression made by the bull elk after sniffing the urine-soaked area created by a cow.

In the urine are pheromones, the chemical smell of being in estrus. After a cow pees, a pursuing bull may sniff that area to see if she is ready to mate. To really fill those nostrils with the smell, he will lift his head and curl his upper lip into what looks like a snarl. This behavior is called the flehmen response. Doing the odd maneuver helps the pheromones reach the vomeronasal organ, a highly sensitive organ in the nasal cavity that can detect specific chemical scents. In this case, it helps the bull determine if the cow is in heat. And then everything settles back down in the meadows, the bulls return to being friends again as they gather back into their bachelor herds, and the various harems will join into one massive herd. That large herd, which can be several hundred strong, will move down into the foothills in mid-to late November. These elk will spend the winter at lower elevations. This annual ritual of fall is a sight to behold for anyone interested in the intricacies of wildlife behavior. In Rocky Mountain National Park, a timed entry reservation system is in place through much of the rut season. For the Bear Lake Corridor, which includes Moraine Park, a timed entry reservation is required from 5 a.m. to 6 p.m. through October 19. The rest of the park, which includes Horseshoe Park, Endovalley, Upper Beaver Meadows, Trail Ridge Road and Kawuneeche Valley, requires a timed entry reservation from 9 a.m. to 2 p.m. through October 13. Please remember to watch wildlife respectfully and be courteous to others also enjoying this enchanted season of valley-filling sounds, sparring bulls and courtship like no other animal in Colorado. by Jamie Palmesano, Brownfield’s The science and the health benefits of time in Rocky Mountain National Park (all photos by Jamie Palmesano) September in Rocky Mountain National Park (RMNP) is a living symphony: gold aspen leaves shimmering, cool alpine air, and the unforgettable bugle of elk echoing across the valley. It’s beautiful and profoundly good for you. A growing body of research shows that time in nature measurably calms the stress system, sharpens attention, improves mood, and even correlates with longer, healthier lives. Here’s a quick tour through the science, practical “doses,” and exactly how to experience it in Rocky Mountain National Park this fall. The Science of Why Nature Heals Two hours a week is a meaningful goal. According to a large study of nearly 20,000 people from Monitor of Engagement with the Natural Environment Survey, those who spent more than 120 minutes in nature per week were significantly more likely to report good health and high well-being than those who didn’t regardless of whether that time came in one long visit or several short ones. The benefits plateaued around 200–300 minutes. Stress chemistry shifts in minutes. In a real-world “nature pill” experiment, 20–30 minutes outdoors produced a 21% per hour drop in cortisol, our primary stress hormone (salivary alpha-amylase fell even faster). This means even short time outdoors meaningfully quiets the body’s stress response. Risk goes down across the board. According to a paper “The Health Benefits of the Great Outdoors” from the National Library of Medicine, a meta-analysis pooling over 140 studies linked greater greenspace exposure with lower cortisol, heart rate, and diastolic blood pressure, plus reduced type II diabetes (OR≈0.72), cardiovascular mortality (OR≈0.84), all-cause mortality (OR≈0.69), and preterm birth (OR≈0.87)—associations that point to broad, whole-person benefits. Your brain gets a reset. A controlled experiment showed a 90-minute nature walk decreased both rumination (repetitive negative thinking) and activity in the subgenual prefrontal cortex, a brain region tied to depression risk. Interestingly, these effects were not observed after an urban walk, but were seen after being in the great outdoors. Listening matters, too. Natural soundscapes—wind in the pines, bird song, and water are more than ambiance. A synthesis of studies found exposure to natural sounds improved health and mood outcomes and reduced stress, underscoring why quiet, wild places feel restorative. In this paper, the authors explored whether and to what degree natural sounds influence health outcomes using a systematic literature review and meta-analysis, and found that natural sounds provide important ecosystem services, and parks can bolster public health by highlighting and conserving natural soundscapes. Why Rocky Mountain National Park is a “Healing Lab” 355 miles of trails; every elevation, every pace. RMNP spans serene lakeside walks to sky-high tundra hikes, with elevations from about 7,500 to over 14,000 feet. There is something for everyone from flat, handicap accessible trails around a number of gorgeous lakes to boulder laden fields requiring rock scrambling and intense climbing. No matter your age or fitness level, RMNP has something special waiting just for you. Trail Ridge Road crests at 12,183 feet, almost carrying you into the sky where trees give way to tundra and horizon-wide views take your breath away. These classic “awe triggers” that can shrink stress by shifting perspective and giving you a sense of how big and beautiful this world really is. There’s Something Special about September. September in the Rocky Mountains has a soundtrack all its own. The elk rut typically peaks mid-September to mid-October; evenings in Moraine Park, Horseshoe Park, and the Kawuneeche Valley can be unforgettable. The bugle of the elk echo through canyon walls and the Estes Valley. The noise is unmistakable and calls you into the wild. The sound of the aspen leaves quaking in the wind against the sapphire sky is concert itself. If you have never visited Estes Park in September, add it to your bucket list. Our favorite fall hikes include Alberta Falls, Bierstadt Lake, Cub Lake, Deer Mountain, and Lily Lake. Plan for timed entry. From late May through mid-October, RMNP utilizes a timed entry system. The Bear Lake Road Corridor requires the “Timed Entry + Bear Lake Road” reservation during peak hours, which you can reserve at Recreation.gov. If you would like to go to Moraine Park between 5am and 6pm, you will need a timed entry pass, which can be obtained on the first day of the previous month or at 7pm the night before. However, there are numerous destinations that are accessible without a timed entry permit before 9am and after 2pm. A Field Guide to Science-Backed “Doses” of Nature

1) The 20-Minute Reset (any day you can get there)

Creation is generous offering rest without requirements and welcome without walls. Here, stillness is a sanctuary and the wind through pines becomes a gentle benediction. There’s a call to meet the Maker on the trail and in creation’s cathedral, our souls can be restored. by Scott Rashid Colorado Avian Research and Rehabilitation Institute All Photos by Scott Rashid Few people are aware that there are six species of owls that inhabit the Estes Valley and Rocky Mountain National Park (RMNP). They range in size from the diminutive Flammulated and Northern Pygmy-Owls reaching a maximum length of about seven-and-a-half inches and weighing about two ounces, to the 24-inch, four-pound Great Horned Owls. The other owls found here are the Northern Saw-whet Owls, Boreal Owls, and the Long-eared Owls. All but the Flammulated Owls feed upon animals and birds. The Great Horned and Long-eared Owls use nests constructed by other birds such as Red-tailed Hawks, Cooper’s Hawks and even American Crows and Black-billed Magpies. The Great Horned Owls are the earliest nesting owl and most often seen owl in the area. These birds frequently begin their courtship in January, if not before, and begin nesting in March. The female lays between one and four eggs two to three days apart. But has been known to lay eggs more than a week apart. She begins incubating with the first egg. Incubation lasts about 35 days and is done exclusively by the female. Her owlets remain on the nest for about a month before they begin exploring their surroundings. Long-eared Owls are one of the more difficult birds to find nesting, as they are experts at remaining still and their cryptic coloration blends perfectly with their surroundings. Both male Great Horned and Long-eared hoot to attract females. These birds can be heard in the spring after dark. The Boreal Owl nests specifically in the high spruce-fir forests above 9000 feet. In that habitat they are the top avian predator. They are also the largest of the cavity nesting owls in valley and RMNP. Many of these owls remain on their territories year-round and feed upon the voles and birds in the area. Due to their larger size and strength, they can pre upon animals as large as red squirrels, small hares, birds large as Canada Jays, and Pine Grosbeaks. Due to their large size, they need to nest in a cavity constructed by a Northern flicker or a larger natural cavity. Once a female is attracted by the male, and she has accepted the cavity, the male is no longer allowed into the cavity. He spends his time hunting for the incubating female and later for the female and young. The young remain in the nest for about a month and frequently fledge in May or June. The Northern Saw-whet, Flammulated and Northern Pygmy-Owls all prefer the same habitat, as they have been found nesting in the same tree in different years. Their preferred habitat is a combination of Douglas fir, aspen, ponderosa, junipers, downed logs, openings in the forest and a water source. As for nesting, the Northern Saw-whet Owl begins nesting in March, the Northern Pygmy-Owls begin nesting in late April, early May and the Flammulated Owls begin nesting in May and June. All these owls have about a 30-day incubation period and their chicks remain in their nests for about 30 days before they fledge. The Flammulated Owls usually raise two owlets, the Northern Pygmy-Owls raise between two and five owlets and the Northern Saw-whet Owls if in a natural cavity have two owlets, but if they are using one of our nest boxes, they can raise as many as five or six owlets. This is because the nest boxes are much larger than a natural cavity, enabling more owlets to fit in the box and survive.

