|

Notes from the

Trail |

|

The History Behind the Names of Popular Destinations in Rocky Mountain National Park By Jamie Palmesano, Brownfield’s all photos by Jamie Palmesano When you hike Rocky Mountain National Park, you're moving through a landscape of jagged peaks, roaring waterfalls, and shimmering lakes. You're also walking through history—a living museum of stories preserved in the names carved onto trail signs and listed on maps. Behind the summits and streams is a tale of exploration, tribute, or natural wonder. Each step is a bit more meaningful when you know the stories behind the landscape. Rocky Mountain National Park was officially established on January 26, 1915, after years of advocacy led by naturalist Enos Mills and other conservationists who recognized the need to protect this extraordinary wilderness. Long before it became a national park, the area was home to Native American tribes, including the Ute and Arapaho, who traveled, hunted, and lived among these rugged landscapes. With its designation, RMNP became one of the earliest national parks in the United States, preserving a stunning diversity of alpine tundra, dense forests, beautiful lakes, and soaring peaks for future generations. Today, Rocky Mountain National Park spans 415 square miles and welcomes millions of visitors each year, offering a timeless reminder of America’s natural beauty. Rocky Mountain National Park is home to approximately 125 named peaks — with elevations ranging from just over 8,000 feet to the park’s tallest summit, Longs Peak at 14,256 feet. There are over 60 peaks above 12,000 feet. There three main ranges in the park:

Longs Peak and the Estes Cone. Longs Peak and the Estes Cone. PEAKS Longs Peak - Named for Major Stephen H. Long, who led an 1820 expedition into the Rocky Mountains. Although Long himself never climbed the peak, his name became forever tied to this towering 14,256-foot summit—the only "fourteener" in northern Colorado. Mount Meeker - This neighbor to Longs Peak honors Nathan Cook Meeker, a visionary who helped found the Union Colony in Greeley, Colorado. His tragic death during the Meeker Massacre of 1879 adds a somber note to the mountain's story. Estes Cone - Joel Estes, a Kentucky-born pioneer, discovered and settled the Estes Valley in 1859. Estes Cone, a striking peak to the south, bears his name as a testament to his influence on the area's early development.

Rocky Mountain National Park boasts approximately 147 named lakes, encompassing a diverse array ofof alpine and subalpine bodies of water. These lakes range from easily accessible spots like Bear Lake to remote backcountry gems such as Lake Nanita. Notably, many of these lakes are glacial in origin, nestled beneath the park's towering peaks and offering stunning reflections and serene landscapes. Rocky Mountain National Park is home to over 30 named waterfalls, each offering unique beauty and varying levels of accessibility. These waterfalls are scattered throughout the park, with some easily reachable via short hikes, while others require more strenuous treks into the backcountry. Notable examples include Alberta Falls, Adams Falls, Ouzel Falls, and Chasm Falls, among others. Many of these waterfalls are particularly stunning during the spring and early summer months when snowmelt feeds their cascades.

landscape. The name preserves a rare Native American place name still in use today within the park. A fun fact is that in 2022, Lake Haiyaha gained extra fame when a rare event (rock flour runoff from nearby glaciers) turned its waters a striking turquoise color. Bierstadt Lake - Named in honor of Albert Bierstadt, a 19th-century landscape painter known for his dramatic portrayals of the American West. Though Bierstadt never painted this specific lake, his work inspired a generation to value the wild beauty of places like the Rockies, fueling early conservation movements. Sprague Lake – Honors Abner Sprague, an early homesteader, guide, and lodge owner in the Estes Park area. He was a strong advocate for national park status. The next time you lace up your boots and head into the park, take a moment to notice the names on trail signs and maps. Each one is a story, an echo, a whisper that these wild places keep the memories of old alive and well. And by hiking them, you honor the legacy of those who understood the magnificence of this remarkable land.

0 Comments

Trails Correspondent Marlene Borneman reports in on her recent trip to the West Side Of Rocky Mountain National Park: West Side RMNP This past week my husband and I got to spend time on the west side of RMNP. Please do not misunderstand when I say we have held the west side of Rocky special in our hearts for many years. We enjoy every square inch of Rocky from corner to corner. However, as soon as Trail Ridge Road opens in the spring until it closes in the fall, we hike, climb and backpack as much as possible on the west side of the divide. There is something about fewer trails, remote lakes/peaks and the sheer ruggedness that is a strong pull. The west side of the divide receives more precipitation resulting in lush, captivating forest, powerful waterfalls, vast meadows and a variety of plant life. Summer 2020 was no exception. We did several cross-country hikes and backpacking trips to remote areas. I’m pleased we took the time and effort to make these trips happen and fully took in all that surrounded us. Who knew what was to happen in the coming weeks that would dramatically take that away? I read reports and have seen a few photos of the trailheads from the fire damage, but nothing prepares you for hiking/snowshoeing the trails that are affected by the Troublesome Creek fire! The blacken sticks on the hillsides, charred lichen on rocks, the private cabin in Summerland Park along the North Inlet Trail destroyed. I worry about the streams; will they be healthy? I feel much discomfort, but strangely also comfort in nature’s healing. I am thankful for what the fire did not take away. Much of the Never Summer Range is intact, Timber Lake Trail, Colorado River Trail, Holzwarth Ranch intact. I saw bright spots among the destruction; snow on the ground and frozen ice crystals that will nourish plant life, a green ponderosa pine sapling, , the sunset over Mount Craig and Grand Avenue with shops and restaurants open for business. Thank you Snowy Peaks Winery for sponsoring Notes From the Trail Visit : www.snowypeakswinery.com by Marlene Borneman In 2015 Rocky Mountain National Park celebrated its 100th birthday! Three weeks ago, I celebrated my sixty-eighth birthday. I’m learning that with the aging process comes both physical and emotional scars. I have an appendix scar, back surgery scar, in-situ melanoma scar, scar from childhood slide accident and a few other minor scars. The deaths of my parents, my sister, dear friends and a divorce left me with emotional scars. I have healed and live a rich life in spite of these scars. Rocky has it share of scars too from beetle kills, floods, fire, and even initials carved into aspen trees.

2012 there was the Cub/Spruce Canyon fire. Rocky has a lot of dead, decaying trees building up fuels but not contributing much to new growth. Fire turns them into ashes and releases nutrients into the soil, thus making the soil healthy again. Fires also destroy insects. Fires open up the canopies so sunlight once again can reach the forest floor. New plants grow providing habitat and food to various animals. I see many slopes of Lodgepole pines thickly packed in the Park not leaving much room for anything else to thrive. Lodgepole pines even need fire for their own survival. The Lodgepole cones are sealed with a thick resin sealing the seeds in tightly. Only very high temperatures like produced from fires can open the cones up so seeds can be dispersed. In no time seedlings start popping up in the rich soil provided by fire. New growth will happen.

