|

Notes from the

Trail |

0 Comments

By Rebecca Detterline The fall colors were not quite popping on my recent trip to the Thunder Lake Cabin, so as I stumbled happily around Wild Basin, I began to take notice of all the wild flowers transitioning into their autumn expressions. As we await the peak of fall colors, we tend to forget the wildflowers, assuming they are ‘done’ for the season. What if the wildflowers are not done? What if they are just now taking their truest, most beautiful form? Maybe wildflowers are like humans in that they do not become their most genuine selves until they have weathered a few storms.

‘No spring or summer beauty hath such grace as I have seen in one autumnal face.’ -John Donne The Mountains Have Seen it All

By Sybil Barnes There’s a saying you might have heard - “The only thing constant is change.” Sometimes I wonder how true that is. When I look up at Longs Peak or Twin Owls or the thumb on Prospect, I can imagine that I’m Patsey Estes or Isabella Bird or Esther Burnell seeing them for the first time. There are many other places in Estes Park and Rocky Mountain National Park about which I can’t say the same. But aside from a radical change in population of both visitors and residents and the associated buildings, roads, and services that go along with that increase, what changes have truly happened here? Let’s start with some of the history we know. Perhaps as a way to escape from the turmoil of the approaching Civil War, Patsey Estes and her family chose to live a hardscrabble life of subsistence ranching in a place with no neighbors. She had followed her husband from a relatively comfortable life in Missouri to this place he had discovered on a hunting trip and thought was beautiful. As far as we know, none of her letters or other writings exist so it’s impossible to say if she shared that feeling. This open space offered sweeping views with no neighbors. Though there was an abundance of wild game and fish to eat, it was a lonely life. The Estes family only had each other and the rare visitor for entertainment. Joel and his sons made trips to Denver to sell meat and skins but Patsey was home with the other children and a million chores. They eventually moved on to New Mexico after selling their “improved” property with its panoramic views from Longs Peak to Eagle Rock. Isabella Bird shared a lot of her feelings when she arrived as one of the first tourists to enjoy the hospitality of Grif Evans and his family. Evans had only moved up the hill from Lyons to take over the Estes holdings and was one of the first to recognize the potential of entertaining visitors as a revenue source. Ms Bird had a horse and was interested in exploring the area both on horseback and on foot. As a visitor, she had few of the responsibilities of providing a home or entertainment. Her writings may have encouraged an Irish nobleman to explore this part of Colorado while he was on a hunting trip to Wyoming. Unfortunately, no known record exists of the guests at Lord Dunraven’s hotel on Fish Creek. There are a few photographs which show women “taking the air” in front of the hotel. And it is known that the Irish Earl was not accompanied by his wife or daughters on most of his American trips. He spent his days riding and hunting and his evenings with food and drink. His visits were mostly made in the summer or fall but he left a land manager here year round. By the beginning of the 20th century, there was a town forming in the open space that had been named Estes’ Park by the newspaper editor, William Byers. Ranchers like the MacGregors and the McCreerys and the James and Hondius families arrived in the later 1880s and had become used to the conveniences of a general store and weekly mail delivery. More and more dudes were discovering the delights of a summer spent in the cool mountains. Shops selling souvenir photographs were opening at the confluence of the Big Thompson and Fall River in the space between Elkhorn Lodge and the MacGregor holdings. Horses and hiking were the main means of transportation and a pleasant way to explore the area. Other families, including the Spragues and Chapmans had ventured further west and created another small community in what they called Willow Park. Private cabins were built on the eastern hillside with sweeping views of the meadow between the moraines. Fish were abundant in the Thompson River and Frank Bartholf grazed his cattle further to the south on what would become the Bear Lake Road. Flora Stanley first came to Estes Park with her husband in 1909. He saw the potential for growth and development as a summer tourist destination. He had the discretionary income to build a fine hotel and create an infrastructure of utilities for the town that had been platted by Abner Sprague and was being marketed by Loveland businessman C.H. Bond and others. The hotel needed electric lights and indoor plumbing, so Stanley funded a power plant and a sewage system which would serve the entire village. He donated some of his property for public use as a community park and gathering place. Flora had vision problems so she was unable to comment on the view. She was probably delighted that her husband’s respiratory problems were solved by spending summers in the mountains but possibly just as happy to return to Maine for nine months of the year. When Esther Burnell and her sister Elizabeth came west on a summer vacation they discovered another settlement in the Tahosa Valley at the base of Longs Peak. The young women were hired to be nature guides at Enos Mills’ lodge. After a summer spent climbing mountains and identifying wildflowers, Elizabeth went to California to continue her education and Esther stayed to homestead property on the Fall River Road. She married Enos and became the mother of Enda Mills Kiley. After Enos’ untimely death, Esther and Enda carried on his legacy by running the Longs Peak Inn and making sure that his nature writings stayed in print and his ecological philosophy was brought forward through the 20th century. Growth of the town of Estes Park has always been limited by the topography of the area. Many people wanted to visit in the summer but not that many wanted to spend a windy and cold winter here. That changed with the construction of the Adams Tunnel to bring water from the wetter west side to the plains of eastern Colorado. When Bertha Ramey’s family moved from Lyons to start providing insurance and related services to the businesses and homeowners, the land where the Estes family had settled was still a meadow with the Big Thompson River meandering through it. By 1950, that property had been flooded by a reservoir called Lake Estes. Now when visitors make the last turn down Park Hill, they see water reflecting the mountain ranges beyond. Also by the 1950s, a few hundred people had decided to spend the winter months in Estes Park. Many of them worked for the National Park Service. Others spent the slower months getting their tourist accommodations ready for the next season. By the 1970s, young business people were seeing the potential for attracting visitors all year round. Though the main business district of the town was still only three blocks long, development had reached across all the flat spaces and was beginning to creep up the sides of the surrounding mountains. Geologic time outlasts any kind of human time. And the mountains can withstand climate change more easily than any animal or plant life form. In a hundred years or a thousand years, the approaches to Estes Park and Rocky Mountain National Park will still be up from the lower elevations with a last drop to a valley surrounded by mountains. Whether your view is of Twin Sisters or Lumpy Ridge or Ypsilon or our favorite fourteener, Longs Peak, and your family has been here for four generations or you are one of the four million who visited during the last year, remember these words from a song by Cowboy Brad, who we also know as Longs Peak Ranger Brad Fitch, “We live in Paradise.” (This article appeared in a slightly different form in the Rocky Mountain Conservancy newsletter. Are you a member of the Conservancy?) ‘If I fall asleep right now, I can get four full hours of sleep before my hike across the divide tomorrow. Unfortunately, I’m still at work!’ It’s that time of year when those of us who are lucky enough to live, work and recreate in the Estes Valley are stumbling around like a bunch exhausted zombies living on a diet of coffee, craft beer, beef jerky and gummy worms.

It is the season of back-to-back 4 am wake-up calls followed by showers at the Rec Center and eight hours of slinging beers at The Rock Inn. I can’t remember the last time I sat down for a meal with my boyfriend. I think we maybe shared some bleary-eyed sips of early morning coffee earlier this week. I love the busyness of it all, especially knowing that it is the final push before we transition into fall. I’ve heard folks say that if you’re lucky enough to live in the mountains, you are lucky enough. That is certainly true and I am so grateful for my good fortune! On top of that, I have been blessed with a strong body, a (relatively) sound mind, and a job and coworkers (and customers!) who make work fun. I get to play outside almost every day. Sometimes I am not sure what I did to deserve all this and I even feel a little guilty about it. The best way I know how to thank the universe for all I’ve been given is to practice gratitude every single day and share experiences and knowledge with others. Lately I’ve noticed people declining my invitations to get outside because they feel intimidated. To me, this is hilarious and these concerns are completely unfounded. I have never considered myself an athlete. Being able to walk a long way in the mountains carrying a heavy pack does not make a person an athlete. It does make one a good candidate for manual labor, though. My late husband was a classic sandbagger, forever lowering me down ice climbs that were grades above my ability level or taking me on adventures that lasted twice as long as he remembered, causing me to show up to more than one shift at work unshowered and wearing ski pants. While I wouldn’t change a single one of those zany experiences, I am very careful to respect other people’s tolerances for risk and suffering. For me, getting out into the mountains with someone is about the time spent with that person. Whether we are going across the continental divide, up Longs Peak or walking to Mills Lake, time in the mountains is for sharing laughter, stories and sometimes tears. It is certainly not about getting to some destination I have likely visited many times before that will still be there next week or even next year. All that being said, I am so grateful for the amazing adventure partners who have helped me expand my comfort zone. I, too, love seeing people push themselves beyond what they believed they could do. Let’s all continue to encourage one another to reach new heights while respecting boundaries, limitations and fears. Cheers to the end of another great season and to the memories made and friendships strengthened as we continue to navigate the peaks and valleys of this beautiful life. Early Estes Park - A Search for Opportunity