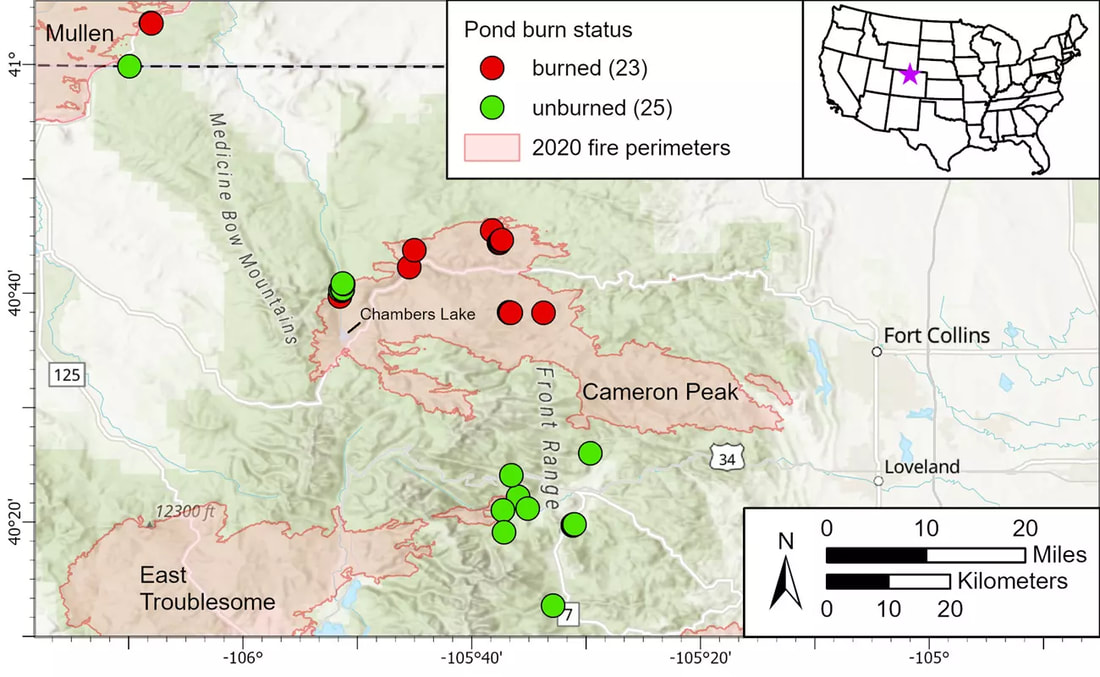

With the exception of the Flammulated Owls, the other species prefer to nest near water, as they often get dirty when capturing prey and need to bathe to clean their feathers. Being insectivores, the Flammulated Owls migrate to Mexico in the fall, remaining there until spring and returning in late April to mid-May. Flammulated Owls prefer moths, larvae and caterpillars. by Scott Rashid Colorado Avian Research and Rehabilitation Institute Colorado Avian Research and Rehabilitation Institute As fall ends and winter begins, birds begin to move to their wintering grounds, or the areas where they will spend the winter months, where they hope food and water is plentiful. Some of the birds that nest here also winter here, but other birds simply arrive in September and October to winter here, here being Colorado and specifically the Estes Valley and Rock Mountain National Park (RMNP). Migration takes many forms, and in fact, there are multiple types of migrations. There is elevational migration, latitudinal migration. longitudinal migration, circular migration and leapfrog migration. Different species use these varying types of migration. For example, shorebirds move north through the center of the country, migrate in a more circular form. From their wintering grounds along both coasts, they simply move north through the center of the country as they can feed in the flooded fields during their spring migration. Yet when they migrate in the fall, the center of the country if filled with crops, leading them to migrate south via either east of west coast to winter along the coasts of the Atlantic, Pacific and the Gulf of Mexico, migrating in two large circles. Birds here in the west have an elevational migration. Birds including Clark’s Nutcrackers, Horned Larks, and American Pipits nest either on or close to the Alpine Tundra and winter in Estes Park or along the grasslands of Eastern Colorado. Another example of migration is leapfrog migration. American Crows in the west have this type of movement. For instance, birds here in Estes Park head southeast in the fall/winter and are replaced by northern birds from British Columbia and Alberta, Canada. The species that both nest here and spend the winter in the Estes Valley include the corvids; Common Ravens, American Crows, Black-billed Magpies, the jays, and the Clark’s nutcrackers. The three species of nuthatches stay here as do some of the Brown Creepers. Townsend’s Solitaires and American Robins remain here as do Chickadees. Mallards, Common Goldeneye and Common Mergansers remain as do the Canada Geese. Some of the birds of prey winter here as well. These include the Red-tailed Hawks, Bald Eagles, Cooper’s Hawks, Sharp-shinned Hawks, Northern Goshawks, Great Horned Owls, Northern Pygmy-Owls, Boreal Owls, and Northern Saw-whet Owls. Birds that migrate out of Estes Park and include, most if not all the warblers, hummingbirds, and flycatchers, Pine Siskins, Hermit and Swainson’s Thrushes, Ruby-crowned Kinglets, Blue-winged Teal and Flammulated Owls. The birds that will appear in the fall/winter to spend the colder months in Estes Park and other parts of Colorado include the three species of rosy-finches, Evening Grosbeaks, Snow Buntings, Northern Shrikes, Lapland Longspurs, Pine Grosbeaks, Dark-eyed Juncos, and Rough-legged Hawks. It is a good idea to begin putting out bird seed for the winter birds in mid-October before they begin arriving. Once they are here they will need food to either refuel to continue moving or enough food to keep them here for the winter. As for what type of seed to put out, sunflower seed is always a good bet, as is millet and suet. Keep your eyes peeled for any of these species. Look for Black, Gray-crowned and Brown-capped Rosy-finches, Oregon, Slate, and White-winged Juncos, Snow Buntings, Evening Grosbeaks, and White-winged Crossbills. by Marlene Borneman In the autumn months, Colorado is known for spectacular displays of golden quaking aspens (Populus tremuloides). Mountainsides glow in deep golds, red and oranges mid-September through mid-October. No doubt an aspen grove or even one lone aspen tree in the autumn months can take your breath away. In Rocky Mountain National Park many native shrubs and flowering plants give brilliant fall colors on the forest floor, on hillsides, and along streams and creeks. Here is a tour of Rocky’s Best autumn colors beyond the aspens to take in while hiking this fall. Willows - Rocky Mountain National Park boasts many species of willows. Willows, (Salix), grow along creeks, streams, and rivers, in all elevations giving stunning deep yellows. Squashberry - Viburnum edule, also known as highbush cranberry, decorates moist areas along streams and creeks with crimson red leaves and red berries making for a very pretty fall display. The berries contain a drupe which is a stony pit. Chokecherry - Prunus virginiana, is in the Rose Family Chokecherry. It's a large shrub with white fragrant flowers flowers in the spring and dark purple berries in late summer. In autumn months chokecherry shrubs gives deep red, orange and yellow colors to the hillsides. Ferns hugging the forest floor show off hues of deep bronze, shades of brown and gold. Whortleberry - Vaccinium myrtillus, carpets the forest floor with amazing colors that hang on until late October or until the