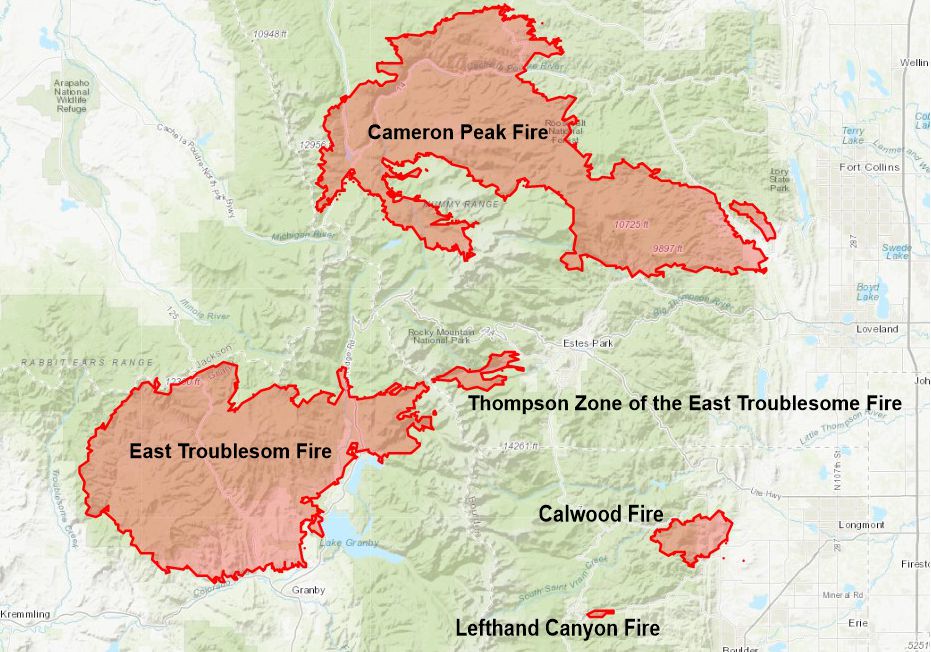

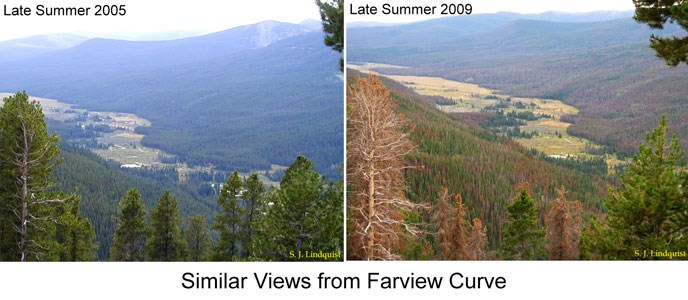

by Barb Boyer Buck The fires surrounding my home in Estes Park caused me to evacuate for a time with my parents; experiencing the mass exodus under midday dark-orange skies with suffocating smoke and ash is something I won’t forget soon. Wildfire is common in the wilderness of the Rocky Mountains but this ongoing situation is unprecedented. The Cameron Peak Fire started in the Arapaho and Roosevelt National Forests, less than 100 miles north of Estes Park, on August 13 when the Pine Gulch Fire, 18 miles north of Grand Junction, had already burned more than 137,000 acres. Pine Gulch was declared the largest wildfire in Colorado’s history until Cameron Peak grew much larger; today, the Cameron Peak Fire has grown to 208,913 acres with 89% containment. This is the equivalent of nearly half of the acreage contained in Boulder County, or more than twice the size of the City of Denver. On August 14, the Williams Fork Fire started 10 miles southwest of Fraser, Colorado, and has burned nearly 15,000 acres with 76% containment. On October 14, the East Troublesome Fire ignited north of Hot Sulphur Springs, west of the Continental Divide. High winds pushed the fire more than 100,000 acres overnight, extending north into the west side of Rocky Mountain National Park. Grand County Sherriff Brett Schroetlin reported this fire growth as “unheard of. This is the worst of the worst of the worst,” he said, in an interview with NPR. Today, the East Troublesome Fire’s footprint is 193,804 acres with 37% containment. On October 17 three miles northwest of Jamestown, the Calwood Fire started. It is currently 76% contained and has consumed more than 10,000 acres. The Lefthand Canyon fire began on October 18, one mile west of Ward and consumed 438 acres of brush and timber before it was 100% contained on Oct. 22. Also on Oct. 22, the East Troublesome Fire experienced another “unheard of” growth, jumping over the Continental Divide in Rocky Mountain National Park, miles of rock and tundra that usually provide a natural fire break. As of today, this spot fire, named the Thompson Zone, has burned 4,346 acres just west of Estes Park, within the boundaries of the national park. Mass evacuations for the Town of Estes Park began on October 22, when the two leading edges of fire from the Cameron Peak and the Thompson Zone/East Troublesome fires had grown to within five miles from the north and west sides of town. The entire Estes Valley was on mandatory evacs by the morning of Saturday, Oct. 24. Highways 36 and 34 were closed to incoming traffic; all of the businesses were closed. Visitors were not welcome. This has never before happened in this tourism-supported community, not even during the 2013, 1,000-year flood. I had been struggling with the smoke that has been ever-present since the Cameron Peak fire began. I have moderate to severe asthma and I quickly invested in air purifiers and visited the doctor for stronger asthma meds and I’ve lost work on bad air-quality days. On Saturday, October 17, I retreated to my parent’s house in Johnstown for a much-needed break from the smoke. I stayed until I had to go back to work in Estes Park on Wednesday, Oct. 21. The very next day, everyone was ordered to evacuate so my cat and I escaped again. I am breathing much, much easier (physically and emotionally) here at my parent’s house but I must return to Estes Park soon, even though the two fires closest to Estes Park are not fully contained. And are still less than 10 miles from my home. For most of us who evacuated from Estes Park, the inclination is to chalk it up to another 2020 debacle. But what set up these perfect firestorms in Colorado started much earlier than this year. It is the culmination of at least 30 years of conditions caused by climate change that are not likely to be fixed by fully containing the last that is fire burning. In an interview with KWGN News on October 23, Colorado’s governor Jared Polis said the wildfires are a combination of “climate change and increased population and utilization of public lands.” Way back in 1996, the Rocky Mountains experienced a cyclical, natural event: the beginning of a pine-beetle infestation. Pine beetles are insidious creatures, boring into the bark of lodgepole pines and slowly killing them. Pine-beetle infestations occur every 30 years or so, but this one was different. This one LASTED for nearly 30 years because of the increasingly warm climate. If it doesn’t get cold enough in the winter, the beetles don’t die and continue their destruction of our forests. A pine tree that has been infested with pine beetles is killed from the inside out. Their needles turn red and eventually fall off; what’s left become “gray ghosts.” Since 2009, these gray ghosts have been more and more prevalent in Rocky Mountain National Park; 95 percent of Colorado’s lodgepole pine forests were killed during this infestation which began to abate in about 2015. These dead, yet standing, trees also create extreme