|

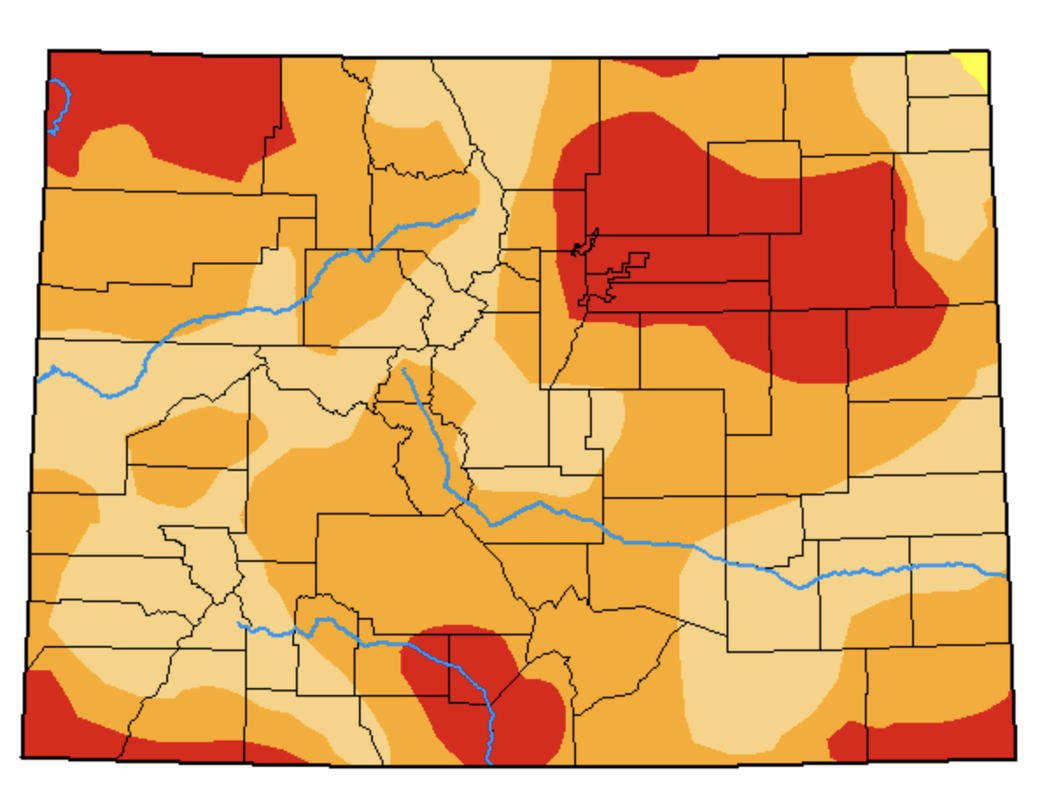

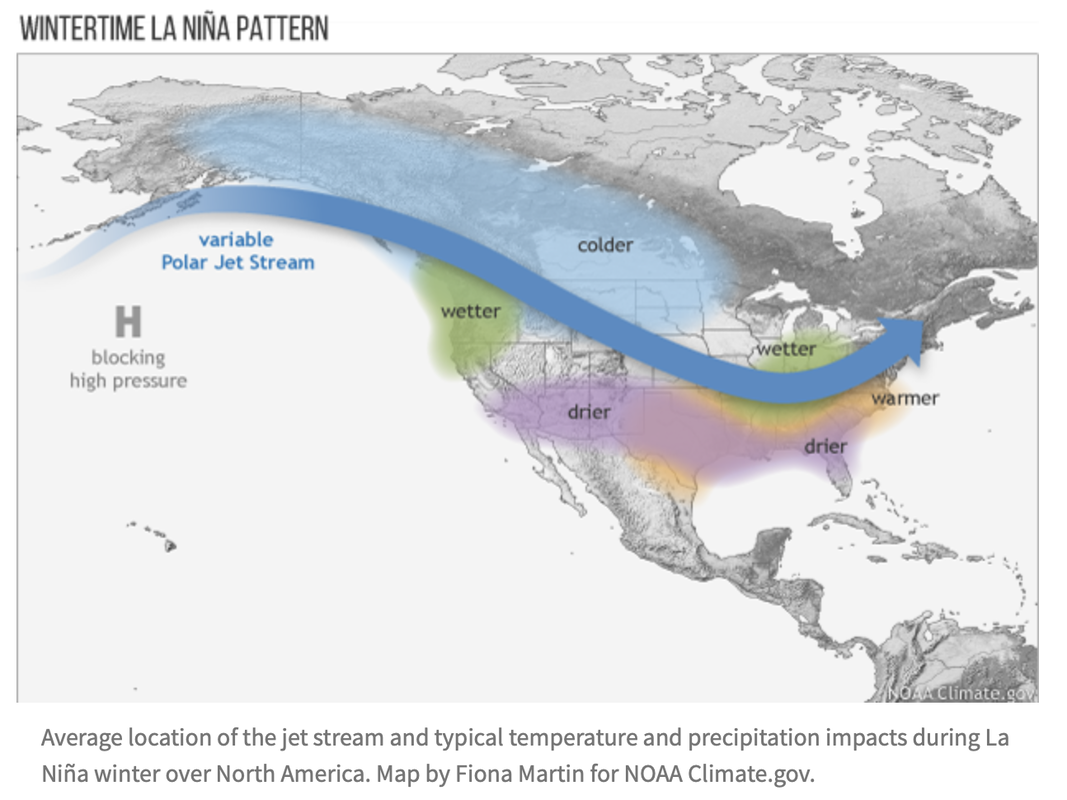

Story, photos & video by Dave Rusk The Bear Lake trailhead is, without a doubt, the most popular trailhead in Rocky Mountain National Park. I think it's fantastic that there's a mountain lake so accessible to a great many people who otherwise might never get to see such majestic beauty. For many others, going a farther 1.1 miles to Dream Lake is challenge enough but with an unmatched mountain experience. It's always astonishing to me that this trail isn't more beat up and worn out given the thousands of hikers that trek to see the Dream each year. Tucked off from this well-visited trail is the Lake Haiyaha trail. Even though it's only 2.2 miles from the Bear Lake parking lot, the lake is often overlooked by the many Dream Lake trekkers. In fact, because the Bear Lake parking lot is so full of Bear Lake and Dream Lake hikers, this lake is often less visited than it might be. It is a lake with a pronunciation that even laughs at itself (just remember when trying to spell it, the “a” goes before the “i"). They say the name means “rock” and indeed there are boulders strewn about everywhere in Chaos Canyon that stretches above the lake. In early November, I hiked to up to Lake Haiyaha to see how the snow conditions were faring (see the video). Starting the hike at 9,475 ft., the trail rises up 745 ft. to an elevation of about 10,220 ft. While Rocky had experienced some October snow storms, most of the trail conditions at that time were icy with very little snow coverage, until I got above 10,000 ft. When I was there, the lake was mostly frozen over, but not solid enough for ice skating just yet. When I reached the lake, the wind was blowing hard down Chaos Canyon.  I returned to the lake again in mid-December and found the conditions had become much more winter-like with more snow and cooler temperatures. Some early December snows brought increased snow coverage down to below 9,000 ft. covering over any icy spots on the trails. While snow travel even at 10,000 ft. did not yet necessitate snowshoes, a decent snowpack was beginning to set up. The wintery conditions I found in mid-December had not been aided by our November weather pattern. In fact, according to the November Climate Summary Report from the Colorado Climate Center, this year's November was the third warmest for the state and ranked as the 11th driest on record. In short, our