first snowfalls. Golden hues of grasses in the high meadows shimmer in the sunlight. Alpine avens give the tundra a striking scene with their fern-like leaves turning the tundra into a blaze of deep maroon. Fireweed - Chamerion angustifolium, with deep pink flowers in late summer transforms in fall with showy seed capsules wrapped in long hairy magical strands and spirals appearing magical along their large deep red foliage. The most common species of Geranium, Geranium caespitosum, adds to the understory with shades of red, yellow and orange leaves. Oregon-Grape - Berberis repens, spreads in large masses in the understory of the forest. Oregon-grape produces large, deep blue, and purple berries with royal- red thick shiny leaves adding a striking scene to a hike. By Scott Rashid Colorado Avian research and Rehabilitation Institute (CARRI). Since 2007 the Colorado Avian Research and Rehabilitation Institute has been studying the fall movements of both Boreal and Northern Saw-whet Owls in Northern Colorado. This is accomplished by capturing birds in the fall. After they are captured, we check their condition by measuring and weighing them, then a numbered leg band is placed on each owl to identify individuals, before releasing them. Birds are captured in 3, 40-foot (12 meter) nets. Each net has four pockets that stretch the length of the net. The nets are placed in the woods in a “U” shape. After dark, the call of the owl we are intending to capture is broadcasted. As the owls are moving to what will eventually be their wintering grounds, in the fall, they come towards the call, fly around the speakers and land in one of the nets and are captured. To reduce excess stress to the owls, we place video cameras on each of the nets so we can monitor the nets in real time. The signal from the cameras is sent via WIFI to a computer that is inside a nearby building allowing us to monitor the nets. This way, as soon as the owls land in one of the nets we can rush to the nets and extract them, place them in a cloth bag and bring them into the building to be processed. Processing the owls consists of determining the age and sex of each bird, placing a numbered leg band on them, measuring their wings and tails, weighing each bird, and determining their age before releasing them. The information that we obtain from the owls is sent to the bird banding laboratory in Laurel Layland via computer. If any one finds a banded bird, they simply contact the banding laboratory using their website www.usgs.gov/labs/bird-banding-laboratory, fill out the information, and the lab will let them know who originally banded the bird and were it was banded. The banding laboratory will then send you a certificate of appreciation. They will also let the person that banded the bird know that the bird was obtained. The calls of the birds are broadcast using a cell phone and Bluetooth speakers. The cameras are powered using a portable power station. The battery lasts about eight hours, enabling us to work well into the night to research the owls. There are multiple banding stations all over the country capturing these owls. We are one of the few in the country that use cameras to monitor the nets. We have found that having cameras on the nets reduces stress on the bird immensely, eliminates predation of the owls when they are in the nets, and enables us to run off any large animals like bears, elk, and deer that come near the nets. These large creatures can destroy the nets by walking through them. As we have been operating our banding station for many years, people from around the country come to see the owls. Some of these individuals are fellow researchers that want to see how our operation compares to theirs. As few banding stations use cameras and want to see how well they work for the project. This season, we have several wonderful volunteers that will be assisting us with the research. Some have never seen this type of research before, but are excited to learn the process, and a few have assisted us for years and have their assigned jobs. This is an amazing operation to see, as it is a good way to see the owls up close in and learn about their natural history. Since we began capturing owls in the fall, we have banded more than 400 birds. The surprising thing about this is we have only had three owls either recaptured or found dead. One bird banded in Pinewood Springs was recaptured in Estes Park a year later. Another bird captured in Estes Park, was recaptured live and released in Eastern Pennsylvania, and another bird was recaptured in the same banding site that it was originally banded. This research is important to see how many of these owls are in the area and what the health of the birds are, which also tells us of the health of the forests where the bird reside. Beaver Ponds: How do Post-Fire Sediment and Carbon Dynamics Contribute to Watershed Resilience?9/26/2024 This article is republished from Continental Divide Research Learning Center Beavers are an important part of river systems and are often referred to as ecosystem engineers. They construct dams using riverside vegetation that pool water on the upstream portion of the river. The dams also slow the water flow. The combined effect of pooling and slowing water allows sediment to settle upstream of the beaver dam, a process that naturally improves water quality.