fire danger. Now, add the extended drought Colorado has been experiencing and it becomes clear, it would take only a few years to create the tinderbox that is burning all around my town. According to RMNP’s website, Colorado has been experiencing warmer-than-normal conditions for the past decade. But those conditions still would not have been enough to cause the situation in and around Estes Park right now. The second part of Polis’ statement on the wildfire’ intensity must be taken into consideration. In 2019, Rocky Mountain National Park hosted 4.7 million visitors, most coming through the community of Estes Park. The impact of human utilization of our wilderness is a significant threat, especially when regulations in place to limit harm are ignored. When COVID19 became a significant threat in the spring of this year, it was essential to limit the number of visitors to the national park and Estes Park’s mayor requested it be closed. When the Park reopened in late May, NPS soon implemented a timed-entry reservation system to limit vehicles entering to numbers that were last experienced in 1996. But the reservation system ended on October 12 and even before that, thousands of visitors crowded the Park after 5 p.m. (when a reservation was no longer needed) to watch the elk rut season which began in early September. The National Park, forest service, and Estes Park has had a fire ban since August 15, yet every fire I mentioned above was believed to be caused by human activity except for the Pine Gulch Fire, which was caused by a lightning strike on July 27. The exact causes for all of the other fires are still under investigation but the blame has been laid squarely on humans. Estes Park lifted or downgraded evacuations in town last week but Rocky Mountain National Park and all forest service land surrounding town is closed to all access, except for firefighters. There was a caveat to lifting evacuations orders and to visitors coming back into town: “be prepared to leave at a moment’s notice.” 422 structures have been lost in the East Troublesome Fire to date; it is still unknown how many were lost in the Cameron Peak Fire. Residents in Glen Haven and its surrounding communities were only allowed to return home yesterday. There has been some progress on the containment of the two fire’s edges that directly threaten Estes Park, and visitors are being welcomed back into town. But without the National Park or the Forest Service to recreate in, the only choice is to visit the business establishments in town and COVID19 cases are increasing in all communities in Colorado. Another spell of dry, warm, and windy conditions is predicted for this coming week. To date, the East Troublesome and Cameron Peak fires have burned 29,000 acres of RMNP - the most acreage burned in any fire or combination of fires in the same year since the Park was established more than 100 years ago. If 2020 is teaching us one thing, it’s that we must always pay for our actions. If we don’t take care of our environment, it will take care of itself. No consideration will be given to the fact that humans live here, too. Wildfire serves to clean out the dead growth in our forests, but the extent of wildfire in northern Colorado this year is more than a warning. It signals a significant climate shift and we must all take heed or humans will be another casualty of Nature’s wrath. The following slide show features pictures of the destruction caused in RMNP by the East Troublesome Fire between Oct. 23-25. Photos courtesy of RMNP or Larimer County Sheriff (as noted): Story and photos (except the last one) by Barb Boyer Buck Before I go into details of the Cow Creek Trailhead hiking opportunities, there are several things to keep in mind. First, parking is extremely limited and fills up quickly. Roadside parking, or parking in a homeowner's driveway is strictly forbidden. Respectful usage of this trailhead is a must as there are sensitive ecosystems, private land, active researchers, and lots of wildlife also inhabiting the Cow Creek Valley. The McGraw Ranch Road, which is your only access to this trailhead, is a dirt road with mild washboards and can be easily accessed from Devil's Gulch Road, on the north side of Estes Park. If you want to hike this trail, my advice would be to go very early in the morning, or late afternoon. Please remember in the summer months, afternoons often bring thunderstorms and several portions of this hike crosses wide-open meadows. It is not advisable to hike during a thunderstorm, lightening strikes are a very real possibility. If you find yourself wanting to hike this trail at any other time of the day, the best thing to do is have someone drop you off at the trailhead; however, cell phone reception is pretty much non-existent in the area. If you decide on this option, have a plan to meet at a specific time with the understanding that idling cars waiting to pick up delayed hikers are also not permitted. Instruct your driver to check back occasionally if you are not there when you expected to be.

