|

Notes from the

Trail |

|

Trailhead: Rock Cut Parking Area Trailhead Elevation: 12,090' Destination Elevation: 12,304' Elevation Gain: 214' Total Roundtrip Miles: 1 mile This summer, I have enjoyed some spectacular hiking into the backcountry areas of Park. Last week, I changed things up a bit and visited a variety of shorter hikes. I began my day by taking a walk on the tundra. I entered the Park at sunrise, the first rays of the sun lighting up the clouds that were forming. By the time I reached Many Parks Curve, the sunrise was putting on quite a show. Note: click on each photo for a larger image. The Tundra Communities trail begins at the Rock Cut pullout on Trail Ridge Road, at an elevation of 12,090', according to a sign posted on one of the restrooms at the parking lot. The 1/2 mile trail is paved and there are not any steps on the trail. The first part of the trail ramps up a ways before leveling off. Of course, there are mountain peak views in every direction. On this day in late August, the sky was fairly overcast. But the sun found a break in the clouds and shone down on the Never Summer Range to the west. Looking to the northwest, the smoke from the Cameron Peak fire was laying low and filling the valleys below. Along the trail, there are interesting rock formations of dark colored schist that originated at the bottom of a sea. The lighter colored granite pushed in as magma. The granite erodes more quickly than the schist and forms forming mushroom shaped rocks. The trail offers the hiker plenty of informative interpretive signs where one can stop and rest while taking in the view. The best time to see the tundra in full bloom is mid summer. But the tundra is rich in autumn colors right now and it's not as crowded with other hikers. The trail dead ends at a high point of rock formations. If you scramble up the rocks, you will find a memorial plaque Roger Toll, the first superintendent for this Park. You can read more on the Park history here and on Trail Ridge Road here.

0 Comments

Story and photos (except the last one) by Barb Boyer Buck Before I go into details of the Cow Creek Trailhead hiking opportunities, there are several things to keep in mind. First, parking is extremely limited and fills up quickly. Roadside parking, or parking in a homeowner's driveway is strictly forbidden. Respectful usage of this trailhead is a must as there are sensitive ecosystems, private land, active researchers, and lots of wildlife also inhabiting the Cow Creek Valley. The McGraw Ranch Road, which is your only access to this trailhead, is a dirt road with mild washboards and can be easily accessed from Devil's Gulch Road, on the north side of Estes Park. If you want to hike this trail, my advice would be to go very early in the morning, or late afternoon. Please remember in the summer months, afternoons often bring thunderstorms and several portions of this hike crosses wide-open meadows. It is not advisable to hike during a thunderstorm, lightening strikes are a very real possibility. If you find yourself wanting to hike this trail at any other time of the day, the best thing to do is have someone drop you off at the trailhead; however, cell phone reception is pretty much non-existent in the area. If you decide on this option, have a plan to meet at a specific time with the understanding that idling cars waiting to pick up delayed hikers are also not permitted. Instruct your driver to check back occasionally if you are not there when you expected to be.

The site of the old McGraw Ranch still has buildings, including one that has been standing since 1871, the original homestead cabin of Harry Farrar. Others were built between 1884-1887, and most of the guest cabins were built between 1935-1936 by Frank and John McGraw (for more history of the ranch's early days, see part one of The Cow Creek Trail, published last week).

