|

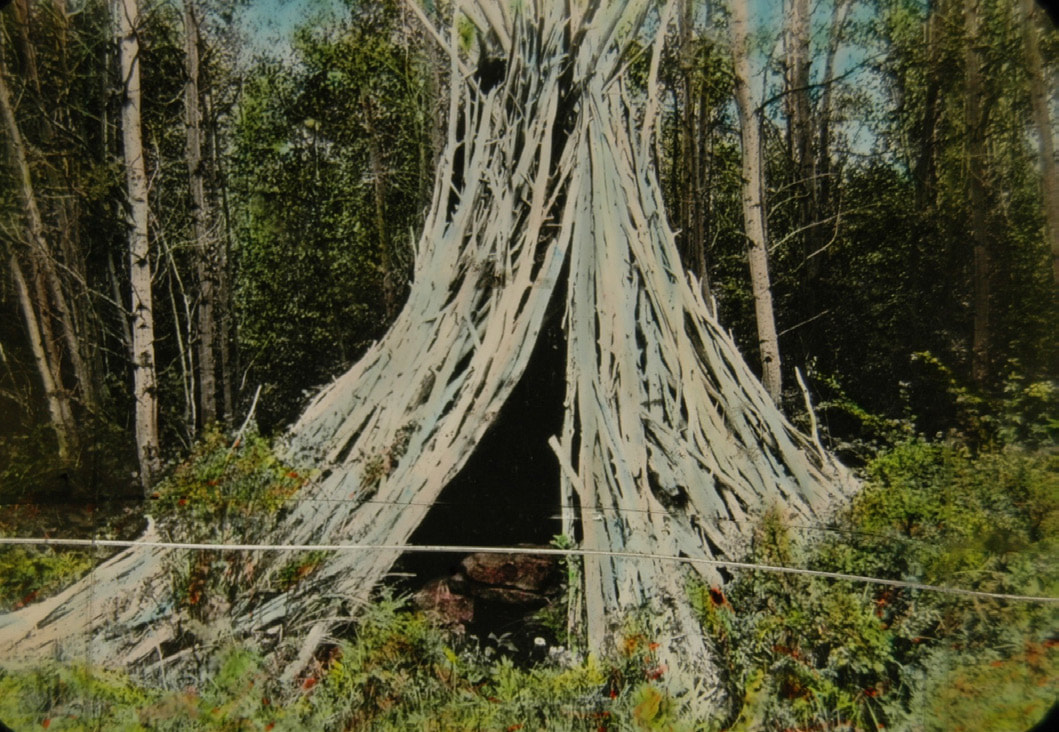

by Cindy Elkins How do we begin to accept our responsibility as travelers on this planet when our existence is temporary? Discovering what came before and accepting that there will be many future generations once I am gone, makes me ponder why it is so important to “Preserve and Protect.” Learning about past inhabitants and establishments while imagining the flying cars of the future, I appreciate my simplistic understanding of what it would have been like 10,000 years ago in the high country of what is now RMNP. Thinking about surviving the elements, hunting for bison or mammoth, foraging for food and being in a landscape recently carved by glaciers, I appreciate that my interactions with Rocky are purely recreational. Imagine seeing the base of Lumpy Ridge covered in the skulls of bison after a great hunt, or witnessing the competition between Arapahoe and Ute nations for hunting rights next time you are hiking the trails. This article is an attempt to give a glimpse of who was here before the Euro-American settlers came west. According to https://www.nps.gov/romo/learn/historyculture/tim e_line_of_historic_events.htm : “The…Clovis Paleoindian hunters entered the park as the glaciers retreated around 10,000 BC… and from 6000 BC to around 150 AD Archaic hunter-gatherers occupied areas of the park as seasonal hunters in the spring and summer months. These are the ancestors to many of the tribes in the western United States including the Ute, Comanche, Goshiute and Shoshone... Sometime around 1200 -1300 AD members of the Ute Nation enter into Colorado's North Park and Middle Park as well as areas of Rocky Mountain National Park… It is believed that around 1500 AD the Apache are in the high country of what is now the Rocky Mountain National Park... Members of the Arapaho Nation are believed to arrive in Rocky early in the 1800's. Shortly thereafter in 1820, the Stephen A. Long Expedition comes along and names Long's Peak as his own. "They are reported as the first non-Indians to see the area.” Just over 200 years ago the Euro-American's arrived to an area that had supported and provided for our human ancestors for over 11,000 years. That is something to ponder. In my opinion, we have an obligation to respect those who were here prior and those who will come through after we are gone. There have been several discoveries within the boundaries of Rocky Mountain National Park. Remnants of wooden shelters called wickiups date back 300 years. Traces of ancient hunts can be found in Rocky. Low rock walls, still in place today, were once used to guide game to their death. Once a happy hunting ground for nomadic tribes, now a thriving artist, tourist and outdoor-adventure mecca, RMNP has had many faces. A rock outcropping near Beaver Meadows designates where a fierce battle was once fought. The magnificent Ute Trail which is named for some of the original people who used it, crosses through all three elevation life zones that are in Rocky: alpine tundra (11,000 ft and up), subalpine zone (9k-11k), montane zone (5600-9500 ft). This hike was one of the main foot paths to cross the continental divide. It can be started up on Trail Ridge and is a well-marked hike down, or go up it. Nestled on the northwestern edge of Estes Park, 8310 feet or 2533 meters above sea level, Old Man Mountain is a granite silhouette of an elder looking west. A magnificently powerful mountain that is protected, so please obey the signs. There are at least five locations that are known ritual sites up on Old Man. These are considered important archeological places as well as vision quest sites. Old Man Mountain is not public. It is considered a sacred site of Colorado and is mostly private land with no clear trail to summit. Remember that honoring traditions and respecting cultures builds community. We ask that anyone in our hiking community tread lightly when in the Park and all surrounding areas. So, who were the original inhabitants like that made their way through the west and flourished around Northern Colorado? Why did Joel Estes report that he and his family never saw nonwhite folks when they arrived to build their cattle ranch 1858? Piecing together history that is mostly oral or concluded by the discovery of artifacts, emphasizes the importance of the RMNP policy of leaving anything you find exactly where you found it. Report all finds or possible discoveries to the rangers, and take a selfie with it for prosperity sake! Clues come in all shapes and sizes. The image of arrowheads shows the similar and different tools that were hand made by chipping at stone. A practice that is found worldwide. Like the mammoth, buffalo and original elk herds, the last of the Native Americans were driven out. The Arapaho, Ute, Apache, all tribes who crossed through the area are part of the history; part of what makes this place so special. As a traveler, local or tourist, next time you are up in the Park or just dreaming about it, listen closely. The wild winds of Northern Colorado may just whisper a clue from the past that fuels your imagination. You may find yourself as you go hiking across peaks or through marshy fields of braided creeks. You maybe wondering what it was like before and knowing that if we do our part, there will always be the special places. Keep Rocky wild and free. References: https://www.nps.gov/romo/learn/historyculture/time _line_of_historic_events.htm https://www.nps.gov/romo/learn/education/upload/ Cultural-History-Of-RMNP-Teacher-Guide-Final.pdf https://www.eptrail.com/2014/10/24/snowbirds-not- new-to-the-estes-valley/ This article is included in the November 2021 edition of HIKE ROCKY magazine.  