|

by Rebecca Detterline In the winter of 2017, while making plans for a hike to Blue Lake, a friend asked if I owned ice skates. Growing up in Minnesota I think every kid had ice skates, but somehow mine never made the journey to Colorado. Almost everyone in Minnesota knew how to ice skate. Whether they just strapped on a pair of rentals for the annual elementary school field trip, played hockey at the outdoor rink found in every single small town, or, like me, walked down to the nearest lake dotted with fish houses and skated clear across to the other side, it was pretty rare to make it through one's formative years without at least giving ice skating a try. Back to Blue Lake. Since I didn't have skates, my dear friend had secured a pair from someone with feet probably two inches longer than mine, so I laced them up as tight as I could and headed out onto the lake. I consider myself to be relatively athletic, but with the skates that were a couple sizes too big and Blue Lake being covered in miniature ice moguls, I looked like Bambi attempting to learn to walk on a frozen pond! How could I have unlearned such a simple skill in twenty short years? Luckily, I made it off Blue Lake unscathed and and headed down to Black Lake, which was in incredible shape for ice skating, where we skated for another hour and I felt that I was able to redeem myself as a Minnesota girl. Compared to other winter activities in the Park, ice skating the price of equipment is relatively low. Ice climbing, mountaineering and backcountry skiing require loads of specialized gear, not to mention an experienced partner, mentor or guide. I've also noticed that the dollar-to-fun ratio seems a bit questionable when it comes to snowshoes. Ice skates, on the other hand, are available at any number of sports equipment consignment shops along the front range for $50 or less. In order for conditions on the alpine lakes to be suitable for enjoyable ice skating, it seems like conditions for all other winter activities have to be terrible. Lack of snow and high winds are the recipe for clear ice up high. Ice skating is a blast, but fires are terrifying, so I will take the snow every single time, even if it means I have to attempt to clear off a 10x10 foot area with an avalanche shovel. With the exception of Lake Haiyaha, which seems to miraculously repel snow during the winter months, hiking to an alpine lake with grandiose plans to skate on smooth, clear, snow- free ice can lead to disappointment. Luckily, my friends are running around RMNP all winter, sharing photos on social media, so that I know in advance whether my lake of choice will be a glassy, ice skater's paradise or a field of dense impenetrable snow. Without an updated conditions report, it's probably best to not to make ice skating one's primary mission. Rather, plan an enjoyable winter hike, pack the skates, and treat ice skating as a bonus activity. Skate guards are essential to avoid damage to one's backpack, favorite puffy jacket, or—heaven forbid—water bladder. This risk, coupled with the bulkiness of ice skates and my affinity for a small backpack have had me seriously considering trying out the antique strap-on skates that sit atop my mantle as decoration. Although I've historically been able to find a relatively smooth spot on most alpine lakes, learning to ice skate on them is not ideal. I vividly remember a day on Sprague Lake last winter when it seemed like someone must have snuck a Zamboni unto the ice; it was that smooth! I wonder if I will ever experience conditions like that again. I'm definitely not holding my breath. For children and beginners, YMCA of the Rockies and Trout Haven offer ice skate rentals and onsite skating rinks. For those looking to givethe alpine lakes a whirl, the Mountain Shop offers daily rentals that can be taken into the Park. Although the wind is usually blowing and my ice skates are freezing cold when I pull them out of my backpack, once I start skating, I never want to stop! Ice skating in Rocky Mountain is a truly magical experience. I have been lucky enough to ice skate on Chasm Lake on a sunny day with Longs Peak looming above, so I guess that I have been lucky enough.  Adeline Williams and Rebecca Detterline skating at the YMCA of the Rocky's Dorsey Pond. Adeline Williams and Rebecca Detterline skating at the YMCA of the Rocky's Dorsey Pond. Rebecca Detterline is a lover all things RMNP. She is a wildflower aficionado whose favorite hiking destinations are alpine lakes and waterfalls. Her name can be found in remote summit registers in Wild Basin and beyond. Originally from Minnesota, she has lived in Allenspark since 2011.

2 Comments

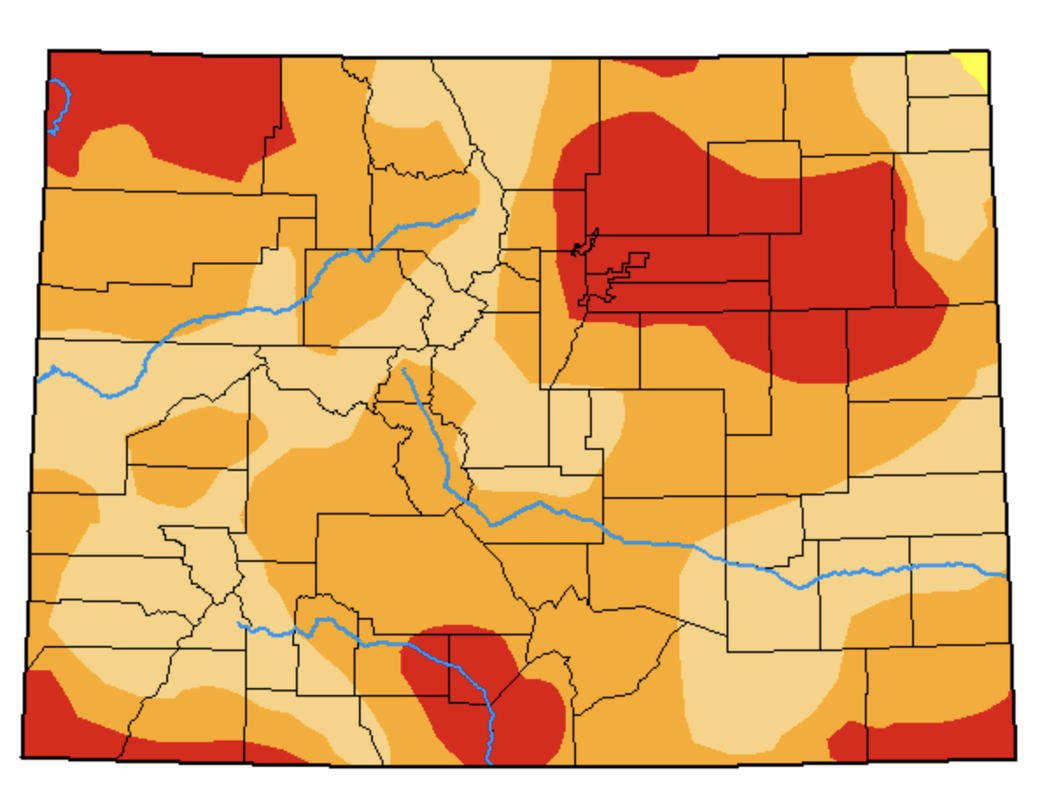

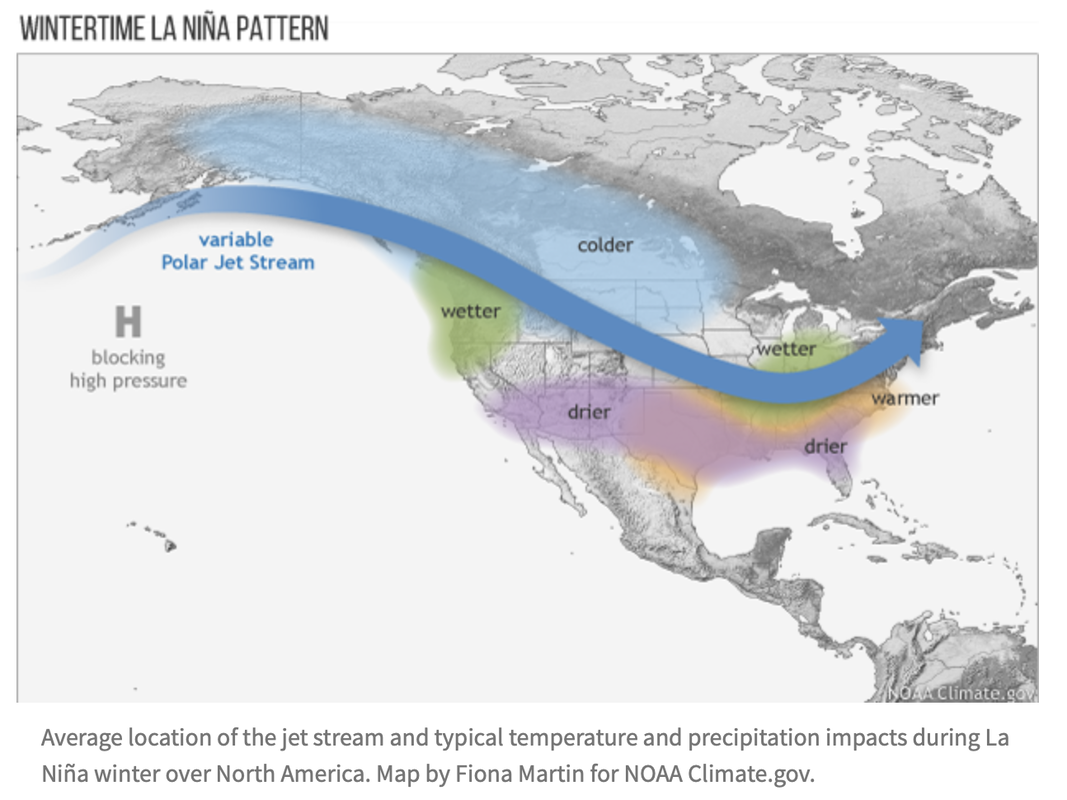

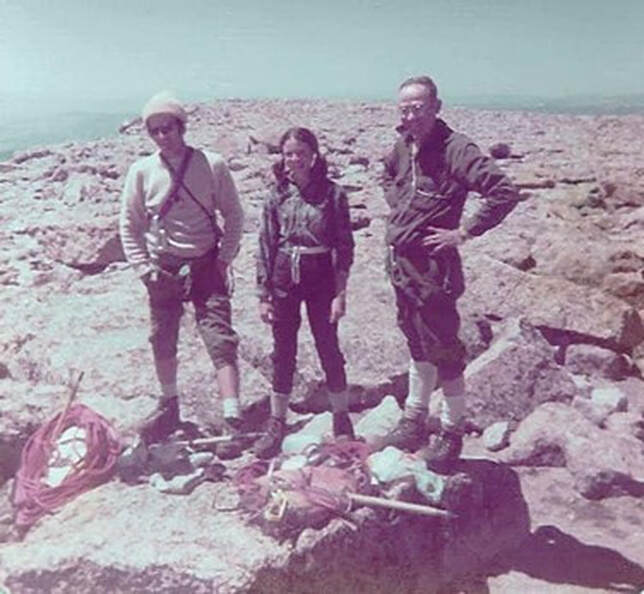

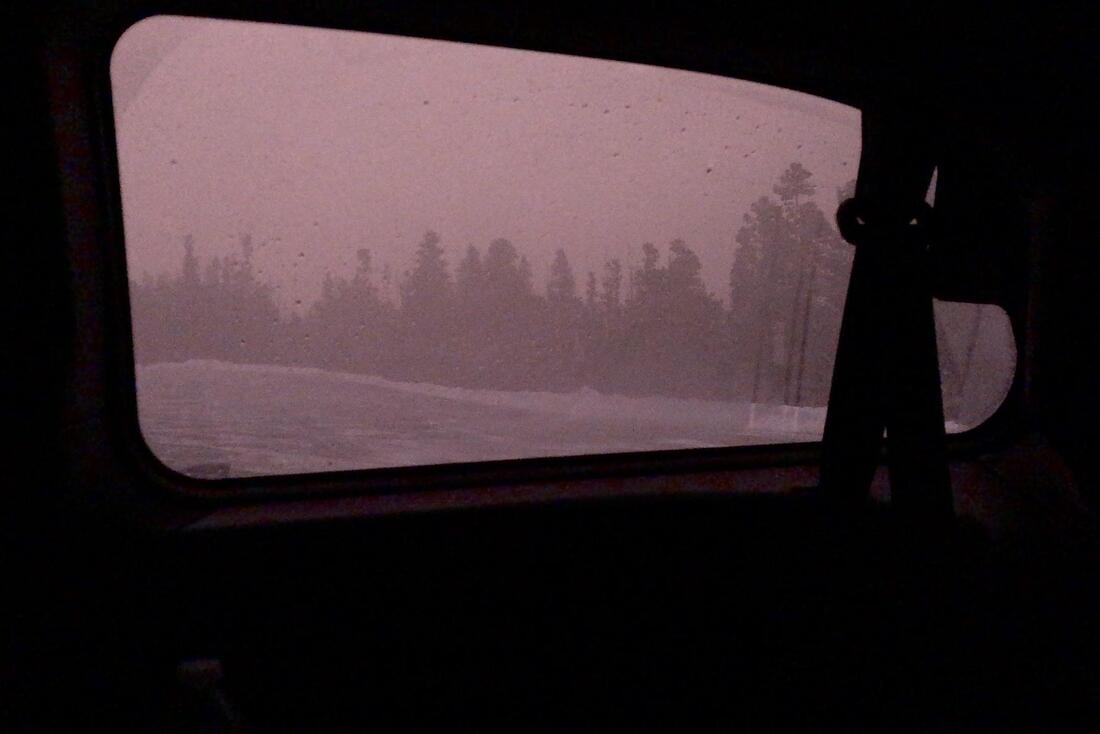

story and photos by Marlene Borneman editor's note: this story is pulled out in its entirety from the February/March edition of HIKE ROCKY digital magazine. For more information about the magazine visit this page Finch Lake: 10 miles round trip Elevation: 9,912 feet Elevation gain: 1,432 feet Finch and Fern Lakes are destinations I have been to many times in every season. People often ask me if I get tired visiting the same places over and over. The answer is always “no.” For me each outing in Rocky is different. Sometimes I go solo or with a variety friends, different wildlife sightings, weather, terrain, and seasons. The surroundings and circumstances change, making each excursion a unique experience. I've been surprised by fresh avalanche disturbances, high water, bridges out, snowdrifts, downed trees, a new wildflower, and fresh conversations. On January 9th I started with friends to snowshoe to Finch Lake from the Wild Basin trailhead located in the southeast corner of RMNP. Wild Basin is a place very dear to my heart. This section of the park is “wild” and packed with alpine lakes, deep flowing rivers, waterfalls, high majestic mountains, and imposing passes. Strapping on snowshoes, we started out on a snow- packed trail. Soon, we headed east, contouring the north side of a long moraine. This part of the trail is frequently icy, but that day we found deep fresh snow. As we gained the ridge and then over, we dropped down to a pretty meadow with aspen groves. In summer months, this meadow would be filled with a variety of wildflowers, but that day it was a blanket of snow. Not only did we find substantial snow but what seemed like hundreds of slash piles randomly stacked throughout the meadow. The scene evidenced the hard work of fire management staff in a fuel reduction project. We circled the maze of slash piles with no trace of the trail. It was very disorienting to be among these scattered slash piles. There were snowshoe tracks going in every direction, possibly the fire management crew or perhaps some other disoriented hiker. We were certainly not lost. We knew about where we were on the map but didn't know exactly where the trail was located. It was then I realized how much trees give definition to trails, especially in winter.  Looking west I kept heading across the meadow and then into heavy forest and whoa - I see the first trail junction signage for the Allenspark area. I knew the trail from here goes steeply up with several switchbacks to the next trail junction. It helped that the slash piles stopped at this first junction so that trail became more distinct through the stands of lodgepole pines. After a steep climb through deep snow, we came to the Allenspark Trail/ Finch Lake Trail/Calypso Cascades junction. By now it was noon and time for lunch. We all took pleasure in the stunning view of the south side of Longs Peak, Mount Meeker, Pagoda Mountain, Mount Alice, and Chief's Head. The Finch Lake trail was not broken from this point and we wisely decided to head back retracing our steps. We did not reach Finch Lake, nevertheless a worthwhile day exploring. Fern Lake: 7.6 miles round trip Elevation: 9,540 feet Elevation gain: 1,390 feet On a chilly January 21st morning my husband and I started out for a snowshoe trip to Fern Lake. The trailhead is tucked in the northwest corner of Moraine Park. In winter, this hike requires an extra .7 mile of hiking on a road to the trailhead. In the 1900s, the Fern Lake Trail Trail was used by lodge owners, hikers, horseback riders, snowshoers, and skiers. Fern Lake Lodge was comprised of a central lodge and several cabins. Weary visitors could buy refreshments and/or spend the night in the comforts of the lodge enjoying stories told by the owners. It was a popular winter destination. However, in the forties and fifties it was open only in the summer months. The lodge experienced several owners and unfortunately many pilfers and vandalism. The lodge was closed by the Park Service in 1952 and then the remaining structure was burned by the Park Service in 1976. The Old Forest Inn was another well-visited lodge located three and half miles from the trailhead above The Pool. This was a smaller lodge with several platform tents scattered to serve visitors. The Old Forest Inn was closed in 1952 and then dismantled in 1959. Now an established campsite on the site bears the name Old Forest Inn. Fern Lake Trail was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2005 to commemorate the role it played in the Park's tourism industry. 