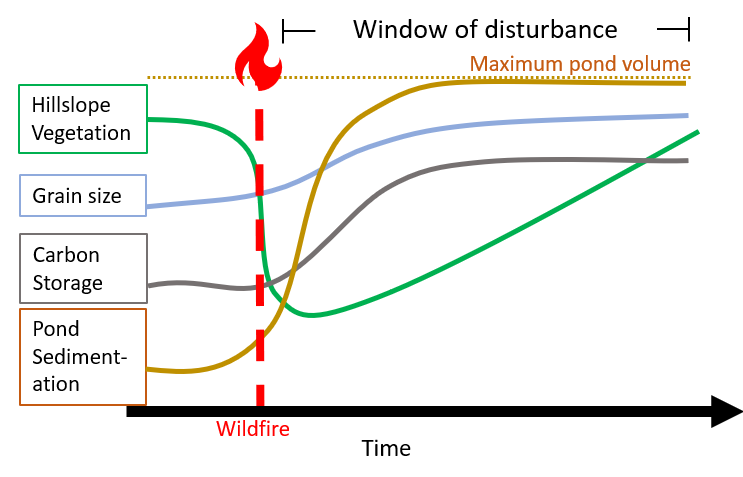

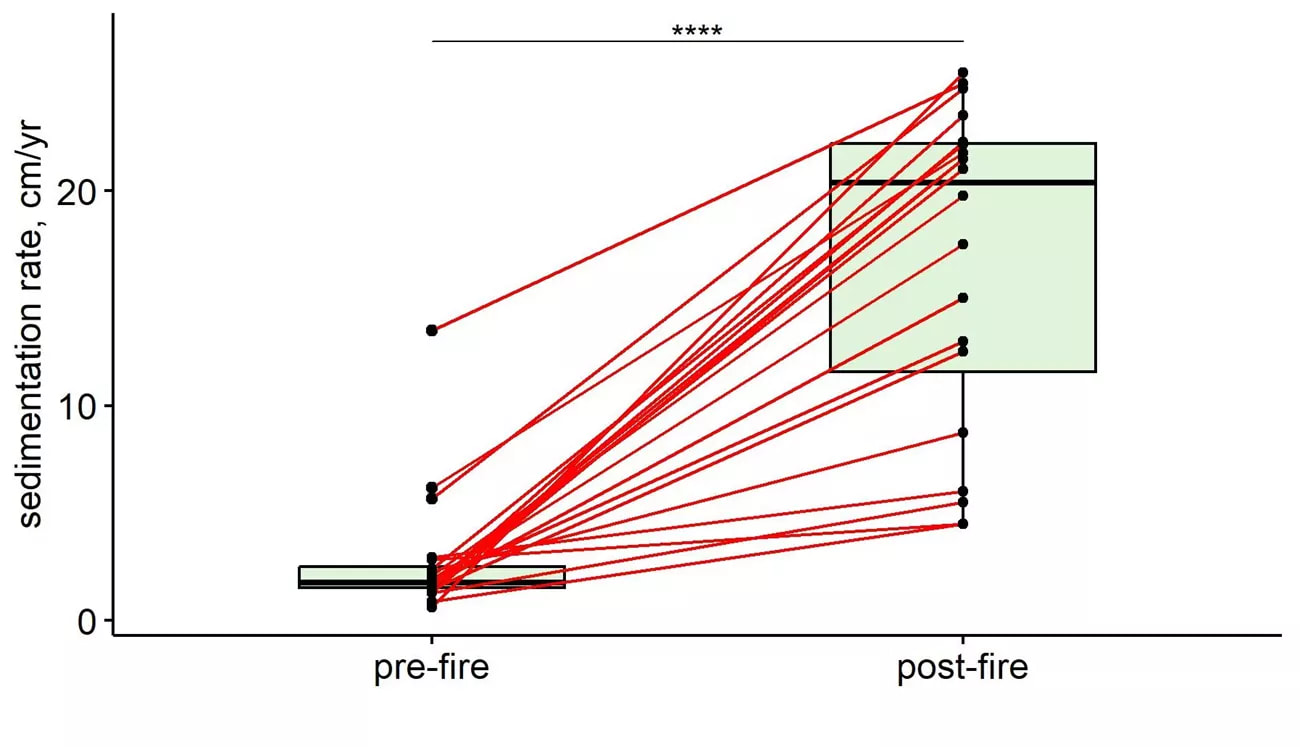

The retention of sediment and carbon by beaver dams can dampen potential impacts to drinking water and aquatic habitat. Immediately following a fire is the time when the most sediment enters rivers and creeks. Knowing that the sediments would travel down towards the river valleys, Sarah Dunn - a graduate student at Colorado State University - decided to study the impacts of the fires on the sediment retention in beaver ponds within and outside of burned areas to understand whether beaver ponds impact the ability of a watershed to recover after disturbance such as fire (Figure 1). The ability of a watershed to recover after a disturbance is known as watershed resilience. Research Study To determine how beaver ponds affect the resilience of watersheds, Dunn set out to perform a research project to answer the following three questions: Do burned ponds store greater relative volumes of sediment compared to unburned ponds?, Do post-fire sedimentation rates in burned ponds exceed pre-fire and unburned sedimentation rates?, and Is post-fire sediment stored in beaver ponds coarser and have a higher abundance of organic carbon relative to pre-fire sediment? The rate and volume of sediment, carbon storage, and sediment grain size are expected to increase after a fire during the period when vegetation is recovering (Figure 2). Dunn used field, laboratory, and geospatial methods to answer these questions. During the field component of the project, 48 beaver ponds were surveyed. Ponds were located in both burned and unburned areas. In the field, surveys were conducted of the pond perimeters and sediment and water depths within the ponds. Dunn also collected sediment cores to identify charcoal within the layers of sediment that had been deposited. Laboratory analysis included measuring of total organic carbon and grain size of the pond sediment. Lastly, geospatial analysis was performed on the field and laboratory data. Results For the beaver ponds that were sampled and analyzed for this research project, about half were located within a burned area and the other half located in an unburned area. The average sediment volume stored in the ponds was 796 m3 and sediment volumes ranged from 4 m3 (about half a dump truck load) to 7,888 m3 (about 500 dump trucks worth). Sarah determined that burned area beaver ponds stored higher relative volumes of sediment. The sedimentation rates after fires were significantly different from sedimentation rates before the fire (Figure 3). In fact, the sedimentation rates in ponds post-fire were an order of magnitude higher than pre-fire rates in ponds. In analyzing the grain size of sediments in burned and unburned beaver ponds, Sarah found that the grain size and amount of organic carbon did not differ significantly. Applications in the NPS Beaver ponds, which once were abundant on the RMNP landscape and are now less common, drastically changing the hydrology of the environment. Beaver dams (Figure 4) create upstream ponds that store sediment and carbon. Due to the effects, mimicking beaver dams with structures is a strategy under consideration for fire-prone areas. The research that Sarah conducted provides evidence that beaver ponds effectively trap and retain post-fire sediment. The increased sediment in beaver ponds post-fire builds on the existing knowledge that beaver ponds provide to the ecosystem is evident through the increase of pooling water and decreased water flow (Figure 4). These findings contribute to the park’s efforts to restore beaver habitat.

