|

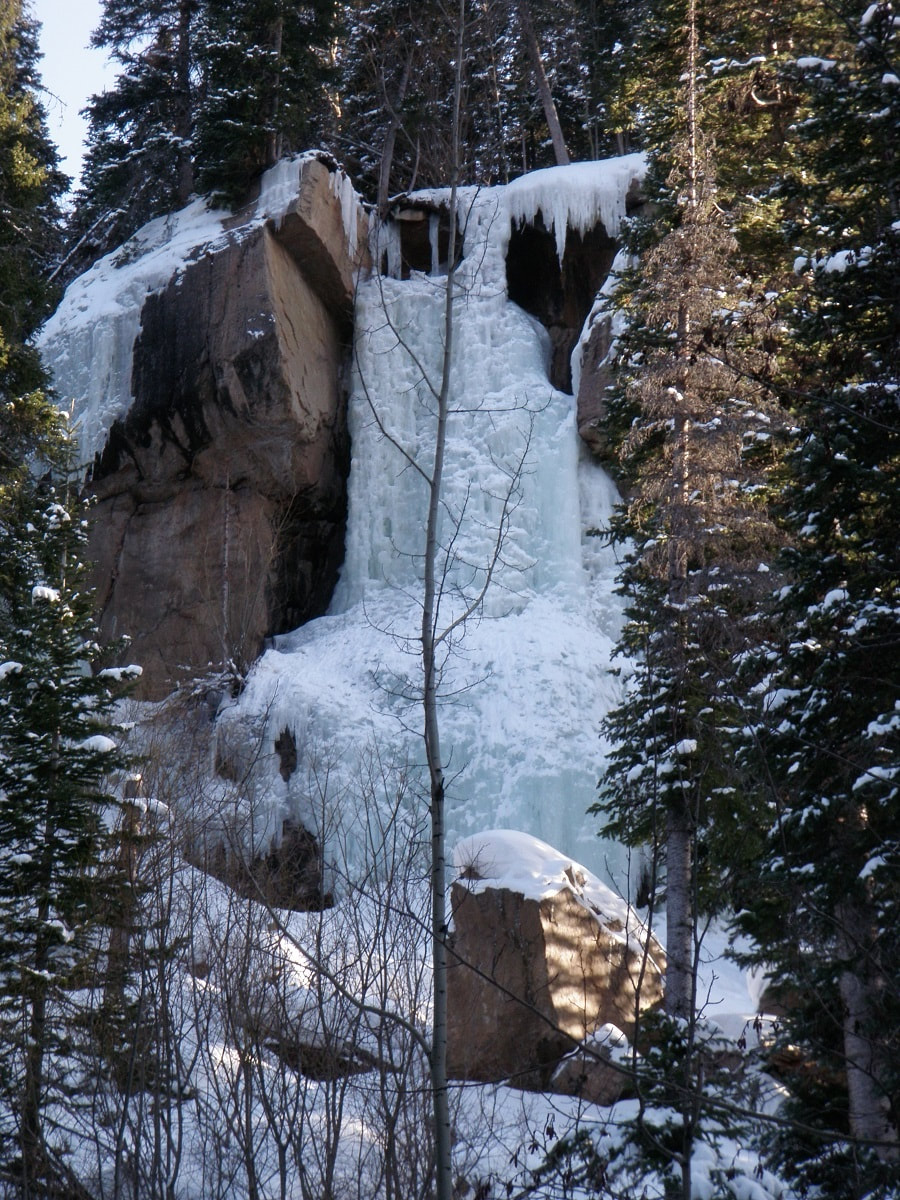

story and photos by Rebecca Detterline The golden peach light hitting the December snow on these shortest days of the year always brings me to a place of quiet contemplation. Pausing at the Saint Vain bridge 2.4 miles from the Wild Basin winter parking area, I breathe in the cold winter air and reflect on the past decade. When I moved to Allenspark in 2012, Wild Basin quickly became my sanctuary. Whether fly fishing in Ouzel Creek, tagging a remote summit or jogging up the Finch Lake trail, I always feel at home in The Basin. During the winter season, the far reaches of Wild Basin are inaccessible to most of us mortals, buried deep under an untouched blanket of snow. Skiing off the summit of Mount Copeland in January of 2017 required starting in the pre-dawn darkness and ‘over-skiing my headlamp’ on a dark, icy trail well after sunset. I almost made it to Thunder Lake on skis in early 2020, but breaking trail in deep snow, route-finding difficulties, and the impending sunset forced my partner and I to turn around just 1/2 mile shy of the lake. The Wild Basin winter parking area will sometimes fill up on busy winter weekends, but spots can usually be found in the nearby summer stock parking loop. Weekdays, however, offer much solitude. Hikers can plan to share the one-mile stretch of road between the parking area and the Wild Basin trailhead with a handful of ice climbers, cross-country skiers, and families trying out rental snowshoes. The road is usually hard packed, as is the short trail that leads to Hidden Falls. However, hikers should carry snowshoes and anticipate breaking trail for destinations along the Wild Basin Trail. In the summer months, Hidden Falls is nothing more than a trickle of water seeping out of an overhanging rock ,100 feet above the forest floor. In the winter, that trickle transforms into a spectacular frozen waterfall, very popular among ice climbers. The round trip distance for this hike is approximately 3.5 miles. From the parking area, follow the road past the Finch Lake trailhead. Just before the road takes a sharp right and crosses the North Saint Vrain Creek, look for a sign for a horse trail and