2012 brought a fire to this trail caused by an illegal campfire. The rements are still evident today. In 2013 a major flood along the Front Range also impacted the Fern Lake Trail washing out a section. Then in October 2020 the East Troublesome Fire brought more devastation to the area. The trail was closed for some time as burned down trees covered the trail, unstable standing trees, burned bridges and hot spots remained for a long period. If the Fern Lake Trail could speak, what would it say having witnessed so many early visitors in every season and surviving destruction of fires and floods? We have hiked this trail in summer and winter since the East Troublesome fire finding it very altered and very resilient. What stands out for me, besides the burned forest, is that the Big Thompson river is now very visible from the trail whereas before thick foliage hid the view. We found the trail to be easily negotiated with just micro-spikes up to The Pool.  We carried our snowshoes, so we were prepared when we reached deep snow ahead. I had forgotten how stunning the scenery is along the Big Thompson River especially in winter with icy formations in the snow-covered river with fast moving water peeking through. We first come to Arch Rocks so named for the huge granite boulders sitting upright at angles. As we walked through Arch Rocks we found several piles of elongated rounded ends “milk-dud” shaped scat and a few moose tracks in the icy trail, but no actual moose. We worked our way along the river as the trail became steeper. In 1.75 miles we reach a place simply called The Pool. Named for the deep granite bowls holding churning waters at the confluence of Spruce and Fern Creeks with the Big Thompson River. On that day The Pool was stilled by ice and snow. After crossing a sturdy bridge over the Big Thompson River the trail goes up to the right with a sharp switchback. We found the snow had drifted over the trail resulting in a steep slope. We saw others had avoided this crossing and gone straight up to contour over a small rise and back down to the trail. We did the same avoiding the steep snowbank. We quickly traded our micro-spikes for snowshoes. Little did we know what waited for us further up the trail. We crossed a large new bridge spanning Fern Creek. The bridge was recently replaced due to the East Troublesome Fire. We again found ourselves in a midst of charred trees gaining altitude at a steady rate along several switchbacks. Despite the fire scars this area still shows off a true winter wonderland with views up Spruce Creek. The higher we climbed, we encountered more huge snowdrifts across the trail. These snowdrifts made it difficult to stay on the trail. We wandered up and down and around these huge snowdrifts and finally got to a spot we thought was the long switchback to Fern Falls. We snowshoed towards the sound of fast- moving water and then looked down at the river below but no falls. We backed tracked a bit and then climbed back up to what we were sure was the switchback above the falls. The terrain became one large steep snowdrift! In each direction no standing trees just open burned forest. Again, a very disorienting situation. We crisscrossed several times to the area around Fern Falls, but no falls. We had not seen anyone all day and then suddenly two men appeared coming toward us. After a greeting they explained they did not find Fern Falls either but had arrived at Fern Lake via GPS. We all commiserated how different the landscape appeared with the huge snowdrifts and burned forest. As the two men headed down, we found a perfect overlook for a well-deserved lunch. It was a humbling spot overlooking Forest Canyon and Tombstone Ridge. We are kind of feeling discouraged by not reaching Fern Lake or even Fern Falls! Suddenly, it begun to snow heavily. Laughing out loud feeling a bit silly, yet acutely aware of our charmed day we took our time eating lunch appreciating the location (wherever that was?). “It's not about the destination, it's about the journey.” This familiar quote came to mind after these two recent snowshoe trips. I thought “It's ok not to reach the day's goal.” There is no measurement for experiences, friendships, and good old-fashioned exercise in the great outdoors.  Marlene has been photographing Colorado's wildflowers while on her hiking and climbing adventures since 1979. Marlene has climbed Colorado's 54 14ers and the 126 USGS named peaks in Rocky. She is the author of Rocky Mountain Wildflowers 2nd Ed, The Best Front Range Wildflower Hikes, and Rocky Mountain Alpine Flowers. Story, photos & video by Dave Rusk The Bear Lake trailhead is, without a doubt, the most popular trailhead in Rocky Mountain National Park. I think it's fantastic that there's a mountain lake so accessible to a great many people who otherwise might never get to see such majestic beauty. For many others, going a farther 1.1 miles to Dream Lake is challenge enough but with an unmatched mountain experience. It's always astonishing to me that this trail isn't more beat up and worn out given the thousands of hikers that trek to see the Dream each year. Tucked off from this well-visited trail is the Lake Haiyaha trail. Even though it's only 2.2 miles from the Bear Lake parking lot, the lake is often overlooked by the many Dream Lake trekkers. In fact, because the Bear Lake parking lot is so full of Bear Lake and Dream Lake hikers, this lake is often less visited than it might be. It is a lake with a pronunciation that even laughs at itself (just remember when trying to spell it, the “a” goes before the “i"). They say the name means “rock” and indeed there are boulders strewn about everywhere in Chaos Canyon that stretches above the lake. In early November, I hiked to up to Lake Haiyaha to see how the snow conditions were faring (see the video). Starting the hike at 9,475 ft., the trail rises up 745 ft. to an elevation of about 10,220 ft. While Rocky had experienced some October snow storms, most of the trail conditions at that time were icy with very little snow coverage, until I got above 10,000 ft. When I was there, the lake was mostly frozen over, but not solid enough for ice skating just yet. When I reached the lake, the wind was blowing hard down Chaos Canyon.  I returned to the lake again in mid-December and found the conditions had become much more winter-like with more snow and cooler temperatures. Some early December snows brought increased snow coverage down to below 9,000 ft. covering over any icy spots on the trails. While snow travel even at 10,000 ft. did not yet necessitate snowshoes, a decent snowpack was beginning to set up. The wintery conditions I found in mid-December had not been aided by our November weather pattern. In fact, according to the November Climate Summary Report from the Colorado Climate Center, this year's November was the third warmest for the state and ranked as the 11th driest on record. In short, our November was warm and dry, increasing drought conditions in our region to moderate and running the snowpack for the early season to below average. Colorado state climatologist Russ Schumacher is blaming a La Niňa ocean pattern in the Pacific that typically shifts moisture farther north. Whether any of that moisture will drop down in latitude on our mountains will largely depend on where the Jet Stream sets up. NOAA forecasters are “confident” that the La Ni~na pattern will persist through the winter. However, Schumacher did add, “It's still very early and a lot can change between now and the spring,” hedging his bets, like any good weather forecaster would. I hope change comes. But winter had set in