by Ally Anderson Physiology and Medical Sciences UA Franke Honors College University of Arizona “The mountains are calling and I must go." This is a popular quote by John Muir that rang true for a young college student named Ely Bordt. His first experience traveling to the Rocky Mountains pulled him in and never let him go. The Rockies challenged him and changed him, teaching him what his mind and body are truly capable of with enough grit and enthusiasm. It all started the summer of 2017 when Ely participated in a Colorado Ecosystem Field Studies program. The field study website describes this experience as ”An opportunity to study the Colorado Rockies and apply your classroom and textbook learning while immersed in an incredible mountain ecosystem setting.” After that first taste of living and working in the mountains, Ely's life trajectory shifted as he felt a strong pull towards the mountains postgrad. As a wide-eyed college graduate, Ely jumped at the opportunity to trade the flat lands of Indiana for the Colorado Rockies. Flashforward to February of 2021, Ely got a job in Longmont, Colorado and made a point to be on a trail whenever he wasn't working. Having no prior experience hiking or climbing, Ely would often hit the trials with the sole motivation of good views and impressive photos. This all changed when a year later he met his mentor, Kevin Rusk, a seasoned mountain climber with a big heart to show Ely the joy of pushing his body to new heights in the Rockies. Kevin taught Ely how to use his gear to climb in different terrains and instilled in him the importance of precautionary measures like bringing a rope even if you don't think you’ll need it. Ely followed Kevin's footsteps all winter, learning to climb glaciers, starting at their first climb together up Tyndall Glacier. When that winter was over, they climbed rocks together through the summer. “(Kevin) thought, let's get you off a trail and into some ropes, and since then... It erupted and now I'm snow climbing, rock climbing, and scrambling and don't so much stick with trails anymore, I aim to get off the trails.” -Ely As mileage started to increase and he started to fall more and more in love with the mountains, Ely went from a novice climber to someone whose mind revolved around getting back into the challenging terrain of the mountains. Rocky Mountain National Park and the Indian Peaks south of the park became his favorite spots in his early years of serious climbing. He worked tirelessly to condition his body to handle even the most advanced terrain alongside his mentor Kevin. How is it that in only a few short years, Ely has managed to completely shift his lifestyle from somewhat sedentary to extremely athletic? What are the physiological implications that come along with the ability to sustain endurance and strength while clinging to the side of a mountain? How does Ely fuel and train his body to perform at such a capacity? Shift in Lifestyle and Mental Headspace Ely has not always been able to casually climb Longs Peak. Longs is a challenging 14er that requires great deals of mental and physical toughness and is a great achievement for those who complete it. Ely has joyfully completed this climb multiple times and has plans to climb it again! This kind of ambition and ability to take on such challenges illustrates the dramatic shift from how he held himself in his childhood. He explains his early years as a period of time when he was overweight and lacking motivation to keep a consistent exercise regime due to a lack of excitement towards most types of physical activity. ”Prior to hiking, I was a gamer. I spent a lot of time online. There's a lot of toxicity online. I didn’t get out much. Hiking allows me to clear my mind.” - Ely He was an uninspired kid, most often seen indoors playing video games, lacking the desire for exploration or challenging physical feats. Fast forward to the present day, Ely is calmer and more mellow, feeding off of the serine mountain landscape he surrounds himself with. He's a social young adult, full of ambition and he credits this dramatic shift into a more positive headspace to the mountains. “I was entirely unathletic prior to that (moving to Colorado), it was a big change. The views drive me to get out but more so, if I go too long without the mountains, I'm thinking, I need to get a workout in. I need to get active.” -Ely “The mountains are something I get hungry for if I go too long without” -Ely Ely explained how he's tried weightlifting and cycling, but the mountains are the first and only thing that he's seen dramatically motivate him to get active. He has gone from an unmotivated child to a driven athlete looking forward to the next adventure, overall more enthusiastic and motivated about life as a whole. Why Does Exercise Improve My Headspace? As Ely experienced firsthand, there is a link between a lifestyle that prioritizes physical activity and improved mental headspace. The moment someone participates in physical activity, there are neurochemical changes that start taking place. There are hormones directly correlated to stress, which are reduced upon an exercise induced increase in heart rate. As these stress hormones are reduced, chemicals in the brain called endorphins are increased. Endorphins act on the body to brighten a person’s mood and alleviate stress. These chemical changes happen every time a person is physically active and even more consistently in someone who has a habit of increasing their heart rate through exercise. This explains why Ely’s attitude and outlook seemed to transform completely as he became more active. He began to alter his brain chemistry as a whole! Building Cardiovascular Stamina On top of building mental endurance, Ely has also been on a journey of building cardiovascular stamina. This is the ability of the heart and lungs to endure longer and harder through difficult exercise. Coming from an inactive lifestyle in Indiana, Ely describes this as a significant challenge. He started training on lower elevation trails in the Boulder Colorado area and built up to the challenging elevations of the Rocky Mountain National Park. Ely noticed improvements in his cardiovascular capacity when he got out into the mountains as much as possible getting as high as possible! He would celebrate each landmark climb at a higher elevation, constantly pushing himself to get higher and on more challenging trials. Training at Altitude A very common strategy among athletes is training at higher altitudes to develop stronger cardiovascular endurance because of the cardiovascular challenge of being in low-oxygen environments. Something special happens to the body’s ability to carry oxygen when someone puts themselves in a high-altitude environment where the oxygen is thin and less abundant. The low amounts of oxygen trigger a hormone called EPO (erythropoietin), which stimulates the production of red blood cells. The red blood cells begin to grow larger and increase in number to maximize the amount of oxygen they can hold and transport throughout the body. Ely, being an elite athlete who spends the majority of his time exercising at high elevation, has red blood cells that look differently than those of an athlete at sea level who has an abundance of oxygen in the air around them! If Ely were to go down to sea level, theoretically, he would find that his cardiovascular endurance would be even better. He has such a high number of red blood cells at a greater volume ready to make the most of little amounts of oxygen but finding that at sea level there is more oxygen to use than normal. It is very common for athletes to train at high altitudes to change their red blood cell composition and come back down to sea level with an advantage. Fueling the Body to Endure the Mountains Once Ely became more acclimated to the high elevation of the Colorado Rockies he was able to withstand more difficult trails mentally and cardiovascularly. He started to push the limits of what his body was able to achieve and to do so, he needed the right fuel. This meant taking nutrition to a whole new level. Ely describes his diet as high protein and high carb to have energy to perform at challenging levels, restore muscle, and maintain strength. Ely has a specific diet the day before a big hike. He prioritizes water, drinking four liters throughout the day before his planned day in the mountains. He also prioritizes eating as many calories as he can: chips, queso, whole pizzas, you name it. Ely expressed that the biggest component of waking up with energy is drinking substantial amounts of water the day before. While he’s out on the trail, Ely focuses on his sugar intake: fruit snacks, Honey Stingers, and salt tablets with and without caffeine. Ely is slightly anemic, meaning he has a blood disorder that reduces the effectiveness of the blood stream's ability to carry oxygen. To combat this, the morning of a big day in the mountains he will eat two servings of dry Cheerios. This cereal contains 70% of his daily iron intake. Consuming great amounts of iron translates to an increased amount of hemoglobin and an increased amount of oxygen capacity in the mountains. He eats these Cheerios without milk because milk inhibits iron absorption when eaten in conjunction with iron. Importance of Good Nutrition Ely's methods of fueling his body before and during athletic activity are widely used by athletes performing at his level of difficulty. His emphasis on water intake the day before extreme physical exertion is very important, especially on a hot day where perspiration is more likely. Water is important in so many aspects of body functionality including regulation of body temperature, lubrication of the joints, and transportation and digestion of important nutrients. Adequate levels of hydration affect many aspects of athletic performance. Carbohydrates are used by the body as its main fuel source during any kind of energy expenditure. Having a plentiful store of carbohydrates for the body to use will supply more energy and allow it to endure harder and longer. Nutritionists also recommend athletes prioritize snacks throughout the day, as Ely does, to maintain energy and nutrition, keeping the body strong and able to endure. What is Next for Ely Bordt in the Mountains ”My biggest challenge is just bravery” -Ely In past summers, Ely has done a lot of fourth-class scrambling. His goal for this summer is to get into more low fifth-class scrambling. This is the kind of terrain that borders the need for a rope. He aims now to challenge himself on more difficult terrain that is intimidating and more technical. If it is at all possible to be done without a rope, that's the way he wants to get it done. Ely does prioritize his safety, carrying with him what Kevin taught him in the beginning. “When I talk about getting into these technical terrains being my goals next summer, I always go in with what he (Kevin) taught me about having an exit strategy. I'll probably bring a rope and even if I don't use it on the way up, if I get cliffed out and need a way to get out of what I'm on, a rope will always be handy for at least rappelling and getting off.” -Ely Ely wants to get in the right mental space to be able to handle harder terrains such as the north face of Longs Peak. “I can see the goals I had and met, and I'm now wondering what I can do next” -Ely