follow the hard-packed trail to Copeland Falls. Continue along the trail, looking to the south for glimpses of this impressive ice column. The climbers’ trail heads up to the left and is generally easy to spot. This trail steepens and continues to the base of the falls, but quickly becomes covered in solid ice. Crampons are needed for this section of trail and hikers should enjoy the views of Hidden Falls from below this icy slope, safely out of the way of any falling ice chunks the climbers might dislodge. Ouzel Falls is a worthy destination in any month of the year, but the most solitude is found on the shortest days. But hikers need not travel 3.7 miles from the winter parking area to enjoy the quietude of Wild Basin in the wintertime. Only .3 miles from the Wild Basin trailhead, winter hikers can revel in the rare opportunity to have Copeland Falls all to themselves. Pausing at the bridge that crosses the North Saint Vrain Creek 2.4 miles into the hike, I watch the water flow between the rock slabs and ice sheets that encase them. So much literal and proverbial water has flowed under this bridge in the years since I’ve made this place my refuge. Through triumphs and heartbreaks, fires and floods, anguish and joy, the trails in Wild Basin have been an enduring comfort. The seasons of life are not so predictable as the seasons of the year, but the ever- flowing snowmelt in the creeks and waterfalls of this magical place always brings a sense of peace. Whether hiking to Hidden Falls, Copeland Falls, Calypso Cascades, Ouzel Falls or destinations beyond, the tranquil solitude of a winter visit to Wild Basin is sure to leave the hiker feeling refreshed and rejuvenated. The darkest days are behind us now and Wild Basin is an ideal spot for quiet reflection as we begin heading for light.  Rebecca Detterline is a lover all things RMNP. She is a wildflower aficionado whose favorite hiking destinations are alpine lakes and waterfalls. Her name can be found in remote summit registers in Wild Basin and beyond. Originally from Minnesota, she has lived in Allenspark since 2011. The publication of this piece was made possible by the Mad Moose, and the Country Market, both of Estes Park.