By Sybil Barnes This is a forward I wrote for a section of a 2007 publication featuring the photographs of James Frank. The library still has a couple copies or you might be able to find it on a used book site. “Magic in the Mountains: Estes Park, Colorado.” JJ has had a varied career in Estes as a musician, extraordinary photographer, author, purveyor of First Light postcards, and the original owner with his wife Tamara of the Aspen and Evergreen Gallery. Another major contributor to this book was Paul Firnhaber and several other local “celebrities” wrote introductory forwards to various sections. I’ve made a few minor changes to to the original text: History is how we keep track of our memories. Because few of us can interpret the cry of the hawk or the chitter of a chipmunk or the song of a waterfall, and fewer can even hear the voices of rock or tree, our history is told through human vocabulary. We use our personal experience and recollections of experiences handed down through generations of the people who live in our town to place an order and possible meaning on what may be random events. History is the story of a search for opportunity. The earliest opportunists who came to this area were the people we now identify as PaleoIndians. These nomadic people enjoyed the abundance of wild game and respite from the heat of summer on the high plains. Even then it was a transitory experience. Not many were willing to spend the winters in a place they called “the land of many snows. As civilization and settlers moved westward looking for gold or other means of economic survival, the opportunists tried to figure ways to sell the beauty of the area by offering places to stay for renewal and recreation away from the city. Some of those early settlers were able to stay year-round and leave their names and descendants to guide the town into new ventures and new centuries. Others moved on, leaving only whispers of memory. Estes Park has been discovered and rediscovered, touted as a tourist mecca and vilified as a tourist trap. Estes Park has seen boom and bust, the heartbreak of lives lost through floods and mountaineering accidents, the dreams of scores of entrepreneurs and retirees. Estes Park has been summer home or vacation retreat to millionaires, presidential candidates, company executives, school teachers, artists, rock stars,and hippies, as well as hundreds of thousands of “just plain folks.” Through it all, local residents have drawn solace from the beauty of the surrounding mountains and a pioneering spirit which recognizes that material goods are not the only reward for lives spent. History is a daily experience. And it is a reciprocal one. Your history becomes ours and ours becomes yours. August first is my 40th birthday. Moving into 2019, I made it my goal to hit 40 feeling awesome, at least physically. No diets, no scale, no strict workout routine. Instead, I promised myself that I would try to move my body every day. While I’ll admit that I’m kind of limping over the finish line with two toenails about to fall off, a skinned knee and a sore shoulder from my latest bicycle wreck, I am feeling healthy, fit and happy. I’m blessed to live in a place where there is no shortage of insanely fit people with whom to ski, trail run, mountain bike or rock climb. And even though I’m mainly there for the hot tub, you can even catch me doing bicep curls at the gym once in a while. I am filled with gratitude for my first 40 years on this precious planet. I am thankful for every single moment, good and bad, that have landed me in this spot. My Gosh, I am one lucky girl. I love these mountains. I can’t believe I get to live in this magical place with a wonderful man and amazing dogs. My body is healthy enough to allow me to go wherever my legs may take me. Summits, lakes, streams, trails, meadows, wildflowers and snowflakes are my religion. I didn’t need a lesson on appreciating each day and living in the moment, but the universe decided to give me one anyway on October 25, 2016 when my husband passed away in a climbing accident. After surviving the initial shock, anger, depression, anxiety and general hell that was my life for that first year, I can look back and honestly say that I am better for having gone through that, even grateful for it. What a strange thing, I know, to feel gratitude for a loss of this magnitude. I believe our highest highs are directly proportionate to our lowest lows. I know what it feels like to be in the fetal position, sobbing on the bathroom floor mid panic attack at 2 am. Those dark moments are a stark contrast to my current reality. These days Indian Paintbrush in that perfect shade of reddish-pink seem to jump out of the hillsides to greet me. The sweet vanilla-caramel smell of a Ponderosa Pine is richer now. I savor the sound of a quaking aspen grove or the cool spray of a waterfall like never before. I live and love differently now. I don’t get my panties in a bundle over the little things, but I also know how to stand up for myself and make my opinions heard. It has taken me these entire forty years to really come into my own. I feel strong, smart and beautiful. I feel confident enough to strip down to my skivvies and jump into an alpine lake without thinking twice about how my body might look. I love my scars, my freckled shoulders, my tanned legs and white belly. I’ve learned to love my body for what it can do instead of for the way that it looks. Rather than an extravagant trip or big celebration, I plan to spend my 40th birthday hiking with my girlfriends in Wild Basin. There’s nothing I’d rather do and no place I’d rather be! I’ve shed a lot of tears over the fact that my husband can’t be here for my special day, but in the same moments I am so grateful that I have such an amazing boyfriend who wants to share this chapter in my life. I have no idea how I got so lucky. There are not words to thank every single person with whom I’ve crossed paths in these last 40 years, especially my fellow mountain women!!! Here’s to the next 40 years of loving these mountains, loving myself and embracing the ups and downs, as I’m sure there will be many more! Rules of the Road By Sybil Barnes