by Scott Rashid, Colorado Avian Research and Rehabilitation Institute Now that summer is here, birds are singing, nesting and raising their young. In the winter, the common birds include Common Ravens, American Crows, Northern Pygmy-Owl, Black-billed Magpies, Mountain and Black-capped Chickadees, all three rosy-finches, the three species of nuthatches and more. However, when the migrants begin arriving from their wintering grounds the number of bird species exponentially increase. Most of the birds that spend the winter here, also remain here year-round. There are a few species that migrate north to nest. These northern migrants include the Northern Shrike, Gray-crowned Rosy-finch, Common Redpoll, Lapland Longspur, and the Snow Bunting.  Calliope Hummingbird Calliope Hummingbird When summer arrives, birders search out species including Western Tanagers, Black-headed Grosbeaks, Olive-sided Flycatchers, Dusky Grouses, Western Wood pewees, Broad-tailed Hummingbirds, Band-tailed Pigeons, Lesser Goldfinches, and the cliff, barn, violet-green and Tree Swallows. Many of the species that nest here can be seen when you’re hiking. Birds are usually more prevalent at the trailheads than they are in the middle of the trail or the final destination. The trails that seem to have the most species are those that have the most varied habitat. For example, when hiking Upper Beaver Meadows, birds including Olive-sided Flycatchers, Western Wood Pewees, Williamson’s Sapsuckers, Pine Siskins, House Wrens, Warbling Vireos, Green-tailed Towhees, and Chipping Sparrows can be heard and seen with relative ease. Another good birding location is the Alluvial Fan area and the road to the Endo Valley Picnic area. This is a good spot to find Red-napped Sapsuckers, Pine Siskins, Hairy Woodpeckers, Dusky Grouse, Western Wood Pewees, and Wilson’s Snipe. Many of these species can be seen simply by walking along the road and both listening and searching for the birds as they frequently fly over the road. If you venture higher in elevation and hike the area around Bear Lake, and other higher mountain trails, you may find Canada Jays, Pine Grosbeaks, Red-breasted Nuthatches, Black Swifts, Northern Goshawks, Hermit Thrushes, Three-toed Woodpeckers, Hairy Woodpeckers, and Red Crossbills. If you’re on the tundra there are usually fewer species of birds but larger numbers of individual birds. For example, when on the tundra, keep your eyes open for White-tailed Ptarmigan, American Pipits, Horned Larks, Brown-capped Rosy-finches, White-crowned Sparrows, and Common Ravens. All of which are frequently seen with ease. Oddly enough when on the tundra, you may see birds that appear to be out of place. These include Red-tailed Hawks Prairie Falcons, Mountain Bluebirds, American Robins, and even Broad-tailed Hummingbirds. After the fourth of July, very special avian species arrive in the area. These are the Calliope Hummingbirds and the Rufous Hummingbirds. These diminutive dynamos remain here for a few weeks before making their way to their wintering grounds in Mexico. Male Rufous Hummingbird, as their name suggests are rufous colored and stand out at your feeders, as they are brightly colored and aggressive. The Calliope Hummingbirds are the smallest nesting birds in North America. These birds are often less numerous than the other two species, as they seemingly get pushed around by the larger birds when at the feeders. If you’re out and about after dark, listen for Common Poorwills, Common Nighthawks, Northern Saw-whet Owls, Flammulated Owls and Great Horned Owls. When you’re outside this summer keep your eyes and ears peeled for the many species of birds that can be both seen and heard, you may even see something that you have never seen before. Where do beaver live in Rocky Mountain National Park? Researchers at Colorado State University conduct occupancy surveys to answer this question. Beaver are keystone species that play a major role in wetland ecosystem health and function. Known as “ecosystem engineers,” beaver help to create and maintain important wetland complexes through dam building and foraging. Beavers were once common throughout Rocky Mountain National Park (RMNP) but their population declined dramatically during the past century due to trapping, removal, and habitat loss. Because of their role as ecosystem engineers, increasing beaver populations is an important part of wetland restoration efforts outlined in the park’s Elk and Vegetation Management Plan and the Kawuneeche Valley Restoration Collaborative (KVRC). Signs of Beaver Occupancy and Activity Current knowledge of the park’s beaver populations is limited to a handful of locations. To increase this understanding, researchers from Colorado State University are surveying the main tributaries of the Colorado River for signs of current and historic beaver activity in the Kawuneeche Valley. These occupancy surveys can help managers understand the density and distribution of both current and historic beaver populations. Signs of beaver activity include chewed stems, lodges, active and historic dams, and food caches. Signs of beaver activity from left to right: Recently chewed willow stems. A beave lodge made of sticks and mud. An active beaver dam. A food cache of aspen stems in the water. NPS Photo. Food cache photo courtesy of J. Sueltenfuss Habitat Quality Assessment Throughout the Kawuneeche Valley, the research team also documents vegetation characteristics and browse to assess the quality of beaver habitat there. Vegetation characteristics include type and proportion of shrubs present (willow, alder, and/or birch), shrub height and canopy cover, and shrub health. The amount and type of browse by beaver, elk, and moose are also documented. By comparing habitat quality data for areas with past, present, and no beaver activity, researchers may be able to predict conditions that do or do not support beaver occupancy. This information can be used by managers to inform the type and location of different wetland restoration strategies. Funding for this research comes from the Rocky Mountain Conservancy. Their support makes projects like this possible. by Scott Rashid, Director of Colorado Avian Research and Rehabilitation Institute (CARRI) There are four species of small owls that reside in and around Rocky Mountain National Park (RMNP). The Boreal Owl, Northern Saw-whet Owl, Flammulated Owl and the Northern Pygmy-Owl. All these owls are secondary cavity nesting species, which means that they need to nest in a cavity but cannot create one themselves. Therefore, they need to use an abandoned woodpecker cavity or a nest box that has been provided for them. Apart from the Flammulated Owl, these owls can be found in the area year-round. The Boreal Owl is often found in the Boreal Forest above 9000 feet, the Northern Saw-whet can be found in a multitude of habitats form just below tree line to the foothills. The Northern Pygmy-Owl has a bit more preferred habitat, as they prefer a mixed forest type that consists of aspen, fir, spruce, juniper downed logs, small openings within the forests and a water source. The diminutive Flammulated Owls winter in Mexico and nest up here where they feed primarily on insects, including moths, beetles, and crickets. The Boreal Owl feeds upon voles, mice, small birds and large insects. The Northern Saw-whet prefers deer mice but will also take a few voles and occasionally a bird or two. The Northern Pygmy-Owls have a more varied diet and consume voles, chipmunks, small to medium-sized birds, and nestlings. The Northern Flicker, the largest woodpecker in the area and is the bird that constructs the cavity that these owls prefer. Northern