Born in the mountains of West Virginia, Cindy Elkins has called Colorado home since 1981. As a professional artist and teacher, hiking and the outdoors provide inspiration and keep her active.

0 Comments

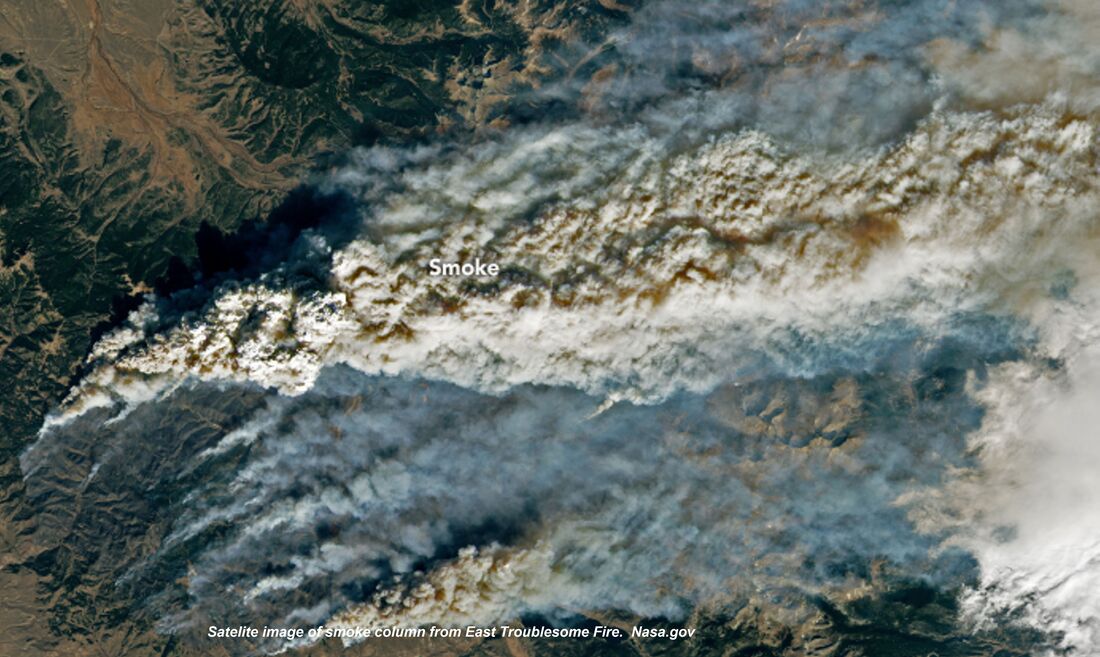

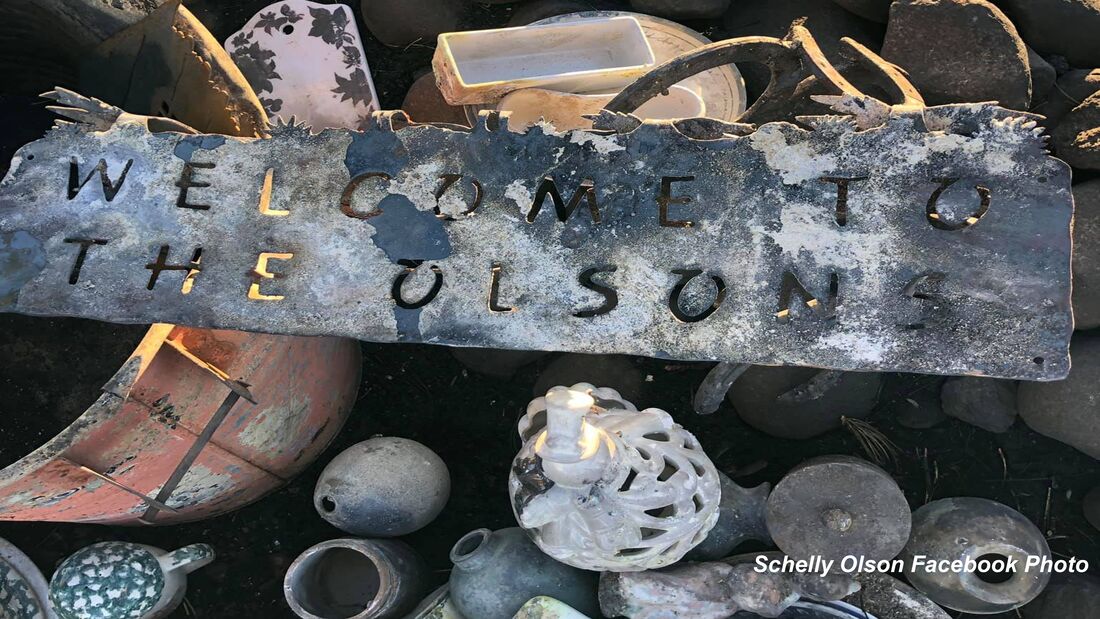

story by Dave Rusk photos by Murray Selleck “What do ya think?” We stood before some fallen logs strewn across the trail that required climbing over in order to go forward. “I don't see why not.” The sign had warned us that two miles into our 5.3-mile hike to Timber Lake on the west side of Rocky Mountain National Park, there would be an active landslide with possible moving soil and falling trees. Now, here we were at that point. “I don't know. When I was here before, they had diverted the trail up and around.” That had been seven years ago and I was surprised that this was still an ongoing thing. But the sign did say to proceed, “at your own risk.” “Well, let's go see what it's like. Probably not that bad.” We stepped carefully onto the fallen logs. They were covered with a bit of snow that was melting and making them slippery. But we moved forward to where we could get a better look. A gouge down the hillside of mud and fallen trees appeared before us. The Park had cut a few trees and we followed a makeshift path that dropped steeply down into the ravine. The path slid narrowly between some cut logs going one way and a fallen tree going the other. Then we ducked under that tree. There was a rivulet of water flowing down the ravine and I imagined during spring melt, this hillside might become very fluid and unstable. But right now, at the end of the season, the mud slide seemed dry and solid. So, a short scamper up out of the ravine and that was it. “Well that wasn't much of a problem.” “Yeah, it was a lot shorter than I thought it would be.” I had met my friend, Murray, in Grand Lake the evening before, our hike having been delayed a day due to a first-of-the-season snowfall that had temporarily closed Trail Ridge Road. Weather can always be a factor, making planning for an autumn hike difficult, although it ended up being a beautiful early fall day. While a number of trails on the west side of Rocky have been damaged by the massive Troublesome Creek fire the previous October, with some trails still closed, the fire did not reach the Timber Lake trail, which starts out at the base to Trail Ridge Road across from the Colorado River Trailhead. We had stayed the night before at a friend's cabin in Grand Lake, grabbing some take out at White Buffalo Pizza. There was a pretty good frost the next morning on the windshield, so we didn't rush out the door. By the time we got to the trailhead, at about 9,000 feet, the sun was warming the frosty grass in the meadows. We hopped out the truck and took a look around. Golden aspens accented a Colorado blue sky with a decent dusting of snow gracing the peaks across the valley. Despite the unexpected one day delay, it looked like we were going to have a gorgeous hike and we were excited to hit the trail. As we started our frosty hike, we wondered how deep the snow might get as we gained elevation with Timber Lake resting at 11,000 feet. The trail starts off easy enough, traversing around the lower west side of Jackstraw Mountain, crossing over Phantom and Beaver Creek, and then begins a steady climb going around the south side of Jackstraw and into the Timber Creek drainage. But while some sections of the 2,000-foot elevation gain got me huffing, the trail is mixed with more gradual stretches too. Once past the brief but tricky landslide area, the trail continues its steady but gradual rise through subalpine forest, eventually bumping into Timber Creek. At one point, an open meadow comes into view and I am reminded of spending time here one early August photographing and tip-toeing around a large patch of Elephant's Head wildflowers. It was a beautiful patch. But the meadow was mostly dry and dormant now, waiting for a return to winters nourishment. The trail follows Timber Creek closer here before breaking into a clearing at just under 11,000 feet, with good vistas of the Continental Divide to the north, where a trail to Mount Ida travels above tree line. At this point, it seems like you must be very close to Timber Lake, and you are except that the trail takes an unexpected turn to the east through more forested terrain, rising to just over 