I’ve had a Colorado driver’s license for more than fifty years. Not many things make me feel as old as that sentence does. Back in the day, one could get a learner’s permit at 15 and that meant driver’s ed was on the curriculum for sophomore or junior year in high school. One day a week we watched those gruesome state patrol videos with totally mangled cars and police officers giving us a serious look and a sonorous lecture about how dangerous it is to drink and drive. Or drive with a car full of teenagers trying to distract you by asking who your current crush was or whether you were going to the basketball game or the wrestling match. The other four days three of us at a time actually got to go out in a car with the teacher, who was also the football coach and the counsellor. The rest of us had study hall. Since there were more than twenty of us in the class, that meant we had a chance to be in the car every two weeks. And since it was a 90 minute period, that meant we each had about 20 minutes of time behind the wheel. Some days we drove around the downtown practicing how to parallel park and how to stop at red or yellow lights. Other days we went out in the country and learned about how to pass other cars or change a flat tire. The driver’s ed car had a “three on the tree” manual transmission, which was quite a challenge for some of us. Towards the end of the quarter when we all had mastered the basics, we each got a full period to be the driver on Skyline Drive, a one-way scenic loop along a hogback to the west of town. That was a challenge for those of us who felt the road was a little too narrow and winding on the way up. And we all had to learn to use a lower gear instead of riding the brake all the way down the steep east side, which we used as a sledding hill in the winter. I think about driver’s ed a lot when I go to Boulder or Loveland or over to Allenspark or Grand Lake. One of the first things we learned was “look at least three to five car lengths in front of you and scan both sides of the road as well as the traffic lanes.” This tip comes in handy when the elk or deer pop up from the ditch to cross the road and also when the car, two cars in front of you, decides to stop to turn into an unmarked driveway. Another tip was “try to keep a consistent speed.” My favored speed is 40-50 mph on dry pavement. There are only a few places where this means I am going under a posted speed limit of 55. Many times it means I am going over the posted speed limit of 35 for a curve. I have driven the four egress routes from Estes Park at least once a week and sometimes up to once or twice a day for many decades. I have some muscle memory about where those curves are. As long as the road is dry, the posted speed limit is conservative. When the roads are icy or snow-packed and/or when there’s fog, 35 mph is possibly too fast for any section of the road. My father used to say “Don’t take your half of the road out of the middle.” People who aren’t used to driving on curvy mountain roads tend to hug the center line and sometimes slide over it, so I usually tend toward the fog line on the outside of the road. It takes 30 minutes to get to Lyons. Plan for that. Once upon a time I had a low-slung muscle car which one of my friends described as moving like “a swift gray rain cloud.” In that car, late at night when there was no traffic, I’ve gotten to or from Lyons in 22 minutes. But I’ve also been in a line of traffic from Lyons to Estes for the Scottish Festival or some other event when it took 90 minutes to see Lake Estes. Now I have a Subaru. Even if you pass all the looky-loos going down/east on the straightaway at Meadowdale, you will probably end up behind somebody else before you get to the round house or Tedderville. And you will definitely end up just in front of the same car at the stoplight in Lyons. Or maybe you’ll be the lucky one who catches the attention of the Colorado State Patrol or the Larimer County Sheriff. The next place to pass legally is about nine miles out of town, near the house on the hill which used to have an entrance gate marked “Ensenada.” (There’s another way to identify yourself as “of a certain age.” You tend to make references to places and/or things that don’t exist anymore.) You can hope that the lollygagger in front of you in the rental car with fleet license plates will be intimidated by your aggressive tailgating and pull over before that at the Homestead Meadows trailhead parking lot, also known as Lion Gulch. But if you’re behind me and I’m already going 15 miles over the speed limit, I don’t think you need to pass. Cool your jets and enjoy the scenery. Just this past week there have been two crashes at the passing lanes just west of Lyons. Both resulted in fatalities. Considering the volume of traffic that uses this road, it surprises me that it doesn’t happen more often. As they used to say on some 1980s tv show (maybe Barney Miller or maybe Hill Street Blues) - Be safe out there by Rebecca Detterline Hiking to Ouzel Lake? I’m gonna need two jackets, rain pants, hat, gloves, first aid kit, water purification system, hand sanitizer, map, compass, sunscreen, headlamp, too many snacks and probably some wine. Running to Ouzel Lake? Well, I’ve got half a liter of water and five squares of toilet paper. No matter what size of pack I choose for a particular outing, I always seem to fill it. Outside of my very first solo backpacking trip to Lawn Lake (good thing I brought a four person tent), it’s hard for me to recall many times that I’ve truly overpacked for a backcountry outing. Underpacking, now that’s my real forte. There was the time I hiked Ouzel and Ogallala Peaks on a bluebird day without sunglasses or a cap. Once my friend Ben and I spent three days at the Hutcheson Lakes with plenty of Cup O’ Noodles and dehydrated ravioli, but no pot to cook them in. (He forgot shoes and hiked the whole time in Chaco sandals. He did bring a bottle of Sailor Jerry and a copy of Jimmy Buffet’s ‘A Salty Piece of Land,’ though.) And let’s not forget when I decided against bringing pants to Desolation Peaks on the windiest day I have ever experienced. (This tennis skirt should be fine!) No harness at the base of the Cables Route on Longs Peak in Winter conditions? Been there. While the underpacking situations are definitely more memorable, overpacking is much more common and something the majority of hikers could work on. While it’s important to have the essentials, hauling unnecessary gear up the trail just slows you down and frustrates your hiking partners. Do your friends a favor and check the weather forecast. If it’s a high of 75 degrees and 0% precipitation, do you really your down ski jacket and winter gloves? I try to consider the bare minimum and then throw in one extra layer just to be safe. Also, start off a little bit chilly. Don’t be that person that needs to stop five minutes from the trailhead to de-layer while everyone who dressed appropriately to start off with gets cold waiting for you. How much water do you really need to carry? Do you know how much three liters of water weighs? Me neither, but it’s way more than one liter and a SteriPen.(I love my SteriPen! Worth every penny!) Many trails offer lots of delicious rocky mountain snowmelt. A quick glance at your map will let you know where you can resupply. Get on the pre-hydration program and chug water the day before any big day in the backcountry. I have a strict ‘no booze’ rule the day before any big day in the mountains. As a bartender, I’ve seen so many people put down three pints of beer six hours before their first-ever Longs Peak attempt. Why? Start off hydrated and you won’t have lug a bunch of water uphill while fighting dehydration and a mild hangover. Only one person in the group needs to carry a first aid kit. If there is a situation that requires multiple triangle bandages and SAM splints, I’m probably going to send someone out for help. With these simple tips you can easily lighten your load or better yet, make more room in your pack for salami, cheese and red wine! Is this Brave New World of Blogging for me? by Sybil Barnes

I don’t remember when I learned to read. It seems like something I have always done and always enjoyed. I can be transported to Oz or Everest or the blue highways at the turn of any page. I find the list of ingredients on cereal boxes fascinating. In addition to being a reader, I always thought that I was a writer. I wrote letters to my friends and kept a diary until I began to call it a journal. I wrote little plays for the neighbor kids to perform in the backyard, created graphic novels from pictures cut out of the pages of catalogs and magazines, and thought up dialog to speak when we played cowboys and indians at school recess. In fifth grade, I wrote a haiku which was published in a national anthology. I can’t remember it now. Maybe it went something like: From the car, I see Ponies on the grass. Alas They do not see me. Were the judges impressed that a fifth grader would try to paraphrase or plagiarize Gertrude Stein? Am I kidding myself that I knew who Gertrude Stein was in 1960? Maybe she was an entry in the 1950 Book of Knowledge which was our home reference source. I just liked the way grass and alas sounded together. And I thought poetry, even Japanese poetry, had to rhyme. I realized much later that someone having their name in an anthology probably guaranteed another sale of the book. Maybe more than one if they had a large family. Skip ahead another decade. I graduated from college but I didn’t want to live in a city. So I came back to the mountains and got a job in food service. Then I bought a book store. After the 90-day economy of Estes Park and my own propensity to spend more than whatever profits I made in the remaining 275 days on entertainment of various forms convinced me that I wasn’t cut out to be a businesswoman, I was hired at the library. I still wasn’t writing anything. When anybody asked, I said I was working on a children’s book about my cat. So many years past that early success, I’m still not a writer. I get up before dawn to walk dogs or drive the mail to Allenspark and then I walk some more dogs or go to the library or a book group and then I walk some more dogs or scoop some litter boxes and go out to eat and maybe sit down with somebody else’s novel and fall asleep before the 10 o’clock news. Some afternoons or nights I go to movies and try to stay awake through them and the drive home from Boulder. Most evenings, I wake up on the couch to some 4 a.m. infomercial or a whining dog who needs to go out. After I pick up the book I have inevitably dropped on the floor, I start all over again. But maybe a deadline and a word limit will be the ticket to productivity. I’m only the length of this century late to the party. And I hope I won’t just add to the general detritus of your day. Or send you down a rabbit hole that will prevent you from realizing your own dreams or projects. Let’s just see how that goes.

We moved to Canon City, Colorado partly because my brother flunked first grade and my parents didn’t want him to have to repeat it here. I don’t think he ever learned to read very well. We came back every summer. That makes me eligible for the “almost local” group. And after college I moved here because my experiences in the real world qualified me as a country mouse and eligible for the “stay here” group. I’ve had jobs in every sector of the hospitality industry from scrubbing toilets to greeting customers at restaurants to owning a small business. My favorite career was as the local history librarian at the Estes Park Public Library and the reference librarian at Rocky Mountain National Park. I have a listing in the Library of Congress for a Story Corps interview with Enda Mills Kiley and also for my pictorial history of Estes Park, an Images of America book published by Arcadia in 2010. I’m interested in local history, current events, movies, plays and music, books, traveling, and random thoughts I hear or see on radio or tv or the street or even FaceBook. Maybe some of my posts will include those topics or others.

While I am always excited to see a place for the first time, attain a new summit or fish in a lake I’ve never visited, spring is the time of year to find comfort in the familiar; to return to the trails we’ve hiked dozens, if not hundreds of times. What a gift it is to revisit a favorite tree or boulder, to note the ever-melting snow drifts and enjoy the spring wildflowers as they begin to bloom seemingly one species at a time.

