|

Notes from the

Trail |

|

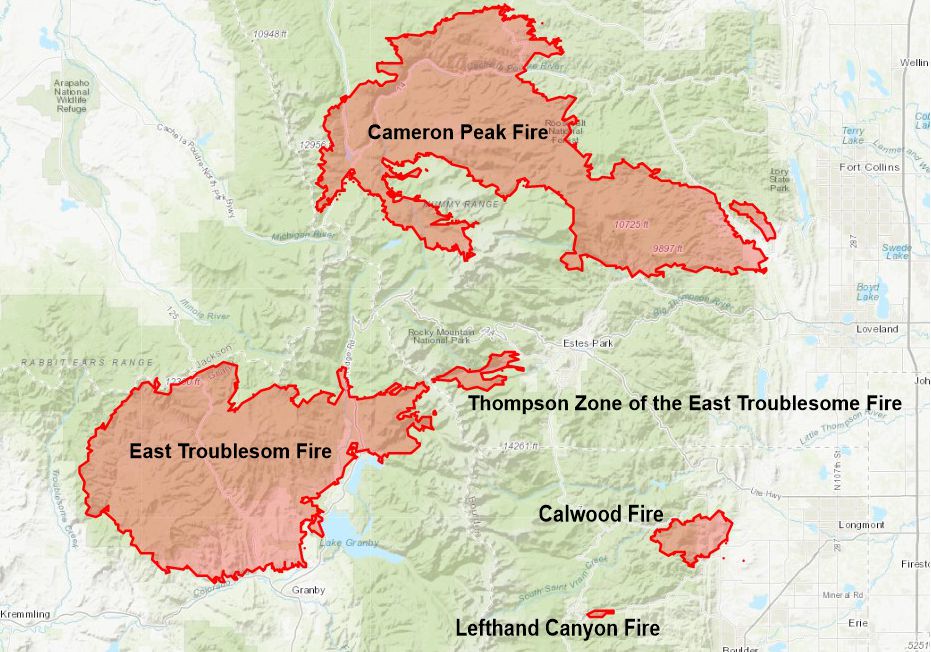

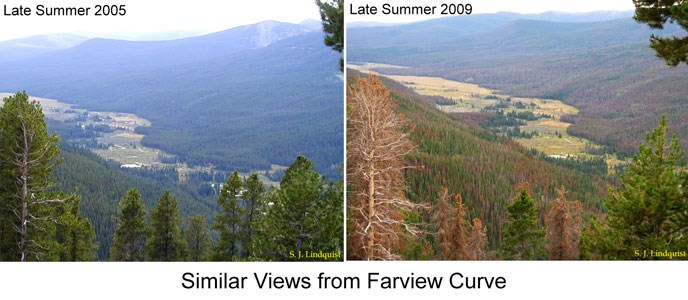

by Barb Boyer Buck The fires surrounding my home in Estes Park caused me to evacuate for a time with my parents; experiencing the mass exodus under midday dark-orange skies with suffocating smoke and ash is something I won’t forget soon. Wildfire is common in the wilderness of the Rocky Mountains but this ongoing situation is unprecedented. The Cameron Peak Fire started in the Arapaho and Roosevelt National Forests, less than 100 miles north of Estes Park, on August 13 when the Pine Gulch Fire, 18 miles north of Grand Junction, had already burned more than 137,000 acres. Pine Gulch was declared the largest wildfire in Colorado’s history until Cameron Peak grew much larger; today, the Cameron Peak Fire has grown to 208,913 acres with 89% containment. This is the equivalent of nearly half of the acreage contained in Boulder County, or more than twice the size of the City of Denver. On August 14, the Williams Fork Fire started 10 miles southwest of Fraser, Colorado, and has burned nearly 15,000 acres with 76% containment. On October 14, the East Troublesome Fire ignited north of Hot Sulphur Springs, west of the Continental Divide. High winds pushed the fire more than 100,000 acres overnight, extending north into the west side of Rocky Mountain National Park. Grand County Sherriff Brett Schroetlin reported this fire growth as “unheard of. This is the worst of the worst of the worst,” he said, in an interview with NPR. Today, the East Troublesome Fire’s footprint is 193,804 acres with 37% containment. On October 17 three miles northwest of Jamestown, the Calwood Fire started. It is currently 76% contained and has consumed more than 10,000 acres. The Lefthand Canyon fire began on October 18, one mile west of Ward and consumed 438 acres of brush and timber before it was 100% contained on Oct. 22. Also on Oct. 22, the East Troublesome Fire experienced another “unheard of” growth, jumping over the Continental Divide in Rocky Mountain National Park, miles of rock and tundra that usually provide a natural fire break. As of today, this spot fire, named the Thompson Zone, has burned 4,346 acres just west of Estes Park, within the boundaries of the national park. Mass evacuations for the Town of Estes Park began on October 22, when the two leading edges of fire from the Cameron Peak and the Thompson Zone/East Troublesome fires had grown to within five miles from the north and west sides of town. The entire Estes Valley was on mandatory evacs by the morning of Saturday, Oct. 24. Highways 36 and 34 were closed to incoming traffic; all of the businesses were closed. Visitors were not welcome. This has never before happened in this tourism-supported community, not even during the 2013, 1,000-year flood. I had been struggling with the smoke that has been ever-present since the Cameron Peak fire began. I have moderate to severe asthma and I quickly invested in air purifiers and visited the doctor for stronger asthma meds and I’ve lost work on bad air-quality days. On Saturday, October 17, I retreated to my parent’s house in Johnstown for a much-needed break from the smoke. I stayed until I had to go back to work in Estes Park on Wednesday, Oct. 21. The very next day, everyone was ordered to evacuate so my cat and I escaped again. I am breathing much, much easier (physically and emotionally) here at my parent’s house but I must return to Estes Park soon, even though the two fires closest to Estes Park are not fully contained. And are still less than 10 miles from my home. For most of us who evacuated from Estes Park, the inclination is to chalk it up to another 2020 debacle. But what set up these perfect firestorms in Colorado started much earlier than this year. It is the culmination of at least 30 years of conditions caused by climate change that are not likely to be fixed by fully containing the last that is fire burning. In an interview with KWGN News on October 23, Colorado’s governor Jared Polis said the wildfires are a combination of “climate change and increased population and utilization of public lands.” Way back in 1996, the Rocky Mountains experienced a cyclical, natural event: the beginning of a pine-beetle infestation. Pine beetles are insidious creatures, boring into the bark of lodgepole pines and slowly killing them. Pine-beetle infestations occur every 30 years or so, but this one was different. This one LASTED for nearly 30 years because of the increasingly warm climate. If it doesn’t get cold enough in the winter, the beetles don’t die and continue their destruction of our forests. A pine tree that has been infested with pine beetles is killed from the inside out. Their needles turn red and eventually fall