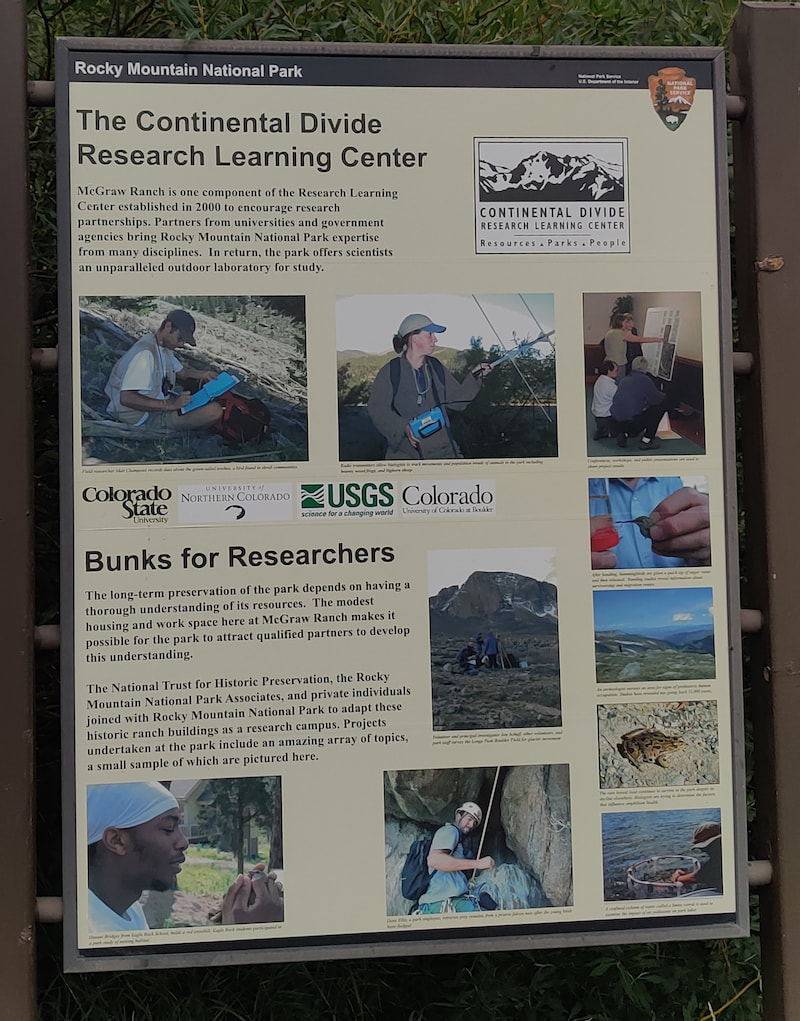

The site of the old McGraw Ranch still has buildings, including one that has been standing since 1871, the original homestead cabin of Harry Farrar. Others were built between 1884-1887, and most of the guest cabins were built between 1935-1936 by Frank and John McGraw (for more history of the ranch's early days, see part one of The Cow Creek Trail, published last week).

Researchers from Northern Colorado, Colorado State University, and the University of Colorado, along with the United States Geological Survey, now use the surrounding land as an outdoor laboratory. Onsite housing, laboratories, meeting rooms, and dining areas for these individuals are provided by the ranch buildings. The renovation of the buildings started in 1999, the culmination of a partnership between the NTHP and several private citizens to restore the McGraw Ranch buildings to their heyday as a guest ranch, between 1936-1955. The research center opened in 2003, becoming an important site to gather significant data in RMNP; Rocky Mountain National Park is designated as a United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural (UNESCO) international biosphere reserve. From butterflies (there are 142 species confirmed in RMNP) to climate change, these studies provide important, scientifically-gathered information for the entire world. I started my hike at dawn, just before 6 a.m., at the research center. Very soon, the trail has an intersection on the right with the North Boundary Trail which branches up and east. The beginning of the way to Bridal Veil Falls was lit with the sun at my back, glorious coloring the late-summer vegetation and a whitetail deer, grazing along the edge of the trail.

The first part of the hike is a beautiful meadow that climbs a bit before it wanders back to Cow Creek. For most of the hike, you can hear its rushing or trickling waters, something I enjoy very much. It's so relaxing. I needed a bit of calming down because I was anxious about taking this hike by myself, the first one with a distance of more 2 miles I've taken on my own since my back surgery. And there was no one else on the trail that early in the morning. Every rustle in the trees had me looking - this is bear country after all! It's also a hunting ground for mountain lions, although it's very rare to see these creatures anywhere near humans. A bit further down the road comes another trail crossing, this time giving you the option to turn left to hook up with the Lumpy Ridge Trail to visit Balanced Rock and Gem Lake.

Just beyond this spot, there are some steep rocks before the trail picks up again. I didn't dare do this on my own so I guess neither horses nor I would get any further. It was frustrating because ED. (more about ED. next week) told me I was essentially there, but I couldn't chance it. Just a few weeks ago, a woman took a tumbling fall, sustaining serious injuries, above Bridal Veil falls (see more info here: https://www.rockymountaindayhikes.com/rmnp-updates.html) So, I ate some fruit, drank some water and started back. I saw several more people on the trail and I was grateful to be coming back. The sun was higher now, and it was starting to get hot. When I passed through the meadows again, the butterflies were flitting all around me, enjoying the late-August sunshine. It took me about five hours to do six miles roundtrip but remember, I stopped to take many pictures along the way. It was worth it and I needed it. It was the first morning without any smoke haze after two days of good rain. The air was clear, the sky was blue and the morning light was perfect. Happy hiking, everyone! by Barb Boyer Buck Imagine it's 150 years ago (I do this all the time). Imagine you have made the long trek via horseback to the beautiful mountain valley of Estes Park. At that time, Colorado was a territory of the US and the land was declared "public" by the Homestead Act. Every piece of the valley that is not already developed is open for homesteading. All you have to do is pick out your 160-acre parcel, "improve" the property, and pay a small registration fee. Put yourself in that scene. What is your personal perspective? Are you a child, part of a family looking for a new home? Are you sick of the towns where you live and want some peace and quiet in the Colorado mountains? Do you fancy yourself a wilderness man or woman, fiercely independent and resourceful? You're itching to live off the land and figure things out for yourself. Whatever your perspective, I'm sure you'll agree. The homesteading narrative is romantic and adventurous. Let's say you’re a big game hunting guide and you marvel at the wide-open fields below you as you crest that final hill over Estes Park. It's the late summer of 1871, and the basin looks mostly dry, with only the snake of the Big Thompson River slicing through it (there was no lake back then). You notice the prime spots along the river were already claimed. Now, suppose you ride north in the valley, where the mountains meet the meadows and the elk are plentiful. Finally, you see it. The Cow Creek Valley. The creeks in this valley have been slicing a sliver out of the surrounding Rocky Mountains for millions of years. Upon investigation, you find the valley is more than wide enough to establish a viable homestead and the entire drainage is covered in lush foliage. Imagine you stop to take a drink from the stream. (Don't do that today unless you treat the water!) These are not the exact circumstances that led Henry Farrar to eventually homestead the area in 1871, but it's probably close. These are the kind of things I like to think of when I talk about hikes in historic sites within Rocky Mountain National Park but when I was a kid, I hated history. I struggled in class to remember dates, names, events. I only fell in love with history while I earned a BA in Anthropology. Suddenly, I found context in past events. I studied possible motivations for historical figures. I found similarities between myself and everyone who came before me. I can imagine myself into the mindset of someone in Estes Park, 150 years ago. In the case of the Cow Creek Valley, I can imagine the stirring excitement of the situation, being given just enough help through the Homestead Act to get myself started in something entirely my own. In reality, Estes Park had long been the hunting grounds for native Americans, a summer stop on their nomadic routes. Just because a place had never been permanently settled, doesn't mean anyone should claim it. It had been a public, shared, space for ten thousand years before the homesteaders arrived. Several buildings near the original homestead near Cow Creek were finished in 1887 after the property was developed with its sale in 1884. The barn, the lodge, the bunkhouse, and two additional cabins started this valley along another journey. It provided water for cows and the family that lived there. I imagine an idyllic scene, exactly how you'd imagine what a Little-House-on-the-Prairie homestead would be like here, in its perfect riparian ecosystem. Bounteous and cozy. I'm an environmentalist, so I understand the damage human development has affected on our ecosystem, but the feeling of adventure, possibility, and excitement is intoxicating. John and Irene McGraw, grandparents of the surviving McGraw lineage, bought the ranch outright in 1909. John set it up so there could never be any debt on it. There was no way any of his kin was going to gamble with the family home by using it as leverage in other concerns. This pioneer tradition of establishing family ranches can be found in nearly every rural town, including those close to a National Park. Frank and his brother John, sons of the senior McGraws, turned the place into a dude ranch in 1936 by building additional cabins, eager to get in on the action so many in the area had at the time by taking in lodgers.