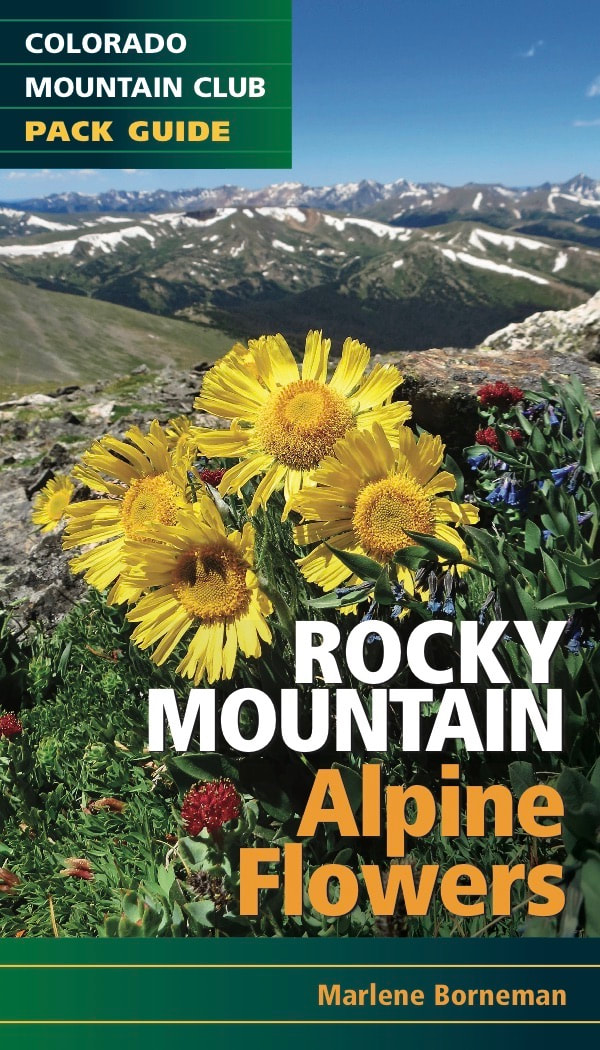

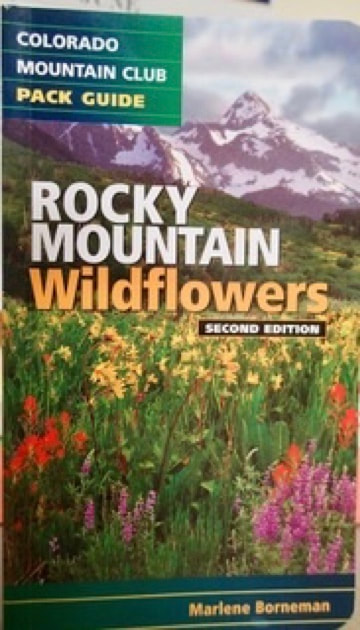

After the flood of 2013, the NPS put in a beautiful new bridge below the falls to replace the one that was washed away. I see a lot of folks admiring Ouzel Falls from this vantage point. It’s a lovely view, but an extra couple of minutes of rock-hopping and ducking under tree limbs will take you right up to the base of the falls. Regardless of what else may be going on in my life, any day I get to feel the spray of a waterfall is a pretty good day. Once the snow melts out, hikers can continue on an unmarked trail up to the big beautiful valley through which Ouzel Creek meanders before plummeting 40 feet and joining the North Saint Vrain Creek. This valley, which lies within the scar of the Ouzel Burn of 1978, is a lovely place to spend an afternoon fly fishing for small brook trout or simply enjoying the sounds of the gurgling creek while Ouzel Peak towers above you in the distance. Like me, the young aspens and fireweed in this area got their start on this beautiful planet during the summer of 1979. Nature presents us with many silent metaphors. The juxtaposition of charred trees and wildflowers reminds us that what appears completely void of life can be reborn. Calypso Orchids alongside a trail carpeted in last year’s dead aspen leaves give hope that that which appears to be completely void of life may be just moments from blooming. May we embrace this season of renewal and awakening with gratitude for the quiet lessons from Mother Earth. This is the season to return to return to the places that have greeted us year after year. Spring is a wonderful time to rediscover the lower elevation hikes in RMNP while reflecting on the past year and looking forward to the one that lies ahead. In addition to Ouzel Falls, my favorite spring hikes include Fern Falls, Bridal Veil Falls, West Creek Falls and MacGregor Falls. Mount Lady Washington is a lovely (although much more strenuous) springtime favorite at 13,281’. While the high peaks remain guarded by the lingering snow, I choose to embrace the springtime and its gifts, knowing that the season to stand atop summit after summit is just around the corner. “Hope is not born on mountain tops, but in valleys when you’re looking to the heights and peaks that you’ve yet to climb.” It's time for Ask Dr. Day Hikes: Dear RMDH, Hi! Do you know if flowers are starting to bloom along the Fern Lake Trail? ML KD Thanks for the question ML KD! The trail is definitely hike ready to The Pool and up to Fern Falls. Flowers are just starting to bloom along the lower section of the Fern Lake trail. I saw a few patches of Alpine Spring Beauties and the yellow Hollygrape mostly (and dandelions). And the aspens are starting to leaf out. As I drove into Moraine Park, I could see that the upper Big Thompson River had swelled to the top of the river banks from spring runoff, but has yet to flood the meadow. I also noticed that the parking at the Cub Lake trailhead was full at mid-day. mid-week in mid-May. The road to the Fern Lake trailhead was open and the parking lot there was full as well. As the photos below show, the trail to The Pool was snow free and dry, though not entirely runoff free. There were only a few snow patches of snow approaching Fern Falls and the Falls only had snow along the edges. I did not hike to Fern Lake but hikers coming sown said there was still a packed snow trail to the Lake and about knee deep snow if you stepped off the snow trail. Here is my introduction to Rocky Mountain National Park, Colorado’s Crown Jewel. Spending time in Rocky has brought to me not only the world of climbing but the world of wildflowers. I have immensely enjoyed learning and expanding my knowledge of Rocky Mountain Wildflowers and had the honor of the Colorado Mountain Club to publish three pack guides I authored. The Alpine Flowers pack guide will be available in March, 2019. You never know how spending time in Rocky Mountain National Park will change your life forever! MY BEGINNING OF THE FINAL THREE It began innocently enough in 1974. That is when I came to Colorado for a summer job at the YMCA of The Rockies in Estes Park. I arrived from New Orleans, yes below sea level, in mid-May that year. Being a proper southern young lady I wanted to make a good impression on my new employer. I had worn a sleeveless silk dress, rather short as I recall, stockings and the cutest little heeled sandals you ever laid eyes on. It was approximately 30 degrees and spitting snow. I must tell you, my arrival ended up to be one of the scariest days of my young life. I recall saying to myself, “I have made a terrible mistake!”

From a short silk dress to summits, my progression came fast. By the end of that summer I had climbed most of the major peaks in Rocky Mountain National Park. Having graduated from college, I decided to stay in Colorado. You might say the rest is history, but it was not that simple. I lived in Estes Park for twelve years and climbed in Rocky year-round. I found myself focused on the major peaks, different routes with a few new peaks thrown in once in awhile. Then came a career move away from Colorado and my beloved mountains. To say I began grieving would be an understatement. I made the effort to spend a lot of my summers back in Rocky with “my” familiar peaks. In 2001, I returned to live full time again in Estes Park. Dorothy may have been on to something, “There is no place like home.” After completing the 54 Fouteeners in 2005, I was hit with a pain of guilt. I imagine you all know what it’s like to ignore a friendship. This was worse; it was like neglecting your own husband. After all, Rocky Mountain National Park was now my backyard! I began to rekindle my relationship with Rocky, started studying the map with new interest and curiosity.

Then, reality struck me hard. THE FINAL THREE were The Sharkstooth, Hayden Spire (both Class 5 technical climbs) and Pilot Mountain a difficult Class 4 climb. Had I set myself up for this? Shouldn’t the last peak be easy, like Estes Cone or Twin Sisters? I hadn’t climbed anything beyond Class 4 in years. I came to the realization that THE FINAL THREE were meant to be my grand finale. I needed a challenge; I wanted a challenge! I needed to gain my confidence back on the rope; I needed a plan. It sounds like I needed a lot! The Sharkstooth was the first of my FINAL THREE. My climbing partner and I left the parking lot at 3:45a.m. I once read that eighty percent of success is just showing up, I liked my chances.

As I climbed toward the summit tears were in my eyes. This was what it was about: I hadn’t gotten here because of a list, but because I had taken on the challenge of exploring the new. For me this comes with great joy, satisfaction and fulfillment. Next was Pilot Mountain, which thinking back, I over rated the difficulty. It was a fun Class 4 climb in Wild Basin. The ridge out to the summit is awesome and the view of Falcon Lake from the summit breath-taking! The last of the FINAL THREE was Hayden Spire. I had admired this peak from afar for decades, now I was coming close to standing on the summit.