up high and the six or so inches of snow on the Lake Haiyaha trail was getting packed in. In the summer, this trail is a pretty nice moderate hike with good views of Longs Peak and the Glacier Gorge region along the way. But in the winter, it can be a different game. While the winter trail to Dream Lake sees lots of travel and is usually well established, the number of snow travelers drops off considerably for the Lake Haiyaha trail cutoff. A good snow storm can quickly cover over the existing snow-packed trail and it could be easy for whoever is breaking the new trail at the time to get off course, leading followers astray. What seems like a relatively nice winter venture could get tricky real quickly if someone not familiar with the surrounding terrain were to accidentally drop down into the Chaos Canyon area under less than favorable weather conditions. On the day I went, the fresh snow was good and there was a decent path that stuck to the trail. Though the temperature was cool, I had to continually pull my cap off to keep my head from over heating and getting too sweaty. It can be easy to overheat when hiking in winter conditions and then become quickly chilled in the wind when stopping for a rest. There were several small groups that were making their way to the lake while I was out. One gentleman had even brought ice skates! Once I got to the lake, I found the wind was still blowing hard down canyon.  Dave Rusk has been sauntering and taking photographs through Rocky Mountain National Park for decades. He is the author publisher of Rocky Mountain Day Hikes, a book of 24 hikes in Rocky, and the website of the same name. He is the publisher of HIKE ROCKY Magazine and an important content contributor to all of these endeavors. Story and photos by Marlene Borneman It began innocently enough, in 1974. l came to Colorado for a summer job at the YMCA of the Rockies in Estes Park. I arrived from New Orleans (yes, below sea level) in mid-May of that year and, being a proper young lady from the South, l wanted to make a good impression on my new employer. l wore a sleeveless silk dress (rather short as I recall), stockings, and the cutest little heeled sandals you ever laid eyes on. It was somewhere around 30 degrees and spitting snow. It turned out to be one of the scariest days of my young life. All l could think was, "l have made a terrible mistake!” Fortunately, those feelings didn't last all too long. Once over the cultural shock of my summer home, I seeded into the rhythm of working and learning about a phenomenon called "hiking." I was fortunate to meet Dick Chuttke. He was a retired gentleman, a YMCA member, and a Colorado Mountain Club member who enjoyed hiking with the YMCA groups. Ironically, he suffered from acrophobia, an irrational fear of heights. He became my climbing mentor for the next 20 years; he taught me how to be fast and careful at the same time and instilled in me the ethics of Leave No Trace before it was popular or common. From short silk dress to summits, my progression came fast. By the end of that summer, I had climbed most of the major peaks in Rocky Mountain National Park. Having graduated from college, l decided to stay in Colorado. You might say the rest is history, but it was not that simple. I lived in Estes Park for 12 years and climbed in the park year-round. I found myself focused on the major peaks, and their different routes, with a few new peaks thrown in now and again. Then came a career move away from Colorado; to say I began grieving would be an understatement. But, by 2001, I had returned to live full time in Estes Park. After completing 54 fourteeners in 2005, I was hit with the pain of guilt. I imagine you all know what it's like to ignore a friendship. This was worse: it was like neglecting your own husband. After all, Rocky Mountain National Park was now in my backyard. I began to rekindle my relationship with Rocky, and started studying the map with new interest and curiosity. When you get down to it, though 35 years had passed Dick's spirit motivated me to complete the 126 named summits in Colorado's crown jewel. This was the project I needed to turn neglect into passion. First, I carefully laid out the list. There were 35 peaks in Rocky I hadn't yet climbed. By the summer of 2009, I had only three to go. Then reality struck me hard. The final three were The Sharkstooth, Hayden Spire (both Class 5, technical climbs requiring ropes and equipment) and Pilot Mountain (a difficult, though less technical, Class 4 climb). Had I set myself up for this? Shouldn't the last peaks be easy, like Estes Cone or Twin Sisters? I hadn't climbed anything beyond Class 4 in years. I lost some sleep, talked incessantly to my husband, and consulted every book and person whom I thought could set my mind at ease. Then I came to the realization that the final three were meant to be my grand finale. I needed a challenge; I wanted a challenge. I needed to gain my confidence back on the rope; I needed a plan. It felt like I needed a lot. The Sharkstooth was the first of my final three and, as it turned out, my most challenging climb in Rocky. My climbing partner and I left the parking lot at 3:45 a.m. I once read that eighty percent of success is just showing up. I liked my chances. The sky turned cloudless: a deep blue, Colorado morning without a breath of wind. We would be climbing the East Gulley Route (5.4). The first pitch was going easy enough on ledges, until we came to a short, but very exposed traverse. I watched my partner go across with ease up to a small crack, out onto a smooth rock face, then scramble up another crack. Traversing the ledge looked feasible but when I came to the first crack, I just couldn't visualize the move. I stared at it for what seemed like an eternity. Here I was, committed to this menacing climb, and the first move was proving to be baffling. The staring must have helped. Finally, it all came together and it was over, behind me. I was sweating like a pig. Good thing I had given up that silk dress. Things were going smooth until the crux: a wall of 60 feet, extremely exposed. Once again, I was paralyzed. I found myself looking at this wall, caught in my own world for endless amounts of time. I had watched my partner climb straight up with ease. Finally, I took a deep breath and let it out slowly. I knew I needed to move quickly; no hesitating, just go. I stepped out onto the wall and got my fingers into the crack, trusting my climbing shoes to hold onto what seemed to be nothing and scampered up. Though my stares felt eternal, my moves seemed mere flashes; I was on top of the cliff. As I climbed toward the summit, tears were in my eyes. This was what it was about: I hadn't gotten here because of a list, but because I had taken a risk. Ultimately, I reached the summits of the final three with a smile from ear-to-ear. I found myself enjoying these peaks more than I imagined. I will forever remember the air beneath my feet, the sudden flight and song of finches above my head, the simultaneous sense of inner relaxation and burst of excitement, and the incredible sound of the silence around me.  Rappelling down Hayden Spire in 2009. Rappelling down Hayden Spire in 2009. You may ask, is there anything left of that southern girl from 1974? My father was a riverboat captain, checking catfish lines across the river while trolling for shrimp in Lake Pontchartrain at 5 a.m.; he lived with patience, endurance and perseverance. I gained these traits from him. Maybe this is why I adapted so well to the mountains and persevered to the top of 126 of Rocky's best.  