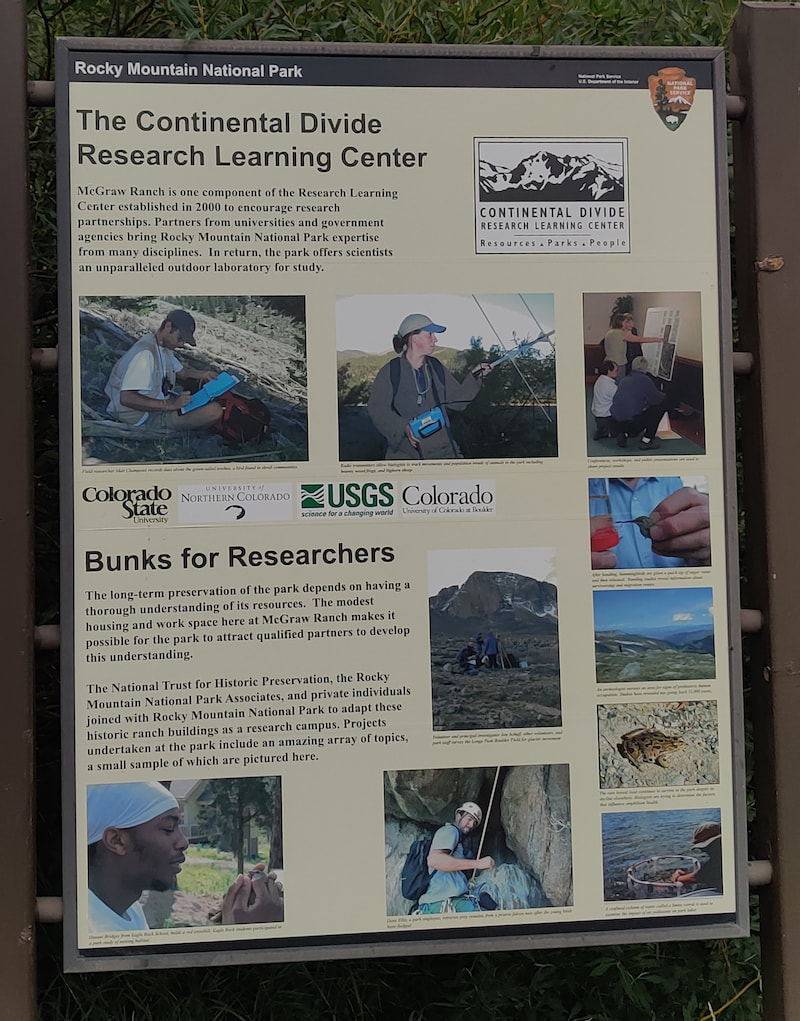

Researchers from Northern Colorado, Colorado State University, and the University of Colorado, along with the United States Geological Survey, now use the surrounding land as an outdoor laboratory. Onsite housing, laboratories, meeting rooms, and dining areas for these individuals are provided by the ranch buildings. The renovation of the buildings started in 1999, the culmination of a partnership between the NTHP and several private citizens to restore the McGraw Ranch buildings to their heyday as a guest ranch, between 1936-1955. The research center opened in 2003, becoming an important site to gather significant data in RMNP; Rocky Mountain National Park is designated as a United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural (UNESCO) international biosphere reserve. From butterflies (there are 142 species confirmed in RMNP) to climate change, these studies provide important, scientifically-gathered information for the entire world. I started my hike at dawn, just before 6 a.m., at the research center. Very soon, the trail has an intersection on the right with the North Boundary Trail which branches up and east. The beginning of the way to Bridal Veil Falls was lit with the sun at my back, glorious coloring the late-summer vegetation and a whitetail deer, grazing along the edge of the trail.

The first part of the hike is a beautiful meadow that climbs a bit before it wanders back to Cow Creek. For most of the hike, you can hear its rushing or trickling waters, something I enjoy very much. It's so relaxing. I needed a bit of calming down because I was anxious about taking this hike by myself, the first one with a distance of more 2 miles I've taken on my own since my back surgery. And there was no one else on the trail that early in the morning. Every rustle in the trees had me looking - this is bear country after all! It's also a hunting ground for mountain lions, although it's very rare to see these creatures anywhere near humans. A bit further down the road comes another trail crossing, this time giving you the option to turn left to hook up with the Lumpy Ridge Trail to visit Balanced Rock and Gem Lake.