November was warm and dry, increasing drought conditions in our region to moderate and running the snowpack for the early season to below average. Colorado state climatologist Russ Schumacher is blaming a La Niňa ocean pattern in the Pacific that typically shifts moisture farther north. Whether any of that moisture will drop down in latitude on our mountains will largely depend on where the Jet Stream sets up. NOAA forecasters are “confident” that the La Ni~na pattern will persist through the winter. However, Schumacher did add, “It's still very early and a lot can change between now and the spring,” hedging his bets, like any good weather forecaster would. I hope change comes. But winter had set in up high and the six or so inches of snow on the Lake Haiyaha trail was getting packed in. In the summer, this trail is a pretty nice moderate hike with good views of Longs Peak and the Glacier Gorge region along the way. But in the winter, it can be a different game. While the winter trail to Dream Lake sees lots of travel and is usually well established, the number of snow travelers drops off considerably for the Lake Haiyaha trail cutoff. A good snow storm can quickly cover over the existing snow-packed trail and it could be easy for whoever is breaking the new trail at the time to get off course, leading followers astray. What seems like a relatively nice winter venture could get tricky real quickly if someone not familiar with the surrounding terrain were to accidentally drop down into the Chaos Canyon area under less than favorable weather conditions. On the day I went, the fresh snow was good and there was a decent path that stuck to the trail. Though the temperature was cool, I had to continually pull my cap off to keep my head from over heating and getting too sweaty. It can be easy to overheat when hiking in winter conditions and then become quickly chilled in the wind when stopping for a rest. There were several small groups that were making their way to the lake while I was out. One gentleman had even brought ice skates! Once I got to the lake, I found the wind was still blowing hard down canyon.  Dave Rusk has been sauntering and taking photographs through Rocky Mountain National Park for decades. He is the author publisher of Rocky Mountain Day Hikes, a book of 24 hikes in Rocky, and the website of the same name. He is the publisher of HIKE ROCKY Magazine and an important content contributor to all of these endeavors.