Marlene has been photographing Colorado's wildflowers while on her hiking and climbing adventures since 1979. Marlene has climbed Colorado's 54 14ers and the 126 USGS named peaks in Rocky. She is the author of Rocky Mountain Wildflowers 2nd Ed, The Best Front Range Wildflower Hikes, and Rocky Mountain Alpine Flowers. Story, photos, and video by Murray Selleck, HIKE ROCKY Equipment Specialist. Please note: these reviews are not solicited, and we received no financial compensation for these reviews. Snowshoeing is a wonderful winter extension of your love for hiking in the summer. All your favorite summer trails in Rocky Mountain National Park become easily accessible winter trails with a pair of snowshoes. Snowshoeing offers a completely different yet intimate wintery mountain experience. The soothing yet smothering quiet of a snow-filled forest when you compare it to the noise of our frenzy paced towns and cities is comforting. Watch out when the wind releases snow-loaded pine branches of their wintery burden. Count yourself lucky if one of these big clumps of snow doesn't target you from above. The resulting whomp whomp whomp of these big clumps of snow hitting the snowpack will have you hunching up your shoulders just in case! The sound of your snowshoes compressing soft powdery snow underfoot along with the cheering chirps of mountain chickadees will only make you want to snowshoe farther and deeper into the forest. Yes, snowshoeing really is quiet, wonderful, and peaceful. A challenge all snowshoers face isn't the activity of snowshoeing itself. Everyone can enjoy snowshoeing, from youngsters to oldsters alike. No, the challenge is deciding which pair of snowshoes is right for you. A quick count of companies producing snowshoes these days is up around 24. Back in the mid 80's when snowshoeing saw a huge resurgence, Redfeather Snowshoes was practically the one and only choice. Snowshoe deck sizes, snowshoe talons, crampons and cleats for traction, frame designs, bindings. All these features will come into play while you’re making your decision. Here are some initial tips for you to consider when making your purchase. Pretty much all snowshoe manufacturers publish a weight range for each size snowshoe they make. This is helpful but typically the weight range is so broad it includes all of us anyway. When I help folks choose a snowshoe I ask them to consider where they are likely to snowshoe most often. Will you be snowshoeing on a packed trail or do you like to explore, go your own way, and break a fresh trail in deep snow most often? Will the terrain you like to snowshoe on be more golf-course like or mountainous with lots of climbing and descending? The answers to these questions will help determine snowshoe deck size and how aggressive the traction crampons or talons underneath the deck should be. For packed trails and tamer terrain, you can choose a smaller frame for an easy lightweight and more maneuverable snowshoe. For more adventurous terrain and breaking trail in deeper snow you'll benefit from a larger snowshoe for more floatation with more aggressive traction talons underneath. A retractable climbing bar is a great performance benefit. And what if you think you will be snowshoeing a bit in each situation? The middle ground is a good compromise as long as you're aware of the pros and cons of your choice. On packed trails a larger snowshoe can feel a little clunky. A smaller snowshoe in deep snow will make breaking trail tougher (but not impossible). Both will work in either snow condition but it is the awareness of how your snowshoe will perform in each condition that allows you to make those compromises. Women's specific snowshoes typically have all the same features of a guy's snowshoe but the frame is narrower. A narrow snowshoe helps women stride more naturally avoiding the infamous “clam diggers” walk as if walking through tidal mud flats. I like to snowshoe with poles. Even on mild terrain a pair of poles lets my arms and hands, shoulders and torso become involved in the activity. Poles help you climb more efficiently and they provide additional stability on steep descents. Of course, budget will determine your comfort level with a snowshoe purchase. And as usual, you get what you pay for applies to snowshoes, too. The more dollars you are able to put towards your snowshoe purchase you will be rewarded with long term durability and no- fuss binding reliability. The last tip is to try the snowshoe binding in the store. Bring the boots you are likely to wear while snowshoeing so you can try them on. Go ahead and strap on the binding to determine ease of use and retention. There really is no good reason to have to readjust your bindings while snowshoeing. The only time you should adjust the binding is putting them on or taking them off, not while you're on the trail. Here are three snowshoe manufacturers that I really like and have had good experiences with. TSL Snowshoes TSL is a French company and their snowshoes are manufactured in France. If anyone has really made some nice snowshoe design strides over the last few years it is TSL. Their Symbioz models feature HyperFlex. The snowshoe has a wonderful round flex pattern that allows you to walk and hike with a very natural heel-to-toe stride. You feel this feature especially on packed trails and descents. The bindings have some great adjustment features. The length and width of the binding can be adjusted for boot size. The most unique aspect of the length adjustment is the climbing bar is always in the perfect position under your heel. The retention strap that comes forward over your ankle adjusts easily with a ratchet and is easy to reach. Some traditional heel straps can be low to reach and awkward to adjust. TSL does not make men's or women's specific models. They do make 3 different sizes in each model. Small, medium, and large sizes cover your snowpack and trail considerations. Their hourglass frame shape makes for an comfortable stride (along with HyperFlex). Do yourself a favor and check out all the TSL snowshoe models. Atlas Snowshoes Atlas has a complete line of snowshoes from models that are appropriate for a snow covered golf course to snowshoes that are ideal for very adventurous terrain. One terrific snowshoe model that's right in the middle of their line is the Montane. The Montane comes in men's and women's models and sizes. Women's snowshoes are narrower than a men's snowshoe. The narrow design allows women to achieve a more natural stride. One of the best features with Atlas is their spring loaded or SLS binding. Spring loaded allows the tail of the snowshoe to lift off the snowpack as you step forward, reducing tail drag. It also helps the tip of the snowshoe to lift up and over the snow as you step forward breaking trail. The Montane has an easy one-pull-loop to close and a one-pull-loop to open to open the binding with a more traditional heel strap. Easy in and easy out. Mountain Safety Research Snowshoes (MSR) The MSR Lightning Ascent is MSR's top of the line snowshoe. I really like how they attach the decking to the snowshoe frame. It is attached all within the snowshoe frame. None of the decking wraps around the exterior of the frame. Wrap-around decking can be a wear point but there is no such concern with the Lightning. The Lightning's frame is also a huge part of the snowshoes traction. Along both sides of the frame, teeth have been cut into the metal creating very secure traction. The traction frame also helps when you are traversing a side slope. This snowshoe resists slipping and sliding downhill away from you. MSR's new binding design incorporates a plastic mesh that wraps around your forefoot. Two side straps will snub your boot into place along with a traditional heel strap. Very effective and comfortable. These are just a few of the snowshoe features and highlights from three excellent snowshoe manufactures. You won't go wrong choosing a snowshoe from any of these reliable companies. Winter in Rocky Mountain National Park has so much to offer. It would be a shame not to experience it and with a pair of snowshoes you will want to go, and often.  