11,000ft before finally coming onto the lake right at tree line. There was maybe an inch or two of snow around the lake and the dusting on surrounding ridges looked splendid. I've been here as early as mid-June when the lake was still thawing out from the deep winter snow. I've also been here in mid-summer with terrific wildflowers surrounding the lake. And now the end of September with first snow. They've all been great hikes. We find ourselves a sunny lakeside rock and pull out our snacks, taking in the views and the sunshine. There are smaller ponds farther on nearby that can be explored and some folks like to climb up the ridge at the far end of the lake to ascend Mount Ida. On this day though, we just take it easy and enjoy the peaceful solitude of this end of summer beauty before our return.  Dave Rusk has been sauntering and taking photographs through Rocky Mountain National Park for decades. He is the author publisher of Rocky Mountain Day Hikes, a book of 24 hikes in Rocky, and the website of the same name. He is the publisher of HIKE ROCKY Magazine and an important content contributor to all of these endeavors. Lessons learned from Colorado's biggest, wildest fires (part 3)Note: the following story was included in the February 2021 edition of HIKE ROCKY magazine and is being reprinted to accompany the new documentary, FIRESTORMS by Barb Boyer Buck “Hope is not a strategy,” said David Wolf, fire chief for Estes Valley Fire Protection District, about the realization the Cameron Peak Fire, which started north of the Estes Valley on August 13, 2020, could burn straight toward his jurisdiction. “There was nothing but fuel” between the fire and Glen Haven after it jumped Highway 14, so Wolf started preparing for if it came this way. “The day (the Cameron Peak fire) started, we were coming home from Grand Lake, driving through the Kawuneeche Valley and I saw a plume on the horizon,” recalled Kevin Zagorda, chief of the Glen Haven Area Volunteer Fire Department. “I turned to my wife and said, that's fire.” Zagorda thought it may be coming from somewhere in the Never Summer Range, “but by the time we got up Trail Ridge Road and got to Medicine Bow curve, you could clearly see where it was coming from, and that it was big.” Rocky Mountain National Park's fire management officer, Mike Lewelling, started a response in conjunction with the National Forest Service right away. “At first, we thought it was in the Park,” he remembered. The northwest section of RMNP is some of the most remote wilderness in RMNP's boundaries. Lewelling started working with the forest service to pinpoint the fire's exact location, which turned out to be 15 miles southwest of Red Feather Lakes, less than 80 miles north of the communities around Glen Haven, the Estes Valley, and the northern border of RMNP. At first, the fire wasn't moving toward the Park, Lewelling said, so he and his team concentrated on preparing for if it did. “That first week, we were brought into the Forest Service planning efforts,” he said. He and the incident commander for the section of fire that was closest to RMNP flew over the fire to assess. “I wasn't too concerned until I flew over Chapin Pass, and realized if the fire went up and over, that's where our Willow Park cabin is (along Old Fall River Road), and that's the Fall River drainage – which goes right into Estes Park.” Lewelling said they identified a few places along Fall River where they could “maybe make a stand,” but it didn't look like any line they could establish would hold. So, efforts shifted to developing evacuation plans. Even though it hadn't yet reached the Park's boundaries, on August 18 2020, some sections of northwest RMNP were closed. A week later, the Cameron Peak fire made its “second push,” Lewelling said, “and it came into the Park pretty fast.” Due to the inaccessibility of that section of the Park, it was very difficult to pinpoint the exact location, but it was clear the fire was within RMNP's borders. But then, a very early snowstorm hit on September 8-9, one of the earliest snows with accumulation recorded since the late 1800s. This stalled the fire's progression. Over the next few months, the Cameron Peak Fire “didn't want to move south into upper Chapin Creek, the area we were worried about” Lewelling said. They used helicopters to sprinkle the leading edge with retardant, but that doesn't really do much unless ground crews could go in to follow it up, he explained. All they could do was hope the fire didn't move south. More dry and windy weather followed the early- September snowfall and crews continued to work the Cameron Peak fire over the next six weeks as it burned toward communities northheast of the Park, including Glen Haven. “We had become a Fire Wise community in July,” GHAVFD Chief Zagorda said; as soon as the fire started, the communities in the Glen Haven area began to prepare. “A lot of the property owners had done significant mitigation work before the fire even began, which was a big plus for us,” he said. “We also had updated our Community Wildfire