Just beyond this spot, there are some steep rocks before the trail picks up again. I didn't dare do this on my own so I guess neither horses nor I would get any further. It was frustrating because ED. (more about ED. next week) told me I was essentially there, but I couldn't chance it. Just a few weeks ago, a woman took a tumbling fall, sustaining serious injuries, above Bridal Veil falls (see more info here: https://www.rockymountaindayhikes.com/rmnp-updates.html) So, I ate some fruit, drank some water and started back. I saw several more people on the trail and I was grateful to be coming back. The sun was higher now, and it was starting to get hot. When I passed through the meadows again, the butterflies were flitting all around me, enjoying the late-August sunshine. It took me about five hours to do six miles roundtrip but remember, I stopped to take many pictures along the way. It was worth it and I needed it. It was the first morning without any smoke haze after two days of good rain. The air was clear, the sky was blue and the morning light was perfect. Happy hiking, everyone! Trailhead: Finch Lake Trailhead Elevation: 8,476' Destination Elevation: Finch Lk-9,925', Pear Lk-10,594', Cony Lk-11,512' Total Roundtrip Miles: Finch Lk-10, Pear Lk-12.4, Cony Lk-18.4 In the south end of Rocky Mountain National Park, as part of the Wild Basin trail system, there are a series of lakes that begin at the Finch Lake trailhead and can give the dayhiker some options on a trail that is not too crowded, but the destinations are all longer hikes.

The trail actually loses some elevation on the last strech to Finch Lake. There are a couple of good rock spots along the eastern shoreline to enjoy this peaceful lake. Finch Lake is a comfortable distance for many dayhikers, and well worth the effort. But for another 2.5 miles, you can also bag Pear Lake. The trail skirts around the north side of Finch Lake, then drops a bit more to a footbridge crossing Cony Creek. There's not too much elevation gain between the two lakes and the trail is pleasant.

This trial is not an official trail of the Park. It is not maintained and there will be some downfall to climb over, for example. If the dayhiker is going to travel here, you will want to plan on a much longer day. After passing the lower of the three Hutcheson Lakes, the trail can be difficult to keep track of, so it's necessary to have an awareness of your surroundings. Having a topographical map and knowing how to read it is also a good idea. This is a pristine alpine environment, so travel carefully. Follow the small trail to reach the Middle Hutcheson Lake. The three Hutcheson Lakes each sit on a self with the lower lake still below treeline, the middle lake in the subalpine and the upper lake right at treeline. Carefully navigate over rock outcrops that look over Middle Hutcheson Lake to reach into the upper basin and Upper Hutcheson Lake. The upper Cony Basin begins to come into full view as the dayhiker approaches Upper Hutcheson Lake. Cony Pass that leads over to the Bluebird Lake basin to the north, can be seen in the distance. Ogalalla Peak can also be seen now. On our day, we decided to travel up to the base of Coney Pass. The pass is steep with lots of loose scree. We reach our high point standing below Ogalalla Peak. The summit, 13,138', is part of the Continental Divide and is a high point marking the south boarder line of the National Park. We then turn our attention east looking at where we have come, and now our return route. We can see Cony Lake below us. Nearby is the prominent Elk Tooth with Meadow Mountain in the far distance. Both of these peaks define the southeast boundary of Rocky Mountain National Park. by Barb Boyer Buck Imagine it's 150 years ago (I do this all the time). Imagine you have made the long trek via horseback to the beautiful mountain valley of Estes Park. At that time, Colorado was a territory of the US and the land was declared "public" by the Homestead Act. Every piece of the valley that is not already developed is open for homesteading. All you have to do is pick out your 160-acre parcel, "improve" the property, and pay a small registration fee. Put yourself in that scene. What is your personal perspective? Are you a child, part of a family looking for a new home? Are you sick of the towns where you live and want some peace and quiet in the Colorado mountains? Do you fancy yourself a wilderness man or woman, fiercely independent and resourceful? You're itching to live off the land and figure things out for yourself. Whatever your perspective, I'm sure you'll agree. The homesteading narrative is romantic and adventurous. Let's say you’re a big game hunting guide and you marvel at the wide-open fields below you as you crest that final hill over Estes Park. It's the late summer of 1871, and the basin looks mostly dry, with only the snake of the Big Thompson River slicing through it (there was no lake back then). You notice the prime spots along the river were already claimed. Now, suppose you ride north in the valley, where the mountains meet the meadows and the elk are plentiful. Finally, you see it. The Cow Creek Valley. The creeks in this valley have been slicing a sliver out of the surrounding Rocky Mountains for millions of years. Upon investigation, you find the valley is more than wide enough to establish a viable homestead and the entire drainage is covered in lush foliage. Imagine you stop to take a drink from the stream. (Don't do that today unless you treat the water!) These are not the exact circumstances that led Henry Farrar to eventually homestead the area in 1871, but it's probably close. These are the kind of things I like to think of when I talk about hikes in historic sites within Rocky Mountain National Park but when I was a kid, I hated history. I struggled in class to remember dates, names, events. I only fell in love with history while I earned a BA in Anthropology. Suddenly, I found context in past events. I studied possible motivations for historical figures. I found similarities between myself and everyone who came before me. I can imagine myself into the mindset of someone in Estes Park, 150 years ago. In the case of the Cow Creek Valley, I can imagine the stirring excitement of the situation, being given just enough help through the Homestead Act to get myself started in something entirely my own. In reality, Estes Park had long been the hunting grounds for native Americans, a summer stop on their nomadic routes. Just because a place had never been permanently settled, doesn't mean anyone should claim it. It had been a public, shared, space for ten thousand years before the homesteaders arrived. Several buildings near the original homestead near Cow Creek were finished in 1887 after the property was developed with its sale in 1884. The barn, the lodge, the bunkhouse, and two additional cabins started this valley along another journey. It provided water for cows and the family that lived there. I imagine an idyllic scene, exactly how you'd imagine what a Little-House-on-the-Prairie homestead would be like here, in its perfect riparian ecosystem. Bounteous and cozy. I'm an environmentalist, so I understand the damage human development has affected on our ecosystem, but the feeling of adventure, possibility, and excitement is intoxicating. John and Irene McGraw, grandparents of the surviving McGraw lineage, bought the ranch outright in 1909. John set it up so there could never be any debt on it. There was no way any of his kin was going to gamble with the family home by using it as leverage in other concerns. This pioneer tradition of establishing family ranches can be found in nearly every rural town, including those close to a National Park. Frank and his brother John, sons of the senior McGraws, turned the place into a dude ranch in 1936 by building additional cabins, eager to get in on the action so many in the area had at the time by taking in lodgers.