2 Comments

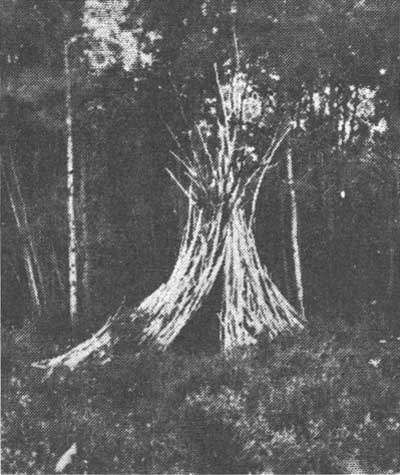

Research & story by Hillary Eichinger  Sprague family homestead in Moraine Park; NPS photo Sprague family homestead in Moraine Park; NPS photo Winter in the Rocky Mountains is harsh, often bringing sub- zero temperatures, frequent storms and high winds. Elk, deer and moose will move down to lower elevations during storms and freezing winds. So why then did early people continue to come back or choose to stay? The easy answer is the abundance of resources and vast sweeping landscapes. Fresh water, abundant wildlife and many wild edible plants attracted people to the dense terrain and high peaks. The Rockies, although severe during winter, provided enough food during the summer and fall to sustain human life. There have been people in the Rocky Mountains and surrounding foothills for more than two thousand years. The Ute Nation believed the creator god Sinawav (Sinauf) specifically placed them in the Rocky Mountains and at Mesa Verde as the chosen people while distributing the other groups of people around the globe. They were to be stewards of the land forming a close relationship to the seasons and changes of the area. The Ute people are not considered nomadic because they returned to the same places, year after year, depending on the season. The area from Denver and Cortez to the east, most of Rocky Mountain National Park and west to Northern Utah, and south to what today is Northern New Mexico were part of their territory. They defended the area fiercely but did not inherently seek battles with other indigenous people that would sometimes include the Arapaho, Cheyenne, Shoshone, and Navajo nations. They traded with Pueblo peoples in New Mexico for pottery to be used in food storage for winter.  “Chief Ouray, pictured here with his wife Chipeta, was one of the most influential leaders of the Northern Ute people in the late nineteenth century. A known intellectual and skilled diplomat, Ouray negotiated treaties and attempted to avoid conflict with whites wherever possible.” (coloradoencyclopedia.org) During the spring and summer months. the Northern Ute bands would break up into family units to return to certain wild crops and hunting grounds. They remembered specific berry bushes, seeded meadows, good places for fishing, and small game hunting areas to return to every year. They also planted seasonal crops like corn, western potato and squashes. The small family groups were careful not to overtax the land, making sure to not take an entire crop or overuse the soil. By leaving some food behind for Mother Nature to recover or for animals to eat, they cultivated the edible resources they would return to. The Northern Utes believed that they were owned by the land, rather than the other way around. They gathered wild mountain foods including chokecherries, wild raspberries, seeds from grasses and trees, pinenuts, and dried crickets. The yucca plant was very important as it was used for basket making, tea, pulp cakes and medicine. The inner bark of the ponderosa pine was harvested for its medicinal properties. It could be used as a compress, to fight infections and as a healing tea. The men would fish and hunt large game such as deer and elk while the women trapped small game like rabbits and ground squirrels and gathered wild berries and seeds. Bison were not hunted in abundance by the Ute Nation until after 1600, when they acquired horses from the Spanish.  Wikiup/NPS photo Wikiup/NPS photo During the late fall when the weather would start to turn cold, they would travel out of the mountains and meet up with other families. The large number of people allowed more protection from hungry predators and attacks from other tribes looking to get quick resources in the winter. The entirety of the band would gather together for the winter months in a few carefully chosen locations. The Northern Ute bands would camp along the White, Green, and Colorado Rivers in what is now known as Utah. This was a time of rejuvenation, food sharing and crafting. Elders would tell stories, pass on traditions, and arranging marriages. Women would make clothing, spending hours on intricate beading patterns that became famous and highly sought after among other tribes. Clothing and moccasins were typically made from animal hides, most often deer and rabbit. Families would stay together for the deep winter until the bear ceremony in the spring, which marked the time when the hibernating bears would wake up and Mother Nature was ready to start a new cycle. The deep winter months in the Rocky Mountains remained empty of humans until the early homesteaders and pioneers built homes on top of the Ute summer sites. The Spanish saw the land of the Utes was full of resources that they valued