Protection Plan earlier that year.” A volunteer organization, Team Rubicon, contacted Zagorda about doing mitigation work in the Glen Haven area earlier in 2020. Team Rubicon is a veteran's organization that provides humanitarian and recovery aid to communities all over the country. “We took a look at our vulnerabilities and knew we were vulnerable in any of the drainages (ie, Miller Fort, North Fork, West Creek), so we knew we wanted to do some thinning of trees and other mitigation work toward the edge of developed areas.” An area in the North Fork drainage was completed and an area around the Retreat was partially completed, Zagorda said. “And then, a couple of weeks before the fire, Larimer County contacted me. Their fuels crew wanted to come up and do some work in Glen Haven.” They were going to finish the area around the Retreat in September. But by then, everyone was engaged in actively fighting this fire, which ended up burning 208,913 acres in Larimer and Jackson counties, making it the largest wildfire in Colorado's history. On October 14, the Cameron Peak fire made a “pretty big run on a red-flag day, I think it was a 12-mile run, that fire came down Panic Pass and down the Miller Fork drainage and got into the Retreat, just outside the developed areas.” But where Team Rubicon did fuel reduction, “it took a lot of the punch out of the fire,” Zagorda said. As a result, and with a little help from the weather which had turned cold again, his team was able to battle the fire directly in those areas, keeping it away from homes. This effort was bolstered a lot by the mitigation work the property owners had done, earlier that year. “I sat up there at the lookout point and watched the fire coming down the hill. It was very smoky, you couldn't see very much, but I was convinced a lot of those homes were going to be lost. As the smoke began to clear, you could see the fire come down and burn around the houses, because of the mitigation work the property owners had done,” Zagorda reported. Another thing that helped prepare for this fire was a community workshop on how to develop an evacuation plan, held by the department in August. GHAVFD and EVFPD helped Larimer County with evacuations and then got quickly to work on “rapid structure protection,” Zagorda explained. In about five minutes at each property, the crew worked to remove all combustibles away from the house did some quick chainsaw work on vegetation, and sprayed a little fire- fighting foam. “And then we had to back out and wait for the weather to cooperate before we could fight the fire directly.” The community of Glen Haven lost one home and three second homes. Several building and outbuildings were lost as well. No human or animal lives were lost in this area. The fire came within one-third of mile from Zagorda's house; he and his wife were evacuated for three weeks during which they moved seven times. Interagency cooperation and joint efforts are extremely important when fighting wildland fire, and with training efforts. Chief Wolf from the Estes Valley district, led a strike-force commander training session earlier that year which Zagorda credited as being very valuable during this fire. “Estes Valley and Glen Haven have a very good working relationship, we are mutual aid partners and we train together,” he said. Type I incident command teams arrive at big, dangerous fires – they are made up from crews from all over the country and serve about 2-3 weeks before another team is deployed. When they arrived at Glen Haven, they helped with setting up sprinkler systems for structure protection, bringing that equipment from the Red Feather Lakes area. Lewelling's crew began efforts in the Glen Haven area at about this time, too – the National Park was now on fire near its northeastern border, burning around Signal Mountain before back-burning about 300 acres into RMNP land and threatening the North Fork ranger cabin. “Make friends before you need them.” Lewelling got this piece of advice at the beginning of his career and with firefighting, it's absolutely essential. Wildfire doesn't respect jurisdiction lines and interagency cooperation and communication is key to successful fire management. The same day the Cameron Peak fire made its epic run toward the communities surrounding Glen Haven, the East Troublesome fire began on the west side of the Continental Divide. Along with serving as the assistant chief of the Grand County Fire Protection District 1, Schelly Olson is a public information officer for for fire incident teams, going out on fires all over the country. Many times, she is not necessarily working local fires; in fact, that summer she had been on a couple of fires in Arizona and then the Williams Fork Fire, 10 miles southwest of Fraser. “I had been on the Williams Fork fire for almost 50 days,” Olson said. She and a friend from Eagle County, also a PIO, needed some rest so they bought plane tickets to take a short vacation in Florida. The forest service called on October 14 to see if Olson could be PIO for the East