Flickers create a cavity that has a roughly three-inch entrance hole and is about a foot deep. That appears to be sufficient for each species to raise their families. Northern Pygmy-Owls and Northern Saw-whet Owls prefer a nest cavity that is close to water. In many cases, these birds will choose a nest that is within a few yards of a water source, which could be a creek, stream or pond. This is because both species often capture creatures as large if not larger than themselves, and often get bloody. Having a water source near their nests affords them the luxury of bathing when dirty. Clean feathers help keep the owls warm and dry. Northern Saw-whet Owls have a territory that is about 400 yards, where the Northern Pygmy-Owl has a territory that is about ¾ of a square mile. The Boreal Owl seems only to defend the nest tree and not a territory. The Flammulated Owl has a rather tiny territory as they feed upon insects that are often much more numerous and easier to capture than small birds and mammals. Male Northern Saw-whet Owls begin soliciting a female in January, and begin nesting in March. Boreal Owls often begin calling for a female in February and being nesting in March or April. The Northern Pygmy-Owl begins courtship in mid-February and start nesting in late April, early May. The Flammulated Owls Begin arriving here in Late April and begin nesting in May or June. All the owls raise between two and seven owlets. If they nest in a natural cavity, they usually raise two to three owlets, because a natural cavity frequently is so small it cannot fit more than two owlets and the adult female. If they use a nest box, which is much larger than the natural cavity, they can raise as many as seven. The young of these owls remain in their cavities for about four weeks before they fledge. After fledging they remain with their parents for about a month before moving out on their own. This movement often occurs in July or August depending upon when they hatched. Each fall, after dark, researchers around the country broadcast the calls of the owls and set up a series of mist nets to capture the owls as they move in their wintering grounds. We operate one of those research stations in RMNP where we capture and band both Northern Saw-whet Owls and Boreal Owls. The reason for banding the birds is to gain insight into where the birds move to and how long they live. Due to the birds being nomadic, we have only had three Northern Saw-whet Owls recaptured. One Northern Saw-whet Owl was banded in Pinewood Springs, about 15 miles east of Estes Park and recaptured in Estes Park two years later. Another bird was recaptured where it was banded in Estes and the third was banded in Estes and recaptured in Eastern Pennsylvania. Except for the Flammulated Owls, the owls are vocalizing now and can be heard calling for mates. The Northern Pygmy-Owl is active during the day, and the others are active after dark. Hopefully you can get out this spring and hear/see one or more of these wonderful creatures. by Scott Rashid To see and read more from Scott visit his website Colorado Avian Research and Rehabilitation Institute There are birds that spend the winter in Rocky Mountain National Park (RMNP), including Townsend’s Solitaires, Black-billed Magpies, Pygmy Nuthatches, Clark’s Nutcrackers, American Robins, Canada Jays, rosy-finches, and Common Ravens. Several species leave the park to spend the winter in Estes Park to find bird feeders, often staying near them feeding until spring. As Spring arrives, many avian species begin arriving in the area. Over the years, there have been more than 300 species documented either passing through Estes Park and RMNP, or nesting there. We are very familiar with many of these including Black-Billed Magpies, Steller’s Jays, House Finches, Cassin’s Finches, Cooper’s Hawks, Pine Siskins, Lesser Goldfinches and more. There are many areas in and around the park where multiple species can be seen. One of the best locations to see birds is Lake Estes and the surrounding area. On the west end of Lake Estes is a bird sanctuary where more than 305 species have been documented. Many of those use the sanctuary for resting and feeding before moving off to their nesting grounds, others will nest there. The list of birds that simply pass through in the spring includes Tundra and Trumpeter Swans, Blue-winged Teal, Rudy Duck, Redhead, Killdeer, Bobolink, American Dipper, Sharp-shinned Hawk, MacGillivray’s Warbler, Orange-crowned Warbler, Franklin’s Gull, Ring-billed Gull, California Gull, Wilson’s Snipe, Peregrine Falcon, Prairie Falcon, Eastern and Western Kingbird, Roug-winged Swallow, and many more. Lake Estes and the surrounding area including the dog park, golf course and the marina are great places to search for birds of different species. For example, species including Sandhill Cranes, Killdeer, Long-billed Curlews, Prairie Falcons, Red-tailed Hawks, Savanah, Lincoln’s, White crowned and White-throated Sparrows, are frequently seen on the golf course. Common Loons, Western Grebes, Clark’s Grebes, Wilson’s Phalaropes, Spotted Sandpipers, White-faced Ibis’ and Canvasbacks have been seen from the marina swimming in the lake. The baseball field, playground, and dog park are good for sparrows, including Lark Buntings, Clay-colored Sparrows, Brewer’s Sparrows, Painted Buntings, Lazuli Buntings, Western Meadowlarks, Gray Catbirds, Brewer’s Blackbirds, Yellow-headed Blackbirds and Mockingbirds. The species that nest in the sanctuary include Cedar Waxwings, American Robins, Canada Geese, Mallards, Pygmy Nuthatches, Common Grackles, Pine Siskins, Warbling Vireos, and Spotted Sandpipers. The waterfowl (ducks and geese) often nest on the ground near the water, the waxwings nest along the river, the nuthatches construct their cavities in the trees along the creek and the American Robins and Warbling Vireos construct new nests yearly in different locations. Within RMNP, many species of raptors migrate through. These include Swainson’s Hawks, Ferruginous Hawks, Golden Eagles, Bald Eagles, Broad-winged Hawks Merlins, and American Kestrels. Other species that move through the park include warblers like the Bay-breasted Warbler, Palm Warbler, Blackpoll Warbler, Magnolia Warbler and more. Other species that have been documented passing through include American White Pelicans, Double-crested Cormorants, Franklin’s Gulls, Marbled Godwits, Bonaparte’s Gulls, Common Goldeneye, Lazuli Buntings, Lark Buntings, Harris’s Sparrows, and Gray Catbirds. The area has had multiple rarities seen including the Baltimore Oriole, Black-throated Sparrow, Black Phoebe, Hooded Warbler, Prothonotary Warbler, Great-crested Flycatcher, Common Redpoll, Summer Tanager, Rusty Blackbird, Painted Bunting, Eastern Bluebird, Yellow-billed Cuckoo, Lesser Nighthawk and the Golden-crowned Sparrow. Birds have wings and fly very well, which often means that a rare species can show up almost anywhere. As many rare birds have been seen in and around Estes and RMNP. It is a good idea to get out and search for birds, you may find something rare. by Marlene Borneman In 2015 Rocky Mountain National Park celebrated its 100th birthday! Three weeks ago, I celebrated my sixty-eighth birthday. I’m learning that with the aging process comes both physical and emotional scars. I have an appendix scar, back surgery scar, in-situ melanoma scar, scar from childhood slide accident and a few other minor scars. The deaths of my parents, my sister, dear friends and a divorce left me with emotional scars. I have healed and live a rich life in spite of these scars. Rocky has it share of scars too from beetle kills, floods, fire, and even initials carved into aspen trees.