0 Comments

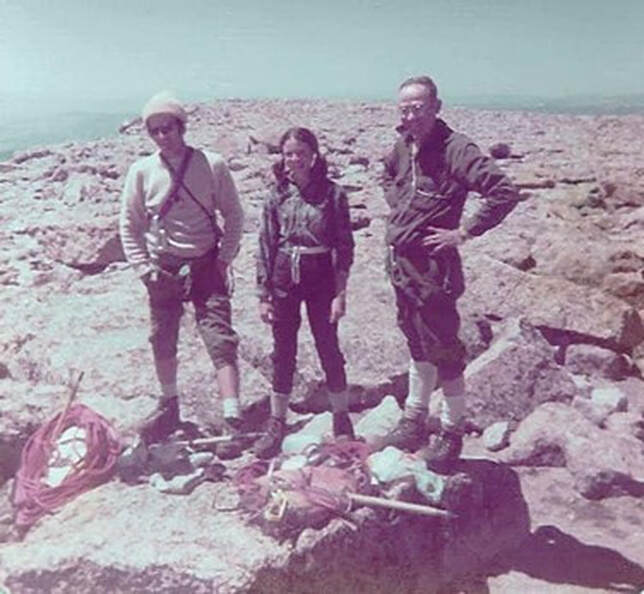

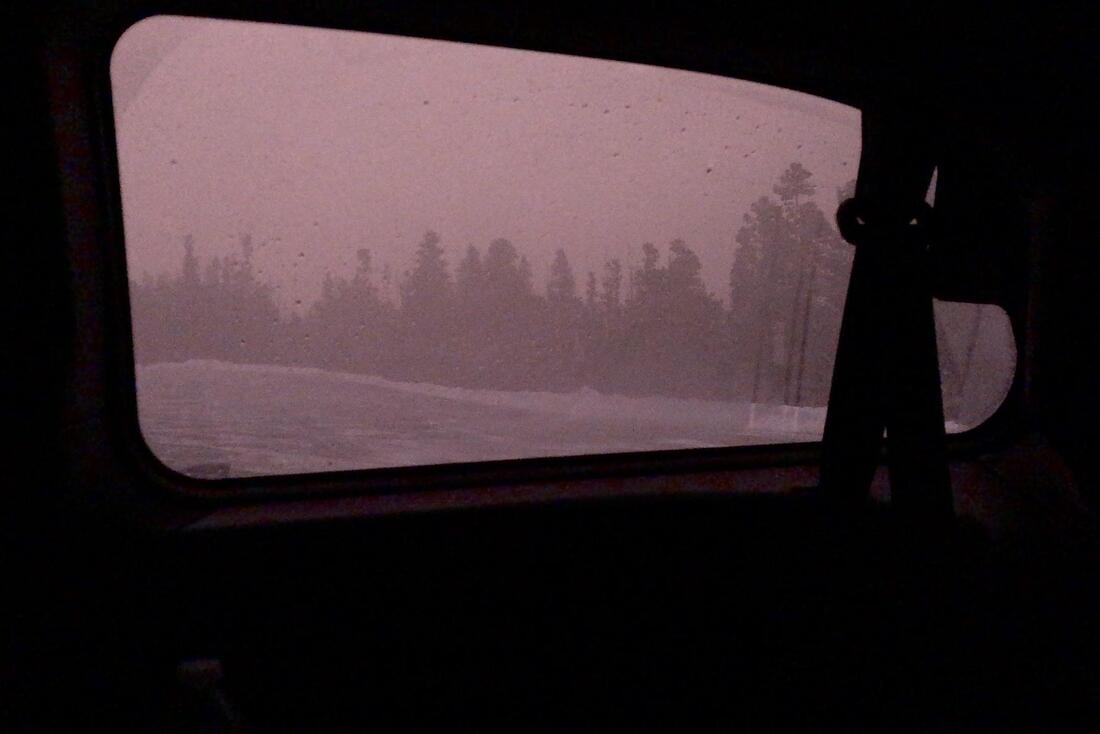

Story and photos by Marlene Borneman It began innocently enough, in 1974. l came to Colorado for a summer job at the YMCA of the Rockies in Estes Park. I arrived from New Orleans (yes, below sea level) in mid-May of that year and, being a proper young lady from the South, l wanted to make a good impression on my new employer. l wore a sleeveless silk dress (rather short as I recall), stockings, and the cutest little heeled sandals you ever laid eyes on. It was somewhere around 30 degrees and spitting snow. It turned out to be one of the scariest days of my young life. All l could think was, "l have made a terrible mistake!” Fortunately, those feelings didn't last all too long. Once over the cultural shock of my summer home, I seeded into the rhythm of working and learning about a phenomenon called "hiking." I was fortunate to meet Dick Chuttke. He was a retired gentleman, a YMCA member, and a Colorado Mountain Club member who enjoyed hiking with the YMCA groups. Ironically, he suffered from acrophobia, an irrational fear of heights. He became my climbing mentor for the next 20 years; he taught me how to be fast and careful at the same time and instilled in me the ethics of Leave No Trace before it was popular or common. From short silk dress to summits, my progression came fast. By the end of that summer, I had climbed most of the major peaks in Rocky Mountain National Park. Having graduated from college, l decided to stay in Colorado. You might say the rest is history, but it was not that simple. I lived in Estes Park for 12 years and climbed in the park year-round. I found myself focused on the major peaks, and their different routes, with a few new peaks thrown in now and again. Then came a career move away from Colorado; to say I began grieving would be an understatement. But, by 2001, I had returned to live full time in Estes Park. After completing 54 fourteeners in 2005, I was hit with the pain of guilt. I imagine you all know what it's like to ignore a friendship. This was worse: it was like neglecting your own husband. After all, Rocky Mountain National Park was now in my backyard. I began to rekindle my relationship with Rocky, and started studying the map with new interest and curiosity. When you get down to it, though 35 years had passed Dick's spirit motivated me to complete the 126 named summits in Colorado's crown jewel. This was the project I needed to turn neglect into passion. First, I carefully laid out the list. There were 35 peaks in Rocky I hadn't yet climbed. By the summer of 2009, I had only three to go. Then reality struck me hard. The final three were The Sharkstooth, Hayden Spire (both Class 5, technical climbs requiring ropes and equipment) and Pilot Mountain (a difficult, though less technical, Class 4 climb). Had I set myself up for this? Shouldn't the last peaks be easy, like Estes Cone or Twin Sisters? I hadn't climbed anything beyond Class 4 in years. I lost some sleep, talked incessantly to my husband, and consulted every book and person whom I thought could set my mind at ease. Then I came to the realization that the final three were meant to be my grand finale. I needed a challenge; I wanted a challenge. I needed to gain my confidence back on the rope; I needed a plan. It felt like I needed a lot. The Sharkstooth was the first of my final three and, as it turned out, my most challenging climb in Rocky. My climbing partner and I left the parking lot at 3:45 a.m. I once read that eighty percent of success is just showing up. I liked my chances. The sky turned cloudless: a deep blue, Colorado morning without a breath of wind. We would be climbing the East Gulley Route (5.4). The first pitch was going easy enough on ledges, until we came to a short, but very exposed traverse. I watched my partner go across with ease up to a small crack, out onto a smooth rock face, then scramble up another crack. Traversing the ledge