The McGraw family was the backbone of the operation and was living onsite, but everyone had to move to a hotel in Estes Park to make room for the Landon family and his campaign. Secret service personnel were housed in the bunkhouse, the Landon family lived in the lodge. The McGraws would return to the ranch every day to cook for everyone and take them on horse rides. One of the most popular rides was to Bridal Veil Falls. Eventually, this well-trodden path became the Cow Creek Trail.

After Landon's visit, the McGraw Ranch was on the map and the family, eventually including Frank's wife and five daughters, were essential to its success during its 52 years of operation as a guest ranch. In 1988, The McGraw Ranch was sold to the National Park Service and became part of Rocky Mountain National Park. Go to Part Two of The Cow Creek Trail next week when I will describe trail specifics, more historical anecdotes, and explain what the McGraw Ranch buildings are being used for today. Story and photos by Barb Boyer Buck Every summer, I eagerly anticipate the reopening of Old Fall River Road in Rocky Mountain National Park. It usually happens around July 4, depending on weather. This dirt road travels one-way up to the top of the pass, emptying out at the back of the Alpine Visitor’s Center parking lot and Trail Ridge Road (that’s how you get back down). In places, the grade is as steep at 16% and switchbacks on the road can reach as tight as 20 degrees radii. It’s narrow and rocky, tends to become riddled with fairly deep potholes, and has very steep drop-offs (with no guardrails) on one side for most of the way. Yet, my little 2-door, front-wheel drive car can manage it easily. In fact, wider and heavier cars have a much more difficult time. For the time being with my knees in rehab, this is my favorite way to access the sub-alpine forest, which is at its most beautiful this month and next. Every week, the sights, smells, and sounds are different, making it a shame to limit yourself to just one trip. The road closes when the first snows start accumulating at that elevation, usually at the beginning of October. September is a beautiful month to drive it as well, with the aspen leaves in full color (not just gold, but often orange and red, too) and the tundra becomes a sea of rust-gold. Old Fall River Road travels from Endovalley (near the Alluvial Fan), where it passes through several ecosystems as you travel up. These include the montane, subalpine, and alpine. In some spots, rich riparian areas offer a rare east-side Rocky look at the sights and sounds of this ecosystem. You move from dense forests to tundra in only 11 miles. This will be one of the longest 11-mile drives you will take. But especially if you’re used to city traffic logjams, you couldn’t ask for a more pleasant delay. There are plenty of places to stop and I recommend stopping at all of them, if you can. The first major attraction is Chasm Falls. This amazing water feature can be seen with a very short hike from the pullout, making it a rare experience for everyone. These types of waterfalls are common in the backcountry, especially just before you approach treeline, accessed by arduous hiking in most cases. There is a spectacular hike (as I remember, I hiked it long ago) that can be accessed from this road at Chapin Creek Trail. There is space for approximately 10 cars in the pullout for the trailhead, so it’s best to go up very early. This trail is 6.6 miles to Chapin Meadows (at the base of Mount Chapin), where it splits to the Mummy Range trail. Several spots to pullout include limited access (foot traffic only) to beautiful forests and the Fall River, which follows the road for most of the way up. Glorious wildflowers, wildlife, lush forests and stunning views greet you the entire way. When its approximately three months of vehicle access is over, you can hike or bike this road (weather permitting). Of course, I love the sights and sounds I witness from my car & the short hikes I do when I stop at certain places. But just as enthralling to me is the rich history of this road. Construction of the road began in 1913 and lasted seven years, with a brief interruption caused by World War I in 1914. When it was finally finished, it connected Estes Park to Grand Lake. When Rocky Mountain National Park was dedicated in the Fall River Valley in 1915, attendees could observe men, using only hand tools, widening the path that Native Americans had weathered for 10s of thousands of years. This actually caused an issue for some of the more refined and prominent representatives at the RMNP dedication. Because at the time, Colorado State Penitentiary inmates, housed in nearby cabins, were the men building the road. (A construction company took over building the road before it was fully extended to Grand Lake.) Congressmen, Colorado’s governor, prominent local businessmen, and local women associations attended the dedication; seeing the convicts carving out the road was the not the proper aesthetic and the men could be dangerous, some thought. In my opinion, seeing slave labor at work was not very palatable for the higher-ups of the time. Another important part of the road’s history is its association to the end of Estes Park’s grand old hotels. Before Fall River Road was opened in 1920, people who came to Estes Park had reached the end of the road, so to speak. They couldn’t travel farther west than Rocky Mountain National Park’s east-facing mountains, unless they climbed over. Hotels on the east side of RMNP such as Elkhorn Lodge (built in 1874), Stanley Hotel (1909), the Crags Lodge (1914), the Baldpate Inn (1917) were designed to have everything a visitor could need. Lodging, food, entertainment, opportunities to relax, and starting points for hunting trips or wildflower gathering were provided by these lodges. (These days hunting and gathering of anything is illegal in Rocky Mountain National Park, it’s a federal crime.) But after Fall River Road finally opened to create vehicle access from Estes Park to Grand Lake, the story changed a bit. Eventually, Estes Park was not the place to stay for weeks or months at a time; it was a place to stop for a few days on the way to points west. Grand Old Hotels gave way to roadside motels, especially in the 1950s and 60s when vehicle travel became America’s favorite pastime. Do yourself a favor and make Old Fall River Road part of this summer's adventure in Rocky Mountain National Park. Be sure your vehicle does well in high altitudes, has a full tank of gas, and my advice is not to drive large vehicles up it, it’s much more difficult that way. But above all, remember it’s only ONE WAY, going up – you will have to take Trail Ridge Road to go back down, either to Estes Park or Grand Lake. By Barb Boyer Buck Rocky Mountain National Park is a wonderland of high-country wilderness. Millions of people from all over the world travel here to experience the beautiful scenery and hike trails every year. Summer is the most pleasant in RMNP with burgeoning wildflowers, a plethora of varied wildlife, and stunning weather – but it’s very important to keep in mind safety concerns and take the proper precautions.

experience, skill, and the proper equipment. Bouldering (climbing without ropes) is properly done only with crash pads & spotters. The best advice would be to keep from scrambling on the rocks at all if you don’t have consistent experience doing so, especially for young children. Wildlife Safety Few things are more exciting than seeing a wild animal in its natural habitat, especially if they have offspring with them. But even though Rocky’s wildlife has become habituated to the presence of humans, serious altercations can – and do! – occur when the proper precautions are not taken.