off; what’s left become “gray ghosts.” Since 2009, these gray ghosts have been more and more prevalent in Rocky Mountain National Park; 95 percent of Colorado’s lodgepole pine forests were killed during this infestation which began to abate in about 2015. These dead, yet standing, trees also create extreme fire danger. Now, add the extended drought Colorado has been experiencing and it becomes clear, it would take only a few years to create the tinderbox that is burning all around my town. According to RMNP’s website, Colorado has been experiencing warmer-than-normal conditions for the past decade. But those conditions still would not have been enough to cause the situation in and around Estes Park right now. The second part of Polis’ statement on the wildfire’ intensity must be taken into consideration. In 2019, Rocky Mountain National Park hosted 4.7 million visitors, most coming through the community of Estes Park. The impact of human utilization of our wilderness is a significant threat, especially when regulations in place to limit harm are ignored. When COVID19 became a significant threat in the spring of this year, it was essential to limit the number of visitors to the national park and Estes Park’s mayor requested it be closed. When the Park reopened in late May, NPS soon implemented a timed-entry reservation system to limit vehicles entering to numbers that were last experienced in 1996. But the reservation system ended on October 12 and even before that, thousands of visitors crowded the Park after 5 p.m. (when a reservation was no longer needed) to watch the elk rut season which began in early September. The National Park, forest service, and Estes Park has had a fire ban since August 15, yet every fire I mentioned above was believed to be caused by human activity except for the Pine Gulch Fire, which was caused by a lightning strike on July 27. The exact causes for all of the other fires are still under investigation but the blame has been laid squarely on humans. Estes Park lifted or downgraded evacuations in town last week but Rocky Mountain National Park and all forest service land surrounding town is closed to all access, except for firefighters. There was a caveat to lifting evacuations orders and to visitors coming back into town: “be prepared to leave at a moment’s notice.” 422 structures have been lost in the East Troublesome Fire to date; it is still unknown how many were lost in the Cameron Peak Fire. Residents in Glen Haven and its surrounding communities were only allowed to return home yesterday. There has been some progress on the containment of the two fire’s edges that directly threaten Estes Park, and visitors are being welcomed back into town. But without the National Park or the Forest Service to recreate in, the only choice is to visit the business establishments in town and COVID19 cases are increasing in all communities in Colorado. Another spell of dry, warm, and windy conditions is predicted for this coming week. To date, the East Troublesome and Cameron Peak fires have burned 29,000 acres of RMNP - the most acreage burned in any fire or combination of fires in the same year since the Park was established more than 100 years ago. If 2020 is teaching us one thing, it’s that we must always pay for our actions. If we don’t take care of our environment, it will take care of itself. No consideration will be given to the fact that humans live here, too. Wildfire serves to clean out the dead growth in our forests, but the extent of wildfire in northern Colorado this year is more than a warning. It signals a significant climate shift and we must all take heed or humans will be another casualty of Nature’s wrath. The following slide show features pictures of the destruction caused in RMNP by the East Troublesome Fire between Oct. 23-25. Photos courtesy of RMNP or Larimer County Sheriff (as noted):

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

"The wild requires that we learn the terrain, nod to all the plants and animals and birds, ford the streams and cross the ridges, and tell a good story when we get back home." ~ Gary Snyder

Categories

All

“Hiking -I don’t like either the word or the thing. People ought to saunter in the mountains - not hike! Do you know the origin of the word ‘saunter?’ It’s a beautiful word. Away back in the Middle Ages people used to go on pilgrimages to the Holy Land, and when people in the villages through which they passed asked where they were going, they would reply, A la sainte terre,’ ‘To the Holy Land.’ And so they became known as sainte-terre-ers or saunterers. Now these mountains are our Holy Land, and we ought to saunter through them reverently, not ‘hike’ through them.” ~ John Muir |

© Copyright 2025 Barefoot Publications, All Rights Reserved