looked feasible but when I came to the first crack, I just couldn't visualize the move. I stared at it for what seemed like an eternity. Here I was, committed to this menacing climb, and the first move was proving to be baffling. The staring must have helped. Finally, it all came together and it was over, behind me. I was sweating like a pig. Good thing I had given up that silk dress. Things were going smooth until the crux: a wall of 60 feet, extremely exposed. Once again, I was paralyzed. I found myself looking at this wall, caught in my own world for endless amounts of time. I had watched my partner climb straight up with ease. Finally, I took a deep breath and let it out slowly. I knew I needed to move quickly; no hesitating, just go. I stepped out onto the wall and got my fingers into the crack, trusting my climbing shoes to hold onto what seemed to be nothing and scampered up. Though my stares felt eternal, my moves seemed mere flashes; I was on top of the cliff. As I climbed toward the summit, tears were in my eyes. This was what it was about: I hadn't gotten here because of a list, but because I had taken a risk. Ultimately, I reached the summits of the final three with a smile from ear-to-ear. I found myself enjoying these peaks more than I imagined. I will forever remember the air beneath my feet, the sudden flight and song of finches above my head, the simultaneous sense of inner relaxation and burst of excitement, and the incredible sound of the silence around me.  Rappelling down Hayden Spire in 2009. Rappelling down Hayden Spire in 2009. You may ask, is there anything left of that southern girl from 1974? My father was a riverboat captain, checking catfish lines across the river while trolling for shrimp in Lake Pontchartrain at 5 a.m.; he lived with patience, endurance and perseverance. I gained these traits from him. Maybe this is why I adapted so well to the mountains and persevered to the top of 126 of Rocky's best.  Marlene has been photographing Colorado's wildflowers while on her hiking and climbing adventures since 1979. Marlene has climbed Colorado's 54 14ers and the 126 USGS named peaks in Rocky. She is the author of Rocky Mountain Wildflowers 2nd Ed, The Best Front Range Wildflower Hikes, and Rocky Mountain Alpine Flowers. Story, photos, and video by Murray Selleck, HIKE ROCKY Equipment Specialist. Please note: these reviews are not solicited, and we received no financial compensation for these reviews. Snowshoeing is a wonderful winter extension of your love for hiking in the summer. All your favorite summer trails in Rocky Mountain National Park become easily accessible winter trails with a pair of snowshoes. Snowshoeing offers a completely different yet intimate wintery mountain experience. The soothing yet smothering quiet of a snow-filled forest when you compare it to the noise of our frenzy paced towns and cities is comforting. Watch out when the wind releases snow-loaded pine branches of their wintery burden. Count yourself lucky if one of these big clumps of snow doesn't target you from above. The resulting whomp whomp whomp of these big clumps of snow hitting the snowpack will have you hunching up your shoulders just in case! The sound of your snowshoes compressing soft powdery snow underfoot along with the cheering chirps of mountain chickadees will only make you want to snowshoe farther and deeper into the forest. Yes, snowshoeing really is quiet, wonderful, and peaceful. A challenge all snowshoers face isn't the activity of snowshoeing itself. Everyone can enjoy snowshoeing, from youngsters to oldsters alike. No, the challenge is deciding which pair of snowshoes is right for you. A quick count of companies producing snowshoes these days is up around 24. Back in the mid 80's when snowshoeing saw a huge resurgence, Redfeather Snowshoes was practically the one and only choice. Snowshoe deck sizes, snowshoe talons, crampons and cleats for traction, frame designs, bindings. All these features will come into