such as wild game, timber, and fresh water. Because of the harsh weather conditions, rough terrain, and Ute occupation, white settlers did not arrive until 1860 when Joel Estes stumbled on the valley while hunting for a gold deposit. He “claimed” the land by squatting and building two cabins that he and his family used year round. Later he brought up a herd of cattle that had to be watched and guarded constantly from indigenous hunting groups and predators. The ground froze solid in the upper elevations and the cattle had to be brought in close to the cabins to protect them from winter storms and mountain lions. Estes made a small fortune by selling wild game meat in the winter months. He would haul as much meat as he could down the mountain and sell it to the hungry miners prospecting at the base of the mountains in Denver and Golden. Most of the farming work was accomplished in the short summer months and the fall. Hay had to be grown in abundance and stored to last the cattle through the winter. The Estes family relied on stored food, dried meat, and salted fish. The demand was so high for meat that a writing by Milton Estes, Joel's son, reported that he personally shot and killed one hundred elk during a summer and fall season to sell. The trip down to Denver would take four days and then another four back laden with provisions. By the winter of 1864-1865 the weather and living conditions were so severe that the Estes family decided to leave. That winter, Milton Estes described how the snow started in late November and did not thaw until spring. They had to dig through two feet of snow to reach grass to feed the cattle. That year they had to move the cattle down the mountain to save the herd from starvation. Joel sold his claim for a yolk of oxen to a man named Buck in 1866 and in April, the family left, never to return. They settled in southern Colorado and established a ranch where the weather was milder and there was more room for the cattle. News of the Estes family’s valley and beautiful mountain meadows reached other homesteaders and ranchers. Using the trails established by the Ute and other indigenous people, pioneers started ranches, homesteads, farms and timber camps. Once silver and important minerals were found in the Rockies, more mining camps and quarries were established. Lord Dunraven was the first to enthusiastically enter what was now named Estes Park to hunt and attempt to own land for recreation. Winter enthusiasts and mountaineers streamed to the area to enjoy what was described by Lord Dunraven as “long spells of good winter weather interrupted by frequent storms.” Despite the frigid temperatures, intense storms and harsh terrain, pioneers and homesteaders made time for the holidays. Abner Sprague, later to be a land owner himself in what is today Moraine Park, spent two days hiking high into the mountains with a friend to obtain a Christmas tree. The tree was brought back to the community hall in a wagon filled with hay. They put presents that had been obtained in Denver and stashed for months around the tree for Christmas. In Grand Lake in 1883 the Fairview House hosted a New Year’s Eve party. Everyone in the community was invited and a horse-drawn sleigh was sent out to gather anyone who couldn't otherwise make the trek. They enjoyed a large dinner that started at 10 pm and ended with a toast at midnight. Dancing was a popular holiday pastime that people looked forward to it all year. That night they danced until dawn when it was safe to travel again. “The party opened and closed with all joining hands and dancing around the central Christmas tree.” (Grand Lake in the Olden Days, pg 169) Today there are nearly six thousand year-round residents that enjoy winter in Estes Park. Visitors come to Rocky in the winter to snowshoe, hike, and backcountry ski - some of the same activities the pioneers and early native people did. To find out more about native Colorado people and early pioneers, consult these excellent resources: Estes Park a Quick History, Kenneth Jessen, 1996 The Utes, the Mountain People, Jan Pettit, 1990 My pioneer Life, Abner E Sprague, 1999 Early Estes Park Narratives, Milton Estes, 2005 Grand Lake in the Olden Days, Mary Lions Cairns, 1971 https://www.southernute-nsn.gov/history/ute-creation- story/ https://utahindians.org/archives/ute/earlyPeoples.html  Hillary Eichinger was born and raised in Oregon. She received a bachelor's degree in history and a master's degree in museum studies. she has worked with artists in gallery and museum projects for over 20 years. She is passionate about art, history, photography and natural preservation. This piece of independent and local journalism was made possible by Snowy Peaks Winery and MacDonald Bookshop/Inkwell & Brew.