Reflecting on THE FINAL THREE, I will forever remember the air beneath my feet, the sudden flight and song of finches above my head, the sense of inner relaxation and burst of excitement at the same moment and the incredible sound of the silence around me. THE FINAL THREE was my way of remembering Dick’s 20+ year companionship on these peaks. In the mountaineering world this is a speck. But it is my speck in my world and I am grateful for the opportunity to hold it in my heart. You may ask, is there anything left of that southern girl from 1974? I like to think so. My father was a riverboat captain; he lived with patience, endurance and perseverance. I like to think I gained these traits from him. And, oh yes, I still love wearing silk dresses (a little longer now) and cute heeled sandals.

Marlene has climbed Colorado’s 54 14ers, the 126 USGS named peaks in Rocky Mountain National Park and 44 State High Points. She has been a member of the Colorado Mountain Club since 1979 and is a member of the Colorado Native Plant Society. She teaches wildflower classes for the Rocky Mountain Conservancy and provides community programs to educate and promote stewardship for Colorado’s wildflowers. Marlene holds a Masters Degree in Social Work and a Certification in Addiction Counseling. She guides in Rocky Mountain National Park and enjoys sharing the scenery as well as her knowledge of the plant life and habitats the park has to offer. She is the author of Rocky Mountain Wildflowers 2Ed. and The Best Front Range Wildflower Hikes, and Rocky Mountain Alpine Flowers, published by CMC Press.

There's good hiking snow free at Wild Basin for a few miles, but only because the road to the Wild Basin trailhead is closed a mile before. That didn't stop an overflow parking lot of people from getting out on Sunday, people are anxious to get hiking. And the trail is mostly snow free and not terribly muddy up to Lower Copeland Falls. After that, it's a mix but drying out, up to the bridge over the North St. Vrain River. The river if also snow free up to that point, but only starting to swell with spring runoff. However, the final uphill stretch after the bridge quickly becomes snow covered, and it's slick going from there on. The lower portion of the Deer Mtn trail is in great shape. But once in the trees, there was plenty of snow coverage, and it was slick. The legs are tense all the way up and down trying to stay upright. Once on the flat top portion, before the final summit push, the snowshoer from the last snow couldn't find the trail. So there are all kinds of people following the wanderings of this semi lost snowshoer, and as the the snow melts, people are walking over vegetation and postholing at fallen logs. But the wayward snow trail does eventually make it's way to the summit. Subscribe to Note from the Trail rockymountaindayhikes.com/deer-mountain-31.html

The Cub Lake trail starts as one of the lower elevation trails and a good one to hike early in the season. The trail yesterday was not really ready for hiking just yet. There were a few hike ready dry spots, but most of the trail was filled with spring run off and it was a trick navigating and rock hopping to stay out of the wet spots. Please be sure to click on an image to see it larger. Two days after the Spring Equinox, Mother Nature announced spring had arrived in the mountains of Rocky Mountain National Park and the Estes Valley with a booming afternoon thunderstorm that resulted in a small amount of spring snow. There were already signs of spring around though. RMNP Trails was reporting the Hooker’s Townsend Daisy (Easter Daisy) already in full bloom along the sunny and low elevation Lumpy Ridge, there were reports of a bear in a tree in the Riverside Dr area, an aspen patch not far from the Beaver’s Meadow Visitor Center had started to bloom catkins, and chipmunks appeared around my bird feeder. The weather report is calling for more snow on Friday. It must be spring time in the Rockies. The trails in the lower montane regions of the Park are treacherous right now. The packed snow on the trails melt into a slush during the day but freeze into a glaze overnight. Either micro spikes or ice skates are needed. And if the ice does melt off, it often leaves a slimy muddy patch to slip and slide on, challenging ones aerobic agilities. If you really want a taste of spring now, it might be best to head for a trail down around Lyons. Otherwise, just head back up into winter in the subalpine Bear Lake area. That’s where I went. I wanted to make another try at Timberline Falls. On the morning I had planned to journey up, the skies were overcast and not looking good. So I thought I would wait a day for improved conditions. But, of course, by afternoon the

Even though it looked like winter, the day was warm and the conditions were starting to change. A squirrel scurried in front of me across the snow. It stopped briefly to consider me, but it seemed to be on a tight schedule and quickly disappeared. I trekked along in this first portion of the hike lost in thought about the different ways people connect with nature. For some, a journey into the high mountains is held with a quiet reverence. But children like to play in nature and seldom show such reverence. I thought about how reverence for nature seems to develop for them through their playfulness.

I resumed my hike up the snow filled drainage when a couple of skiers swooshed down, working to maintain control. They stopped briefly uphill from me and I asked them where they had skied from. They had gone up to Andrews Glacier but decided the conditions were not favorable, so they turned back. They had had a good day

led to the base of the drift where someone with snow shovels had mined out snow caves. The opening of one I checked out was small and I peaked in to see a small room that might cozily fit three or four people. Turning back to the main snow trail, another skier slid to a stop and asked how big the snow caves were. He was carrying an overnight pack and had spent the night out somewhere on the far end of The Loch. It had been a good night with out much wind. I It was practically a windless day at The Loch and I found a seat beneath one of the wind twisted Bristle Pines and watched the clouds shift around. What ever blue sky there might have been over the peaks earlier was quickly disappearing. I pulled some I packed up my pack and finished my trek to the snow covered Timberline Falls. The clouds were moving down on the peaks now so I turned to head back.