Troublesome fire, but she declined because she had already booked the tickets. “I felt tremendous guilt because here was a fire in my county, and I'm leaving. “I did not know what (the East Troublesome fire) was going to do,” she said. She was still in Florida when the fire blew up the following Wednesday. It had been a tough fire season for those in Grand County, reported the Grand Fire Protections District 1 chief, Brad White, with multiple fires in the region. “Most of us lived under smoke clouds the entire summer,” White reported. Centrally located near Granby, his crew is often called out for interagency work as well. But when the East Troublesome fire started, White and seven other members of his crew were on quarantine for a known exposure to someone with an active COVID infection. The chief was working from home when he got a call from the Grand County sheriff, wanting to put part of White's district under a pre-evacuation order– the fire had burned 3,800 acres that first day. “Well, I said that's fine but I want to get a look at this fire myself.” After he assessed what the fire was doing, he contacted the sheriff and advised evacuation zones needed to be established all the way to Highway 34. There are a total of 5 fire protection districts that serve Grand County which is 1,870 square miles in area. They all perform mutual aid within the county, and with federal land management agencies - the forest service and national park service. The incident command team that had been dispatched to the Williams Fork fire stepped up as well. “October is a bad time of year to try to get federal resources so the (incident command) team was already thin. But not only did they agree to take on this new fire, they agreed to stay an additional week,” White said. Over the next couple of days, the fire grew from near Kremmling to the Hot Sulphur Springs area. On October 19, the wind started picking up again. “It was a pretty active few days, with air tankers dropping slurry,” White remembered. On the morning of the 21st, crews predicted the fire might cross Highway 125, where a few homes and ranches were located, so all those people were evacuated. “We felt pretty good because the fire was moving rapidly, but it was moving northeast toward Gravel Mountain,” away from more populated areas in an area where the fire could be boxed in. The mountain area mutual aid group (MAMA), which had been formed several years prior with 10 other Colorado counties, had been contact to help expedite resources and help with the evacuation of the Trail Creek subdivision, located off County Road 4 west of Lake Granby. But around 7 p.m. on the evening of the 21st, White realized something different was happening. “It got really dark up there,” he said, “the smoke column settled down and the winds really picked up.” From about 7-8:30 pm MAMA was involved in evacuations throughout the district and then started to try to protect structures. Similar to what Chief Zagorda and his crews were doing in Glen Haven, these crew members tried to save homes by removing combustibles from around the homes that were threatened. “At one point, I figured out the fire had traveled 17 miles in 90 minutes,” White said. “That's not the kind of fire you put fire fighters in front of.” In Grand County, “we lost 366 homes and I'll bet we lost 300 of them in that first big blow-up.” Meanwhile, back in Florida, Olson's phone was blowing up with calls from people asking where she was, how they should evacuate, etc. She was also receiving evacuation notifications for her home. “My husband was home alone and he wasn't signed up for emergency notifications so I relayed them to him,” she said. Because the fire blew up so quickly, he had about 10 minutes between the pre-evac notice and mandatory evacuation orders. “He was not able to pack up anything, only get himself, some clothes and our dog Rambo out,” she recalled. “I found out about the house at 2 o-clock in the morning, “We had a very large heavy-timber solid log home – the logs were 24 inches in diameter. Very hard to burn.” But nevertheless, the house burned to the ground, a complete loss. Olson's husband, Jeff, reported he could see the orange glow, feel the heat and extreme wind, and that it sounded like a freight train coming toward him, just prior to his evacuation. “Our house sat on the top of a hill and right behind us was a golf course. In front of us was the road, and on the other side of the road was marshy swamp land and then the Winding River Ranch. The ranch was a huge open space, no trees, only grass.” A few of the homeowners including the Olsons, had removed trees closest to their structures for a buffer, “but obviously, none of us had enough of a buffer.” The surrounding terrain, which logically should have provided fire breaks, didn't help either. Olson explained why: “The wind blew giant embers ahead of the fire. Everything was pre-heated because of that hot wind. Fuel can start combusting, even without that direct- flame impingement. The embers just showered down and landed on