Preparing for changing conditions. If you’ve ever visited Rocky Mountain National Park in any season of the year, you have probably experienced a sudden thunder-storm that clears up within minutes, or have been pelted with hail only to be unbearable hot shortly after, when full sun emerges again. Weather is extremely changeable and unpredictable in the Rocky Mountains. Lightening strikes happen every year in Rocky, in every location. There are many areas in the park that allow hiking above or at treeline which increases the chances of being struck. Watch for storm clouds forming and plan for reaching shelter if the weather suddenly shifts. Wear layers, including a hat, to protect against the sun even if it is cloudy. Sunscreen is essential as you are about two miles closer to the sun than if you were at sea level. Sunburns can happen even if it’s overcast. Wear the proper footwear and plan for changing trail conditions. A dry, dusty trail can suddenly shift to a snow-packed one and regular hiking boots may not be adequate. Bring boot spikes or snowshoes (in the winter) along with you on your hikes.

Stay away from snow patches on inclines as these can give way to avalanches, any time of the year. Check with a ranger about the level of avalanche danger. Rocks and trees are not always stationary! Things that can cause a tree to fall unexpectedly include damage to the tree itself through fire or flood, disease, and high winds. Rocks can be dislodged by human and wildlife activity. Rockslides are possible in these situations. Streams, lakes, and waterfalls are beautiful and look very inviting. However, rushing streams can be very dangerous, rivers and lakes can be deeper than they look and waterfalls can contain debris. Streamside rocks are often slippery, so special care needs to be taken with children, especially young ones. Untreated water in Rocky Mountain National Park is not safe to drink.

Electrolytes also help replenish what high elevation depletes from your body. People with existing health conditions such as heart and lung disease should be very careful as they ascend in elevation. Hypothermia is a very real danger in almost every season in Rocky. Symptoms are sleepiness, impaired judgment, slurred speech and shivering. Lack of data reception You can't count on your phone to communicate dependably, or internet service while in RMNP. Be sure someone outside the Park knows where you are and when you expect to return. Protect from getting lost while hiking Rocky by downloading our free app, which utilizes GPS to power its trail maps, available here: GPSMyHike.com A "perfect" day in RMNP can turn into a serious situation quickly, so be sure to follow these basic safety precautions while visiting this beautiful national treasure. What’s it going to take to get to the trailhead in Rocky Mountain National Park? A little advance planning and some patience. Rocky Mountain National Park has so many fantastic hiking trails that are very popular. Over the years, getting to these trails have become increasingly more difficult with increased visitation. The line of cars to get into the Park are longer and finding parking often involves using shuttle busses. And even then, sometimes the parking spaces are just used up!

Park officials have tried to respond. It’s now possible to Park your car east of the Town of Estes and catch the Hiker Shuttle that heads you straight into the Park. But, there’s still more work to be done. It would be great if there was a dedicated lane for the shuttle busses to pass the long line of cars waiting to go through the entrance gates, for example. This year, in response to coronavirus concerns, the Park is trying out a reservation system to limit the number of cars entering the Park and spreading the people congestion throughout the day. Last Sunday, I got to try it out. My hiking partner and I decided we would get a reservation to go into the Park between 8am and 10am. I signed up on recreation.gov the previous week and found plenty of spaces available. That may change as people begin to learn about the reservation system.

and once we reached the entrance gate, we flowed though pretty quickly. They wanted to see my reservation and my Park Pass. Our next decision was about whether we should take our chances with trailhead parking or just go straight to the Park-and-Ride lot and take the shuttle, like we ended up doing last week. Just as we were contemplating that question, a flashing road sign notified us the the Bear Lake parking lot was full and to use the Park-and-Ride. Decision made.

risk these days. We were all outside and the masks kind of helped us feel protected. I got a little tickle up my nose and wanted to sneeze. That might bring on some social distancing! I suppressed my sneeze.

The Park is currently running five shuttle busses between the Park-and-Ride and the Bear Lake parking lot. It takes a bus about 30 min to make the round trip. In order to keep people safe while riding the bus, they’re only allowing about 15-20 people on a bus. People were patient while they waited. It looked like the 4th and 5th shuttle bus didn’t come on line until 9:30, so that may have delayed out time. It took us a little over an hour to finally get to the trail head. by Barb Boyer Buck A father fights for a better life for his children, a grandfather spoils them. A father shows his offspring how to be productive citizens of the world by teaching them the valuable lessons he has learned. A grandfather rests on the wealth of his knowledge and experience and shares these, generously and without condition, with his grandchildren. Such are the patriarchs of the Estes Valley, Enos Mills and FO Stanley, the leaders who are credited with the development and the establishment of Rocky Mountain National Park and the Town of Estes Park.