Murray Selleck moved to Colorado in 1978. In the early 80’s he split his time working winters in a ski shop in Steamboat Springs and his summers guiding on the Arkansas River. His career in the specialty outdoor industry has continued for over 30 years. Needless to say, he has witnessed decades of change in outdoor equipment and clothing. Steamboat Springs continues to be home. Guest submission by Nevin Dubinski As someone who has spent nearly his entire life in Missouri, visiting the Rockies is a treat. As we were growing up, my parents would take us west once every year or two and each time, I would learn to love it more. But of course my view of the mountains was insular, only visiting during the summer months and omitting the harsh winters that I heard so much about. I began to dream of reaching the peaks once the snow had fallen and I could partake in even wilder adventures. After years of dreaming my opportunity finally came this December when my friend Nick and I realized our finals week was free of exams. We rushed to complete what work we did have and hit the road on Monday, Dec. 13. The only unfortunate thing about the excursion was that it wouldn't technically be winter. The plan was to spend three nights near Black Lake in the backcountry of RMNP off of Glacier Gorge trailhead. The prospect of a Park free of timed-entry permits and camping fees was enough to make me reconsider my rule of sticking to less-visited National Forests and wilderness areas. On top of the solitude, the trip would only be 11 miles round trip, a distance Nick and I figured we would handle easily. Nevertheless, we knew we only had a few days to get everything together. We vacuum-sealed our own backpacking food, waterproofed nearly everything and solicited gear donations from friends and family. We needed snowshoes, thicker pants, better trekking poles and dozens of smaller things for a cold weather experience. By the end of it, at least eight people from both Colorado and Missouri had contributed to the cause. On Tuesday we reached the wilderness office at Beaver Meadows to some surprise from the staff. The lady behind the counter inspected us like the out-of-towners we were, bright-eyed and oblivious to what was to come. We assured her that we had all the necessary equipment to be a little less than miserable on our expedition and she reluctantly filled in our permit. That night we slept at the trailhead in our minivan, excited to hit the trail as early as possible. We woke up to a calm yet uneasy scene. The sky was tinted a soft pink and the sun was nowhere to be seen. Not ten minutes later the wind storm came in. 100-mph gusts jostled the van in a way only comparable to a hurricane. Walking to the bathroom involved leaning as if the world were tilting beneath me. We later found out that this same storm blew through Kansas with such severity that they shut down sections of I-70. Knowing that setting up a tent in triple-digit gusts would prove impossible, we decided to wait until the next morning to depart. Much to my dismay, the only time we left the van was for a short walk to Alberta Falls, about .6 miles up the trail. This short hike was our first official introduction to the Rockies’ mean side. The wind spat snow at us, temperatures sat well below freezing and the sky remained ominously gray. On Thursday we finally hit the trails, loaded down and elated by the near tropical weather. The sun beat down and brought new life to our steps. A few early risers had forged a clear run for us and we moved with relative speed given our weight. Aside from Nick occasionally complaining of cold fingers, we made it the 2.5 miles to Mills Lake without a hitch. We ate lunch overlooking the vast stretch of ice but didn't hang around for too long. A late start meant the sun was already retreating behind Thatchtop Mountain to the west. The trail past Mills and Jewel Lakes was non-existent, leaving us with the tough task of wading through deep cover. Hiking across the frozen lakes saved us tremendous time, but reaching the final junction before Black Lake was slow moving and brutal. When we finally did reach it the sign said just 1.2 miles further. The canyon began to narrow dramatically after this but we made it only .3 of a mile before we called it a day. Everything past the lower lakes was a mix of up and down, leaving us exhausted after six hours of uphill progress. Our camp was together by 3:30 pm, just in time for the sun to disappear and the temperatures to drop dramatically. We spent the rest of the night in the tent recounting the day and its scenery. When I went to scoop a bit more snow for boiling I witnessed one of my favorite views. The moon shone brightly against the surrounding walls and the gorge made no noise. They rose like blue giants in the light, still visible enough to count the trees on their ledges. It was surreal for such a vast place to be so quiet. As night wore on we listened to the wind pick up and screech overhead. Thankfully we were protected in our gully a few dozen yards off the trail. Large flakes came down in force, rhythmically striking the rainfly and lulling me to sleep at an early hour. The next bit of excitement came at 1:30am when I was awoken by a firm shake. Nick whispered at a near undetectable volume that something was outside the tent. I listened intently, and in between the symphony of falling snow I heard the distinctive crunch of snow, accompanied by the sound of sniffing. Nick white- knuckled his bear spray while I gripped my knife, and before too long we heard it lumber back into the night. The next morning we were greeted with several inches of fresh snow, covering any sign of the visitor. Everything was frozen solid from my contact solution to my underwear. Nick looked at me in protest and said he was ready to leave. I said he was free to leave whenever he liked, not unlike a pirate telling his captive he was free to go for a swim. I was going to see Black Lake at least once, even if it meant hiking the last mile alone. I strapped on my snowshoes and packed light. Only a few tools and some emergency supplies made the cut. The half liter of water I brought ended up being useless as the cap froze shut in the single-digit temperatures. While I was preparing another snowshoer passed our site headed for the lake, but returned just 20 minutes later to proclaim that his toes were going cold. He warned of deep drifts and unforgiving winds about a quarter-mile short of the lake. Nevertheless he said I should give it a run given my determined look. I took off up the hill, following the path he had cut for me. It became immediately clear that our early stop the night before had been the right call. The final mile was a grueling marathon through knee-deep snow while gaining several hundred feet in elevation. It took me half an hour to reach the obstacle the man had been referring to. His tracks ended at the base of a 60 degree slope, barren of anything but two feet of powder. In my first attempt I tried a direct approach, but was turned back by the impossible grade and fresh powder. I quickly reevaluated and decided to take the longer route around its edge which angled at a mere 45 degrees. After fighting it for nearly 20 minutes I knew I was in the home stretch when I reached the top. The trees broke in the distance and McHenry's Peak began to fill my southern view. My arrival was imminent. The only trail marker left was frozen Glacier Creek, which I would soon learn was not so frozen. The final pitch was Ribbon Falls, a meandering stretch of ice just below the lake which served as a perfect beginner climb. I dumped my bag and snowshoes just before the falls and made my way up the frozen slope with my ice axe and crampons. Within minutes I was making my way through the waist-deep snow on the banks of Black Lake. There was no evidence of humans, no animal tracks, or even a plane overhead. It was just the mountains and I. Directly across the lake was the largest column of ice I had ever seen, an uninterrupted sheet that traveled the final thousand feet to Frozen Lake. Sitting there in the snow I couldn't help but wonder how I might traverse it. Unfortunately I had told Nick I would be back within the hour. I said goodbye to Black Lake, confident I was the only person to have visited it that day. As I negotiated my way back down Ribbon Falls, my foot plunged into a free flowing section of the creek that had hidden itself under a foot of snow. My foot stayed dry but the slushy mix instantly welded my crampon to my boot in a bond that proved nearly impossible to break. Aside from this misstep I made my way back down the creek without incident, exuberant that I had witnessed such a beautiful view in solitude. When I reached the tent I informed Nick that he was no longer being held against his will. He had told me that morning that he had seen everything he needed for that trip, and after my final trek I was inclined to agree. We quickly packed and made our way back down to Jewel Lake. As we rounded the switchbacks near Alberta Falls in the final mile, a full moon stood proudly over Estes Park, accented by the pink and blue gradient of a Colorado sunset. The trip was one of setbacks and learning experiences, but we still managed to persevere long enough for at least one of the three nights I had hoped for. Nick and I found joy in even the fiercest conditions and I fulfilled a lifelong dream in the process. Although Nick may have been scared off for a bit, and rightly so, I'm certain I'll be back for far greater challenges in the future. Despite my inexperience I can confidently say this: Those looking for a slice of isolation should know even the most popular trailheads can offer a unique and unmolested experience come winter.