Why is the return always longer when it’s not? This last week, after the snowbomb cyclone that hit the high plains with a vengeance, I tried out Wild Basin. I had not been there yet this winter and I found the road closed at the entrance gate; that would add some distance to the destination. The road was well covered with snow though, and the trail had not been packed down too much yet. I shoed around Copeland Lake and along the lower section of the road, going past the mid way gate that is the usual winter parking area. The walk to the Thunder Lake trailhead was an enjoyable travel, with a stop along the river in one of the few places that had open water. There were fluffy piles of snow perched on top of boulders and thin slices of ice where the boulders met the surface water. The open water maneuvered around the boulders and sounded a little like a summer mountain stream, pleasant. It was quite amazing to look around and see all the water that was about to melt and run down toward the Mississippi Delta and think of all of the flooding that it will do along the way over the next couple of months (there’s a report coming out of Chatham in the UP of Michigan of snow depths over 200 inches, yes, over 16 ft of snow, holy wuh!!!).  I past by the Finch Lk trailhead quickly and then rounded the corner to the Thunder Lk trailhead. I had a good pace going and it didn’t seem to take too long to get there. I walked onto the little foot bridge that crossed the small creek at the trailhead and stopped to see if there was any open water, but there was not, it was all snow. I continued into the trees. A skier somewhere up ahead was breaking trail. He had passed me back on the road and when he passed, I notice he was not carrying a day pack. But peeking out of his back pocket, I could see the top of a soda can and by the color of it, it looked to be Dr Pepper. At least he was packing some energy. I tried to stay out of his tracks because I have heard somewhere that snowshoes can wreck a good ski track.  My friend, the aspen My friend, the aspen I noticed all of the familiar spots along that lower section of the trail and that some of the understory trees were still holding snow on their branches, while all the tall skinny trees that were being swayed by a warmish wind higher up had already lost their snow. I branched off to the Lower Copeland Falls but found it covered with bunches of snow all over. On the way up to the upper falls, I stopped and looked at some aspens. Most of them were showing red tips that had emerged on the end of the branches. They were thinking about summer also.  I arrived at the upper falls and found more open water from the little bit of turbulence coming off falls, covered over with deep snow. I remembered being here during the summer and watching a pair of Ouzel birds that habitated here. At that time, the falls were roaring with summer runoff and the Ouzels kept flying to a spot on the small cliff that embraces the falls. I assumed they had a nest there. While I sat there watching them busily catching food in the water below the loud falls, often diving under the water, I thought about how the only sound the young would ever hear until they flew from the nest would be the roar of the fall, which I thought was loader than city traffic. It’s a very sustained loud sound next to the falls.  Upper Copeland Falls Upper Copeland Falls I imagine they would know that river sound so well that they could heard different sounds coming from the river that I would never notice. Although John Muir heard those sounds when he was writing about the Sierra Ouzels: “[H]is music is that of the streams refined and spiritualized. The deep booming notes of the falls are in it, the trills of the rapids, the gurgling of margin eddies, the low whispering of level reaches, and the sweet tinkle of separate drops oozing from the ends of mosses and falling into tranquil ponds.” ~ Muir 1894 (I really need to listen to the sounds of water falls better!!) But I didn’t see any Ouzels flying around today and I wondered what they did during the winter (John Muir’s Ouzel, now officially known as the American Dipper, migrate altitudinally, that is moving to lower elevation during the winter, so says audubon.org). While I was at the falls, I had a drink of water and a bite to eat and I wondered how much farther I should go. I traveled up the trail a little further, but not as far the Calypso Cascades. By the way the snow was covering over the river down lower, I figured they were likely covered with snow also and hardly recognizable.  I was stooped down in the snow photographing a small patch of open water when the skier that had been breaking trail skied past on his return. I asked him if had made to the falls. He had, but was gone before I could ask how they were. I decided it was time to turn back also. Retracing the tracks the skier and I had made, we ran into another set of tracks that only went as far as the lower falls. Having already pass through all of this, I didn’t feel a reason to stop, I was more focused on the return. I traveled as if I were in a hurry to get somewhere. And this is where the going seemed to get longer. Even though I’m sure I was not taking as much time, all of a sudden, the road seemed to be twice as long as before and I wondered in the moment, numerous times, why this was. The day had grown warm and the snow had become soft. I traveled with my coat unzipped and my hat in my hand. As I past people who were just heading out, so late in the day it seemed, they all gave me a smile. I gave them a friendly hello back, but kept up my pace. It seemed to be taking forever to get to Copeland Lake. But then, there it was and though I hustled around, I felt like I was dragging. Finally, the parking area and then the car. After taking the snowshoes off, I hopped into the front seat and happened to catch a glimpse in the rearview mirror, and then took a closer look. My strands of hair looked as if they had just gone limp from a jolt of electric shock, they were sticking out every which way. And just like the people that had passed me, I smiled. “I swear I begin to see little or nothing in audible words, All merges toward the presentation of the unspoken meanings of the earth, Toward him who sings the songs of the body and of the truths of the earth, Toward him who makes dictionaries of words that print cannot touch. “I swear I see what is better than to tell the best, It is always to leave the best untold. When I undertake to tell the best I find I cannot, My tongue is ineffectual on its pivots, My breath will not be obedient to its organs, I become a dumb man.” Walt Whitman, from A Song of the Rolling Earth, Leaves of Grass “Moreover, I find that though I have a few thoughts entangled in the fibers of my mind, I possess no words into which I can shape them. You tell me that I must be patient and reach out and grope in lexicon granaries for the words I want. But if some loquacious angel were to touch my lips with literary fire, bestowing every word of Webster, I would scarce thank him for the gift, because most of the words of the English language are made of mud, for muddy purposes, while those invented to contain spiritual matter are doubtful and unfixed in capacity and form, as wind-ridden mist-rags.” John Muir in a letter to Jeanne C. Carr, a former professor  These are the struggles that two great nature writers, a generation and a continent apart, find themselves in; words that are not adequate to express what they experience in nature. And yet Whitman and Muir do write, splendidly, exquisitely. How can I possibly think that I will find the words in these notes that I jot down about my experience in nature? I do not. And while I’m under no allusion that my words will do anything but possibly get across some notion of what my experience in nature is, I will also write because, what the heck, what I experience in nature is worth the try. I cross over the hump of piled snow left by the snowplow in front of the gate that closes Trail Ridge Road at Many Parks Curve. I clip into my skis and follow the snow path made by a couple of snowshoers. Fresh snow has fallen and avalanches are crashing down all over the state, closing roads that haven’t been shut down from the overpowering snow slides in over a half a century. But here, it’s quiet, not even wind music, and I’m caught up with making my skis function. Because I still ski on skis that need wax for propulsion, and because I forgot to tend to my skis by putting on new wax before I left and so I am going with whatever wax was left on the skis from my last outing, and because this snow can be so difficult to wax for which can cause the skis to either not grip and slip too much or form large clods of snow that hang off the bottom of the skis making them impossible to move, I wonder about how well things will go. But so far, everything seems fine. So I keep moving forward. The new snow is warm snow; good snow for building snow forts and stockpiling a collection of snowballs to be lobed at others. But I am an army of one fighting against an army of none, so the effort is left behind. There are views down into Horseshoe Park, but the encompassing peaks are hidden by low clouds. The somewhat wetter snow clings easily to the trees, and though it is fresh, it seems to hang on the branches like damp laundry.  Of course, the very thing that Whitman and Muir find so impossible to write about is not simply describing the beauty they see in nature, but the spirit or essence of nature, the internal eternal that one experiences in nature. Nature is more than beauty, it is a life unto its own and when we walk into nature, we are entering a world that already exists, we are walking into a life that knows how to take care of itself, and does so with such exquisite beauty and grace that it feels magical. We are left in wonder. There’s an outward bending curve in the road as it follows the contour of the hillside and it would seem the wind must always blow around this bend because, despite the many feet of snowfall that has accumulated all around, there is pavement showing here. And indeed, the wind is now gusting snow into my face and I lower my head letting the top of my hat take the pelting. But not long after, back in the trees and no longer in wind, the snowshoe tracks lead off to the outter edge of the road where they sit and rest on a rock wall. But the snowshoers have had enough and their tracks head back, leaving me to break a new track. Without even the snowshoe tracks to keep me company, the surroundings now seem quieter and I begin to trace a skinny trail as I head farther up the road.  “I swear the earth shall surely be complete to him or her who shall be complete, The earth remains jagged and broken to him or her who remains jagged and broken.” ~ Whitman I fall into a steady rhythm and my eyes focus primarily on the forward placement of the skis, occasionally looking up to track my progress. But my mind wonders into all sorts of everyday thoughts. Fortunately, the extra work of making a new track forces me to take a few more breaks and I am given an opportunity to gander about while catching my breath. My mind also takes an opportunity to rest and soak in the silence and calm. This is what I came to find. The clouds dissipate some and the sunlight falls between the trees and lands gently onto the snow. Rocky Mountain National Park is remarkable, in part, because of the rapid rise in elevation. If a raven were to lift off from the top branch of a ponderosa pine at the Beaver Meadows Visitor Center and fly a straight line to the top of Flattop Mtn, that raven would have flown 8 miles and gained 4,524ft (if another raven also took flight from a nearby ponderosa and headed south for 8 miles, that raven would have to gain 6,459ft in order to land on top of Longs Peak). Over that short 8 miles, these two ravens would have flown over extremely varied terrain and vegetation, classified as the montane, the subalpine, and the alpine life zones. It is a quick lesson on the significance that elevation plays for life on this planet. During the winter, that elevation change plays out in snowfall amounts. On any given winter day, it would be possible to leave the beaver meadows area on a somewhat mild day with patches of snow caught in bushes and hiding in the shadows, and drive up the Bear Lake corridor into full on winter with many feet of snow. Thus becomes the dilemma for the traveler on foot. What foot gear do you use, because many trails can begin with not much snow, where micro spikes are good for ice patches on the frozen dirt trail, but farther up the trail there’s deep snow where skis or snowshoes are the thing to have on your feet. If you want to start on snow, there are basically three main ski corridors in the Bear Lake area. There’s the trial that goes up the Glacier Gorge and leads to MIlls Lake and the Loch, the short trail to Dream and Emerald Lakes that the photographers like to run up in the early morning hours to catch the gorgeous sunrises off of Hallet Pk, and the longer trail toward Flattop Mtn, Bierstadt Lake, and Lake Helene located below Notchtop Mtn. Generally speaking, if you are breaking trail after a fresh snow it can be pretty easy to know where the trail goes through the trees. However, there is one spot on the way to Lake Helene where trail location can be difficult. I followed some tracks that had lost the trail on my way over to Lake Helene. Quite a meander. I finally gave up and navigated my own way.  Looking into the upper Glacier Gorge from the Flattop Mtn trail Looking into the upper Glacier Gorge from the Flattop Mtn trail I began at the at Bear Lake parking lot at a lazy 10:00. The day was clear, warmish, and mostly calm with some breeze, and for most of the day I traveled without my hat and gloves on and my coat unzipped. Taking the Flattop Mtn trail from Bear Lake, I snowshoed on packed snow past the first cutoff for Bierstadt Lake at 10:20 and the next cutoff for Flattop Mtn at 10:40. At 10:50, heading toward Lake Helene now, I passed under ski tracks that were making turns coming down through the trees on my left, while the trees on my right opened up to views looking east all the way down to the meadows around Lake Estes. Longs Peak peaked through trees behind me from the south. Looking down over the view of the surrounding forest on this day, it looked almost like summer because all of the snow had fallen off the trees and was hiding below them. The only real sign of winter was a white dot surrounded by green pines. That dot was the ice and snow that covered over Bierstadt Lake.