play while you’re making your decision. Here are some initial tips for you to consider when making your purchase. Pretty much all snowshoe manufacturers publish a weight range for each size snowshoe they make. This is helpful but typically the weight range is so broad it includes all of us anyway. When I help folks choose a snowshoe I ask them to consider where they are likely to snowshoe most often. Will you be snowshoeing on a packed trail or do you like to explore, go your own way, and break a fresh trail in deep snow most often? Will the terrain you like to snowshoe on be more golf-course like or mountainous with lots of climbing and descending? The answers to these questions will help determine snowshoe deck size and how aggressive the traction crampons or talons underneath the deck should be. For packed trails and tamer terrain, you can choose a smaller frame for an easy lightweight and more maneuverable snowshoe. For more adventurous terrain and breaking trail in deeper snow you'll benefit from a larger snowshoe for more floatation with more aggressive traction talons underneath. A retractable climbing bar is a great performance benefit. And what if you think you will be snowshoeing a bit in each situation? The middle ground is a good compromise as long as you're aware of the pros and cons of your choice. On packed trails a larger snowshoe can feel a little clunky. A smaller snowshoe in deep snow will make breaking trail tougher (but not impossible). Both will work in either snow condition but it is the awareness of how your snowshoe will perform in each condition that allows you to make those compromises. Women's specific snowshoes typically have all the same features of a guy's snowshoe but the frame is narrower. A narrow snowshoe helps women stride more naturally avoiding the infamous “clam diggers” walk as if walking through tidal mud flats. I like to snowshoe with poles. Even on mild terrain a pair of poles lets my arms and hands, shoulders and torso become involved in the activity. Poles help you climb more efficiently and they provide additional stability on steep descents. Of course, budget will determine your comfort level with a snowshoe purchase. And as usual, you get what you pay for applies to snowshoes, too. The more dollars you are able to put towards your snowshoe purchase you will be rewarded with long term durability and no- fuss binding reliability. The last tip is to try the snowshoe binding in the store. Bring the boots you are likely to wear while snowshoeing so you can try them on. Go ahead and strap on the binding to determine ease of use and retention. There really is no good reason to have to readjust your bindings while snowshoeing. The only time you should adjust the binding is putting them on or taking them off, not while you're on the trail. Here are three snowshoe manufacturers that I really like and have had good experiences with. TSL Snowshoes TSL is a French company and their snowshoes are manufactured in France. If anyone has really made some nice snowshoe design strides over the last few years it is TSL. Their Symbioz models feature HyperFlex. The snowshoe has a wonderful round flex pattern that allows you to walk and hike with a very natural heel-to-toe stride. You feel this feature especially on packed trails and descents. The bindings have some great adjustment features. The length and width of the binding can be adjusted for boot size. The most unique aspect of the length adjustment is the climbing bar is always in the perfect position under your heel. The retention strap that comes forward over your ankle adjusts easily with a ratchet and is easy to reach. Some traditional heel straps can be low to reach and awkward to adjust. TSL does not make men's or women's specific models. They do make 3 different sizes in each model. Small, medium, and large sizes cover your snowpack and trail considerations. Their hourglass frame shape makes for an comfortable stride (along with HyperFlex). Do yourself