She can be seen from miles East. This striking landmark is named for the man who first spotted her on behalf of the US Government in 1820, Major Stephen Long. But thousands of years before that, Longs and her sister, Mount Meeker (13,911 ft.), were designated the “two guides” by the indigenous people who made what is now the northern plains of Colorado part of their territory. These nomads followed their “guides” all the way up to the top of the Divide, to the alpine tundra which thrives where it’s too high for trees to grow. There, they hunted the now-extinct mountain bison, and elk. It was their summer home, a very fat and sweet season. Longs Peak has inspired a painting by Albert Bierstadt, a photograph by Ansel Adams, amazing prose, countless songs, and thousands of climbers to conquer that unmovable monarch. When he was 14 years old, Mills was sent by his family to seek the “mountain cure” at his relative’s homestead. The Reverend Elkanah Lamb, cousin to Mills’ mother, lived in the Tahosa Valley, south of Estes Park, with Longs Peak towering over it. Ever since and for the rest of his life, this peak consumed Mills’ activities and ponderings. When he first arrived in 1884 he was frail, suffering from an undiagnosed allergy to the wheat his family farmed. (Today, we call that celiac disease.) At first, he couldn’t climb Longs Peak at all. As he regained his health in the mountain air of the Rockies, Enos guided guests to the top of Longs frequently; he summited the peak 297 times in his lifetime. He loved her so much he was eventually inspired to take up the fight for the conservation of the land she sits on. Enos spent winters away from the homestead working at various mining operations until a fire at the Anaconda Copper Mine in Butte, Montana, put him out of work in the fall of 1889. Visitors would not arrive to Longs Peak House (Lamb’s establishment which was later purchased by Mills) until summer, so it freed the young man to travel to places he had never been. While visiting a beach in San Francisco later that year, Mills listened to a speech by John Muir who disparaged the west’s prevailing philosophy of homesteading. People do not have a divine right to the indiscriminate use of surrounding natural resources while establishing a home or eking out a living, Muir positioned. This California naturalist and champion for Yosemite National Park would become his lifelong friend and mentor. Mills soon began to question his choice of employment in the mines. He studied conservation and began writing his own pieces on the subject. When guiding his summer guests around the Estes Valley and up Longs Peak, Mills spoke of the negative impact humans can have on nature. Visitors were chastised for picking wildflowers and encouraged to get out into the wilderness every day of their visit. Eventually he became Colorado’s official snow recorder, snowshoeing the high ridges of the Continental Divide to measure snow-pack with his trusty dog Scotch by his side. He was soon inspired to take on the cause for creating Rocky Mountain National Park. Mills’ original plan for the national park included 1,000 square miles of Colorado’s Rocky Mountains, extending from Colorado Springs to the Wyoming border. But the Rocky Mountains contained valuable minerals, including gold. The Colorado Gold Rush which began in 1858 was instrumental in the formation of the state of Colorado in 1876. There was money to be made from logging as well. Conservation was a very hard sell in the west during the 19th Century. This was a difficult time for Enos Mills, living in the Estes Valley. Local residents – all homesteaders – resented his work in conservation and felt personally threatened by his idea of creating a national park in their backyard. Sewer lines were run onto his land and his cattle were reportedly poisoned. History may look upon Enos Mills as one of the most visionary men of his time, but his neighbors saw him as a dangerous pariah and meted out frontier justice with the conviction of self-made pioneers. Mills began to travel the country and speak on naturalist subjects and the proposed Rocky Mountain National Park. He gained enough support and influence to see his dream realized – America’s 10th National Park was established on January 26, 1915, and dedicated in September of that year. But it only contained a little more than 350 square miles. Subsequent acquisitions grew the Park to what it is today. FO Stanley, “the grandfather of Estes Park,” also came to the area for health concerns – and he didn’t exactly fit in with his new neighbors, either. Estes Park residents first heard of his arrival in the early summer of 1903 when he completed the 16-mile trip from Lyons to Estes Park in less than two hours via the Stanley Steamer, a feat none thought possible. FO invented the Stanley Steamer (a steam-powered motor car) with his twin brother, FE Stanley. They were raised in Kingston, Maine, and these brilliant men are credited with another remarkable invention: dry plate photography. They sold this technology to George Eastman who went on to establish the Eastman/Kodak company. But by the time he was 50, FO suffered from tuberculosis and he left his home with his wife, Flora, to seek the dry mountain air of Colorado. When he first arrived in Estes Park, crowned by the indomitable Longs Peak, he was smitten by its beauty. Imagine the reaction of the earliest Estes Park pioneers when they first saw Stanley sputter into town in his motor car, backed by the wealth of his established family and the many successes he and his brother realized. Within several years, he announced his intention to build a luxury hotel, complete with running water and electricity. This was a crazy plan, thought most of the locals, and viewed his activity with suspicion. But Stanley’s innovative developments proved beneficial for the entire community. To generate electricity, he established a hydroplant at Fall River and built distribution lines from the operation to his hotel. Along the way, he sold electricity to residents by selling them light bulbs. He established the area’s first water distribution system, too, by feeding the waters of Black Canyon creek directly to his hotel via wooden pipes lined with pitch. When the doors opened in 1909, the Stanley Hotel greeted its guests with a stunning view of Longs Peak, a flood of electric lights, and hot-and-cold running water, amenities unheard of in the remote Colorado mountains at that time. It was his kindness and generosity he extended to the children of Estes Park that first earned him the moniker “grandfather of Estes Park.” He would give children trinkets and dimes and would often stop to give them rides in his steam car.

Although both men were initially treated with attitudes ranging from skepticism to outright hostility, Mills and Stanley are now viewed as the most important contributors to area’s development and preservation. As it is can be with any good parent or grandparent, their efforts in guiding and providing for their “children” were misunderstood at the time. In Estes Park this morning, looking at the unspoiled views surrounding Longs Peak, gratitude fills my soul. Thanks, Dad. Thanks, Grandpa. The Mountains Have Seen it All