everything,” Olson said. In other cases, windows were blown out and embers got inside homes, burning them from the inside out. “The engine block that was in the car in our garage just melted onto the concrete floor, creating what looked like a sculpture,” she said. All of her jewelry was pulverized by the extreme heat. Meanwhile, on the east side of the Divide, Lewelling was discussing evacuation plans for Park personnel with the district ranger in the Kawuneeche Valley. “When she told me the fire was at Sloopy's – the burger joint just south of the Park - it really hit home.” Park personnel stationed on the west side of Rocky evacuated over Trail Ridge Road and reached the emergency command center at midnight– where Lewelling, Wolf, and many other officials were coordinating efforts. “A big part of this story is what you see in people's eyes,” Lewelling said. “We're all professionals with many years of experience, but you could see it in people's eyes – this was different. This was a different event.” Lewelling thought that was all that was going to happen for the night. “Certainly, it wasn't going to cross the Continental Divide,” he thought. But first thing in the morning of the 22nd, he got a call from the National Weather Service, telling him weather satellites detected a heat signature on the east side of the Divide. “From how much the wind could blow the smoke column, that signal could just be embers in the smoke column. It doesn't mean there is fire on the ground,” Chief Wolf said when he first heard about the weather satellite's detection. Mid-morning, it became clear the fire had indeed jumped the Divide and was working its way to the Fern Lake burn scar. Around noon that day, the emergency management team started working on an evacuation plan for the Highway 66 corridor. It was still not clear how far the down the fire had gotten down into the east side of the Park because of the heavy smoke that was billowing out in front of it. By the time it was confirmed, the fire had reached Mount Wuh and had already blown past one of the evacuation triggers, Wolf said. The triggers were set by a joint emergency management team in 2017, which predicted what would happen if a fire which started in Rocky got into one of the drainages leading into the community of Estes Park. These models predicted such a fire under worst-case scenarios would burn through the town in four hours. The current situation was worse than any scenario imagined. It was time to act quickly. By 2 p.m., for the first time in history, the entire Estes Valley was under a voluntary evacuation order; by Saturday, October 24, the order was upgraded to mandatory for everyone in the valley. “Since law enforcement was handling the evacuations, we were able to focus on other priorities, such as protecting our communications, the hospital, and long-term care facilities, knowing that they would need more time for evacuations,” Wolf explained. Another concern was the water supply. “We knew that the number of resources we had were not going to be enough for the fire fight we were expecting,” Wolf said. Emergency management called out for more resources and were rewarded with a lot of assistance from communities along the Front Range. Saturday night, the local crews could finally have a night off. But at 2 in the morning Sunday, they got another call – a structure fire, unrelated to the wildfires, burned down a home. Sunday morning, everyone was happy to wake up to snow, Wolf said. But now that electricity and gas had been turned off to all the valley's structures, there was a danger of freezing pipes. So, crews helped to winterize homes, and get pilot lights re-lit. The planning that occurred in 2017, organized by Lewelling and Wolf and with the input of many other emergency management personnel was extremely useful during this event, Wolf said. “We thought we would be fighting fire on Elkhorn Avenue by the end of the day,” Wolf said. Luckily, that wasn't the case. “Overall, when we look at what happened with the Cameron Peak and East Troublesome fires, I would say that we were very successful. We were also very lucky,” Wolf said. Efficiency in interagency coordination and cooperation, planning for worst-case scenarios, and effective mobilization of resources was a lesson already learned by Zagorda, Wolf, and Lewelling, thankfully. But one thing that they hadn't thought of is where they would get food- they had just evacuated everyone, including the grocery stores and restaurants. For Chief Zagorda, the fuels mitigation work conducted by volunteers and homeowners saved quite a few homes. Asst. Chief Olson said that one of the lessons learned was to install reflective house numbering, so addresses can be found quickly in an emergency. “Grand County is ground zero for the pine beetle infestation,” which killed 95% of the lodgepole forests, she said. “Fuels mitigation is a big part of this.” Prescribed fires and fuel reduction in Rocky was instrumental in keeping the fire west of the Estes Valley, several of the fire management professionals noted.