a favor and check out all the TSL snowshoe models. Atlas Snowshoes Atlas has a complete line of snowshoes from models that are appropriate for a snow covered golf course to snowshoes that are ideal for very adventurous terrain. One terrific snowshoe model that's right in the middle of their line is the Montane. The Montane comes in men's and women's models and sizes. Women's snowshoes are narrower than a men's snowshoe. The narrow design allows women to achieve a more natural stride. One of the best features with Atlas is their spring loaded or SLS binding. Spring loaded allows the tail of the snowshoe to lift off the snowpack as you step forward, reducing tail drag. It also helps the tip of the snowshoe to lift up and over the snow as you step forward breaking trail. The Montane has an easy one-pull-loop to close and a one-pull-loop to open to open the binding with a more traditional heel strap. Easy in and easy out. Mountain Safety Research Snowshoes (MSR) The MSR Lightning Ascent is MSR's top of the line snowshoe. I really like how they attach the decking to the snowshoe frame. It is attached all within the snowshoe frame. None of the decking wraps around the exterior of the frame. Wrap-around decking can be a wear point but there is no such concern with the Lightning. The Lightning's frame is also a huge part of the snowshoes traction. Along both sides of the frame, teeth have been cut into the metal creating very secure traction. The traction frame also helps when you are traversing a side slope. This snowshoe resists slipping and sliding downhill away from you. MSR's new binding design incorporates a plastic mesh that wraps around your forefoot. Two side straps will snub your boot into place along with a traditional heel strap. Very effective and comfortable. These are just a few of the snowshoe features and highlights from three excellent snowshoe manufactures. You won't go wrong choosing a snowshoe from any of these reliable companies. Winter in Rocky Mountain National Park has so much to offer. It would be a shame not to experience it and with a pair of snowshoes you will want to go, and often.  Murray Selleck moved to Colorado in 1978. In the early 80’s he split his time working winters in a ski shop in Steamboat Springs and his summers guiding on the Arkansas River. His career in the specialty outdoor industry has continued for over 30 years. Needless to say, he has witnessed decades of change in outdoor equipment and clothing. Steamboat Springs continues to be home. Guest submission by Nevin Dubinski As someone who has spent nearly his entire life in Missouri, visiting the Rockies is a treat. As we were growing up, my parents would take us west once every year or two and each time, I would learn to love it more. But of course my view of the mountains was insular, only visiting during the summer months and omitting the harsh winters that I heard so much about. I began to dream of reaching the peaks once the snow had fallen and I could partake in even wilder adventures. After years of dreaming my opportunity finally came this December when my friend Nick and I realized our finals week was free of exams. We rushed to complete what work we did have and hit the road on Monday, Dec. 13. The only unfortunate thing about the excursion was that it wouldn't technically be winter. The plan was to spend three nights near Black Lake in the backcountry of RMNP off of Glacier Gorge trailhead. The prospect of a Park free of timed-entry permits and camping fees was enough to make me reconsider my rule of sticking to less-visited National Forests and wilderness areas. On top of the solitude, the trip would only be 11 miles round trip, a distance Nick and I figured we would handle easily. Nevertheless, we knew we only had a few days to get everything together. We vacuum-sealed our own backpacking food, waterproofed nearly everything and solicited gear donations from friends and family. We needed snowshoes, thicker pants, better trekking poles and