windswept snow. Some call this the Flattop Drift and like skiing this hard pack snow. From this point, the traveler makes a bee line across this open section just above the tree line. The trail on the other side dips back into the protected trees. Finding that spot where the trail enters the trees can sometimes be difficult. If you are the first one out after a fresh snow, there will likely be others that will follow in your tracks. I guess it could be fun to take everyone on a wild goose chase in search of the trail. Or, you could just head off in the right direction. Notchtop Mtn comes into view. In the summer, the trail goes around Two Rivers Lake and you hardly notice the pond is there. But in the winter, that’s where you want to go. In fact, the photography is better from Two Rivers Lake than Lake Helene. Two Rivers is a bigger pond and sits back from Notchtop for a better photographic composition, whereas Notchtop soars over Lake Helene so much it’s hard to effectively get a good photograph of it all. Also the ice is better at Two Rivers Lake, maybe because it’s a deeper pond.

From Lake Helene, one does get a good view into the Ptarmigan Glacier basin, which Notchtop overlooks to the south. It’s a collection basin for snow and it looks like it’s going to be winter up there for a while. The wind plays with some snow dust on the Thin clouds had materialized overhead, but the midday sun was still doing its best to start the melting process. That seemed like an unlikely process for a while with more spring snows still to collect. But everyday, the sun gets its licks in and sends rivulets of water down slope and into the Big Thompson River. I walk over to the edge and look down on Odessa Lake where the rivulets of water flow into and out of.

behind the ridge. 3 days later, the deck is covered with a foot of snow. More winter ventures yet to come.

I came to a spot where I wasn’t quite sure which way the trail went. Up to this point the trail had been easy to follow, despite the deep snow. But here, the trail could go either way. With my snowshoes, I paddled off to the left of the big snow covered fir tree and began navigating, keeping the creek on my right. The way I chose was not the trail way, but that was ok because I knew how to get to where I wanted to go. I saw hoof prints in the snow, but they had a layer of snow on top of them, so I knew they were not fresh. And were those elk turds or moose? Also not fresh. Navigating through some trees, I came upon a spot where a large animal had been laying. This did seem fairly fresh and I stepped just outside of the bedding spot. I continued through some more trees, keeping the snow covered stream on my right. I could see the stream was heading toward a small canyon wall on the left, with dashes of snow on narrow ledges dotting the cliff. And then there it was! Off to the right standing by the creek and looking at me through some short aspens, a moose! I stopped in my tracks and looked at it. It was not a big moose and she stood there looking at me. As I glanced around for others,

With the stream cutting toward the canyon wall, I had to find a narrow spot to cross. There was a spot where a patch of snow formed a bridge across the ice. With the moose watching, and probably hoping I would break through the ice and fall in, I placed my left snowshoe down along the edge of the bridge and stretched my right snowshoe as far over to the other side of the snow bridge as I could. When I began to push off with my left foot, I heard the thin ice underneath the snow start to give way, but it did not. I sidestepped over and there I was with the wooded forest stretching upslope ahead of me and away from the moose. I glanced back, wished the moose a good day and again apologized for disturbing her. I started to make my way up through the trees, scanning the surroundings for the best route to take. In mostly aspens, it was fairly open traveling with about a foot or more of snow. This was the first time I had used the snowshoes off trail and I found the navigation around the trees much less complex than when I used to do this kind of thing with my 190mm cross country skis with 3 pin bindings. It had been a long time, but I remembered how fun it was to wander about the woods like this. Suddenly this feeling of joy welled up from within. I was wandering in the woods! I felt free! I loved making my way through the woods in the winter, and the snowshoes were making it really easy to do (I had resisted for so long). That feeling, that delight temperature a little cool, but my feet were warm, and I was warm and myself, finally. I had found myself, here in this moment of pure joy. It felt so good to feel that again. It was a moment I was ready for and I felt a little bit of healing occur from within.

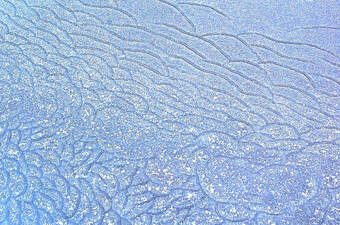

The reddish orange canyon walls rose up across the stream and contrasted with the white snow. There were thick icicles hanging off an overhang. I navigated away uphill, and then suddenly, there was the trail! I looked back from where I had come and smiled. Nothing. I turned the key in the ignition again, and again, nothing. This trip to Timberline Falls in the Loch Vale was not off to a good start and I thought about bailing right then and there. But, after finally getting a jump from a friend, I was at the Glacier Gorge parking lot by noon. Just a little late. I started gathering my gear, pack, camera bag, poles, snowshoes. Huh? Where are the snowshoes? Huh! Did I really forget to load the snowshoes? Wow! I guess if I was looking for reason to bail, this would do it.  Well, I thought to myself sitting in the parking lot, the trail to Alberta Falls should be well packed from snowshoers. In fact, I would guess that most of the people on the trail at this time of year would be going well beyond the one mile to Alberta Falls and are snowshoeing to either Mills Lake or The Loch. And since we had not had any fresh snow in a while, there was a good chance I could get to one of the two lakes just hiking in my boots on packed snow. As late as the day was though, and without the snowshoes, Timberline Falls was not going to be in the cards today. Alright, I told myself, I’ll get on the trail and just see how things go. About an hour latter, I was at the trail junction for Mills Lake and The Loch. The day was warm and there wasn’t any fresh snow on the trees, and Alberta Falls was so filled in with snow it wasn’t even recognizable as a waterfall. As I walked along, I watched for interesting shadow patterns in the trees to photograph, but nothing had caught my attention. Standing at the junction, I debated which lake I should go to. I looked at the sun, low on the horizon, it would be setting behind the mountain ridges soon.  According to the trail sign, The Loch was 0.8 miles away, only 0.2 miles more than Mills Lake (though getting to the Loch always seemed to take much longer to me). But I decided to hike up to The Loch anyways, since that was on the way to my original destination. Not too far up the trail, I stop to quiz Steve and Walt who were coming down from The Loch. They also did not have snowshoes on. I asked how things went. Steve said they would have faired better with snowshoes. Walt said there was a spot where the trail just disappeared under the snow. I knew where that spot was, I had encountered that spot before when winter trekking to The Loch. In fact, this is one of the last places for the snow to melt off this trail in early summer. It’s a spot where the terrain begins to descend below the lake. The winter winds drop off the high peaks that surround The Loch, gathering considerable speed and snow, before shooting across the lake, sandpapering the ice and blasting any trees and persons in its path. The wind then launches straight out over the tops of the trees from the lake. But at this particular  spot about 30-40 yards below the lake, some of the snow carried by the wind drops out and creates a sizable drift over the trail. It usually means losing all traces of the trail and knee deep wading for a little bit if you didn’t have snowshoes. I felt I could manage that. They also commented on how strong the wind gusts were while they sat for lunch at the lake. But Steve said it was absolutely gorgeous there. I knew that was true. I thanked them for the info and continued on, but only for a few moments. I decided it was not too late to change my mind and head for Mills Lake instead. At this point in the day, Mills Lake just seemed like a better destination. I don’t know if it’s true or not, but it always seems like the wind is stronger at The Loch. I speculated that it had something to do with The Loch’s east-west orientation whereas the ridges on either side of Mills Lake were oriented more north-south. A fine bit of pure speculation, I thought to myself, and soon I was crossing over the open rock slabs that lead to Mills Lake at just past 1:30.  It was windy at the lake, but not horrendous. The wind had done a terrific job of clearing the snow off the entire ice covered lake and the ice was thick and polished smooth. I dropped my pack, pulled my camera out of the bag and started taking pictures. Though the sun was casting shadows off The Spearhead farther up, there was still sun on the icy lake. Snow filled the cracks in the ice, creating interesting patterns, and I ventured out onto the slick ice a little ways and dropped down to photograph the patterns. The wind caught me camera bag and scooted it back across the ice toward the shoreline. I moved around to different parts of the lake trying to bring the large boulders protruding from the ice into the foreground. At one point a jet raced through my photo, leaving a contrail stretching behind it like a taut piece of white yarn. Wrecking the photo I had just set up, I rolled over on the ice and groaned. The shadow from the west ridge was beginning to move across the lake now and I moved up the shoreline trying to stay in the sunlight. But once the shadow had drifted across the lake, I packed up and started to head back, happy I had made it before losing the sun at 2 o’clock. There were a couple of other people taking pictures and one commented to me that they liked the light with the shadow on the lake. I looked back and saw interesting light patterns.  The surrounding peaks were still basking in the late day sun and they cast a reflection on the ice that was not seen until west ridge blocked the sun. The reflected lighting created little shadows on the dimples in the surface of the ice as if frozen lake ripples. To the right, the southern ridge line blocked the reflection leaving subtle shades of rippled blue. A very different and beautiful kind of image emerged with the shadow. Though the sun on the distant peaks drew the immediate attention of the eye, the real beauty was found in the shadow with its varied color and texture. Once again, as with much of this day, I reconsidered things, reached for my camera and tripod, and stayed a little longer at the lake. There were many opportunities to walk away today, and sometimes the situation is such that turning back makes the most sense. But often if we stay open, we can find a way forward, even if the outcome might be different than what we had originally envisioned.