All of the fire agencies who were approached for this article depend heavily on volunteers, there are very few career fire- fighters. In areas such as Glen Haven, a non-incorporated community in Larimer County, “every pair of hands and feet were working to fight the fire,” Zagorda said. Both of these fires ended up burning approximately 400,000 acres in northern Colorado; the East Troublesome came in just behind the Cameron Peak fire to be the second largest fire in Colorado's history. Within Rocky's boundaries, 30,000 acres were burned – more than in any other in its 106-year history. Both of these fires, along with most of Colorado's wildfires in 2020, were human caused; the exact causes are under investigation. Since wildfire isn't going away, it's clear the biggest lessons learned from these fires is that the general public needs to become more educated on their responsibilities while recreating in the wilderness Each of these agencies provide community resources on their websites. Visit the Glen Haven Area Volunteer Fire Department at www.ghavfd.org Schelly Olson has created a nonprofit organization called the Grand County Wildfire Council: bewildfireready.org/ Grand Fire Protection District 1 can be found at grandfire.org/ The Estes Valley FPD's website is: www.estesvalleyfire.org/ Rocky Mountain National Park's fire management office can be found here: www.nps.gov/romo/learn/management/firemanagement.html Cover Story for the October 2021 edition of HIKE ROCKY magazine “I cannot endure to waste anything so precious as autumnal sunshine by staying in the house. There is no season when such pleasant and sunny spots may be lighted on, and produce so pleasant an effect on the feelings, as now, in October.” - Nathaniel Hawthorne, from The American Notebooks story and photos by Marlene Borneman Just as wildflowers blooming in summer bring us joy, autumn brings fresh pleasures. The most recognized natural fall spectacle in Colorado is the changing colors of aspen leaves. Quaking aspen, Populus tremuloides, is a hardy deciduous tree native to North America. The leaves are small heart-shaped with fine serrated teeth on the edges. The white bark is smooth which becomes rutted and uneven with age. Deciduous trees lose their leaves each winter. But it all begins in summer when there is an abundance of sunlight which aspens use along with water and carbon dioxide to produce oxygen and energy in the form of sugar. This process is known as photosynthesis. The green pigment chlorophyll is responsible for the absorption of light to help produce the energy (sugar) and hides the yellow, oranges, reds, that are true colors of the leaves. Many internal chemical changes occur in aspens during the fall. At the autumnal equinox and during the days following, there is less sunlight which results in leaves making less sugars, thus less chlorophyll is needed. The trees stop storing sugars and go into a dormant state for the winter months. When this process starts to happen, the pigments carotenoids and xanthophylls become visible bringing out yellow and orange colors.  Detail of an aspen leaf in transition Detail of an aspen leaf in transition So, what about aspens that turn a brilliant red? Less sunlight also signals the aspen trees to form a blockage layer (called the abscission), preventing any sugars from passing between the leaf and the rest of the tree. During this process sugars may get trapped inside the leaf when the abscission layer is being formed producing the pigment anthocyanins. The higher the concentrations of anthocyanins, the deeper the crimson red hues. Each year aspen trees can produce a different set of colors depending on conditions in the environment during the formation of the abscission layer. Elevation, temperature, and moisture are variables that influence the timing of leaf change and intensity of color. The ideal circumstances for a brilliant display are sunny days and cool nights.  Snow plow operations in late September on Trail Ridge Road Snow plow operations in late September on Trail Ridge Road A great way to drench yourself in autumn gold is with a backpack trip to the west side of Rocky. My husband, Walt, and I planned a trip to Lake Verna the day before the autumnal equinox in hopes of catching some colors. The day before our trip, a fast-moving storm system deposited snow, closing Trail Ridge Road for a few hours. We checked the status of the road the morning of our drive to find it had re-opened. Rocky Mountain National Park is full of surprises so take seriously the posted signs that read “Be prepared for rapidly changing weather.” The road up high was snow covered and icy with seventeen degrees at the Alpine Visitor Center! After passing a snowplow, I thought to myself no winter boots, no gaiters, and no micro-spikes. And maybe, no backpack trip. Dropping down into the Kawuneeche Valley, we found a pleasant surprise: only a scattering of snow on the mountains and a balmy forty-eight degrees in Grand Lake.  The author at Lone Pine Lake The author at Lone Pine Lake  Adams Falls Adams Falls The trail to Lake Verna begins at East Inlet trailhead. The first hint of the stunning scenery on the East Inlet is Adams Falls, only 0.3 mile from the trailhead. From here, the trail rises moderately following the creek until reaching switchbacks. Then the trail becomes steeper as it leaves the creek. The East Inlet trail is a good example of trail crews' hard work with many rock steps, fine bridges and retaining walls for hiker's comfort, safety, and prevention of erosion. Soon we are immersed in deep golds, bright oranges, and reds of aspens. By the time we reach Lone Pine Lake it is a warm, sunny autumn day! At about 10,600 feet we see snow lingering in the trees with heartleaf arnicas still in bloom. Another surprise. Lake Verna is the largest along a chain of five lakes in the East Inlet drainage. The old-timers in Grand Lake used to call these the String Lakes; Lone Pine Lake, Lake Verna, Spirit Lake, Fourth Lake and Fifth Lake. There are eight backcountry camp sites along the East Inlet Trail. In past years we have snagged Lake Verna site but this time we are at Solitaire, 6.2 miles from the trailhead. After setting up camp we head for an evening tour of picturesque Lake Verna. Legend has it Lake Verna was named for the sweetheart of a member of the U.S. Geological Survey. The identity of the survey, surveyor and the sweetheart is unknown which makes for good storytelling around camp. The landscape seems so still and quiet as it slowly transitions from season to season.