2012 there was the Cub/Spruce Canyon fire. Rocky has a lot of dead, decaying trees building up fuels but not contributing much to new growth. Fire turns them into ashes and releases nutrients into the soil, thus making the soil healthy again. Fires also destroy insects. Fires open up the canopies so sunlight once again can reach the forest floor. New plants grow providing habitat and food to various animals. I see many slopes of Lodgepole pines thickly packed in the Park not leaving much room for anything else to thrive. Lodgepole pines even need fire for their own survival. The Lodgepole cones are sealed with a thick resin sealing the seeds in tightly. Only very high temperatures like produced from fires can open the cones up so seeds can be dispersed. In no time seedlings start popping up in the rich soil provided by fire. New growth will happen.

by Marlene Borneman The fossil record indicates that orchids may have coexisted with dinosaurs! The orchid family is the largest family of flowering plants in the world, approximately 30,000 species. So, it is only fair that approximately 26 species get to call Colorado home. Colorado’s native orchids are terrestrial orchids, referring to growing from the ground in soil. They range from a few inches to over a foot high. Since Rocky Mountain National Park is my backyard, I’m only going to tell the story of orchids that grow in the Park and the Front Range.

I also find how they grow mind-boggling! I will attempt to keep this simple, but remember native orchids are anything but simple! Orchid seeds are extremely minute and can number into the thousands in one single capsule. Because orchid seeds are so minute, they have no food reserves to germinate and are totally dependent on fungus for nutrients during the early stages of growth. Native orchids need a relationship with a variety of fungi to germinate and grow, for some orchids through maturity.

Blunt-leaf Orchid is uncommon in RMNP. It is another orchid I have only seen on the west side. 3”-9” high with one leaf at the base of the plant. The flowers are small and white-greenish in color.

A little trivia …What orchid has the most economic use today? The vanilla orchid. Of course, it does not grow in Colorado! However, some wild orchids found in the Rockies were once used as a food source or for medicinal purposes. For example, the bulbs (corm) of fairy slipper orchids were cooked by Native Americans for their rich buttery taste. The Paiutes made tea from the dried stems of coralroot orchids which was thought to build up the blood. Yes, believe it or not, there are folks out there who read flower guidebooks/websites and social media to locate native wild orchids to dig up in an attempt to transplant. For this reason, the location of orchids should never be made public. It is a rite of passage for anyone truly dedicated to observing and preserving native orchids to search habitats on their own and earn finding orchids. Only nature knows where to “plant” these orchids for success, so don’t even think of transplanting. Appreciate the orchids when you find them and let others enjoy their magical beauty, too. I just take a bazillion photos. My intention is not only to amplify your curiosity but also your respect for these vulnerable plants. Protect them. Suggested reading: The Orchid Thief by Susan Orlean Those Elusive Native Orchids of Colorado by Scott F. Smith Adopt the pace of nature: her secret is patience. Ralph Waldo Emerson Dreaming is okay while “Staying in Place.” I am dreaming of long hikes with meadows chocked full of wildflowers, a slope of yellow avalanche lilies, and a massive clump of calypso orchids thrown in for good measure. I‘m learning patience, knowing these gifts are weeks away and that maybe my favorite spots will be inaccessible. For those who know me well, understand I have not always had a passionate relationship with Colorado native plants.

Wildflowers attract pollinators by boasting strong fragrances, bright colors, and convenient landing platforms. Bees, butterflies, flies, beetles, other insects, as well as hummingbirds come to mind. Colorado is home to 947 species of bees, most of which are native to the state. Colorado has 250 species of butterflies and over one thousand species of moths. And don’t forget eleven species of hummingbirds! Do you know how to distinguish a moth from a butterfly? Looking carefully at the antennae structure is a good start. Butterfly antennae have a ball or club shape swelling at the tips. Moth antenna lack the swelling at the tips and instead have feather-like structures along the antennas.

A few pollinators have only one host plant on which to lay eggs that hatch as caterpillars. One amazing example is the interdependence between the Soapweed Yucca, Yucca glauca, and the pronuba moth, Pronuba yuccasella, commonly called the yucca moth. Soapweed yucca is a common species of yucca along the Front Range. Pollination of soapweed yucca is dependent upon the yucca moth and the yucca moth is dependent on the plant as a food source.

The familiar yellow stonecrop (Sedum lanceolatum) is the host plant for the Rocky Mountain Parnassian Butterfly (Parnassius smintheus). Yellow stonecrop grows profusely in Hollowell Park making it a reliable place to spot the parnassian butterfly. I find the best time to photograph this butterfly is in the early cool morning hours before the butterflies are warmed by the sun.

Monarch butterflies lay their eggs on milkweed plants, no other plant. Monarch caterpillars only eat milkweeds. Monarch caterpillars have adapted to tolerate and use toxins from the milkweed as a defense from their predators—an advantageous survival skill.

It has been so satisfying for me to discover where plants grow, when they bloom, and how they are related to each other. Often a new sighting leads to more questions than answers giving me motivation to seek more time in the field. Rocky Mountain National Park offers countless free learning opportunities. Don’t let them pass you by…get out explore, observe, and learn. Marlene Borneman is the author of Rocky Mountain Wildflowers 2Ed. and The Best Front Range Wildflower Hikes, and Rocky Mountain Alpine Flowers, published by CMC Press. They can be purchased Here by Marlene Borneman One of my favorite quotes: Where flowers bloom, so does hope. -Lady Bird Johnson In this time of uncertainty, I need something reliable and upbeat to look forward to in the near future. My husband and I have cancelled our spring trips to California and Arizona. So, I decided to focus on getting out and searching for early budding native plants. Thoughts of blooming wildflowers bestow on my soul an absolute sense of peace and joy. Vivid memories of past wildflower seasons energize me while providing some normalcy to my “new” routine. In this stay-at-home environment we find ourselves in, I’m getting out my notes jogging my memory about what will be blooming when and where in the coming weeks in and near RMNP. Our native wildflowers will come up no matter what and not disappoint. I remind myself that native plants are resourceful, resilient, hardy and persistent.

You will be so prepared for summer with the hope of exploring in Rocky once again. For now, I’m good with searching for those first flowers of the season wherever I can. Here are a few common spring wildflowers you can start looking for now through June.

The Stemless Easter Daisies ( T. exscapa) have larger flowers and lack the mass of hairy tufts on the bracts. The bright white flowers are easy to spot on sunny hillsides. I find it satisfying to identify a plant with confidence. Be inspired to use this time for learning Colorado native wildflowers and get out where you can in search of promising displays of native plants. Remember, we live in a mind-blowing part of the world. Take pleasure in Colorado’s sunshine, experience the challenge of botanizing all while exercising your mind and body. Please keep in mind you don’t have to be a botanist to use botany. Don’t forget your camera, hand lens and wildflower guidebooks on your explorations. You can purchase these outstanding Wildflower Identification guidebook from: Rocky Mountain Conservancy, click here. Colorado Mountain Club, click here. |

"The wild requires that we learn the terrain, nod to all the plants and animals and birds, ford the streams and cross the ridges, and tell a good story when we get back home." ~ Gary Snyder

Categories

All

“Hiking -I don’t like either the word or the thing. People ought to saunter in the mountains - not hike! Do you know the origin of the word ‘saunter?’ It’s a beautiful word. Away back in the Middle Ages people used to go on pilgrimages to the Holy Land, and when people in the villages through which they passed asked where they were going, they would reply, A la sainte terre,’ ‘To the Holy Land.’ And so they became known as sainte-terre-ers or saunterers. Now these mountains are our Holy Land, and we ought to saunter through them reverently, not ‘hike’ through them.” ~ John Muir |

© Copyright 2025 Barefoot Publications, All Rights Reserved