The McGraw family was the backbone of the operation and was living onsite, but everyone had to move to a hotel in Estes Park to make room for the Landon family and his campaign. Secret service personnel were housed in the bunkhouse, the Landon family lived in the lodge. The McGraws would return to the ranch every day to cook for everyone and take them on horse rides. One of the most popular rides was to Bridal Veil Falls. Eventually, this well-trodden path became the Cow Creek Trail.

After Landon's visit, the McGraw Ranch was on the map and the family, eventually including Frank's wife and five daughters, were essential to its success during its 52 years of operation as a guest ranch. In 1988, The McGraw Ranch was sold to the National Park Service and became part of Rocky Mountain National Park. Go to Part Two of The Cow Creek Trail next week when I will describe trail specifics, more historical anecdotes, and explain what the McGraw Ranch buildings are being used for today. Trailhead: Lawn Lake Trailhead Elevation: 8,540' Destination Elevation: 10,559' Total Elevation Gain: 2,180' Total Roundtrip Miles: 9.4 The trail to Ypsilon Lake is a quiet trail traveling up to a fine alpine lake. This can be a casual dayhike if not in a rush. However, with careful route finding, there can be adventure opportunity by trekking beyond the lake. The hike begins at the Lawn Lake trailhead at the west end of Horseshoe Park. The initial trail rises off the broad valley floor on the northern side with occasional views of Endovalley and Sundance Peak.

The trail then rises quickly again and maintains a steady uphill pace as it meanders through lodgepole pine. Eventually, there's a welcoming view of Ypsilon Mountain through the trees. From here, the trail drops to the lake. When the trail reaches Ypsilon Lake, the views are to the east. There is a non-established 'fisherman's trail' that skirts along the south shore of the lake and a little careful navigation along the eastern shore brings one around to views of Mt Chiquita. The surrounding terrain blocks the view of Ypsilon Mt from the lake. At the inlet to Ypsilon Lake, there a small footbridge and a path that leads to a beautiful waterfall, a must see if traveling to the lake. My hiking partner and I decided to further. Again, with careful navigation up steep terrain, an unmaintained trail leads up to the spectacular Spectacle Lakes, surrounded by rocky terrain, at the very foot of Ypsilon Mountain, now on full display. After having a break, and considering working our way to the upper lake, with still plenty of summer sun, we opted for a different route. The Spectacle Lakes are embraced by two long named ridges that come off the summit of Ypsilon Mtn like two arms, popular in the alpine climbing world, the Donner Ridge on the south and the Blitzen Ridge to the north. After careful examination, we picked a route on the far east end of Blitzen Ridge to traverse into the Fay Lakes region.