By Sybil Barnes There’s a saying you might have heard - “The only thing constant is change.” Sometimes I wonder how true that is. When I look up at Longs Peak or Twin Owls or the thumb on Prospect, I can imagine that I’m Patsey Estes or Isabella Bird or Esther Burnell seeing them for the first time. There are many other places in Estes Park and Rocky Mountain National Park about which I can’t say the same. But aside from a radical change in population of both visitors and residents and the associated buildings, roads, and services that go along with that increase, what changes have truly happened here? Let’s start with some of the history we know. Perhaps as a way to escape from the turmoil of the approaching Civil War, Patsey Estes and her family chose to live a hardscrabble life of subsistence ranching in a place with no neighbors. She had followed her husband from a relatively comfortable life in Missouri to this place he had discovered on a hunting trip and thought was beautiful. As far as we know, none of her letters or other writings exist so it’s impossible to say if she shared that feeling. This open space offered sweeping views with no neighbors. Though there was an abundance of wild game and fish to eat, it was a lonely life. The Estes family only had each other and the rare visitor for entertainment. Joel and his sons made trips to Denver to sell meat and skins but Patsey was home with the other children and a million chores. They eventually moved on to New Mexico after selling their “improved” property with its panoramic views from Longs Peak to Eagle Rock. Isabella Bird shared a lot of her feelings when she arrived as one of the first tourists to enjoy the hospitality of Grif Evans and his family. Evans had only moved up the hill from Lyons to take over the Estes holdings and was one of the first to recognize the potential of entertaining visitors as a revenue source. Ms Bird had a horse and was interested in exploring the area both on horseback and on foot. As a visitor, she had few of the responsibilities of providing a home or entertainment. Her writings may have encouraged an Irish nobleman to explore this part of Colorado while he was on a hunting trip to Wyoming. Unfortunately, no known record exists of the guests at Lord Dunraven’s hotel on Fish Creek. There are a few photographs which show women “taking the air” in front of the hotel. And it is known that the Irish Earl was not accompanied by his wife or daughters on most of his American trips. He spent his days riding and hunting and his evenings with food and drink. His visits were mostly made in the summer or fall but he left a land manager here year round. By the beginning of the 20th century, there was a town forming in the open space that had been named Estes’ Park by the newspaper editor, William Byers. Ranchers like the MacGregors and the McCreerys and the James and Hondius families arrived in the later 1880s and had become used to the conveniences of a general store and weekly mail delivery. More and more dudes were discovering the delights of a summer spent in the cool mountains. Shops selling souvenir photographs were opening at the confluence of the Big Thompson and Fall River in the space between Elkhorn Lodge and the MacGregor holdings. Horses and hiking were the main means of transportation and a pleasant way to explore the area. Other families, including the Spragues and Chapmans had ventured further west and created another small community in what they called Willow Park. Private cabins were built on the eastern hillside with sweeping views of the meadow between the moraines. Fish were abundant in the Thompson River and Frank Bartholf grazed his cattle further to the south on what would become the Bear Lake Road. Flora Stanley first came to Estes Park with her husband in 1909. He saw the potential for growth and development as a summer tourist destination. He had the discretionary income to build a fine hotel and create an infrastructure of utilities for the town that had been platted by Abner Sprague and was being marketed by Loveland businessman C.H. Bond and others. The hotel needed electric lights and indoor plumbing, so Stanley funded a power plant and a sewage system which would serve the entire village. He donated some of his property for public use as a community park and gathering place. Flora had vision problems so she was unable to comment on the view. She was probably delighted that her husband’s respiratory problems were solved by spending summers in the mountains but possibly just as happy to return to Maine for nine months of the year. When Esther Burnell and her sister Elizabeth came west on a summer vacation they discovered another settlement in the Tahosa Valley at the base of Longs Peak. The young women were hired to be nature guides at Enos Mills’ lodge. After a summer spent climbing mountains and identifying wildflowers, Elizabeth went to California to continue her education and Esther stayed to homestead property on the Fall River Road. She married Enos and became the mother of Enda Mills Kiley. After Enos’ untimely death, Esther and Enda carried on his legacy by running the Longs Peak Inn and making sure that his nature writings stayed in print and his ecological philosophy was brought forward through the 20th century. Growth of the town of Estes Park has always been limited by the topography of the area. Many people wanted to visit in the summer but not that many wanted to spend a windy and cold winter here. That changed with the construction of the Adams Tunnel to bring water from the wetter west side to the plains of eastern Colorado. When Bertha Ramey’s family moved from Lyons to start providing insurance and related services to the businesses and homeowners, the land where the Estes family had settled was still a meadow with the Big Thompson River meandering through it. By 1950, that property had been flooded by a reservoir called Lake Estes. Now when visitors make the last turn down Park Hill, they see water reflecting the mountain ranges beyond. Also by the 1950s, a few hundred people had decided to spend the winter months in Estes Park. Many of them worked for the National Park Service. Others spent the slower months getting their tourist accommodations ready for the next season. By the 1970s, young business people were seeing the potential for attracting visitors all year round. Though the main business district of the town was still only three blocks long, development had reached across all the flat spaces and was beginning to creep up the sides of the surrounding mountains. Geologic time outlasts any kind of human time. And the mountains can withstand climate change more easily than any animal or plant life form. In a hundred years or a thousand years, the approaches to Estes Park and Rocky Mountain National Park will still be up from the lower elevations with a last drop to a valley surrounded by mountains. Whether your view is of Twin Sisters or Lumpy Ridge or Ypsilon or our favorite fourteener, Longs Peak, and your family has been here for four generations or you are one of the four million who visited during the last year, remember these words from a song by Cowboy Brad, who we also know as Longs Peak Ranger Brad Fitch, “We live in Paradise.” (This article appeared in a slightly different form in the Rocky Mountain Conservancy newsletter. Are you a member of the Conservancy?) Early Estes Park - A Search for Opportunity

By Sybil Barnes This is a forward I wrote for a section of a 2007 publication featuring the photographs of James Frank. The library still has a couple copies or you might be able to find it on a used book site. “Magic in the Mountains: Estes Park, Colorado.” JJ has had a varied career in Estes as a musician, extraordinary photographer, author, purveyor of First Light postcards, and the original owner with his wife Tamara of the Aspen and Evergreen Gallery. Another major contributor to this book was Paul Firnhaber and several other local “celebrities” wrote introductory forwards to various sections. I’ve made a few minor changes to to the original text: History is how we keep track of our memories. Because few of us can interpret the cry of the hawk or the chitter of a chipmunk or the song of a waterfall, and fewer can even hear the voices of rock or tree, our history is told through human vocabulary. We use our personal experience and recollections of experiences handed down through generations of the people who live in our town to place an order and possible meaning on what may be random events. History is the story of a search for opportunity. The earliest opportunists who came to this area were the people we now identify as PaleoIndians. These nomadic people enjoyed the abundance of wild game and respite from the heat of summer on the high plains. Even then it was a transitory experience. Not many were willing to spend the winters in a place they called “the land of many snows. As civilization and settlers moved westward looking for gold or other means of economic survival, the opportunists tried to figure ways to sell the beauty of the area by offering places to stay for renewal and recreation away from the city. Some of those early settlers were able to stay year-round and leave their names and descendants to guide the town into new ventures and new centuries. Others moved on, leaving only whispers of memory. Estes Park has been discovered and rediscovered, touted as a tourist mecca and vilified as a tourist trap. Estes Park has seen boom and bust, the heartbreak of lives lost through floods and mountaineering accidents, the dreams of scores of entrepreneurs and retirees. Estes Park has been summer home or vacation retreat to millionaires, presidential candidates, company executives, school teachers, artists, rock stars,and hippies, as well as hundreds of thousands of “just plain folks.” Through it all, local residents have drawn solace from the beauty of the surrounding mountains and a pioneering spirit which recognizes that material goods are not the only reward for lives spent. History is a daily experience. And it is a reciprocal one. Your history becomes ours and ours becomes yours. |

"The wild requires that we learn the terrain, nod to all the plants and animals and birds, ford the streams and cross the ridges, and tell a good story when we get back home." ~ Gary Snyder

Categories

All

“Hiking -I don’t like either the word or the thing. People ought to saunter in the mountains - not hike! Do you know the origin of the word ‘saunter?’ It’s a beautiful word. Away back in the Middle Ages people used to go on pilgrimages to the Holy Land, and when people in the villages through which they passed asked where they were going, they would reply, A la sainte terre,’ ‘To the Holy Land.’ And so they became known as sainte-terre-ers or saunterers. Now these mountains are our Holy Land, and we ought to saunter through them reverently, not ‘hike’ through them.” ~ John Muir |

© Copyright 2025 Barefoot Publications, All Rights Reserved