I swung my car onto the Moraine Park Campground road and looked beyond the vast Moraine Park up into the mountain valleys where my destination lie and I knew at that point I wasn’t going to be having any lunch at my destination. My destination was Fern Lake and from the looks of things, there were ferocious winds and snow channeling its I parked in an empty parking lot at 8:50 am. This was going to be one of those rare days in the Park when no one was going to be on the trail. I was on my own on this day. From the trailhead, the Lake is listed as 3.8 miles, but nobody gets a parking spot at the trailhead anymore. Either the small lot is full in the summer, or the road going to it is closed for the winter, like today. The walk from the extended parking lot, where the shuttle bus will drop you off, is an additional .7 miles. So, the real distance to Fern Lake is four and a half miles, or 9 miles round trip. I grabbed my snowshoes out of the car and hoisted them under my left arm. There was only a thin layer of packed snow on the road from the parking lot, and there wasn’t likely going to be any significant snow all the way to the Pool, 2.4 miles away. I wasn’t sure just how much snow I would encounter after the Pool, but I was very sure I would need the snowshoes somewhere after that. So carrying them seemed the best option to me, better than wearing them over rock and frozen dirt. I was curious about the conditions up higher because we hadn’t gotten very much snow in Estes for quite a while. And, I guess, I wondered just how adverse and horrendous I would find the conditions at the lake. I also wondered how I would do getting up there, I had not done a winter outing like this in a while. I felt like I was dressed for winter travel, and I didn’t really question my ability to get up there, though I wondered how worn I would feel by the end. But I think I wanted to see what it would but here in the trees, the wind was mostly overhead, and travel on the trail along the Big Thompson River was familiar and easy going. I stopped several times, putting down the snowshoes, to photograph the frozen river ripples on the river and consider the undulating and sensuous form and beauty of the ice. Even in its frozen state, the river was to be admired. Though water still flowed below the ice, the river was silent. But the noise from the constant raging wind overhead filled the void left by the river and made me want to keep moving. Soon I was at the Pool. I thought this might be a good time to put the snowshoes on, but then thought the trail for the next half mile might still be mostly cleared, so I carried my snowshoes about another 30 yards and then encountered a sizable drift over the trail. I went ahead and put them on and I didn’t regret having done that, I found there would be plenty of snow from here on. This next brief section of trail above the Pool stills travels along the valley floor and three streams converge along this stretch. After I carefully negotiated a narrow footbridge with my snowshoes, the trail begins to rise up toward the glaciated hanging valleys of the Odessa Gorge by crossing the south hillside of Spruce Canyon. From the trail in the trees I could hear the constant wind tearing out of Spruce Canyon like a high pitched freight train. The trail switchbacks through tall spruce trees to Fern Falls, then cuts west and switchbacks again before finally turning towards Fern Lake. By now, most of the elevation to Fern Lake has been gained and there’s considerably deeper snow. Even though there are no new tracks and the wind has covered over most of the old tracks at this point, the snow path is easy to follow as it holds a steady course through the spruce trees. Some trees are holding up other trees that have died and fallen into their arms and all along the trail you can hear these trees that are holding the dead moan and squeak and sing, caused by the friction between the two trees as they sway in the wind. I knew if I approached the lake in the normal way over that rise, I would likely get blasted with a face full of freezing wind gusts, which didn’t appeal to me. I opted to work around the back side of the patrol cabin through the trees. The snow was piled up super deep here and my snowshoes were having trouble keeping me afloat. But I paddled my way through the snow and down to the lake’s edge. There were patches of exposed ice out on the lake where the main wind channel flowed. In order to get the obligatory lake photo, I kept the wind to my back and skirted the edge of the lake, finally wading across that wind channel to the lakes outlet. Along the lakes edge, the wind sculptures interesting patterns and I would have loved to spend some time photographing these pieces of nature art . But the lighting was camera bag for very long. So I huddled behind some small pines and peaked around them across the lake and up the Gorge. On a clear day, Notchtop, the Little Matterhorn and Gabletop provide supreme backdrops to the lake. But on this day, the other side of the lake was hardly visible and only Galbetop struggle to barely appear from the low, snow filled clouds, and my camera’s exposure didn’t even acknowledge its effort. Not finding much reason to dilly dally any longer, I left the lake to be more thoroughly enjoyed on another day. My destination was reached, and it was lunch time. I retraced my steps back and quickly descended to Fern Falls before dropping my day pack for a bite. Then I moved back down the trail at a good pace. I was surprised that at certain sections of the trail, the wind had already blown over my own tracks from just less than two hours ago and at one point, back down on the valley floor before the foot bridge, I briefly lost the trail. But then I was back at the Pool removing the snowshoes and continued without stopping until I reached the trailhead. By 2:50, I was back at the car, a 6 hour day. My pace averaged 1.5 miles an hour, including stops.

of an effort. Winter though has it’s own beauty, of course. And if you accept it for what it is, a part of a larger seasonal picture, it is possible to find the connection. But just to be sure, I think I’ll take a few trips.

We are not built to survive in these conditions for very long, but we are at times built, for briefs moments, to laugh at them and smile at them, or be humbled by winter’s ferociousness. And there are those rare souls that find winter their greatest joy, live for the defiance, find love and happiness even in all the desolation of winter.

Some call this sort of nature pondering mindfulness, a wakeful presence, a form of spiritual practice. Laura Sewell observes that “perception, consciousness, and behavior are interdependent. Skillful perception is the practice of intentionally sensing with our eyes, pores, and hearts wide open.” Being in nature can slow time, provide solitude for contemplation and reflection. And through this process, there can be growth, even as one is grieving.

|

"The wild requires that we learn the terrain, nod to all the plants and animals and birds, ford the streams and cross the ridges, and tell a good story when we get back home." ~ Gary Snyder

Categories

All

“Hiking -I don’t like either the word or the thing. People ought to saunter in the mountains - not hike! Do you know the origin of the word ‘saunter?’ It’s a beautiful word. Away back in the Middle Ages people used to go on pilgrimages to the Holy Land, and when people in the villages through which they passed asked where they were going, they would reply, A la sainte terre,’ ‘To the Holy Land.’ And so they became known as sainte-terre-ers or saunterers. Now these mountains are our Holy Land, and we ought to saunter through them reverently, not ‘hike’ through them.” ~ John Muir |

© Copyright 2025 Barefoot Publications, All Rights Reserved