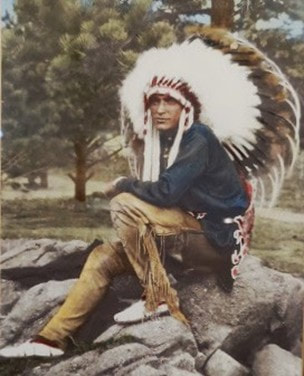

The key to staying warm is staying dry! story and photos by Murray Selleck, HIKE ROCKY’s equipment specialist Note: these recommendations were not solicited and we receive no financial consideration from any of the manufacturers mentioned I remember a particular winter backcountry ski day like it was yesterday. Even with decades of time having passed, that single drip of sweat running down my side left an impression. We were backcountry skiing and hiking for turns when it happened. These were the early days when layering for warmth was becoming more technical with the fabrics being offered and fast becoming a widely adhered to concept. Of course, layering for warmth has long been an acknowledged practice. Think Shakelton and the Endurance. Think Charlie Brown on the baseball mound so thickly layered up he can barely move! The reason why I remember this specific backcountry ski day so well is realizing my next to skin wicking layer was certainly not wicking, far from it. Ideally, the layering concept is designed to allow the sweat and perspiration you generate while skiing or snowshoeing or any high aerobic activity to wick off your skin and pass through your insulation layer. Layering correctly will prevent you from overheating while keeping you warm and dry. On that particular winter day, with sweat sending shivers up my back, was a huge fail. Since then, through lots of trial and error, I wear a layering system that works really well for myself. However, it goes without saying that what works and feels comfortable for one person doesn't mean it will be equally effective or comfortable for the next. But here are a few ideas to keep in mind as you dress for your next hike, winter ski, or snowshoe day in Rocky Mountain National Park. The key to staying warm in winter is to stay dry. This means your next-to-skin layer is truly the most essential. It must wick the moisture off your skin. This layer should also be quick drying. It shouldn't stay damp against your skin. If this first layer does stay damp you will have to use even more energy to stay warm. As soon as you pause for a break to catch your breath or take a drink of water you'll start to chill down. Your break will be short lived because you'll have to quickly get moving again to regenerate more heat to overcome your chill. A frustrating repetition of sweat, chill, warm up, sweat, chill, warm up will repeat itself all day long. This first layer, the next to skin base layer, is critical to keeping yourself dry, warm, and comfortable even in the most extreme temperatures. The best way to ensure that your next to skin layer works properly is to have it form-fitting to your body. Some manufacturers call this body mapping. The layer shouldn't be loose, baggy, or floppy anywhere on your torso or legs. Body mapping tops typically have specific areas within the design to vent more heat or be purposefully even more snug fitting than the rest of the garment. This was the biggest lesson I learned during that winter ski day way back when. How was my base layer supposed to wick when it wasn't even touching my upper body in all places? Once I began wearing body hugging, snug, form fitting tops and bottoms did the wicking performance actually begin to work effectively. This snug body hugging-fit may feel pretty foreign to lots of first time users. However, once you get use to the feel you'll never go back. Think of the next to skin layer's sole purpose as transporting moisture off your skin or wicking. This is what will keep you dry... and comfortable. Don't think of this layer as an insulating layer. The most effective wicking layers I have found are also incredibly thin as well as body hugging. Since they are thin that also makes them very quick drying. During a ski or snowshoe break this layer is drying equally as quick as it is wicking moving all that underneath “micro climate” generated moisture away from my skin. I can enjoy a satisfying drink of water and snack without feeling rushed or compromised by the cold temperatures. Here are a few of the next-to-skin tops and leggings I have found to be really effective. I use one or another pretty much every winter day Nordic skiing or snowshoeing. Craft Active Extreme X (Sweden) Craft was the first top with a body snug fit that I ever wore. It was my game changer. The Active Extreme Top is made with 100% recycled polyester, much of it from old fishing nets. Mesh inserts under the arms to promote ventilation, flat lock seams and stretchable material for easy mobility, waffle knit design for enhanced wicking... these are the things that make up a wonderful next-to- skin layer. By the way, that first Craft top I wore many moons ago? I still have it and wear it on certain trips which speaks to the durability, performance, and longevity of Craft products. Bjorn Daehlie Compete-Tech (Norway) For those who may not know, Bjorn Daehle, is the most successful male cross-country skier in history. He and his clothing company know a few things about how to stay warm and dry outside in winter. The Compete-Tech top is the thinnest top that BD produces. The lightweight fabric and snug fit will keep you dry no matter how fast you climb or how long you stay out. The fabric is made with Tencel, recycled polyester, and fine merino wool. Tencel is produced from fiber extracted from cellulose pulp from sustainable, fast growing eucalyptus trees. Ortovox Comp 120 (Germany/Switzerland) This is another very light next to skin layer. The fabric make-up is 70 % virgin wool for wicking and warmth and 30% polyamide to provide the snug body hugging fit. Ortovox uses a unique circular knitting technique which creates a practically seamless garment. This weave also allows Ortovox to create body mapping zones for strength and increased breathability. Ortovox uses merino wool from Tasmania for their next to skin fabrics. They also use Swiss wool for increased insulation in their midlayers and outer jackets and tops. Ortovox takes pride in knowing exactly from which farms their wool is produced ensuring quality and animal welfare. Odlo Active F-Dry Light Top (Norway) Yes, there is a theme here... Scandinavian companies offering body snug, exceptional wicking and fast drying garments. The Odlo F-Dry Light top is made with 88% recycled polyester and 12% recycled polypropylene. Odlo produces a variety of fabrics for their base layers including sheep's wool and yak wool. There are many more companies producing great next- to-skin base layers. The choices are practically endless. Swix, Smartwool, The North Face, Icebreaker, Helly Hansen, and on and on... The trick is to find a company you believe in. One that you can support both with your dollars, trust, and recommendations. The great debate over next-to-skin fabrics that is synthetic materials vs natural (primarily wool) and renewable materials, won't go away anytime soon. Everyone will develop their personal favorites. Early on my choice was always synthetics. There was no comparison when it came to synthetic materials being faster wicking and drying. Wool users countered with the fact that it is a natural and renewable resource. It doesn't pick up or retain body odor. Wool is also an excellent material at wicking. They just couldn't claim it to be faster drying or produce a body hugging fit. Durability was also an early issue. Today, much of those old arguments have disappeared. Synthetics are being manufactured with recycled materials and have added anti-microbial treatments to eliminate funk. Many of these same manufacturers who primarily produced synthetic layers have also added wool options to their product lines. And, many manufacturers producing products with wool are using core spun (synthetic fibers combined with wool fibers) fabrics to their clothing to achieve a body snug fit, enhance the drying effect, and increase the durability in high wear areas like around your shoulders because of backpack straps. The choice between synthetic or wool as your next-to- skin layers will always come down to a person's perceived comfort, performance expectations, and metabolism (which in of itself is another whole discussion). The one constant remains... to stay warm in the winter backcountry you have to stay dry!  Murray Selleck moved to Colorado in 1978. In the early 1980s he split his time working winters in a ski shop in Steamboat Springs and summers guiding on the Arkansas River. His career in the specialty outdoor industry has continued for more than 30 years. Needless to say, he has witnessed decades of change in outdoor equipment and clothing. Steamboat Springs continues to be home. Simon Vogt's vlogs of his summit of Longs Peak in September, 2021, and above Dream Lake earlier this year. story by Barb Boyer Buck, photos & videos by Simon Vogt Colorado resident Simon Vogt has summited 57 of the state's 14-ers (mountains over 14,000 feet in elevation); he only has one left: Culebra Peak in the Sangre de Cristo range. Mountaineering in the high peaks of Colorado's Rocky Mountains has become a metaphor for the new life he is developing for himself: one of sobriety and focus. “The summit is the goal, but it's not the reason,” he said. Since choosing sobriety three years ago, Simon has turned to high places of Colorado (and other states) for solace and a sense of accomplishment. This attitude hasn't been Simon's strategy his entire life, however. He was born and lived in Germany for eight years after which his family moved to New York. He moved to Colorado for college in the early 1990s. “Colorado is the first place I developed a real interaction with the outdoor world: climbing, hiking, and mountain biking,” he said. But he also encountered tumultuous problems with the law, alcohol, and drugs. His naturally impulsive and reckless nature got him into some real trouble while he was using and drinking. “I almost died many times,” he said citing a week-long coma from a heroin overdose in 1994 and daring mishaps while bouldering with friends. “I was also shot at several times and stabbed as a result of poor choices,” he said. “It was the world I was living in at the time.” A couple of years after that, he almost died again. “I quit drinking after I went to the emergency room for pancreatitis. It felt like I was on my deathbed.,” he said. “Being able to get up from that bed and walk out of the hospital was the beginning of a new start, and a miracle.” He faced an immediate test right after getting sober; his boss died, he got evicted from his apartment, and his girlfriend left him. He started living in his truck. In those uncertain days, Simon started taking walks at night because he couldn't sleep. “I got back into hiking more and more after that,” he said. Simon likes to hike alone, especially on his longer adventures, but takes care to be sure he is prepared. His naturally impulsive personality no longer turns reckless, as he cares for his well-being now. He pushes his limits, but he doesn't exceed them. “It's nice to be alone, but running into someone is reassuring,” he said about seeing others on the trail. “It's a secret link between you and them, a camaraderie of being with someone within a 10-mile radius. “ “Mountaineering is very peaceful, meditative, and an inner experience,” he said. “There's a dichotomy between being deep inside of yourself, examining your consciousness from a little further back in your mind, juxtaposed with the physical challenges of the outside environment. “Emotionally, it puts me very much at ease, I go out there for the feeling of solitude, to get more of an inner connection by having that outward experience. This is when I thrive and feel alive.” On his adventures, Simon also finds he can communicate quite easily with what he understands as God; this has been one of his touchstones since achieving sobriety. “Turning your life over to a higher power, trusting that things are going to be OK, any way it turns out-- that is the key,” he said. “You have to let things go and not stress or be anxious about things you don't have any control over, like trail conditions or the weather, or what you encounter at work. “Once you see yourself as connected to a greater path in life it's easier to enjoy the moment.” The gratitude he feels while on these trips reinforces this connection. Suddenly, he is no longer the outcast and trying to fit himself into a shape society asks him to fill. These days, Simon works as a freelance contractor and carves out considerable time for traveling and mountaineering. While standing on these mountaintops alone, he sees these moments as wonderful gifts that are uniquely for him. “I experience a rush of endorphins, that weird chemical euphoria that I used to seek out artificially,” he explained. “I become grateful for being a human on this planet, for having legs to get me to the summit.”