We were treated by a very brief visit by this little critter, either an ermine or a long-tailed weasel. It was hard to get a good look at it because it moved around so quick, and then disappeared. There are numerous small waterfalls between the upper and middle Fay Lakes. Blitzen Ridge of Ypsilon Mtn is in the background. We navigated quickly down to the Middle Fay Lake and then picked up a faint trail marked by rock cairns back to Ypsilon Lake. Trailhead: Chapin Pass (on Old Fall River Road) Trailhead Elevation: 11,020' Destination Elevation: 13,514' Total Elevation Gain: 3,134' Total Roundtrip Miles: 8.5 Scenic mountain peaks are the hallmark of Rocky Mountain National Park. But reaching the summit of many peaks can be challenging if not impossible for the dayhiker. However, with a little uphill effort, the Chapin, Chiquita, & Ypsilon trail off of the Old Fall River Road affords three summits within easy reach. As we begin our early morning hike, a Clark's Nutcracker calls up the sun. We ascend into the alpine with the trail leading us into the morning sunlight. We are stopped by a White-tailed Ptarmigan standing watch along the trail, then suddenly notice five little chicks crossing the trail. While we watch them wander off, we look back and see Lava Cliffs off of Trail Ridge Road in the distance. It would be easy to walk right by the side trial that leads up Mount Chapin. From the summit of this lowest of the three peaks (12,454'), we could see Horseshoe Park and Deer Mountain to the east. We backtrack back down to the main trail and continue up Mount Chiquita. Looking across to Mt Chapin, we can see tiny hikers on the summit. The trail up Mount Chiquita can be a little difficult to keep track of, but there are rock cairns marking the way up. This is a steep and sustained part of the hike requiring numerous stops to catch our breath and take in the surroundings. We look down on Lake Chiquita from the summit of Mount Chiquita (13,069') and take a much needed snack break while enjoying the 360 degree views. To the novice geologist, these exposed rocks on the summit appear to be sedimentary layers, perhaps from an old ocean bottom, that was uplifted over the millennium. We enjoy the patches of alpine wildflowers bringing color to the otherwise sparse landscape while we climb up the last of the three peak series, Ypsilon Mountain (13,514'). It felt like a lot of effort to drop elevation off of Mt Chiquita and then climb back up Ypsilon Mtn. But gazing down on the Spectacle Lakes made the effort worth it. After our return decent off of Ypsilon Mtn, we skirt below Mt Chiquita. There may have been a trail crossing here, but we didn't see it and we carefully made our way back, rock hopping where we could, before reconnecting with the trail. Journeying back on the trail across the tundra, and feeling satisfied with our accomplishment, we marveled at the surrounding rocky mountain vistas. After finishing our drive up Old Fall River Road, we stop off at the Lava Cliffs pull over on Trail Ridge Road and gazed upon the three peaks we had just climbed. What a fantastic way to spend our morning!

The trail passes by and in front of numerous mountain peaks and you can use numerous rest stops with a map figuring out what all the names of the peaks are. At about the halfway mark, the trail begins its drop into the Tonahutu Creek drainage and back into the trees.

|

"The wild requires that we learn the terrain, nod to all the plants and animals and birds, ford the streams and cross the ridges, and tell a good story when we get back home." ~ Gary Snyder

Categories

All

“Hiking -I don’t like either the word or the thing. People ought to saunter in the mountains - not hike! Do you know the origin of the word ‘saunter?’ It’s a beautiful word. Away back in the Middle Ages people used to go on pilgrimages to the Holy Land, and when people in the villages through which they passed asked where they were going, they would reply, A la sainte terre,’ ‘To the Holy Land.’ And so they became known as sainte-terre-ers or saunterers. Now these mountains are our Holy Land, and we ought to saunter through them reverently, not ‘hike’ through them.” ~ John Muir |

© Copyright 2025 Barefoot Publications, All Rights Reserved