dozens of smaller things for a cold weather experience. By the end of it, at least eight people from both Colorado and Missouri had contributed to the cause. On Tuesday we reached the wilderness office at Beaver Meadows to some surprise from the staff. The lady behind the counter inspected us like the out-of-towners we were, bright-eyed and oblivious to what was to come. We assured her that we had all the necessary equipment to be a little less than miserable on our expedition and she reluctantly filled in our permit. That night we slept at the trailhead in our minivan, excited to hit the trail as early as possible. We woke up to a calm yet uneasy scene. The sky was tinted a soft pink and the sun was nowhere to be seen. Not ten minutes later the wind storm came in. 100-mph gusts jostled the van in a way only comparable to a hurricane. Walking to the bathroom involved leaning as if the world were tilting beneath me. We later found out that this same storm blew through Kansas with such severity that they shut down sections of I-70. Knowing that setting up a tent in triple-digit gusts would prove impossible, we decided to wait until the next morning to depart. Much to my dismay, the only time we left the van was for a short walk to Alberta Falls, about .6 miles up the trail. This short hike was our first official introduction to the Rockies’ mean side. The wind spat snow at us, temperatures sat well below freezing and the sky remained ominously gray. On Thursday we finally hit the trails, loaded down and elated by the near tropical weather. The sun beat down and brought new life to our steps. A few early risers had forged a clear run for us and we moved with relative speed given our weight. Aside from Nick occasionally complaining of cold fingers, we made it the 2.5 miles to Mills Lake without a hitch. We ate lunch overlooking the vast stretch of ice but didn't hang around for too long. A late start meant the sun was already retreating behind Thatchtop Mountain to the west. The trail past Mills and Jewel Lakes was non-existent, leaving us with the tough task of wading through deep cover. Hiking across the frozen lakes saved us tremendous time, but reaching the final junction before Black Lake was slow moving and brutal. When we finally did reach it the sign said just 1.2 miles further. The canyon began to narrow dramatically after this but we made it only .3 of a mile before we called it a day. Everything past the lower lakes was a mix of up and down, leaving us exhausted after six hours of uphill progress. Our camp was together by 3:30 pm, just in time for the sun to disappear and the temperatures to drop dramatically. We spent the rest of the night in the tent recounting the day and its scenery. When I went to scoop a bit more snow for boiling I witnessed one of my favorite views. The moon shone brightly against the surrounding walls and the gorge made no noise. They rose like blue giants in the light, still visible enough to count the trees on their ledges. It was surreal for such a vast place to be so quiet. As night wore on we listened to the wind pick up and screech overhead. Thankfully we were protected in our gully a few dozen yards off the trail. Large flakes came down in force, rhythmically striking the rainfly and lulling me to sleep at an early hour. The next bit of excitement came at 1:30am when I was awoken by a firm shake. Nick whispered at a near undetectable volume that something was outside the tent. I listened intently, and in between the symphony of falling snow I heard the distinctive crunch of snow, accompanied by the sound of sniffing. Nick white- knuckled his bear spray while I gripped my knife, and before too long we heard it lumber back into the night. The next morning we were greeted with several inches of fresh snow, covering any sign of the visitor. Everything was frozen solid from my contact solution to my underwear. Nick looked at me in protest and said he was ready to leave. I said he was free to leave whenever