Simon is continuously honing his preparation for hiking; after every trip he has figured out a way to lighten his pack a bit more and reduce the amount of water he carries. “When climbing a mountain, you should only expend about ¾ of your energy climbing to the summit, you need to reserve about ¼ for the return,” he counseled. “You need to find your own path and whatever path that is, keep moving. Keep moving even if it's not forward, sometimes you have to go sideways. As long as you keep going – take another step and then another and another. “I apply the same things in hiking that I apply in recovery; it's not necessarily getting to the mountain top that's the important thing. In life, you're never like 'I made it!' You never truly reach that point. You're never done, it's never over. Once you get to the top you have to get back down.” Taking responsibility for his actions, along with expecting setbacks on the journey is essential to Simon's new outlook on life. “If you can use those setbacks and disappointments not as a discouragement but as a motivator, you succeed,” he said. “They are learning experiences and that's what it takes to improve. You have to expect to have problems and run into unforeseen things – in life and in hiking.” story, photos, and video by Jason Miller I have hiked up to Gem Lake via Lumpy Ridge Trailhead many times in the past years and highly recommend doing it. This time, we started deep within the McGraw Ranch and ended up at this iconic spot atop of Lumpy Ridge. We came across grasslands, rivers, forest, mountains, but very few people. This hike is a MUST DO! We began the morning with my son driving his car and me following behind him. We parked his car at the parking lot of Twin Owls and Gem Lake Trailheads. We then took a picture of our beginning point and jumped in my car to head toward McGraw Ranch. We got mentally prepared for our adventure of the day with a little coffee, breakfast snack, and some good music. Music, It does the soul some good. When pulling onto McGraw Ranch Road, realize that this is a residential area and that these are private homes. Drive slowly and respect the area residents that call this home. The parking area is located 2 miles from Devils Gulch Road. and is located at the end of the road alongside in designated areas. Once parked, we were on our way. The old McGraw Guest Ranch is located at the trailhead. There used to be 25 buildings and five of those dated back to 1884. This opened as a dude ranch in 1936 for the enthusiastic adventurist. It specialized in trail rides, fishing, cookouts, and even square dancing. We walked past a few old buildings where all the fun used to be had and started down the trail. It starts off as an easygoing, flat hike. Vast, grassy meadows all around you remind you of the fall wildflower beauty. After walking through 1.2 miles of the grasslands you come to a fork in the trail. If you would go right, it takes you to Bridal Veil Falls (2 mi) or Lawn Lake (8 mi). We chose to go left. Gem Lake is 2.8 miles ahead. Jakob's car is 4.5 miles. From here it gets a little more challenging. We traversed downhill a little and crossed a river. I love crossing on the cut logs, makes me feel like a kid. Crossing the river means that the incline begins. Heart pumping and legs burning are normal for me. I have hiked up to Gem Lake many times but not on this trail. During this awesome time in the wilderness, you will experience all sorts of terrain from large meadows to heavily populated forest areas. I have always wanted to go on this trail, and it is super serene. There is not major rock scrambling on this hike, but the listed elevation gains and losses do not do it justice. There are a lot of ups and downs. After 1.5 hours of speed walking, we made it to Gem Lake. This is the first time we have seen people today. It is a small lake at the top of Lumpy Ridge surrounded by large boulders and rocks. I could not see any fish in it but if you are going to fish in the RMNP, make sure to read up on rules: have a fishing license and catch and release. Please help our fish population. There are great shady areas all around the lake to find a nice resting area. We sat down to eat lunch and drink some water. After 15 minutes, we continued down the mountain. It is 1.8 miles to the parking lot. Not too long after we started our descent, we came across a privy. If you need to use the toilet in the wilderness this is one of the best views out there. Traversing down a little farther and we came to Paul Bunyan's Boot: a large rock feature that looks like a boot with a hole in it. A polaroid moment. Many different spots on the way down proved to be great photo spots. Views of the snowcapped Rockies and the Estes Valley in the distance make for another spectacular photo. Some people enjoy hiking in silence, others find it enjoyable to wear headphones; whatever you like just make sure that you do not create noise pollution. Please don't carry in a boom box. We made it down to the Gem Lake trailhead within 3 hours of starting the hike. When I hike with my son, he tends to walk faster as we go farther. I highly recommend getting outside with family and friends. It is a great time to catch up on life challenges and reconnect with your loved ones. Sometimes just being together in silence is one of the best feelings in the world. Remember this time of year to dress in layers. It may start off cold but could turn warm and end up cold again. GET OUTSIDE!  Jason Miller, 49, is a resident of Glen Haven and is married with two children. Before moving to the area, he used to work as broker for Nestle USA and H.P. Hood milk company. Today, he is the owner of The Rustic Acre (vacation rentals in Estes Park) and co-owner of Lightbrush Projections. One Northern Cheyenne woman's perspective on life by Barb Boyer Buck Just a few minutes south of Estes Park, there is a remarkable place redolent with various traditions and history, both native and non-native. Eagle Plume's Trading Post, just over the Boulder County line on Highway 7, is owned by Nico Strange Owl, who took over the full operation after the recent deaths of her parents. Her father, Dayton Raben, passed last December of a stroke and her mother, Ann Strange Owl, lost her battle with Alzheimer's in July. Nico sat down with me last week to speak about the history of the place and her perspective on the traditions which formed her life. To'tseha (The History of of Eagle Plumes) The building itself was built in 1917. It was originally commissioned to look like a Kansas farmhouse by Katherine Lindsay who wanted to open an inn in the proposed town of Hewes-Kirkwood, slated to be developed in the area. Lindsay was an artist and painter in an early art-deco style; she opened the What Not Inn and decorated the establishment with her artwork and beadwork her father “collected” during in the Indian Wars in Kansas. The building next store was the grocery store.  Intricate beadwork is part of Eagle Plume's collection. Intricate beadwork is part of Eagle Plume's collection. After a few years, she realized there was not going to be a town; business was very seasonal and most people were heading to Estes Park or into the national park itself for their lodging needs. She had married a man named Perkins and they turned the inn into a trading post dealing in Native American art from the early to mid-1920s. Her husband was sickly and passed away soon after, so she hired Charles Eagle Plume in the mid-1930s. “He showed up on horseback one day,” said Nico, “and claimed to be one-quarter Blackfoot Indian from Montana. “He was a master marketer; he ran the place and made it famous. He would dress up in Native American regalia and pretend to shoot arrows at the passing cars and then point them toward the store.” Works purchased from Mrs. Perkins and Charles are housed in museum collections, including the Denver Art Museum.  Charles Eagle Plume as a young man Charles Eagle Plume as a young man “Together Charles and Mrs. Perkins built on their collection; they were close, he became like a son,” Nico said. “When she passed away in 1966, she left the store to Charles.” He was adamant about carrying only Native American-made art and goods. This holds true today, except for a line that is designed by Native Americans and made elsewhere. “In the beginning, we could find things to offer that were $5-$10, but not anymore. We carry these to be competitive,” Nico explained. Nico's parents moved to northern Colorado in 1966, when Dayton got a job as a history teacher in Berthoud. “When they got married, interracial marriage was illegal in Wyoming. He was a white man of German and Scots descent from that state, and she was a Cheyenne woman, working on the Wind River reservation. He fell in love with her right way; they were married within three months of meeting,” said Nico.  Dayton Raben and Ann Strange Owl Dayton Raben and Ann Strange Owl “When dad took mom to meet his family, some of them tried to buy her off to get the marriage annulled; they were horrified he had married a native woman. When mom introduced him to her family at her home in the Northern Cheyenne Reservation in Montana, some stared right through him as a sign of banishment,” Nico said. On the advice of his father, the couple moved to California where Nico was born. For the sake of the child, they wanted to get closer to family – “but not too close!” Nico said, which precipitated the move to Colorado. There were frequent trips to the reservation where Ann had lived, but she was feeling lonely for other native people in Colorado. She had an aunt who was southern Cheyenne; this woman lived in Denver because of the government's efforts to assimilate Native Americans into larger cities. "They were trying to take them away  Nico Strange Owl Nico Strange Owl from the native language and culture,” Nico said. Ann didn't feel at home with the Denver Indian community, so someone told them to visit Charlie at Eagle Plume's. “Charlie loved mom right away, he loved native people. He asked her to work for him at the trading post,” said Nico. He kept hounding her until she finally said yes in 1979. “They became really good friends and Charlie adopted mom in the native plains tradition.” In native plains tradition, a person can adopt another (even if they are not related by birth) by exchanging gifts, Nico explained. “Charlie gave her a Cheyenne dress with beaded boots; he made posters to sell from a photograph with her in that dress.” While Ann started working for Charlie in the summers, Dayton would come up