All along this drainage many stately towers and pinnacles rise above the lakes making a dramatic scene. At 10,300 feet Spirit Lake glistens under the rock tower known as Aigiulle de Fleur which can render one speechless with its hefty but graceful presence. Fourth Lake is next on an unimproved trail with many huge down trees to negotiate over and under. Some of the down trees are the results of a derecho last September before the Troublesome fire raged through the park. Derecho is a type of windstorm with straight- line wind damage in a swath over a large area. The unimproved trail gets very faint after Fourth lake and almost non-existent to Fifth. Remote and striking Fifth Lake sits under the stately towers of Isolation Peak and along the ridge of The Cleaver. Marlene has been photographing Colorado's wildflowers while on her hiking and climbing adventures since 1979. Marlene has climbed Colorado's 54 14ers and the 126 USGS named peaks in Rocky. She is the author of Rocky Mountain Wildflowers 2Ed, The Best Front Range Wildflower Hikes, and Rocky Mountain Alpine Flowers. Snowy Peaks Winery in Estes Park is a supporter of HIKE ROCKY magazine and sponsors the publication of this story.

from the October 2021 edition of HIKE ROCKY magazine story and photos by Rebecca Detterline The snow at Thunder Lake was definitely deeper than anticipated on a recent attempt at a few remote peaks in Wild Basin. It quickly became obvious that our original plan would be thwarted by the slick conditions resulting from the first snowfall of the season. Knowing that our hike would be considerably shorter than we had prepared for, my two girlfriends and I hopped from rock to rock, following the steep trail that leads hikers from Thunder Lake to Lake of Many Winds, occasionally post-holing into calf-deep snow. Our feet were already cold and wet, and each step into the fresh snow packed a bit more snow into our sneakers. Visibility was poor and it would have been unwise for us to travel to the high and exposed peaks of Wild Basin with no traction or mountaineering equipment. However, moments of sunshine and breaks in the clouds revealing views of Longs Peak and Mount Meeker made our chilly feet nothing more than a small annoyance. Winds were relatively low and we knew we were only a mile and a half or so from the dry Thunder Lake Trail. ‘Have you ever been up Mount Alice?’ I asked my friend Kirby. She hadn’t. ‘How about Boulder-Grand Pass?’ Negative on that one as well. Unbeknownst to me, the trail that we were hiking on was completely new to her! She had never traveled past Thunder Lake toward Lake of Many Winds. While I love to stand on a summit or dip my toes in an alpine lake, I am definitely a hiker who enjoys the journey as much as the destination. I will not hesitate to hit the trail in the drizzling rain or on a day with a 90% chance of precipitation knowing that my original objective is likely unattainable on that particular occasion. There are so many worthy destinations at and below treeline in RMNP and I am always happy to don a rain jacket and gloves and revisit Ouzel Falls or Lake Helene or any other number of places I have seen about a million times. That being said, Kirby’s revelation that she had never been to Lake of Many Winds absolutely made my day! ‘You only get to see a place for the first time once!’ I beamed and we plodded up the last half mile of trail to the aptly-named lake, taking in the views of the high peaks surrounding us while Thunder Lake glistened below. This snowy hike in glorious Wild Basin was one of many opportunities this summer to share my favorite places with people who had never seen them before. I am not quite Jim Detterline-level when it comes to revisiting a place over and over. However, I am pretty sure that I hold the world record for most ascents of Eagles Beak. I have no idea how many photos exist of me in front of Ouzel Falls, but it has gotten to the point where I politely decline friendly bystanders’ offers to take my photo there. I think I have every season, every type of weather and every time of day covered. As much as I love visiting these places that have become like old friends and constants in times of uncertainly, the real joy comes from sharing these gems with others. One summer I stood on top of Longs Peak seven times, each time with folks who had never been there. I don’t anticipate another season like that, but I am always up for sharing my favorite lakes or remote summits with friends who are excited to see them. There are plenty of destinations in RMNP that I have not visited. I am not the type of person who needs to stand on top of every scree-laden summit in the Never Summer Range. I don’t have a checklist of destinations that I am hell-bent on reaching. I don’t know how many times I’ve scrambled up Pilot Mountain or The Cleaver. I do know my favorite destinations so far, though, and I tend to return to them year after year. While I enjoy revisiting these places with my regular hiking partners, the greatest joy always comes from showing someone a place for the first time. Being able to take my friends to places they have never seen is an honor and a blessing. Traveling safely through RMNP is a learned skill and I have certainly been on the receiving end of guidance from those more accomplished than myself. This summer I was blessed to traverse Blitzen Ridge to the summit of Mount Ypsilon. Thanks to an experienced partner, I didn’t have to worry about route finding and I was able to relax and enjoy the views of Spectacle and Fay Lakes from the Four Aces. I’ll never forget the first time I walked across Broadway Ledge on Longs Peak, tied into a rope and plucking out protection as I meandered toward Upper Kieners. I never could have guessed that parry primrose grew on that grassy ledge that appears so cold and rocky from afar. Any day spent in the mountains of RMNP is a gift, but the best views I have found are the ones standing alongside a friend who is seeing a place for the very first time.  Rebecca Detterline is a lover all things RMNP. She is a wildflower aficionado whose favorite hiking destinations are alpine lakes and waterfalls. Her name can be found in remote summit registers in Wild Basin and beyond. Originally from Minnesota, she has lived in Allenspark since 2011. |

Categories

All

|

© Copyright 2025 Barefoot Publications, All Rights Reserved