Memoir and photos by Chris Revely Author's NoteMy next few contributions to HIKE ROCKY are based on recollections of four years of employment with the National Park Service (1978 – '81), served mostly around Longs Peak. These memories are vivid. But are they completely true? In the late 1970s, rumors of high winds around Estes Park had reached the East Coast. Meteorologists working on Mount Washington in New Hampshire, where a long-standing world-record wind speed of 234 mph was measured, wondered if that record might be broken along the Continental Divide in Rocky Mountain National Park. As a Longs Peak backcountry ranger, I was recruited to assist with the construction of a wind measuring device on the summit of Longs Peak. Later, the project would require more extensive, personal involvement. In the Fall of 1980 (or was it '81? See authors note) personnel and equipment were assembled at an often-used staging area along the upper Beaver Meadows road. The helicopter arrived and over two days, we made several flights loaded with tools and materials to the summit of Longs Peak . Having proudly struggled to the summit of Longs scores of times under my own power, the experience of rising, effortlessly, in one unbroken line of ascent from the take-off point to the top was both exhilarating and eerily disturbing. My thoughts toggled back and forth between, “WOW!!! What an amazing machine” and “There is just something wrong about getting to the top of Longs like this.” On the flat summit about 100 yards northwest of the often-visited high point, a solid metal mast with its spinning anemometer attached, was secured in a vertical position with several heavy-gauge steel wires tightly anchored to large rocks. Thin transmission wires wound down the post and reached the recording apparatus near the base. We were assured by the Mount Washington team that this arrangement could withstand anything the atmosphere might dish out. As a resident Park Ranger at the Longs Peak trailhead that year, I was unanimously elected (at a meeting I don't recall attending) to service the wind measuring apparatus throughout the winter. It was a project I naively and enthusiastically embraced due in part to the competitive verve that had sprung up around the project. Could Longs Peak beat Mount Washington? Data from the anemometer would be recorded by a stylus on paper if - and only if - the tension spring that turned the paper's cylinder was wound up regularly, like winding an old-fashion grandfather clock. The winding, I was told, should take place once weekly (?!!). The magnitude of the project and my responsibility became disturbingly clear: it would entail frequent trips to the mountain's summit from the Longs Peak trailhead, throughout the winter. Success would depend on regular, reasonable climbing conditions on twenty separate days, from November through March. (Hmmmm….. lots of unspoken ifs in that plan). The winding of the apparatus was achieved with a metal wrench. I would have to remove my heavy, outer mittens and execute the essential maneuver wearing little or nothing on my hands while being slapped around by icy gusts on the exposed plateau. I knew that conditions around the summit would sometimes be so extreme as to preclude reaching the contraption, much less performing the necessary activities out in the open. A plywood coffin-like structure was designed, built and snuggly fitted up against the recorder. Entry to the long narrow box was made through the opposite end, which was fitted with a hinged door. This seemed to solve the problems of access and protection. Once weekly, I left the trailhead with plenty of clothing, food and water. I carried two ice-climbing tools, crampons, a light rope and a few pieces of gear to a place of protection in case conditions on my preferred approach (the North Face) required self-belay. Once past the technical difficulties of the old Cables route, the remainder of the climb involved only kicking steps in snow and finding my way over and around large boulders to the edge of the summit plateau. From there, the last leg of the approach resembled trench warfare. At just the right moment, having waited for a break between volleys of wind, I would break into the open, fully exposed to fire from the enemy, and proceed, crab-like, zigzagging on hands and feet to the coffin, my only point of cover. Once inside, I could relax and take care of business. That winter, between November and late February, I reached the summit (of Longs) on fewer than half of my attempts. My journey to the top always started with the best intentions but often ended in a hail of flying gravel and battering wind below the Chasm View overlook. While the recorder waited patiently for its recharge, I wound it up, more often than not, laying on my side, curled on the floor of a body-size crack below the North Face, laughing at the absurdity of my pitiful situation. At those moments, the decision was easy; if I can't go on safely, it’s time to go down. Turn around at any point on that route and it is all downhill and down-wind to the trailhead. The irony of my situation was, however, harder to escape: There I lay, defeated by extreme wind, the very phenomenon we were most hoping to record. Throughout the winter, I the reached the site when I could and information continued to be collected. Sometime in late February, the steel mast came down and wires were scattered across the summit by (of course) high wind. On New Hampshire's Mount Washington, weather data is collected throughout the year from instruments mounted atop bunker-like, reinforced buildings. Weather station employees travel to the 6,288-foot summit in heated snowcats, spending several days in residence reading instrument gauges while sipping coffee in heated work areas. By comparison, our approach to the hunt for high wind on the 14,256-foot summit of Longs Peak was laughably inadequate; poorly conceived, badly executed and doomed to failure from the beginning. Longs Peak did not officially win the wind speed contest. But I'm not entirely sure it lost. We will never know exactly how much faster the wind blew after the equipment was flattened. Is it worth another try? Today, with improved technology, more sophisticated equipment and a better understanding of wind dynamics around surface features, the odds of success would certainly improve. I suspect there may still be world-record wind waiting to be found among the high peaks of Rocky Mountain National Park. Read a brief synopsis of the wind research project on Rocky Mountain National Park’s website; and, DE Glidden’s report on this project, which was funded by the Rocky Mountain Conservancy is also available online.  Chris Reveley has spent 50 years climbing and doing endurance sports; and, thirty years learning and practicing medicine. “Now I’m a Happy House Husband with hobbies,” he said. The publication of this story was made possible by Images of RMNP and Brownfields.

|

Categories

All

|

© Copyright 2025 Barefoot Publications, All Rights Reserved