and sit behind the shop and read books or take walks. Finally, Dayton was persuaded to work in the shop, too. He would regale the male customers with stories about the weapons in the collection while the women shopped, remembered Nico. Nico began working at the shop when she was getting her degree in Anthropology from Colorado State University. She would come up in the summer, sometimes with friends from college, to work (and nap!) in the shop. ”After a hard night out the day before, "We took turns taking naps up there." “When Charles caught us, he got very mad and made us fold the rugs. That was a horrible job,” she said. “Charles didn't have any children, so he created a buy/sell agreement with my parents, the bookkeeper, and the sales lady,” Nico explained. Immediately after Charles’ death in 1992, the bookkeeper and sales lady broke the agreement and put the store up for sale. “That was a horrible summer,” said Nico. “The sales lady was really prejudiced against Indians and Charles would defend my mom against her all the time.” But now he was gone, and two of the three members of agreement were trying to sell the shop. Nico recalls that through the summer, they hadn't really gotten any offers and curiously, the sales lady began declining in health rapidly; she had kyphosis - an exaggerated, forward-rounding of the back. One day, the bookkeeper came in and said she had changed her mind about selling. Why was that? Well, reported Nico, the bookkeeper had a dream where “Charles came to her, and he wasn’t happy” about the proposed sale. In 1993, the other two women were bought out by Nico's parents, who went on to run the store for the next 30 years with Nico's help. “it's funny, because Charles ran the place for 30 years before my parents got it,” Nico recalled, “and Mrs. Perkins ran it for 30 years before she went into a nursing home. “Before Charles passed away, I was packing up the collection at the end of the year to put it in storage while he gave instructions from his wheelchair. He looked at me and said, 'My dear, one day you will have a son and he will run this store.' I have one son but he doesn't want to run the store like it has been, so we'll see if it comes true.” Perhaps Nico has to run it for 30 years first? Nico was very close with her parents, and Charles. Charles helped get Nico her first job after college, at an Indian art gallery in Vail. “There was a couple that had an Indian shop in Vail and came in and asked Charles if they could consign his stuff for the winter (since Eagle Plume's was only open from mid-May to mid- September).” Charles pointed at Nico and said, “she has to be part of the deal. because he knew she wanted to ski. “So I went and managed their gallery and sold his stock so he could replenish for the next summer. It was crazy how much stuff he had.” So Nico skied, mountain biked, and sold Indian art in Vail for the next seven years. Then, she got married and moved to Denver where she put her now-ex through graduate school. After the divorce, Nico came back to run the store with her parents after Charles died. “We ran it for decades, and I miss them so much,” she said, “but I always knew they would go together, they were so close. After my father died, I had to retell my mother multiple times a day that he had passed,” Ann's Alzheimer's was taking control. “Every time, she would cry and mourn, it was terrible.” Finally in March, it sunk in her husband was gone, said Nico, and then Ann deteriorated quickly. “So now, it's just me and Kay (the current sales person), my son, and a few neighbors who come in and help; it's good,” said Nico. -tsėhésevo'ėstanéheve (to live as a Cheyenne) Today, Nico honors her father by telling his stories to people who come into the store and she honors her mother by trying to be a “good Cheyenne woman.” “What does it mean to be a good Cheyenne woman?” I asked her. “Well, I'm not a great Cheyenne woman,” she laughed, “but I try.” A good Cheyenne woman works hard and keeps her place very clean and organized, Nico said. " To be humble, respect your elders and take care of family and community. “ This is what we teach our children: you have two little eyes to see, two little ears to hear, and two little nostrils to smell with but you have only one mouth. You must listen more than you talk. I try to do that,” she said. “People used to come in and say 'Wow, your mom is so quiet, so regal,' but she was just being who she was, a good Cheyenne woman. Nico explained she herself is just one Cheyenne woman and can't speak for the Nation but through stories told by her relatives and on the reservation, she has created her life to carry on certain traditions. One of the things that is quite important to her is the Cheyenne language, and how names are given. “So, having 'Strange Owl‘ as a last name was because of the government,” she explained. The original Strange Owl was her great-grandfather and when her ancestors were put on the reservation in Montana, they decided that all of his nuclear family would have “Strange Owl” as their last name. “They gave him the first name of John,” she said. Her great-grandmother's name was Turtle Ribs, but was given the name “Mary,” so she became Mary Strange Owl. Nico's real name is Appearing Buffalo Woman, “a buffalo transforming into a woman,” she explained – in Cheyenne, it's spelled Esevonenameh'ne'. Original names are what are used among her Nation, between each other, she said. Her son's name is Dah'som, the name of a grandfather on the reservation her mother grew up with who was very light-hearted, funny, and loved to make people laugh. But in order to use that name, her mother had to get permission to do so. She had to give a reason and, in this case, it was because she honored the grandfather and wanted his traits to be part of Dah'som's life and persona. “You can only give a name four times,” Nico explained. For example, her mother's name was Blue Wing and she gave it away three times, but then her mother gave it away a fourth time. “She was really mad her mother did that, so she gave her own name (which means she needed another) to my granddaughter,” said Nico. Nico spends as much time as she can with the youngest Blue Wing, teaching her Cheyenne language and customs. Ann's new name was Medicine Eagle Feather Woman, “which she didn't like,” said Nico. “She thought it was too long.” Preserving the Cheyenne language is very important. A Cheyenne prophet, Sweet Medicine, who had many predictions that came true, said that when the Cheyenne lost their language, “a yellow-toothed monster would eat the world,” Nico said. She was concerned when the renaming of a mountain in Colorado from its English name - which was derogatory and sexist - to the Cheyenne name for Owl Woman: Mestaa'ėhehe (pronounced mess-taw-HAY) was criticized by the governor. Polis thought it was “too hard to pronounce,” and initially objected to it. Recently, he agreed to the name but warned against using hard-to-pronounce names in the future, arguing it would make people revert back to the original, offensive name it was trying to remedy. The Cheyenne etiquette can be interpreted as opposite of mainstream etiquette, she said. White people are called vé'ho'e, meaning spider, because they wore woven clothes (like a spider's web) and/or because they carved up the land with fences, rail lines, and farms. Unlike the vé'ho'e, in the Cheyenne Nation, you are considered most honorable if you give things away and if you own very little possessions. For example, when Nico and her cousin came of age, their grandmother on the reservation honored them by buying a buffalo and taught the girls how to clean and dress the entire animal. Being young, they tried to take a short cut by putting a garden hose through the intestine which made it flop all over the place. “My grandmother was very angry about that,” remembered Nico. Every part of the bison was used; the tendon that run from the shoulder to the tail along the back was made into sinew, thread for jewelry making. The hide was tanned. There were strips of meat cut and dried; the bones were preserved for carvings. And every bit of the meat was given away. This brought great honor to the two girls, who were learning what it meant to be Cheyenne women. “Every part of the animal is used,” Nico explained; there is no waste. The animal was thanked for the high honor of providing its life for the sustenance of others. “I hunt and I always thank the animal for its life,” she said. “I think all hunters do that – it's instinctual; it's a powerful moment when an animal dies while you are there. “We have a long history with the Earth; our creation story speaks of the Creator asking a bird to find him some land because there was nothing but water, so the bird dove down and brought up mud. The Creator then turned that little piece of mud into land. The earth is miraculous and precious,” Nico said. She was taught about the plants that act as medicines and how you should only take what you need and leave the rest. “You never pull up sage from the roots,” she says about the sage that grows around Eagle Plumes. She uses the sage to pray herself, greeting the sun each day. There are greens and mushrooms that can be eaten in the area, and there used to be thimble berries (tiny raspberries) that grew all over the site where Eagle Plume's sits, even moss on the trees. Global warming has changed a lot of that, she said. The area in and around Rocky Mountain National Park was part of the Cheyenne's culture, providing sustenance and ceremonial sites; they came up from their land east of the foothills and north of Denver to hunt, gather berries in the canyons, and worship. Lodgepole pines from the Tahosa Valley where Eagle Plume's sits were also used. “This land around here is part of my genetic heritage,” said Nico, “it's not a mistake that I am here.” There's something about Eagle Plume's, Nico Strange Owl (Esevonenameh'ne'), and the traditions she is trying to preserve that make me stop and think. What would it be like if everyone in the world would give more than they take, if you could create family by giving gifts, and if everyone fully understood the ramifications of disrespecting the land they live on? This article was published in the November 2021 edition of HIKE ROCKY magazine.  Barb Boyer Buck is a professional writer, journalist, editor, photographer, playwright, and researcher who lives in Estes Park. Barb is the managing editor of HIKE ROCKY online magazine. |

Categories

All

|

© Copyright 2025 Barefoot Publications, All Rights Reserved