he liked, not unlike a pirate telling his captive he was free to go for a swim. I was going to see Black Lake at least once, even if it meant hiking the last mile alone. I strapped on my snowshoes and packed light. Only a few tools and some emergency supplies made the cut. The half liter of water I brought ended up being useless as the cap froze shut in the single-digit temperatures. While I was preparing another snowshoer passed our site headed for the lake, but returned just 20 minutes later to proclaim that his toes were going cold. He warned of deep drifts and unforgiving winds about a quarter-mile short of the lake. Nevertheless he said I should give it a run given my determined look. I took off up the hill, following the path he had cut for me. It became immediately clear that our early stop the night before had been the right call. The final mile was a grueling marathon through knee-deep snow while gaining several hundred feet in elevation. It took me half an hour to reach the obstacle the man had been referring to. His tracks ended at the base of a 60 degree slope, barren of anything but two feet of powder. In my first attempt I tried a direct approach, but was turned back by the impossible grade and fresh powder. I quickly reevaluated and decided to take the longer route around its edge which angled at a mere 45 degrees. After fighting it for nearly 20 minutes I knew I was in the home stretch when I reached the top. The trees broke in the distance and McHenry's Peak began to fill my southern view. My arrival was imminent. The only trail marker left was frozen Glacier Creek, which I would soon learn was not so frozen. The final pitch was Ribbon Falls, a meandering stretch of ice just below the lake which served as a perfect beginner climb. I dumped my bag and snowshoes just before the falls and made my way up the frozen slope with my ice axe and crampons. Within minutes I was making my way through the waist-deep snow on the banks of Black Lake. There was no evidence of humans, no animal tracks, or even a plane overhead. It was just the mountains and I. Directly across the lake was the largest column of ice I had ever seen, an uninterrupted sheet that traveled the final thousand feet to Frozen Lake. Sitting there in the snow I couldn't help but wonder how I might traverse it. Unfortunately I had told Nick I would be back within the hour. I said goodbye to Black Lake, confident I was the only person to have visited it that day. As I negotiated my way back down Ribbon Falls, my foot plunged into a free flowing section of the creek that had hidden itself under a foot of snow. My foot stayed dry but the slushy mix instantly welded my crampon to my boot in a bond that proved nearly impossible to break. Aside from this misstep I made my way back down the creek without incident, exuberant that I had witnessed such a beautiful view in solitude. When I reached the tent I informed Nick that he was no longer being held against his will. He had told me that morning that he had seen everything he needed for that trip, and after my final trek I was inclined to agree. We quickly packed and made our way back down to Jewel Lake. As we rounded the switchbacks near Alberta Falls in the final mile, a full moon stood proudly over Estes Park, accented by the pink and blue gradient of a Colorado sunset. The trip was one of setbacks and learning experiences, but we still managed to persevere long enough for at least one of the three nights I had hoped for. Nick and I found joy in even the fiercest conditions and I fulfilled a lifelong dream in the process. Although Nick may have been scared off for a bit, and rightly so, I'm certain I'll be back for far greater challenges in the future. Despite my inexperience I can confidently say this: Those looking for a slice of isolation should know even the most popular trailheads can offer a unique and unmolested experience come winter.

|

Categories

All

|

© Copyright 2025 Barefoot Publications, All Rights Reserved